Introduction to Field Placement by Melanie Jones is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Introduction to Field Placement by Melanie Jones is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

1

This Introduction to Field Placement resource includes three interactive online modules designed to prepare community services students, specifically Child and Youth Care students, for field placement. The modules are:

Each module is designed to augment the content delivered in students’ face-to-face classes. Students will work through the material online and then connect their learning to in-class discussions. With this resource, learners will practice new skills, techniques, and critical thinking in a virtual environment. The modules and interactive activities have the potential to improve the learners’ retention of knowledge and promote active learning, problem-solving, and critical thinking skills.

Contact

2

Acknowledgements

This open textbook was overseen by Sault College.

The development of this open educational resource was funded by the Province of Ontario and eCampusOntario (OOLC).

A special thank-you goes to Sault College Child and Youth Care students Nadia Grbich, Elicia O’Brien, and Sarah Tremelling for providing me with feedback and guidance along this journey. Your student perspective was invaluable and provided me with the assurance I was on the right track throughout the creation of this resource.

This resource would never have come to fruition without the incredible support of Amanda Baker-Robinson, Instructional Designer extraordinaire! Your knowledge of Universal Design for Learning, Pressbooks, and Accessibility has made this resource one that I am very proud to use with my students. Thank you so much for your ongoing support, professionalism, and encouragement!

To Rhett Andrew, Language and Communication Department Coordinator and Faculty. Thank you so very much for your attention to detail and support in editing this resource for me. I would never have picked up on all the missing Oxford commas and citation errors without you.

Chi Miigwetch to Carolyn Hepburn, Dean of the School of Indigenous Studies and Academic Upgrading. I greatly appreciate all the times you met with me, provided me with suggested resources/contacts, and supported my process of ensuring I was being respectful and accurate with the Indigenous-specific content for this resource.

I would also like to acknowledge Community Placement supervisors Denise Berg, Jenna Polutanovich, and Chantelle Day for providing me with their insight into the supervisor perspective of CYC student placements and feedback on how to best prepare students for placement.

Thank you also to my fantastic work colleagues: Child and Youth Care faculty Donna Mansfield, Shelly Nelson-Bond, Lisa Guzzo, and Sandy MacDonald. Without your feedback, patience, kindness, and support, the development of this resource might not have happened!

Last, but certainly not least, thank you to my incredible partner in life, Dustin Jones, and my two wonderful children for putting up with me this past year! The switch to working remotely had its ups and downs but you have been so patient and understanding of my work. I definitely couldn’t have done this without your support and encouragement.

Melanie Jones

3

We begin this resource by acknowledging that Sault College is located in the Robinson Huron Treaty territory, and are grateful to Mother Earth for providing us the land, water, air, and food needed to sustain all life, and we acknowledge Indigenous Peoples as the original stewards of this land who have lived in harmony and in respect with all creation. As we are all relations, it is important to recognize this interconnected relationship with one another and our obligation to respect the land that has nourished, healed, protected, and embraced us. We honour Obadjiwan (Batchewana First Nation) and Ketegaunseebee (Garden River First Nation) as the original caretakers of the land that Sault College is situated on and acknowledge the contributions of the historical Metis Nation of SSM in the stewardship of this territory.

Sault College has been fortunate to have the opportunity to work with members of Indigenous communities who have shared their knowledge and guidance over the years. We acknowledge the significance of these relationships to undertake this work in providing us with the insight and direction required. It is through developing these relationships that we were able to engage in conversations and honour the stories shared with us by Indigenous citizens and community members.

I

An important task in preparing for your first level of field placement is to reflect on your own perspective of professionalism. Ask yourself questions such as:

Your Turn

The Council of Canadian Child and Youth Care Associations (CCCYCA) defines Child and Youth Care (CYC) practice as one that

focuses on the developmental needs of children, youth, and families within the space of time of their daily lives. People who work in the field are dedicated to improving the lives of children, youth and families through an active and engaged recognition of the competence and value of the people with whom they work. (as cited in Stuart & Fryer, 2021, p. 6)

To be able to do this kind of work, one requires an understanding of what Child and Youth Care involves, as well as a level of professionalism and ethical behaviour that is in line with the values of Child and Youth Care.

According to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary (n.d.), professionalism refers to “the conduct, aims, or qualities that characterize or mark a profession or a professional person” (para. 1). Professionalism is profoundly linked with the development of a respectful workplace and a shared standard of norms and behaviours among people in the same field.

This section will review the competencies under the professional domain identified by the Child and Youth Care Certification Board (CYCCBB). The CYCCBB (2016a) states:

Professional practitioners are generative and flexible; they are self-directed and have a high degree of personal initiative. Their performance is consistently reliable. They function effectively both independently and as a team member. Professional practitioners are knowledgeable about what constitutes a profession and engage in professional and personal development and self-care. The professional practitioner is aware of the function of professional ethics and uses professional ethics to guide and enhance practice and advocates effectively for children, youth, families, and the profession. (para. 1)

After reviewing the CYCCBB Professional competencies, this module will continue to explore ethics and ethical practices in CYC, including scenarios to reflect on and work through. Next, there will be a chapter that looks at personal and professional boundaries, followed by an introductory look at supervision for entry-level CYC workers.

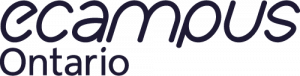

’The CYCCB (2016) brings together a broad range of CYC practitioners from various practice settings and geographical locations to “promote widely supported standards of practice coupled with research-based competence demonstration” (para. 1). The CYCCB (2010) have identified CYC competencies organized across five domains:

To prepare for your first level of Community Practicum, the first step is to have a general understanding of what professional CYC practice involves. The following is a brief overview of each of the competencies found in the professionalism domain, which the Association for Child and Youth Care Practice and the Child and Youth Care Certification Board have identified as necessary for professional CYC practice.

CYC Student Sarah Tremelling states “Remember that even as a student, demonstrating professionalism in your placement is important. Be aware of the placement’s expectations such as the dress code” (personal communication, November 22, 2021).

