Introduction to Logistics

Introduction to Logistics by Robert Adzija and Michael Kukhta is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Conestoga College

Kitchener, Ontario, Canada

Introduction to Logistics by Robert Adzija and Michael Kukhta is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

1

Welcome to Introduction to Logistics, an introductory text focused on moving and storing products in a manufacturing supply chain. We hope it will help you understand what a logistics person, operating domestically or internationally, would need to know to plan, implement and analyze logistics functions and operations. You can investigate the modes of transportation, types of warehouses, costs, services, tradeoffs, and risks that are the significant challenges for all supply chain managers. This book discusses strategies and methods that can add value to a company’s supply chain by improving a logistics network’s productivity, effectiveness, and customer service. This book examines international logistics, vendors, customers, and distribution centers and discusses considerations for comparing the logistics impacts for local and global opportunities.

This OER presents learning materials that reside in the public domain or have been released under licenses or agreements that permit no-cost access, use, adaptation, and redistribution by others.

Students: this OER is different from many traditional textbooks. Interactives, pre-and post-assessments, and other content has been built into each chapter to create a holistic, engaging learning tool. The interactive content serves to reinforce your learning. The pre-and post-assessment activities serve as knowledge checks for your progress.

Faculty and teaching staff: This first version has been created by Michael Kukhta from Conestoga College and Robert Adzija from Fanshawe College to keep this material current by others updating, adapting, and resharing content. This OER will grow as more people contribute to it. We hope that you take this OER and customize it for your program and share it again.

Robert Adzija BA, MBA, P.Log.

Robert is a faculty member in the Lawrence Kinlin School of Business at Fanshawe College in London, Ontario and can be reached at r_adzija@FanshaweC.ca. His career focus has been optimizing logistics networks and improving supply chain visibility. During the 19 years of working in the manufacturing Supply Chain, Robert has led several strategic paradigm shifts. He conceptualized, reorganized, and implemented a new ocean freight strategy, resulting in direct cost savings while improving inventory visibility. Robert has set strategy, negotiated LLP and carrier contracts, and led transition teams. By collaborating with Global Purchasing, Global Logistics and Global Packaging leaders, he has uncovered process blind spots and influenced strategic business process shifts. Robert is passionate about utilizing his industry experience to educate and prepare our future Supply Chain Leaders.

Michael Kukhta, B.Eng. (Mechanical), P.Eng.

Michael Kukhta is a faculty member in the School of Business at Conestoga College, in Kitchener, Ontario and can be reached at mkukhta@conestogac.on.ca. Michael is a fulltime professor on the Supply Chain and Operations Management program team where he helps students develop skills and prepare for the work world. Michael is a Professional Engineer with management and teaching experience in the automotive, aerospace and social services sectors. Michael is a Six Sigma Lean Master Black Belt and has coached and guided many people and organizations to help them improve their performance.

[Automatic Warehouse] by Arno Senoner on Unsplash. Licensed for reuse under the Unsplash License.

2

This project is made possible with funding by the Government of Ontario and through eCampusOntario’s support of the Virtual Learning Strategy. To learn more about the Virtual Learning Strategy visit: https://vls.ecampusontario.ca.

3

We wish to acknowledge Indigenous peoples for their contributions as we work towards reconciliation by learning about the people, the land, and traditional territories on which we work and reside. Conestoga College is located on the traditional territory of the Anishnawbe, Haudenosaunee, and Neutral peoples. Fanshawe College is located on the traditional lands and waterways of the Anishinaabe, Haudenoshaunee, and Lenape people.

We wish to acknowledge and thank the following list of people who supported and participated in this project.

Barbara Kelly PhD, Vice-President of Academic/Student Affairs/Human Resources and Research

Gary Hallam MSc., Vice President, International & Executive Dean School of Business, School of Hospitality & Culinary Art

Michelle Grimes PhD, Dean School of Business

Jeff Fila PhD, Director of Special Projects

James Boesch CPA, CMA, M.Ed., Chair School of Business

Mary Pierce BA MA (ED), Dean, Faculty of Business, Information Technology, Part-time Studies, London South Campus, Acting Associate Dean – Lawrence Kinlin School of Business

Lisa Schwerzmann BA MA, Associate Dean of the Lawrence Kinlin School of Business, Fanshawe College CAAT

Kevin Hollis MBA, BSc, PMP, Conestoga College ITAL for providing a peer review and development of ancillaries.

Holly Ashbourne, Hon. BA, MLIS Conestoga College ITAL, liaison to accessibility and library supports, for providing a final review, and countless support with Pressbooks technology through workshops, diving into Pressbooks to have a look, and answer numerous questions.

Erjona Ferizi, our OER Projects Assistant, who on her co-op from the Bachelor of Public Relations program at Conestoga College ITAL provided ongoing administrative support, coordinated events, and completed extensive first-line copy edits, accessibility checks, labelling multiple images and participating in content creation.

James Yochem, Hon. BA, MLIS Copyright Coordinator, Conestoga College ITAL for answering numerous copyright and copy edit questions.

Kimberlee Carter, BEd., MA, Open Educational Resources (OER) projects consultant, Conestoga College ITAL for spearheading this OER project and keeping us on track.

Antonina Gousseva, BA, Dipl. LIT, Conestoga College ITAL for ensuring this resource met all accessibility requirements.

Juliet Conlon, MLS, Conestoga College ITAL for support in searching out existing OER.

Elan Paulson, PhD, Teaching and Learning Consultant Conestoga College ITAL for providing consultations on design for learning.

We have done our best to acknowledge all participants involved and with correct job titles and credentials. In the event, we have made an error please reach out to any one of the authors to have this corrected.

A supply chain is a network that creates products and services and delivers those products and services to customers. Supply chains include marketing, sales, financing, procurement, processing operations, maintenance, service, and logistics. The focus of this Open Educational Resources (OER) digital textbook is logistics. Logistics refers to the processes and networks used to move and store materials within supply chains and move products to their final destination. Logistics is considered a subset or part of a supply chain.

The coffee sitting on your desk and the food in your home arrived via a product supply chain. The computer you are using to access the information in this OER came via a product supply chain. The digital information you are reading (in the form of electrons and signals) is available for use thanks to an information supply chain. A haircut appointment or a lawyer’s appointment are examples of activities that provide services to you as part of a service supply chain. In this chapter, we will explore the role of logistics in supply chains.

Figure 1.1

Coffee Cup on Desk

Note: From Scott, 2021. CC BY 2.0

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/logistics001oerfc/?p=5#h5p-1

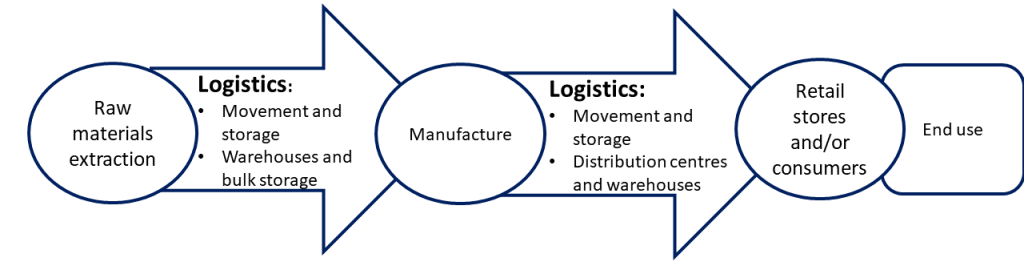

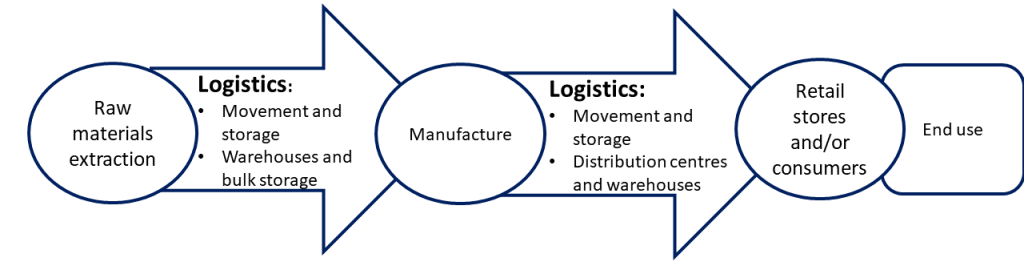

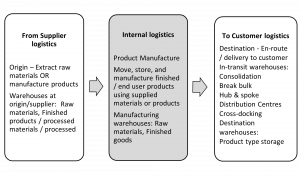

Product supply chains start with the demand from a customer for a product. Products begin in the form of raw materials that must be sourced, gathered, converted, and manufactured into the required products. Then, the product is transported to end-users. Products will often stop at warehouses as they move through the product supply chain. There are many steps to convert and transform raw materials into final products that will be delivered to a consumer. Logistics supports the transportation steps in supply chains. Logistics can be categorized as :

Figure 1.2

Note. From Kukhta, 2021. [Image Description]

The information generated by each process in a supply chain supports the supply chain’s logistics networks and operations. This information is itself a supply chain. Consider that similar to products, information is comprised of raw materials such as data and artifacts, that are processed into information such as knowledge, documents like bills of lading, certificates such as health and safety certificates, approvals, and reports. Logistical activity is required to move that information and then store it. In contrast to the physical movement of products, information is moved or transmitted through information systems and electronic data interchange (EDI). Information can be found in reports that need to be distributed in hardcopy, digital, and electronic formats. Storage then takes place in databases, servers, and data warehouses.

