I

Module 1: Introduction and Overview of UDL

Authors: Nick Baker, University of Windsor; Darla Benton Kearney, Mohawk College; Christine Zaza, University of Waterloo

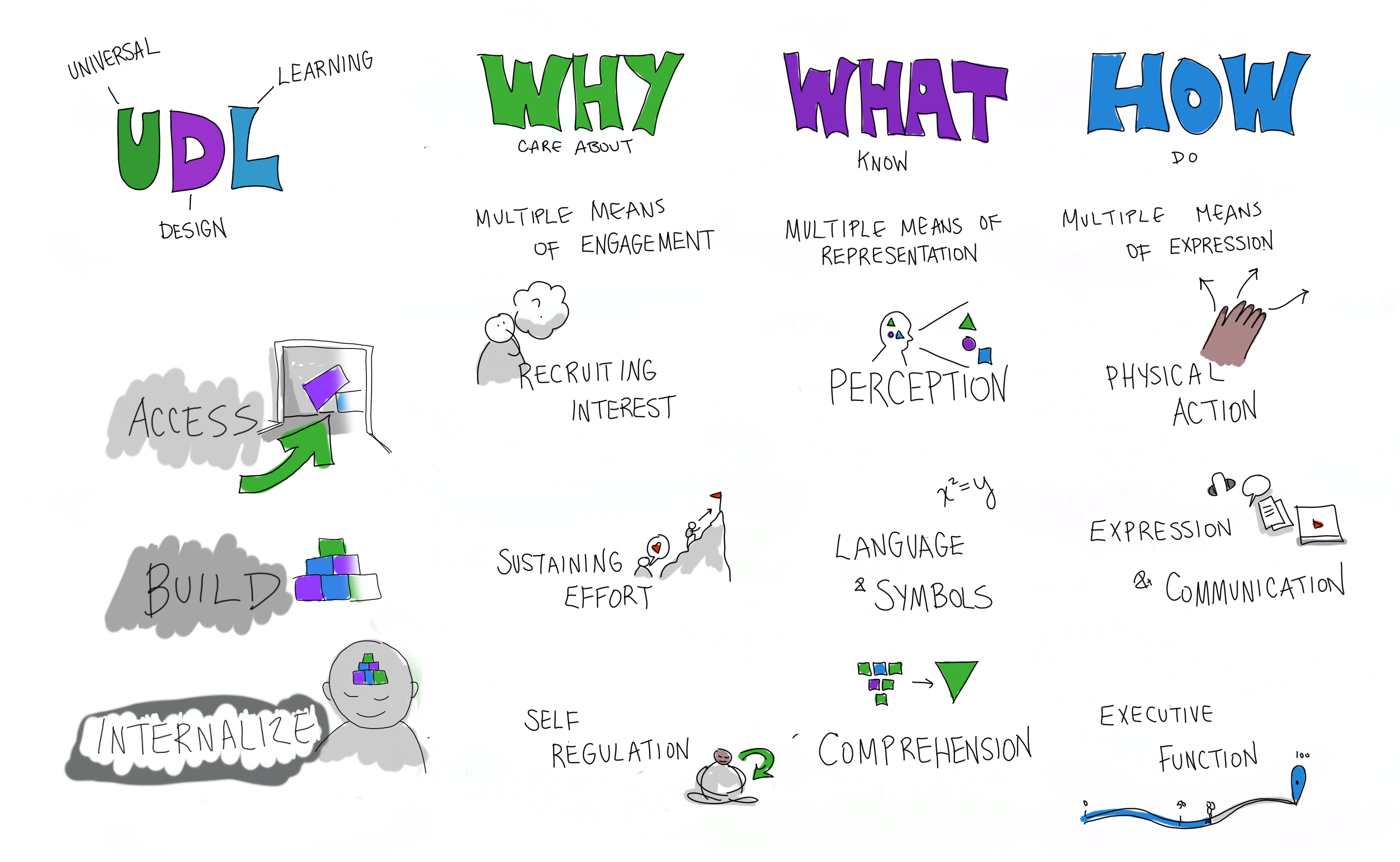

(Forsythe, 2021)

Have you ever heard of Universal Design for Learning (UDL)? What is it and why does it matter? The Introduction and Overview of UDL module gives a synopsis of UDL, including its origins and examples. This module will ensure participants have a foundational understanding of UDL with opportunities to reflect on how it can improve inclusion, equity, and access in all of our teaching and learning environments. Throughout this module, you will be asked to define and redefine what UDL might be for you as an educator and within your specific context.

Learning Outcomes

Upon successful completion of this module, you should be able to:

- Describe key elements of the UDL guidelines and their purpose

Learning Activities and Assessments

- Define and refine activity and module assessment

- Reflection questions throughout the module

- Application activity

Your responses to the learning activities and assessment will not need to be submitted in this module, but may be used as a foundation for discussions or as part of an implementation plan.

Time Commitment

Approximately 90 minutes

References

Forsythe, G. (2021). UDL Guidelines Doodle edition. [Infographic]. Flickr. https://www.flickr.com/photos/gforsythe/51592407506/ CC BY 2.0.

