Showing Theory to Know Theory

Understanding social science concepts through illustrative vignettes

Volume 1

Edited by Patricia Ballamingie and David Szanto

Showing Theory Press | Ottawa, ON, Canada

2022

Edited by Patricia Ballamingie and David Szanto

Showing Theory Press | Ottawa, ON, Canada

2022

Showing Theory to Know Theory by Showing Theory Press is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

1

2

In The Elements of Style, Strunk and White famously implore us to show rather than tell what we want to express. In contrast, theoretical work seems perpetually prone to the latter. Nonetheless, abstraction and disciplinary jargon remain useful, synthesizing and communicating complex ideas—at least, to those who are already familiar with the terminology. This book aims to demystify theoretical concepts, making abstract-yet-valuable ideas more accessible by showing rather than telling how they are meaningful and usable in day-to-day situations.

Bringing together a collection of “illustrative vignettes,” Showing Theory to Know Theory aims to help students understand complex ideas without dumbing them down. Each vignette takes form in a different way: concrete, illustrative examples; short, evocative stories; reflexive and intimate poems; illustration, described photographs, and other audio-visual materials. Along with our dozens of contributors, we hope that this volume will be of use across disciplines and community contexts, democratizing theory while linking it to practical, grounded experience.

As a user of this book, it is important to remember that each vignette is not intended to be encyclopedic or exhaustive. Instead, in combination with classroom discussion, they aim to ground learners’ understanding of the term or concept in a specific example. Further nuance and interpretation will come from responding to the questions included with each vignette, completing exercises or additional readings, and having an instructor situate terms within their conceptual lineage.

Ultimately, after reading/viewing and discussing an individual vignette, our hope is that students will be able to articulate, in their own words, the meaning of the term or concept. We also imagine that this book will help learners form and describe connections between theoretical abstractions and concrete examples of how that abstraction is meaningful to lived experience. Eventually, they may identify or create their own vignette, based on an existing understanding of a theoretical concept or term, and draw connections to lived experience and concrete examples. In the long term, and as discussed later on (see Adopting this Book), the community of users around this book may choose to expand it into a larger, more comprehensive collection, mapping the broader relationships among social science disciplines and areas of study.

Overall, we aspire to help learners in both university and community contexts to make the all-important connections between theory and practice, the abstract and the concrete, the world of knowing and the realm of doing. Along the way, may they also develop the critical reading and thinking skills—as well as innovative forms of expression and representation—that are so urgently needed in today’s complex, entangled, and fraught social and political ecologies.

With gratitude,

Patricia Ballamingie and David Szanto

3

Vignettes are organized alphabetically by the name of the concept or term that the author addresses. While we originally considered a more curatorial approach to the book—for example, creating conceptual, methodological, or epistemic sections—we ultimately chose this more straightforward ordering. As a digital resource, and one that we imagine being used very differently by its different readers, we didn’t want to impose too much structure. That said, within given entries, we also link to other, related vignettes, where our editorial eye suggested such connection making.

Eventually, we hope to hear from our readers about different ways that they have organized the vignettes in their use of this book. We imagine that variable groupings will suggest themselves in ways that are relevant to their own learning needs. To this end, the Zotero-based search and filtering application on our website can help find the most pertinent entries. (Much thanks to University of Ottawa School of Information Studies master student, Swati Sood, for developing the Zotero library.)

Each vignette starts with a one-sentence description of the term or concept that is presented. We interpret these not as ‘definitions’ (since to define a complex term in a single sentence is generally problematic), but as simpler renderings of what follows in the author’s text. While the vignette provides a grounded illustration of the concept, the one-sentence description is more generalized. (Later, discussion questions and exercises may also open the reader up to a more general understanding of the term.)

Similarly, we have foregrounded the authors’ biographies, interests, and positionality to encourage critical reading of each vignette: knowing who (and sometimes why) a contributor has chosen a particular term and illustration is, we believe, important for readers to know in advance of reading the ensuing text. Theory is, after all, always interpreted! This is a key element of helping new learners understand how social science terminology is meaning in pluralistic ways.

Some vignettes involve visuals, some are entirely textual. Some offer abstract interpretations of the term or concept, some dive directly into a straightforward example. In some cases, conducting an exercise is part of ‘reading’ the vignette; often exercises or discussion questions, which follow the main body, will lead to further, hands-on learning about the term or concept.

Several vignettes include links to other entries, showing connectivity among themes and a relational geneaology of terms. Overall, we have attempted to keep references and citations to a minimum, both to encourage authors to maintain an accessible, generalized writing style and to help readers grasp key aspects of the text without extensive distraction. References and additional resources are nonetheless included with each vignette, to allow teachers and learners to explore the term further.

Our public-facing website, ShowingTheory.net, is one possible entry point into this book, although if you are reading this text, you have already started using the book!

The website offers a useful “filtering” tool based on the Showing Theory Zotero library. Searching for any keyword or term will return all entries in the book that may be relevant to your needs. It also provides a useful way of seeing which vignettes address similar themes, such as race, frameworks of knowledge, or methods in the social sciences.

The website also offers links to the PDF and EPUB versions of the book, which can be downloaded and used in an offline context. The web-based, HTML version of the book not only offers the most dynamic reading experience, but it also requires internet access, which we recognize is not universally available and accessible.

Showing Theory is also available as a print-on-demand textbook, and copies can be purchased from Ingram Spark. While there is a price associated with printed copies, it is solely to cover the Ingram Spark cost; no profit is returned to the publishers, editors, or authors. Please contact us for more details.

As is increasingly standard for high-quality, openly accessible educational resources (and as required by our funding agreement), Showing Theory is machine-readable and compliant with the Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act of 2005. All content is designed based on current Universal Design Standards, including alt-text for all graphics and proper text-to-background color ratio.

If, however, you find an issue related to accessibility, or other content that is either in error or problematic in your view, we encourage you to get in touch with us to report the problem. This can also include such minor issues as typos, formatting problems, or broken links. While the book has been extensively reviewed and proofread, mistakes always happen!

4

Beginning with Trish’s initial emails soliciting interest from colleagues, the response to this concept has been overwhelmingly positive. People immediately grasped the urgency for such a collection as “something we needed decades ago,” and recognized its potential value as a teaching resource. David replied immediately, with genuine enthusiasm. He saw it as a concept that had potential and value for a huge community of folks. Within a day he had put together a vignette and started having ideas for broadening the scope. Trish immediately knew she had found a collaborator.

Stars aligned and we discovered eCampusOntario’s Virtual Learning Strategy, through which we received the funding to make this project possible. A Government of Ontario–funded non-profit organization, eCampus works to develop and distribute online learning tools throughout the province. We also received administrative and instructional design support from Carleton University’s Teaching and Learning Services (TLS) team, who have been both expert guides and heartening cheerleaders. Sincere thanks to Valerie Critchley, Andrea Gorra, David Hornsby, Jaymie Koroluk, Patrick Lyons, Laura Ravelo Fuentes, Mathew Schatkowsky, and Dragana Polovina-Vukovic! We are also grateful to Nancy Snow (Associate Professor, Faculty of Design, OCAD University) for joining us as a Project Consultant, providing pedagogical and design input in the initial stages.

The eCampusOntario funding came with stringent reporting requirements and clearly delineated project deliverables, including adherence to accessibility standards and the use of a Creative Commons license. The latter is important to us as editors and contributors ourselves, because it will allow others to remix and repurpose the book’s content while ensuring that the original creators of each vignette are credited for their work and recognized as its originators. This, along with the book’s digital format(s) and free access, are key components of the open publishing ethos within which Showing Theory was conceived and created.

Publication of this open educational resource (OER), from conceptualization to scoping and team building, development, production, publication, and evaluation, took place over one calendar year, from start to finish, during a global pandemic. While it has not been a simple task, it is nonetheless testament to the power of collaboration and good will, to the flexibility and connectivity of digital tools, and to the promise that open-access publishing offers a new generation of learners.

5

In June and July 2021, we distributed our Call for Proposals (with guidelines, a submission template, and sample vignettes) to about 25 different scholarly association newsletters, listservs, and Facebook groups. Disciplines included: anthropology, art and design, critical education, environmental studies, equity studies, food studies, geography, sociology, political economy and political science. Contributions emerged from a broad range of social scientists and practitioners, with the majority coming from across Canada, followed by the United States, and United Kingdom. We are grateful for those that reached us from farther afield, providing additional perspectives and world views. These included submissions from Mexico, Finland, Greece, the Philippines, and New Zealand.

