Podcast: How can communities implement better support programs? (46:11)

Click the link below to listen to all of the researchers answer the question “How can communities implement better support programs?” in audio format on our podcast!

Understanding Homelessness in Canada by Kristy Buccieri, James Davy, Cyndi Gilmer, and Nicole Whitmore is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

1

Homelessness is an area of study that spans across academic disciplines. This was the premise with which we began this project. “Understanding Homelessness in Canada: From the Street to the Classroom” is a dynamic resource that can be used as a textbook, online course, and/or general interest book. Early in the design process, we had the idea to set up each chapter as a field of study, and we asked ourselves what three questions a student in that field might have about homelessness. We then reached out to many leading homelessness researchers across Canada and posed a sub-set of those questions to them. We recorded the conversations, created a series of videos from each, and imbedded them throughout this book alongside contemporary Canadian research with a focus on publications from 2018 and beyond.

We have included a range of academic disciplines in this book, divided into five parts consisting of Indigenous and Canadian Studies, Mental Health and Public Health Studies, Population Studies, Social Sciences, and Health Sciences. Our intention in doing so, was to provide instructors and students with a resource that contains information and opens a space for further exploration. We do not suggest that the chapters are a definitive resource for each academic discipline, but rather that they present information that students should know related to homelessness and their field. For instance, you will not learn how to be a Social Worker from the Social Work chapter, but you will learn key points Social Workers should know about homelessness. It is our intention that instructors and students will use this resource as a starting point and adapt it with their own theoretical and practical applications.

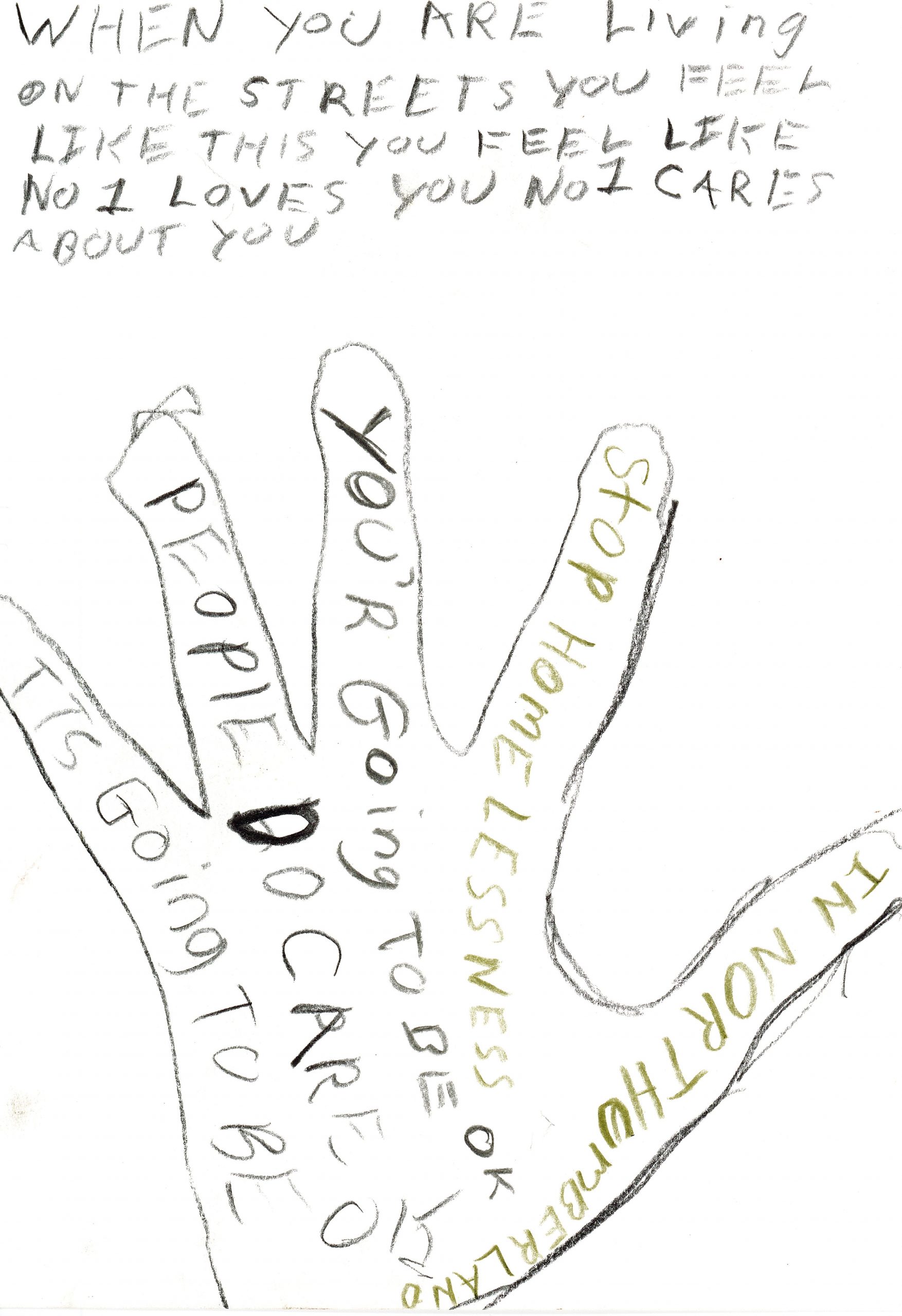

Each chapter begins with a real life scenario depicting one or more composite individuals. We have taken aspects of real people’s experiences and put them together in a way that highlights key social issues, without identifying any particular person. Throughout this book, you will also notice artwork created by people with lived experience of homelessness, additional information for students who want to learn more, and research ideas for students who wish to undertake an undergraduate or master’s thesis related to homelessness. Our team is very proud of this resource and hope that you will find it useful in your own journeys, learning and teaching about homelessness in Canada.

If you are an instructor who wishes to use the complete book, parts, or individual chapters you may wish to use the direct links below and imbed them directly into your learning management system (such as Blackboard, Moodle, or Canvas), so that students are able to easily locate the material.

Throughout this book, we consistently use a series of icons to identify key parts of each chapter. Below is an overview of what they mean and why you should be on the lookout for them.

When the videos in this ebook are almost done playing, the message “Stop the video now” will appear in the top left corner. This is a reminder for those who have the Autoplay setting turned on to manually pause the video when the speakers are done to avoid having it autoplay through to the next video. This message will appear in all researcher videos throughout the ebook.

When the videos in this ebook are almost done playing, the message “Stop the video now” will appear in the top left corner. This is a reminder for those who have the Autoplay setting turned on to manually pause the video when the speakers are done to avoid having it autoplay through to the next video. This message will appear in all researcher videos throughout the ebook.

Each chapter is designed to answer three questions that students in the field of study might have about homelessness. This icon is used to indicate a “Featured Reading” related to each of the three questions. Each Featured Reading is Canadian, open-access, recently published, and accessible through a direct link next to the icon. For instructors using this ebook as an online course, we recommend assigning these Featured Readings as required reading.

about homelessness. This icon is used to indicate a “Featured Reading” related to each of the three questions. Each Featured Reading is Canadian, open-access, recently published, and accessible through a direct link next to the icon. For instructors using this ebook as an online course, we recommend assigning these Featured Readings as required reading.

At various points throughout the ebook we use this icon to draw your attention to online resources. These additional resources are points of interest, such as websites and blogs. These are designed to take you directly to the online resource by clicking the link. Please note, they will open in a separate window, so you do not lose your place in the ebook.

Throughout each chapter, we pose questions for students to stop and consider under the heading, “What do  you think?” This icon appears next to these questions to encourage students to temporarily pause and reflect upon the material they are reading and how they feel about it. Instructors may wish to use these as discussion questions, either in class or as part of an online discussion board.

you think?” This icon appears next to these questions to encourage students to temporarily pause and reflect upon the material they are reading and how they feel about it. Instructors may wish to use these as discussion questions, either in class or as part of an online discussion board.