1.1: Origins of UDL

Concept of Universal Design

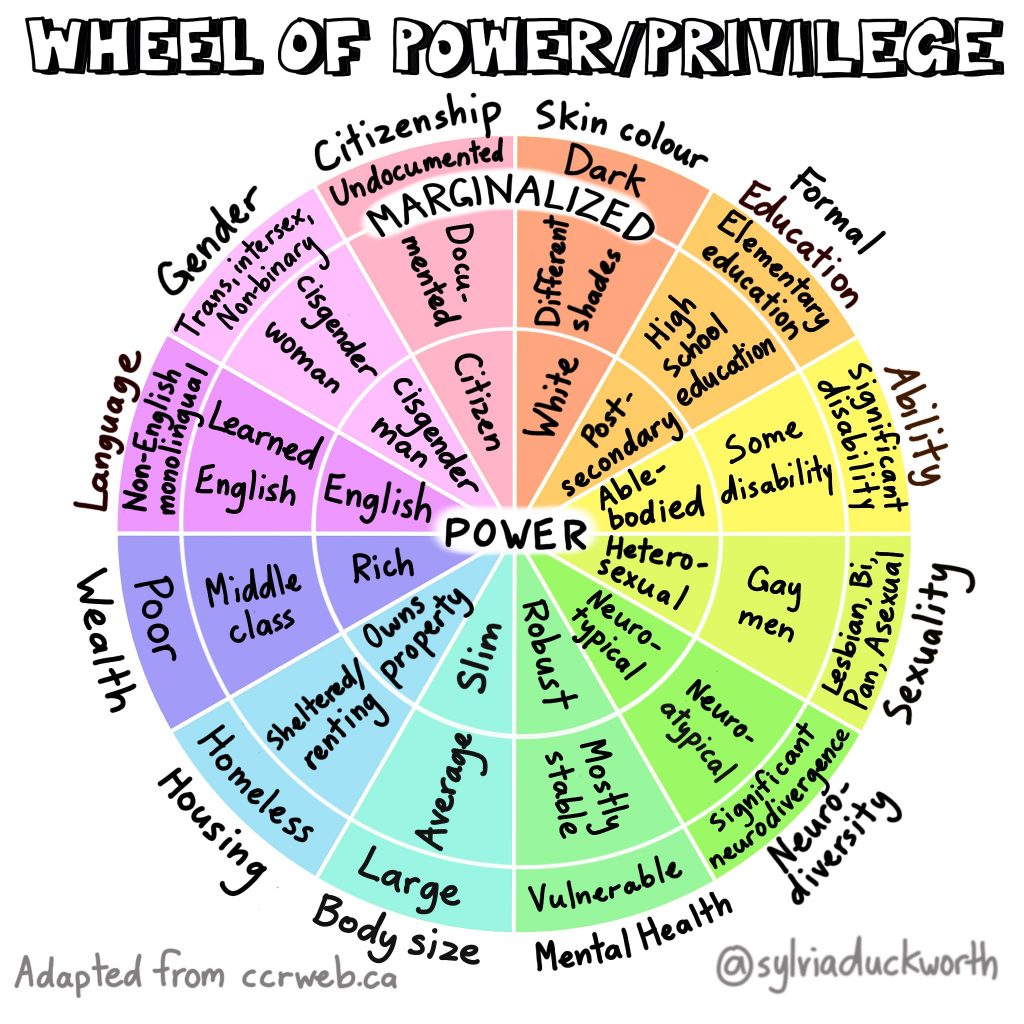

In the 1980s, architect Ronald Mace introduced the term Universal Design (UD). In its original application, UD refers to “the design of products and environments to be usable by all people, to the greatest extent possible, without the need for adaptation or specialized design” (Connell et al., 1997). For example, consider the barriers presented by entering a building that has steps up to a door with handles. Who would have difficulty accessing such a building?

Now consider a building entrance that is at ground-level entry with doors that open automatically. Who would have difficulty navigating this building?

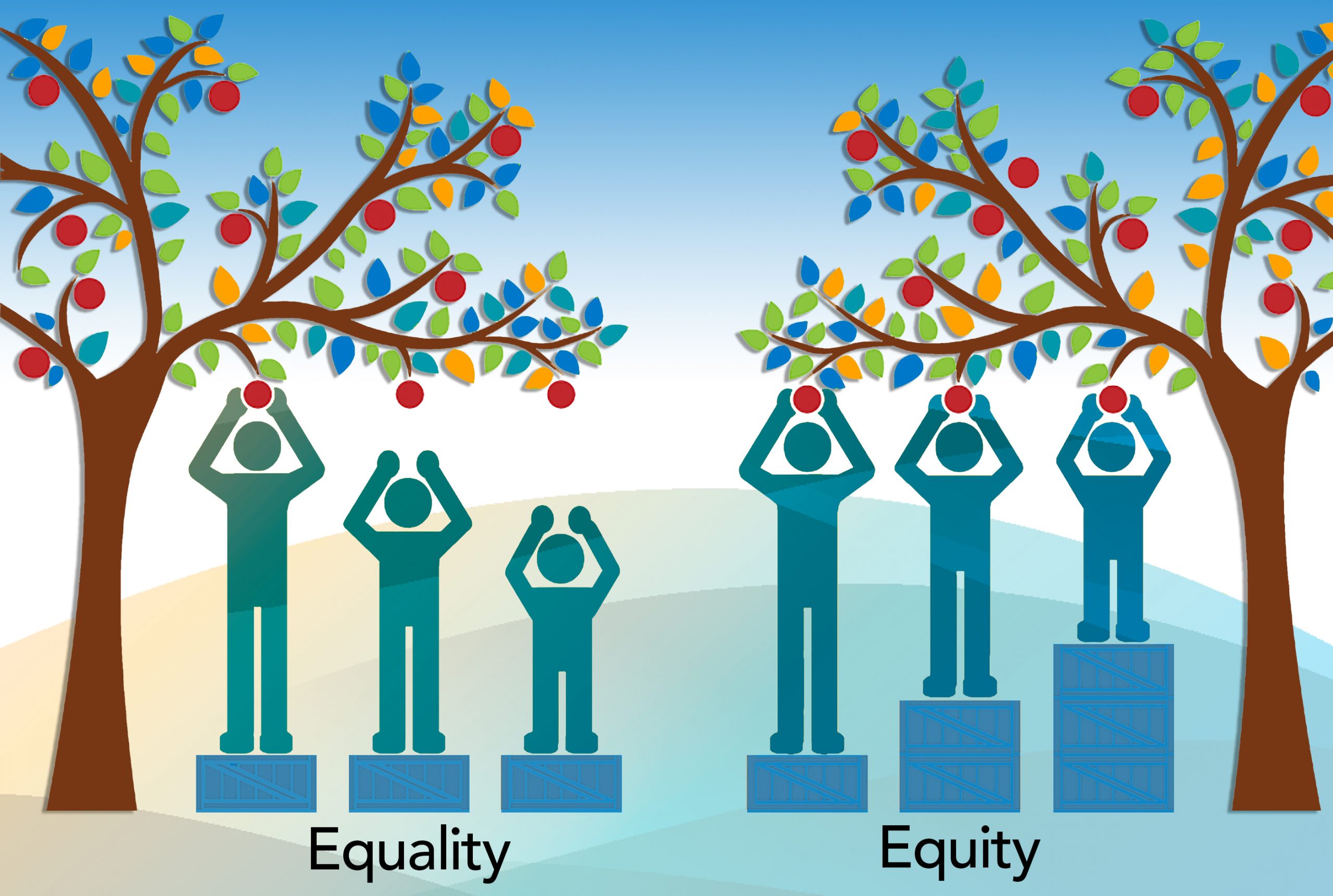

Just as stairs pose barriers in the built environment, there are barriers to learning in education. The concept of removing barriers and increasing access has been applied to the field of education with the development of various UD frameworks, including Universal Instructional Design (UID), Universal Design for Instruction (UDI), and Universal Design for Learning (UDL).

Despite their differences, inclusive instruction is the common goal of all three of these frameworks. The ultimate goal of inclusive instruction is to remove unnecessary barriers and improve access for all learners.