Our rigorous review process aimed at ensuring that the vignettes are as effective and accessible as possible, while also enabling authors to count them towards the narrow metric upon which academics are evaluated—peer-reviewed publications. An editorial review by both editors allowed us to move forward those submissions that fit within the critical social sciences, that were well developed, and that reflected the criteria we had established. Following an initial edit, each piece was sent to one scholarly reviewer with expertise around the given term or concept, and one community reader with similar perspectives but a less academic lens. This aimed at ensuring high-quality content that was also highly accessible to new learners. We are very grateful to our extended network of family, friends, and friends of friends, who served as community reviewers, both for accepting the challenge and offering their critical sensibilities!

In both review cases, reviewers remained anonymous, and their feedback was forwarded to the authors by the editors, often accompanied by additional comments and suggestions for revisions. The close-to-final drafts were then reviewed by one or both editors before moving on to copyediting and production. While it is common in some open publishing contexts to have both the authors and reviewers know each other’s identities (as opposed to the common convention in much academic publishing of conducting “double-blind” peer review), we opted for a more anonymous process here.

Our sincere thanks go out to the large and generous community of reviewers, both scholarly and community: Peter Andrée, Joan Andrew, Samphe Ballamingie, Kelly Bronson, Deborah Carruthers, Michael Classens, Lilly Cleary, Deborah Conners, Aviva Coopersmith, Stephanie Couey, Judith Crawley, Maria Dabboussy, Moe Garahan, Sherrill Johnson, Ali Kenefick, Meaghan Kenny, Irena Knezevic, Katalin Koller, Simon Laroche, Tess Macmillan, Florencia Marchetti, Nancy Marelli, Ajay Parasram, Namitha Rathinapillai, Tabitha Robin, Noah Schwartz, G Solorzano, Michelle Stewart, Kathy Stutchbury, George Szanto, Molly Touchie, Susan Tudin, Pamela Tudge, Annika Walsh, Bessa Whitmore, Amanda Wilson, Dana Zemel, and Trudi Zundel.

Additional thanks to our past and current students, who tested a wide sampling of vignettes and offered their opinions (and testimonials!) about what they read. This group of fearless learners includes: Brent Gauthier, Marie-Hélène Guay, Beatriz Lainez, Melissa Leam-Chen, Tony Horava, Matthew Montoni, Breena Johnson, Catherine Littlefield, and Iain Storosko.

6

Our hope is that this book will be of use across multiple contexts, including but not limited to university classrooms and other post-secondary learning environments. Given the increasing cross-disciplinarity of many fields, many vignettes are applicable and address themes from sociology to history, human ecology to epistemology.

Whether or not you use every entry in the book in your classroom (which would be surprising and impressive!), we encourage you to formally register your use of the book using our adoption form. This helps in several ways. First, it will allow us to stay in contact with you, if new or revised editions of Showing Theory are released. In the same way, you can maintain contact with us, to provide feedback on how the book is working for you, or to identify errors or omissions that need to be corrected in future editions. And, of course, knowing how many people are using the book—and where and in what contexts—is important feedback for us. It will help us keep making changes that address real needs, while also supporting future efforts to expand or evolve the project more broadly.

The use of “Volume 1” in our title signals our desire for this project to live and grow beyond its initial conceptualization. The current collection serves as a proof of concept, and we hope others will use it as a springboard to create other similar volumes (focused on thematic, disciplinary, or community-driven categories). We can imagine targeted calls for new volumes themed around Indigenous methodologies, critical race theory, political ecology, and many others. Our contributors covered a wide range of terms—some that we solicited, and some that were proposed through their own interest and expertise. Many concepts, however, remain unaddressed. In this way, we hope to spawn (potentially multi-lingual) future editions, remixes, and/or sub-volumes within other disciplines, fields, or faculties.

To that end, please note that Showing Theory is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC-SA license, the content in this book may be reused, remixed, repurposed, and maintained at will, provided that no commercial derivatives are created and that all future editions also carry the “share-alike” (SA) license. Any republication of the content, however, must follow Creative Commons terms.

7

In accordance with Carleton University, University of Ottawa, eCampusOntario, and the Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act (AODA), we have aimed to make this textbook accessible and available to everyone. To that end, Showing Theory to Know Theory was audited for accessibility by a team from the Carleton University Teaching and Learning Services unit. Their report served as the basis for a number of refinements and corrections.

The web version of Showing Theory is designed with accessibility in mind. It has been optimized for people who use screen-reader technology, and all content can be navigated using a keyboard. To the best of our ability, and within the parameters of the Pressbooks publishing platform, links, headings, tables, and images have been designed to work with screen readers.

In addition to the web version, this textbook is available in a number of file formats, including PDF, EPUB (for eReaders), HTML, and various editable files. You can also purchase print-on-demand copies from Ingram Spark. Please contact us for more details.

While we have tried to make sure that this textbook is as accessible and as usable as possible, there might still be some outstanding issues. If you are having problems accessing this resource, please contact us to let us know so we can fix the issue.

Please include the following information:

8

Patricia Ballamingie is a Professor in the Department of Geography & Environmental Studies and the Institute of Political Economy at Carleton University in Ottawa, Ontario. She has 20 years of experience teaching in the areas of human geography, environmental studies, political ecology and economy, and food studies. Since 2006, she has received seven prestigious teaching awards from a variety of sources, including her faculty, institution, student association, and city. Her program of research focuses on food policy and food systems governance. She served as Project Lead and Co-Editor of Showing Theory.

David Szanto is a freelance academic working across a number of institutions and within several roles. He has 15 years of teaching experience across food studies and communications, touching on the social sciences, humanities, art, and design. A former book editor and marketing-communications professional, he also brings 15 years of experience in the corporate and non-profit sectors. In addition to teaching, David works as a project manager, writer, and editor, and has extensive online and digital development experience. He served as Project Manager and Co-Editor of Showing Theory and is also Co-Editor of Food Studies: Matter, Meaning, Movement.

Philip Scepanski studies American television history and cultural theory. He has presented widely and published numerous articles and book chapters on topics related to television studies, collective trauma, and humor. His book, Tragedy Plus Time: National Trauma and Television Comedy, examines the way television’s most irreverent programming responds to our most serious moments.

Substances that we expel from the body tend to disgust us. Blood, mucus, feces, and urine come out of the body and are cast aside. Society treats certain people and groups similarly, casting them aside from the “social body.” The 1990s television comedy program In Living Color, for example, displayed these concepts with a character named Anton Jackson, played by Damon Wayans. An unhoused black man with substance use issues, Anton demonstrates abjection through both his body and social positioning. In one sketch from the show, he appears at an Army recruiting office, slurring his words and struggling to stand up straight. He picks his nose and wipes boogers on nearby objects. After his pants fall down and the recruiter complains about the smell, Anton refers to it as his “nerve gas.” While military service remains a path towards upward class mobility, he is too abject to follow this path into respectable society.

In most cases, scholars using the term abjection speak to two closely related aspects of the concept: bodily abjection and social abjection. Anton Jackson revels in the abjection of the things that would normally be cast off from the body: mucus, feces, urine, and so forth. These substances are bodily or physically abject. In the most significant essay on abjection, Julia Kristeva (1982) explains that abjection is important to our development as infants. Seeing matter move from being part of our body to being waste forces us to recognize that aspects of our body can become non-living. This, she argues, is important to learning about death. At the same time, many of the fluids that come out of the body—especially feces, blood, and mucus—carry bacteria and viruses, reinforcing associations between abjection, disease, and death. The revulsion we feel towards the abject is the result of both its literal role as disease-carrier and its more symbolic associations with death developed in early childhood. These theoretical understandings highlight that abjection is not simply about the thing that is cast off, it is part of a complex process of removal, through which the status and meaning of the abject change.

The meaning of symbols can be slippery, however, and these associations can easily transfer to other objects, including human beings. Kristeva speaks to the ways groups like women and ethnic and religious minorities bear associations with the abject.

In part because of his bodily abjection, Anton is “cast off” by society. He is socially abject in part because of his inability or refusal to fully remove the physically abject from close proximity to his body. In other In Living Color sketches, he often keeps his “bathroom”—a mason jar full of urine and a single floating turd—on his person. The Army recruiter’s unwillingness to engage with Anton marks the extent to which he cannot be incorporated into society. However, Anton bears other marks of social abjection, as an African American who is unhoused and shows signs of substance use. In various ways and to varying extents, these factors mark him as abject. Again, bearing direct associations with physical abjection, his apparent substance use may partly explain his smell, considering the inability of some users to control their bodily functions. At the same time, certain drugs, especially those involving needles, bring with them implications of diseases. More subtly, Anton’s race marks him as outside the dominant racial power bloc, further expressing his social abjection. However tempting it may be to understand the character as totally abject based on these societal factors, abjection is still a process. Anton was never fully abject, but he is continually re-cast off in moments like his attempt to join the army.