At the end of each section, you will encounter this icon that provides a link to the “Understanding Homelessness in Canada” podcast. The researcher videos contained within the section have been compiled into a podcast episode, for readers who wish to download and listen to them again.

To navigate the chapters, you may use the “Contents” drop-down menu on the left-hand side by clicking on the “+” sign next to the main chapter title. Once you are in a chapter, you may also move through the sections by using the “Previous” and “Next” arrows at the bottom of the page (as shown in the image below). Each page will also have an up arrow at the bottom-middle to take you back to the top.

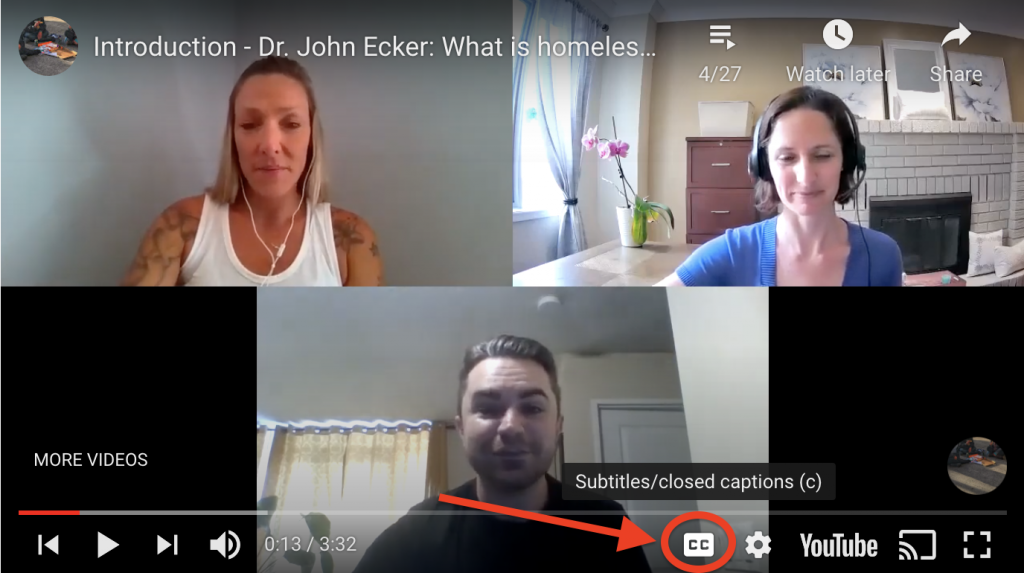

All of the videos in this ebook are fully captioned. However, depending on your own personal YouTube settings, you may need to turn them on if you want to view them. To turn on closed-captioning, click on the CC button at the bottom of the video player on the video you are watching.

We appreciate your interest in this resource, and hope that you will find it both engaging and informative. After you have read it, we hope that you will provide us with feedback: Share your thoughts with us

Happy Reading,

From the Understanding Homelessness in Canada Team

2

This is an accessibility statement from Understanding Homelessness in Canada: From the Street to the Classroom. It was generated using an online tool from Generate an Accessibility Statement | Web Accessibility Initiative. It is our intention to make this resource as accessible as possible.

Understanding Homelessness in Canada: From the Street to the Classroom takes the following measures to ensure accessibility of the ebook:

We welcome your feedback on the accessibility of the ebook. Please let us know if you encounter accessibility barriers on the ebook:

We try to respond to feedback within 2 business days for electronic communications and 2 weeks for mail communications.

Despite our best efforts to ensure accessibility of the ebook , there may be some limitations. Below is a description of known limitations, and potential solutions. Please contact us if you observe an issue not listed below.

Known limitations for the ebook:

Understanding Homelessness in Canada: From the Street to the Classroom assessed the accessibility of the ebook by the following approaches:

If you have suggestions on how to make this ebook more accessible, please contact us at understandinghomelessness.ebook@gmail.com

This statement was created on 22 February 2022 using the W3C Accessibility Statement Generator Tool.

3

We respectfully acknowledge that we, as authors of this e-book, are on the traditional territory of the Mississauga (Michi Saagiig) Anishnaabe, which is made up of Curve Lake First Nation, Alderville First Nation, Hiawatha First Nation, and the Mississaugas of Scugog Island First Nation. We offer our gratitude to the First Nations for their care for, and teachings about, our earth and our relations. May we honour those teachings.

We additionally respectfully acknowledge that people who participated in recorded interviews for this project, as well as readers of this book, may be located on other traditional lands. We encourage all people to learn about the territories they occupy and the cultures of the land’s original stewards.

The Native-Land.ca website provides a resource for beginning this engagement.

4

“Understanding Homelessness in Canada: From the Street to the Classroom” was a collaborative effort between Trent University and the Canadian Observatory on Homelessness.

Thank you to Green Wood Coalition and Peterborough AIDS Resource Network for supporting staff involvement and facilitating artwork contributions for this project.

This project was made possible with funding by the Government of Ontario and through eCampusOntario’s support of the Virtual Learning Strategy.

To learn more about the Virtual Learning Strategy visit: https://vls.ecampusontario.ca.

Our team would like to thank Emma Armstrong, Katelyn Bell, Phyllis Owusu-Ansah, Kaylie Smith, and Virginia Stammers for being student reviewers. We appreciate the time and energy you dedicated to reviewing chapter drafts and offering insightful feedback.

![]() Thank you to the artists with lived experience of homelessness, whose artwork greatly enriched the content of this book.

Thank you to the artists with lived experience of homelessness, whose artwork greatly enriched the content of this book.

![]() Thank you to the participants who provided the quotes we used in the cards throughout this book.

Thank you to the participants who provided the quotes we used in the cards throughout this book.

![]() Thank you to all of the researchers who contributed their time and knowledge to this book.

Thank you to all of the researchers who contributed their time and knowledge to this book.

5

This resource was created by a whole team of people working together on different aspects. Some of us you will see on camera, but much of the work happened “behind the scenes.” Here is the cast of (sometimes whacky!) characters that produced this book.

NICOLE WHITMORE

JAMES DAVY

CYNDI GILMER

KRISTY BUCCIERI

STEPHANIE FERGUSON

JAMES BAILEY

JOSH ANDREWS

STEPHANIE VASKO

BRAD KEIZERWAARD

CARTER TONGS

6

Our team would like to express our appreciation for the 26 researchers who participated in recorded conversations with us about homelessness in Canada. The collective knowledge of this group is tremendous and provides a depth of understanding we could not have achieved on our own. Below we provide a brief biography of the researchers you will hear from throughout this book. We encourage you to learn more about the amazing work they are doing and to see the reference list for some of their most recent publications.

Please note that researchers have approved their own video segments but have not reviewed each other’s videos nor the written content of the book. We thoroughly enjoyed speaking with these researchers and are confident you will find them engaging as well. Taken together, we have collected 15 hours of their expert reflections on some pretty tough questions. Keep reading to learn more about homelessness in Canada, from the streets to the classroom.

Dr. Alex Abramovich is an Independent Scientist with the Institute for Mental Health Policy Research at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health.

Abramovich Interview – YouTube Playlist

Dr. Tim Aubry is a Professor of Psychology at the University of Ottawa.

Aubry Interview – YouTube Playlist

Dr. Erin Dej is an Assistant Professor with the Department of Criminology at Wilfrid Laurier University.

Dej Interview – YouTube Playlist

Dr. John Ecker is the Research Manager with the MAP Centre for Urban Health Solutions atUnity Health Toronto.

Ecker Interview – YouTube Playlist

Dr. Nick Falvo is a Research Consultant at Nick Falvo Consulting.

Falvo Interview – YouTube Playlist

Dr. David Firang is an Assistant Professor with the Department of Social Work at Trent University.

Firang Interview – YouTube Playlist

Dr. Cheryl Forchuk is a Research Chair in Aging, Mental Health, Rehabilitation and Recovery at Western University.

Forchuk Interview – YouTube Playlist

Dr. Tyler Frederick is an Associate Professor in Criminology and Justice at Ontario Tech University.