Universal Design for Learning

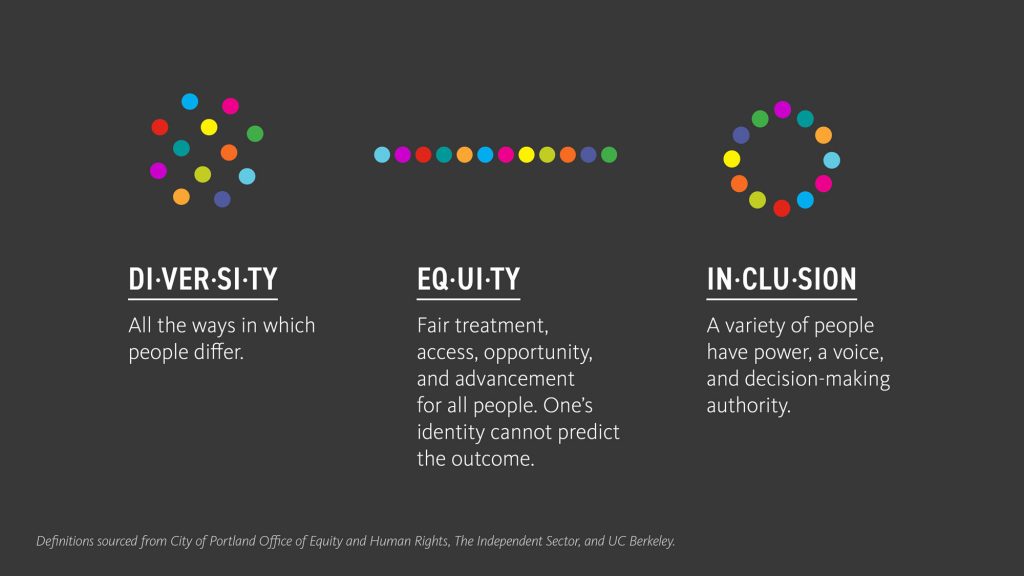

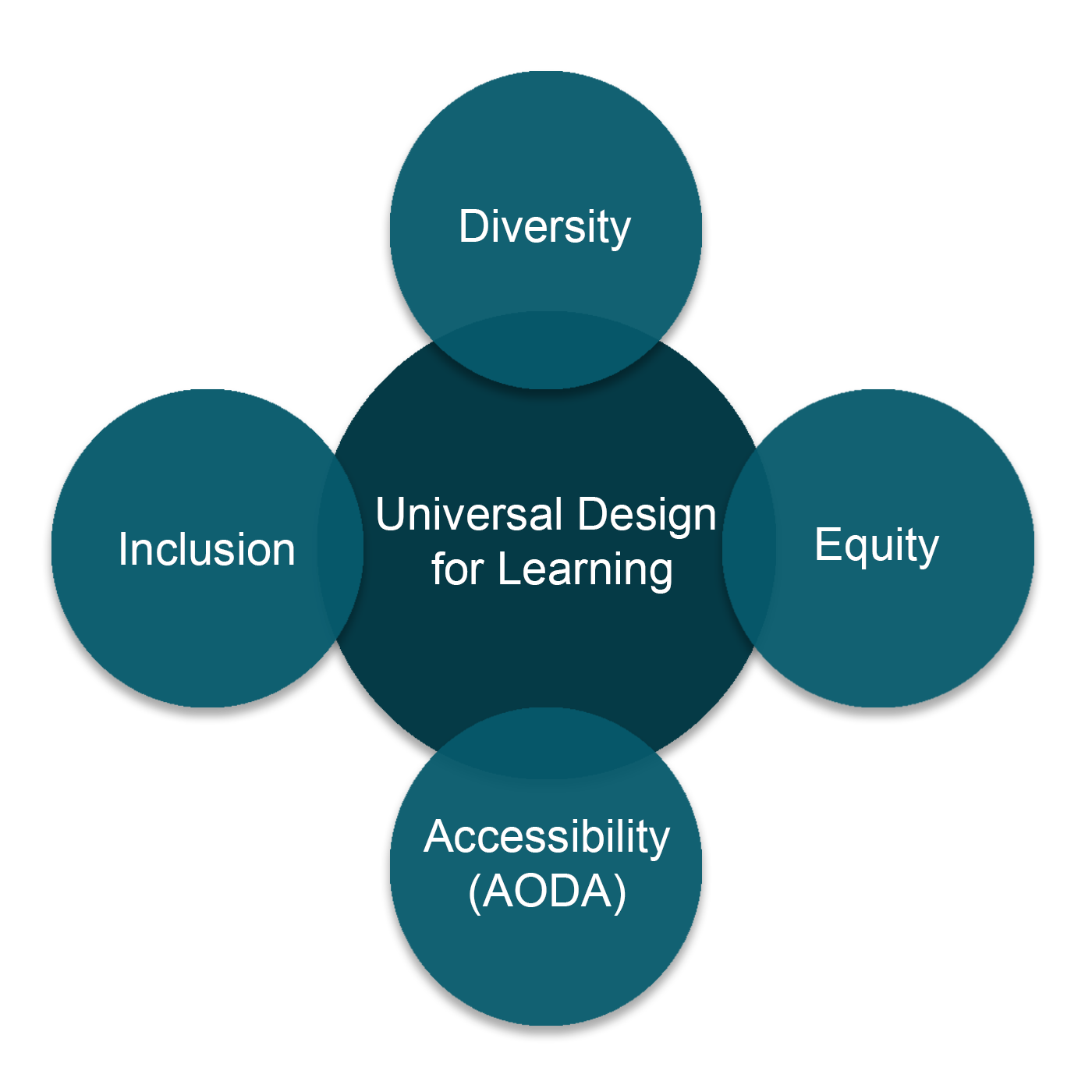

In the 1900s, David Rose, Anne Meyer, and their colleagues at the Center for Applied Special Technology (CAST) developed the UDL framework![]() , which is the only UD framework that is based on research on cognitive neuroscience (Meyer, et al. 2002; Rose, Rouhani, et al., 2013; Rose, 2016). CAST is an organization whose mission is to eliminate barriers to learning and support the development of expert learners while addressing aspects of inclusion, diversity, equity and accessibility.

, which is the only UD framework that is based on research on cognitive neuroscience (Meyer, et al. 2002; Rose, Rouhani, et al., 2013; Rose, 2016). CAST is an organization whose mission is to eliminate barriers to learning and support the development of expert learners while addressing aspects of inclusion, diversity, equity and accessibility.