The first competency identified is having an awareness of the profession. It is imperative to know how and where to access professional literature and information about local and professional activities (CYCCB, 2010). Awareness of the profession also involves being aware of current professional issues, future trends and challenges in one’s area of special interest, and contributing to the ongoing development of the field (CYCCB, 2010). For students in the CYC program, this awareness began in your first semester and will continue to grow throughout the rest of the program; however, it is also each student’s responsibility to ensure ongoing awareness of the profession as they continue their CYC education.

One way you can keep up to date with the profession is to become a member of the Ontario Association of Child and Youth Care (OACYC), the professional association in Ontario representing Child and Youth Care Practitioners (CYCP). The OACYC (2019) provides professional standards, regulations, support, and a Code of Ethics to its members, “thus ensuring integrity, accountability, and excellence” (para. 3).

Values are integral to professional development and behaviour. It is important to be able to identify your own personal and professional values and know the implications of those values on one’s practice. A CYCP’s own personal and professional values, beliefs, and attitudes have significant influence on interactions. As part of this domain, you should be able to “state a philosophy of practice that provides guiding principles for the design, delivery, and management of services” (CYCCB, 2010, p. 11).

Professional development and behaviour as a competency will require you to reflect on your own practice and performance by identifying needs for professional growth as well as being able to give and receive constructive feedback.

On-the-job performance of productive work habits, such as knowing and conforming to workplace expectations (e.g., attendance, punctuality, and workload management) is a key component to a CYC’s professional development and behaviour. This competency also includes the cultivation of professional physical appearance (e.g., good hygiene, neat grooming, and appropriate attire) and behaviour that reflect an awareness of yourself as a professional and a member of the organization.

As professionals, it is important for CYCs to recognize and assess their own needs and feelings and ensure they can keep those in perspective when involved with clients. Furthermore, a practitioner should also be modelling appropriate interpersonal boundaries.

Child and Youth Care Practitioners should also keep themselves up to date with any developments in foundational and specialized areas of expertise, and they should show an involvement in finding and participating in professional development activities.

Having an awareness of self, including personal strengths and limitations, as well as an ability to separate personal from professional issues, are key components to the Personal Development and Self-Care subdomain. You should also be sure to utilize wellness practices in your life, practice stress management, and build and use a support network. The third module of this online resource will go into much more depth on self-care and personal development.

The Standards for Practice of North American Child and Youth Care Professionals are a set of principles and standards (Code of Ethics) to provide a framework for ethical thinking and decision making in Child and Youth Care practice. According to the CYCCB (2010), as a professional CYC, you must be able to

CYC Professional Ethics will be further discussed on the next page of this module.

As part of CYC professional competencies, the CYCCB (2010) states that an awareness of law and regulations is imperative. All CYCs should access and apply relevant municipal, provincial, and federal laws, licensing regulations, and public policy. They also need to understand their lawful duty to report abuse and neglect and the consequences of failure to report. CYCs should be able to define informed consent and how it is relevant to specific practice settings, and they should be able to use proper procedures for reporting and correcting non-compliance of laws and regulations (CYCCB, 2010).

Learn More

Read about “Recognizing Red Flags of Child Abuse” (link opens in new page) and watch the video provided for more information about what indicators should prompt you to make a report.

When displaying professional behaviour, a CYC should demonstrate knowledge and skills in use of advocacy, and access information on the rights of children, youth, and families, including the United Nations (1989) Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC). A professional CYC should, in relevant settings, be able to describe and advocate for these rights (CYCCB, 2010). Describing and advocating for safeguards for protection from abuse—including institutional, organizational and/or workplace abuse—is also imperative in this competency. The final area of this competency is to be able to advocate for protection of children from systemic abuse, mistreatment, and exploitation (CYCCB, 2010).

Apply Your Learning

Work through the following five scenarios and judge whether the fictional CYC practitioner is acting professionally or not.

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/introtoplacement/?p=124#h5p-6

Ethics are the principles of conduct governing an individual or group. As the University of Kansas Center for Community Health and Development (n.d.) puts it, ethics means:

To gain some additional insight into what ethics are, and what they look like in practice, watch “What is Ethics?” by The Ethics Centre (2020). Make sure that you are able to answer the questions below after you finish watching the video.

To access a transcript for this video, please click Watch on YouTube.

Video Questions

After watching the video above, work through the following questions:

Bring your thoughts with you to class for discussion.

The OACYC (2017) Code of Ethics is a set of standards for professional practice and guides Child and Youth Care professionals to make good decisions in their work. CYCs have the responsibility to strive for high standards of professional conduct, and the CYC code of ethics supports them in doing so. As identified in the previous section, professional ethics is a critical component to professional CYC competency. The CYCCB (2010) Standards of Practice in North American Child and Youth Care Professionals identifies that all CYCs must ensure responsibility for self; responsibility to children, youth, and families; responsibility to the employer and/or employing organization; responsibility to the profession; and responsibility to the community.

Why Do Ethics Matter in Child and Youth Care?

According to Ricks (1994), “because our personal/professional values are nested in and draw heavily on cultural values, we remain oblivious and unaware of how present our values really are and the extent to which they affect our child and youth care practice” (para. 2). It is imperative that CYCs regularly reflect on their personal and professional values and beliefs, and that they understand there may be potential dilemmas they face if working with someone of different beliefs. When facing these dilemmas, Ricks advises the following:

The first step for child and youth care workers . . . is to become aware of the contradictions between what is and what they think should be. The second step is to figure out what accounts for the difference. The differences might be that the rules are not known, or that the rules are known and not being followed. Alternately, the difference might be the rules are different and the rules are different because the beliefs and values are different. (para. 8)

Once you are more aware of these differences and how they might impact your work as a CYC, the next step is to familiarize yourself with the Standards for Practice of North American Child & Youth Care Professionals. The code does not provide simple answers to the complex dilemmas that we might face when working with children, youth, and families. It does, however, provide a framework for professional CYCs to look at a variety of possibilities to complex dilemmas, and it gives teams an opportunity to provide input from diverse viewpoints while determining the best approach (Winfield, 2003). This code of ethics is intended to be used in combination with sound professional judgement and consultation to find a course of action that is consistent with the spirit and intent of its principles.

