One or more interactive elements has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view them online here: https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/onhumanlearn/?p=236

Figure 1: Unlearning and Unsettling Trailer

Alternative versions:

Click here for a version with ASL

Click here for a version with LSQ (coming soon!)

Story

Objective: To examine and unlearn individual, institutional, and societal maladaptive assumptions and conventions that block designing learning for human diversity, variability, and equity and global complexity.

Our education system has been designed to treat everyone the same: equality over equity, often under the guise of fairness. It serves, often overtly, as a gatekeeping system that ensures that the students who graduate out of the system have the same core set of skills, knowledge, aptitudes and practices. We have a system that is often designed to ensure sameness within a student body that is unique and for a world that is complex and messy.

Using a liberating structure, post-secondary educators reflected on what it means to unlearn and unsettle our current education model.

Origins in Years of Unlearning (Jutta’s story)

The following is a telling from two decades of experiments with unlearning in the university classroom. The area of study is inclusive design, but the assumptions that are tackled go beyond the area of study. This experience, and the community that supported it, motivated this project for me.

The field and practice focused on inclusion and equity (that I grew with my team and community), holds two things to be true: we need diversity to survive and thrive and the world and our lives are increasingly complex, entangled, and changing. What follows from these truths is that learning must be lifelong and adaptive, learner difference is a strength and should be nourished, and an important skill is collaboration across difference. The formalized education system we were part of seemed to explicitly and implicitly deny and/or reduce these truths. Signs of this denial could be found in the conventional vocabulary of the academy, which included “terminal” degree completion, disciplinary domains and rigour, standards compliance, and student ranking. Proof of independent production was mandatory, and collaboration was suspected as cheating. This was asserted despite the assignment of redundantly performed exercises that had no value beyond the classroom, within a cohort and across years of cohorts. Disciplines were explicitly and implicitly defended through insider language, insider rituals, and tacit hierarchies, thereby discouraging collaboration across disciplines or incursions by peerless upstarts. The practice in the academy seemed to be to make it harder for students to be admitted, participate, and learn, so only those who could conform would survive. The challenge for students seemed to be to compete to climb an ever-steeper hierarchy. The research pinnacle to be attained depended on statistical significance, isolated conditions, and replication across contexts, assuming homogeneity that could only be achieved by the majority. The people within our community, who tended to be outliers and small minorities, were consistently marginalized or excluded. Yet, we knew they sparked the greatest innovation and offered the greatest essential diversity.

Moving my team to a university that was more welcoming of alternative education design, I started a graduate program in inclusive design. The program engages students in inclusively co-designing their education while learning about the emergent field of inclusive design. I knew that before students could engage and learn in the program, they needed to unlearn and question many of the socialized assumptions and conventions inherent in formal education. The introduction to the program is a two-week in-person intensive called Unlearning and Questioning, until the pandemic when it moved online over the period of a term. Consistent with inclusive design, a cohort is chosen that includes the greatest diversity of perspectives, including many students with lived experience of barriers. The ultimate goal of the course is to create a cohesive learning community across difference: “finding a deeper commonality by making room for difference.” The formal academic objectives are:

- To learn to give and receive constructive critique (marks come from self-assessment, peer assessment, and consultation with the instructor; grades are arrived by evaluating personal learning not cohort ranking),

- To question entrenched assumptions that are antithetical to diversity and equity and that ignore complexity, and

- To create a personal and community learning plan as a living plan to evolve as the context changes and new insights emerge.

While the class is prepared that “we will all offend, we will all be offended, it is how we respond that is important,” the class begins with activities that establish kindness, generosity, and trust as the practice, before delving deeper into difficult topics that might be divisive. Many of the class activities are social to encourage social cohesion. The class reflects on shame, blame, polarization, winner/loser mentality, the inequity of influence, and the diverse forms of power. The class creates strategies for moving from personal achievement to include collective achievement. We practice hearing from unheard voices, entering difficult conversations, and listening. We question our reactions and judgments. We discuss the misguided stigma associated with failure and mistakes. We work to value struggle and changing or expanding our views. I try to model caring self-critique and making room for a spectrum of stances, rather than two sides.

The actual course content or syllabus is tailored to the students that participate and the topics that are top of mind at the time. Guests are invited that challenge and stretch perceptions and presumptions. These have included guests with lived experience of homelessness, prostitution, slavery, extreme poverty, war, and terrorism. Guests and students share experiences through dance, humour, cooking, play, and conversation.

Over the years, consistent themes have emerged covering assumptions that require unlearning. We address these through current examples, or examples from the student’s lived experience. These are:

- The false notion of an average human and how this undergirds favoured research practices, AI, markets, etc.; the importance of attending to the margins and outliers and the entire spectrum of perspectives

- The misguided notion of survival of the fittest — both to unlearn what is thought of as fitness and the mistaken understanding of advances in evolution through the elimination of the weak, rather than the flourishing of diversity

- The idea of efficiency and productivity and to increase the understanding of the ultimate costs of things like the 80/20 principle, to discuss the need for a circular economy both in terms of environmental and social sustainability (disparity, social cohesion, etc.)