Services like haircuts, accounting services or legal advice also have a supply chain. Services unlike products are typically intangible and require supply chain processes that acquire products, knowledge, and develop talent that will be used in the provision of services to customers. Logistics for services depends on producing and supplying products like scissors for barbers, computers for accountants, and cyber-secure information systems to ensure confidentiality of electronic documents for paralegal services.

Whilst downstream logistics refers to the forward movement of raw materials through multiple steps of production, storage, and transportation of final products, upstream logistics refers to the reverse direction movement of products from the customer back through one or more steps of the forward logistics process.

Reverse Supply Chains, therefore, refer to the backward flow of products from downstream to upstream in a supply chain. This process may occur if an item is returned to the manufacturer due to damage, for example, reverse logistics would move these products back to their point of origin or another destination, such as a repair center, upstream in the process.

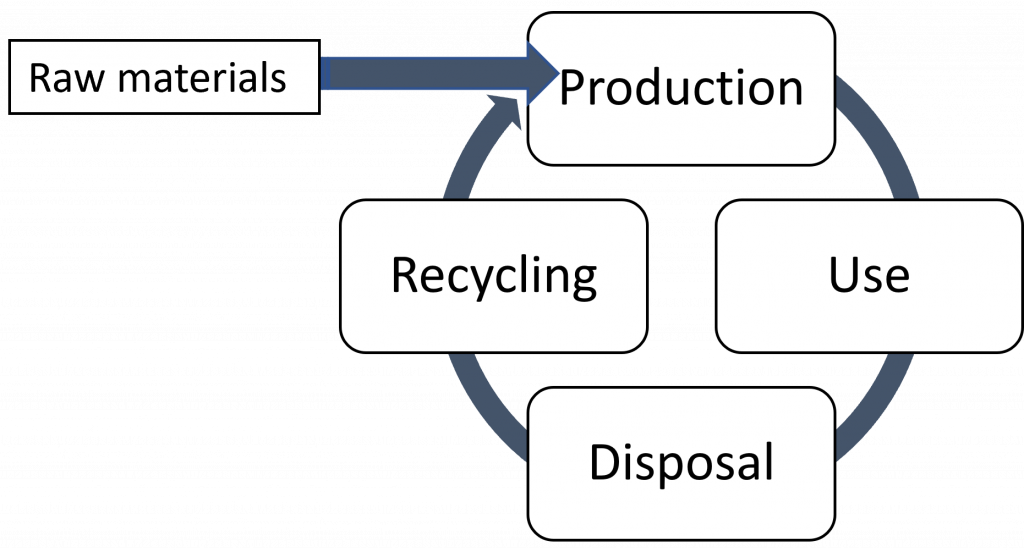

Circular Supply Chains are a development from the traditional linear product supply chain. They start with raw materials, convert them to products, and then back to the raw materials from whence they started. These types of supply chains emphasize reusing waste materials and returned or old products. Sustainability, social, and economic responsibility are integral to circular supply chains.

Logistics in supply chains considers the total system cost in planning and managing the transportation and storage of products. Starting from the extraction point of the raw materials back to the re-entry of these same raw materials after their initial product life has expired, back into the beginning of a new supply chain in the next life cycle they will experience.

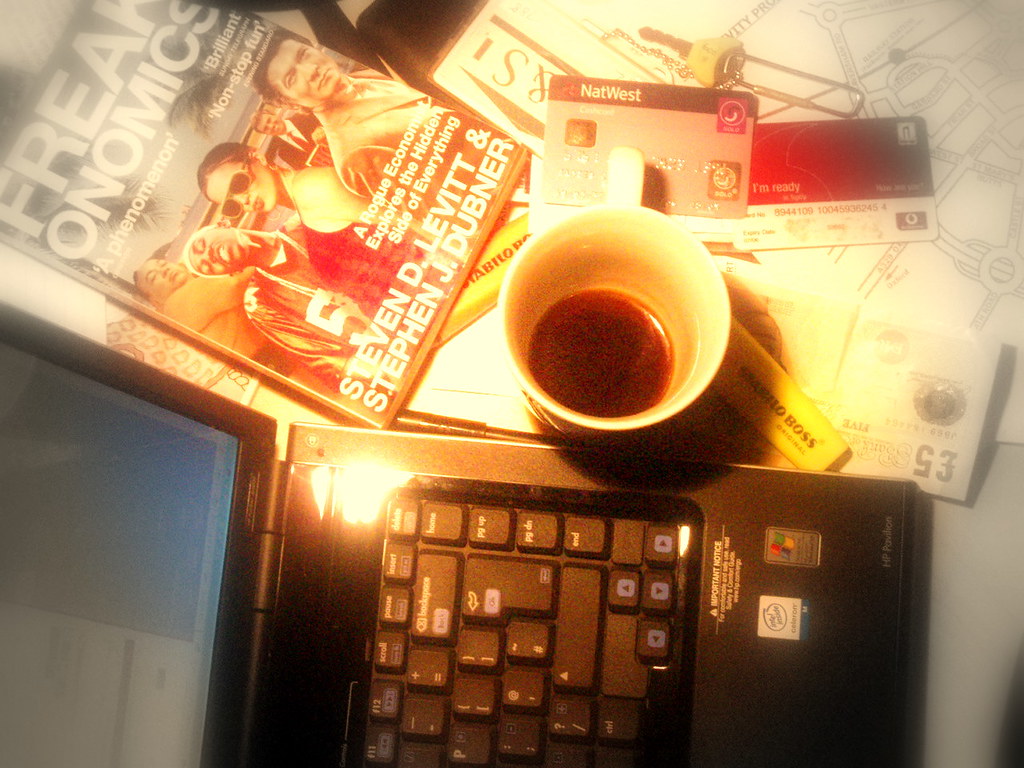

Figure 1.3 shows a simple linear supply chain. In the supply chain, Tier 2 represents raw materials suppliers. Tier 1 represents the sub-assembly parts made from those raw materials. They are then manufactured into products and distributed to retailers where customers, the end-consumer or user, acquire them. This progression represents the forward flow of materials/goods. Other “flows” include the flow of information that runs up and downstream, the flow of money which runs from downstream to upstream, and the reverse flow of materials when a product is returned to the manufacturer (for example, if a product is damaged). Logistics, represented by the blue arrows that connect each tier and each step in the supply chain, are required to manage all of the flows and movement in a supply chain.

Figure 1.3

Upstream and Downstream of a Supply Chain and its Flows

Note: From Faramarzi, H., & Drane, M. CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0 [Figure Description]

The following is a list of common variations to a linear supply chain:

This video demonstrates a product supply chain for bottled water. The logistics component of this supply chain is made up of the trucks that transport the bottled water and the forklifts that load and unload the inventory. Consider the cost of a bottle of water, typically $1.50 or $2.00. How much of that cost goes toward the water, processing, packaging, and the cost of logistics that is spent moving and storing the bottle of water?

W.P. Carey School of Business. (2010, April 6). Module 1: What is supply chain management? (ASU-WPC-SCM) – ASU’s W. P. Carey School [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/Mi1QBxVjZAw

Supply Chain Management is often abbreviated as SCM. Supply chain management is the management of goods and services from the initial idea to the end-users and back to their origin. Supply Chain Management includes procurement (or purchasing) demand planning, sales and operations planning (S&OP), execution and management of supply chain activities, strategic sourcing, transportation management, warehouse management and inventory management. According to APICS Dictionary, 13th edition, it involves the design, planning, execution, control, and monitoring of all supply chain activities. SCM includes:

This video offers definitions and explains the role of managing logistics in a supply chain.

Aims Education, UK. (2016, July 21). What is logistics management? Definition & importance in supply chain [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/4-QU7WiVxh8

Materials and products also need to be moved and stored when they are inside a manufacturer’s facility, inside a distribution centre and when you bring them home. This OER will focus on the logistics between Suppliers and Manufacturers, between Manufacturers and Distribution Centres, between Distribution Centres and Retail stores and between Distribution Centres and Customers, in other words, beforeand afterthe manufacturing/assembly process.

Logistics occur at every step and help the product move through the supply chain from origin to end-user. This is known as Forward Logistics which means product moving forward or downstream from the point of origin (e.g. supplier, manufacturer) to point of consumption (e.g. end-user, customer), or expressed differently, from raw materials to the final product destination. Forward logistics can take place between:

Product moving backward or upstream from the customer back to the supplier or manufacturer is called reverse logistics.