While abjection is used to consider the differences between one’s self and those things that are not the self, the relationship between self and other is complex. Anton keeps his abjection close to himself, finding humor in his own abjection. Similarly, we may keep the abject close to us in various ways, from the exchanging of bodily fluids during sex to keeping the ashes of a dead loved one on the mantle. Maggie Hennefeld and Nicholas Sammond (2020) point out that Western societies are increasingly “incorporating” the abject. That is, groups and individuals are finding ways to draw themselves near, once again, to those things and people that were once cast off. In part, this is reflected in media like In Living Color. Society has grown more comfortable with various gross-out strategies for entertainment in comedy, horror, and other genres. In other ways, efforts by various civil rights movements to gain acceptance within larger society are a sign that once-abject groups are in the process of more fully incorporating.

At the same time, members of dominant groups have attempted in recent years to portray themselves as abject, as evidenced by everything from mainstream conservative attacks on programs like affirmative action in the United States, to more marginal groups like proponents of “white replacement” conspiracy theorists. In this way, members of dominant cultures are incorporating abjection into their self-definition as a strategy to maintain power. Understanding the ways in which some groups are unjustly made abject while others unfairly claim abject status is thus a critical skill for understanding and changing the dynamics of power in contemporary society.

Discussion Questions

Additional Resources

Creed, B. (1986). Horror and the monstrous-feminine: An imaginary abjection. Screen 27, no. 1: 44–71.

Scott, D. (2011). Extravagant abjection: Blackness, power, and sexuality in the African American literary imagination. New York: New York University Press.

YouTube, “Anton Joins the Army,” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FsyZiwlbXd0&ab_channel=LourenBates

References

Hennefeld, M., and Sammond, N. (2020). Not it, or the abject objection. In Abjection Incorporated: Mediating the Politics of Pleasure and Violence, 1–31. Durham: Duke University Press.

Kristeva, J. (1982). Powers of horror: An essay on abjection. Translated by Leon S. Roudiez. New York: Columbia University Press.

Kathryn Fedchun is a PhD student in communication at Carleton University. She is a certified women’s counsellor and advocate who worked in the violence against women sector for a few years in Toronto, Ontario. She completed her master’s degree at the University of Ottawa in sociology and gender studies. Her thesis was a feminist autoethnography on the videogame League of Legends. She is currently a fellow at the Research on Comics, Con Events, and Transmedia Laboratory (RoCCET Lab) and is working on her second comprehensive examination on affect theory.

The image on screen slowly pans across a lush, rocky island. The sounds of strange wildlife surround the audience. Luke Skywalker stands on the edge of a cliff. Persuaded by Rey to teach her the ways of the Force, Luke asks her to sit on a rock with her legs crossed. Luke explains, “the Force is not a power you have. It’s the energy between all things, a tension, a balance that binds the universe together” (Johnson, 2017, 48:10). He asks Rey to close her eyes and breathe. Small tendrils of Rey’s hair sway in the wind as she closes her eyes and breathes in. Music begins as Luke takes her hand and places it firmly beside her on a rock.

Luke: Now, reach out. Breathe. Just breathe. Reach out with your feelings. What do you see?

Rey: The island. Life. Death and decay. That feeds new life. Warmth. Cold. Peace. Violence.

Luke: In between it all?

Rey: Balance. An energy. A Force.

Luke: And inside you?

Rey: Inside me… That same Force.(Johnson, 2017, 48:25)

When Rey begins to describe what she sees, the audience is invited into her mind: wildflowers blow in the wind signifying life; fossils underground represent death and decay; new life grows in the form of small seedlings; the warmth of the sun shines on the cliff; the cold waves crash into the shore. A porg (a fictional bird featured in the series) shelters her newborn babies under her wing, symbolizing peace. Then we see violence: a porg nest with broken eggs gets washed away by a large wave. According to Melissa Gregg and Gregory J. Seigworth, “affect more often transpires within and across… all the miniscule or molecular events of the unnoticed” (2010, p. 2). In this scene, seemingly insignificant events on the island are only noticed because Rey allows herself to feel them, to be affected by them, through the Force. Luke asks Rey what is between life and death, cold and warmth, peace and violence. Rey explains that between it all is a Force.

Like the Force in Star Wars, affect “arises in the midst of in-between-ness… [it] is in many ways synonymous with force or forces of encounter” (Seigworth and Gregg, 2010, p. 1–2). This powerful Force, or energy, exists inside of Rey. By reaching out with her feelings, Rey senses that all things are connected through the Force. Similarly, the power of affect exists inside of us: “a body’s capacity to affect and to be affected” (Seigworth and Gregg, 2010, p. 2).

Of course, affect exists beyond the fictional world of Star Wars and Jedi powers. It is often considered synonymous with emotion or feeling. For example, one could use affect theory to study the emotional impact of ending a romantic relationship. Yet affect is both more and less than emotion and feeling… it is an almost unnameable sense of bodily or visceral impact that arises without direct physical contact. Affect is all around us: between objects, between feelings, between ways of being.

Affect theory emphasizes the causes and impacts of affect, and everything in-between. There is no single definition that perfectly encompasses affect; as a mode of theorizing, affect is always in flux (Seigworth and Gregg, 2010, p. 3). Scholars are fascinated by affect and use affect theory to critically investigate depression (Cvetkovich, 2012), happiness (Ahmed, 2010), cruel optimism (Berlant, 2011), ugly feelings (Ngai, 2005), video games (Anable, 2018), ordinary affects (Steward, 2007), and touch (Sedgwick, 2002).

In Star Wars, the Force connects everything across the galaxy. Similarly, affect theory helps us explore our connection with the world around us. Evidently, the force is with you.

Discussion Questions

References

Ahmed, S. (2004). The cultural politics of emotion. Edinburgh University Press.

Ahmed, S. (2010). The promise of happiness. Duke University Press.

Anable, A. (2018). Playing with feelings: Video games and affect. University of Minnesota Press.

Berlant, L. (2011). Cruel optimism. Duke University Press.

Cvetkovich, A. (2012). Depression: A public feeling. Duke University Press.

Gregg, M. and Seigworth, G. J. (Eds.). (2010). The affect theory reader. Duke University Press.

Johnson, R. (Director). (2017). Star Wars: The Last Jedi (episode VIII) [Film]. Lucasfilm Ltd.

Massumi, B. (2002). Parables for the virtual: Movement, affect, sensation. Duke University Press.

Massumi, B. (2015). Politics of affect. University of Minnesota Press.

Ngai, S. (2005). Ugly feelings. Harvard University Press.

Sedgwick, E. K. (2003). Touching feeling: Affect, pedagogy, performativity. Duke University Press.

Stewart, K. (2007). Ordinary affects. Duke University Press.

Miho Trudeau is a PhD Candidate with the School of Architecture, Planning and Landscape at the University of Calgary. Her doctoral research explores people’s experiences with the development and usage of natural playgrounds in Calgary, Alberta.

The different ways that an environment, or an element within an environment, can be used are called affordances. For instance, if there is a declining flat surface in an environment, such as a ramp, that environment has a rolling affordance. What we are able to experience in an environment is dependent on both it and us, the user. For example, a bench of a certain height could be used to sit on or hide beneath; however, the ability to do these actions is also dependent on the individual. A very high bench may not allow a small child to sit on it, while a taller person may not be able to hide beneath it. Moreover, social and cultural contexts may affect how a person uses a bench. For example, although a person may wish to jump and walk on a bench, social norms may deem this as unacceptable behaviour, which may inhibit the bench from being used in that way. In this way, affordances are dependent on the environment, the user, and other contextual socio-cultural factors.