Click on the following items to get an overview of each of the areas of the Child and Youth Care Professional code of ethics:

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/introtoplacement/?p=126#h5p-3

Apply Your Learning

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/introtoplacement/?p=126#h5p-5

“Bring your best self! Show up, be prepared, maintain healthy boundaries, and ask for support when you need it. Be curious and know that you are at the beginning stage of learning what is required of you in this field” (Donna Mansfield, Sault College CYC Program Faculty and College Placement Supervisor)

A key component in professional Child and Youth Care practice is boundaries, as boundaries establish the basis for the therapeutic relationship. According to the Oxford Learner’s Dictionary (n.d.), a boundary is “the farthest limit of something; the limit of what is possible or acceptable” (para. 1). A therapeutic relationship is a planned, goal-directed connection between a CYC and a child, youth and/or family for the purpose of providing care in order to meet the therapeutic needs of the client (Fox, 2019).

Boundaries can be professional or personal. Professional boundaries are usually covered by professional standards like the Code of Ethics, while personal boundaries may be less explicit—they may include physical, emotional, and mental limitations, which CYCs adopt to protect themselves from becoming overly-invested in their clients’ lives.

Learn More

“Professional Boundaries in Health-Care Relationships” (link opens in new page) is an excellent online article about boundaries and boundary violations from the College of Psychologists of Ontario (n.d.). Although this article was written with psychologists in mind, much of it directly applies to any client-carer relationship.

When you look at the definition of boundaries as it relates to CYC practice, you can imagine that there wouldn’t necessarily be rigid, set boundaries that can be set for every situation. As CYC practice is relationally based, these boundaries are imperative, yet quite difficult, to define, as the role of a CYC varies immensely depending on many factors. Conrad et al. emphasize the challenge of finding balance in CYC work with regards to boundaries:

Child and youth care (CYC) practitioners strive to find a balance between (a) caring about young people they work with in over-involved, dependence-creating ways, as they are genuinely moved by their life stories and current needs, and (b) not caring enough as they defend themselves against burn-out [sic], secondary traumatic stress, and compassion fatigue. (as cited in Davidson, 2004, para. 1)

Several factors influence what professional boundaries might look like, such as “the needs of the young person, the role of the professional, the quality and depth of the relationship with the young person, the mandate of the agency, the physical construction of the setting, the size of the community and the cultural context” (Davidson, 2004, para. 2). All these factors can make simple, pre-prescribed answers difficult to apply to all circumstances, hence the importance of supervision and self-reflection/awareness.

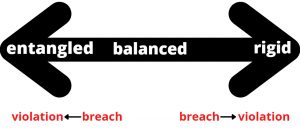

The Professional Relationship Boundaries Continuum (Davidson, 2004) below refers to “professionals’ attitudes toward emotional connections with, and involvement in[,] the lives of young people and their families in light of the position of trust and power that the professionals are privileged to hold” (para. 3). This framework is not perfect, but it can be a starting place when having discussions regarding professional boundaries in relational CYC practice.

This continuum illustrates the range of professional boundaries, with one extreme including entangled boundaries and the other extreme being rigid boundaries. A balanced approach is the most desirable option. In Davidson’s (2004) words:

The goal for professional CYCs is to find a way to ensure that professional relationships fall in the mid-range of this continuum so that relationships are balanced and no harm is done to the child, youth and/or family the CYC is working with. As you become more involved in the CYC program and placements, you will begin to recognize where you fall regarding boundaries with the children, youth, and families you work with. Each situation you find yourself in will involve a reflection on personal and professional boundaries to ensure you are providing the best care possible.

Being able to gradually develop boundary awareness, “the ability to be reflective and objectively evaluative about the need for closeness or distance in a relationship” (Mann-Feder, 2021, p. 140), is imperative. As this skill is developed, it allows for the CYC to better reflect on relational dynamics and set appropriate boundaries in each unique situation.

As part of being a CYC in training, it is important for you to understand the concept of supervision, as it is a key element of training for most helping professionals. Supervision, as it relates to child and youth care, can be defined as “the relationship of a person assigned the role of supervisor, mentor, team, or individual for the purpose of supporting your development as a CYCP” (Fraser & Ventrella, 2019, p. 222). Fox (2019) states that supervisors in any field have three primary roles:

These roles are ultimately the responsibility of the placement supervisor; however, the CYC student should also be active in ensuring appropriate supervision occurs. Charles and Garfat (2016) remind us that CYCs need to know they are important and valued, that their work is meaningful; a supervisor can provide such reassurances through the supervision process. The supervisor/supervisee relationship first needs to be established and a sense of trust created, ensuring that both parties remain respectful of each other’s developmental stage, culture, and diversity.

Becoming competent in the role of a CYC is usually a gradual, experiential process that requires ongoing guidance and direction from a supervisor. Due to the intense nature of their role, Child and Youth Care practitioners need regular opportunities to discuss, process, and explore their experiences with a supervisor. A lack of adequate supervision can negatively impact the well-being of both practitioners and young people; this is an ethical issue for CYCs (Mann-Feder, 2018).

One of the challenges for Child and Youth Care practitioners in the supervision process is being able to safely discuss and explore thoughts, feelings, and experiences. For example, expressing their own difficulty dealing with young people or discussing their own biases. Practitioners need a safe space to reflect on their own racism, homophobia, or related issues. This type of critical reflection can be challenging, and these issues often remain unexplored because of the taboo associated with them (Gharabaghi, 2008). Feeling safe to work through these things with your supervisor is imperative.