Reasons for using reverse logistics:

Figure 1.4

Nespresso Expands Aluminum Recycling and Reuse

Note. From Nestlé, 2008. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

“Reverse logistics has been a part of retailing for over 100 years when retailers like Sears Roebuck and Montgomery Ward began delivering goods by railroad. In the past few years, e-commerce has led to an explosion of reverse logistics — or, shipping goods from the consumer back to the retailer. Consumers have come to expect no-fuss return policies; that’s why returns on e-commerce orders are three to four times higher than brick and mortar purchases, according to the Reverse Logistics Association. That means reverse logistics is a fact of life for most companies.” (Syverson, 2021, paras. 1-2).

“Reverse logistics are a very important part of a circular supply chain that finds new uses and/or ensures proper disposal of products that are at the end of their life cycle. Recycling bottles, plastics, batteries and other materials are part of the reverse supply chain.” (Guest Blogger, 2017). Reverse Logistics 101 discusses several successful examples of manufacturers like Apple, H&M, and Dasani using reverse logistics in their processes.

Managing inventory is one of the most important activities in a supply chain. Materials/goods are needed to provide manufacturers with the exact items they need, in the right order, the right quality delivered to the right location, and at the right time. Without all of this happening, it will be impossible to produce high-quality goods and meet commitments to our customers. In addition, when goods are ready for shipment, the outbound supply chain needs to be organized in such a way that customers receive their requested orders in a cost-efficient manner.” (Faramarzi & Drane, n.d., Chapter 7)

This section was adapted from Chapter 7: Supply Chain Management from Introduction to Operations Management by Hamid Faramarzi and Mary Drane, Seneca College, licensed for reuse under CC BY-NC-SA.

Many reasons exist for keeping stocks of inventory. Some of the most common include:

Inventory that is moved and stored in the logistics network can be of any of the types listed above. The cost of inventory and logistics increases as you move downstream through the supply chain. Finished goods are more expensive than other types of inventory because they acquire value through the manufacturing process and the supply chain.

This section was adapted from Chapter 7: Supply Chain Management from Introduction to Operations Management by Hamid Faramarzi and Mary Drane, Seneca College, licensed for reuse under CC BY-NC-SA.

Is there an end to logistics? Is the life cycle of a product linear or straightforward; a product starts with an idea or a need, then is finished when the product is no longer needed or can no longer perform its intended purpose? So what happens to the product at this point? It might just sit around. Do you have a drawer full of old electronics products?

Figure 1.7 shows a drawer open with an old hard drive, a Blackberry, an iPhone 3, and various memory storage devices. In a linear economy, they would just be thrown out into landfills. Could obsolete products be repurposed? I re-purposed my old iPhone 3 as an iPod that I hooked up to my stereo to listen to saved songs and streamed content from the internet for a long time.

Figure 1.5

Obsolete Electronics in a Drawer

Note. From Kukhta, 2021

In a circular economy, obsolete products such as those shown in Figure 1.7 might be repurposed, reused, or recycled for parts. They might be broken down into their sub-components or raw materials so they can re-enter the supply chain in a new form. In a circular economy, the initial design of products, supply chain, and logistics need to be planned and managed differently. They need to take into account reverse logistics for the successful continuation of the product’s life cycle.

A good question to consider is what happens to materials and products on a supply chain after consumers are done with them? Look around you and ask yourself what will happen to your clothes, products you are using, or the leftovers from services with which you engage? There are many ways to make products and services. There are a wide variety of materials and processes used to make them. Products and services are made using energy from many different sources – both renewable and from sources that produce much pollution.

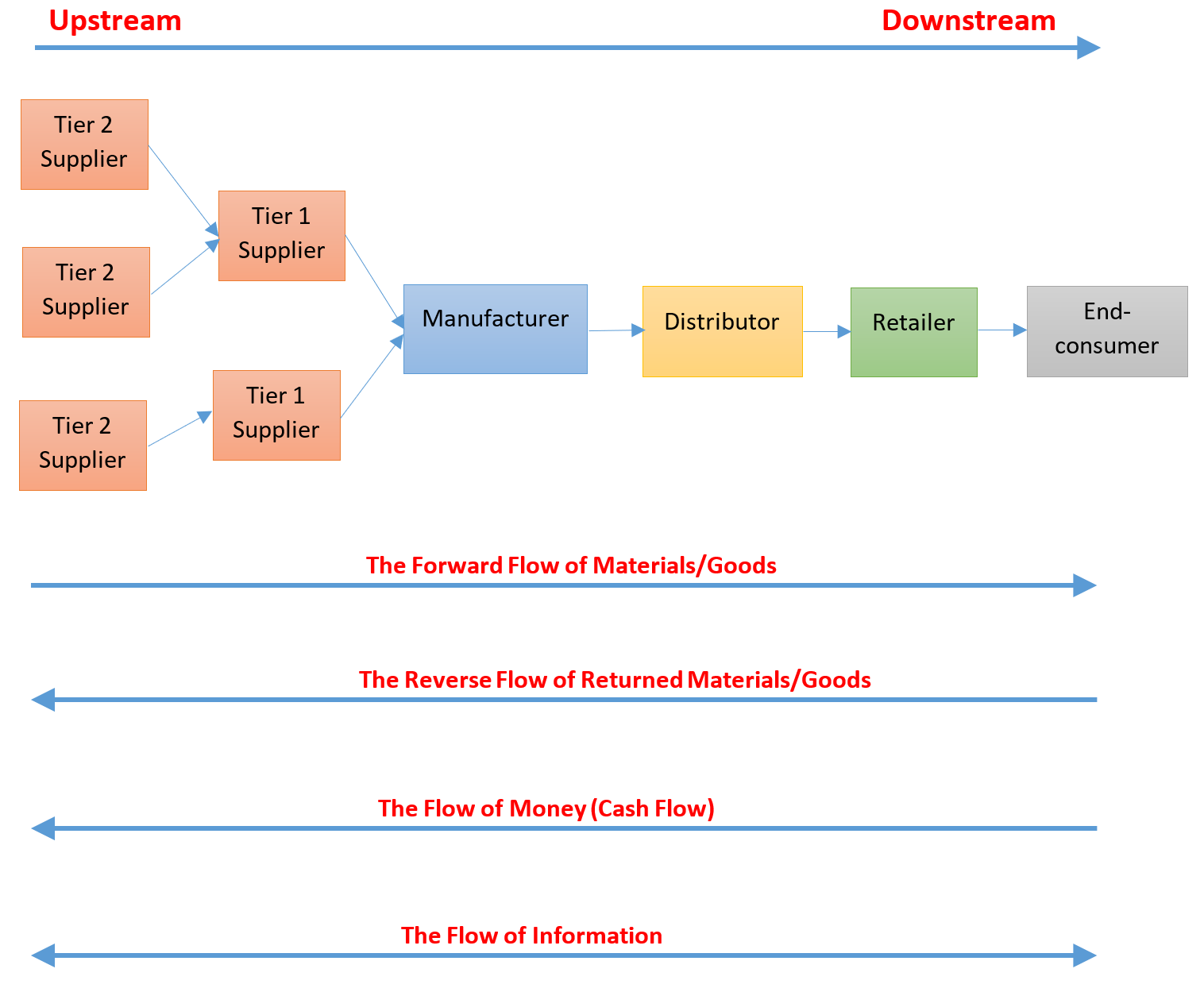

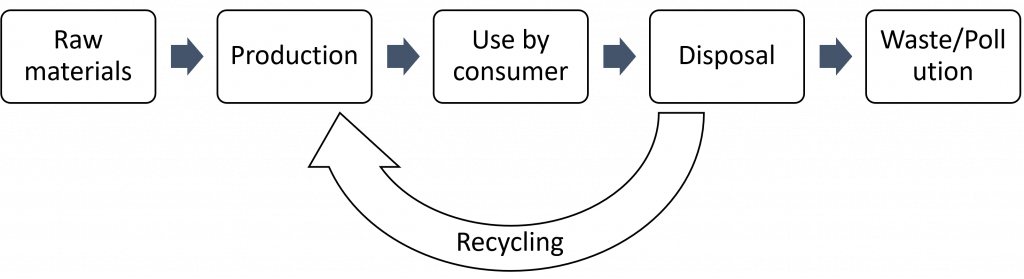

This image shows a linear economy with a straight line from raw materials to landfills; a reuse economy showing new use of materials, and a circular economy cycle that re-uses materials.

Linear, Reuse, and Circular Economies

Note. From Kukhta, 2021 [Image Description]

A linear economy, shown at the top of Figure 1.8, follows a traditional “take-make-dispose” plan. This type of economy involves collecting raw materials and transforming them into products that will be used until they are discarded as waste. In the linear economic system, value is created by producing and selling as many products as possible.

The linear economy often ignores the costs of waste generated during manufacturing and costs incurred after the useful product life has ended. The total system costs, including processing, disposal, and logistics (handling and storage) are considered.

An example of linear supply chains and unaccounted for costs of disposal and cleanup are discussed in an article in The Narwhal about Canada’s oilsands and old oil wells:

“Ottawa is paying to clean up Alberta’s inactive wells. Are the oilsands next? As $1 billion in federal funds go to clean up inactive wells, experts are sounding alarm bells about the ‘super experimental’ realm of tailings ponds reclamation and what could be more than $100 billion in unfunded liabilities in the oilsands” (Riley, 2020, para. 1).