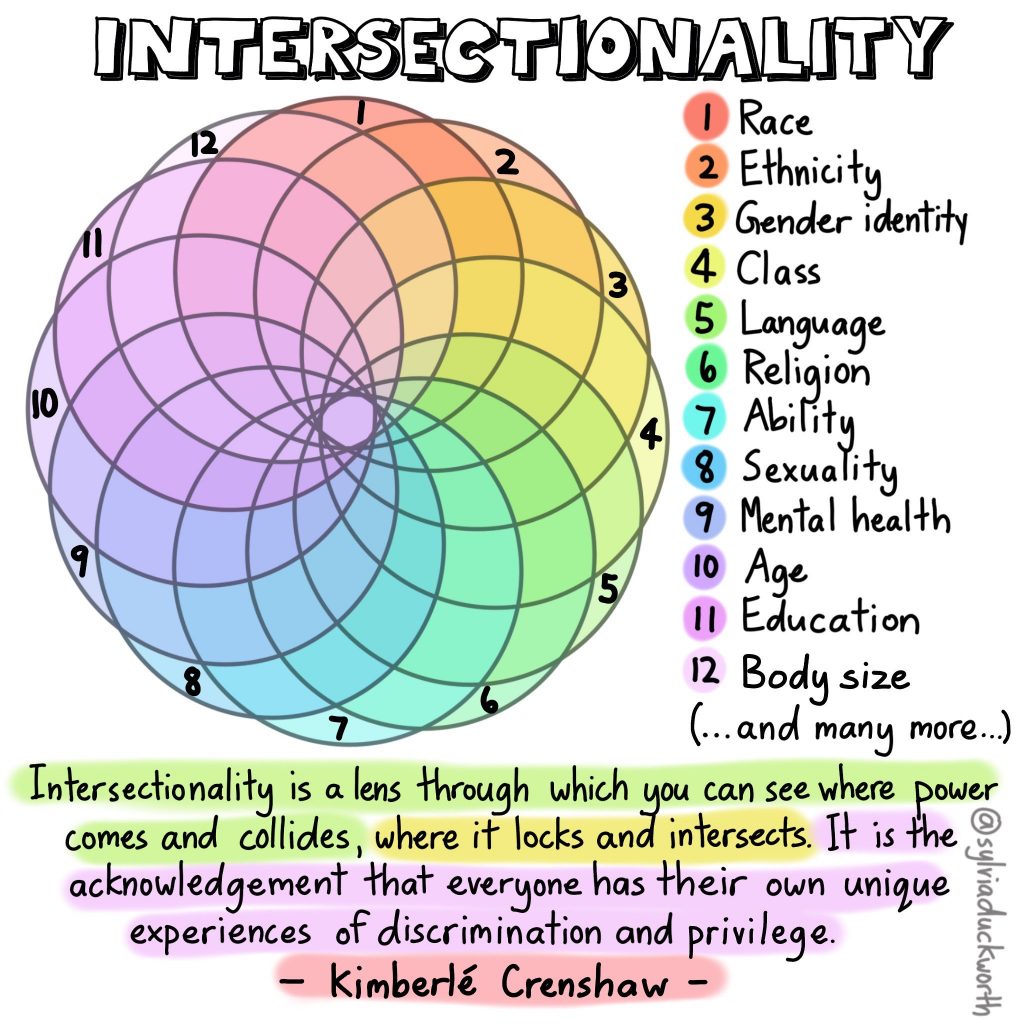

A key aspect of UDL is understanding that all learners are variable and that the “average student” simply does not exist. We cannot plan for every learner variable, but we can design, develop, and deliver our curriculum knowing our learners will have diverse needs and providing them options to ensure everyone’s needs are met.

Todd Rose explains that when organizations plan for the “average” they are not, in fact, planning to meet anyone’s needs. Education can struggle with this concept; as educators, we often design curriculum for “average” post-secondary students. Instead, if we plan to support learners at the margins, we go a long way to creating more equitable, accessible, and inclusive learning environments for all diverse student populations. Watch Todd’s video to fully appreciate the need to rid ourselves of the idea of “average”.

The TEDx (2013) video, The Myth of the Average: Todd Rose at TEDx Sonoma County [18:26],explains why we should rid ourselves of the idea of the “average”.

Once we accept that there is no average, we can start to find teaching and learning strategies to support all of our students. The UDL guidelines provide the strategies we need and offer a path for curriculum design, development and delivery that embeds equity, diversity, access and inclusion.

Activity 1: Define UDL

Define UDL as you understand it within your context. If UDL is new to you, what does the phrase “Universal Design for Learning” invoke for you? If you already use UDL principles, how do you define them in your teaching and/or learning?

You are invited to record your definition in the way that works best for you, which may include writing, drawing, creating an audio or video file, mind map or any other method that will allow you to document your ideas and refine them at the end of this module.

Alternatively, a text-based note-taking space is provided below. Any notes you take here remain entirely confidential and visible only to you. Use this space as you wish to keep track of your thoughts, learning, and activity responses. Download a text copy of your notes before moving on to the next page of the module to ensure you don’t lose any of your work!

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/universaldesignvls/?p=30#h5p-2

References

chrisinplymouth (Photographer). (2017). Automatic door [Photograph]. Flickr. https://flic.kr/p/Xmqa6m. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Connell et al. (1997). The Principles of Universal Design. NC State University. https://projects.ncsu.edu/ncsu/design/cud/about_ud/udprinciplestext.htm

Rose, D. H., Meyer, A., Strangman, N., & Rappolt, G. (2002). Teaching every student in the digital age: Universal design for learning. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Rose, L.T., Rouhani, P., & Fischer, K.W. (2013). The science of the individual. Mind, Brain, and Education, 7(3), 152-158. https://doi.org/10.1111/mbe.12021

Rose, T. (2016). The end of average: How we succeed in a world that values sameness. Harper Collins.

rvaphotodude (Photographer). (2006). Thomas Jefferson High School – Entrance [Photograph]. Flickr. https://flic.kr/p/4oQL9q. CC BY-SA 2.0.

TEDx Talks. (2013, Jun 19). The Myth of Average: Todd Rose at TEDxSonomaCounty [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/4eBmyttcfU4

1.2: UDL Guidelines

Universal Design for Learning (UDL) is a curriculum design, development, and delivery framework used to create equitable, inclusive, and accessible learning environments. UDL assumes all learning environments are diverse and that all learners have variable learning needs. UDL works to provide learning spaces (both physical and virtual) where all students can effectively learn, and demonstrate their learning while creating expert learners who are purposeful, motivated, resourceful, knowledgeable, strategic, and goal-directed.