- The costs and damage done by categorizing/classifying/labelling

- The devaluing of fragility and vulnerability; the value of mistakes and failure

- The problem with best, perfect, and utopia (hierarchies, class); the value of change

- The problem with completeness, arrival, certification in an entangled changing world (complex adaptive systems)

In every case we ask: Who benefits (through gains such as popularity, wealth, or power), who is left out, what is the ultimate impact on our world or the common good?

We continue with the topics that are top of mind for the students, and I share what I’m struggling with as a class participant. The task for the remaining time is to weave these alternative perspectives together into an evolving mindset that can be continuously tested, enhanced, and matured.

I purposely and carefully hand over the leadership of the class to the students, intervening with a light hand when needed, and assume the role of fellow learner. I have witnessed again and again that a powerful key to student engagement is to put students in the role of teacher/learner. I firmly believe that I have learned the most from these classes.

Why This Topic? Unlearning and Unsettling

Questioning and Reflecting

Figure 2: Photo by Lukasz Szmigiel on Unsplash

Among the domains to be examined are research, evidence, metrics, innovation, ways of knowing and expressing knowledge, value systems, work, intelligence, economics, decision-making, notions of quality, rigour, integrity, efficiency, winning, and trust as they relate to learning. To move forward we have to interrogate how we practice now and why. Some of this is the uncomfortable work of unlearning and unsettling. We do this work by embracing questioning and reflecting as we explore the way education is designed (from the physical environment, the virtual environment, the interactional environment, and more). Among the lessons we learn in unlearning and unsettling are the following:

- Unbottle-able: we cannot package this work up and make it “scale.” Scale is a word that harkens to the economics of the enterprise, not to the learning outcomes or cultural impacts. We cannot copy and paste modules into different contexts and expect the same results. In fact, we should pause and consider the impact of expecting results at all. Many times, the process is more important than the outcome or any single outcome.

- Time to think, time to reflect, slow learning, importance of pauses: when do you take time to explore, wonder, critique, interrogate, question yourself and your own practices as well as those of others and of institutions? Time and attention are perhaps our most valuable commodity, and it is in short supply. What is lost when we schedule meetings back-to-back and never have a moment to think, digest, let our minds wander to make connections? This is the sawdust of our work. As we cut clean, exact lines we create “waste” in the dust. But what if the dust is the good stuff? What if we accidentally leave something behind in the dust? What if the voices and the people we hope to reach the most with this work fall into the dust? We have to be aware and wary of every cut we make.

- Structured structurelessness: in doing this work we acknowledge the need for structure while simultaneously warning that too much structure can curtail curiosity and exploration. So, we advocate for only as much structure as is absolutely necessary for people to have clarity of purpose, but no more. And in that space that is created, we can all consider how things might be. We put education in a straitjacket and then we’re surprised when it isn’t whimsical, innovative, creative, and free. How do we interrogate the usefulness and uselessness of the structure in rubrics, checklists, gatekeeping, rigour, prerequisites?

Co-design Session Topic Introduction:

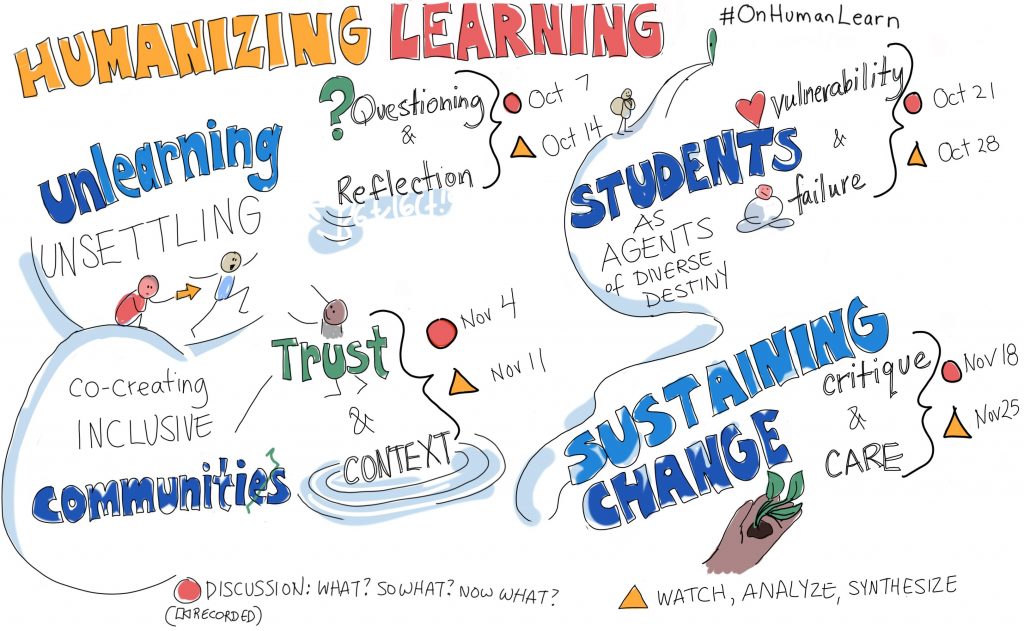

Humanizing Learning: Unlearning and Unsettling

How to Create Brave Spaces

This co-design topic had the burden of being the first that we undertook. We wanted participants to feel brave and welcome and to have a sense of how inclusive, brave spaces work: how co-design happens. So, we created an introductory video to help participants calibrate their expectations and show up ready to share! The video can be accessed here: Creating Brave Spaces video; Creating Brave Spaces ASL.

One or more interactive elements has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view them online here: https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/onhumanlearn/?p=236

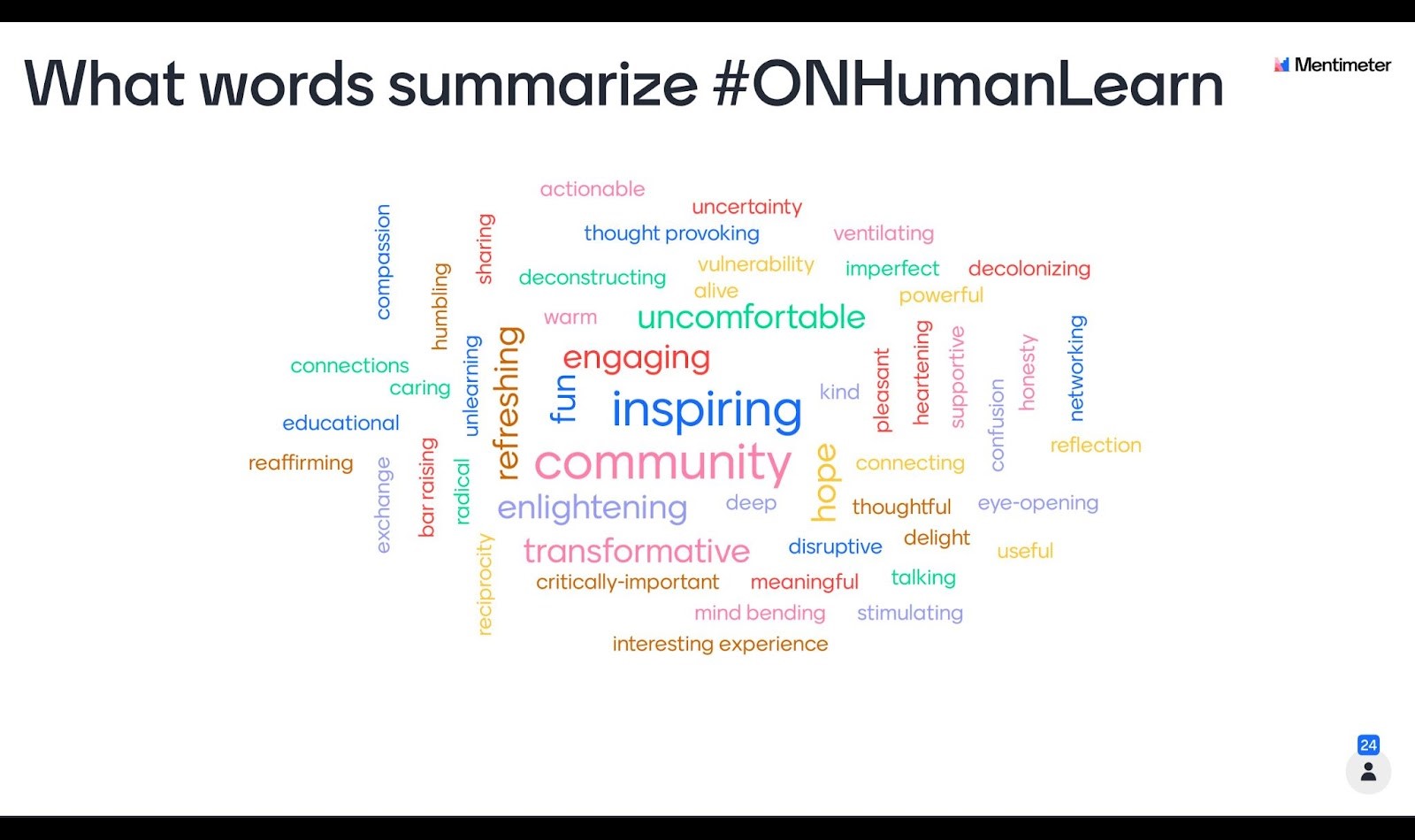

Figure 3: “#OnHumanLearn — Creating a Brave Space”

Click here for a version with ASL

Click here for a version with LSQ (coming soon!)