A reuse or recycling economy, shown in the middle of Figure 1.8, includes collecting raw materials and transforming them into products. It is similar to a linear economy model. However, unlike the linear economic model, some of those product materials can be put back into the value stream and reused to manufacture new products or distribute more products. In contrast, other products are disposed of as waste. The design, planning, and managing of logistics must consider the recycling process steps, transportation modes, storage, and costs in this type of economy.

An example of this is the Blue Box program for collecting recyclable materials in Ontario, Canada. This article by Stewardship Ontario discusses how costs for processing recycled materials are going up, yet revenues from them are decreasing.

The circular economy, shown at the bottom of Figure 1.8, is an alternative to Canada’s dominant linear economic model. It is grounded in the study of living systems and nature itself. We are pretty used to collecting and transforming resources that are later consumed and become waste once their lifespan ends.

If you look at nature, you can see that processes are different. A tree is born from a seed, it grows and reproduces, and when it dies, it goes back to the soil, enriching it and providing nourishment for new life. How could we apply that process to the objects we use at home and work?

The circular economy looks at all the options across the supply chain to use as few resources as possible. It seeks to keep resources in circulation for as long as possible, extract the maximum value from them while in use, and recover and regenerate products at the end of their service life. The circular economy tries not to view garbage as waste but as a potential resource to be reused. This new way of understanding goods also means designing products using materials that can be easily dismantled and recycled when their initial life cycle is done.

In a circular economy, one considers the impact of materials, resources, and energy used to make products, move them and store them. The goal is to maintain their value for as long as possible, including returning them back into the manufacturing cycle.

The Government of Ontario is changing supply chain rules by shifting responsibility for recycling products at their end of life to their producers. This change will impact where costs are assigned in the logistics networks: “the price of packaged goods expected to go up as costs of recycling shift entirely to producers” (Dunn, 2020, para. 1).

The following organizations are led by experts and interested members who work in supply chains. They conduct research, share knowledge, advocate, train, and provide platforms for learning and discussing what is happening in the industry. They often have student chapters.

The Council of Supply Chain Management Professionals (CSCMP) is an organization based in the United States that helps people working in the supply chain field connect, network, understand and develop supply chain networks. Professional organizations like this have current and relevant information about supply chains and logistics within supply chains.

CSCMP defines logistics management as “that part of supply chain management that plans, implements, and controls the efficient, effective forward and reverses flow and storage of goods, services and related information between the point of origin and the point of consumption in order to meet customers’ requirements.” (Council of Supply Chain Management Professionals, n.d., para. 5).

CSCMP further defines the boundaries and relationships that logistics management has in relation to the rest of the supply chain:

“Logistics management activities typically include inbound and outbound transportation management, fleet management, warehousing, materials handling, order fulfillment, logistics network design, inventory management, supply/demand planning, and management of third-party logistics services providers. To varying degrees, the logistics function also includes sourcing and procurement, production planning and scheduling, packaging and assembly, and customer service. It is involved in all levels of planning and execution–strategic, operational, and tactical. Logistics management is an integrating function, which coordinates and optimizes all logistics activities, as well as integrates logistics activities with other functions including marketing, sales manufacturing, finance, and information technology.” (Council of Supply Chain Management Professionals, n.d., para. 7).

Supply Chain Canada (SCC) is a Canadian organization that is similar to CSCMP. SCC’s vision is “to ensure Canadian supply chain professionals and organizations are recognized for leading innovation, global competitiveness, and driving economic growth” (Supply Chain Canada, 2021, para. 1). Its mission is to “provide leadership to the Canadian supply chain community, provide value to all members, and advance the profession” (Supply Chain Canada, 2021, para. 2).

The Association for Supply Chain Management (ASCM) is “the global leader in supply chain organizational transformation, innovation, and leadership. As the largest non-profit association for supply chains, ASCM is an unbiased partner, connecting companies around the world to the newest thought leadership on all aspects of the supply chain.” (6). ASCM has many resources for supply chain professionals. ASCM has certificate training programs on supply chain subjects, including a Warehousing Certification program.

Joining and participating in activities with professional organizations like these are valuable for networking, learning, and staying current with the activities and practices in supply chains.

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/logistics001oerfc/?p=5#h5p-2

“While in Tokyo, Japan, I noticed that there were two sizes for cans of Coca-Cola in a vending machine – 10 fluid oz. (approx. 296 ml) and 12 fluid oz. (approx. 355 ml). However, both were the same price. I asked a Japanese friend why this was the case. Wouldn’t everyone just pick the bigger one, as I did, for the same price? He said that he usually bought the 10 oz. can because that was all he wanted to drink. He did not need the other two oz., so why buy it and waste it? The message is that the Coca-Cola supply chain satisfied the demand for two different customers, but the cost of the extra 2 oz. of Coke was insignificant to the cost of the logistics of supplying the product, leading to the same end cost.” (Kukhta, 2021)

In this chapter, we have explained the role of logistics in supply chains. Logistics supports the transportation of raw materials and products between locations or facilities as they move along the supply chain ending their initial life with the consumer. The circular economy follows a product through its next phases where it is discarded or moves back into the supply chain. We have considered elements such as defective products and inventory that make up a logistics network, examined the importance of logistics to the economy, and provided a review of a supply chain professional organizations and associations.

Association for Supply Chain Management. (2021). Contact us. ASCM. https://www.ascm.org/contact-ascm/

Council of Supply Chain Management Professionals. (2021). CSCMP supply chain management definitions and glossary. CSCMP. https://cscmp.org/CSCMP/Academia/SCM_Definitions_and_Glossary_of_Terms/CSCMP/Educate/SCM_Definitions_and_Glossary_of_Terms.aspx?hkey=60879588-f65f-4ab5-8c4b-6878815ef921

Dunn, T. (202, October 20). Ontario’s new blue box plan will recycle more, but it’ll cost you more as well, experts say. CBC. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/ontario-s-new-blue-box-plan-will-recycle-more-but-it-ll-cost-you-more-as-well-experts-say-1.5768577

Faramarzi, H., & Drane, M. (n.d.) Introduction to operations management. Seneca College Pressbooks Network. https://pressbooks.senecacollege.ca/operationsmanagementintro/. Licensed for reuse under CC BY-NC-SA.

Faramarzi, H., & Drane, M. (n.d.) Upstream and downstream of a supply chain and its flow [Image]. Seneca College Pressbooks Network. https://pressbooks.senecacollege.ca/operationsmanagementintro/chapter/supply-chain/ Licensed for reuse under CC BY-NC-SA.

Guest Blogger. (2017, July 10). Reverse logistics 101. All Things Supply Chain. https://www.allthingssupplychain.com/reverse-logistics-101/

Nestlé. (2008, May 8). Nespresso expands aluminum recycling and reuse [Photograph]. Flickr. https://www.flickr.com/photos/nestle/16354467964. Licensed for reuse under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Riley, S.J. (2020, June 5) Ottawa is paying to clean up Alberta’s inactive wells. Are the oilsands next? The Narwhal. https://thenarwhal.ca/ottawa-paying-clean-up-albertas-inactive-wells-oilsands-next/

Scott, C. (Photographer). (2006, September 8). Coffee cup on desk [Photograph]. Flickr. https://www.flickr.com/photos/callumscott2/265229417/in/photolist-prnsZ. Licensed for reuse CC BY-NC 2.0

Supply Chain Canada. (2021). Who we are. SSC. https://www.supplychaincanada.com/about/who-we-are

Syverson, S. (2021, October 7). 45 Things you should know about reverse logistics. Warehouse Anywhere. https://www.warehouseanywhere.com/resources/45-things-about-reverse-logistics/

Figure 1.2 This figure shows a generic product supply chain flowchart: Raw materials selection then logistics (movement and storage, warehouses and bulk storage), then manufacture stage, then logistics (movement and storage, distribution centres and warehouses), to retail stores and/or consumers, then to product end use. [Back to Image]

Figure 1.3: This figure illustrates the upstream and downstream of a supply chain and its flows. In this chain, Tier 2 represents raw materials suppliers. Tier 1 represents the parts of the product made from those raw materials. They are then manufactured into products and distributed to retailers where customers, the end-consumer or users acquire them. This progression represents the forward flow of materials and/or goods indicated in Figure 1.3. Other “flows” include the flow of information that runs up and downstream, the flow of money which runs from downstream to upstream, and the reverse flow of materials when a product is returned to the manufacturer (E.g., if a product is damaged). Logistics, represented by the blue arrows that connect each tier and each step in the supply chain are required to manage all flows and movement in a supply chain. [Back to Image]

Figure 1.6: The first figure shows a linear economy following a traditional “take make- dispose” plan. Starting from the left to the right, there are Raw materials; Production; Use by the consumer; Disposable; Waste Pollution. This type of economy involves collecting raw materials and making them into products that will be used until they are discarded as waste. The second figure is reuse Economy is a reuse or recycling economy which includes collecting raw materials and transforming them into products. This economy is like a linear economy, the only difference is that some materials can be put back into the value stream and reused to manufacture new products or distribute more products.The third figure is Circular Economy which shows an alternative to Canada’s dominant linear economic model. From raw materials; Production; Use; Disposable to recycling. The circular economy looks at all options across the supply chain to use as few resources as possible and tries not to view garbage as waste but instead as a potential resource to be reused. [Back to Image]

Believe it or not, the typewriter was being used to prepare what we refer to today as a bill of lading 150 years ago. Technology evolved from the 1800s when the telegraph transmitted Morse code. Next came the telephone, then the radio. In 1950 computers entered the scene, and the internet surfaced in the 1990s. Today the Internet of Things, blockchain, GPS tracking, and the electronic transmission of data provide advanced technological advantages to the logistics industry. This chapter explores how technology is being used to improve logistics processes.

