Safe Sport: Critical issues and practices

Julie Stevens, Editor

Centre for Sport Capacity, Brock University

St. Catharines, Ontario, Canada

Safe Sport: Critical issues and practices by Julie Stevens is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

1

Safe Sport: Critical issues and practices by Julie Stevens (Editor) is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Vectors used in cover design and Figure 5.1 are derived from the Vecteezy.com free license. Unless otherwise noted, photos are used through Creative Commons licenses from Pixabay, Unsplash, Wikimedia, and Flickr. Unless otherwise noted, all figures should be credited to the chapter author and the editor.

![]()

Stevens, J. (Ed.) 2022. Safe Sport: Critical issues and practices. Ecampus Ontario. https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/safesport Licensed under CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0.

If you adopt this book as a required or supplemental reading in a course or other educational forum, please let us know by emailing the Editor, Julie Stevens, PhD, at jstevens@brocku.ca

2

This edited book is dedicated to all who enjoy participating in sport, no matter what the level or form. We hope our contribution builds upon the Red Deer Declaration, as well as the efforts of many others who place safety, inclusion, and diversity as a fundamental principle in their efforts to make sport better.

We, the Federal, Provincial, and Territorial Ministers responsible for Sport, Physical Activity, and Recreation recognize that all Canadians have the right to participate in sport—in an environment that is safe, welcoming, inclusive, ethical and respectful. An environment that protects the dignity, rights and health of all participants.

Red Deer Declaration for the Prevention of Harassment, Abuse and Discrimination in Sport, Conference of Federal-Provincial-Territorial Ministers Responsible for Sport, Physical Activity and Recreation, February 2019.

3

This edited book’s format is compliant with the Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act, 2005 (AODA). The tools used to build this safe sport edited book are structured to ensure that our content reflects the POUR principle, meaning that the resource is Perceivable, Operable, Understandable, and Robust. The Universal Design for Learning (UDL) framework used in the creation of this edited book gives students multiple ways to engage with content and demonstrate their knowledge by providing interactive content, audio recorder/written response opportunities, and videos.

To achieve AODA compliance we spoke with colleagues in the Centre for Pedagogical Innovation at Brock University and attended workshops including “Making Accessible Content with Pressbooks”, funded in part by eCampusOntario. We also conducted accessibility tests using the NonVisual Desktop Access (NVDA) screen reader in the Chrome browser.

Pressbooks is designed to be accessible for users of all abilities and compatible with screen readers and other assistive technologies. We opted to pursue accessibility over aesthetics in many cases. For example, while formatting a page using the table function may result in a nicer layout, it would not be accessible for an individual using a screen reader. Here are some of the main items we focused on to ensure this edited reader is accessible.

Should this resource require accessibility updates or corrections, please let us know by emailing the Editor, Julie Stevens, PhD, at jstevens@brocku.ca.

4

5

Julie Stevens, PhD, is an Associate Professor in the Department of Sport Management and Director of the Centre for Sport Capacity at Brock University. She currently serves as the Special Advisor to the President – Canada Games, where she leads the academic partnership between Brock University and the 2022 Niagara Canada Summer Games. For the past 30 years, Julie has conducted diverse and transdisciplinary research, and employs various models of organizational development to analyze dynamics of change and organizational design within sport. Her scholarly work emphasizes various topics such as institutional development, large-scale change, innovation, governance, managerial logics and practices, player development models, and ethics. Julie is also a North American Society for Sport Management Research Fellow (2013) and a Brock University 2020 Outstanding Co-op Supervisor Recognition Award recipient.

Isabelle Cayer is the current Director of Sport Safety at the Coaching Association of Canada (CAC). Her mission is to create a safer and more inclusive sport system for everyone. A former competitive athlete and NCCP certified coach, she is a current Coach Developer, facilitator, presenter and volunteer on a community sport board, and when the opportunity presents, at domestic national and international events. She has worked at the national level of sport for over 20 years at various organizations including the CAC and Skate Canada, and her work has focused on coach education and training, policy development, mentorship, women in coaching & leadership programming, diversity and inclusion initiatives for coach training and partner engagement, and the professionalization of coaching in Canada.

Karri Dawson is the Senior Director of Quality Sport at the Canadian Centre for Ethics in Sport (CCES) and the Executive Director of the True Sport Foundation. Karri holds a Bachelor of Commerce in Sports Administration from Laurentian University and has more than 25 years of professional experience managing corporate sponsorship, philanthropic donations and community engagement programs in amateur sport at the national level. Karri leads a team that engages sport leaders and organizations that share a common belief about what good sport can do, and works with partners and funders to develop initiatives that advance values-based sport in Canada.

Michele K. Donnelly, PhD, is an Assistant Professor of Sport Management at Brock University, specializing in areas of gender equality and sport. Michele also researches topics of alternative sport, girls and women-only activities in the sport realm, and research ethics. She is the co-founder and serves on the advisory board of the Girls on Track Foundation, whose mission is to help young girls build important life skills through participation in roller derby.

Peter Donnelly, PhD, has recently retired as a Professor and Director of the Centre for Sport Policy Studies at the University of Toronto. He has edited two major sociology of sport journals (Sociology of Sport Journal; International Review for the Sociology of Sport), and served as President of the North American Society for the Sociology of Sport, and General Secretary of the International Sociology of Sport Association. He began researching the maltreatment of athletes when he taught at McMaster University in the 1980s, and has continued that strand of research (among many others) by focusing in particular on the maltreatment of child athletes.

Hilary Findlay, LLB PhD, is a recently retired Associate Professor of Sport Management at Brock who specializes in risk management, regulatory issues, contracts and other legal issues affecting sport and recreation organization.

Susan L. Forbes, PhD, is the Manager of the Teaching and Learning Centre, as well as an Adjunct Professor in the Faculty of Health Sciences at Ontario Tech University in Oshawa, Ontario. Her research focuses on sports officials’ recruitment, development, retention, and attrition. She and her research partners recently published the book entitled Sports Officiating: Recruitment, Development and Retention (Routledge, 2020).

Gretchen Kerr, PhD, is a full Professor and Dean, Faculty of Kinesiology and Physical Education at the University of Toronto. She has spent her academic career devoted to promoting safe and equitable sport opportunities for all through research and knowledge transfer and exchange. As a co-Director of E-Alliance, the Canadian Gender Equity in Sport Research Hub, Gretchen is engaged in establishing a broad network of researchers and partnerships across the country to advance gender equity in sport. Gretchen was the senior author of Canada’s first national prevalence study of maltreatment among current and former national team members, and the subject matter expert for the development of the Universal Code of Conduct to Prevent and Address Maltreatment (UCCMS), and a contributor to Safe Sport education.

Bruce Kidd, PhD, is the Ombudsperson at the University of Toronto. He is a Professor Emeritus in the Faculty of Kinesiology and Physical Education, and the founding Dean of that faculty. He also served as Warden of Hart House, Principal of the University of Toronto Scarborough and Director of Canadian Studies, all at U of T. Bruce’s scholarship focuses upon the history and political economy of Canadian and Olympic sport. He has been involved in the Olympic Movement as an athlete (1964), journalist (1976), contributor to the arts and culture programs (1976 and 1988) and accredited social scientist (1988 and 2000). He was founding chair of the Olympic Academy of Canada (1983-1993), served on the board for Toronto’s 1996 and 2008 Olympic bids and is an honorary member of the Canadian Olympic Committee. Bruce has been a lifelong advocate of human rights and athletes’ rights.

Kasey Liboiron is the Manager of Sport Community Engagement at the Canadian Centre for Ethics in Sport (CCES). In this role, she manages the outreach and engagement of True Sport. The True Sport Principles define Canada’s commitment to values-based sport and are activated and supported by Canadian communities, sport organizations, schools, groups and individuals who believe in the difference good sport can make. Previously, Kasey worked as a secondary school Physical and Health Educator – particularly passionate about inspiring a commitment to physical activity and wellness. Kasey holds Bachelors of Education, Science, and Physical and Health Education from Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario.

Lori A. Livingston, PhD, is the Provost and Vice-President, Academic and Full Professor in the Faculty of Health Sciences at Ontario Tech University. She has participated as an athlete, coach, official, and administrator at the provincial, national, and international levels in the sport of women’s field lacrosse. She continues to contribute to sport through her research, including work in the area of sport officiating.

Ellen MacPherson completed her PhD in the Faculty of Kinesiology and Physical Education at the University of Toronto. Her research focuses on social behaviour in sport and online contexts, as well as athlete welfare and development. Ellen has been recognized internationally by the Association for Applied Sport Psychology (AASP) with the Sport Psychologist’s Young Researcher Award and her work has received funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC). As the former Director, Safe Sport at Gymnastics Canada, she led the development and implementation of an organizational Safe Sport Framework and the corresponding policy, education, and advocacy initiatives. In her current role at the University of Toronto, she conducts research and works with sport organizations to mobilize knowledge into practice with the ultimate goal of safe, developmentally appropriate, and equitable sport for all.

Leela MadhavaRau has served as the inaugural leader of equity, diversity and human rights initiatives at three different universities in both Canada and the United States, mostly recently as the Executive Director of Human Rights and Equity at Brock University. Leela’s expertise in the areas of equity, diversity and inclusion has provided her with the opportunity to present at many national and international conferences, as well as becoming a mentor for individuals beginning their careers in this field.

Marcus Mazzucco, JD, is Legal Counsel for the Ontario Ministry of Health and a Sessional Lecturer of Sports Law at the University of Toronto, Faculty of Kinesiology and Physical Education. Marcus has a Bachelor of Physical and Health Education from the University of Toronto and a Juris Doctor from the University of Victoria, British Columbia. The opinions and views expressed in this chapter are solely those of the author and do not represent the opinions or views of the Ontario Government.

Ian Moss is the CEO of Gymnastics Canada, and has been involved with the organization since 2017. Ian’s involvement in national sport organizations reaches beyond gymnastics, and throughout his career he has worked with seven different NSOs and two MSOs, forming a well-rounded knowledge of Canadian and international sport at both the technical and management level. A seasoned sport association leader with over twenty years of national and international experience, Ian has built a strong vision and operating capacity to translate “big picture” needs into clear operating principles and partnerships.

Peter Niedre is the Director of Education Partnerships at the Coaching Association of Canada (CAC), and oversees the National Coaching Certification Program (NCCP). This role involves working with over 65 National Sport Organizations, 13 Provincial and Territorial Coach representatives and other Canadian Sport System Partners in development and delivery of the NCCP. Prior to the CAC, he worked at Canoe Kayak Canada as the National Junior coach, and Director of Coach and Athlete Development. Prior to that, he was a physical education and outdoor education teacher at the secondary level for 10 years, and part-time lecturer at University of Ottawa in the School of Human Kinetics. Peter is also a Master Coach Developer in sprint Canoe Kayak and in multisport delivery with the Coaches Association of Ontario and actively volunteers at the community level coaching cross country skiing and biathlon.

Talia Ritondo, MA, is a recent Master’s graduate of Brock’s Recreation and Leisure program, where she studied how postnatal women are affected by gendered expectations of motherhood while returning to team sport. She plans to pursue a PhD in the future, with a focus on bringing an intersectional social justice lens to the sport research field. She currently serves as Brock Human Rights and Equity’s Gender and Sexual Violence Education Coordinator, where she coordinates workshops, training and events that educate students, staff, and faculty about gender and sexual violence through an intersectional, anti-oppression lens. For leisure, they love to play volleyball, rock climb, watch Netflix, and play video games.

Kirsty Spence, PhD, has a 20-year background of researching leadership topics and more specifically, leaders’ vertical development and its relationship to leadership effectiveness and program development. She is passionate about Safe Sport topics, having completed Master’s-level research on an inter-organizational network analysis of the implementation of the Speak Out! Program within Hockey Canada in 2001. Dr. Spence has received the Professional Coaching Certification (P.C.C.) designation with the International Coaching Federation (ICF) as a certified Integral Master Coach™.

Georgina Truman, MHK, is the Manager, Athlete Relations and Operations at AthletesCAN. In her role, she is responsible for administration, programs and services, communications, athlete relations, and events. Her experiences as a multi-sport athlete in her youth translated into a passion for the sport industry and strong connection to athlete-centred sport. Prior to joining AthletesCAN, she developed experience in the recreation, university, and non-profit sport sectors in communications, marketing, and client relations. She holds a Master’s degree of human kinetics with specialization in sports management and Bachelor degree of human kinetics from the University of Ottawa.

Michael Van Bussel, PhD, has over 18 years of academic, administrative, and service experience in Sport Management. His educational background includes a PhD focusing on Sport Law and Policy Studies from Western University. He held faculty positions at Jacksonville University and Wilfrid Laurier University in the field of Sport Management. He has won awards in teaching and coaching and was named OUA (USPORT) Provincial Coach of the Year on two separate occasions with the Western University Women’s Soccer Program. His research interests include sport law, risk management, governance and policy, and coach/athlete communication.

Erin Willson, MSc, is currently a PhD candidate in the Faculty of Kinesiology and Physical Education at the University of Toronto. Her areas of research interest include maltreatment in sport, athlete empowerment and advocacy. Erin also sits on the Board of Directors at AthletesCAN. As a former Olympian, Erin brings a unique perspective to her research endeavors.

6

Four Brock University students reviewed sample chapters of this edited book in November 2021. We are grateful for the insight and comments of:

Brock University’s Centre for Pedagogical Innovation (CPI) provided assistance in the realm of grant writing, accessibility, technology-enabled learning, and general support of our instructional design methods. We are grateful for the services of:

7

Creating an open access online resource like this is beneficial because it offers high-quality scholarship and professionally researched materials for free to anyone who is interested in the topic of safe sport. Open access resources like Safe Sport: Critical issues and practices ensure a secure transfer of knowledge from trusted sources for learners and for organizations looking to educate their members and the general public, many of whom are working with limited resources. By making this resource open access, this critical information is available to a wider audience, many of whom might not have the funding or resources to acquire such a book.