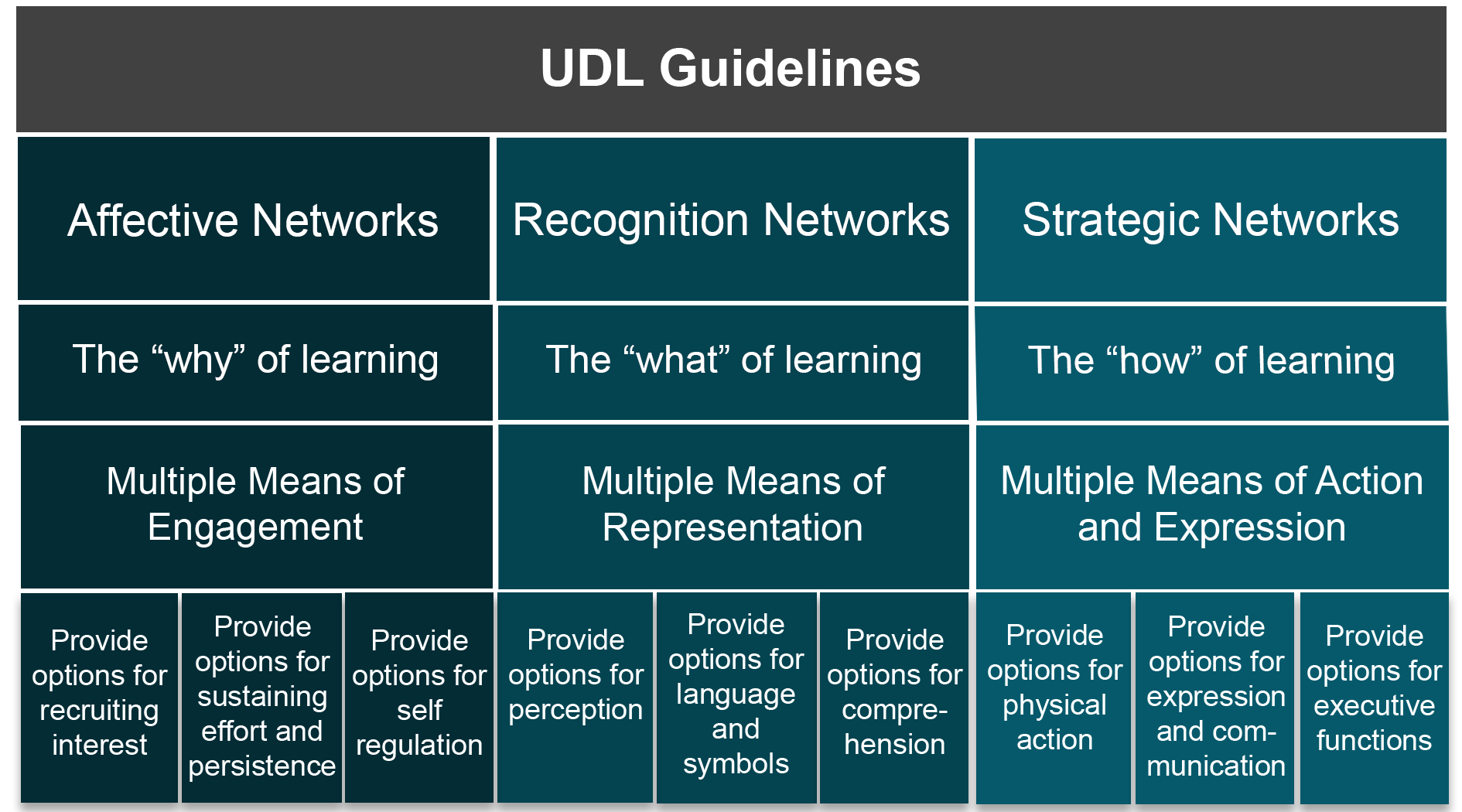

Networks

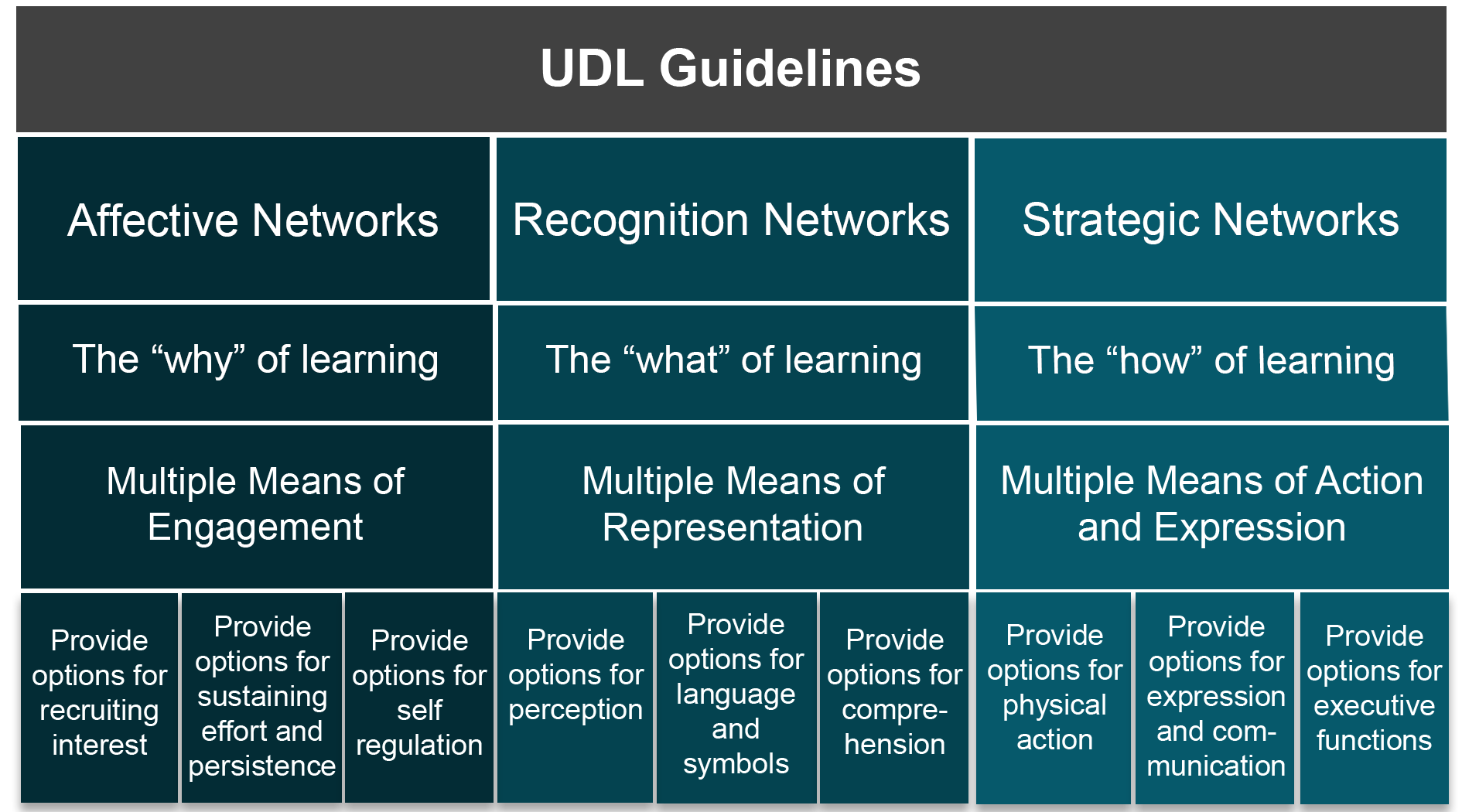

UDL guidelines are based on the three primary brain networks shown in the slides below:

- Affective networks – The “why” of learning

- Recognition networks – The “what” of learning

- Strategic networks – The “how” of learning

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/universaldesignvls/?p=37#h5p-3

(CAST, 2018)

Creating learning experiences that activate these three broad learning networks is a useful pursuit for educators as it works towards the goal of expert learning. In addition, the UDL framework reminds us that all brains are variable and that monolithic “learning styles” do not actually exist. Instead, we know that each brain is processing information in complex and variable interactions between the various networks of the brain.