Tech Vision. (2020). Inside Amazon’s Smart Warehouse [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IMPbKVb8y8s.

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/logistics001oerfc/?p=22#h5p-4

The pandemic has highlighted the need for a robust supply chain, and one of the integral elements of an efficiently functioning supply network is the logistics link. In 2021, part shortages, backlogged ocean freight, closed borders, and driver shortages emphasized the importance of logistics in supply chain networks operating effectively. The logistics market in North America is estimated to expand to more than $12 trillion by 2023. (Bohdan, 2021) Logistics operators are looking to technology to gain operational advantages to meet the market demand. According to the Supply and Demand Chain Executive (Bodhan, 2021), six technological trends are leading the way in the transportation industry:

Although we will not be exploring all of the recent evolving technological trends, it is crucial to understand that technology adoption in the transportation industry is a dynamic process requiring agile management practices. When looking to technology for an operational advantage, we look to two areas of application: hardware applications and software applications.

Technology generally falls into one or more categories in the logistics world, as outlined in the table below.

| System Type | Description | Logistics Example |

|---|---|---|

| Office Automation | Helps to process business data, perform calculations and documents. | Spreadsheets, route planning software

|

| Communication | Provides supply chain visibility, freight visibility, facilitates sharing of information. | Virtual meetings, GPS, voice to text technology |

| Transaction Processing | Records BOL, stores transaction information. | EDI, Bar Codes, POS

|

| Management Information | Business analytics, Provides management info in real-time. | Logistics Information Systems |

| Decision Support | Software that enables simulation modes and analysis tools. | WMS, Data mining

|

| Enterprise | Creates and maintains data processing and integrates databases. | ERP systems |

The ultimate goal of technology in the Logistics Information Structure (LIS) is to provide real-time information to management. The LIS collects, analyzes, stores, retrieves, and disseminates data. It provides regular and customized reports. The sole purpose of all this data is to enable data-based decision-making. When failures occur in the supply chain, the first step is to find a solution to keep the freight moving. Once that is completed, root cause analysis routinely follows. One type of technology assisting in the root-cause analysis arena is blockchain technology.

The rise of blockchain technology provides solutions for dispute resolution, order tracking, and administrative efficiency.

“Blockchain technology is based on the concept of a distributed ledger. Instead of a centralized authority, power is distributed across participants on a network” (Shoukry, 2020).

According to Majaski (2021), a distributed ledger can be described as a ledger (collection of accounts or other financial information) of any transactions or contracts maintained in a decentralized form. It is a synchronized database accessible across different locations by a multitude of participants. This type of decentralized information is less prone to cyber attack, fraud, and other manipulation since there is no single point or central authority required. A distributed ledger is a record-keeping of everything that happens in a transaction, and it is stored in sequential order. The information is recorded as it happens and is stored by many participants. Since the ledger storage is decentralized, changing it is nearly impossible.

There are six steps in a typical blockchain transaction (PricewaterhouseCoopers, 2020):

Blockchain technology provides excellent opportunities for supply chains and logistics. Blockchain technology improves the traceability and visibility of freight along the supply chain. Processes can be automated, and any issues or bottlenecks can be seen, allowing participants to resolve the issue immediately (Ceulemans et al., 2020).

Blockchain operates within a network, and no one server holds the data. Instead, all the participants in the network each hold the data. This methodology empowers all network participants and prevents data from being altered. The data remains secure because it exists on many servers, not at a single point. This, in turn, improves data integrity and security. Blockchain is not yet universally adopted in the logistics community, but networks are being developed, and the interest in blockchain is gaining momentum.

Simplilearn. (2019, February 27). Blockchain in 7 minutes [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yubzJw0uiE4&t=2s.

Learn more about the potential impacts blockchain can have on logistics and the supply chain in this report from PricewaterhouseCoopers.

GPS technology allows fleet managers to track trucks, trailers, and drivers. Through Global Positioning Systems (GPS), companies can harvest real-time data and improve their supply chain visibility. However, GPS used in isolation limits a fleet manager. Companies need a complete Transportation Management System (TMS) to enable the use of GPS as an input into the logistics of the TMS. TMSs refer to the “category of software that deals with the planning and execution of the physical movement of goods across the supply chain” (Gartner, 2022). These systems focus on aspects of shipping like freight management, carrier rating, and route, mode, and carrier optimization (Essex and Kakade, n.d.).

Telematics is an interface that utilizes GPS, ELD- Electronic Logging Devices, IoT- Internet of Things, to integrate the data and aid in real-time supply chain monitoring. Through a telematics system, fleet managers can re-route drivers based on changing traffic trends, avoid accidents, monitor a driver’s attentiveness, find equipment, and be integral in routing autonomous vehicles.

The supply chain is only as efficient as the data driving it. With the development of new real-time supply chain data sources such as telematics, combined with an interpretative platform, supply chain managers are proactive and more responsive.

ELD is a technology that is significantly impacting the trucking world. A driver’s logbook was updated manually by the driver in the past. The driver would record all on-service hours, driving hours, rest hours, and waiting hours. The logbook is a required document used by Ministry of Transportation officials to validate driver compliance with legislated service hours. Most highway drivers are compensated based on miles driven, not hours of service, so it was not uncommon for drivers to manipulate their logbooks. If the driver could change a couple of entries to enable them to log more miles, they often would. The introduction of electronic logging devices has limited the ability of a driver to manipulate their hours of service. ELDs are becoming a federal requirement in many jurisdictions and driving compliance within the industry.

One element of the supply chain that can improve the utilization and efficiency of logistics is warehouse management. Effective warehouse management allows the logistics arm of the supply chain to function optimally.

Electronic Data Interchange (EDI) is the computer-to-computer exchange of business documents, such as purchase orders and invoices, in a standard electronic format between business partners, such as retailers and their suppliers, banks and their corporate clients, or car-makers and their parts suppliers.

EDI enables the companies to transfer the documents without having any people involved. The documents are automatically transferred from one computer (account) to another. As a result, there are many advantages to using EDI. The primary benefit is the speed and accuracy of the information transmitted. Information is made available in real-time and errors that may have previously been caused during the data entry process are eliminated.

Common information exchanged using EDI include:

Barcodes have been used extensively since the 1970s, and consist of data that is displayed in a machine-readable form that can be scanned by barcode readers. The information contained on the barcode is typically pricing information, product number and description and any other pertinent information. Barcodes have become the norm in retail operations allowing for pricing accuracy and easy price changes. This data provides point-of-sale information to allow retailers to track items being sold, update inventory, identify fast and slow-moving products and assist in forecasting.

Quick Response (known as QR) is using bar codes and EDI to make sales data available to vendors so that vendors can quickly replenish goods in the correct quantity. This is thought of as JIT in the retail industry. The goal is to reduce out-of-stock incidents, as well as use smaller more frequent deliveries to reduce inventory and operating expenses.

This technology uses radio waves to communicate the information contained on a tag attached to an object. The information contained on a tag may include things such as the product’s origin, date of production, shipment information, pricing info, and any other pertinent info. To transfer this info, both a tag and a reader are needed. There are two types of tags, active and passive. An active tag contains a power source such as a battery and can operate a great distance from the reader. Passive tags use energy from the reader. Unlike barcodes, the RFID tag and reader do not require a line of sight to transmit the information.

RFID applications include the following plus many more:

The complexity of the supply chain is rapidly increasing, and understanding how to integrate technology into logistics is crucial. The key takeaway from this chapter is the notion that a supply chain expert must stay abreast of current technology. More importantly, they must understand how to utilize the technology, put it to work; how to harness it.

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/logistics001oerfc/?p=22#h5p-3

Bohdan, A. (2021, March 31). Top 6 global logistic technology trends in 2021. Supply and Demand Chain Executive. https://www.sdcexec.com/transportation/article/21307643/amconsoft-top-6-global-logistic-technology-trends-in-2021.