When supervision occurs, it can be therapeutic in nature, but “however therapeutic the experience may be, maintaining a focus on career-oriented growth and development should be a theme of the process” (Hilton, 2005, para. 7). Supervision is also a reciprocal process where the supervisor can teach the student and the student can teach the supervisor: “In much the same way as good child and youth care work, good supervision is an interactive and artistic process and when skillfully done, it enhances the effectiveness and continued development of child and youth care workers who in turn do better work with children and youth” (Burnison, 2007, para 16).

Think About It

Review the following scenario and respond to the questions that follow:

A new CYCP grad is very excited about being hired for her first full-time position at a residential centre. On her third day, an eight-year-old child screams, “I hate you! You are fat and ugly!” at her. The CYCP feels hurt and notices that she is reactive toward the child. The CYCP’s supervisor observed this interaction and checks in with her at the end of the shift. The CYCP first states that she is fine and not upset about the interaction, but after a few minutes she admits she felt that the child had been rude and not respectful to her (adapted from Fraser & Ventrella, 2019).

This image is for illustration purposes only. The individual pictured is not represented in the case study.

This image is for illustration purposes only. The individual pictured is not represented in the case study.

This module introduced you to professionalism in the context of the Child and Youth Care practitioner’s comportment and choices. Together, when we all practice professionalism, and respect the boundaries of those around us, we contribute to a respectful workplace for our colleagues and our clients. You were also introduced to the basics of ethics as they pertain to the CYC profession. You navigated several case studies where you applied the ethics you were learning about. Finally, you learned about the importance of supervision in the area of Child and Youth Care.

Additional Resources

Child and Youth Care Certification Board (CYCCB). (2016). Competencies. College Station, TX.

Curry, D., Eckles, F., Stuart, C., & Qaqish, B. (2010). National child and youth care practitioner professional certification: Promoting competent care for children and youth. Child Welfare, 89(2), 57–77.

Online Self-Check

Conclude this module by completing the following module self-check quiz:

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/introtoplacement/?p=134#h5p-2

Bring to Class

Now, go to the following link and select one ethical dilemma that resonates with you. Bring your selected dilemma to our next class and be prepared to discuss it with your peers.

Burnison, M. (2007). Supervision: It’s what you do. CYC-Online, (97). Retrieved from https://cyc-net.org/cyc-online/cycol-0207-burnison.html

Charles, G., & Garfat, T. (2016). Chapter 2: Supervision – A matter of mattering. In Supervision in child and youth care practice (pp. 22–28). The CYC-Net Press.

Child and Youth Care Certification Board. (2010). Competencies for professional Child & Youth Work Practitioners. Association for Child and Youth Care Practice. Retrieved from https://cyccb.org/images/pdfs/2010_Competencies_for_Professional_CYW_Practitioners.pdf

Child and Youth Care Certification Board. (2016). How certification makes a difference. Author. Retrieved from https://www.cyccb.org/

Child and Youth Care Certification Board. (2017). Standards of practice of North American child and youth care professionals. Association for Child and Youth Care Practice.

College of Registered Nurses of Manitoba (2019). Professional boundaries for therapeutic relationships. Retrieved from https://www.crnm.mb.ca/uploads/document/document_file_99.pdf?t=1550609946

Davidson, J. C. (2004). Where do we draw the lines? Professional relationship boundaries and child and youth care practitioners. Journal of Child and Youth Care Work, 19, 31–42.

Fox, L. (2019). Compassionate caring: Using our heads and hearts in work with troubled children and youth. The CYC-Net Press.

Fraser, T., & Ventrella, M. (2019). Supervision: Integrating competencies. In A tapestry of relational child and youth care competencies (pp. 219–239). Canadian Scholars.

Garfat, T. (2008). The inter-personal in-between: An exploration of relational child and youth care practice. In G. Bellefeuille & F. Ricks (Eds.), Standing on the precipice: Inquiry into the creative potential of Child and Youth Care practice. MacEwan Press.

Gharabaghi, K. (2008). Values and ethics in child and youth care practice. Child & Youth Services, 30(3–4), 185–209.

Hilton, E. (2005). Understanding supervision. CYC-Online, 73, CYC-Net Press. Retrieved from https://cyc-net.org/cyc-online/cycol-0205-hilton.html

Lam, R., & Cipparrone, B. (2008, February). Achieving cultural competence – ministry of children … Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services. Retrieved November 1, 2021, from http://www.children.gov.on.ca/htdocs/English/documents/specialneeds/residential/achieving_cultural_competence.pdf

Mann-Feder, V. R. (2021). Doing ethics in child and youth care: A North American reader. Canadian Scholars.

Ontario Association of Child and Youth Care. (2019). About the OACYC. Retrieved from https://oacyc.org/about/

Oxford Learner’s Dictionaries. (n.d.). Boundary. In oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com dictionary. Retrieved January 3, 2022, from https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/definition/american_english/boundary

Ricks, F. (1994). Ethical dilemmas in child and youth care practice: Our code of ethics reflects our cultural values. Child Care Worker, 12(10), 8.

Smiar, N. (July 2, 2019). What should I do? Professional ethics in child and youth care work [Paper presentation]. NACCW 22nd Biennial Conference and CYC-Net 4th World Conference, Durban, South Africa.

Stuart, C., & Fryer, K. (2021). Foundations of child and youth care (3rd ed.). Kendall Hunt.

University of Kansas Center for Community Health and Development. (n.d.). Choosing and adapting community interventions: Ethical issues in community interventions. Community Tool Box. Retrieved from https://ctb.ku.edu/en/table-of-contents/analyze/choose-and-adapt-community-interventions/ethical-issues/main

Winfield, J. (2003). Taking care of our professional code of ethics. Child & Youth Care, 21 (10), 23.

II

We each have an identity comprising various aspects that are important to who we are and how we relate to the world. It is important to recognize that our identities are not fixed and we are constantly being shaped and reshaped by what goes on around us. Being aware of the many identities that make up our multicultural selves is important, as we can then begin to understand how these aspects of ourselves shape the way we view the world.