How to Set the Stage

Once participants joined the co-design session, Dave Cormier and Jess Mitchell used inclusive facilitation practices to explain the topic and intentions and then to let go. A 9:40 capture of the introduction to the topic and the co-design sessions can be seen here:

Dave Cormier and Jess Mitchell Discuss How to Humanize What We Do …

One or more interactive elements has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view them online here: https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/onhumanlearn/?p=236

Figure 4: Dave Cormier and Jess Mitchell discuss how to humanize what we do.

Click here for a version with ASL

Click here for a version with LSQ (coming soon!)

Introductory Reading and Framing

To successfully humanize learning in postsecondary education requires a fundamental, system-wide change in mindsets and practices. Checklists of criteria, institutional statements and guidelines, and token add-ons to educational offerings will not suffice. This change in mindsets and practices is urgent. The pandemic has shown that we must address escalating inequities, prevent divisiveness, and build a more inclusive society in Ontario so we can weather the crisis to come.

And we know many of our practices within the larger, complex system of Education are not designed to be humane. We need to unlearn many of those systems, both as learners and teachers, in order to make our learning spaces brave and healthy for everyone. This topic is the beginning of an eight-week #OnHumanLearn conversation on humanizing online learning funded by the eCampus Ontario Virtual Learning Strategy grants.

We have, most of us, been deeply unsettled in our personal, social, and professional lives over the past few years. Many of us continue to grapple with being settlers on stolen land (where, in some cases, there has only recently been a “racial awakening”): land where some in our broader communities have never been safe or supported or treated fairly. Our project is, hopefully, about addressing this moment in time by reflecting on where we are and how we can do better … through learning and unlearning.

Figure 5: Photo by Tomas Eidsvold on Unsplash

It is with this call to action, then, that we want to talk about how we can bring more humanity to the part of the world that we can impact or influence, to classrooms, homes, and all the places where teaching and learning happen. Each of us will have different things to unlearn, different places where we unsettle and are unsettled. We want to come together and hear from all of you; to learn from you and have us all unlearn together. The links within this document are included to provide attribution to the exemplary work that precedes and informs this project. We do not expect you to review all these resources in order to participate in the conversation.

Some questions that have informed the project facilitators to date:

- What do we need to “unlearn” in order to move forward with equitable, humanized teaching and learning?

- What of our past has led us to thinking and doing in ways that limit us?

- When have our different privileges and our “settled states” interfered with being human in the context of teaching and learning spaces?

- What existing systems within education encourage or influence our decisions away from the humane?

- How do we rebuild spaces to stretch and embrace TRC, #BlackLivesMatter, and others who have been and are marginalized and oppressed in our learning communities?

- How do we ask the right questions about our need to unlearn and unsettle?

Learning and Unlearning in the Pandemic

Throughout the pandemic, a popular narrative of online learning as “less human” has gotten a lot of media airplay, from both a faculty and a student perspective. From faculty we’ve heard stories of staring at empty video windows and students using online websites to cheat on their exams. From students’ stories of being forced to watch three hour audio lectures and falsely being accused of cheating by test surveillance software, we have cause to wonder what we should be doing with our classrooms in an online world. But is the pandemic really to blame? Is online learning to blame?

Building on the work of educators such as Whitney Kilgore in the US, Maha Bali in Egypt, and the works of many others, we hope to have a conversation about what we can do to make learning experiences more humane. In “Learning to Unlearn, and then Relearn: Thinking about Teacher Education within the COVID-19 Pandemic Crisis” Fernandes and Gottolin invite us to look “at the metaphoric invitation this COVID-19 pandemic has sent us to revisit our praxis.” They suggest educators should take this opportunity to take stock of what we need to unlearn to make our classrooms and educational systems different.

The first dimension of #OnHumanLearn teammate Jutta Treviranus’s framework for inclusive design is to recognize human uniqueness. Our education system, however, has been designed to treat everyone the same: equality over equity, often under the guise of fairness. It serves, often overtly, as a gatekeeping system that ensures that the students who graduate out of the system have the same core set of skills, knowledge, aptitudes, and practices. Interestingly, we have doubled-down on this even in light of it not preparing people for an uncertain and complex future.

We have a system that is often designed to ensure sameness with a student body that is unique and for a world that is complex and messy.

In her post on Hybrid Pedagogy, Jessica Zellner wonders, given the current state of the world, how we can consider ourselves students-centred when

Our syllabi are a bloated ten pages long and thick with policy statements, as too many in education have come to believe that good teaching and rigid rule enforcement are one and the same: no late work accepted; grade deductions for late arrivals; required use of surveillance software; “fairness” as represented by uniform punishments regardless of personal circumstance or hardship.

“Where,” Jessica asks, “is our humanity?”

Erica McWilliams, in her Unlearning Pedagogy, tells us that habits “are useful when the conditions in which they work are predictable and stable.” She wonders, in 2005, if the world that our students are going out to is predictable or stable. She talks about the seven deadly habits that we have taken on as teachers; “deadly habits” that need to be unlearned:

- The more learning the better.