Frederick Interview – YouTube Playlist

Dr. Stephen Gaetz is the President of the Canadian Observatory on Homelessness at York University.

Gaetz Interview – YouTube Playlist

Dr. Jonathan Greene is an Associate Professor in Political Studies at Trent University.

Greene Interview – YouTube Playlist

Dr. Stephen Hwang is the Director of the MAP Centre for Urban Solutions at St. Michael’s Hospital.

Hwang Interview – YouTube Playlist

Dr. Jeff Karabanow is the Associate Director and a Professor with the School of Social Work at Dalhousie University.

Karabanow Interview – YouTube Playlist

Dr. Jacqueline Kennelly is a Professor with the Department of Sociology and Anthropology at Carleton University.

Kennelly Interview – YouTube Playlist

Dr. Nick Kerman is a Post-Doctoral Fellow at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health.

Kerman Interview – YouTube Playlist

Dr. Sean Kidd is the Chief of the Psychology Division at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health.

Kidd Interview – YouTube Playlist

Dr. Katrina Milaney is an Associate Professor in Community Health Sciences at the University of Calgary.

Milaney Interview – YouTube Playlist

Dr. Naomi Nichols is a Tier 2 Canada Research Chair with the Department of Sociology at Trent University.

Dr. Bill O’Grady is a Professor with the Department of Sociology and Anthropology at the University of Guelph.

O’Grady Interview – YouTube Playlist

Dr. Abe Oudshoorn is an Associate Professor with the Arthur Labatt Family School of Nursing at Western University.

Oudshoorn Interview – YouTube Playlist

Dr. Bernie Pauly is a Professor with theSchool of Nursing at the University of Victoria.

Pauly Interview – YouTube Playlist

Jessica Rumboldt is a Post-Doctoral Fellow in Indigenous Homelessness at York University.

Rumboldt Interview – YouTube Playlist

Dr. Rebecca Schiff is the Chair and Associate Professor in Health Sciences at Lakehead University.

Schiff Interview – YouTube Playlist

Dr. Kaitlin Schwan is the Director of Research, with Making the Shift at the Canadian Observatory on Homelessness.

Schwan Interview – YouTube Playlist

Dr. Kelli Stajduhar is a Professor with the School of Nursing at the University of Victoria.

Stajduhar Interview – YouTube Playlist

Dr. Naomi Thulien is a Scientist with the Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute at St. Michael’s Hospital.

Thulien Interview – YouTube Playlist

Dr. Jeannette Waegemakers Schiff is a Professor with the School of Social Work at the University of Calgary.

I

Let’s play a game.

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/homelessness/?p=512#h5p-20

How did you do? If indeed you found this game to be a little too easy, then you have demonstrated an understanding of the term ‘home’ and the subjective meanings we collectively attach to it in society. Home is thought to be a safe and secure internal place that protects us from the dangerous outside world. But is it?

For many Canadians, the home is not a place of refuge but rather a place fraught with conflict, stress, oppression, and/or insecurity. Home can be many things to people, some which are good and some which are not. The reasons that people leave or are pushed out of their homes are varied and complex. Despite a common stereotype that people choose homelessness, very rarely is this the case. Rather, people sometimes come to a point in their lives where homelessness is the only alternative they have. It is not a good one, but it may be the only one.

1

In this chapter you are invited to enter into an ongoing dialogue about what homelessness is, how it was created, and what we can do to prevent it. Many of the themes identified here will re-emerge throughout the chapters that follow. As you begin to engage with the study of homelessness in Canada, you are encouraged to reflect upon three key questions guiding this chapter’s learning objectives.

As you move through this chapter it is beneficial to keep in mind that homelessness is rarely an individual choice, but rather results from circumstances in a person’s life that are often beyond their control. You are encouraged to work through this material with an open mind about what you read, hear, and see, even if (or particularly if) it contradicts previous stereotypical images that might have shaped your perceptions about homelessness and homeless people. Read on to learn more about what homelessness means, how we gather information about it, and why we all would benefit from shifting our collective focus towards prevention.

2

We begin this chapter by presenting two composite scenarios that reflect real-world experiences of homelessness in Canada. As you read through these scenarios, you are encouraged to adopt both an empathic perspective, to consider your own response(s) within the scenarios, and a critical perspective, to think about how the scenarios represent larger issues impacting people in our society.

After pausing respond to reflection questions, we will endeavour to answer each question posed in the learning objectives. What is homelessness? How do we know what we know about homelessness? Why does homelessness prevention matter? Throughout this chapter, we will examine these three questions using academic literature, featured articles, lived experience representation, multi-media activities, and virtual guest lectures from some of Canada’s leading homelessness researchers.

At the end of the chapter, we will return to the scenarios presented at the beginning and reconsider them in light of what has been learned. Together we will see how a framework of being trauma-informed, person-centred, socially inclusive, and situated within the social determinants of health is critical for understanding homelessness in Canada. These concepts will re-emerge in each chapter throughout this book to demonstrate the complexity and inter-connected nature of these issues.

3

As you being to learn about homelessness and the complex ways in which it is experienced, we encourage you to begin with these real life composite scenarios. Take a moment here to pause and consider these people’s experiences.

John

John is a 45-year-old male who lives downtown in a large city. During the day he can be found on the same street corner, outside a Tim Horton’s sitting with his dog Rex on a flattened cardboard box. He has an empty Tim’s cup in front of him and a small handwritten sign asking for money. He is often asleep or dozing and people walk around him without acknowledging that he is there. Some people drop change into his cup. John spends his nights walking the back alleys downtown attempting to avoid both the police and other street people. He knows that if he stops to try and sleep in a vestibule at a bank or in an underground parking garage he will be hassled by the police. He’ll be given yet another ticket he can’t pay.

Tasha and Raoul

Tasha and Raoul are a young couple. Tasha is new to Canada and her immigration status is in limbo. They are living in an old trailer parked in a wooded area on a field owned by an elderly farmer. The lot is 10 kilometers outside of a small rural town. They have no hydro and no running water. They have rigged up an outdoor shower using buckets of water from a nearby stream. They have four dogs. They rely on hitchhiking for rides into town as they have no other transportation. Tasha has a chronic health issue that requires daily medication. Her overall health is not good and not well managed.

With these scenarios fresh in your mind, consider these reflection questions. You may wish to record your answers before moving on to the next section. We will return to these scenarios again at the end of the chapter.

Reflection Questions

4

As we sat down to write this book, we decided to frame each chapter around a set of questions. While this was an organizational choice, it was also an intentional choice to encourage you to begin your studies with questions at the forefront of your mind. We encourage you to take a moment at the beginning of each section to think about how you would answer the question posed in the title. In this instance, what is homelessness? We have asked this exact question to a series of leading homelessness researchers from across the country, whose work you will also have the opportunity to read.

Before you hear from them, take a moment to answer this question for yourself and see how your definition compares with theirs. This activity is useful in documenting your own starting point and is for your eyes only. It will not be submitted to your instructor, so you should feel free to write as little or as much as you wish to answer the question.

How to complete this activity and save your work: Type your response to the question in the box below. When you are done answering the question navigate to the ‘Export’ page to download and save your response. If you prefer to work in a Word document offline you can skip right to the Export section and download a Word document with this question there.

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/homelessness/?p=554#h5p-25

A 1993 book entitled, Down and out in Canada: Homeless Canadians opens with the quote, “In 1990s Canada, the problem of homelessness remains an enigma. The homeless are largely a social crisis for which there is no audience. There is little political currency to be made in championing the cause of the weakest in our society, those who are without benefit of shelter” (O’Reilly-Fleming, 1993, pg.1). Is it still the case that homelessness remains an enigma that no one pays attention to 30 years later? As you will see, interviews with Canadian homelessness researchers show that in fact homelessness is well understood despite its complexity.

What remains the same is O’Reilly-Fleming’s (1993) observation that many Canadians know very little about homelessness and have stereotypical images drawn from momentary and often fearful glimpses on downtown streets or from random media images. These themes emerged as we sat down to speak independently with Dr. Stephen Hwang and Dr. Stephen Gaetz about how they would each define homelessness.