Your Turn

Complete the following exercise to identify some of the aspects of yourself that are important in defining who you are. Click the link below to open the exercise in a new window:

The Child and Youth Care Certification Board (CYCCB, 2010) identifies that professional CYC practitioners should actively promote respect for cultural and human diversity as a core competency. They emphasize that the professional practitioner should seek self-understanding and be able to access and evaluate information related to cultural and human diversity; this knowledge should then be integrated into developing respectful and effective child and youth care practice (CYCCB, 2010).

Cultural and human diversity are integral to all our relationships with children, youth, and families. As a CYC student, you will have many more opportunities throughout your program to explore and learn about cultural and human diversity; the purpose of this module is to introduce you to this topic and help you begin to explore where you are in this regard and how it might influence you while on your placements.

“Education is the key to learning things we are unfamiliar with. To be an effective support to children/youth and families, it is important to understand our differences and similarities. Do not ignore or be afraid of those differences. When you encounter people from another culture, striving for cross-cultural understanding will strengthen your ability to provide support.” Shelly Nelson-Bond, Sault College CYC Program Faculty

When we begin thinking about what human diversity means, it helps to start with the basics. According to Fraser and Ventrella (2019), there are nine major factors that set groups apart from one another and give individuals and groups elements of identity, including:

We could consider expanding this list to include identity markers like sexual orientation and disability.

Diversity refers to blending groups of different identities to give rise to different perspectives born out of various experiences. When diversity is valued, individual differences are respected and celebrated. Individuals should never feel they need to hide or erase parts of their identity. We’ll talk more about diversity below.

Culture consists of the shared beliefs, values, and assumptions of a group of people who learn from one another and teach to others that their behaviours, attitudes, and perspectives are the correct ways to think, act, and feel. It is helpful to think about culture in the following five ways:

The iceberg (shown in the figure below) is a commonly used metaphor to describe culture because it illustrates the tangible and the intangible aspects of culture. When talking about culture, most people focus on the visible “tip of the iceberg,” which makes up just 10 percent of the object. The rest of the iceberg, 90 percent of it, is below the waterline and not readily visible to us.

Many people, when they find themselves in intercultural situations, pick up on the cultural differences they can see—things on the “tip of the iceberg.” Things like food, clothing, and language difference are easily and immediately obvious, but focusing only on these can mean missing or overlooking deeper cultural aspects such as thought patterns, values, and beliefs. It is imperative that CYC practitioners recognize how culture is much deeper than things that can been seen, and are open to learning about the elements below the surface as well.

More than just the clothes we wear, the movies we watch, or the video games we play, all representations of our environment are part of our culture. Culture also involves the psychological aspects and behaviours that are expected of members of a specific group. From the choice of words (message), to how we communicate (e.g., in person or by e-mail), to how we acknowledge understanding with a nod or a glance (non-verbal feedback), to internal and external interference, all aspects of communication are influenced by culture.

The Canadian Centre for Diversity and Inclusion (2022) defines cultural competence as an “awareness and understanding of different cultures and practices, and the ability to accept and bridge differences between cultures for effective communication” (p. 8). The key here is that you are open to learning about other cultures and practices and that you respect how everyone views the world through a lens influenced by the different aspects of their identity. Sandy Macdonald, former Sault College Child and Youth Care program coordinator and faculty member, shares the following regarding cultural competence:

Cultural competence is more than simply being sensitive to cultural differences. It is a professional skill that allows you to work effectively with individuals and families whose cultural values, beliefs, traditions, and worldview may be different from your own. In practice, it means implementing strategies that are respectful of other cultures’ customs, values, and styles of communication. It also means identifying and eliminating barriers, building trust, and honouring the unique perspectives of diverse client populations.

On placement, you can practice cultural competence by showing genuine interest in clients’ cultural backgrounds and traditions, and by demonstrating humility, openness, and a sincere desire to learn. Things as simple as pronouncing clients’ names correctly, and using culturally relevant materials wherever possible, are meaningful gestures of competence and caring. (S. Macdonald, personal communication, November 22, 2021)

In “Video 1: What is Cultural Competence?” by Arkansas Open Educational Resources (OER), University students talk about what cultural competence means to them.

To access a transcript for this video, please click Watch on YouTube.

Cultural humility has been offered as an alternative to the expression cultural competence, which was used to acknowledge the importance of culture and adapting services to meet culturally-unique needs. Because cultural competence was often seen as limited and even problematic, cultural humility is increasingly being adopted within field settings, both in health and social services. Cultural humility can be described as the cultivation of self-awareness, while acknowledging the “cultural values and structural forces” that affect service user experience and opportunities (Fisher-Bone et al., 2014, p. 172). For Fisher-Bone et al. (2014), taking into account structural disparities and the intricacy of culture “strengthens our social justice commitment as social work practitioners” (p. 172).

Power is unequally distributed globally and in society; some individuals or groups wield greater power than others, thereby allowing them greater access and control over resources. Wealth, racism, citizenship, patriarchy, heteronormativity, and education are a few key social mechanisms through which power operates. Although power is often conceptualized as power over other individuals or groups, other variations are power with (used in the context of building collective strength) and power within (which references an individual’s internal strength). Learning to “see” and understand relations of power is vital to organizing progressive social change.

Privilege can be defined as a group of unearned cultural, legal, social, and institutional rights extended to a group based on their social group membership. Individuals with privilege are considered to be the normative group, leaving those without access to this privilege to be seen as invisible, unnatural, deviant, or just plain wrong. Most of the time, these privileges are automatic, and most individuals in the privileged group are unaware of them. Some people who can “pass” as members of the privileged group might have access to some levels of privilege.

Watch “Privilege is power. How you can use it to do some good!” by CBC. While you watch, reflect on the ways you have privilege. How can you use this privilege to help others?

To access a transcript for this video, please click Watch on YouTube.

Social identities are group identities. Beyond personal identities, we understand ourselves, and others recognize us, as belonging to social groups. Membership in social identity groups (e.g., religion, ethnicity, gender) are shaped in shared histories and experiences. They are further influenced by external forces such as legal decisions and historical factors and day-to-day interactions. Social identities are an important intersectional component of personal identities.