This is achieved through Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act, 2005 (AODA) compliant design and coding, captioning and transcription of all video and audio components, and full written descriptions for all figures and diagrams. We have also provided links to external resources, news articles, videos and podcasts for learners to explore particular issues in depth. There is also an abridged French version of this book, showcasing select chapters for learners looking to read about safe sport in both official languages.

The tools used to build this safe sport edited book are structured to ensure that our content reflects the POUR principle, meaning that the resource is Perceivable, Operable, Understandable, and Robust. The Universal Design for Learning (UDL) framework used in the creation of this edited book provides multiple ways for learners to engage with content and demonstrate their knowledge. For example, chapters includes interactive content, audio recorder/written response opportunities, and videos. A student focus group review was conducted prior to publishing, and their feedback was incorporated into the pedagogical approaches taken towards the chapters.

This edited book is a unique resource that has the potential to benefit a wide range of students, educators and professionals.

It may be used by learners at a university or college across several disciplines such as sport management, kinesiology, physical education, recreation, law, sociology, history, social justice, gender studies, child and youth studies, and policy studies. It is this generation of students who represent the next generation of coaches, parents and sport organizers who must implement the necessary changes required to realize the safe sport goals outlined in this resource. As such, they need to have access to these critical research and training materials.

This edited book is a robust resource for researchers examining legal, social, ethical, and managerial issues in sport. It also targets professionals who work across public, nonprofit, and commercial sectors, as well as Canadian sport organizations at all levels who must lead programs and services where safe sport issues must be addressed. Finally, this book is useful to community and grassroots organizations as educational training materials for their members and volunteers.

The blocks of text in this edited book are split up with interactive figures and colourful text boxes designed to directly engage learners with the material. Instructors may utilize these text boxes, which contain relevant content and thought-provoking questions, for student assignments. These include the following:

In addition to text boxes, there are multiple chapter sections that are useful for both learners, educators and professionals. To ensure accessibility, we structured the chapters with proper heading hierarchies as well as colour coding and icons to facilitate simpler way-finding throughout the text.

8

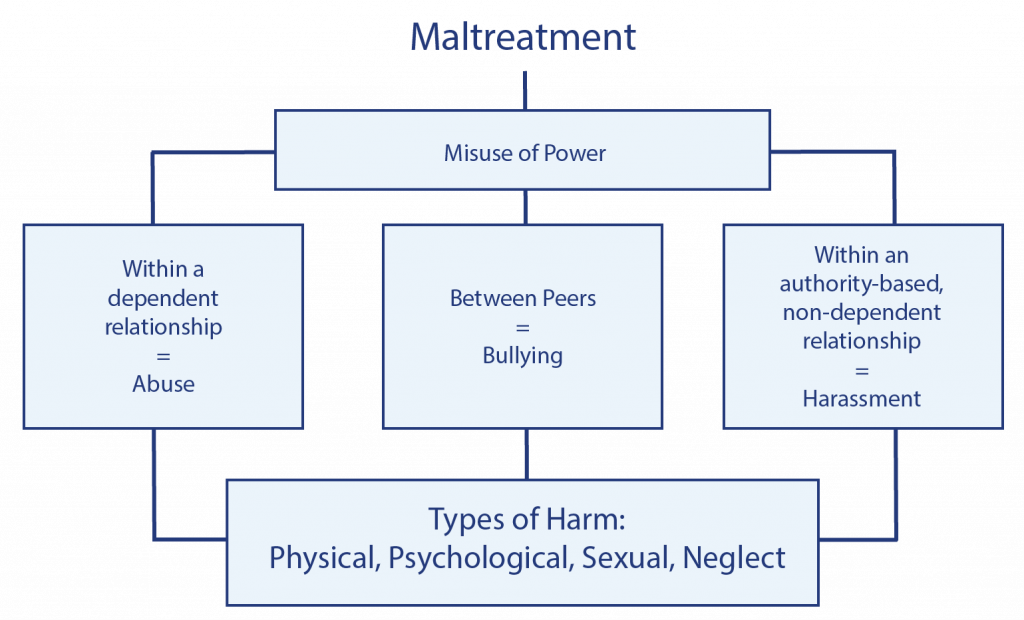

Figure 2.1 Differentiation Between Relationships and Terms Including Bullying, Abuse, and Harassment

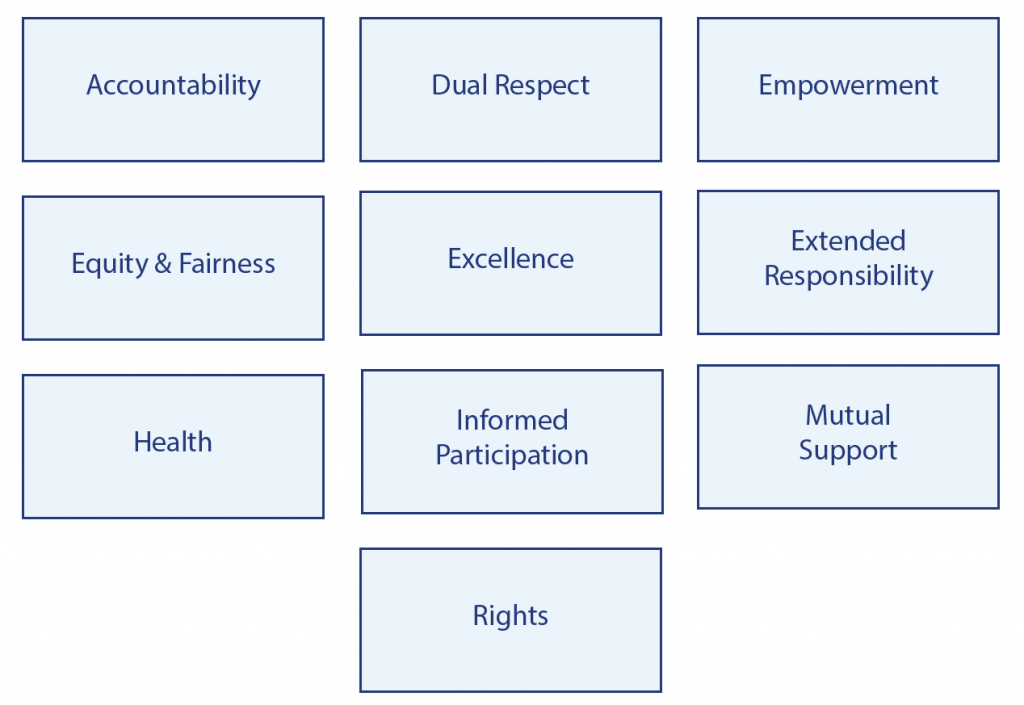

Figure 2.2 Characteristics of an Athlete-Centred System

Figure 4.1 Examples of “Troubling” Sport Organization Governance and Practices

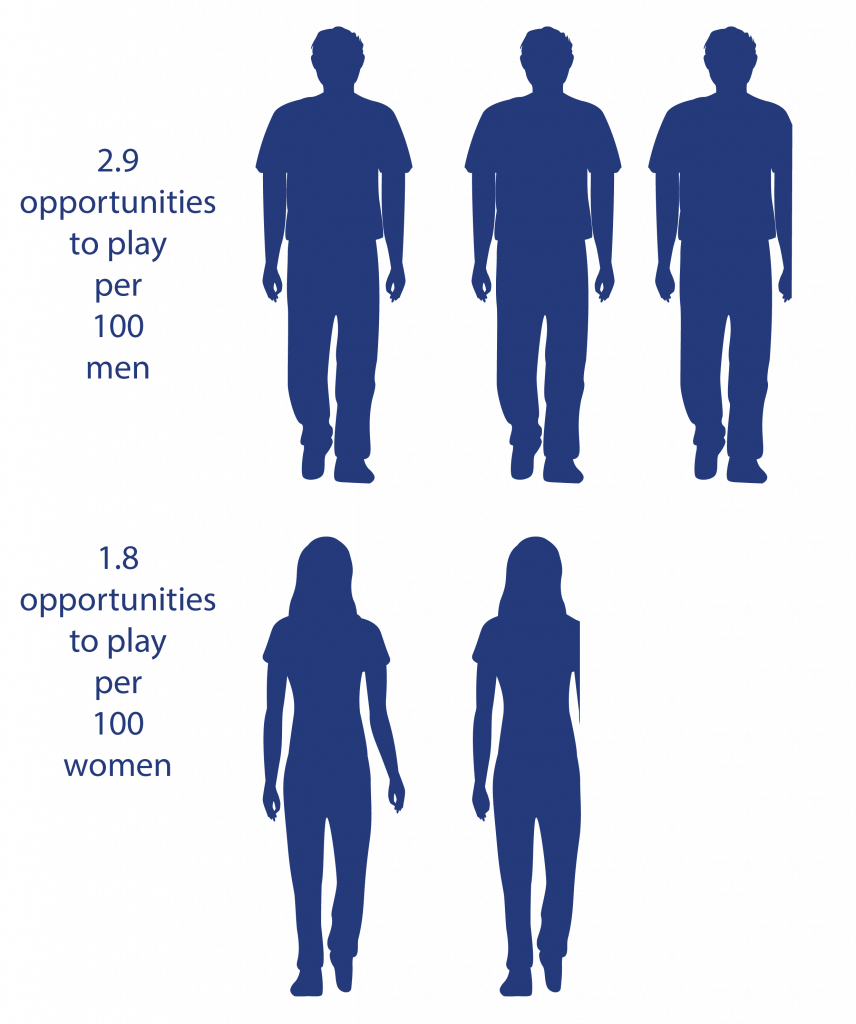

Figure 5.1 Opportunities to Play for University Men and Women

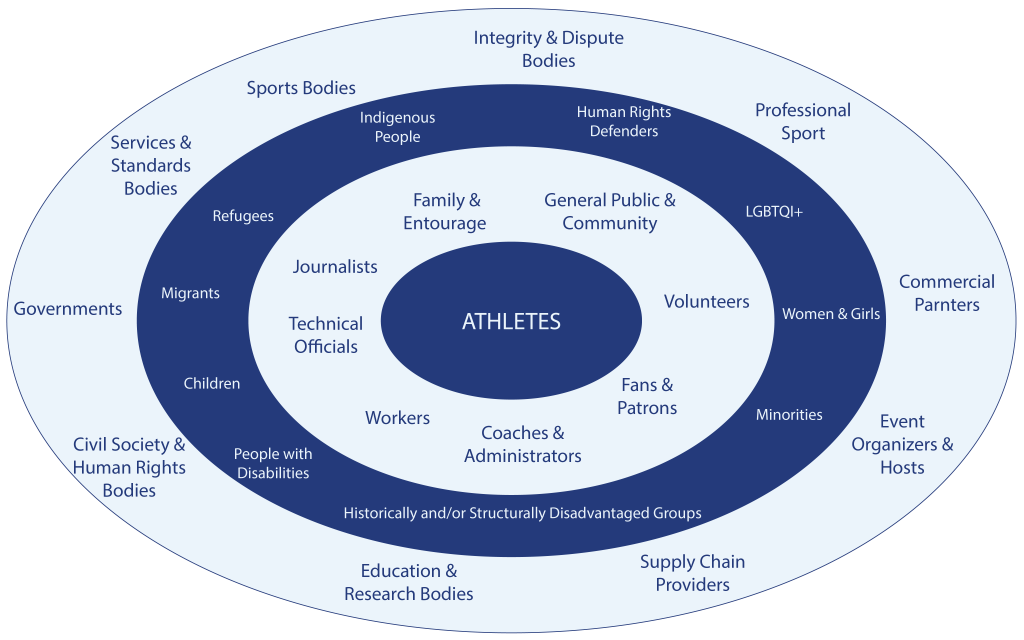

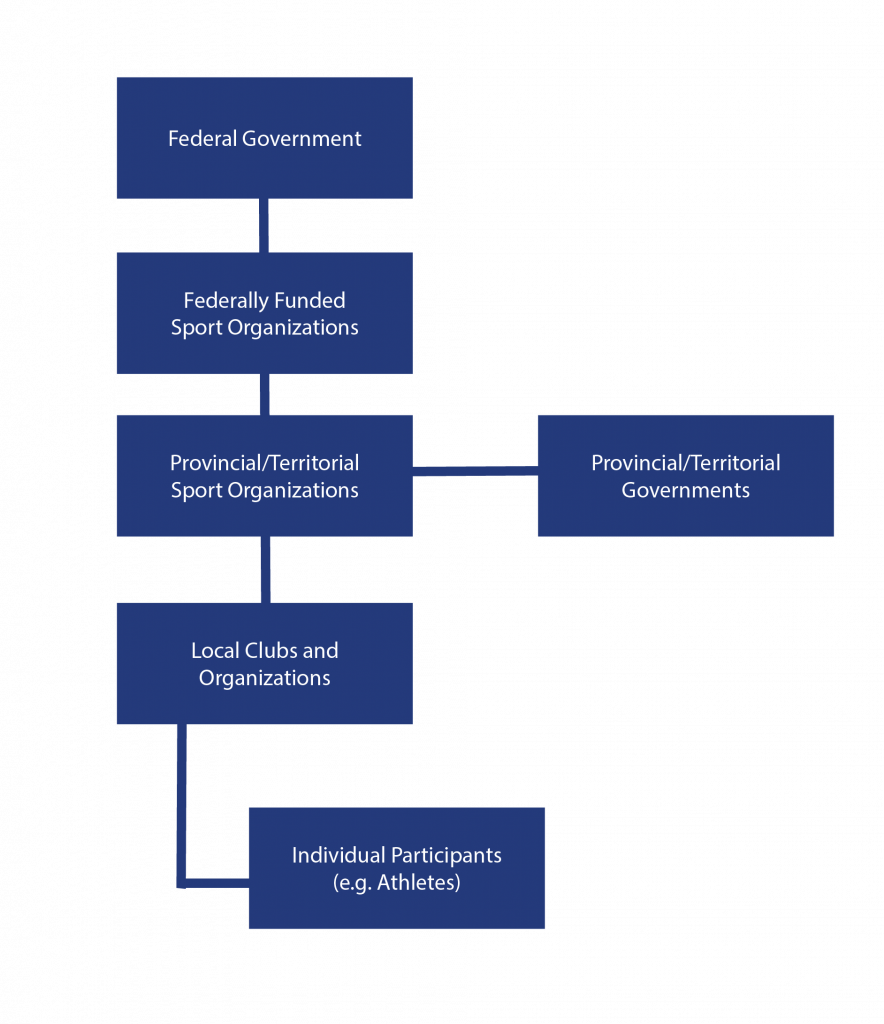

Figure 5.2 Sport Ecosystem

Figure 5.3 IDEA: Inclusion, Diversity, Equity, and Accessibility

Figure 5.4 Chapter Five Review

Figure 6.1 Legal Relationships Between SDRCC, Sport Organizations and Participants