When the videos in this ebook are almost done playing, the message “Stop the video now” will appear in the top left corner. This is a reminder for those who have the Autoplay setting turned on to manually pause the video when the speakers are done to avoid having it autoplay through to the next video. This message will appear in all researcher videos throughout the ebook.

When the videos in this ebook are almost done playing, the message “Stop the video now” will appear in the top left corner. This is a reminder for those who have the Autoplay setting turned on to manually pause the video when the speakers are done to avoid having it autoplay through to the next video. This message will appear in all researcher videos throughout the ebook.

Note: Viewers may still need to use their discretion in stopping other YouTube content such as ads.

In this video, Dr. Stephen Hwang explains that homelessness can be thought of as being unhoused and not having a stable place of one’s own to live. He argues that homelessness is sometimes mistakenly viewed as an unusual state, when it is really just a continuum of housing instability and inadequacy that are part of a larger phenomenon. He offers the analogy that we recognize the complexity of nutrition as not just being about whether a person eats or starves to death, but rather we consider whether people have access to quality food at an affordable price. By thinking about homelessness in narrow ways as whether someone is absolutely homeless or not, we miss the larger issue of whether people have access to quality housing at an affordable price. Dr. Hwang notes that there are different types of homelessness that exist along a continuum, and as the definition gets broader more people are included, who are difficult to identify and engage with. He concludes that rather than becoming fixated on one specific definition of homelessness, we should focus more on being clear about what we mean when we use the term. This video is 2:36 in length and has closed captions available in English.

Key Takeaways – Dr. Stephen Hwang: What is homelessness?

In this video, Dr. Stephen Gaetz argues that the category of homelessness is something we came up with to name a problem we created. He notes that as a society we define people by their housing status and then make judgements and infantilize them because of it, on the basis that they are a “homeless person” and therefore different somehow. Dr. Gaetz counters that it is important to begin with the assumption that this is a human being with rights. He encourages us to consider what a developing adolescent or adult experiencing homelessness needs and realize that it is not all that different than the needs of someone who has housing. Dr. Gaetz concludes that we must move towards a greater recognition that people are people, and homelessness is part of a person’s story but that it does not define them. This video is 2:16 in length and has closed captions available in English.

Key Takeaways – Dr. Stephen Gaetz: Creating the homeless person

Dr. Hwang and Dr. Gaetz both make the important point that homelessness does not define a person’s identity. Rather than thinking about homelessness as an unusual state, we must begin with the understanding that it is an experience had by human beings with human rights. The following video, Do you see me? was created by I Heart Home and explores the stories of people living in Calgary, Alberta. As you watch this video we encourage you to remember the advice from Dr. Gaetz, to begin with the assumption that this is a human being with rights, and then go from there.

Keeping at the forefront of our minds that homelessness is an issue impacting human beings who have rights, we can now shift towards exploring the definitions. Here we begin with videos from Dr. Tim Aubry and Dr. Jonathan Greene, where they each provide an overview of the types of homelessness people commonly experience and the different factors that need to be considered in formulating a definition.

In this video, Dr. Tim Aubry explains that homelessness is often defined similarly in research and practice, as occurring when a person lacks their own place that is safe, sheltered, and without short-term length of stay limitations. He notes that there are different types of homelessness, including people residing in emergency shelters, sleeping rough, staying in encampments, or more hidden by staying temporarily with friends or family. Dr. Aubry concludes by discussing the Canadian definition, which further stretches to also include considerations of people who are at-risk of homelessness. This video is 2:38 in length and has closed captions available in English.

Key Takeaways – Dr. Tim Aubry: What is homelessness?

In this video, Dr. Jonathan Greene explains that how we define homelessness as a concept, idea, and state of being changes across locations and evolves over time. He argues that since our understandings of homelessness are informed by the political, cultural, and social forces at play, there is no straightforward answer. Dr. Greene notes that currently many government indicators of homelessness reference housing, such as whether there is an adequate supply, but that this is a relatively new approach as Professor David Hulchanski shows, that emerged in the 1980s. Dr. Greene notes that in contemporary Canadian policies, such as the Reaching Home strategy, the government has adopted a continuum approach that incorporates absolutely homeless, emergency sheltered, being insecurely housed, and being at-risk of homelessness. He draws our attention to the temporal aspects of definitions as well, noting that the recent construction of chronic, episodic, and transitional homelessness has created three priority populations. Dr. Greene concludes that the definition of homelessness changes between locations and evolves over time, but that across these we want to think about the ideas of house and home, locations people can be in, and how homelessness can be experienced differently by different individuals and households. This video is 6:05 in length and has closed captions available in English.

Key Takeaways – Dr. Jonathan Greene: What is homelessness?

As we heard from Dr. Aubry and Dr. Greene, there are different types of homelessness that people may experience. These are the result of structural factors, systems failures, and individual circumstances. Take a moment to explore these further in this interactive module from the Homeless Hub entitled Why do people become homeless? You may also wish to share this with others through your social networks and invite them to join the conversation. Be sure to follow us on Twitter using @Homeless_ebook and #UnderstandingHomelessness.

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/homelessness/?p=554#h5p-26

There are many factors that contribute to homelessness and the experience is different for every person. Yet, there is considerable value in recognizing the shared characteristics. In 2012 the Canadian Observatory on Homelessness released a definition that was collaboratively developed and has been widely adopted in research, policy, and practice across the country (Gaetz et al., 2012). Here we discuss this definition with Dr. Stephen Gaetz, President of the Canadian Observatory on Homelessness. Following this video, we encourage you to explore the definition further with an introductory video and then a review of the document itself.

In this video, Dr. Stephen Gaetz explains that homelessness describes a situation in which people do not have adequate, safe, and affordable housing, nor the immediate prospect of getting it. It does not arise from a person’s individual characteristics but rather is produced and sustained by society. He notes that blaming individuals for their homelessness fails to hold society responsible for its need to do something about the problem. Dr. Gaetz concludes by discussing the Canadian definition of homelessness, as a document that provides common language and a typology that has been widely adopted by researchers and governments. This video is 3:03 in length and has closed captions available in English.

Key Takeaways – Dr. Stephen Gaetz: What is homelessness?

Gaetz, S., Barr, C., Friesen, A., Harris, B., Hill, C., Kovacs-Burns, K., Pauly, B., Pearce, B., Turner, A., & Marsolais, A. (2012) Canadian definition of homelessness. Toronto: Canadian Observatory on Homelessness Press.

Canadian Definition of Homelessness | The Homeless Hub

Now that you have had the chance to read through it, what do you think of the Canadian Definition of Homelessness? Is there anything you would add to it or take away?

Now that you have had the chance to read through it, what do you think of the Canadian Definition of Homelessness? Is there anything you would add to it or take away?

As we posed the question, “What is homelessness?” to different researchers, the Canadian definition emerged as a key document that shapes the way we collectively have come to think about homeless as existing along a continuum. The Canadian definition also serves as a starting point for thinking about the experiences of different populations and about housing as a fundamental human right.

Here we share our conversations with Dr. John Ecker, Dr. Kaitlin Schwan, and Dr. Erin Dej, where they discuss how the Canadian definition of homelessness has influenced their understandings of what homelessness means. You will also hear reference to the Indigenous definition of homelessness in Canada, published by scholar Jesse Thistle (2017), which is discussed in detail in the chapter on Indigenous Studies.

In this video, Dr. John Ecker offers a comprehensive definition of homelessness as the lack of adequate, suitable, and affordable housing, and as a violation of the human right to housing. Dr. Ecker expands by discussing the four parts of the Canadian Observatory on Homelessness’ definition, which includes people who are unsheltered, emergency sheltered, provisionally accommodated, and at-risk of homelessness. He notes that it is important to think about different subgroups who experience homelessness at higher rates or in unique ways, such as women, families, and youth. Dr. Ecker concludes by drawing attention to how these definitions are westernized understandings, and points towards Jesse Thistle’s definition of Indigenous homelessness as being a useful resource for thinking about homelessness in different ways. This video is 3:32 in length and has closed captions available in English.