Personal identities are individual traits that make up who you are, including your hobbies, interests, experiences, and personal choices. Many personal identities are things that you get to choose and that you can shape for yourself.

In broad terms, diversity is any dimension that can be used to differentiate groups and people from one another. It involves respect for and appreciation of differences in ethnicity, gender, age, national origin, ability, sexual orientation, faith, socio-economic status, and class. But it’s more than this. It includes differences in life experiences, learning and working styles, and personality types that can be engaged to achieve excellence in teaching, learning, research, scholarship, and administrative and support services.

Inclusion is the active, intentional, and ongoing engagement with diversity, where each person is valued and provided with the opportunity to participate fully in creating a successful and thriving community. It also means creating value from the distinctive skills, experiences, and perspectives of all members of our community, allowing us to leverage talent and foster both individual and organizational excellence.

Bias is a prejudice. It is an inclination or preference towards someone/something, especially one that interferes with impartial judgement.

Oppression is the systemic and pervasive nature of social inequality woven throughout social institutions as well as embedded within individual consciousness. Oppression fuses institutional and systemic discrimination, personal bias, bigotry, and social prejudice in a complex web of relationships and structures that saturate most aspects of life in our society.

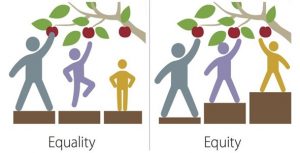

Equity is the guarantee of fair treatment, access, opportunity, and advancement for all. It requires the identification and elimination of barriers that prevent the full participation of some groups. This principle acknowledges that there are historically under-served and underrepresented populations in the social areas of employment, the provision of goods and services, as well as living accommodations. Redressing unbalanced conditions is needed to achieve equality of opportunity for all groups. Equity is not the same as equality.

Equality means each individual or group of people is given the same resources or opportunities, while equity recognizes that each person has different circumstances and allocates the exact resources and opportunities needed to reach an equal outcome.

This chapter contains material taken from “Power, Privilege & Bias – Overview” by Queens University, licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.

This chapter contains adapted material from Introduction to Professional Communications – Simple Book Publishing (pressbooks.pub) by Melissa Ashmun, used under a Creative Commons-Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license.

The three professional competencies identified by the Child and Youth Care Certification Board (CYCCB, 2016) under the Cultural and Human Diversity domain of child and youth care practice are introduced below. In each of these areas, you will gain a general understanding of what you will be working towards through your education and practicum experiences.

Delano (2004) reminds us that “the key to delivering culturally competent services to children and families we care for lies in accepting that being diverse is not enough, and that we never really can become fully culturally competent” (para. 1). A practitioner needs to remain open to the idea that cultural competency is an ongoing process and requires that CYC professionals “should constantly be moving forward by learning about others and accepting how our potential biases and strong core values might affect our ability to be culturally competent” (Delano, 2004, para. 1). In this domain, the emphasis is on the CYC professional’s ability to reflect on their own level of cultural understanding, assess their own biases, and support children, youth, families and programs in “developing cultural competence and appreciation of human diversity” (CYCCB, 2016, p. 13).

“As you enter placement, remember that it is normal to feel anxious about this new experience. Being aware of your ‘blind spots’ or biases will be so important. It’s a sign of strength to admit what we don’t know and allows us to grow and expand in our understanding of ourselves and others. Enjoy the process of learning more about you.” Donna Mansfield, Sault College CYC Program Faculty and College Placement Supervisor

Please click the following heading to view a list of competencies in this area:

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/introtoplacement/?p=83#h5p-10

Try It Out

Project Implicit is a non-profit organization and international, collaborative network of researchers who investigate implicit social thinking, or thoughts and feelings largely outside of conscious awareness and control. Complete the following tasks:

The next area of the Cultural and Human Diversity competency domain focuses on the relationships that CYC professionals have in their work and on communication that is sensitive to cultural and human diversity. Culture—which may include language, values, beliefs, and behaviours—can and will shape the interactions between a CYC practitioner and those they work with. A CYC worker must be aware of a child, youth, and/or family’s culture to ensure that relationships and communication within those relationships are sensitive to all involved.

Please click the following heading to view a list of competencies in this area:

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/introtoplacement/?p=83#h5p-11

It’s Your Turn

The way in which we communicate can differ considerably from culture to culture. This activity identifies some important areas in which paralinguistic tendencies (volume, speed of speech, and so on), extra-linguistic practices (gestures, eye contact, touch, physical proximity, and so on) and communication styles (direct versus indirect, and so on) differ across national boundaries. Open the Exploring Cultural Communication Approaches (.docx) document now and download the file to your computer. Then, follow the instructions in the file to complete the exercise.

This area of the Cultural and Human Diversity domain of child and youth care practice, as identified by the CYCCB, is focused on developmental practice methods that are sensitive to cultural and human diversity. This sensitivity to cultural and human diversity should be present when designing and implementing programs; group work; and counselling and behavioural guidance for children, youth, and families; as well as in setting boundaries and limits on behaviour.

Please click the following heading to view a list of competencies in this area:

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/introtoplacement/?p=83#h5p-12

Try It Out

“To heal a nation, we must first heal the individuals, the families and the communities.” – Art Solomon, an Anishinaabe elder

Indigenous colonization can be described as the action or process of settling among and establishing control over the Indigenous People of an area. As the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (2019) notes, “Canada is a settler colonial country. European nations, followed by the new government of ‘Canada,’ imposed its own laws, institutions, and cultures on Indigenous Peoples while occupying their lands. Racist colonial attitudes justified Canada’s policies of assimilation, which sought to eliminate First Nations, Inuit, and Métis Peoples as distinct Peoples and communities” (National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, 2019, p. 4).