- Teachers should know more than students.

- Teachers lead, students follow.

- Teachers assess, students are assessed.

- Curriculum must be set in advance.

- The more we know our students, the better.

- Our disciplines can save the world.

Jennifer Hardwick of KPU tells how she has had to learn to “let go of my ego and embrace discomfort by learning and unlearning, decentring myself, and re-thinking and re-designing when something isn’t working. It means committing to inclusion and justice in my classes and preparing myself so that I can ethically and knowledgeably talk to my students about difficult topics as they arise: climate grief, genocide, racism.”

Different voices from across the field. We’d like to hear your voice and add to the discussion.

- What are we unlearning? What do we need to unlearn? What is unlearning?

- Why do we need to unlearn? Why is unlearning important? For whom? For what outcome?

Findings from the Co-Design Participants

Week 1: “What?” and “So What?”

- How do I reflect on and identify what I need to be changing?

- Owning your truth can be uncomfortable and unsettling but it is courageous and vulnerable

- Notice the outcomes you’re asking for; consider process outcomes

- We tend to privilege production over process

- Students are not a product! Get rid of productivity-focus

- We can change our classrooms, but we will still be faced with constraints

- There are tensions between hierarchies that serve us and that don’t

- Challenge the norms set by administrative bodies, such that the learning is relevant to students

- We try to protect ourselves from being uncomfortable, but discomfort and vulnerability are essential to consider what another person might be experiencing

- Unlearning is harder to do than learning

- Virtual learning eliminates informal conversations before class — “How are you?”

Week 2: “Now What?”

- Students feel free to interact with staff when there are no grades being assigned to a lesson

- Students worry there is trickery (when process is privileged over product)

- Assessment and grades don’t help with intrinsic motivation — “What do I need to do to get an A?”

- Conduct open book exams — we live in a world where people can look things up online

|

What?

|

So What?

|

|

Focus on process > product

|

Small classes 10–20 (optimal and raise the issue of scale as an economic, not pedagogical rationale)