Key Takeaways – Dr. John Ecker: What is homelessness?

In this video, Dr. Kaitlin Schwan explains that homelessness is a condition where people lack access to permanent and affordable housing that is safe, secure, and able to meet their needs. She notes that homelessness exists along a continuum, from absolutely homeless on one end to being in core housing need on the other. Dr. Schwan argues that within a Canadian context it is critical to understand Indigenous homelessness and points towards the definition developed by Jesse Thistle that identifies 12 dimensions. Dr. Schwan concludes by noting that the 2019 National Housing Strategy Act declared housing to be a human right, and that we need to understand homelessness as a violation of this right. This video is 3:19 in length and has closed captions available in English.

Key Takeaways – Dr. Kaitlin Schwan: What is homelessness?

In this video, Dr. Erin Dej explains the four elements that make up the Canadian Observatory on Homelessness’ definition of homelessness. She notes that the first two elements – absolutely homeless and emergency sheltered – are what people most often associate with homelessness. However, she notes it is important to pay attention to the additional elements, which sometimes get overlooked. Those who are provisionally accommodated have somewhere to stay but it is temporary, such as transitional housing, couch surfing, and leaving a correctional or hospital facility without identified housing. Dr. Dej argues we must pay special attention to those at-risk of homelessness because while they have somewhere to stay it is not safe, affordable, or acceptable, such as those who are facing eviction, living in overcrowded housing, and/or experiencing domestic violence. Dr. Dej concludes that we can also learn about people at-risk of homelessness by applying the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation’s definition, of those spending 30% or more on housing as being in core housing need and one crisis away from homelessness. This video is 3:34 in length and has closed captions available in English.

Key Takeaways – Dr. Erin Dej: What is homelessness?

Throughout this book, we will share quotes from a research study we conducted in two small / rural towns in Ontario, as one way to provide space for the voices of people with lived experience. The first of these cards is presented below. To learn more about this project and the participants, please visit the Trent University Homelessness Research Collective (2019) website.

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/homelessness/?p=554#h5p-27

A key component of the Canadian definition of homelessness is that it includes people who are at–risk of losing their housing, due to issues such as spending too much of their income on rent, living in overcrowded conditions, or living in housing that is not good quality. Whether or not the definition should include people who are at-risk has been a hotly debated topic, with some arguing that a broad definition is needed to allow us to focus on prevention, and others arguing a narrow definition allows us to focus resources on those who are most in need.

Dr. Nick Falvo and Dr. Jeannette Waegemakers Schiff both discuss the issue of risk and vulnerability as factors that need to be considered carefully in crafting a definition of homelessness. As you watch these conversations, consider where you stand on this debate. Should the definition of homelessness include people who are at imminent risk of losing their housing?

Dr. Nick Falvo and Dr. Jeannette Waegemakers Schiff both discuss the issue of risk and vulnerability as factors that need to be considered carefully in crafting a definition of homelessness. As you watch these conversations, consider where you stand on this debate. Should the definition of homelessness include people who are at imminent risk of losing their housing? In this video, Dr. Nick Falvo defines homelessness as relating to people living in an emergency shelter, outside, or in a structure not meant for human habitation. He notes that these individuals tend to be included in point-in-time counts. Beyond this, he explains, there are also individuals who meet the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation’s definition of core housing need. Dr. Falvo argues that while a narrow definition is not as widely accepted, for fear those in housing need will be forgotten, it is possible to have a narrow and broad definition that reflects these housing distinctions. This video is 1:21 in length and has closed captions available in English.

Key Takeaways – Dr. Nick Falvo: What is homelessness?

In this video, Dr. Jeannette Waegemakers Schiff explains that to understand the risk of homelessness we must consider people’s access to social and economic protections. There are some people who are relatively immune to homelessness because they have secure jobs and strong cash reserves that will allow them to become rehoused again quickly if they lose their housing. However, Dr. Waegemakers Schiff notes there is a large proportion of society who do not have the same supports to protect them, including people with adverse psychosocial issues, youth who have been displaced and alienated from their homes, women who experience domestic violence, and people with serious physical conditions who are reliant on disability income supports. Dr. Waegemakers Schiff argues that the COVID-19 pandemic exposed many pre-existing vulnerabilities and that who is at risk and who is not, casts the great divide. She concludes by discussing recent research into the vulnerability of post-secondary students during the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly as measures closed spaces they rely on for food and shelter. This video is 4:54 in length and has closed captions available in English.

Key Takeaways – Dr. Jeannette Waegemakers Schiff: Defining vulnerability

In this section, we have explored the question, “What is homelessness?” At the beginning, we asked you to write your own response and to keep it in mind as you progressed through the material. We encourage you now to look back at your response, or simply bring it to mind, and consider how it compares to what you have seen, heard, and read. Has your definition of homelessness changed? If so, how would you answer this question now?

When asked to discuss what homelessness is, researchers in the field spoke about many important issues. They began by explaining that homelessness is not an unusual state or a defining characteristic, but rather something that happens to human beings. They discussed the different types of homelessness, the various causes, and the factors that need to be considered in creating a definition. We learned from these researchers that there is a Canadian definition of homelessness that was published in 2012, that has been influential in research, policy, and practice. This definition provides a typology for thinking about homelessness as a continuum, rather than a dichotomy of being ‘homeless or housed.’ The Canadian definition includes those who are at-risk of homelessness, which other definitions classify as those who pay more than 30% of their income, making them in core housing need.

When students sign up to take a course on homelessness they often question what there is to know that could take an entire semester to learn. We hope that even this brief introductory section demonstrates the complexity of homelessness, what we already know, and how much more there is still to learn. Join us in the next section, as we consider how we know what we know about homelessness.

Click the link below to listen to all of the researchers answer the question “What is Homelessness?” in audio format on our podcast!

5

As you begin this section, we encourage you to think about the question of how we know what we know about homelessness. This question, like many we will explore throughout this book, seems deceptively simple because we may confuse our own opinions and beliefs with validated knowledge. What we know comes from many different sources, some more reliable than others. Before you hear from the researchers in this section, we encourage you to take a moment to jot down your own thoughts. You may also want to consider related questions, such as where you have learned about homelessness, like your home or school, what experiences you have had that might have influenced your perceptions, and whether you feel the information you have received comes from credible sources. Remember that your answer here is just for your reflection, it may be as brief or long as you wish, and it is not going to be seen by others.

How to complete this activity and save your work: Type your response to the question in the box below. When you are done answering the question navigate to the ‘Export’ page to download and save your response. If you prefer to work in a Word document offline you can skip right to the Export section and download a Word document with this question there.

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/homelessness/?p=556#h5p-28

It may come as no surprise to you that much of what we know about homelessness in Canada comes from research over the past 40 years. The body of research that has developed over time reflects the different methodologies and approaches researchers have used to learn about this issue. You may be interested to know that much of the interactive content for this book comes from our partners at the Canadian Observatory on Homelessness, which is the largest national research institute devoted to homelessness in Canada. They are also the curator of the Homeless Hub, an online library of over 30,000 resources.

Throughout this book, you will get to hear directly from many influential researchers in the field of homelessness, who have helped to create the research that shapes public policy decisions today. As our knowledge continually evolves, we have made the conscious decision to focus on studies that were published by Canadian researchers within the 5 years preceding publication of this book. In the next set of videos, you will hear from Dr. Kaitlin Schwan and Dr. John Ecker, who provide an overview of how research has changed over time, the importance of peer-review and evaluation, and the impact on modern day policy.

In this video, Dr. Kaitlin Schwan explains that mass homelessness, as we know it today in Canada, started to emerge in the 1980s. In response, we have tried many policy and program interventions, which have been evaluated using a range of research methods. The knowledge from these studies has been synthesized in peer-reviewed journals and made publicly available, such as through the Homeless Hub website. Dr. Schwan notes the key to understanding homelessness is listening to people with lived expertise, as they have experienced the ways various systems and structures operate to create conditions for those living without housing. This video is 1:46 in length and has closed captions available in English.