According to the Best Start Resource Centre (2012), “Prior to colonization, sacred teachings were ways of life, passed along orally and through lived experience” (p. 7). Elders in Indigenous communities taught people about their place and relationship to the universe and each other: “Indigenous knowledges are conveyed formally and informally among kin groups and communities through social encounters, oral traditions, ritual practices, and other activities” (Bruchac, 2014, p. 1). This traditional knowledge, which “can be defined as a network of knowledges, beliefs, and traditions intended to preserve, communicate, and contextualize Indigenous relationships,” has been placed under continuous threat because of colonization (Bruchac, 2014, p. 2).

For more than 150 years, Indigenous children were taken from their families and communities to attend residential schools, often located very far from their homes. According to the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation (n.d.), “more than 150,000 children attended Indian Residential schools. Many never returned” (para. 1). The negative effects of residential schools were passed from generation to generation. Indigenous Peoples have been working hard to overcome the legacy of residential schools and to change the realities for themselves, their families, and their Nations. By ending the silences under which Indigenous Peoples have suffered for many decades, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission opened the possibility that we may all come to see each other and our different histories more clearly and work together in a better way to resolve issues that have long divided us. It is the beginning of a new kind of hope rooted in the belief that telling the truth about our common history gives us a much better starting point in building a better future (Wilson, 2018).

In the video “Colonization” by Werklund School of Education (2018), Indigenous knowledge keepers Reg Crowshoe and Kerrie Moore share their wisdom and experiences about the impacts of colonization, including residential schools, on Indigenous Peoples:

To access a transcript for this video, please click Watch on YouTube.

Whether you come from the perspective of an Indigenous or non-Indigenous person, it is important to understand the impacts of colonial history. For the Indigenous person, learning about colonial history creates feelings of hurt, anger, and possibly shame. For the non-Indigenous person, learning about this history can lead to feelings of remorse and guilt. Some people, whether Indigenous or not, might say that colonization was a thing of the past and prefer to forget about this colonial history. The Calls to Action from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission recommend that Canadians move towards reconciliation of this colonial history. This reconciliation involves learning about colonial history—the true history, not the history that has been presented in history books. It is about re-writing the history from an Indigenous perspective. It is about creating a new beginning in Indigenous/non-Indigenous relations and “re-storying” that colonial history as a step towards reconciliation (Manitowabi, n.d.).

A history of colonization exists and persists all around us. This history is not your fault, but it is absolutely your responsibility. In the TEDx Talk, “Decolonization is for Everyone,” Nikki Sanchez (2019) discusses what colonization looks like and how it can be addressed by everyday people through decolonization. An equitable and just future depends on the courage we show today. After you finish watching the video, try to formulate one action that you can take in your life today to work towards decolonization.

To access a transcript for this video, please click Watch on YouTube.

The impacts of colonial history on Indigenous peoples in Canada have been significant. Strategic attempts to assimilate Indigenous peoples through colonial policies have resulted in many losses, including land and strong connections with Indigenous People’s language, culture, and traditional ways of knowing and being. The impact of these policies is evident through inter-generational traumas experienced by Indigenous Peoples across Canada. To engage in reconciliation, we must understand how colonization has impacted these communities’ traditions, their institutions, and their practices (Cull et al., 2018).

According to Benton-Banai, as cited in Manitowabi (n.d.), the Seven Grandfather Teachings “form the foundation of an Indigenous way of life” and are the basis of sharing and respect (para. 1). Several versions of the Seven Grandfather Teachings exist; this abbreviation of Benton-Banai’s version is by Susan Manitowabi (n.d.):

The Creator gave the seven grandfathers the responsibility to watch over the people. In this recounting of the story, the seven grandfathers, seeing that the people were living a hard life, sent a messenger down to the earth to find someone who could tell what Ojibway life should be and bring him back. The messenger searched all directions—North, South, West and East—but could not find anyone. Finally, on the seventh try, the messenger found a baby and brought him back to where the grandfathers were sitting in a circle. The grandfathers, happy with the messenger’s choice, instructed him to take him all around the earth so the baby could learn how the Ojibway should lead their lives. They were gone for seven years. Upon his return, as a young man, the grandfathers, recognizing the boy’s honesty, gave him seven teachings that he could take with him. They are as follows: . . .

Nibwaakaawin—Wisdom: Wisdom, a gift from the Creator, is to be used for the good of the people. The term “wisdom” can also be interpreted to mean “prudence” or “intelligence.” This means that we must use good judgement or common sense when dealing with important matters. We need to consider how our actions will affect the next seven generations. Wisdom is sometimes equated with intelligence. Intelligence develops over time. We seek out the guidance of our Elders because we perceive them to be intelligent; in other words, they have the ability to draw on their knowledge and life skills in order to provide guidance.

Zaagi’idiwin—Love: Love is one of the greatest teachers. It is one of the hardest teachings to demonstrate, especially if we are hurt. Benton-Banai (1988) states . . . , “To know Love is to know peace.” Being able to demonstrate love means that we must first love ourselves before we can show love to someone else. Love is unconditional; it must be given freely. Those who are able to demonstrate love in this way are at peace with themselves. When we give love freely it comes back to us. In this way love is mutual and reciprocal.

Minaadendamowin—Respect: One of the teachings around respect is that in order to have respect from someone or something, we must get to know that other entity at a deeper level. When we meet someone for the first time, we form an impression of them. That first impression is not based on respect. Respect develops when one takes the time to establish a deeper relationship with the other. This concept of respect extends to all of creation. Again, like love, respect is mutual and reciprocal—in order to receive respect, one must give respect.

Aakode’ewin—Bravery: Benton-Banai (1988) states that “Bravery is to face the foe with integrity.” This simply means that we need to be brave in order to do the right thing, even if the consequences are unpleasant. It is easy to turn a blind eye when we see something that is not right. It is harder to speak up and address concerns for fear of being retaliated against. Oftentimes, one does not want to “rock the boat.” It takes moral courage to be able to stand up for those things that are not right.

Gwayakwaadiziwin—Honesty: It takes bravery to be honest in our words and actions. One needs to be honest first and foremost with oneself. Practicing honesty with oneself makes it easier to be honest with others.