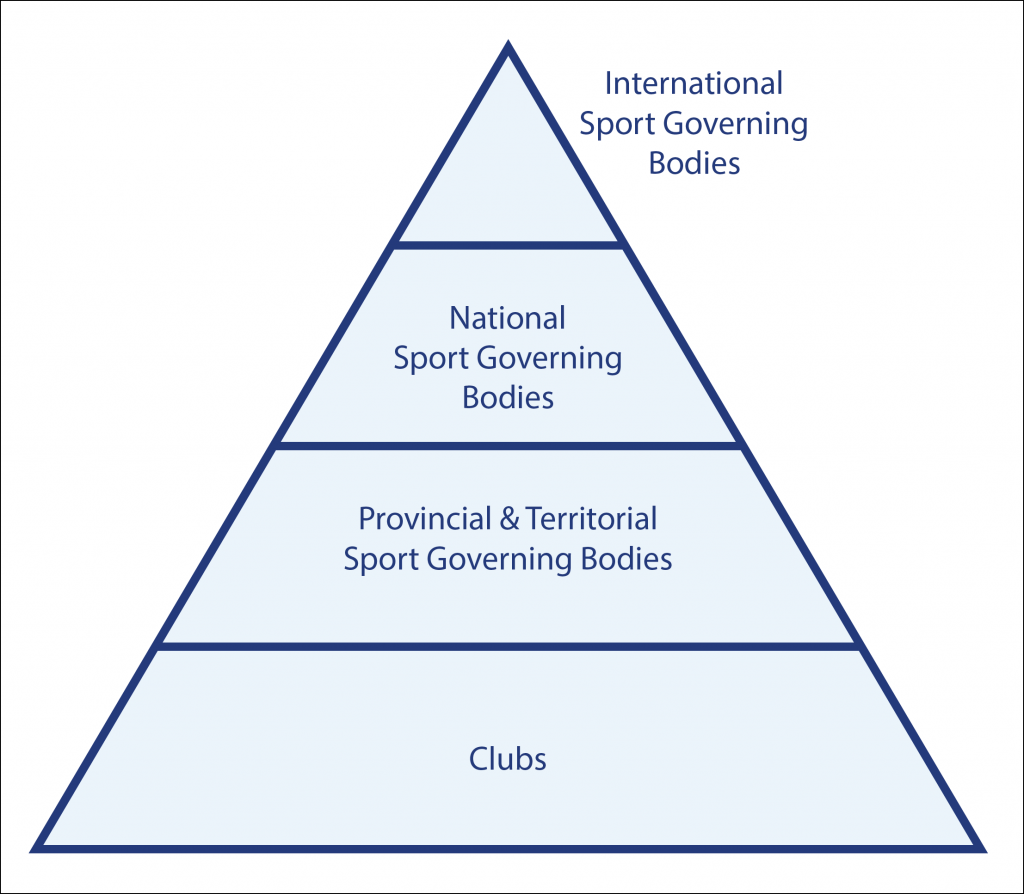

Figure 6.2 Pyramidal Structure of Sport Hierarchy

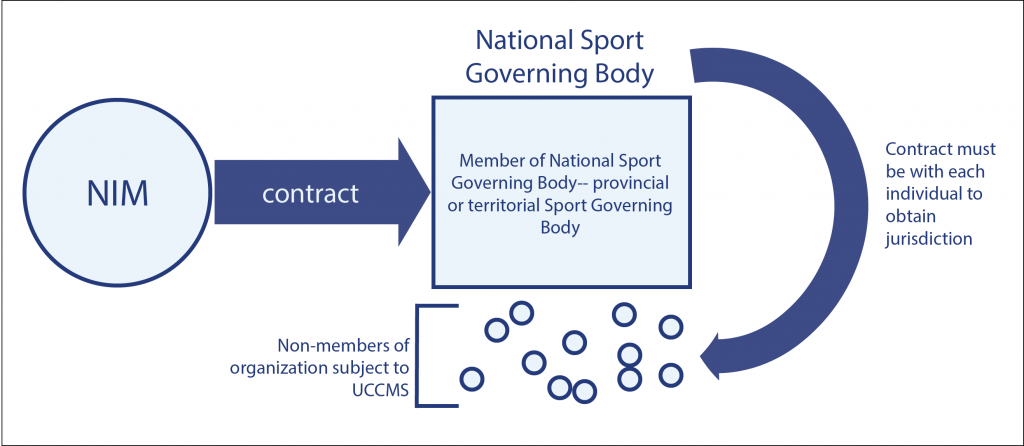

Figure 6.3 Contractual Options for Acquiring Jurisdiction at National Level

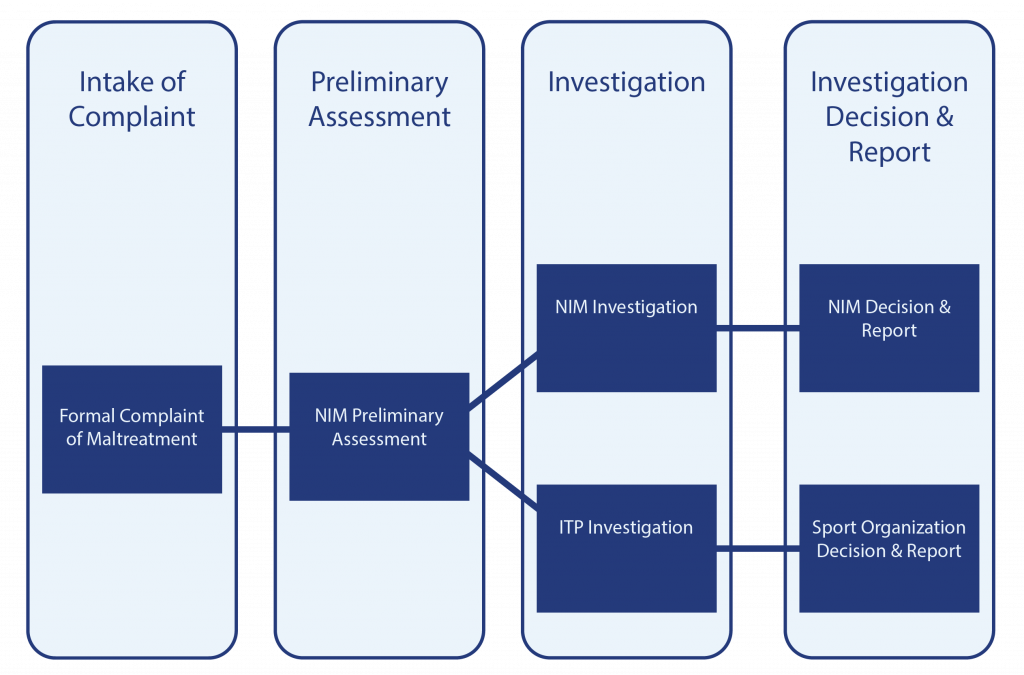

Figure 7.1 Pathway of a Complaint in the Investigative Phase

Figure 7.2 Types of Evidence Matching Exercise

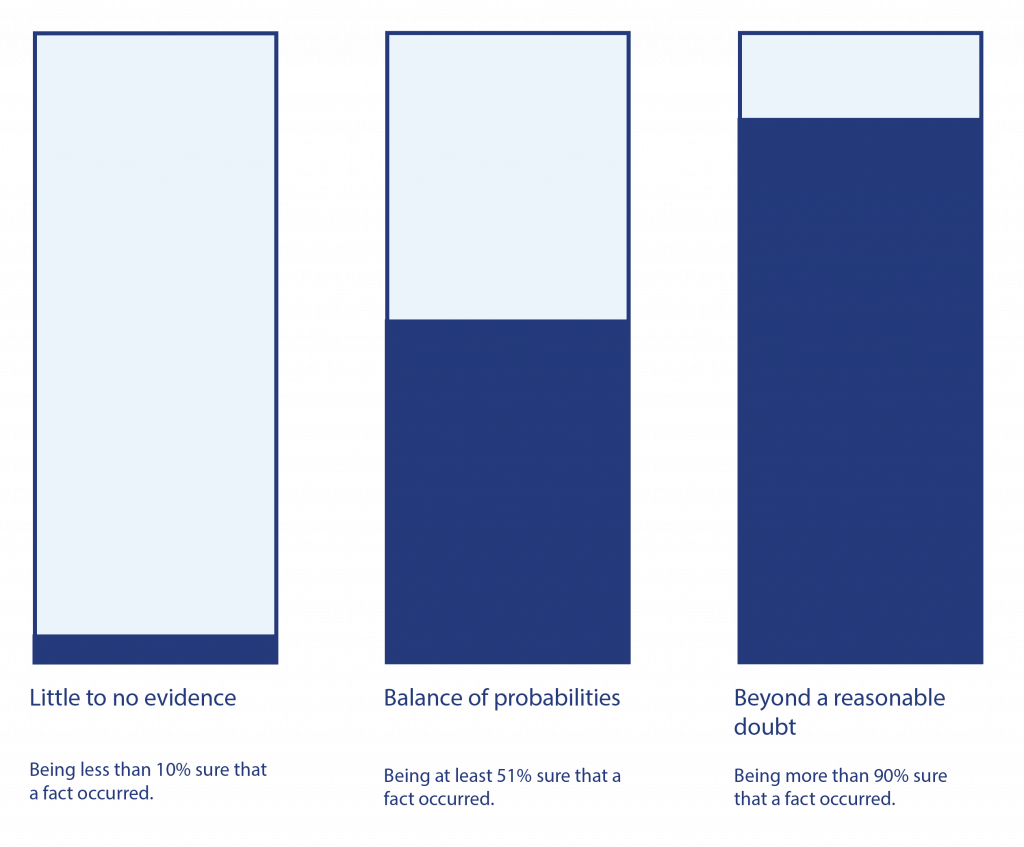

Figure 7.3 Standards of Proof Illustrated

Figure 8.1 Parties Involved in Dispute Resolution

Figure 8.2 SDRCC Tribunals

Figure 8.3 Hierarchy of Canadian Courts and Tribunals

Figure 8.4 Decision-Making Hierarchy in Sports System

Figure 9.1 Dispute Scenarios for Post-Investigation Decisions

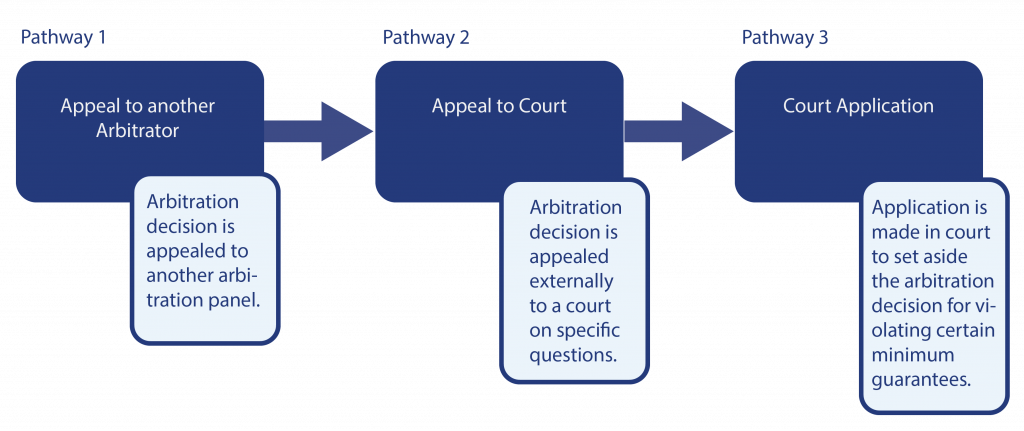

Figure 9.2 Scope of Review Options

Figure 9.3 Standards of Review and Deference to Original Decision-Makers

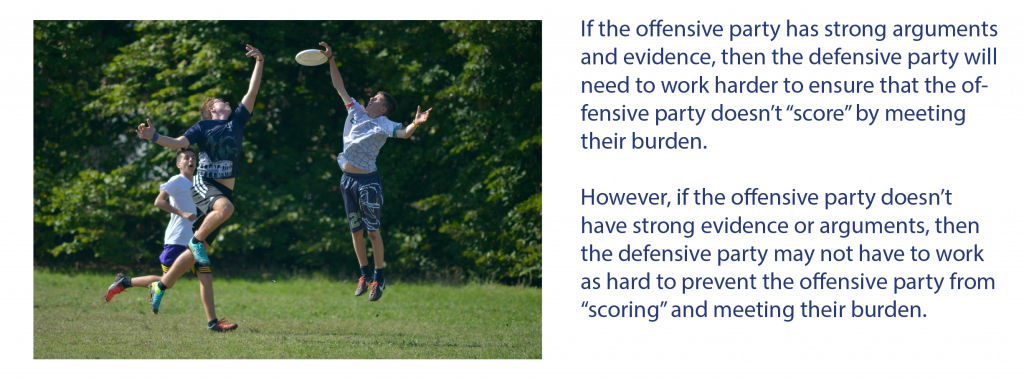

Figure 9.4 Burdens of Proof as a Sporting Analogy

Figure 9.5 Standards of Proof Illustrated

Figure 9.6 Ambiguities in Language

Figure 9.7 Principles Relevant to an Arbitrator’s Review of an Original Decision with UCCMS Interpretation