Principles

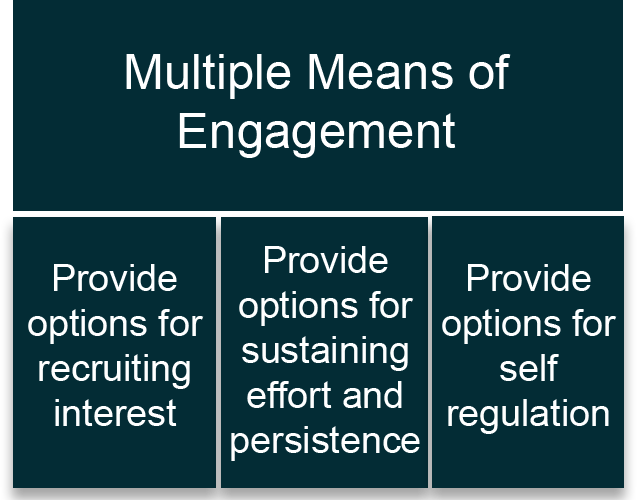

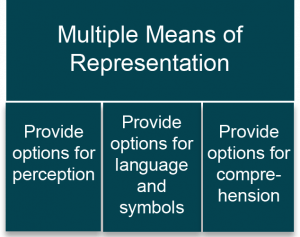

CAST has identified a series of principles to guide design, development, and delivery in practice to address each of the different networks:

- Multiple means of engagement

- Multiple means of representation

- Multiple means of action and expression

Checkpoints

Each network contains checkpoints (three for each network making nine in total) that emphasize learner diversity that could either present barriers to, or opportunities for, learning. The checkpoints for each network are as follows:

- Multiple Means of Engagement

- Options for recruiting interest

- Options for sustaining effort and persistence

- Options for self-regulation

- Multiple Means of Representation

- Options for perception

- Options for language, math and symbols

- Options for comprehension

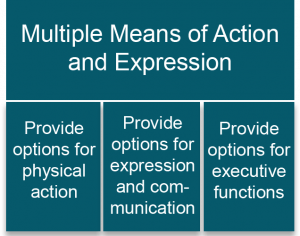

- Multiple Means of Action and Expression

- Options for physical action

- Options for expression and communication

- Options for executive functions

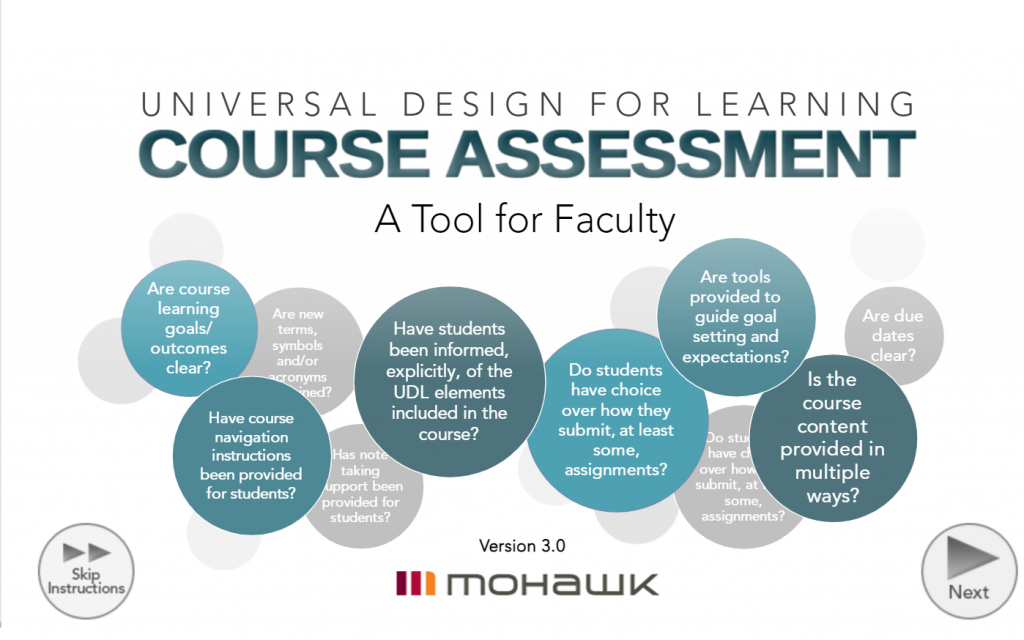

The guidelines are not prescriptive, but instead offer informed suggestions that can be used in any program, course or learning environment to support masterful learning and accurate assessment. Some post-secondary institutions use a streamlined version of the UDL framework to provide more flexibility for application (as shown below).

The video, What is UDL? [2:45] by Mohawk College (2019), explains how all of the UDL components work together.

One or more interactive elements has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view them online here: https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/universaldesignvls/?p=37

Transcript of What is UDL? (PDF)![]()

The UDL Guidelines (CAST)

Some UDL implementers prefer to use a PDF version of the UDL Guidelines![]() from CAST that offer additional elements for each checkpoint. To learn more about the UDL Guidelines from CAST, consider reviewing the interactive version and accompanying resources on The UDL Guidelines

from CAST that offer additional elements for each checkpoint. To learn more about the UDL Guidelines from CAST, consider reviewing the interactive version and accompanying resources on The UDL Guidelines![]() website. The UDL Guidelines are consistently informed by user feedback and ongoing research, meaning the guidelines used in UDL for IDEA have been revised a number of times.

website. The UDL Guidelines are consistently informed by user feedback and ongoing research, meaning the guidelines used in UDL for IDEA have been revised a number of times.

Activity 2: Reflect

- At this point, are there specific topics related to UDL that you would like to learn more about?

- Is it possible to design a learning environment that works for all learners?

- What is one thing you realize you have done in your past teaching that would not fit the UDL Guidelines?

You are invited to reflect in the way that works best for you, which may include writing, drawing, creating an audio or video file, mind map or any other method that will allow you to reflect and refer back to your thoughts.