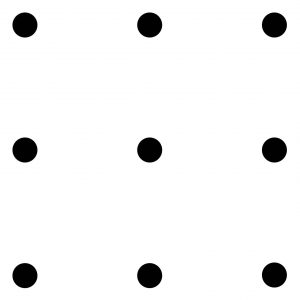

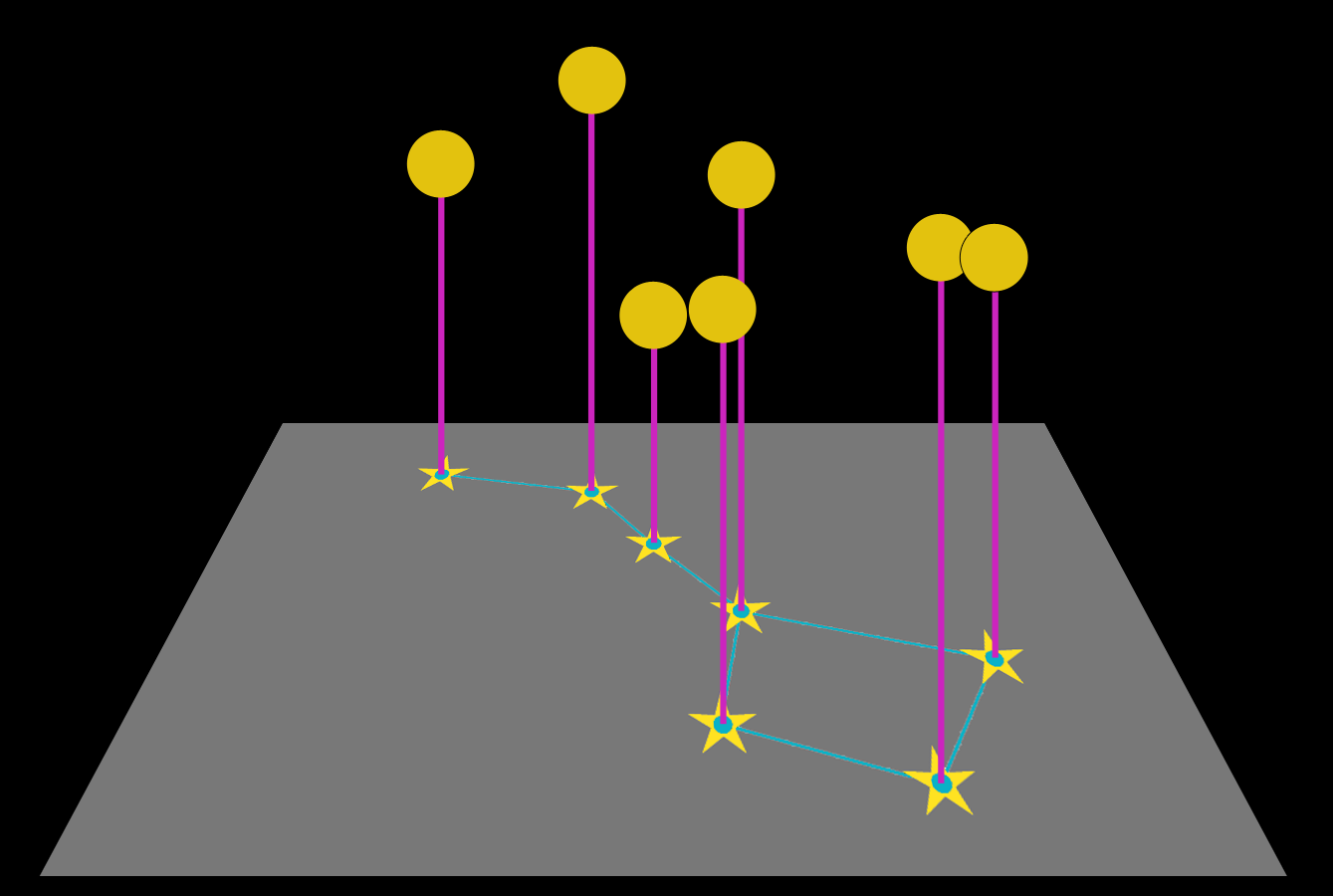

Children’s play environments, such as playgrounds, are often assessed for the different affordances that they offer children. Rather than looking at the different structures within a playground, sites can be analyzed for the different use functions, or affordances, present within the site. For example, a site can be analyzed for physical affordances (e.g., climbing, jumping), social affordances (e.g., cooperative play opportunities), creative and constructive play affordances (e.g., building with sand or other loose materials), and others—the list goes on and on. Below is an example of a playground that is annotated with diverse affordances offered to users. Note that these annotated affordances are dependent on a user’s subjectivity; for example, if a playground has a climbing structure, climbing is only available as an affordance for those with that physical capability. When considering the affordances within a site such as a playground, it is important to consider who the users are and how contextual factors may also have an impact. For example, what are the affordances of a playground such as this if the primary users have physical disabilities or if the playground is situated within a community with high crime and vandalism rates?

Perception is also a significant factor within affordances. How a user perceives an affordance within an environment will affect the actualization of the affordance, that is whether the perceived use function is carried out by a user. For example, within the playground, the slide and the rope ladder are relatively easy to perceive by most users, meaning that they will likely become actualized affordances. Other structures, such as the rock boulders, are less evident in their potential use, and might be used for sitting or for more active play, such as jumping or climbing. Given their ambiguity, less structured affordances invite more diverse interpretations, enabling children to feel more comfortable playing on them than, for example, on a bench. Similarly, affordances that allow for diverse interpretations may lead caregivers to feel more comfortable than, for example, sitting inside a play space or on a clearly demarcated play structure such as a climber.

Discussion Questions

Exercise

Visit a nearby public space and take a photo. Try to ensure that your photo does not include identifiable people who may not want to be photographed. You can also blur people’s faces afterwards to protect their anonymity. Observe and note the site’s usage for a short period of time. Later, annotate the photo with the observed and potential affordances of the site.

Additional Readings

Chemero, A. (2003). An outline of a theory of affordances. Ecological Psychology 15 (2): 181–95.

Gibson, J. J. (1979). The ecological approach to visual perception. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Heft, H. (1988). Affordances of children’s environments: A functional approach to environmental description. Children’s Environments Quarterly 5 (3): 29–37.

Kyttä, M. (2004). The extent of children’s independent mobility and the number of actualized affordances as criteria for child-friendly environments. Journal of Environmental Psychology 24 (2): 179–98.

Maier, J.R.A.,Fadel, G.M., and Battisto, D.G. (2009). An affordance-based approach to architectural theory, design, and practice. Design Studies 30 (4): 393–414.

Norman, D. A. (1999). Affordance, conventions, and design. Interactions 6 (3): 38–43.

Norman, D.A. (2013). The design of everyday things. New York: Basic Books; Revised and expanded edition.

Rietveld, E., and Kiverstein, J. (2014). A rich landscape of affordances. Ecological Psychology 26 (4): 325–52.

Udacity. Definition: Affordance – Intro to the Design of Everyday Things https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a6F0EYCUjcE

Katalin Doiron-Koller is an Acadian-Hungarian woman, critical political ecologist, and non-profit professional living as a guest in unceded Wolastoqey territory. Her research on allyship is situated at the intersection of relationality, environmental justice, and the politics of reconciliation.

Learning to centre Wabanaki peoples and their knowledges, languages, and lived experiences toward decolonizing education in New Brunswick has been the most rewarding journey of my life. As a non-Indigenous activist-scholar and a Project Manager working with and for Wabanaki communities, I have sometimes been referred to by Wabanaki friends and colleagues as an ally. While I am honoured by this title, I feel a significant duty and responsibility to model the values and behaviours necessary to reciprocate the spirit of the Peace and Friendship Treaties, the original covenants between Wabanaki peoples and European colonists that committed all nations to living together peacefully in Wabanakek. Everyone living and working in this place are beholden to the Treaties, whether descended from settlers, arriving as newcomers from other lands, or carrying the ancestral knowledge of Wabanaki nations. This means we all have a responsibility to one another, our ancestors, future generations, and this land, and to coexist in harmony and mutual respect. This way of being in relationship means living by an ethic of personal and collective relational accountability to each other and the land, in gratitude for the reciprocal friendship and support we enjoy (see Wilson, 2008).

On an individual level, I personally feel accountable to Wolastoqewi Kci-Sakom spasaqsit possesom (Wolastoq Grand Chief Ron Tremblay, morning star burning), who has taught me that as a non-Indigenous ally, it is my job to educate my own (non-Indigenous) people, and to model what it means in contemporary times to be a Peace and Friendship Treaty person. It is an arduous process to understand how best one can live this way, and even more so to model and share with others what is inherently an existential, inwardly reflective, personal process of decolonizing the way one thinks, acts, and interacts in the world. In truth, becoming an ally and living as a Treaty person can be an immensely uncomfortable journey, but it is positively life changing and deeply transformative (McGloin, 2015). As with many things that result in personal growth, if you don’t experience discomfort, you’re probably not doing it right!