Figure 10.1 Pathways for Challenging a Sport Maltreatment Arbitration Decision

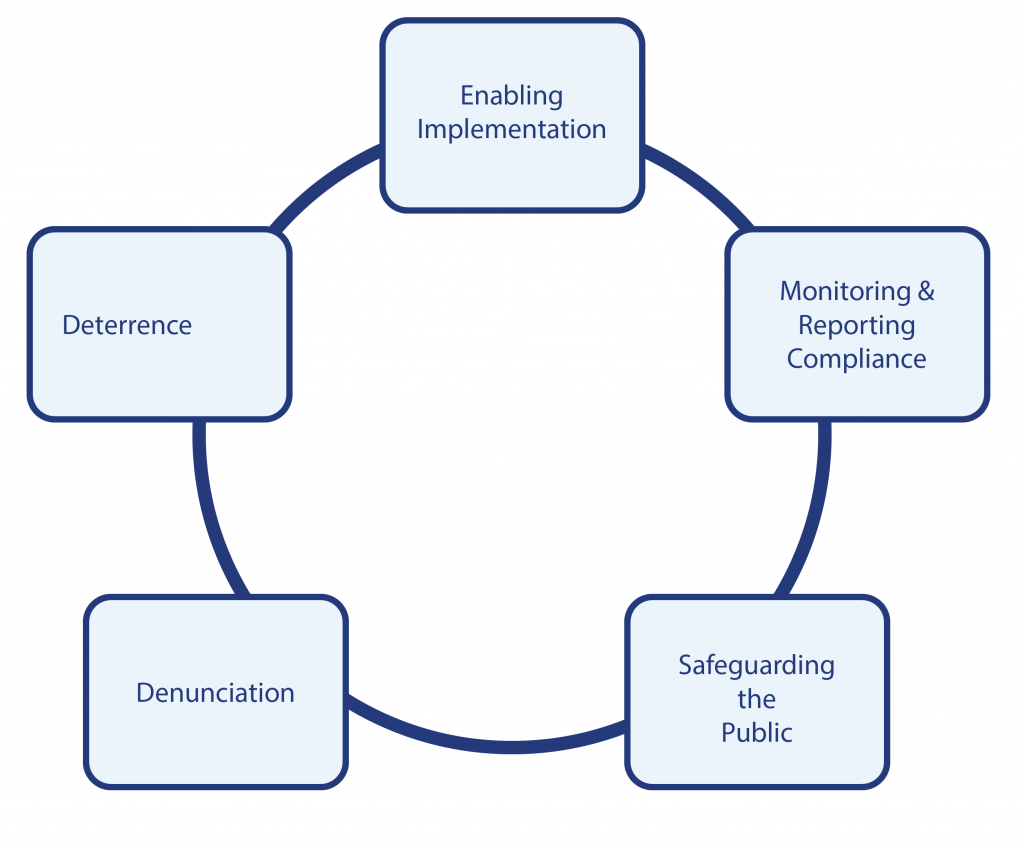

Figure 10.2 Objectives of Publicly Reporting Sanctions in the Sport Maltreatment Context

Figure 10.3 PIPEDA Information Principles

Figure 10.4 Contractual Relationships in Sport to Enforce Sanctions

Figure 11.1 True Sport Member Type Infographics

Figure 12.1 Disciplines of Gymnastics

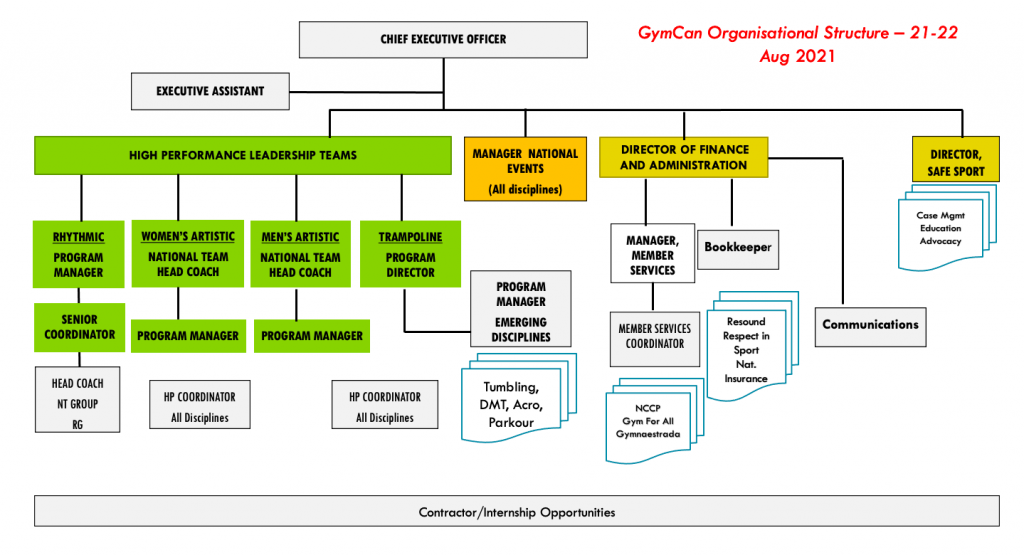

Figure 12.2 GymCan Organisational Structure

Figure 12.3 Gymnastics Canada Vision, Mission, Overarching Goals, and Values

Figure 12.4 Sample Skills and Responsibilities of a Safe Sport Portfolio Position