Alternatively, a text-based note-taking space is provided below. Any notes you take here remain entirely confidential and visible only to you. Use this space as you wish to keep track of your thoughts, learning, and activity responses. Download a text copy of your notes before moving on to the next page of the module to ensure you don’t lose any of your work!

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/universaldesignvls/?p=37#h5p-2

References

CAST (2018). UDL & the Learning Brain [Graphic]. https://www.cast.org/products-services/resources/2018/udl-learning-brain-neuroscience

CAST (2018). Universal Design for Learning Guidelines version 2.2 [Chart]. http://udlguidelines.cast.org

Mohawk College. (2019). Universal Design for Learning [Graphic]. http://www.mohawkcollege.ca/employees/centre-for-teaching-learning/universal-design-for-learning

Mohawk College. (2019). UDL with CTL [Video]. https://www.mohawkcollege.ca/employees/centre-for-teaching-learning/universal-design-for-learning

1.3: Examples of UDL

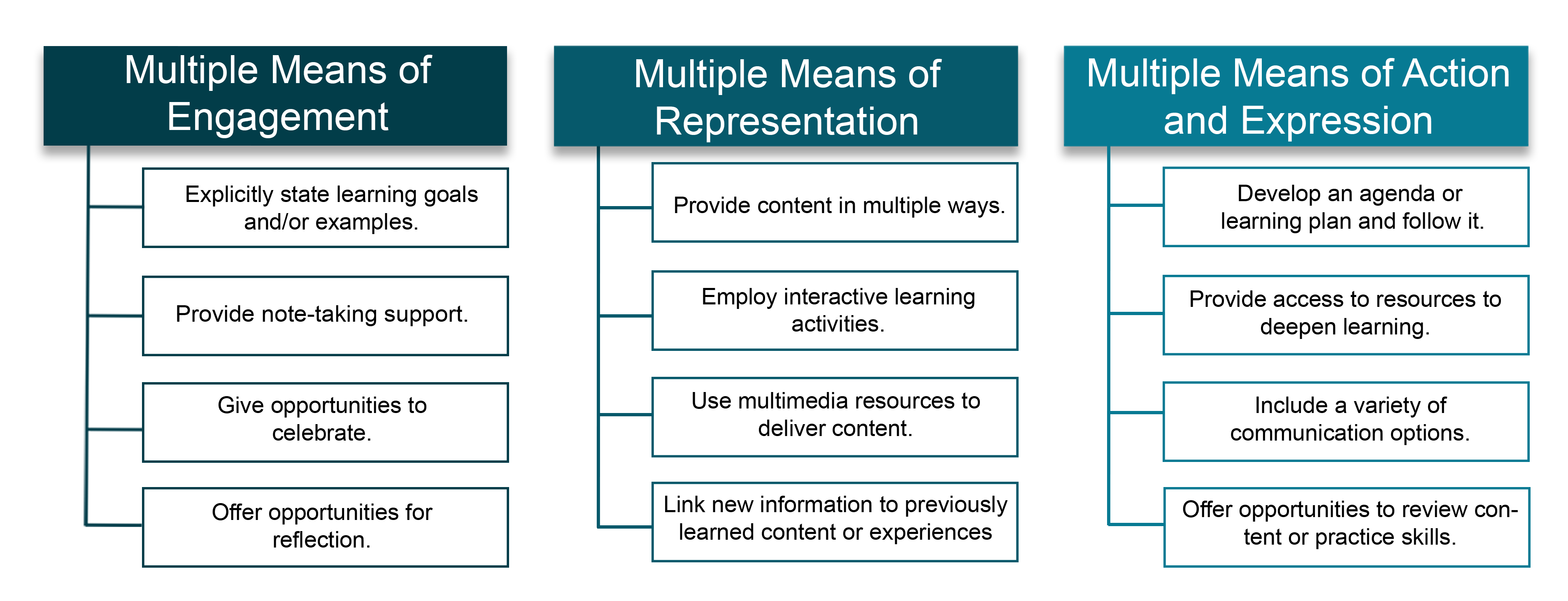

We have offered a couple of examples of Universal Design (UD) in the previous topic of this module, but what does UDL look like? The following are some general examples organized by the UDL Guideline principles. (Mohawk College, 2021).

You may find it helpful to see what UDL can look like based on your teaching and learning space. Here are some examples of UDL in a variety of learning environments. To view a higher resolution version of the graphic below, right-click on the graphic and choose “open image in a new tab.”

Traditional Learning Spaces

There are many names for what we are calling “traditional” learning spaces; you may refer to these learning environments as face-to-face, in-person, or in-class. Whatever label works for you, the examples below outline what UDL can look like when your learners are physically present in a defined classroom space and content is being delivered synchronously:

- Provide opportunities for learners to move in the classroom space to form groups or pairs to complete learning activities

- Make time throughout the class/session to stop and have learners reflect

- Give options for how learners can ask questions, which may include raising hands, using a backchannel or submitting written questions

- Offer assessments that provide time and space for prompt feedback (from the educator or peers) within the lesson

Online Learning Environments

For the purposes of this module, “online” learning environments are defined as content delivered and assessed (as required), fully technology-enabled and without any traditional learning space elements. The examples below outline what UDL can look like in these online learning environments where content may be being delivered synchronously and/or asynchronously:

- Provide opportunities to review content asynchronously

- Offer options for learning participation, which may include using chat functions, discussing topics through the learning management system, and asking questions on screen

- Develop interactive learning activities such as polls, check-in questions, discussion topics for breakout rooms

- Proactively include additional time and/or attempts on assessments for all learners