Build rapport by sharing experiences

Pass/fail classes

Self-assessments

|

Link to Session Materials

Humanizing Deck

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/onhumanlearn/?p=236#h5p-1

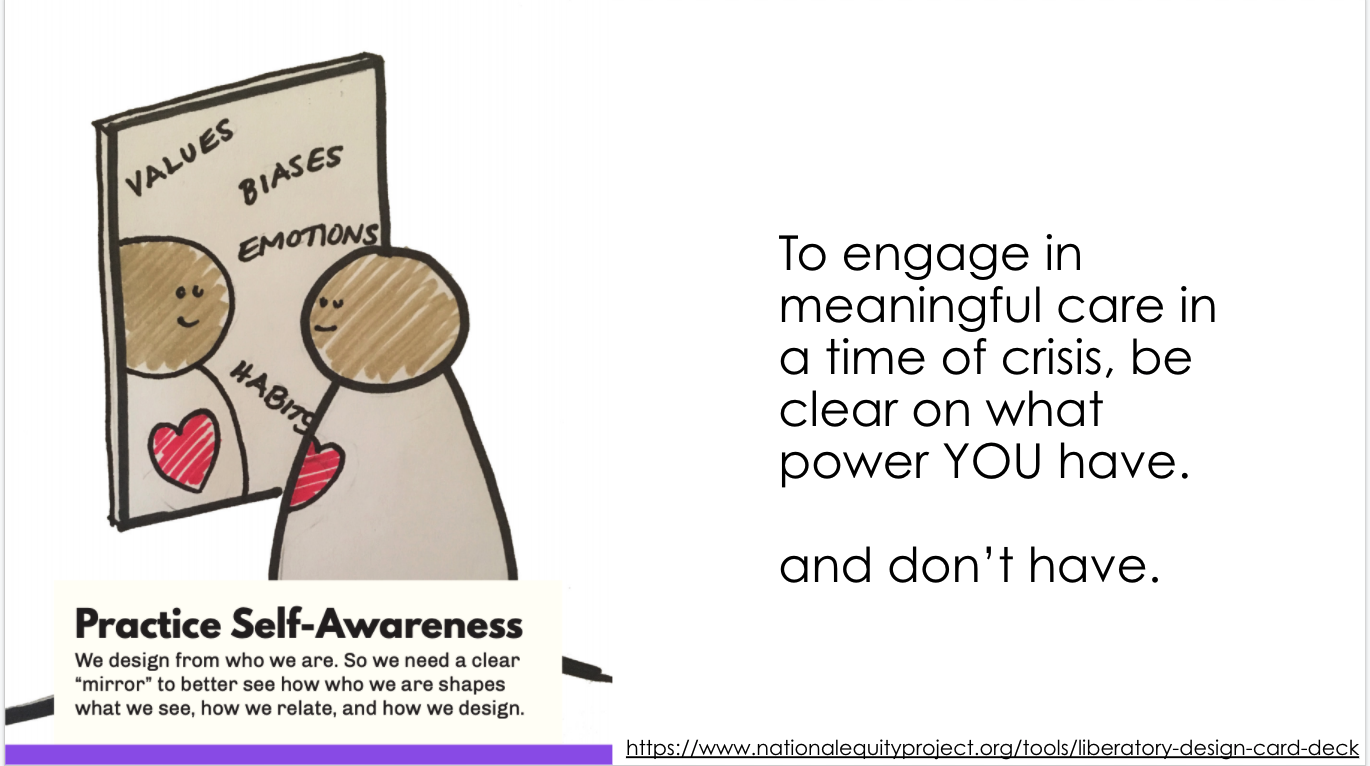

Figure 5: Humanizing Deck slides

Slide 4: Unlearning 4

We were building trust without any expected outcome. We weren’t “on task” — we were building something together. We’ve been adjacent, but we haven’t been together.

Slide 5: Unlearning and Unsettling in Teaching and Learning

We’re here to talk about unlearning; we’re not looking for a definition, we’re hoping to do things differently today, and that might feel awkward …

Don’t solve or try to solve things today. Explore what you’re thinking openly, and be open to what others are saying. Think about edge cases.

We want you to wonder, explore, and share ideas about unlearning that might come from your own experience or influences. We all come from different spaces, have different histories, different experiences … and we bring those with us into every interaction. I think of it as the backpack we all carry on our backs.

Slide 6: What? So What? Now What?

Jess’s Unlearning: Efficiency — which ones are good and which ones do harm?

Economics of Education: I’m not naive enough to be totally tuned out to the economics, but I’m disappointed that it isn’t transparent and we don’t talk about the decisions that are made in the design of education that have everything to do with economics and nothing to do with teaching or learning.

Slide 7: Moving to Break-Out Groups

Notice who is volunteering to take notes. Notice who, historically, usually takes notes (young, junior women). Think for a moment about how the rest of the group (you) can support whomever is taking notes so that they can actively participate and not just be the scribe with no brain or opinions. After a shared experience, ask, “What? What happened? What did you notice, what facts or observations stood out?” Then, after all the salient observations have been collected, ask, “So what? Why is that important? What patterns or conclusions are emerging? What hypotheses can you make?” Then, after the sense-making is over, ask, “Now what? What actions make sense?”

This is all in an effort to humanize learning.

- What: What are we unlearning? What do we need to unlearn? What is unlearning? The unsettling can be at least two things: you can feel queasy from the unlearning, and that can be unsettling; you can also fundamentally interrogate the provenance of the structures you’re unsettling and that can have a cascading impact on yourself and others — think about that, together …

- So what: Why do we need to unlearn that? Why is unlearning important? For whom? For what outcome? How can we do unsettling productively? Is that an oxymoron?

Slide 9: Reflecting

What it means to be inclusive — some weren’t here last week. How can we be welcoming, aware of that feeling when you’re new and feel you’ve missed something, or worse, been left out. What is holding us back? Why aren’t we breaking through the structures that are holding us back? In many cases we have real, good, solid reasons. In others, we might still have some room to disrupt (ourselves, others, and the systems around us). Remember: where possible, be brave, not unsafe. What’s preventing you from doing this now? Now what? What do you need? Where can you get it?

Slide 10: Rigour

ASSUMPTION: No one (including you) can tell if you’ve learned anything without a grade.

Aren’t we just falling into relativism — we need not fall into that pit of despair!

Slide 11: We All Want to Be Seen or Heard

Anytime we use a term like “administrators,” “professors/instructors,” “students,” we should ask, “Always? Sometimes? Never?”

So often we do this in conversation … students …

And we do another thing: we bifurcate the world into heroes and straw people (or even bad apples).

Hit man, straw man — cis, white, heterosexual man … (but what if you’re a very shy, first generation university student who grew up in generational poverty?) and yes, you’re cis, white, and straight?

Or the reminder we got last week: not everyone on the land that isn’t Indigenous is a settler — some were plucked from the land or placed on the land against their will, enslaved on the land …

Slide 12: Finding Your Own Voice

How do we balance SELF within INCLUSION? Who gets to have a voice and when? And whose voice gets protected or heard or defended? Do you whisper or do you shout? When some of us shout we command attention; others are written off as angry and not worth listening to. So, folks, don’t you underestimate just how hard it is to find your own voice.

Slide 13: Scope vs. Scale

If we want Education to be humanized, we have to deal with individuals whenever possible. Then we have to do the work to think about how to scope our work — not scale!

Slide 15: This Is What

This can be and will be a dynamic “what.” You’ll be influenced and inspired by good and bad examples; you might find someone to support you in your own personal journey through this. You might have an administrator initiate a change; you might have a department lead upend power with a student group. “Clear eyes, full hearts can’t lose” — Coach Taylor from Friday Night Lights.