Figure 12.5 GymCan’s Six Key Steps to Developing the 2018 Safe Sport Framework

Figure 12.6 Phases of Safe Sport Policy Revitalization

Figure 13.1 Relational Risk Management Plan

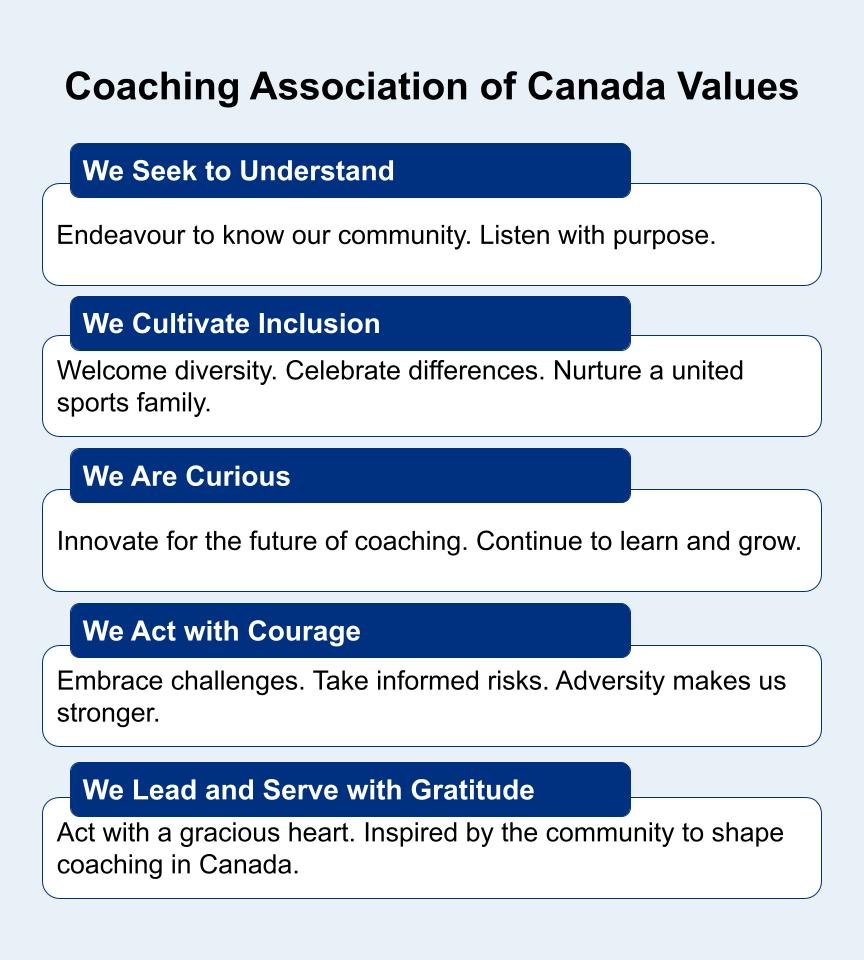

Figure 14.1 Coaching Association of Canada Values

Figure 14.2 Sport Coaching Research

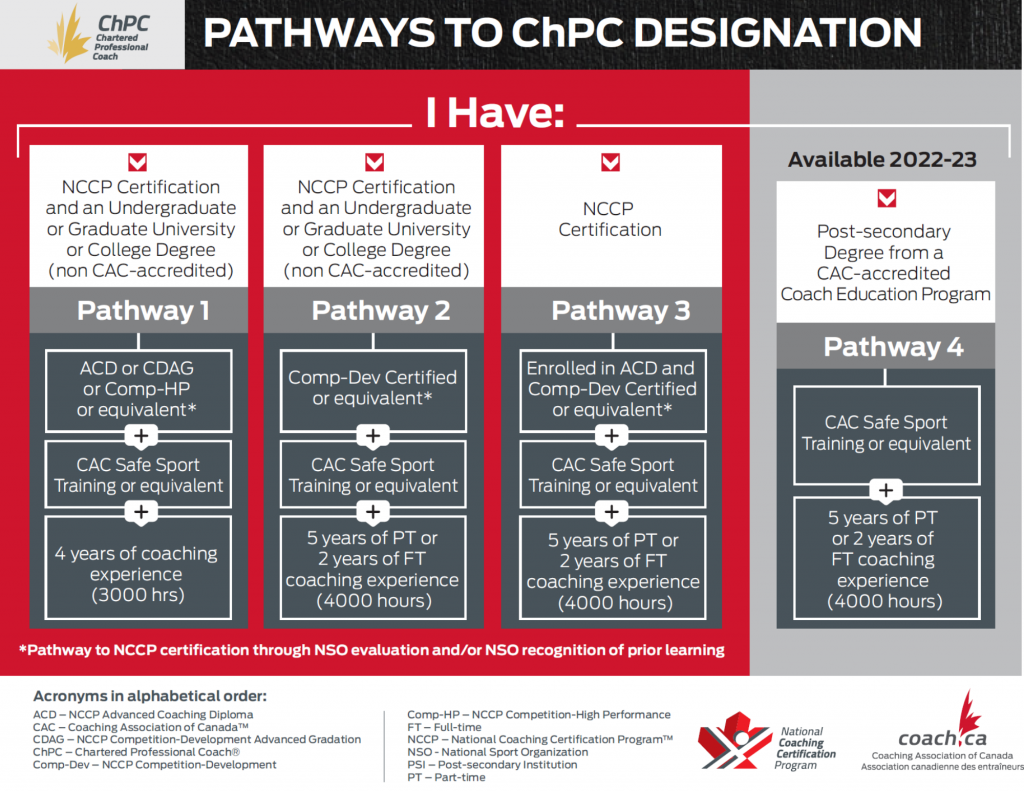

Figure 14.3 Pathways to Chartered Professional Coach (ChPC) Designation

Figure 14.4 A Socio-Ecological Model to Inform Safe Sport

Figure 14.5 Individuality and Lived Experiences of Participants

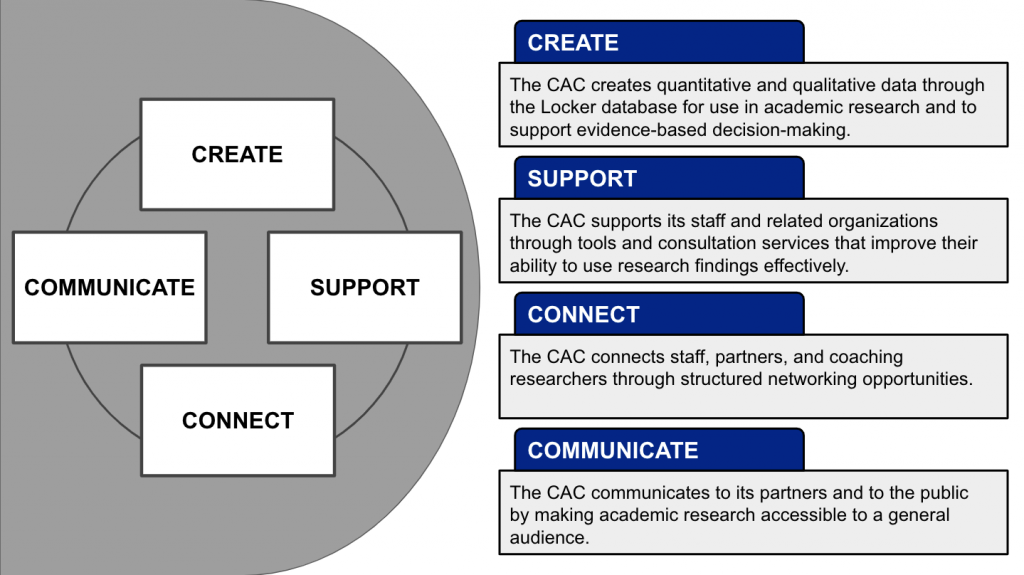

Figure 14.6 CAC’s Responsible Coaching Movement

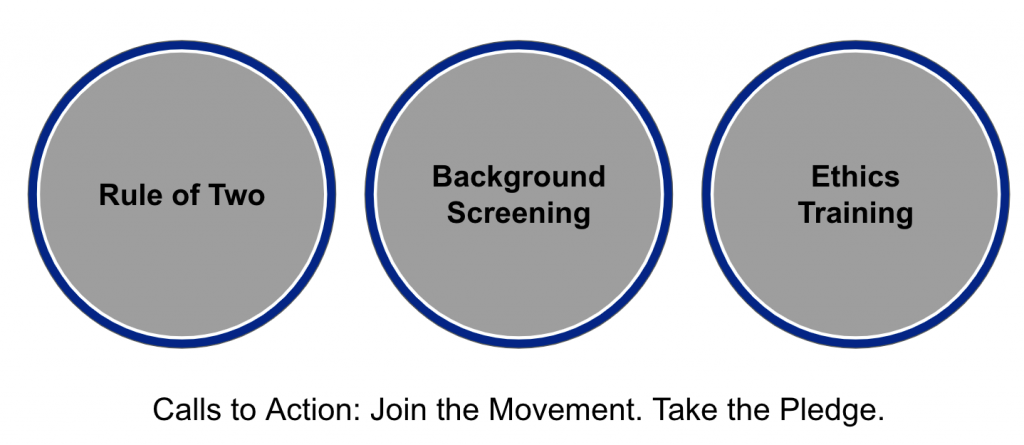

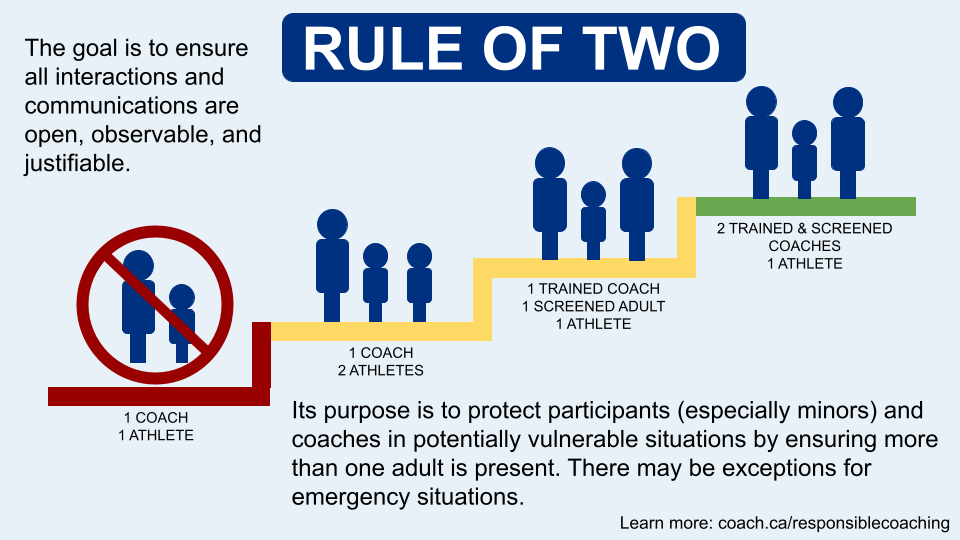

Figure 14.7 The Rule of Two

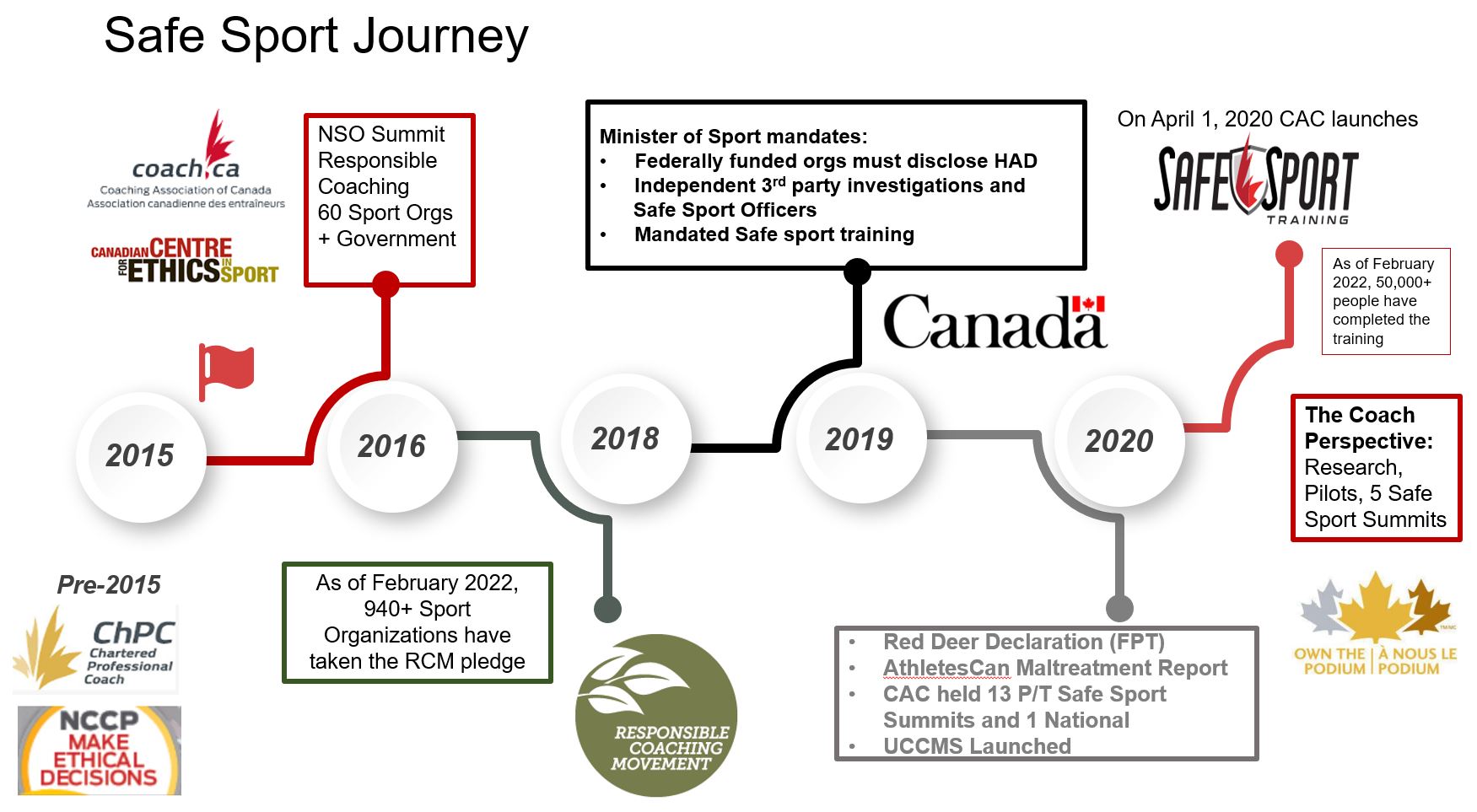

Figure 14.8 The CAC Safe Sport Journey 2015-2021

Figure 15.1 Rules Classification

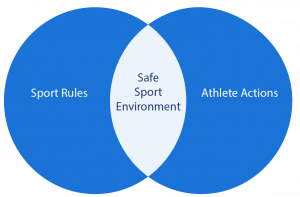

Figure 15.2 Safe Sport Environment

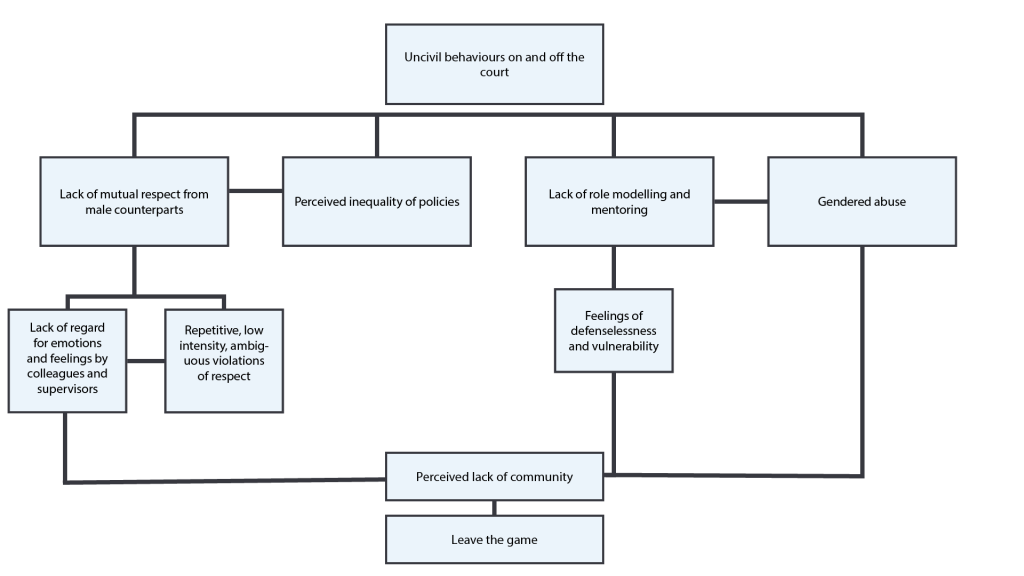

Figure 16.1 Why Female Basketball Referees Leave the Game

Figure 17.1 Reasons for not Reporting

Figure 17.2 Steps to Realize the UCCMS

9

Table 2.1 Maltreatment Types and Examples

Table 7.1 Overlap Between Definitions of Maltreatment under UCCMS and Canadian Criminal Laws

Table 7.2 Summary of Duty to Report under Provincial/Territorial (P/T) Child Welfare Legislation

Table 8.1 Safeguards for Ensuring Arbitrator Independence and Impartiality in Sport Maltreatment Cases

Table 9.1 International Comparison of Scope of Review and Procedural Rules

Table 9.2 Summary of CAS and SDRCC Confidentiality Rules

Table 9.3 Purposes of Disclosing Arbitration Decisions and Relevant Considerations

Table 9.4 Privacy Rules in Sport Maltreatment Arbitration Context

Table 10. 1 Grounds for Setting Aside an Arbitration Decision

Table 12.1 GymCan Key Objectives for Safe Sport Advocacy Initiatives

Table 17.1 Summary of Canadian Prevalence Study of National Team Member Maltreatment Experiences

10

Video 1.1 Julie Stevens: A Summary of the Athletes’ Voices Panel

Video 1.2 Julie Stevens: A Summary of the Governance and System Re-Engineering Panel

Video 2.1 Erin Willson: Body Image and Belittling Athletes

Video 2.2 Allison Forsyth: What is Complicity?

Video 2.3 Danielle Lappage: Attending the AthletesCAN Safe Sport Summit

Video 2.4 Camille Bérubé: An Athlete’s Perspective on Safe Sport

Video 2.5 Neville Wright: An Athlete’s Perspective on Racial Discrimination in Sport

Video 2.6 Erin Willson: The Definition of Safe Sport

Video 3.1 Bruce Kidd: Sport and the Struggle for Inclusion

Video 3.2 Bruce Kidd: The Fight for Gender Equity in Canadian Sport

Video 3.3 Bruce Kidd: The Long Struggle for Safe Sport

Video 4.1 National Sports Governance Observer: Play the Game

Video 4.2 Peter Donnelly: Athletes Rise

Video 11.1 A Recipe for Good Sport

Video 11.2 The Power of True Sport

Video 11.3 True Sport Lives Here Manitoba

Video 11.4 The Ride Home

Video 14.1 Safe Sport Training Promo, CAC

Video 14.2 Isabelle Cayer: Sport is in a Culture Renovation

Video 14.3 Isabelle Cayer: Support Through Sport Series

Video 17.1 Gretchen Kerr: Why Safe Sport Now?

Video 17.2 Gretchen Kerr: Athletes’ Fear of Repercussions

Video 17.3 Gretchen Kerr: Studying Athletes’ Willingness to Report Incidents

Video 17.4 Gretchen Kerr: The Duty to Report Concerns in Sport

11

You’ll notice throughout this edited book that in the beginning of every chapter, there is a list of Key Dates that pertain directly to its content. The Key Dates listed below provides a master compilation of important dates from each of the chapters in this book, showing the interconnectedness of important themes and historic moments in the movement towards safer sport.

Click the arrows and scroll through the list to learn more about where we currently stand in this journey, and how we came to be here.

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/safesport/?p=76#h5p-1

12

This project is made possible with funding by the Government of Ontario and through eCampusOntario’s support of the Virtual Learning Strategy. To learn more about the Virtual Learning Strategy visit https://vls.ecampusontario.ca

I

In Part 1, Julie Stevens, PhD, Professor of Sport Management at Brock University, briefly frames the safe sport edited book within current academic and professional contexts and explains the importance of understanding these selected contributions if safe sport progress is to be made in the Canadian sport system.

1

Julie Stevens

I am excited to share with you this book on safe sport. Comprised of 18 chapters from 21 contributors across academic and professional realms, the book offers current and insightful commentary that addresses athlete, governance, human rights, legal, coaching, and officiating issues.