Ceulemans, R., Diefenbach, T., & Guthmann, M. (2020). Blockchain in logistics. PwC. https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwittIjWhpb1AhUKXc0KHaX5BlAQFnoECAgQAQ&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.pwc.de%2Fde%2Fstrategie-organisation-prozesse-systeme%2Fblockchain-in-logistics.pdf&usg=AOvVaw2Wxnaf4X0-EWQfEj55BQuR [opens a PDF]

Essex, D., & Kakade, S. (n.d). Transportation management system (TMS). Tech Target. https://searcherp.techtarget.com/definition/transportation-management-system-TMS

Majaski, C. (2021, October 9). Financial technology and automated investing: Distributed ledgers. Investopedia. https://www.investopedia.com/terms/d/distributed-ledgers.asp

Section 2.9 was adapted from Chapter 7: Supply Chain Management from Introduction to Operations Management by Hamid Faramarzi and Mary Drane. Licensed for reuse under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Strong competition in the open transportation market has driven down profit margins. Even though the profit margin per move in logistics transportation is often slim, the volume of opportunities is great. This combination of low margin and high volume can maximize profits. In a low-margin environment, understanding and controlling costs is imperative.

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/logistics001oerfc/?p=52#h5p-5

Logistics cost is simply the total cost of moving freight from one location to another. The definition does not need to be complicated. However, depending on the mode of transportation, the Incoterms, headhaul and backhaul opportunities, figuring out how to allocate and control costs can be confusing. When purchasing logistics services either directly or through a third party, determining the purchase price results from both market supply and demand. As a logistics professional, the ability to maximize profits is determined by finding the balance between cost from a service provider’s perspective and price from the service purchaser’s perspective.

Depending on the mode of transportation, a logistics service provider (LSP) could be a trucking company, a shipping line, a railway, or an airline. This chapter will focus on trucking, also known as over-the-road transportation (OTR). Trucking, like all LSPs, has both fixed and variable costs. A key characteristic of the OTR industry is high variable costs and low fixed costs. The fact that roadways are funded through public revenues contributes significantly to the low fixed costs of the OTR industry. Approximately seventy percent of all costs in the OTR industry are variable costs and attributable to operational costs. (Atri & Murray, 2021)

Fixed costs in trucking are those expenses that will need to be paid regardless of whether or not the operation is hauling any freight. Examples of fixed and variable costs associated with trucking are listed in Table 3.1.

| Fixed | Variable |

|---|---|

| Equipment Lease costs (trucks, trailers,) | Labour (drivers) |

| Depreciation | Fuel |

| Office Leases or rent | Maintenance -parts and labour |

| Garage Leases or rent and/or Property tax | Roadway tolls |

| Interest on vehicles | Insurance, |

| Management costs (salaries) | LIcense, Registrations |

Fuel Surcharge

The cost of fuel is a significant variable cost for any OTR operation. In order to safeguard a motor carrier from operational losses caused by rising fuel costs, the industry has developed a Fuel Surcharge (FSC) formula to offset rising fuel costs. The premise behind the FSC is to pass along increasing fuel costs to the shipper. FSC is based on a peg rate and a national average of fuel costs per month. The difference between the peg rate and the national average diesel price is paid to the OTR carrier as an FSC. The FSC is added to the price of the freight move.

The Service Purchaser’s Perspective

A purchaser of logistics services is a company requiring freight to be transported from one location to another. Understanding the market rate for a move is imperative to operate an efficient supply chain. As a transportation service purchaser, the ideal outcome is to have goods delivered at the right time to the right location at the right price. Market factors such as supply and demand impact the price charged by OTR carriers. Truck driver supply dramatically affects the availability and price of OTR services. A buyer of logistics services needs to be in tune with crucial industry factors such as a truck driver shortage.

A new study into driver availability – Understanding the Truck Driver Supply and Demand Gap – was conducted by transportation consultants, CPCS. It updates the Canadian Trucking Alliance’s 2011 landmark report of the same name, which predicted a driver gap of up to 33,000 drivers by 2020: “the new study’s base case forecast calls for a shortage of 34,000 drivers by 2024 – reflecting an increase in demand of 25,000 and a decrease in supply of 9,000. The shortage could increase to 48,000 drivers based on plausible combinations of different trends that could affect industry demand, labour productivity and occupational attractiveness”(Canadian Trucking Alliance, 2016). Autonomous trucking technology can not come quick enough. An increase in OTR services is imminent and will be reflected in the availability and cost of consumer goods.

CNBC. (2019, April 13). How Amazon demand drives autonomous truck tech [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vMXivgUGVn8&t=204s.

Understanding how to price a transportation move is not as straightforward as it may seem. Several factors must be considered when establishing a pricing model. First, every driver has a maximum number of driving hours and a maximum number of on-duty hours set per day and per week. Federally regulated driver rest time is mandated. All driving and rest hours must be recorded and maintained in the driver’s logbook. In today’s trucking industry, many logbooks are maintained electronically. Strategic decisions regarding driver configuration and service hours need to be considered before setting a price for a transportation move. Preceding the driver configuration decision is the challenge of fully understanding each component of delivering freight. Underestimating how the components of a freight move fit together and how to allocate a cost to each segment could be the difference between operating profitably or the LSP losing money.

Let’s break down the elements of a move.

Figure 3.1

Elements of a Move Flowchart

From Adzija, 2020.

Pricing an Over-The-Road (OTR) Move

As a service provider, ensuring both the headhaul and backhaul costs are captured in the cost model can be a challenging task. The headhaul is the movement of freight to the delivery location from the freight pick-up location. The pricing of the headhaul move includes both the fixed and variable costs (see Table 3.1). It also needs to include driving miles, waiting time, loading/unloading time, and potential traffic congestion. One function of the route planning team is to review the likelihood of securing a paid backhaul load.

Backhaul is the return of the truck, trailer, and driver to the point of origin (terminal). If the freight contract stipulates that both the headhaul and backhaul legs of a move are included in the route, pricing each leg of the lane becomes easier. If, however, only the headhaul leg of the move is included in the contract, then it is up to the service provider to figure out a way to return the driver, trailer, and tractor to the point of origin of the load. To minimize lost revenue, trucking service providers will price backhaul loads aggressively. Often carriers will cost the fixed costs of a move in the headhaul and only price the variable costs in the backhaul move. Ideally, from the service providers’ perspective, the ability to return a load to the origination point by linking several headhaul moves would be most profitable, but this is not always achievable.

Cost Per Mile, Cost Per Pound, Cost Per Hour or a Combination?

Most often, full truckloads are priced on a rate-per-mile basis. The service provider needs to calculate a rate per mile for headhaul loads and a separate rate-per-mile for the backhaul portion. Frequently trucking companies will establish a required annual rate-per-mile that must be driven to break even. Equipment utilization and rate-per-mile have an inverse relationship. As equipment utilization increases and nears 100 percent, the required breakeven rate-per-mile decreases.

Less than truckload (LTL) pricing per load is based on either the weight of the freight, cubic size, or a combination of both. Often LTL loads include an element of load consolidation, and as such, computing the required cost per pound involves a material-handling element. Due to the complexity of coordinating the elements of an LTL shipment, the cost is higher than a full truckload shipment.

Charging an hourly rate for trucking is often associated with a shunting service or short PUD shipments.

Driver Configuration

Another decision point for the service provider is configuring the operator/driver component of a move. A single driver configuration occurs when one driver will complete the entire move from the point of origination, shipment pick up, delivery, and return. The single driver stays with the equipment for the duration of the move.

A slip seat move involves two or more operators. Each driver will operate the equipment for a set time interval – usually based upon the maximum allowable drive hours—and then a new driver will switch or relieve the previous driver.

Tandem or team drivers operate similarly to a slip seat move; however, both drivers stay with the equipment in a team driver approach. One driver rests in the cab while the other driver operates the truck in this configuration. Once driver A has exhausted their hours, driver B continues the route, and driver A rests in the cab or sleeper unit. An important note is that a tandem team is paid by the mile as a whole; each driver is not paid separately by the mile.

Route Planning

For a trucking company, effective route planning is critical. The ability to link headhaul and backhaul loads will maximize equipment utilization, revenue generation, and operator compensation. “If the wheels aren’t turnin’, no one is earnin'” applies here, meaning that freight needs to be moving from location to location loaded, minimizing deadhead miles so that a service provider can optimize revenue. The operation will lose revenue if a route has too many deadhead moves or inefficient slip seat driver exchange locations.

Fleet Management and Equipment Consideration

One element that a service purchaser underestimates is the trailer requirements of a service provider. Depending on the type of delivery agreement (drop and hook or live unload), the number of trailers required to fulfill a delivery requirement could fluctuate—the greater number of trailers required to service a customer, the greater the equipment cost. The greater the equipment cost, the greater the cost per mile charge required to break even. In a live unload/reload scenario, the driver remains attached to the truck. In this type of delivery, one trailer is sufficient to service the customer. However, if the contract calls for a drop and hook delivery, a minimum of two trailers are required to service the customer. If the contract also calls for dunnage delivery, the contract could require three or more trailers to service the contract.

Understanding Lanes

When a logistics provider is responding to a request for a quote or invited to provide a bid, the bid is often based on a delivery route, also known as a lane. A service purchaser often specifies the delivery lane requirements. For example, if an OEM requires a truckload of product picked up in Toronto, Ontario, Canada and delivered to London, Ontario, Canada, that would constitute a lane. The lane could be a return route or a single leg. A return route means that the service provider would be required to pick up in Toronto, deliver to London and return to Toronto – this could be classified as one complete turn. Assuming this is a live unload, let’s look closer at this lane.