In my research on allyship in Wabanakek, many non-Indigenous people have likewise confessed the discomfort they feel when confronting their own colonial ideologies and preconceived notions to allow for an anti-colonial perspective to propagate. Indeed, learning to decolonize one’s mind is a core element of learning to live in allyship with the first peoples of the land you inhabit. ‘White guilt’, a common feeling that non-Indigenous White people experience when learning the truth of the role their ancestors played in supporting the Residential and Day School System or other violently genocidal Canadian policies, such as the Sixties Scoop, malnutrition testing on undernourished Residential School students, and reproductive sterilization of Indigenous women without their consent, among others. Learning the truth of this dark history and ongoing neocolonialism on Turtle Island is a crucial first step toward becoming an ally and a necessary prerequisite to taking actions that decolonize social norms, discourses, and behaviours (Manuel & Derrickson 2015).

Non-Indigenous people can also experience the discomfort of decolonizing the mind when encountering Indigenous temporalities, referred to by Indigenous scholars as “relational time” (Pickering 2004). Relational time is not based on a western clock, nor is it defined by seconds, minutes, hours, days, weeks, or months. Rather, relational time is centred on building relationships, allowing the life cycles of the natural world to guide human activities, rather than a corporate clock buzzing us through a capitalist work-life balance (or lack thereof) (Pickering 2004). From the perspective of relational time, no minute is wasted on conversation or waiting or rest. All things happen when they are meant to happen, and the time it takes to get there is part of the journey. Yet, even after a decade of working as a Project Manager with Three Nations Education Group Inc. (TNEGI) and being aware of this myself, I am still learning to slow down and appreciate just being in relationship with others and the natural world, for this way of being is critical to becoming in allyship with the first peoples of the land.

As an example of this discomfort and allied becoming in practice, when TNEGI educators began requesting training from a non-Indigenous organization to help them harness their ancestral memory for land-based learning, I knew it was my responsibility to ensure the training was situated in relational accountability with Wabanakek. In other words, a decolonial, land-based education must be led by the first peoples of that land, be founded on their protocols and values, and be situated in the context of relationship to Mother Earth and all human and non-human beings within it. Given this, I approached our non-Indigenous partners and proposed we adopt a generative, relational methodology for the training that would hold space for and encourage an anti-colonial, Indigenous ethic to emerge and guide the learning process (Koller & Rasmussen, 2021).

Even though the goal was to let the training direction be generated by the participants, when the first day began, I found myself obsessed with schedules and timeframes and making sure everything followed a predesigned schedule. TNEGI had spent a lot of money on the initiative and, if successful, it could help decolonize the way training was conducted across Canada. So when the first day’s agenda ran late because we had spent a lot of time getting to know one another and telling stories of the history of Esgenoopetitj, I began to feel an intense anxiety that we would fall behind and the value of the training would be reduced.

I was feeling the weight of the world on my shoulders, and when the day finally ended, I escaped to the ocean. The movement of the water always makes me feel better, reminding me with its immense energy that I am just a small part of a larger, dynamic world. It was a beach of rugged sands and whitecapped waves. I began to feel reinvigorated and walked along, my frustrations about the day spinning in my head.

Scanning the sand, I noticed the presence of smooth rocks with cylindrical holes. Being nearby fishing communities, I rationalized that these must be some element of a fishing apparatus, yet I had never seen anything like them. I sat down, cradling a dozen of these unique formations on my lap. As I stared out over the timeless, constant movement of the water—up and down, in and out—I was overcome by a feeling of finite presence on this planet and, surprisingly, a feeling of coming home that I had never felt in any place else.

I recalled the stories Mi’kmaq knowledge holder Bobby Sylliboy had shared with us that day, about how the Mi’kmaq people of the territory had sheltered Acadians that were being hunted by the British during the expulsion of 1755. Everyone had been in awe of Bobby’s stories; the experience sparked a bond between us as we unpacked his teachings and reflected on how the past had shaped present-day society. I realized I had actually learned a great deal during our day on the land, not only about my Acadian ancestors and their unique relationship with the Mi’kmaq, but also about myself and where I came from, about the subjectivity of truth, and about the strategic alliances that made up our shared past and that could inform our shared future (Davis, O’Donnell & Shpuniarsky 2007).

Recognizing my privilege as an Acadian descendent in Mi’kmaq territory, I was able to reflect on my discomfort from the day’s events and realize how unreasonable and rigid I was being. It became clear to me that the real value of learning on and with the land is the holding of space where teachings can arise by being in relationship with the land itself; moreover, building relationships takes time. In other words, my discomfort had been a reaction to experiencing relational time when I was so used to colonial time. Were I to let go of the expectation for a perfectly timed sequence of events, I might relax enough to experience the value of the day—for creating the space to allow our relationships with one another and the land to grow.

The entire experience left me feeling better prepared to undertake my obligations as a Peace and Friendship Treaty person accountable to my Wabanaki and non-human relations. Decolonizing how we embody concepts of time is part of becoming an ally and living by the principle of relational accountability (Wilson 2008). To live relationally requires a presence of mind, body, and spirit that only exists outside of colonial time. Decolonizing how we embody time means slowing down and focusing on that which is most important for the betterment of the human and natural world—our relationship to one another and the land. It means being grounded in space and time, while allowing our respect and recognition of each other’s agency and our non-human relations to guide our behaviours in this shared place. This is a teaching I will never forget.

The next day, as I combed the shoreline with some teachers, I stumbled across another of the stones with a hole through it. I called Stacy Jones and Fran Dedam over and shared my discovery. They stared wide-eyed. “Pukulatmuj!” they said. They explained that Mi’kmaq stone spirits—known as Pukulatmuj—are tricksters that hide when they see humans. But when they are attracted to a person’s aura, they follow them, hiding behind rocks while peering out through a hole in the stone. Finding these special rocks is a sign Pukulatmuj have been following you because your spirit is shining bright. We had a laugh when I told them how many of these rocks I had encountered the night before! Not only did I feel specially chosen by Pukulatmuj, but in their telling me this story, I felt a genuine welcoming and belonging. As an ally, I knew I must honour this trust in reciprocity, carrying the teachings I had received to bring awareness to others in our mutual vision for a decolonized future.

Discussion Questions

References

Davis, L., O’Donnell, V., & Shpuniarsky, H. (2007). Aboriginal-social justice alliances: Understanding the landscape of relationships through the Coalition for a Public Inquiry into Ipperwash. International Journal of Canadian Studies, 36, 95-119.

Koller, K.D., & Rasmussen, K. (2021). Generative learning and the making of ethical space: Indigenizing forest school teacher training in Wabanakik. Engaged Scholar Journal: Community-Engaged Research, Teaching, and Learning, 7(1), 219-229. doi: https://doi.org/10.15402/esj.v7i1.70065

Manuel, A., & Derrickson, G. M. (2015). Unsettling Canada: A National Wake-up Call. Toronto: Between the Lines.

McGloin, C. (2015). Listening to hear: Critical allies in Indigenous studies. Australian Journal of Adult Learning, 55(2), 267-282.

Pickering, K. (2004). Decolonizing time regimes: Lakota conceptions of work, economy, and society. American Anthropologist, 106(1), 85-97.

Wilson, S. (2008). Research Is Ceremony: Indigenous Research Methods. Black Point: Fernwood Publishing.

Yael Cameron Klangwisan is a senior lecturer in education at the Auckland University of Technology. Her research interests are interdisciplinary, spanning education, poetics, and religious studies, and connected by a focus on critical theory. She has published widely in these areas.

The original epic of Oedipus and the Sphinx is a lost poem. This is itself a fascinating feature of the legend. We do not even have the entire telling of it. We only have what amounts to little pieces of a greater mosaic. In this telling, our scene takes place in the desert near Thebes, in Ancient Greece. There are two characters here, protagonist and antagonist, and at the moment of meeting the desert peels away until we are left with only these two, face to face.

In the first of the two figures, we have Oedipus. Raven-haired Oedipus is a young man of mysterious origins. He does not know where he comes from or who he is. This question of identity hangs over his head and troubles him. He is a young man, a handsome one, and a hero. He is a man who yearns to prove himself. He is desperate to become someone. Thus, he has come into the desert to confront the Theban Sphinx and win or die in the attempt.