The creation of this open education resource (OER) was driven by a compelling necessity to ensure safe sport experiences for all athletes within all contexts. The organizers of the 2021 Safe Sport Forum hosted by the Centre for Sport Capacity at Brock University took this athlete-focused approach seriously. During our planning and staging activities, we were unified around two key priorities: First – that athletes be at the forefront of the discussion and second – that the discussion would continue beyond the Forum!

The first priority manifested in the Forum name – Athletes First: The Promotion of Safe Sport in Canada, an athlete panel to launch the program, and the positioning of athletes as the central beacon for shared discussion among attendees. The sessions applied various perspectives to address the harassment and abuse of athletes, and the lack of administrative action in these instances which have been highlighted in recent cases in the media and the courts. Most importantly, the Forum acknowledged that the long-term negative ramifications of a failure to ensure safe sport for athletes at all levels of the Canadian sport system is a significant issue that requires discussion and action.

As someone who has held several roles in sport, including scholar, volunteer, coach, official, parent, advocate and most importantly, athlete, I have tried to cultivate a safe and respectful environment when I engage with others through sport. Finding a way to keep this focus at the forefront was a personal endeavour. But during a recent strategic planning session I attended, I learned about a perspective that Jeff Bezos has implemented in Amazon for a very long time – aptly described as the “One Empty Chair Rule.”Anders, G., 2012. The rule ensures that an empty chair is placed at the table in order to make certain the customer is top-of-mind at every company meeting.Koetsier, J., 2018. Bezos refers to his mantra as “customer obsession”.

The “Empty Chair” approach resonated with me and stirred thoughts about how it might guide safe sport innovation within the Canadian sport system. The lens made me think of ways a consistent positioning of the athlete – which in sport is the central stakeholder – at the forefront of decision-making might enhance safe sport. What if an empty chair is placed at the table at every meeting where sport leaders make decisions in order to ensure the athlete is top-of-mind?

Athlete-centredness is not new to the sport conversation. In the 2000s, criticism grew over the excessive bureaucracy, corporatization, and results-based orientation of the Canadian high- performance sport system. Calls for change, such as the introduction of athlete-centred initiatives have been made within the Canadian sport system.Thibault, L.& Babiak, K., 2005. The discussion has expanded into various areas of sport, such as anti-doping policy, and beyond the Canadian border to engage a global dialogueGrigaliūnaitė, I. & Eimontas, E., 2018. and competition at the international level.Ciomaga, B., Thibault, L., & Kihl, L., 2017. Further, arguments for a ‘deliberate democracy’ lens were raised as a concept that might counter power imbalance within the sport system and open the door for athletes to engage in decision-making.Kihl, L., Kikulis, L., & Thibault, L., 2008.

Extending upon the notion of power, the politics of athlete-centredness in a sport system has been examined in the context of performance enhancement drugs resulting in claims that anti-doping policy development fails to include athletes as policymakers.Jackson, G. & Ritchie, I., 2007. More recent work connects athlete input with sustainable elite sport in relation to coaching, holistic perspectives, and the co-creation of an athlete’s overall development.Dolsten, J., Barker-Ruchti, N. & Lindgren, EC., 2019. Interestingly, a review of athlete representation within the decision-making forum of major sport event properties has revealed that Paralympic athletes have a vote through the International Paralympic Committee Athlete Council, whereas the voting representation of Olympic Games and Commonwealth Games athletes is not as evident.MacIntosh, E. & Weckend Dill, A., 2015.

While these works demonstrate how athlete-centredness has been addressed over the past 20 years, the difference now is momentum – the sport community seems far more resolute about hearing from athletes with respect to their view of a safe sport experience.

Hence, this book about safe sport begins with the athlete voice!

In Part 2, Erin Willson and Georgina Truman (AthletesCAN) share powerful insight about the athlete experience in relation to safe sport. The research they address demonstrates the importance of gathering athlete voices, including voices at the lower levels of the sport system, expanding our individual awareness and building our collective awareness about safe sport. It is critical to communicate and implement safe sport policies in ways that align with the level of the athlete.

Video provided by Brock University Centre for Sport Capacity. Used with permission. [Transcript]

Part 3 includes three chapters that draw upon different perspectives to examine how athletes are positioned within a larger sport system. Bruce Kidd examines the historical struggle for safe sport within a system fraught with contested terrain. Peter Donnelly critiques the long-standing autonomy of sport and argues that reengineering the way sport organizations operate will increase safe sport accountability. Finally, Leela MadhavaRau and Talia Ritondo propose encompassing a human rights framework into the broader context of safe sport and discuss how safe sport can be achieved.

Video provided by Brock University Centre for Sport Capacity. Used with permission. [Transcript]

Part 4 provides an exceptionally comprehensive five-chapter account of safe sport legal considerations. Hilary Findlay and Marcus Mazzucco examine key legal issues that arise from the creation of an independent body to oversee the implementation of the Universal Code of Conduct to Prevent and Address Maltreatment in Sport (UCCMS) and ensure the fair, transparent and effective management of reported cases of maltreatment. They break down the role of the new independent body in relation to four phases – jurisdiction, investigation, dispute resolution and enforcement. Understanding the legal aspects of the UCCMS as it becomes a mandatory element of the federal sport system, and possibly provincial/territorial and local levels of sport, is critical for students, researchers, professionals and other stakeholders within the Canadian sport system.

Part 5 offers two “from-the-field” exemplars from sport organizations that have effectively developed safe sport policies and practices. Kasey Liboiron and Karri Dawson (True Sport) champion the True Sport values-based approach to sport as a fundamental foundation for the intentional integration of effective safe sport policy by stakeholders throughout the sport system. Ellen MacPherson and Ian Moss (Gymnastics Canada) offer an insider account of the initiatives Gymnastics Canada completed in order to develop, support and foster safe sport throughout the organization.

Part 6 shifts the focus to coaches where two chapters address the role a coach plays in a safe athlete experience. Michael Van Bussel and Kirsty Spence outline how a care-driven model and relational risk management plan offer a constructive guide for safe sport relationships among athletes, coaches, and administrators. Isabelle Cayer and Peter Niedre (Coaching Association of Canada) explain the culture shifts that have impacted the safe sport movement and various actions to offer and promote training and coach education across the country.

Part 7 highlights sport officials as the lesser known yet essential stakeholder of the sport ecosystem. Spanning two chapters, Lori Livingston and Susan Forbes address the purpose of rules and their role in creating safe playing environments, and outline the role of officials and how officials have been historically maltreated by spectators, coaches and athletes.

Part 8 concludes the book by looking ahead to what needs to happen in order for the UCCMS to be realized. In one chapter, Gretchen Kerr explains why the UCCMS represents only a first step in the safe sport journey and suggests next steps must include the need for independent complaint and adjudication mechanisms, and extending the notion of safe sport beyond the prevention of harms to include optimization of the sport experience. In a second chapter, Michele Donnelly offers a summary of where we currently stand in this safe sport movement, and an important perspective on what steps need to be taken next to put the UCCMS words into action.

In conclusion, the wealth of information in this book offers ways we can counter challenges of structure in order to commit to safe sport values and enact these values through policies and programs. One resounding theme the authors have communicated in their own unique way is that safe sport requires effort from a variety of stakeholders (including you) at every level of the sports system. My hope is to build upon this initial edition by adding new chapters that respond to the evolving conversation about safe sport in our communities.

I am excited to share these insightful scholars and professional accounts from across the sport system, and to work with you to build ways of keeping the “Athletes First” focus at the forefront of our ongoing and collective safe sport efforts.

Yours in safe sport,

![]()

Sources

42 Courses. (October 16). Jeff Bezos’ one empty chair rule. Retrieved January 27, 2022, from https://blog.42courses.com/home/2018/10/16/jeff-bezos-one-empty-chair-rule.

Anders, G. (2012, April 4). Inside Amazon’s idea machine: How Bezos decodes customers. Forbes. Retrieved January 27, 2022, from https://www.forbes.com/sites/georgeanders/2012/04/04/inside-amazon/?sh=ec2d00461998

Ciomaga, B., Thibault, L., & Kihl, L. (2017). Athlete involvement in the governance of sport organizations. In M. Dodds, K. Heisey, & A. Ahonen (Eds.), RouthledgeHandbook of International Sport Business. London: Routledge.

Dolsten, J., Barker-Ruchti, N., & Lindgren, E. C. (2019). Sustainable elite sport: Swedish athletes’ voices of sustainability in athletics. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 13(5), 727-742. DOI: 10.1080/2159676X.2020.1778062.

Grigaliūnaitė, I. & Eimontas, E. (2018). Athletes’ involvement in decision making for good governance. Baltic Journal of Sport and Health Sciences, 3(110), 18-24. https://etalpykla.lituanistikadb.lt/object/LT-LDB-0001:J.04~2018~1579623660997/J.04~2018~1579623660997.pdf

Jackson, G. & Ritchie, I. (2007). Leave it to the experts: The politics of ‘athlete-centeredness’ in the Canadian sport system. International Journal of Sport Management and Marketing, 2(4), 396-411.

Kihl, L., Kikulis, L., & Thibault, L. (2008). A deliberative democratic approach to athlete-centred sport: The dynamics of administrative and communicative power. European Sport Management Quarterly, 7(1), 1-30.

Koetsier, J. (2018, April 5). Why every Amazon meeting has at least 1 empty chair. Inc. Retrieved January 27, 2022, from https://www.inc.com/john-koetsier/why-every-amazon-meeting-has-at-least-one-empty-chair.html

MacIntosh, E., & Weckend-Dill, A. (2015). The athlete’s perspective. In M. Parent & J. L. Chappelet (Eds.), Routledge Handbook of Sports Events Management. London: Routledge.

Thibault, L. & Babiak, K. (2005). Organizational changes in Canada’s sport system: Toward an athlete-centred approach. European Sport Management Quarterly, 5(2), 105-132.

II

Understanding safe sport from the athlete’s perspective is vital as we continue working through safe sport issues in Canada. In Part 2, experts from AthletesCAN, which is the independent association of Canada’s national team athletes, highlight the different forms of maltreatment that athletes experience. Erin Willson and Georgina Truman identify the many ways in which athletes have influenced the Canadian safe sport system, especially in recent years. They also explain the athlete-centred approach to safe sport, and its importance in minimizing maltreatment within sport.

2

Erin Willson

Georgina Truman

Maltreatment in sport

Athlete-Centred approach

Change implementation

When you have completed this chapter, you will be able to:

L01 Identify four types of maltreatment;

L02 Draw connections between athlete advocacy and changes in sport;

L03 Identify 3 key changes;

L04 Explain how the athlete voice has led to key changes; and

L05 Identify key components of the athlete-centred approach. Provide suggestions to implement an athlete-centred sport system.

Maltreatment has become an increasingly documented concern in sport. For example, a 2019 study on Canadian National Team athletes revealed that 75% of athletes reported experiencing at least one harmful behaviour in their careers, with psychological harm and neglect being most common, followed by sexual and physical harm.Willson et al., 2021 In Canada, the athlete’s voice has been an essential component of advancing the safe sport movement, which gained traction in 2018.

First, national team athletes completed a survey on their experiences of maltreatment,Kerr et al., 2009 which was closely followed by a gathering of athletes at the 2019 AthletesCAN Safe Sport Summit, in which reviewed the findings and established consensus statements on the prominent findings and next steps (e.g., a need for an independent body for disclosure/reporting).AthletesCAN, 2019 These statements were presented at a National Safe Sport Summit, which included athletes, national sport organizations and multisport organizations, and led to the formation of a safe sport advisory board and action planning working group.

Since then, a Universal Code of Conduct to Prevent and Address Maltreatment in Sports (UCCMS) has been established and implemented, and a National Independent Mechanism (NIM) is being established by the Sport Dispute Resolution Centre of Canada (SDRCC). This chapter provides an overview of past actions athlete leaders have had in safe sport, including key learnings from this experience about why we believe the athlete’s voice is an essential component of driving change in sport.

This chapter includes multi-media content (videos/audio) of Canadian athletes sharing their experiences with maltreatment, disclosure/reporting concerns, and using their voices to create change. Additionally, it will provide an athlete’s perspective on what is essential to continue the movement toward a safer sport environment, and some practical examples of what safe sport looks like from the eyes of an athlete.

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/safesport/?p=112#h5p-2

There has been mounting evidence of all forms of maltreatment occurring in sport around the world, including physical, sexual, and emotional abuse. Over the past decade, several high-profile cases have emerged, including the USA Gymnastics case in 2016, in which the team’s doctor Larry Nassar was sentenced to 175 years in prison after two hundred athletes came forward with experiences of sexual abuse.Levenson, 2018 The investigation also revealed a culture of emotional abuse and neglect that is rampant in the sport of artistic gymnastics. Athletes around the world have disclosed experiences of body shaming, forced extreme dieting and water restriction, training on injuries and concussions, and frequent public humiliation and beratement.Gymnastic Alliance, n.d.; Levenson, 2018 The USA Gymnastics case was not an isolated incident, with many sports facing similar cases and public allegations, including swimming, alpine skiing, rugby, and artistic swimming.Davison, 2021; Ehekircher, 2020; Longman & Brassil, 2021; Muchnick, 2021 For instance, the British Athletes Commission called for a full investigation of British Gymnastics after several disturbing allegations of bullying and abuse arose in 2020.Ingle, 2021

There have also been research studies conducted from several countries which assessed the prevalence of maltreatment occuring in Canada, Belgium, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom. These studies have indicated high rates of athlete maltreatment in areas including psychological abuse, neglect, physical abuse, and sexual maltreatment across sport.Alexander et al., 2011; Kerr et al., 2019, Parent & Vaillancourt-Morel, 2020; Vertommen et al., 2016 For example, in a study of Canadian National Team athletes, seventy-six percent of athletes from sixty-four sports reported at least one experience of maltreatment in their athletic careers.Kerr et al., 2019

In response to the growing awareness of maltreatment, several prevention and intervention initiatives have been instated. Some Canadian examples include the educational programs by Respect Group’s “Respect in Sport for Activity Leaders”, the Coaching Association of Canada’s Safe Sport Training, and mandatory requirements and standards for federally funded sport organizations, including third party reporting officers.