Liberating Structure Used and Why

(This little origin story is by Terry Greene)

This team met a number of times in the lead up the eight-week co-design extravaganza. In those meetings the term “structured-structurelessness” was bandied about a few times. It sounded great to me. Sounded like my kind of place to hang out and talk. But what does it mean? I thought about it, likely in an ill-structured way. I thought maybe it meant loosely structured, sure. Maybe also loosely goaled too? If that makes sense. I also kept thinking, like way back there in my brain where the thoughts are mumbled quietly, “Hey, this sounds like those Liberating Structures that I love so much.” They are just basic facilitation steps that, when put in place, give things a structure that is open enough to really let things fly.

After the back of my head mumbled that thought a few times, I actually heard it. I suggested it to the team. “Hey, we should use a Liberating Structure like ‘What, So What, Now What’ as a basis for our sessions!” And, what with all these humans working to humanize things, they heard me out. What if we spent the first week of a module as a group identifying and dissecting the “what” of it? What is “unlearning and unsettling”? What is “vulnerability and failure”? And what if that’s all we meant to cover in that first week? We would be so limited in our focus. But we’d also be so free to go deep with it. And to follow that up with a second weekly meeting to say So What and Now What? Why is this important to us? What action steps can we take?

This Liberating Structure felt just right. It gave us not much to do (we only had to answer three questions over two weeks!) while at the same time it gave us a lot to work with (we had time to go deep and come up with the best plan of action together!). And it allowed a dozen or so separate co-designers to each bring their own diverse approaches in a consistent way. If that’s not structured-struturelessness, I don’t know what is! (Seriously, if it’s not, I don’t know what it is.)

Reflections

Below is a reflection written by Heather Carroll from Nipissing University after Session 1 of Unlearning and Unsettling Co-Design:

Just as learning is a communal process, today I experienced first-hand that unlearning is also best done in community. In the first breakout session of #OnHumanLearn, I was introduced to a group of colleagues who were all, serendipitously, in transition. From PhD to professor, from student to staff, from practitioner to lecturer: we had all recently had a professional shift and confronted deeply ingrained norms about what and who we should be in our new role. Where did these ideas come from? And who do they benefit? Not us. At least, for the most part.

We immediately shared with one another exactly what we needed to unlearn. We shared elements of our identities that we wanted to showcase professionally. Stepping into roles as women, for example, we asked ourselves to unlearn assumptions and untruths about our suitability for roles. Sometimes, we shared feelings of imposter syndrome. Sometimes, we feel as if we are playing the role of a professional. We were all drawn to this larger humanizing group because we felt that it was missing in our current contexts. We all want to humanize education.

We shared examples of toxic behaviours, practices, and policies, both in academia and our professional/disciplinary spheres, and how we could be agents in disruption. “Empathy” and “compassion” were seen as salves we could apply to our lives, and our students, in order to help address toxic elements of higher education. But are those traits enough? And are they inherently good? Flexibility in the age of COVID is necessary … but is it only setting students up for failure in their inflexible future professional lives? We grappled with how we can enact our unlearning within our own loci of control, recognizing that we are located in nebulous systems where change can feel impossible. Can institutions unlearn efficiency and scarcity mindsets? Why does the institution constrain unlearning when it needs to happen at all levels?

Afterwards, I remembered a distinction explained to me in a book talk with Dr. Savannah Shange, whether schools (even progressive ones!) are an “institution” or an “organization.” Put simply, institutions exist to exist. They are self-serving, where organizations exist to get work done and to achieve a desired end. So while we are institutionally constrained in our roles, during today’s session, and the following seven weeks, we are an organization. Our unlearning depends on it. Our humanity depends on it.

Upon further reflection, I am reminded of Dr. Barbara J. Love’s framework for developing a liberatory consciousness, which requires awareness, analysis, action, and accountability. I think, today, we achieved awareness and analysis. I am hopeful, with this critical mass of humanizing educators, we can move towards collective action and accountability.

Reflecting inward, I think about the bravery and vulnerability required to unlearn. In July, Jess asked me to reflect on the process of the experience so far. I used the word “unlearn” once, and it was when I said, “I’m new [here] and I was often criticized for speaking at meetings in a former role, so I am trying to unlearn that. I am grateful for this community <3”

My active unlearning is an ongoing process, and probably why I feel at ease sharing this reflection in writing and not in a large group. My sentiment stays the same: I am grateful for this community.

Linked here is a reflection written by Laura Killam from Queens University after Session 1 of Unlearning and Unsettling Co-Design:

http://insights.nursekillam.com/reflect/now-what-unlearning/

Questions for Future Conversations

- Can we productively unlearn and unsettle while still having clear progress, milestones, and structured learning?

- How can we build in unlearning and unsettling to all aspects of education?

- What can you unlearn today?

Additional Materials

Link to Twitter Conversations

The team created a hashtag that was used to continue conversations on Twitter: #OnHumanLearn

https://twitter.com/search?q=%23OnHumanLearn&src=typed_query

Works Cited

Resources that are especially relevant to the topic.