The other figure in the tale is the Sphinx, a monstrous creature with a woman’s face. It is with some irony that we know, according to Apollodorus exactly, where she comes from and who she is. Sphinx is the daughter of two unnatural, serpentine creatures: Echidna and Typhon (or, according to Hesiod, Orthus, the three-headed dog). Sphinx has the face of a woman, but the body of a lion and the wings of an eagle. In this tale she is alone and dangerous in the desert, having wreaked havoc on Thebes, slaughtering its young men.

On the Attic Kylix above, we see the moment of meeting captured by the Painter of Oedipus. Oedipus sits below, with the Sphinx on the pedestal above him. They are frozen in time. Face to face, their gazes lock onto each other. Oedipus’s gaze is on this creature. He is recognisably human, a man, one of us. The lonely Sphinx is Other. She is the product of a ghastly union between horrors. She is a terrifying amalgamation of human and animal parts. She is altogether strange. Oedipus becomes more man than ever before in this moment of locking gazes with the Sphinx. Oedipus finally becomes a subject in the mirror of the Sphinx’s gaze.

The Sphinx has a riddle that she learned from the muses. She sings to Oedipus, “What is that which has one voice and yet becomes four-footed and two-footed and three-footed?” This is a pertinent riddle for canny Oedipus, and he works it out immediately. “A man,” he replies, because the riddle is the sum of his own life story. He is the one that has one voice, he once crawled on all fours, he now stands on two feet, and one day he will have to lean on his staff as an old man. This is who he is.

The Sphinx, defeated, dies on the spot. In one retelling she hurls herself from the citadel, and in another retelling, it is Oedipus who runs her through with his weapon. This tale is one way to explore the concept of Alterity. Alterity is, at its core, a relationship between Self and Other, where difference plays a defining role. What is understood as the Self crystallises in this moment.

Discussion Questions

Exercise

Watch the scene, “The Council of Elrond” from the film, The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring. How do the author J.R.R. Tolkien and the filmmaker Peter Jackson present alterity in the encounters between races and peoples of Middle Earth? How does alterity figure as a feature of the Fellowship?

Additional Resources

Apollodorus. (1998). The library of Athens. Oxford World Classics.

Levinas, E. (1999). Alterity and transcendence. Columbia University Press.

Renger, A. (2013). Oedipus and the Sphinx. University of Chicago Press.

Sophocles. (1991). Sophocles: The complete Greek tragedies. University of Chicago Press.

Vaccaro, C., & Kisor, Y. (2017). Tolkien and alterity. Palgrave McMillan.

Chelsea Russell is a PhD student at York University in the Communications and Culture Program. Her dissertation research analyzes female robots in videogames by focusing on feminist and affectual practices and questions of the posthuman. Currently, she is a SSHRC-funded research assistant on young people, digital capitalism, and the videogame platform Roblox.

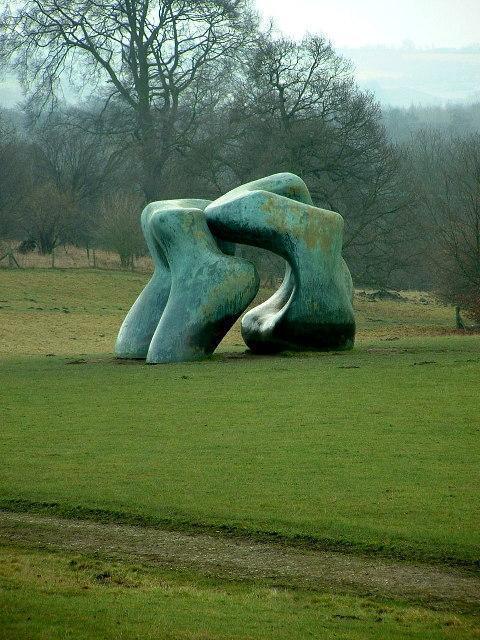

The painting below illustrates a significant connection between the technological and the environmental. It shows the figure of Gaia (Mother Nature) stripped down to reveal an (almost) infectious technology within. The physical world of technology is depicted as solidly within Gaia. Notably, the figuration of Gaia is as a white woman, which follows from much of the discourse around the Anthropocene that portrays it as “undeniably white” (Todd 2015, p. 246). This image therefore encapsulates that whiteness in order to highlight the political approach to understanding crises evoked within the Anthropocene.

Another aspect of the painting is the technological intervention within her body. Gaia is subjected to the whims of technology, while also being modeled after the goddess of love, Venus, in Sandro Botticelli’s famous painting, The Birth of Venus. The contrast between Gaia-as-Venus and 21st-century technology dramatizes the relationship humans have with both the past and the future. In bringing attention to both Whiteness and the technology within Gaia, this image is intended to evoke a sense of relationship to Earth but also to humanity’s own conceptions of Earth. The anxiety of the Anthropocene is what is on display here. To understand the Anthropocene fully, however, it is important to consider the history of thinking that has led to its current conception and to the future of the ways we can understand it.

The word Anthropocene can be broken down into its etymological parts: anthropo, which refers to “human,” and -cene, which relates to “epoch” or “geological time” (Ellis, 2013). The term thus invokes a moment in time in which human invention, enhancements, and actions have resulted in a massive shift in earth’s ecology. Human intervention has affected the fundamental processes of nature and the natural order—especially those of non-humans. Despite the “abundance of evidence” that the Anthropocene has been established as an epoch, the concept continues to be rejected and considered controversial among politicians, scientists, and climatologists (Ellis, 2018, p. 25). This debate is largely couched in whether Earth has left the prior epoch—the Holocene. Nevertheless, human-based alterations to the Earth’s ecology, biology, and climate are undeniable.

Ecologist Eugene Stoermer and chemist Paul Crutzen neologized (created) the term Anthropocene in the 1980s. It was originally used to describe large-scale human activities that dominate earth’s climate and biodiversity (Grusin, 2017, p. vii-viii). Although the term was coined only a few decades ago, it characterizes intense human impact upon ecological, geological, and biochemical processes. The history of conceptual Anthropocentrism emerged alongside the processes of capitalism, industrialisation, and the proliferation of nuclear power (Grusin, 2017, p .1), bringing unprecedented climate change, ecological disruption, economic growth, and technological booms. These shifts in human activity imposed disproportionate human pressures on the Earth that would not have happened otherwise.

The Anthropocene has found its way into popular discourse and culture. Public response to increasing ecosystem instabilitycan be seen through the #FridaysforFuture hashtag, the Green New Deal, and, in 2021, an update to the World Scientists’ Warning to Humanity. Through these examples and others, we are coming to understand that negative environmental change affect both non-human and human beings.

The industrialization and technologizing of humanity can be understood as “a dominant factor shaping the Earth and its associated life-supporting systems” (Steffen, Crutzen & McNeill, 2007, p. 614). In other words, the impacts of the Anthropocene on both society and the Earth, are interrelated. Moreover, as the digital and industrial economies surge, the need for technological parts increases, and with it comes an increase in demand for efficiency. This cycle is contingent on the raw materials needed for such practices, further accelerating the impact on Gaia as we continuously attempt to produce greater economic value.

Human/non-human relationships have long been made into binaries: us versus them, self versus other. We see non-humans as being unlike us, and our approach to them is often in line with ideas of separation and difference. To understand the whys of the Anthropocene, we must grapple with new ways of thinking about old things. This includes concepts like Cartesianism, corporeality, complexity, positivism, and epistemology. Broadly, decoloniality encourages us to be aware of the hierarchical thinking that affects wider structures of culture, politics, and the environment.

By opening up our perspectives to modes of deconstructing power, we can share in responding to the ethical challenges threatening Earth. To move forward consciously, reshaping our understandings of power, capital, technology, and colonization are essential. The concept of the Anthropocene might seem bleak; however, forging paths forward with the Earth in mind can help cultivate new understandings and responsibilities of humans.

Discussion Questions

Exercise

Donna Haraway, inspired by Bruno Latour, invites her readers to see ourselves as part of a larger community of “compostists.” Compostists see themselves as symbiotic with all parts of the world and, as such, initiate “world caretaking” and “repairing damaged places.” To inhabit the mindset of a compostist requires trying to understand one’s impact.

For this exercise, pick an object in the room—it can be anything from a lightbulb to a tassel on a rug. Study the object and reflect on the various materials, mechanics, processes, and functions that brought it to where it is now. Having broken down the object into its parts and processes, reflect on it from a compostist view. How would you remedy the processes of its creation/transport/usage? Or should you?