The origination of the load is Toronto resulting in 1 hour to load the trailer. Delivery to London, Ontario is 2 hours. Freight unloading and dunnage reloaded will take 1 hour. The return trip to Toronto will take another 2 hours, and offloading the dunnage 1 hour. The route is completed.

The total time dedicated to the route is 7 hours with 4 hours of drive time.

Drivers have 11 hours of drive time available in a 14-hour time period (Ontario Ministry of Transportation, 2021). Equipment is available for use 24 hours per day. From a utilization perspective, this route would utilize a driver 36 percent (4hrs/11hours) of available drive time. The equipment is only 30 percent utilized (7 hours/24 hours). A driver utilization of 36% and equipment utilization of 30% is mediocre. The service provider would look to their route planning and fleet management team to add routes to this lane to maximize driver and equipment utilization. If the service provider cannot add additional lanes to this route, the cost per mile would need to be calculated based on the low utilization rates. Often low utilization will result in a cost-prohibitive bid.

Window Times

A window time is a pre-arranged appointment to deliver or pick up freight. Usually, a service provider only has a +/- 15 minute grace period to the window time. If the truck driver misses the assigned window time, they will need to wait until the supplier has dock availability. Waiting and delays are costly to a service provider. Missed window times can be caused by suppliers not having a receiving dock available at the prescribed window time. The service provider needs to establish a fee schedule for delayed dock availability.

Visit the American Transportation Research Institute and review the An Analysis of the Operational Costs of Trucking: 2021 Update [opens a PDF file].

The American Transportation Research Institute is a great resource and contains many trending trucking topics.

Establishing the cost of delivering freight contains many variables. Missing one of the variables could turn a potentially profitable lane into an unprofitable freight move. Data capturing technology is helping carriers analyze moves, highlight problem areas, and problem solve in real-time. Using all the tools available in today’s trucking industry is imperative if a company is to stay profitable.

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/logistics001oerfc/?p=52#h5p-6

Atri, L., & Murray, D. (2021, November 23). An analysis of the operational costs of trucking: 2021 update. American Transportation Research Institute. https://truckingresearch.org/2021/11/23/an-analysis-of-the-operational-costs-of-trucking-2021-update/

CNBC. (2019). How Amazon Demand Drives Autonomous Truck Tech [YouTube]. Retrieved December 21, 2021, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vMXivgUGVn8&t=204s.

Canadian Trucking Alliance. (2016, June 14). CTA study: Truck Driver Shortage Accelerating – Canadian Trucking Alliance. https://cantruck.ca/truck-driver-shortage-accelerating-according-to-new-cta-study/

Ontario Ministry of Transportation. (2021, May 9). The official Ministry of Transportation (MTO) truck handbook: Hours of service. https://www.ontario.ca/document/official-ministry-transportation-mto-truck-handbook/hours-service

Products need to move from one location to another location and doing that involves using a mode of transportation. Some common modes of transportation involve picking up products, using technology or using machines like trucks, boats, and airplanes to move products. Determining which of the modes of transportation to use depends on the product, urgency, and restrictions for moving that product.

A transportation restriction you may be familiar with is the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine that requires the vaccine to maintain a specific frozen temperature while in transit. Requirements for transportation include keeping thermal shipping containers filled with dry ice or alternate storage should shipping take longer than the expected three-day global delivery (Pfizer Incorporated, 2022). In addition, GPS-enabled thermal sensors are required to be returned to the manufacturer (Pfizer Incorporated, 2022). As you may remember, vaccines during this worldwide pandemic were required urgently all over the world. Consider the transportation logistics that were needed to manage this situation. This chapter will look at the different ways, modes, and determinations needed when transporting products.

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/logistics001oerfc/?p=55#h5p-7

Modes of transposition are the ways, methods, vehicles and machines used to move products from one location to another location. They are demonstrated in the image below as trains, trucks, and airplanes. An emerging transportation mode is the use of drones for delivery from airports (CTV Edmonton, 2021). Common modes of transportation to move products are trucks, trains, ships and airplanes.

Figure 4.1

Note. From Kukhta, 2021. [Image Description]

Considerations when determining which mode of transportation to use are deciding from the categories of shipping options that your product best fits. Common abbreviations and terminology that you need to know are:

In the context of this OER, bulk transport will refer to large quantities of products being shipped requiring ships, trains, or other modes of transport that handle such large quantities. Logistics Plus (2021) further explains the difference between these categories based on size and weight: “LTL shipments are smaller shipments typically ranging from 100 to 5,000 pounds. These smaller shipments will not fill an entire truck, leaving space for other small shipments. On the other hand, FTL shipments fill most to all of an entire truck and tend to be much larger, often weighing 20,000 pounds or more” (para. 2).

This explanatory video from Shipmate Fulfillment explains FTL, LTL and small parcel shipping:

Shipmate Fulfillment. (2020, May 12). Understanding logistics: Shipping in bulk, LTL, FTL and parcel explained [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/9p0grX0kDmg

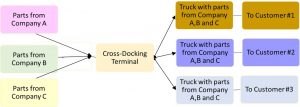

FedEx, UPS, and Purolator International are well-known, large logistics companies that move many products worldwide. The focus of courier companies like this is parcels and small packages that they consolidate (put together) into trucks that move them to warehouses or distribution centres, where they are split apart then re-assembled (consolidated a second time) then sent onto their next destination. An example might be small boxes of many types and colours of pens from different small manufacturers that are collected during a delivery route and sent to a distribution centre. From there, the boxes might be opened and broken apart so that the specific order for a number of pens and specific colours can be then assembled and sent out in a smaller package to a customer. It is very much like the use of LTL space in trucks. The FedEx, UPS, and Purolator International FTL or Full Truck Load websites have excellent and current information on logistics. Visit the following websites to find a lot of information and resources about their logistics practices.

Full Truck Loads (FTL), are used by companies that have enough product to fill one truck. This truck would take a dedicated load from the company directly to their customer. For example, automotive manufacturing supply chains use FTL loads primarily. A dedicated container of car parts shipped from a supplier to an assembly plant is a typical FTL shipment. Automotive suppliers have more than enough products to fill one truck so FTL is a good choice for them. It is reliable and secure because the product will go directly to its destination, without making multiple stops and being unloaded. The product won’t be damaged or have some of it go missing, because it stays on the truck and is not handled again until it is unloaded at its final destination. There are various examples of FTL companies, they include Old Dominion Truck Lines and Charger Logistics Inc.

Bulk in supply chain logistics refers to shipping products in large quantities that have not been split or packaged into smaller amounts. Some examples are raw materials required to manufacture products, agricultural commodities such as wheat, and other commodities such as Ore. Raw materials for agriculture and primary industries such as steel-making would ship in large amounts using trains, ships, and sometimes trucks to support shipping and delivery. An example of a company that can do bulk shipping is Twill, owned by Maersk.

This short video provides a definition of bulk shipping.

The Audiopedia. (2017, February 24). What is bulk cargo? What does bulk cargo mean? Bulk cargo meaning, definition & explanation [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/RdBq_NjbTOs. Licensed for reuse under CC BY.

This video from Intercargo provides statistics and other information on the shipping industry, a significant form of bulk transport. Did you know that over 12,000 bulk carrier ships are sailing the seas?

Intercargo. (2020, July 29). Dry bulk shipping: Sustainably serving the world’s essential needs. https://youtu.be/vfymGkcU77I.

You have been tasked to move a product. What do you have to consider? What information do you need in order to find the best way to move your product?

Suppose you have a huge pile of wheat to move from central Saskatchewan to Australia. In that case, you will have different considerations than if you are trying to ship live lobsters from Halifax to Winnipeg, Manitoba.

The first point of clarification is the use of the word ship. You may be wondering does this mean the mode of transportation is always a large sea vessel commonly known as a ship? No, the term ship/shipping in this context is being used as a verb and means to transport which may or may not be an actual sea vessel. If you want to ship or transport something, you will need to know: The physical description of the product, the route, destination and documentation required to transport the product. You may not be able to get all of the information but the more you have, the more you can increase your chances of planning and executing the movement of your product. Information like size and weight is very important to know. Other information may not seem as important but may be needed to ensure a successful and safe shipment. Consider using the following as a template for gathering information as you plan for shipment:

Shipping wheat from Saskatchewan to Australia

Moving a big pile of wheat from Saskatchewan to Australia would probably be done with trucks, a train to the coast, and then ship to Australia.

“Measure” for Wheat

How do you measure wheat? According to Debes (2015), “today, a bushel has a weight equivalent, different for every commodity. For wheat, one bushel equals 60 pounds of wheat or approximately one million wheat kernels. A common semi-truck grain hopper can hold approximately 1,000 bushels of wheat – or 60,000 pounds of wheat in a single load” (para. 3). A FedEx delivery van probably will not work.

Shipping Live Lobsters from Halifax, Nova Scotia to Winnipeg, Manitoba.