Key Takeaways – Dr. Kaitlin Schwan: How do we know what we know about homelessness?

In this video, Dr. John Ecker discusses the trajectory of homelessness research, from an early focus on investigating the causes and consequences, to a modern day focus on applied research into identifying solutions and empowering people with lived experience. He notes that there are many different types of research, and that they are often published in peer-reviewed journal articles which allows for confidence in what is being reported. Dr. Ecker concludes by acknowledging the important work of grassroots advocacy organizations, particularly those led by individuals with lived experience, in providing information and resources to the general public and to policy makers. This video is 4:04 in length and has closed captions available in English.

Key Takeaways – Dr. John Ecker: How do we know what we know about homelessness?

We heard from Dr. Schwan and Dr. Ecker that research on homelessness has changed over the past 30 to 40 years. In 1993 O’Reilly-Fleming wrote, “One of the great difficulties which confronts any attempt to deal with and analyse the problem of homelessness in Canadian society is the lack of consistent and reliable data on both the number and composition of the homeless population” (pg.11). Trying to learn about the number of people experiencing homelessness in any given community is still challenging today because of hidden homelessness. Some populations are particularly difficult to reach and enumerate, such as Indigenous individuals, refugees and new Canadians, women, and youth. For hidden populations, multi-methods like respondent-driven sampling may be needed in addition to more standard census data collection (Rotondi et al., 2017).

One of the main changes that has occurred in the past decade is the development of point-in-time [PIT] counts to better identify the number of people experiencing homelessness in a given community. These counts are done on a set day and involve volunteers going to shelters, drop-in centres, and public places like city parks to collect information about the people within these spaces who are experiencing homelessness. These counts do not identify every person, and still frequently miss the hidden populations, but they are one approach we have to better understand the occurrence of homelessness in communities across Canada. Learn more with this brief video from Employment and Social Development Canada.

Here Dr. Erin Dej explains more about point-in-time counts, and why it is important we recognize that not all populations will be equally represented in these efforts.

In this video, Dr. Erin Dej explains that the emergence of homelessness research in Canada really began with the rise in mass homelessness in the 1990s. Researchers at the time focused on individuals to see who was experiencing homelessness and why. Over time, this research has evolved to focus on broader systemic and structural causes of homelessness. Dr. Dej notes that more recently we have also learned about homelessness through point-in-time counts in which cities do a one-day count of all the people they can find who are experiencing homelessness. While these counts provide valuable information about homelessness within cities and over years, Dr. Dej also cautions that they tend to miss hidden populations such as women, LGBTQ2S+ persons, youth, and Indigenous persons. This video is 3:43 in length and has closed captions available in English.

Key Takeaways – Dr. Erin Dej: How do we know what we know about homelessness?

Policy makers often use point-in-time data in their decision-making about what programs will get funded in a given community, but this data often misses key populations like women, LGBTQ2S+ persons, youth, and Indigenous people. How do you think we can improve our efforts to identify these hidden populations to policy makers are aware of their unique needs?

Policy makers often use point-in-time data in their decision-making about what programs will get funded in a given community, but this data often misses key populations like women, LGBTQ2S+ persons, youth, and Indigenous people. How do you think we can improve our efforts to identify these hidden populations to policy makers are aware of their unique needs?

Collecting data is an important way that ‘we know what we know’ about homelessness. In addition to point-in-time counts, researchers have also applied mathematical models to better determine where people are located in time across homelessness and housed states (Fisher, Mago, & Latimer, 2020) and used health administrative databases to identify people experiencing homelessness over time (Richard et al., 2019). Likewise, shelter use data can provide valuable information, such as comparisons between usage in different cities (Dutton & Jadidzadeh, 2019) and between populations like single adults, youth, and families (Jadidzadeh & Kneebone, 2018).

According to Echenberg and Munn-Rivard (2020), “Defining and enumerating homelessness is essential in order to understand the nature and extent of the problem, who is affected by it and how to address it” (pg.i). They continue by noting that despite the visibility of homelessness in Canada, it is challenging to count people who lack a permanent address, often remain hidden, and may move in and out of homelessness. Take a moment to read their background paper below, to learn more about the different types of data collection methods used, and how they help us know more about the problem of homelessness in Canada.

Echenberg, H., & Munn-Rivard, L. (2020). Defining and enumerating homelessness in Canada: Background paper. Ottawa, ON: Library of Parliament.

Echenberg, H., & Munn-Rivard, L. (2020). Defining and enumerating homelessness in Canada: Background paper. Ottawa, ON: Library of Parliament.

Background Paper: Defining and Enumerating Homelessness in Canada (parl.ca)

As you have just read, there are many different ways we collect data about who is experiencing homelessness. In the next video Dr. Stephen Gaetz expands on this and cautions that while this information is valuable, it only tells us about people who are visibly homeless and in crisis at that moment in time. Listen in as he discusses the limitations of our current data collection approach.

In this video, Dr. Stephen Gaetz explains that much of the data we collect about people experiencing homelessness comes from administrative data, national point-in-time counts, and shelter records. He notes that while we are getting better at collecting data, the information only tells us about people in crisis, such as those who touch the system. Dr. Gaetz explains that our data collection efforts are improving but are still focused on people while in homelessness, and somewhat on exits from homelessness, but are not currently designed to provide information about homelessness prevention. This video is 2:04 in length and has closed captions available in English.

Key Takeaways – Dr. Stephen Gaetz: How do we know what we know about homelessness?

Data collection are important strategies for enumerating the extent of homelessness in Canada and for developing policies thatinform best-practice approaches. Yet, what is most valuable for understanding homelessness in Canada is that we listen to the knowledge of people with lived experience. The importance of authentic lived experience representation has been a central theme throughout the researcher videos, such as in our conversation with Dr. Nick Falvo.

In this video, Dr. Nick Falvo discusses the range of sources of information about homelessness. He notes that it is important to talk to people with lived experience, as much of what we know comes from hearing their stories. Dr. Falvo also notes people who do frontline work at the community level are incredible sources of information. What we know about homelessness also comes from government-coordinated data gathering efforts and researchers located in universities and the community. Dr. Falvo concludes that social media can be an important source of information but that we must be cautious about believing all the information we receive. This video is 2:10 in length and has closed captions available in English.

Key Takeaways – Dr. Nick Falvo: How do we know what we know about homelessness?

Today it is common for people with lived experience of homelessness to be paid members of research teams and to inform all aspects of the project’s design, data collection, and analysis. This brief video from United Way Ottawa demonstrates the importance of lived experience driven research.

Developing our understanding of homelessness – how we know what we know – requires strong partnerships between researchers, people with lived experience, policy makers, and the community. Dr. Cheryl Forchuk speaks about the importance of community partnerships in all ofher research projects.

In this video, filmed at a hospital during the COVID-19 pandemic, Dr. Cheryl Forchuk discusses the importance of relationships with community partners, including people who have lived experience, because addressing homelessness is not something anyone can do alone. She notes that these relationships are essential so people can work together to come up with creative solutions. Dr. Forchuk argues that while community partners may know an issue exists, it is often difficult for them to get policy change unless they can point to data to help increase the political will. This video is 2:44 in length and has closed captions available in English.

Key Takeaways – Dr. Cheryl Forchuk: Collecting data with community partners

When people who have lived experience of homelessness are asked to speak about the issues impacting their lives, prominent themes include a lack of money, home, privacy, and support, discrimination based on Indigeneity or African descent, living with mental illness and/or addiction, the lived impact of rent, housing, and mortgage policies, and the need for greater awareness of government support systems and services (Ahajumobi & Anderson, 2020).