Most recently, a Universal Code of Conduct to Prevent and Address Maltreatment in Sport (UCCMS) has been implemented to outline all forms of harm in sport that are not acceptable. Furthermore, a National Independent Mechanism (NIM) has been developed to prevent and address maltreatment, and provide an independent body for athletes to report maltreatment. The latter initiatives were heavily influenced by athletes who had spoken out about personal experiences of maltreatment, highlighting the importance that the athletes’ voices carry in the movement towards a safer sport environment. In this chapter you will:

Sport participation offers many benefits that lead to physical, social, and mental well-being (Hansen et al., 2003, Neely & Holt, 2014). However, it is important to acknowledge that there are athletes whose sport experiences have been harmful due to various forms of maltreatment.Willson et al., 2021; Vertommen et al., 2016 Maltreatment refers to: “all types of physical and/or emotional ill-treatment, sexual abuse, neglect, negligence and commercial or other exploitation, which results in actual or potential harm to health, survival, development or dignity in the context of a relationship of responsibility, trust or power”.World Health Organization, 2020

| Type of Abuse | Example |

|---|---|

| Sexual Abuse | Touching or non-touching offenses (e.g., contact, exposure) |

| Physical Abuse | Punching, beating, kicking, biting |

| Psychological Abuse | Yelling, belittling, demeaning comments, humiliation |

| Neglect | Refusing recovery time of injury/illness, inadequate supervision, inadequate attention of basic needs |

| Bullying | Teammate exclusion, theft, teasing |

| Hazing | Initiation specific activities – drinking excessively, personal servant, performing criminal activities |

Power is a fundamental component of maltreatment because violence is often used to assert or maintain dominance over another person.Hu & Liu, 2017; Pense & Paymer, 1986; Russo & Pirlott, 2006 One example of a use of power to establish dominance is veteran athletes using their status as a means to force newcomers to partake in harmful hazing activitiesAllan et al., 2019; Waldron et al., 2011

Hazing is frequently cited as a way for athletes to “know their place” on a team, which reinforces the player hierarchy with senior athletes holding their position of power over junior or new athletes.Waldron et al., 2011 As such, hazing is an example of maltreatment that can happen between peers. Although hazing can result between peers when a power differential occurs through age, rank, seniority, or skill level, it is important to note that athletes are typically prescribed equal amounts of power in the sport system making hazing between peers less likely to be addressed at an institutional level.Kerr et al., 2016

There are several relationships in sport that have predisposed imbalances of power, which can often leave athletes vulnerable. Examples of these relationships include coach-athlete, team captain-athlete, trainer-athlete, and sport administrator-athlete (e.g., CEO of an NSO, high-performance director). Within each of these relationships, athletes are seen to be in a lower position of power since the other roles are positions of authority. Moreover, there is increased vulnerability because of the culture of control and obedience that is instilled throughout sport.

Athletes are taught to respect these positions of authority, which can lead to an unquestioned compliance to the demands from someone in a higher position (e.g., coach).Brackenridge, 1994; Burke, 2001 Moreover, this compliance is often expected from those people who are in positions of power. This power imbalance and unquestioned compliance can significantly reduce an athlete’s power since they are conditioned not to deviate from what is expected of them.

Therefore, our stance at AthletesCAN is to empower athletes by including them in important conversations about their training in order to lessen the power imbalances inherent in sport. It is our hope that steps taken to nurture athlete empowerment will contest traditional methods of coaching and reduce athlete vulnerability .

For more insight about the history of athletes’ involvement in the high-performance sport system, review these resources. In his 2006 thesis and co-authored research article with Dr. Ian Ritchie, Greg Jackson examined the involvement of athletes in Canada’s anti-doping policy process.

Several terms are frequently interchanged when discussing maltreatment in sport. Therefore, this section provides an overview of the different terminologies that are used. Figure 2.1 outlines these terms in a more concise way and is broken down based on the positions of power. The figure indicates that a misuse of power is the underlying mechanism of harm. Abuse is harm that occurs between two actors, with one person having significant influence over another’s sense of security, trust, and/or fulfillment of needs.Crooks & Wolfe, 2007 This is often known as a “critical relationship,” and in sport this can be relationships between athletes and authority figures that commonly interact (e.g., coaches, parents, etc.). Maltreatment between peers is referred to as bullying since athletes are typically within the same prescribed social rank, and in most instances do not have the power differential of a critical relationship. Harassment is maltreatment that occurs outside of a critical relationship. There is typically a power imbalance that occurs between the two actors; however, the perpetrator does not have a direct influence on the others sense of safety or trust. Examples of this could be a sport administrator that only interacts with the athletes occasionally. At the bottom of the diagram are the types of harm that can occur, which will be discussed in the following section.

Psychological harm in sport is defined as “a pattern of deliberate non-contact behaviours that have the potential to be harmful” (Stirling & Kerr, 2008, p. 178). Psychological abuse has been found to be the most frequently experienced type of harm by athletes.Alexander et al., 2011; Vertommen et al., 2016; Willson et al., 2021 Psychological abuse accounts for many harmful behaviours including being yelled at and publicly humiliated. Given the nature of sport, these types of harmful behaviour occur routinely, resulting in the normalization of abusive behaviour and higher rates of psychological harm. Simply put, these behaviours occur so frequently in public training environments that they have become accepted as “part of the game”.Stirling & Kerr, 2008

Stirling and Kerr (2008) have proposed examples of psychological harm, which include:

The most common behaviours reported by Canadian athletes in 2019 were being shouted at, being gossiped about or having lies told about them, and being put down, embarrassed or humiliated.Kerr et al., 2019

Video provided by Brock University Centre for Sport Capacity. Used with permission. [Transcript]

Physical harm is understood to be an infliction of physical pain or injury, which can include contact or non-contact behaviors.Durrant, 2006; Perry et al., 2002 Contact behaviours include hitting, slapping, and punching, whereas non-contact behaviours can include being forced to hold an uncomfortable position for a prolonged period of time.

Physical harm in sport can be:Stirling, 2009

Exercise as punishment (e.g., running laps when late, doing sprints because of poor performance) was the most frequently reported form of physical harm by Canadian athletes in 2019.Kerr et al., 2019

Sexual harm is understood as “Any sexual interaction with person(s) of any age that is perpetrated against the victim’s will, without consent, or in an aggressive, exploitative, coercive, manipulative, or threatening manner”.Ryan & Lane, 1997

Sexual harm in sport can be contact or non-contact including, but not limited to:

The most frequent forms of sexual harm reported amongst Canadian athletes were sexist jokes and remarks and intrusive sexual glances, sexually explicit communication, and sexually inappropriate touching.Kerr et al., 2019

Neglect is characterized by acts of omission or inaction.Brittain, 2006 Examples of this are intentionally ignoring someone or their needs, purposeful exclusion, or purposeful inaction.

Training when injured or exhausted, sacrificing education and/or career, training in unsafe conditions, and inadequate support of basic needs were the most frequently identified behaviours by Canadian athletes.Kerr et al., 2019

Video provided by Brock University Centre for Sport Capacity. Used with permission. [Transcript]

In the middle of the season, a high-performance gymnast was complaining of pain in her heel. Their doctor advised her to take it easy at practice for a month since it could lead to a tear in her Achilles’ heel. Her coach put her on a modified training program, so she would do primary upper body, core, and flexibility training on her own.

The athlete was mostly ignored by the coach because the coach would focus on the other athletes who were “there to train”. One example of the modified training was being told to hold a split position for five minutes on each leg and if her coach felt she was not as flat in her splits as she could be, then the coach would come by and press down on her shoulders to make her legs touch the ground.

Often, tears were formed in the athlete’s eyes because of the sharp pain this extra pressure would cause. She was diligent about training plan but if her coach ever saw her “taking it easy” even if it was for a water or bathroom break, the athlete would be yelled at from across the gym and humiliated in front of all the other gymnasts. As a consequence, she would be forced to complete one hundred push ups and one hundred sit ups to make up for the perceived lack of effort.

Two weeks before the upcoming qualification, the coach told her that if she did not start participating in full practices, she would not be allowed to compete in the qualification which meant she would not be eligible for the larger competitions that season. Knowing this, the athlete decided that she would train full-time against their doctor’s orders.

Which of the four types of harm are being seen here?

AthletesCAN, the association of Canada’s national team athletes, is the only fully independent and most inclusive athlete organization in the country and the first organization of its kind in the world. As the collective voice of Canadian national team athletes, AthletesCAN ensures an athlete-centred sport system by developing athlete leaders who influence sport policy and, as role models, inspire a strong sport culture.

AthletesCAN, the association of Canada’s national team athletes, is the only fully independent and most inclusive athlete organization in the country and the first organization of its kind in the world. As the collective voice of Canadian national team athletes, AthletesCAN ensures an athlete-centred sport system by developing athlete leaders who influence sport policy and, as role models, inspire a strong sport culture.

In 2019, AthletesCAN, in partnership with the University of Toronto, and with the support of the Government of Canada, announced that a baseline prevalence study would be carried out to provide a snapshot of Canada’s national team athletes’ experiences with abuse, harassment and discrimination in sport.

AthletesCAN, the association of Canada’s national team athletes, is the only fully independent and most inclusive athlete organization in the country. It is also the first organization of its kind in the world. As the collective voice of Canadian national team athletes, AthletesCAN ensures an athlete-centred sport system by developing athlete leaders who influence sport policy and, as role models, inspire a strong sport culture.

Mission: To unite and amplify the voices of all Canadian National Team athletes.

Vision: We are the collective athlete voice in the unwavering pursuit of an athlete-centred sport system.

Values: AthletesCAN promotes and lives the following athlete focused values in our work and through our actions

AthletesCAN serves an important and unique purpose in sport. Led by a committed group of current and retired national team athletes – AthletesCAN benefits from a rich history.

Over two decades ago, passionate trailblazers including three-time World Indoor Championship bronze medalist and Pan-Am Champion Ann Peel (Race Walking); two-time Commonwealth Games Champion and two-time Pan-Am Games silver medalist Dan Thompson (Swimming); ‘Crazy Canuck’ and Olympic bronze medalist Steve Podborski (Alpine Skiing); 1988 Olympian, Heather Clarke (Rowing); 2-time Olympic Champion Kay Worthington (Rowing); 1984 Olympian, Sandra Levy (Field Hockey); 1984 and 1988 Olympian, Shelley Steiner (Fencing), Tour de France Women’s Champion, Pan-Am Games bronze medallist and 2012 and 2016 Olympic coach, Denise Kelly (Cycling); and former CEO of Freestyle Canada Bruce Robinson, came together to challenge the Canadian sport system.

They identified the need for and founded an independent body, then known as the Canadian Athletes Association, that would represent all national team athletes as a stronger collective voice on key issues and initiatives in sport. These early days helped to build an increasingly athlete-centred sport system and provided hundreds of athletes with the opportunity to contribute in a number of important ways.

Since then, AthletesCAN has invested in athlete leadership development through effective representation and education. The organization has created resources to build and formalize athlete feedback mechanisms across the sport system. As a result of strengthening strategic partnerships both within and outside of the system, AthletesCAN has continued to pioneer innovative ways to ensure inclusive decision-making by informing, educating, and advocating for an athlete-centred sport system. One of the major contributions in the past few years to the Canadian sport system was ensuring athletes’ voices were heard in the safe sport discussions and policy formations. One of the ways this was done was through a formalized research study in partnership with the University of Toronto, in which athletes were asked about their experiences of maltreatment in sport.

The last prevalence study of Canadian athletes’ experiences was conducted over twenty years ago.Kirby & Greaves, 1996 Since that time, the culture with respect to reporting sexual violence as well as child and youth protection has changed dramatically. Not only does this current prevalence study provide a snapshot of athletes’ experiences but it serves as baseline data against which to assess the impact of future preventive and intervention initiatives. It also signals the importance of addressing the human rights and welfare of athletes in Canada.

The online, anonymous survey was developed by Dr. Gretchen Kerr, Ph.D., Erin Willson, Ph.D. Candidate, and Ashley Stirling, Ph.D., in collaboration with AthletesCAN and the AthletesCAN safe sport working group. The survey was distributed to current national team members as well as retired national team members who had left the sport within the past ten years.

In total, 1,001 athletes participated in the study by completing an online survey. Of this total, seven-hundred-sixty-four were current athletes and two-hundred-thirty-seven were retired athletes who had left their sport within the past ten years.

A discussion of the study’s results is provided in Chapter 17.

In 2019, AthletesCAN, together with their partners, hosted the AthletesCAN Safe Sport Summit in Toronto, Ontario. The event brought together fifty athletes, sport partners, subject matter experts, survivors, and advocates to courageously share their experiences, knowledge, and vision for a safer sport environment from grassroots to high-performance. The results from the prevalence study conducted by Kerr et al., (2019) were shared with the athletes (see Chapter 17 for more information).

After meaningful discussions, the athletes agreed to a number of consensus statements, including, but not limited to the following:

Read the following section to better understand the extent to which each of these six consensus statements has been fulfilled.

Over the past few years there have been significant shifts towards a safe sport environment in Canada. AthletesCAN believes the driving forces of this shift have risen because of the strength in the athletes’ voices. Athletes came together to ensure that safety in sport was a main priority for sport administrators. They did this through formalized surveys and unified consensus statements to ensure their requests and proposed actions for meaningful change were heard. In addition, the Safe Sport Working Group was formed through AthletesCAN as a group of current and retired athletes to represent the collective athlete voice at national practitioner conferences, and in the committees responsible for creating the UCCMS and NIM. As demonstrated by the timeline presented at the beginning of this chapter, many of the critical steps occurred based on the consensus statements from the athletes in 2019.