Fernandes, Alessandra Coutinho, and Sandra Regina Buttros Gattolin. “Learning to Unlearn, and Then Relearn: Thinking about Teacher Education within the COVID-19 Pandemic Crisis.” Revista Brasileira De Linguística Aplicada, SciELO, 19 May 2021, https://www.scielo.br/j/rbla/a/PZnXf4cFWTH8LrgpFP5WVdy/.

Gordon, Mordechai. “Welcoming Confusion, Embracing Uncertainty: Educating Teacher Candidates in an Age of Certitude.” Paideusis, vol. 15, no. 2, 2006, p. 15–25. https://doi.org/10.7202/1072677ar.

Hardwick, Jennifer. “Now Is the Time to Be Brave: Pedagogy for a World in Transition.” Teaching Learning Commons, KPU, 25 Aug. 2021, https://wordpress.kpu.ca/tlcommons/now-is-the-time-to-be-brave-pedagogy-for-a-world-in-transition/.

Humanizing Learning. https://www.zotero.org/groups/3361442/humanizing_learning.

McWilliam, Erica. “Unlearning Pedagogy.” Journal of Learning Design, 2005, https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1066452.pdf.

Wheatley, Margaret. “Partnering with Confusion and Uncertainty.” Margaret J. Wheatley, Shambhala Sun, Nov. 2001, https://margaretwheatley.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/Partnering-with-Confusion-and-Uncertainty.pdf.

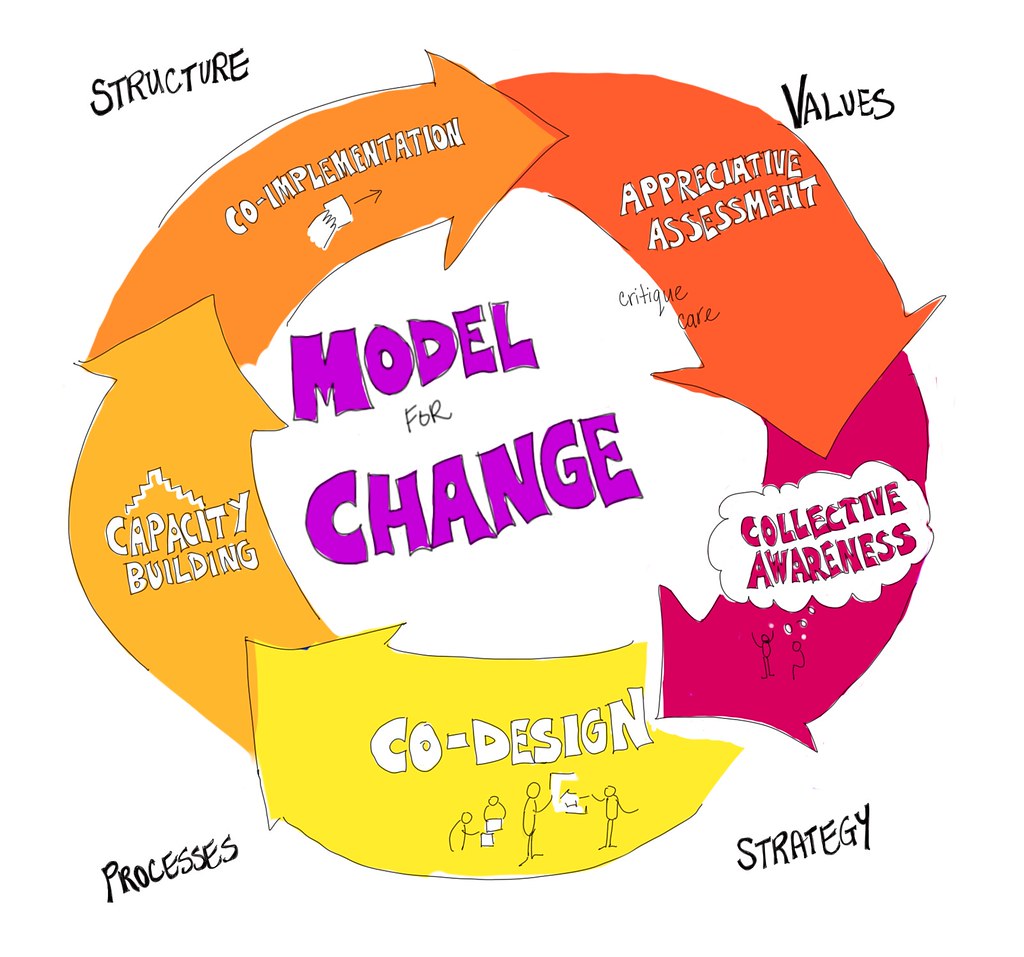

capacity building > co-implementation > appreciative assessment > collective awareness > back to co-design" width="1024" height="957">

capacity building > co-implementation > appreciative assessment > collective awareness > back to co-design" width="1024" height="957">