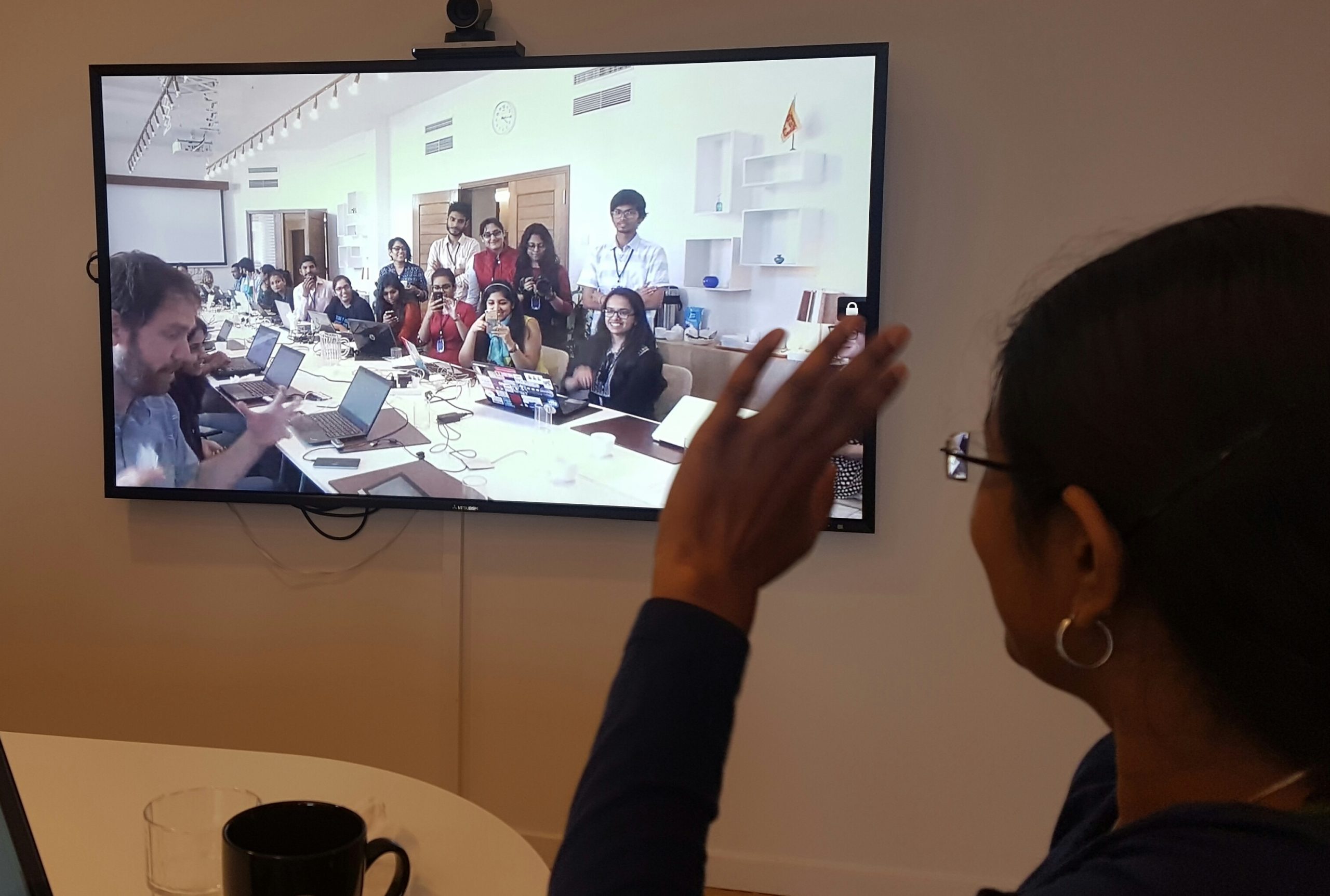

Blended or Technology-Mediated Learning

Blended or technology-mediated learning spaces are, for the purposes of this module, defined as a combination of traditional and online learning environments where content may be delivered synchronously and/or asynchronously. The examples below outline how UDL can be implemented in these teaching and learning environments:

- Offer multimedia resources online that solidify concepts taught in the traditional class environment

- Include clear navigation instructions so learners can manage both learning spaces

- Suggest communication options for in-person and online

- Provide assessment opportunities that take place in the “traditional” learning space, as well as online to ensure a variety of not only assessment methods, but also environments

You will notice that many of these examples can be adapted to any teaching and learning environment. You will also notice that UDL does not need to be large-scale projects or require you to dismantle a course. UDL can be small changes over time, offering more options when and where you can, reflecting on the impact of those changes, and continuously improving your teaching and your students’ learning. The end result will be a more inclusive, equitable and accessible learning space for all of your learners.

Activity 3: Minimizing Barriers to Hyflex Learning

“Hybrid flexible” or hyflex is defined as a course design and delivery approach that “combines face-to-face (F2F) and online learning”, with “Each class session and learning activity…offered in-person, synchronously online, and asynchronously online” HyFlex allows the learner to determine how to participate given students flexibility and the capacity to engage with the course content regardless of location or time (EDUCAUSE, 2020).

Imagine you are teaching a hyflex course, how will you apply UDL principles to minimize the following barriers?

- Engagement: Online students are missing the social component of in-person learning

- Representation: Only using a PowerPoint to present new information

- Action & Expression: Only multiple choice and written response to assess students’ learning

You are invited to reflect in the way that works best for you, which may include writing, drawing, creating an audio or video file, mind map or any other method that will allow you to reflect and refer back to your thoughts.

Alternatively, a text-based note-taking space is provided below. Any notes you take here remain entirely confidential and visible only to you. Use this space as you wish to keep track of your thoughts, learning, and activity responses. Download a text copy of your notes before moving on to the next page of the module to ensure you don’t lose any of your work!

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/universaldesignvls/?p=43#h5p-2

References

EDUCAUSE. (2020). 7 things you should know about the hyflex course model. https://library.educause.edu/resources/2020/7/7-things-you-should-know-about-the-hyflex-course-model

Benton Kearney, D. (2021). UDL Examples [Graphic]. UDL: Getting Started Presentation, Mohawk College.

Mörtsell, S. (2017). Netha and Video call Sweden India edit-a-thon [Photograph]. Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=56800623. CC BY-SA 4.0.

teddy-rised (Photographer). (2008). That Huge Lecture Theatre! [Photograph]. Flickr. https://flic.kr/p/5hJ8dN. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

1.4: Assessment and Resources

Module Activity: Refine Your Definition

Using your definition from the beginning of this module, refine your definition of UDL for your context. It may be helpful for your revised definition to include audience, environment, purpose and specific applications as they apply to your work.

You are invited to reflect in the way that works best for you, which may include writing, drawing, creating an audio or video file, mind map or any other method that will allow you to reflect and refer back to your thoughts.

Alternatively, a text-based note-taking space is provided below. Any notes you take here remain entirely confidential and visible only to you. Use this space as you wish to keep track of your thoughts, learning, and activity responses. Download a text copy of your notes before moving on to the next page of the module to ensure you don’t lose any of your work!

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/universaldesignvls/?p=45#h5p-2

Further Learning

The following are some resources to deepen your learning about UDL and its implementation:

- The Centre for Applied Special Technology (CAST) is the conceptual home of UDL. The About Universal Design for Learning

website offers a wealth of resources for both the new and seasoned UDL implementer.

website offers a wealth of resources for both the new and seasoned UDL implementer. - The ThinkUDL podcast

discusses the implementation of UDL in higher education with educators who are designing and developing their curriculum with learner variability as their focus. The examples are relevant, and the discussion is always interesting.

discusses the implementation of UDL in higher education with educators who are designing and developing their curriculum with learner variability as their focus. The examples are relevant, and the discussion is always interesting. - A portion of the UDL with CTL video was included earlier in the module. You are welcome to access the entire video on Mohawk College’s Universal Design for Learning

webpage.

webpage.