Additional Resources

Crutzen, P.J. and Stoermer, E.F. (2000). The “Anthropocene”. Global Change Newsletter, 40(June):17-18

Didur, J. and Shaw, D.. (2021). “Representing the Anthropocene.” Speculative Life Cluster. https://speculativelife.com/representing-the-anthropocene

Ellis, E.C. (2018). Anthropocene: A very short introduction. Oxford University Press.

Global Canopy Program. (2014). “Planet Under Pressure.” Vimeo. https://vimeo.com/117910068

Global IGBP Change. (2021). “Great Acceleration”. International Geosphere-Biosphere Programme. http://www.igbp.net/globalchange/greatacceleration.4.1b8ae20512db692f2a680001630.html

References

Andersen, G. (2020). Climate fiction and cultural analysis: A new perspective on life in the Anthropocene. Routledge: Taylor and Francis Group. Earthscan.

DeLoughrey, E., and Handley, G. (2011). Postcolonial ecologies: Literatures of the environment. Oxford University Press: New York.

Ellis, E.C. (2013, Sept. 3). Anthropocene. The Encyclopedia of Earth. https://editors.eol.org/eoearth/wiki/Anthropocene

Ellis, E.C. (2018). Anthropocene: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press.

Grusin, R. (2017). Anthropocene Feminism. University of Minnesota Press.

Haraway, D. (2016). Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Duke University Press.

Steffen, W., Crutzen, P.J., and McNeill, J.R. (2007). “The Anthropocene: Are humans now overwhelming the great forces of nature?” Ambio: ABI/INFORM Collection, 36(8):614- 621.

Todd, Z. (2015). Indigenizing the Anthropocene. In H. Davis & E. Turpin (Eds.), Art in the Anthropocene: Encounter among aesthetics, politics, environments and epistemologies (1st ed., pp. 241- 255). Open Humanities Press.

Trump, D. [@realDonaldTrump]. (2012, November 6). The concept of global warming was created by and for the Chinese in order to make U.S. manufacturing non-competitive [Tweet]. Twitter. https://insideclimatenews.org/news/09062017/five-shades-climate-denial-donald-trump-scott-pruitt-rex-tillerson-jobs-uncertainty-white-house/

N. Bucky Stanton is a PhD Candidate in the department of Science & Technology Studies at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. His dissertation investigates natural and cultural resource extraction in the central Peloponnese of Greece, exploring the history and politics of archeology, energy and modernity in contemporary Greece.

On a searing summer afternoon in southern Greece, a history is being constructed by an archaeological machine. I am part of this machine, acting as a topographical surveyor. Using metal rods with reflective mirrors and an electronic measuring device known as a Total Station, we record the site as a series of data points that are later processed into a simple map. From there, a digital rendering is created. This process takes place for every trench, every excavated layer, and every significant artifact (pieces of metal, fragments of statues, large blocks of stone, etc.). After the topography team is done, the survey team takes measurements that they align with spatial and temporal models of the site. As we call in by radio to give my supervisor another data point, I wipe the sweat from my brow and scan the lower sanctuary of Mount Lykaion.

Before me is an array of things, people, and techniques, all working together to excavate, analyze, and produce an understanding of the site. This array includes: the survey data on the hard drive of the Total Station; plastic buckets loaded with newly excavated, muddy tiles; yesterday’s trowels and shovels waiting to be sharpened; site directors and supervisors discussing their findings and how they align with the description of the site made by the ancient geographer, Pausanias; and LIDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) data. My supervisor radios back to confirm reception of my data and to tell me to hop in a trench while he starts up the drone to take aerial photographs.

I jump into the closest trench, ready to help. It is dense with material today, including partially exposed ceramics, animal bones, and other refuse requiring systematic, layer-by-layer, excavation. Helping one of the archaeologists, I pull out a fairly intact roof tile. We discuss its features. Using her scholarly expertise, the archaeologist identifies it as a vaguely Hellenistic tile, Type 1 or 2, noting the texture and color of its exposed center. She then tells me excitedly about an earlier find from another trench, a small piece of rare pottery. Soon, the work day ends, and we pack up. I carry back a weighty bucket of tiles, along with my survey equipment, back to the vans. We return to the laboratory in the village below the site.

Back at the lab, the organic and non-organic artifacts are gently cleaned, left to dry in the sun, and further processed. The lab team ‘reads’ the artifacts and fits them into existent categorization models. Minor differences in the color, texture, and consistency of ceramic materials results in them being given different names, interpretations, and chronological assignments. Using microscopes, chemical analysis, and other methods, the lab team interprets the artifacts further, in order to make their ultimate interpretation. These interpretations are not unique to our archaeological site, but are also referenced to a meta-collection of materials that have been catalogued throughout the archaeological excavation. This means that they also are subject to the same assumptions, ambiguities, and mistakes that have previously been made in classifying other artifacts.

This whole excavation machine produces “artifactual data,” which is both influenced by and influences classifications across the field of archaeology. Yet the history it constructs is multiple, which means it can be organized and understood in different ways. For example, it could be aligned with a period in history (e.g., the “Early Helladic I”), a discipline (e.g, “Eastern Mediterranean Iron Age Archaeology”), or a publication (e.g., the book, Wonders and Mysteries of Mount Lykaion). Together, the excavation machine, the data, the way it is interpreted, and how it aligns with previous work creates an assemblage.

What makes it an assemblage is that, even as it can be put together in one way, it can also be continually undone and re-done by other work. Over time, historical periods are questioned and redefined in the face of new evidence. Disciplines expand and contract as their frameworks are negotiated by practitioners and the institutions that maintain them. And books are researched, written, and published, but then face being dismantled as readers experience and interpret them. (In some cases, books are also dismantled by the humidity of the room they are kept in, by the transformation of the languages in which they are written, and by other changes.) Assemblages are inherently able to live, grow, decay, and even die as the elements and relationships that make them change over time.

The archaeological assemblage I participated in on Mount Lykaion is further embedded in other structures and relationships, themselves assembled: foreign and regional universities that operate excavation sites; scholarly societies and funding institutions; the Greek national ministry of culture and its local branch; policies that govern artifact removal; storage and shipment practices that the Greek state and foreign nations negotiate. Even more broadly, the assemblage is also connected to the cultural heritage funding schemes of the European Union and institutions like UNESCO World Heritage. And, transecting all these bodies and processes are the effects they produce, from the production and value of artifacts to heritage management plans and even feelings of wonder and connection to the construction known as ‘the Western tradition’.

At the level of theory, an assemblage holds its many parts together, forming a productive arrangement that is often enveloped by other assemblages. The example above is about archaeology, but the idea of assemblages can apply to all sorts of social situations. We humans are inextricably parts of assemblages ourselves, including other humans, but also the things we interact with and the relationships that guide that interaction. The past itself is not an assemblage, but the ways we represent it, give meaning to it, govern it, and make history from it are.

So why are assemblages important if they are without boundaries and continually changing? It is because the ways we understand them, our definitions and participation in them, also create limits that in turn can create, construct, destroy, and redefine other assemblages. By understanding that assemblages are a conceptual representation of the constant ‘tuning process’ of both social and material forces, we can critically understand that neither the social nor material is pre-given. By extension, the fundamentally defined elements of experience—and the additive thing we call reality—are also not given, inherent, or obvious. Everything is made. Concepts are physical and matter is abstract.

Discussion Questions

Additional Resources

Agamben, Giorgio. 2009. “What Is an Apparatus?” and other essays. Meridian, Crossing Aesthetics. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Buchanan, Ian. 2021. Assemblage Theory and Method: An Introduction and Guide. New York: Bloomsbury Academic.

Deleuze, Gilles. 1992. “What Is a Dispositif?” In Michel Foucault, Philosopher: Essays, ed. Timothy J. Armstrong. New York: Harvester Wheatsheaf. 159–68.

Ada S. Jaarsma is a Professor of Philosophy at Mount Royal University in Calgary, where she teaches existential philosophy, philosophy of science, and philosophy of sex and love. Her recent books are Dissonant Methods: Undoing Discipline in the Humanities Classroom, co-edited with Kit Dobson, and Kierkegaard after the Genome: Science, Existence, and Belief in This World. She holds a SSHRC Insight grant, “Placebos Talk Back,” and is working on a collaborative, transdisciplinary project on placebos.

Suze G. Berkhout is a clinician-investigator and psychiatrist at the University of Toronto and University Health Network. Her program of research in feminist philosophy of science/STS uses ethnographic and narrative qualitative methods to explore social and cultural issues that have an impact on access and navigation through health care systems. She focuses on the epistemic and ontological importance of lived experience in relation to knowledge in/of medicine, and related to mental health, including treatment resistance in mental health, early psychosis, transplant medicine, and placebo/nocebo studies.