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/homelessness/?p=556#h5p-30

Listening to people with lived experience is critical to understanding homelessness and generating knowledgethat could be used to inform sound policies. However, while there are active efforts to involve people with lived experience in research, this may not always translate into their voices being included in policy. Benmarhnia et al., (2018) caution that the concept of ‘vulnerability’ is often used in shaping public policies, but the populations who are identified as vulnerable are rarely consulted about whether the term applies to them. Terms like vulnerability, sensitivity, and marginality may be applied indiscriminately (Van den Hoonaard, 2018).In the next video, Dr. Bernie Pauly speaks about how we can move beyond listening to people with lived experience, to having real and authentic engagement.

In this video, Dr. Bernadette [Bernie] Pauly advocates that in whatever role we have, whether practice, policy, or research, it is essential to engage with people who have lived and living experience of homelessness in real and authentic ways. She notes that it is not enough to listen, but that we must believe people when they tell their stories and not be judgemental. Dr. Pauly encourages people in planning and leadership roles to ask themselves how they are engaging with people who have lived experience in a way where they are recognized partners. She concludes that the knowledge they share may be hard to hear, but that we must recognize the system is broken and truly listening is the only way to fix it. This video is 2:45 in length and has closed captions available in English.

Key Takeaways – Dr. Bernie Pauly: The critical importance of listening to people with lived experience

Zhang and Kteily-Hawa (2018) write that telling one’s story can be an act of agency and advocacy for human rights and personhood. We have heard from many researchers about the importance of listening to people with lived experience. What do you think governments and policy makers can do to move from token engagement to authentic engagement?

Zhang and Kteily-Hawa (2018) write that telling one’s story can be an act of agency and advocacy for human rights and personhood. We have heard from many researchers about the importance of listening to people with lived experience. What do you think governments and policy makers can do to move from token engagement to authentic engagement?

In this section, we considered the question, “How do we know what we know about homelessness?” Through a series of videos and readings, we can see that our knowledge comes from many different sources. We have seen how research, point-in-time counts, and administrative data, such as shelter usage and health records, can be used to better understand the scope of homelessness and to inform policy decisions. Along with these sources, you may recall we also saw some of the shortcomings, like the hidden populations that tend to be missed and the increased efforts that are needed to learn about people at risk of homelessness.

We concluded this section by focusing on the critical importance of truly listening to people with lived experience. While they are the experts, they are not always consulted in authentic ways that respect the knowledge they hold. How we know what we know is important to keep in your mind as you move through the book and continue to learn about homelessness from these various sources.

Click the link below to listen to all of the researchers answer the question “How do we know what we know about homelessness?” in audio format on our podcast!

Listen to “How do we know what we know about homelessness?” on Spreaker

6

Canada has gone through three stages to try to reduce homelessness, including an emergency response in the 1990s, an implementation of community plans combined with Housing First initiatives, and more recently is in the beginning stages of moving towards a stronger focus on prevention (Gaetz, 2020). In this section we take a closer look at what homelessness prevention is and why it matters. Before you begin this section, please take a moment to write down your own thoughts about homelessness prevention below.

How to complete this activity and save your work: Type your response to the question in the box below. When you are done answering the question navigate to the ‘Export’ page to download and save your response. If you prefer to work in a Word document offline you can skip right to the Export section and download a Word document with this question there.

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/homelessness/?p=558#h5p-31

Homelessness is a trauma that has long-term detrimental effects on the people who experience it. We know from research that the duration of a person’s homelessness can negatively influence their housing outcomes, which is a strong argument for prevention and early intervention that decreases the amount of time a person spends experiencing homelessness (Chen, Cooper, & Rivier, 2021). In these three videos youth homelessness researchers Dr. Naomi Nichols, Dr. Alex Abramovich, and Dr. Kaitlin Schwan speak about the negative impacts of homelessness and how difficult it is to move people out after they become entrenched.

In this video, Dr. Naomi Nichols argues that prevention matters because homelessness erodes people’s well-being and their connections to people and places. She notes that homelessness subjects people to discrimination and stigma, which for youth in particular can have detrimental effects on their physical and mental wellness, as well as their connections to school, work, and other protective institutions. Dr. Nichols further argues that homelessness erodes a person’s sense of safety and while feeling unsafe is not good for anyone, it is particularly problematic for young people to have chronic stress in their bodies at a critical time in their adolescent development. This video is 3:06 in length and has closed captions available in English.

Key Takeaways – Dr. Naomi Nichols: Why does prevention matter?

In this video, Dr. Alex Abramovich explains that we have been talking more about prevention in recent years, but it is still not fully understood. He notes that it can be difficult to support people in successfully exiting homelessness and provides the example of LGBTQ2S+ youth who often have to have something tragic happen before they are provided significant support to exit homelessness. Dr. Abramovich cautions that this is a reactionary response and that if we put more energy and emphasis into prevention, we could help people avoid trauma and instead focus on supporting their long-term health and well-being. This video is 1:51 in length and has closed captions available in English.

Key Takeaways – Dr. Alex Abramovich: Why does homelessness prevention matter?

In this video, Dr. Kaitlin Schwan explains that in Canada, our response to homelessness is emergency-based and that supports are provided on the basis of demonstrating high levels of need. The design of this system is such that people must go through a lot of harm and trauma before the system kicks in to help them. Dr. Schwan provides the example of working with young people who have been unable to access programs until they reached 6 months on the street. She argues that in this time, they can accumulate multiple harms and traumas. Dr. Schwan discusses how homelessness shapes the trajectory of a person’s life and can have lasting inter-generational effects. This is evidenced through the looping effect of involvement in the child welfare system across generations, which particularly impacts racialized and Indigenous communities, making prevention a particularly important equity-based approach. Dr. Schwan concludes that our current emergency response is expensive, and that prevention is the way forward to align with our commitments to human rights in Canada. This video is 4:35 in length and has closed captions available in English.

Key Takeaways – Dr. Kaitlin Schwan: Why does homelessness prevention matter?

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/homelessness/?p=558#h5p-32

Our current response to homelessness is a crisis-based one that uses emergency services, like shelters, to help people only once they are on the far end of the homelessness continuum. This model is flawed in many ways, not least of all because of the poor quality of life it creates for service users.

On a systems-level, we can also see that the structure itself is unsustainable. You may have seen news coverage in your own city about shelters reaching capacity and people not having anywhere to go. Research by Jadidzadeh and Kneebone (2018) shows that there is a noticeable increase in shelter users who are experiencing chronic homelessness, which is concerning because it will strain the ability of the shelter system to provide crisis relief and is an indication of a social order in trouble. In this next video, which is brief but succinct, Dr. Jacqueline Kennelly explains that our system has it backwards.

In this video, Dr. Jacqueline Kennelly argues that our system is designed as an emergency crisis response, and that a young person has to be in crisis before they can begin accessing services that allow them to get back into housing. She notes that this is backwards, as the more entrenched a young person becomes in homelessness, the harder it is to get back out. This video is 0:25 in length and has closed captions available in English.

Key Takeaways – Dr. Jacqueline Kennelly: Why does homelessness prevention matter?

If our current system is backwards and only helps people once they are already entrenched in homelessness, what could we do differently? Three researchers who speak in this section, Dr. Erin Dej, Dr. Stephen Gaetz, and Dr. Kaitlin Schwan, have argued that we can learn from countries that have shifted to address the prevention of homelessness, like Australia, Finland, and Wales (Dej, Gaetz, & Schwan, 2020). They have proposed a typology of homelessness prevention that is made up of the five interrelated elements of (i) structural prevention, (ii) systems prevention, (iii) early intervention, (iv) evictions prevention, and (v) housing stabilization.

Building on that typology, through systematically reviewing the literature, Oudshoorn, Dej, Parsons, and Gaetz (2020) add the additional sixth element of empowerment. The ultimate goal of their comprehensive framework is to support communities and governments in more effectively preventing homelessness through upstream approaches that address the root causes (Oudshoorn et al., 2020).

As you begin to learn and think about prevention, it may be useful to consider what our system looks like now, and what it could look like if it focused more on prevention and early intervention. This infographic and video from the Homeless Hub help to illustrate the central concepts.