Statement #1 reads that all forms of maltreatment should be taken into consideration. Previously, the prevention and intervention initiatives in sport had been primarily focused on sexual harm, with policies such as the “Rule of 2” implemented to protect young athletes from being alone with potential sexual perpetratorsCoaching Association of Canada, n.d. (see Chapter 14 for more information on coaching and the “Rule of Two”). The implementation of the UCCMS outlines all forms of unacceptable harm , which includes sexual, physical, physiological and neglectful behaviors.Canadian Safe Sport Program, n.d.

Statement #2 which pertains to all athletes regardless of age, is also incorporated within the UCCMS. The UCCMS does not specify age because there is the understanding that the behaviors outlined can be harmful at any age.Canadian Safe Sport Program, n.d.

Statements #3 and #4 were addressed in 2021 when the National Independent Mechanism (NIM) was established. While the body is not completely independent since it is run through an existing organization, it is a 3rd party resource that equally advocates for all parties (athletes, coaches, sport administrators). In addition, the NIM is also responsible for research, education, and training (statement #3).

Statement #5 has been addressed with the creation and implementation of the Universal Code of Conduct to Prevent and Address Maltreatment in Sport.

Statement #6 has also been addressed through mandatory education that is being provided through the Coaching Association of Canada that was created in 2020. At this time, safe sport training is mandatory for all stakeholders, but there is a lack of data to assess whether this is being upheld.

Given these changes aligned with athletes’ requests, AthletesCAN believes that athletes were an essential part of this movement. However, it is also interesting to note that many decisions made about athletes do not incorporate athletes themselves. For example, many athletes do not have representation or voting rights on their sport organizations’ Board of Directors where many decisions are made. We implore sport organizations to continue collecting feedback from their athletes and incorporating athletes in their decision-making processes. This can be done through formalizing athlete representation into government structures and practices.

Video provided by AthletesCAN. Used with permission. [Transcript]

“Canadian athletes have a proud history of representing this country with honour, class, and overall success. NSOs in Canada work hard to provide the structures which contribute to our athletes’ achievements. In order to best utilize these structures, it is paramount for athletes to both literally and figuratively have a seat at the table. In addition, by including the athlete voice in NSO decision making and governance, Canadian sport institutions will increase their level of effectiveness and transparency, while promoting democratic ideals. Acts of good faith, inclusivity, and a will for success are all virtues needed for promoting the voice of athletes within Canadian sport governance.” – AthletesCAN, 2020

Read the full report “The Future of Athlete Representation within Governance Structures of National Sport Organizations” online.AthletesCAN, 2020

An athlete-centred approach allows athletes to take a more active role in their sporting career, particularly around the decision-making process. Jowett and Cockerill (2003) propose that this approach minimizes the dependency of an athlete on the coach, by becoming an equal contributor in the process. In the 1994 discussion paper “Athlete-Centred Sport” Clarke, Smith and Thibault discuss properties of an athlete-centred sport system:

After the 1988 Ben Johnson doping incident, a formal inquiry was conducted to assess the sport environment.CCES, n.d. This investigation was conducted by Ontario Appeal Court Chief Justice Charles Dubin and was known as the “Dubin Inquiry”. Results from this investigation posited that the win-at-all costs approach that was rampant throughout the Canadian sport culture was detrimental to the health and well-being of athletes.Dubin, 1990 Following this commission, Canada began to make changes towards a more athlete-centred approach, which included the creation of AthletesCAN in 1992 and the Canadian Centre for Ethics in Sport (CCES), then known as the Canadian Anti-Doping Organization (CADO).

Canada has made formal commitments to an athlete-centred approach through policy documents including:

“Dealing with doping: Sports world can learn from Canada and Ben Johnson legacy” by Sarah Bridge, CBC, Feb. 12, 2018.

At the 1988 Summer Olympics in Seoul, South Korea, Canadian Olympic sprinter Ben Johnson won the gold medal in the 100 meter sprint in 9.79 seconds. It was later discovered that he and five other finalists had taken performance-enhancing drugs. What followed was the Dubin inquiry, a historic commission that revealed the ineffective testing policies and procedures of the Canadian government. This inquiry spurred by Johnson’s doping revelations resulted in the establishment of the Canadian Anti-Doping Organization (CADO), an independent body that oversees nationwide drug testing. The CADO is known today as the Canadian Centre for Ethics in Sport (CCES). The Dubin Inquiry focused upon high-performance athletes rather than the sport system as a whole when identifying reasons why performance enhancing drugs were prevalent in Canadian high-performance sport.

What do you think sport leaders have learned from this scandal about implementing an athlete-centred approach? What lessons still need to be implemented?

Video provided by AthletesCAN. Used with permission [Transcript].

One of the main challenges identified by athletes is that they do not feel they have a safe place to report maltreatment. Most complaints must be brought to the athletes’ superiors, who have power over the decisions that are made against the athlete. For example, a national team athlete who had an issue with a coach would need to go to the national sport organization to submit a complaint, but this could also have implications for their own careers since the sport organizations makes decisions on team selection. Many athletes feel as though they do not have a safe place to report their experiences.

Video provided by AthletesCAN. Used with permission. [Transcript]

During her presentation at the 2021 Safe Sport Forum hosted by the Centre for Sport Capacity at Brock University, Allison Forsyth, Olympian and AthletesCAN board member, addressed the difficulty an athlete faces when reporting maltreatment. The following six themes related to perceived barriers are highlighted by these direct quotes provided by athlete participants in the maltreatment study.Kerr, et al., 2019

“While some could view the outcomes of this study as negative, highlighting the extreme nature of the issues and having a baseline to then work from to effect change is actually positive.”

“Athletes rarely report. Plain and simple. They are not comfortable or feel safe doing so with anyone who has a vested interest in the outcome. I reported and did not experience a positive outcome. It is not easy being the whistle blower. We need to support athletes through this – they need a safe place to report free from conflict of interest.”

“The reporting system is broken or useless as it stands right now. Other coaches knew about abuse and did nothing. Turning a blind eye was the norm. Everyone feared consequences of confronting the issues.”

“When an athlete or team says that the coach is unfit and that her behaviour is considered harassment, listen! It is not ok to “wait and see” what will happen and expect that all problems will resolve themselves. When twelve people give you different instances of unacceptable behaviours, that means there is a problem, don’t tell your athletes that they are “just being dramatic and will have to deal with it.”

“I did not make a formal complaint because the process was lengthy and I was afraid of repercussions and mentally it would be difficult to deal with and continue training.”

“If athletes speak out or questions decisions, they are told to be quiet.”

“My NSO did support me very well during a harassment investigation. The parties accused were found guilty but very minor consequences were given. The harassment put a cloud over my entire career.”

“Over 5 players have left our program due to mental health issues in direct correlation with the head coach. Our team finished 3rd so they kept him on board despite the abuse.”

Athletes’ voices are often ignored in the conversation of maltreatment. Reasons athletes have received for not being included are:

“This included the use of conflict of interest to exclude athlete representative positions from NSO boards, issues with recruiting athlete representatives who lack the preferred board member skills and qualifications, as well as geographical barriers which may prevent athletes from attending board meetings and performing their athlete representative role.”AthletesCAN, 2020, p. 19

Normalization of behaviours, grooming contributes to a lack of education.

“All athletes, coaches and sports officials should take a mandatory Safe Sport course.”

“Coaches should be required to go through training to help them navigate harassment and abuse issues between team members. My coach always put his head in the sand and used the ‘that’s not my job’ excuse. I know there is a focus on dealing with harassment and abuse perpetrated by coaches, but I think that issues between peers also must be seriously addressed.”

“More education is needed on ‘It’s not okay to do X’ anymore.”

“Teach male coaches that it isn’t appropriate to talk about sexual things, whether or not they relate to the athlete, ever. Teach coaches to not discuss the negatives of their personal/home life with the athlete, ever.” As one athlete wrote, “Coaches are educators. Most math teachers would be fired for negatively screaming at a person for a wrong answer. Out with the old in with the new.”

Video provided by Brock University Centre for Sport Capacity. Used with permission. [Transcript]

There continues to be improvements and action toward a safer sport environment for all, however, there is still great deal that must be done. We believe one of the most essential parts of this movement are the athletes, which includes their protection and their voice within this movement. We believe the best way forward is through a collaborative approach with all stakeholders, including sport administrators, sport organizations, coaches, and athletes. This does not necessarily mean that athletes get “all the power” but we do propose that athletes are involved in a meaningful way.

Moreover, this means removing the “us vs. them” mentality that continues to persist between sport stakeholders, specifically between athletes and other stakeholders. There are concerns that if athletes have more power then there will be chaos in sport, and it will no longer be manageable. We are at a moment in time where athletes are demanding protection, and we believe that a system that includes all stakeholders’ voices and puts athletes at the centre of all decisions will lead to a safe, welcoming, and inclusive sport environment.

Key Terms

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/safesport/?p=112#h5p-3

Suggested Assignments

Image Descriptions

Figure 2.1 This figure demonstrates the differentiation between relationships and terms including bullying, abuse, and harassment. Maltreatment is committed through the misuse of power. Within a dependent relationship this is called abuse. Between peers this is called bullying. Within an authority-based, non-dependent relationship this is called harassment. These three types of harm are manifested in physical, psychological and sexual harm, as well as neglect. [return to text]

Figure 2.2 This figure demonstrates the nine characteristics of an athlete-centred system which include accountability, dual respect, empowerment, equity & fairness, excellence, extended responsibility, health, informed participation, mutual support, and rights. [return to text]

Sources

Alexander, K., Stafford, A., & Lewis, R. (2011). The experiences of children participating in organized sport in the UK. The University of Edinburgh: Child Protection Research Centre.

Allan, E. J., Kerschner, D., & Payne, J. M. (2019). College student hazing experiences, attitudes, and perceptions: Implications for prevention. Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice, 56 (1), 32-48. https://doi.org/10.1080/19496591.2018.1490303

AthletesCAN. (2019, May 2). Athlete leaders unite to influence safe sport policy in Canada. Retrieved December 30, 2021, from https://athletescan.com/en/athlete-leaders-unite-influence-safe-sport-policy-canada

AthletesCAN. (2020). The future of athlete representation within governance structures of national sport organizations. https://athletescan.com/sites/default/files/images/the_future_of_athlete_representation_in_canadavf-en3.pdf

AthletesCAN. (n.d.a). Retrieved December 30, 2021, from https://athletescan.com/en

AthletesCAN. (n.d.b). Our story. Retrieved December 30, 2021, from https://athletescan.com/en/about/our-story

BBC News. (2018, January 25). Larry Nassar case: The 156 women who confronted a predator. Retrieved December 30, 2021, from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-42725339

Brackenridge, C. H. (1994). Fair play or fair game? Child sexual abuse in sport organisations. International review for the Sociology of Sport, 29(3), 287-298.

Brittain, C. R. (2006). Defining child abuse and neglect. Understanding the medical diagnosis of child maltreatment: A guide for nonmedical professionals, 149-189.

Burke, M. (2001). Obeying until it hurts: Coach-athlete relationships. Journal of the Philosophy of Sport, 28(2), 227-240.

Canadian Centre for Ethics in Sport. (n.d.). History of anti-doping in Canada. Retrieved December 28, 2021, from https://cces.ca/history-anti-doping-canada

Canadian Heritage. (2021, July 6). Minister Guilbeault announces new independent safe sport mechanism. Government of Canada. Retrieved October 27, 2021, from https://www.canada.ca/en/canadian-heritage/news/2021/07/minister-guilbeault-announces-new-independent-safe-sport-mechanism.html

Canadian Safe Sport Program. (n.d.). Sport Information Resource Centre: Universal Code of Conduct to Prevent and Address Maltreatment in Sport (UCCMS), 5(1), 1-16. https://sirc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/UCCMS-v5.1-FINAL-Eng.pdf

Clarke, H., Smith, D., & Thibault, G. (1994). Athlete-centred sport: A discussion paper. https://athletescan.com/sites/default/files/images/athlete-centred-sport-discussion-paper.pdf

Coaching Association of Canada. (n.d.). Three steps to responsible coaching. Retrieved December 28, 2021, from https://coach.ca/three-steps-responsible-coaching

Comeau, G. S. (2013). The evolution of Canadian sport policy. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 5(1), 73–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/19406940.2012.694368

Crooks, C. V., & Wolfe, D. A. (2007). Child abuse and neglect. In E. J. Mash & R.A. Barkley, (Eds). Assessment of Childhood Disorders (4th ed.). New York: Guilford Press, 1–17.

Davidson, N. (2021, April 28). Ruby 7s women say they were let down by Rugby Canada’s bullying/harassment policy. The Canadian Press. Retrieved December 28, 2021, from https://www.cbc.ca/sports/rugby/rugby-sevens-women-let-down-rugby-canada-bullying-harrassment-policy-1.6005901

Dichter, M. (2021, October 8). NWSL’s abuse scandal reveals normalization of toxic culture in sports. CBC Sports. Retrieved December 30, 2021, from https://www.cbc.ca/sports/soccer/nwsl-soccer-abuse-symptom-culture-1.6204197

Dubin, C. L. (1990). Commission of inquiry into the use of drugs and banned practices intended to increased athletic performance. The Honourable Charles L. Dubin Commissioner.

Durrant, J. (2006) Distinguishing physical punishment from physical abuse: Implications for professionals. Canada’s Children, 9, 17–2.