Decartes video animation: Eva-Marie Stern & Maya Morton Ninomiya

Cartesianism is the shorthand term used to categorize ideas that reflect the 17th-century philosophy of René Descartes. Precisely because Descartes’s approach to knowledge continues to shape ideas today, his last name has become a placeholder for particular knowledge claims. Whenever there are specific dualisms at play in an argument or method, they can be described as “Cartesian.” A dualism is a binary or a split; it works to keep separate two entities or dynamics, like subjectivity and objectivity. The most famous dualism that lines up with Cartesianism is the mind/body dualism.

Descartes upheld a ‘theory of mind’, in which the body is entirely separate from the mind. In many cases, it is tempting for researchers—and for members of the public—to assume that this Cartesian theory from long ago is still valid today. Contemporary theorists like M. Remi Yergeau, who is a Disability Studies scholar, lay out a competing theory of mind in which bodies and minds are entirely entangled with each other.

The adjective, “Cartesian,” can be used as a neutral descriptor to point out ideas that align with Descartes’s, but more often, it is used as a criticism or a corrective. One reason for the negative association between Descartes’s ideas and contemporary research has to do with the impact of dualisms themselves. Dualisms like the mind/body split can be so prevalent that they can be hard to recognize, and even harder to overturn and replace with methods that affirm dynamic connections between bodies and minds.

When researchers study things without interrogating their own Cartesian commitments, it can lead to faulty or even prejudicial research methods. Consider the case of the placebo effect, in which a placebo (like a sugar pill, a doctor’s white coat, or a sham surgery) might prompt palpable healing in a patient. The Cartesian mind/body dualism can block a researcher’s capacity to study these dynamics: they might refer, for example, to the ‘mere’ placebo, a phrase that locates placebos “only in the mind” of patients rather than in real-world interactions between patients, treatments, bodies, and minds.

Such phrases can pose risks to research methods because, as Bruno Latour explains, they set minds (or representation) in competition with bodies (or even reality itself). Latour offers an instructive way to make sense of this competition: he calls it a “zero-sum understanding” of minds and bodies (2004, p. 8). Whenever Cartesian dualisms are at play, there can only ever be competition between minds and reality. Thanks to decades of research in cognitive science, disability studies, science studies, and other disciplines, we now understand that our minds are not separate from our bodies, nor are they in competition with reality. Research methods are developing that take cues from this understanding. Margaret Price, for example, suggests that we use the word “bodymind” to overthrow the dualism all together (2014).

This suggestion is an ethical and methodological one. There can be both harmful and healing effects that arise from interactions between physicians and patients. When a patient is advised that they might experience a negative side effect from a treatment, for example, even if that treatment happens to be a placebo, they may well develop the adverse (unpleasant or negative) symptom: this is called a nocebo effect. Similarly, when someone has experienced trauma in medical (or medicalized) settings, they might experience nocebo effects in medical situations in the future.

The ethical stakes of nocebos extend to the methods by which patients are told about potential side effects, as well as to the affects and relational dynamics between doctors and patients, and to the designs of spaces like doctors’ offices and medical institutions. More broadly, the ethical stakes of Cartesian dualisms extend to the very assumption of who gets to count as human in the first place. If “human personhood” is tied closely to particular kinds of consciousness or cognitive capacity, then lines can get drawn around who is and who is not “conscious,” ultimately informing who is (and is not) deserving of ethical consideration as human.

Exercise

Watch the three videos in the following order:

One or more interactive elements has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view them online here: https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/showingtheory/?p=104

One or more interactive elements has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view them online here: https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/showingtheory/?p=104

One or more interactive elements has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view them online here: https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/showingtheory/?p=104

To read the video transcripts, see below.

In the first video, we travel back to 1641, the year in which Descartes wrote his Meditations, where we discover two thought experiments Descartes would like us to undertake, from our own first-person perspectives. As a first thought experiment, notice how you might be deceived by your own senses. (Note that this experiment goes against the grain, almost completely, of empirical research methods, in which the senses are key for achieving reliable knowledge.) Can you think of an example in which one of your senses led you astray? As a second thought experiment, reflect on whether you have ever been deceived by a charismatic or ‘evil’ genius. Updating Descartes to our own era, can you think of someone, perhaps a famous influencer or expert, who convinced you of something that you later realized was false? Thinking through these two hypotheses from Descartes’s first three Meditations is a way to experience how or why Descartes’s ideas have proven compelling for centuries. Descartes’s enthusiasms about doubting are connected to humanist presumptions about freedom: if you can ‘think,’ then you can doubt and demonstrate your own essential freedom as a human.

In the second video, we move all the way into the present day, in which biomedical research into the placebo effect has led to additional research into the nocebo effect. Such research helps us to question and overturn Cartesian dualisms. This video was initially created for psychiatry residents at the University of Toronto, who needed to learn more about the ethical stakes of their own clinical work. What do you think is the key lesson for the psychiatry residents in this video? How would you explain the ethical significance of nocebos, in your own words?

In the third video, we hear from the artists who designed and drew the animation for the video, “Lessons from the Nocebo Effect,” Eva-Marie Stern and Maya Morton Ninomiya. They explain the various choices that they made, as they worked together to try to visualize the nocebo effect in ways that illuminate rather than obscure bodymind connections. Did this conversation with the artists change your own initial impressions of the nocebo animation in any way? Which choice did you find the most effective, in terms of visualizing the bodymind connections? How is the theory of mind, visualized by these artists, different from the 17th-century theory of mind that you encountered in the Descartes video?

Discussion Questions

Additional Resources

Descartes, Rene. (2008). Meditations on First Philosophy. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Jaarsma, Ada S. and Suze G. Berkhout. (2019). Nocebos and the Psychic Life of Biopower. Symposium, 23(2): 67-93.

Berkhout, Suze G. and Ada S. Jaarsma. (2018). Trafficking in Cure and Harm: Placebos, Nocebos and the Curative Imaginary. Disability Studies Quarterly. 38(4).

Bernstein, Michael H., Cosima Locher, Tobias Kube, Sarah Buergler, Sif Stewart-Ferrer, and Charlotte Blease. (2020). Putting the ‘Art’ into the ‘Art of Medicine’: The Under-Explored Role of Artifacts in Placebo Studies. Frontiers in Psychology. 11. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01354

Latour, Bruno. (2004). How to Talk about the Body? The Normative Dimension of Science Studies. Body & Society. 10(2-3): 205-229.

Price, Margaret. (2014) The Bodymind Problem and the Possibilities of Pain. Hypatia 30(1): 268-284.

Shelvin, Henry, and Phoebe Friesen. (2020). Pain, Placebo, and Cognitive Penetration. Mind & Language. DOI: 10.1111/mila.12292

Ventriglio, A., and D. Bhugra. (2015). Descartes’ Dogma and Damage to Western Psychiatry, Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences. 24(5): 368-370.

Yergeau, Melanie. (2013). Clinically Significant Disturbance: On Theorists who Theorize Theory of Mind,” Disability Studies Quarterly. 33(4).

Video Transcripts

Descartes’s Meditations (1641)

Descartes’ “Meditations” was written a long time ago, but in a lot of ways, it was written to you as a modern thinker. Descartes writes, “I marvel at how prone my mind is to errors.” And what he’d really like to do is invite you to marvel at the very same thing: to marvel at the errors in your own mind.

As a student, you’re likely already pretty good at this. Isn’t it true, for example, that a lot of the opinions that you held on to when you were young are no longer all that convincing or even plausible? But here’s the problem that Meditation One wants us to grapple with. It’s the problem of being deceived by our own senses. “Surely,” Descartes writes, “whatever I had admitted until now as most true, I received either from the senses or through the senses.” How can we find a way to question those truths that seems so certain, precisely because they stem from our own perceptions and sensations? [00:01:00] Descartes gives us a pretty creative method, which is to hypothesize that we’re dreaming. We’re not even awake. Of course, potentially our taste buds are lying to us, if we think that a strawberry tastes delicious, if it’s happening in a dream. This is a great way to prompt some doubt that wouldn’t otherwise take place.

But notice that Descartes is relying on an idea of thinking that is not how we think about thinking. He’s writing in 1641, almost 400 years ago. And he is envisioning our minds as containers. They are containers for one important thing: ideas. Everything we think is an idea, an idea in our mind. I might taste that strawberry, but, on Descartes’ philosophy, what’s really happening is that everything in the mind is having an idea. Including even the idea that came from a sensation.