Shifting towards the prevention of homelessness will require the commitment of public sectors across society. Consider, for instance, the experience of a person who is leaving a jail, hospital, or foster care placement without having somewhere to go. If done well, discharge planning can account for the needs of people as they exit these systems and ensure they receive adequate and appropriate follow-up care. However, as you will see throughout this book, there is often a disconnection between how public systems operate. Many of our public systems do not think about homelessness as being their concern. Dr. Nick Falvo discusses this issue and why prevention matters within this context, in the following video.

In this video, Dr. Nick Falvo identifies prevention as something that has garnered more attention within the past 5 years, in large part due to the work of Professor Stephen Gaetz and the Canadian Observatory on Homelessness. Dr. Falvo explains that it is important to talk about homelessness prevention because when we do, we identify institutions that contribute to the problem and hold them accountable. As an example, Dr. Falvo discusses the corrections system and how inmates are frequently released into homelessness without prior consideration or discussion about their housing status. Additional examples of institutions that discharge into homelessness include hospitals and the child welfare system. Dr. Falvo concludes that talking about prevention forces us to shine a light on institutions that contribute to the problem. This video is 2:35 in length and has closed captions available in English.

Key Takeaways -Dr. Nick Falvo: Why does prevention matter?

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/homelessness/?p=558#h5p-33

The shift towards prevention is markedly different than the current emergency-based system that we are used to. As you learn about this approach, it is useful to keep in mind the question raised by many researchers in this section, about why we make people wait until they are entrenched in homelessness before our system steps in to help them. Dr. Stephen Gaetz has written extensively about our current systems approach and the need to shift towards prevention. In the next video, he shares his thoughts.

In this video, Dr. Stephen Gaetz explains that exposure to homelessness for any length of time has profound and long-lasting effects on physical and mental health and increases the risk of victimization. He notes that by letting people fall into homelessness and not helping them exit immediately, we are contributing to the number and severity of issues they will experience. Dr. Gaetz argues that a “new orthodoxy” has existed for the past 20 years – combining Housing First, community strategies to coordinate efforts, and prioritization of chronically homeless people who have complex mental health and addictions issues. While he notes this bundle of activities is important, he argues that we need to do more to ensure people do not have to wait for housing and supports, because it contradicts Canada’s commitment to the right to housing. Dr. Gaetz notes that people are often reluctant to consider new ways of doing things, but that focusing on prevention would have benefits for individuals, families, and communities. He argues that the problems that create homelessness can be solved if we are willing to think about the issues in a different way, to intervene early, and turn off the inflows. In concluding his response, Dr. Gaetz offers a hypothetical comparison to the COVID-19 outbreak to demonstrate the harm that can be caused if we do not focus on prevention. This video is 6:46 in length and has closed captions available in English.

Key Takeaways – Dr. Stephen Gaetz: Why does homelessness prevention matter?

At this moment we encourage you to pause and read the framework for homelessness prevention developed by Dr. Gaetz and Dr. Dej. It is also noteworthy here that youth homelessness prevention is also critical and has its own framework document (Gaetz, Schwan, Redman, French, & Dej, 2018), which is discussed in depth in the chapter on Child & Youth Studies.

Gaetz, S. & Dej, E. (2017). A new direction: A framework for homelessness prevention [summary]. Toronto: Canadian Observatory on Homelessness Press.

Gaetz, S. & Dej, E. (2017). A new direction: A framework for homelessness prevention [summary]. Toronto: Canadian Observatory on Homelessness Press.

Gaetz and Dej (2017) write that prevention not only makes sense but is standard practice in many areas of society, such as vaccinating to prevent disease or wearing a seatbelt to prevent collision fatalities. Yet, despite its benefits, the impact of prevention can be difficult to measure. How can we prove that someone would have become homeless but did not because of our efforts? This is an issue that Dr. Erin Dej and Dr. John Ecker discuss in the next two videos.

In this video, Dr. Erin Dej explains that prevention matters because it is easier to stop something from happening than to try and fix it afterwards. She argues that prevention makes logical sense and draws parallels in the fields of health care, such as smoking cessation programs to prevent cancer and seatbelts to prevent car accident deaths. Dr. Dej notes that homelessness can be trauma-inducing and we need to think about how to apply the same logic of prevention to intervene before it starts. She concludes that the challenge with prevention is that it is difficult to show something did not happen, and therefore justify it in a budget, but that it is a hurdle we must overcome. This video is 3:18 in length and has closed captions available in English.

Key Takeaways – Dr. Erin Dej: Why does prevention matter?

In this video, Dr. John Ecker argues that if we had stronger homelessness prevention strategies, we would not have the level of homelessness currently seen in Canada. He draws comparisons with Finland and Norway to demonstrate how their stronger social safety nets result in lower levels of homelessness. Dr. Ecker notes that prevention is important because it focuses on the structural and systemic causes of homelessness, such as the need for more affordable housing and increases to income support rates. He identifies institutions, such as hospitals and jails, as having a key role and responsibility to prevent discharge into homelessness, which could be accomplished through legislation. Dr. Ecker notes that prevention allows us to identify risk and address it earlier, through a focus on structures and policies. He concludes that, while prevention efforts are sometimes critiqued for not having measurable outcomes, it is important to remember that what we do now will have an impact on future levels of homelessness. This video is 4:18 in length and has closed captions available in English.

Key Takeaways – Dr. John Ecker: Why does homelessness prevention matter?

One hurdle that researchers have identified with prevention is that it is difficult to measure something that does not happen, which makes it challenging to advocate for funding. If your job was to get funding for homelessness prevention efforts, what would you say to make this argument?

One hurdle that researchers have identified with prevention is that it is difficult to measure something that does not happen, which makes it challenging to advocate for funding. If your job was to get funding for homelessness prevention efforts, what would you say to make this argument?

One argument that can be made, is that ending people’s homelessness costs far less than our current emergency-based response. Consider this video discussion with Dr. Tim Aubry and the infographic that follows from the Canadian Observatory on Homelessness.

In this video, Dr. Tim Aubry argues that we are coming to a greater realization that we need to not only address homelessness but also think more broadly about prevention. He explains that homelessness is an awful experience and if we can prevent it, we will save people from going through trauma and a life crisis. Dr. Aubry concludes that from a service and policy standpoint, it is cost-effective and logical to prevent people from having to navigate the complicated system of emergency and crisis supports needed to get back into housing after homelessness has occurred. This video is 2:08 in length and has closed captions available in English.

Key Takeaways – Dr. Tim Aubry: Why does homelessness prevention matter?

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/homelessness/?p=558#h5p-34

At this point you may be thinking to yourself, “Okay, prevention sounds good and would save money, but let’s get real. We can never stop every person from becoming homeless!” If you are thinking this, you are absolutely right. Discussions around prevention always raise the concern that homelessness can never be completely avoided in every circumstance.

It may be useful to consider a parallel example of defining an end to homelessness. Turner, Albanese, and Pakeman (2017) explain that in a “functional zero” end to homelessness the goal is to achieve a point where there are enough services and supports to rapidly rehouse people and move them out of the homelessness system. In much the same way, while we may not be able to prevent every person from becoming homeless, we can prevent instances where possible and intervene early where prevention is not possible.

What we need in order to achieve a system where people are prevented from becoming homeless, or moved quickly back into housing, is a change in our thinking. We conclude this section with the optimistic words of Dr. Jeannette Waegemakers Schiff, as she shares her ideas for redesigning society for the collective good.

In this video, Dr. Jeannette Waegemakers Schiff argues that homelessness is first and foremost an issue of not having housing and that we can cut problems in half by keeping people housed. She notes that we are going to continue to perpetuate homelessness until we have government support at a federal and provincial level that provides an adequate supply of social housing. Dr. Waegemakers Schiff shares her wishful thinking ideal system, which includes systemic case management that provides instrumental support for people who are living precarious lives and may be experiencing one or more disabling condition. She concludes that we need to offer people more support, which is a larger political issue of governments recognizing that action needs to be taken for the common good. This video is 2:45 in length and has closed captions available in English.

Key Takeaways – Dr. Jeannette Waegemakers Schiff: Redesigning society for the collective good