Shipping live lobsters from Halifax, Nova Scotia to Winnipeg, Manitoba could occur using a refrigerated truck, then air (lobster needs to be kept cold), then refrigerated truck again. Alternatively, you might use a dedicated refrigerated truck to drive directly from the lobster packing facility in Halifax to a restaurant in Winnipeg. You must take precautions to ensure that the lobsters arrive safely.

Once you have completed a product description, parameters, restrictions, and requirements related to packaging, moving, and storing the product, you can determine the mode or method of shipment. Multimodal and intermodal use two or more transport models, but with multimodal one transport company takes responsibility for the entire journey (one contract for the entire journey). Whereas, intermodal involves one contract for each transport company involved (multiple contracts) for the various stages/modes of the journey.

It is likely that at least one of these modes includes a transport truck. Since transport trucks are a common mode of transportation, a consideration to logistics in a supply chain is the number of qualified drivers available. It is possible that the shortage of qualified transport truck drivers may impact delivery times in a supply chain. In 2013, The Conference Board of Canada identified that the demands for qualified drivers would increase due to an ageing workforce and a need to find ways to attract new drivers would be important to solve this problem (Faramarzi & Drane, n.d). It is the standard practice that the product will remain in the same container during its journey on multiple modes of transport through the supply chain. Figure 4.2 looks at five common ways of moving products and shows a comparison of the standard modes of transportation.

Diagram Summarizing Various Modes of Transportation

Note. From Faramarzi & Drane (n.d.). CC BY-NC-SA. [Image Description]

There are many types of transport trucks used to move raw materials and products in a supply chain. The front of the truck is commonly referred to as a tractor or cab and couples (attaches) to different forms of trailers. The trailer is determined by the material or product that is being transported. The way in which a transport truck is referred to is often designated by the type of trailer that the tractor or cab is hauling. The following is an examination of some of the most common types of transport trucks and examples of what they transport.

Tanker trucks are used to transport fluids like oil, water, chemicals, and liquefied gasses. For example, gasoline from refineries to gas stations, edible vegetable oils to processing factories and bakeries, and raw milk to dairies. Figure 4.3 depicts a tanker truck that has a large tank as its trailer for holding and transporting liquids.

Figure 4.3

Maseru Industrial Water Tanks

Note. From Hogg, 2009. CC-BY-NC-SA

A flatbed truck can carry many products and as demonstrated in the image below the products are not covered. Flatbed trucks may be used to carry large oversized products or products that do not require protection. Considerations when using this mode of transportation may be permits and safety precautions. For example, a permit since the load being transported is larger than most vehicles, signage saying wide load, and even a safety vehicle escort letting other drivers know that the vehicle may be dangerous to pass and is moving slowly. Figure 4.4 depicts a truck pulling a low-profile trailer that is carrying an oversized and heavy load. Due to the size of this load, special permits and escort vehicles to ensure safety are required.

Figure 4.4

Kenworth

Note. From raymondclarkeimages, 2015. CC BY-NC 2.0.

Trucks with a refrigeration unit attached to the trailer, commonly referred to as a reefer, are used to deliver food products, medical supplies and chemicals requiring low temperatures to be safely transported. Figure 4.5 shows a refrigerated medium-sized truck used for delivering food that requires cold storage during transportation. You may remember in the introduction to this chapter we referenced the need to transport the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine in cold temperatures. A refrigerated truck was required. Learn more about refrigeration requirements in this document that contains a table with the temperature requirements for the commonly used COVID-19 vaccines.

Figure 4.5

Transport Truck Trapped Under Low Bridge

Note. From Scarborough, 2007. CC BY-SA 2.0

Dump trucks are rugged construction vehicles that can carry very heavy and hard-to-handle bulk material. Dump trucks are able to reach destinations such as rural areas, rough roads, and even into the backyards of people who live in the city. Dump trucks are used for carrying bulk raw materials like sand or gravel. Farmers often use dump trucks to carry bulk crops such as corn or soybeans in the supply chain as the crops are on their way to storage or processing.

This video shows a large truck dumping a load of gravel into a driveway.

Simonson, J. (2007, July 13). Gravel dump and dozer in Fairbanks, Alaska. https://youtu.be/daVXxnKE0W8. Licensed for reuse under CC BY.

What is a dumper?

“A dumper is a construction machine specifically designed to transport unconditioned materials (rubble, sand, earth). The dumper is a member of the earth-moving machine family. This equipment is usually equipped with 4 wheels with an open bucket in front of the driver. The dumper can tip and dump its load.” (Diallo, 2020, para. 1). This article discusses and shows different types of dumping vehicles.

Construction companies and service-orientated companies will typically use pick-up trucks to carry smaller products, packages, parts, and materials. Consumers at the end of the supply chain might use pick-up trucks to carry heavy items or to pull trailers full of products. Figure 4.7 depicts a pickup truck carrying supplies for police.

Figure 4.6

RGP Pick-Up Truck

Note. From Mitchell, 2011. CC BY 3.0

This CNBC article discusses how pick-up trucks dominate the United States automotive sales market: “led by trucks from the Detroit automakers, pickups accounted for five of the industry’s 10 best-selling vehicles in 2020 despite their increasingly higher prices and the coronavirus pandemic” (Wayland, 2021, para. 1).

Transporting by road can limit the size of loads carried due to various factors like low bridges, narrow roads, and roads not designed to carry the weight of heavy loads. If you are moving oversized products, you may need permits and plan your routes carefully. The image below from Perkins STC shows wires being lifted out of the way by utility workers to allow the truck to pass underneath safely.

Figure 4.7

Transport Truck Trapped Under Low Bridge

Note. From Scarborough, 2007. CC BY-SA 2.0.

Note. From Scarborough, 2007. CC BY-SA 2.0.

Perkins STC (2017), a company that can move large objects by road, discusses the challenges of moving these products: “the toughest dimension for us to plan, permit, and execute is height. Many of our loads easily reach signs, bridges, and wires and require more time to carefully attend to details associated with a high load. It’s not just finding a route under or around low bridges, it’s about mitigating height with the proper trailer and managing the support required from utility companies, bridge engineers, and railroad vendors in order to minimize the cost and schedule impacts for our customers” (para. 1).

Another mode of small package delivery is bicycle courier. This mode of transportation is excellent for food, parcels, documents, or anything else requiring short and fast journeys. Figure 4.8 shows an example of a Yandex bicycle courier carrying a package in a backpack.

Figure 4.8

Yandex Courier

Note. From Stolbovsky, 2021. CC BY-SA 3.0.

Transporting raw materials and goods by way of railroads commonly referred to as rail can be a very cost-effective way to transport long distances. Historically, it was cheaper to build railroads than it was to build roads. Canada and many parts of the world have extensive rail networks. If your factory or warehouse is located on a rail line, it is very convenient to move a lot of products via rail. Most automotive assembly factories have rail access to allow the efficient moving of their vehicles. In some cases, products have to be transported by truck to a place where the rail line can be accessed and then once at the destination, transferred from rail back to trucks for final delivery. Let’s examine some common types of ways to transport via rail:

Mixed freight as the name implies is a combination of different types of transport cars carrying a variety of cargo that may be raw materials and/or a variety of products. Gondola cars are typically open at the top but in the figure below the gondola cars have been covered. Figure 4.9 below, shows a freight train delivering a mix of covered gondola cars and cargo in boxcars. This type of train is very flexible and can carry a wide variety of products.

Figure 4.9

Class 50 mixed goods, July 1978

Note. From Lewis, 1978. CC BY 2.0.

Note. From Lewis, 1978. CC BY 2.0.

The demand for oil is exceeding pipeline capacity and as a result, more oil is being shipped by train even though it costs more (Walheimer, 2018). Many chemicals or liquids are moved one tanker car or a few tanker cars at a time. Trains that carry only crude oil over long distances can also be up to a kilometer long. Figure 4.10 shows a train carrying oil tanker cars.

Figure 4.10

Crude Oil Tanker

Note. From Parker, 2016. CC BY 2.0.

Note. From Parker, 2016. CC BY 2.0.

This article from Global News discusses how cancelling the build of an oil pipeline can shift logistics of moving oil to rail and ship: “oil will still ship but through rail. According to the federal government, as production of oil increased in Western Canada in 2018, it began to outpace pipeline capacity, meaning shipments of crude oil by rail increased to fill the gap, more than doubling from their 2017 levels.” (Dangerfield, 2021, para. 15)

Figure 4.11 shows A very long CN freight train traveling through the mountains carrying raw materials in hopper cars. This can be considered to be an intermodal delivery mode. A typical scenario would see cargo ships unload containers in a coastal port like Los Angeles, California, transfer them to a train that travels to Chicago, Illinois. In Chicago, the containers might be transferred to trucks for their final destination. The systems of these three different modes can safely and reliably be handled in the same types of shipping containers. According to Train Conductor Headquarters (2021), “a freight train length is anywhere between 140 feet [42 m] and 10,000 feet or 1.9 miles [3 km]. However, there were instances where a freight train has reached over 18,000 feet or 3.4 miles [5.4 km), pulling 295 cars” (para. 4). Read the full article.

Figure 4.11

Red and White Train on Rail Near Body of Water During Daytime