Dabaadendiziwin—Humility: As Indigenous people we understand our relationship to all of creation. Humility is to know your place within Creation and to know that all forms of life are equally important. We need to show compassion (care and concern) for all of creation.

Debwewin—Truth: “Truth is to know all of these things” (Benton-Banai, 1988). All of these teachings go hand in hand. For example, to have wisdom, one must demonstrate love, respect, bravery, honesty, humility and truth. You are not being honest with yourself if you use only one or two of these teachings. Leaving out even one of these teachings means that one is not embracing the teachings. We must always speak from a truthful place. It is important not to deceive yourself or others.

Just as the boy was instructed to learn these teachings and to share them with all the people, we also need to share these teachings and demonstrate how to live that good, healthy life by following the seven grandfather teachings.

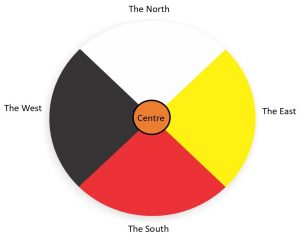

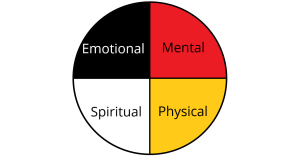

There are many versions of medicine wheel teachings and they vary from community to community, but there are some foundational concepts that are common to most. Hart and Nabigon describe the medicine wheel as an ancient symbol conceptualized as a circle divided into four quadrants/directions; each of these quadrants contains teachings about how we should live our lives, and about the need to balance all four aspects of the being—mental, emotional, physical, and spiritual (as cited in Manitowabi, n.d.). The medicine wheel reminds us that everything comes in fours: the four seasons, the four stages of life, the four races of humanity, four cardinal directions, etc.

The following is an synopsis of the medicine wheel teachings provided by Lillian Pitawanakwat-Ba from Whitefish River First Nation (as cited in Manitowabi, n.d.):

The Center: Represents the fire within and our responsibility for maintaining that fire. Pitawanakwat recalls that as a child, her father would ask at the end of the day, “My daughter, how is your fire burning?” In recalling the events of the day, she would reflect on whether she had been offensive to anyone, or whether or not she had been offended. This was an important part of nurturing the fire within as children were taught to let go of any distractions of the day and make peace within ourselves in order to nurture and maintain that inner fire. It is also a reminder that you need to maintain balance in all areas.

The East (Waabinong): According to Pitawanakwat, the springtime, and the spring of life are represented in the east. All life begins in the east; we begin our human life as we journey from the spirit world into this physical world. The teachings from the east remind us that all life is spirit (the wind, earth, fire, and water—all those things that are alive with energy and movement) and that to honour that life, we offer tobacco in thanksgiving. Prayers of thanksgiving honour all those things that we cannot exist without, for the breath of life, the cycles of time and to be grateful for life [sic]. We are especially grateful for natural law. All our teachings come from the natural world around us.

The South (Zhawanong): The summer and youth are represented in the southern direction. Summer is a time of continued nurturance. Youth are at a stage in life where they are no longer children and are not quite adults. They may be searching for what they had to leave behind in their childhood and struggling with their identity. In this direction, we are reminded to look after our spirits by finding that balance within ourselves and to pay attention to what our spirit is telling us. If we listen to our intuition, then the spirit will help to keep us safe. Youth who grow up without spirit nurturance have no direction and are at risk of being exposed to all kinds of dangers and distractions; their spirits have not been nurtured. Youth need nurturance, guidance and protection to help them through this transitional phase of their lives.

The West (Epangishmok): The western direction represents the adult stage of life. Death is also represented in this direction. Death comes in many forms – the end of our physical journey and crossing back into the spirit world; the setting sun and end of the day; or recognition that as old thoughts and feelings die, new ones emerge. The heart is also represented in the west. The heart helps us to evaluate, appreciate and enjoy our lives. By nurturing our hearts, we create balance in our lives.

The North (Kiiwedinong): The teachings of the north remind us to slow down and rest. The north is referred to as the rest period, a time to be respectful of the need to care for and nurture the physical body. It is also referred to by some as a period of remembrance—a time for contemplation of what has happened in life. Winter is represented in the north—it is a time for rest for the earth. It is also a time of reflection—on being a child, a youth and an adult. Elders, pipe carriers and the lodge keepers, reside in the north. Their teachings help us to embrace all aspects of our beings so that we can feel and experience the fullness of life. Wisdom also resides in the north. Elder’s share their stories in the winter months.

On your journey of decolonization and Indigenization, it is helpful to self-assess your own intentions and behaviours in your present position as a post-secondary student. The Indigenized integral professional competency self-assessment is a tool you can use to identify your strengths and areas for development in working with Indigenous students and communities.

The Indigenized Integral Professional Competency Framework was developed using the Indigenized integral model (intention, community, behaviour and systems fit) to provide staff with tools to assess their levels of competency working with Indigenous communities. This model provides an opportunity to measure a level of baseline professional competency and skills as well as to self-reflect on your current knowledge and create a learning plan to deepen your understanding and change practice to be more holistic and balanced.

The Indigenized Integral Professional Competency Framework measures three areas of professional competencies for working with Indigenous Peoples and community partners:

Each quadrant of the Indigenized Integral Model framework is aligned with animal traits from coastal Indigenous knowledge. Tap on the question mark icon for each of the animals below to learn more:

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/introtoplacement/?p=87#h5p-13

Active Learning

Complete the Indigenized Integral Professional Competency Self-Assessment activity (this link opens on a new page).

Once you have completed the assessment, review your answers for the competencies you rated:

Select two areas that you feel you would like to improve in and write down some ideas of how you might be able to do so. Bring your reflections/responses to class for discussion.

This chapter contains material adapted from Pulling Together: A Guide for Front-Line Staff, Student Services, and Advisors by Ian Cull; Robert L. A. Hancock; Stephanie McKeown; Michelle Pidgeon; and Adrienne Vedan and is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

This chapter contains content adapted from Historical and Contemporary Realities: Movement Towards Reconciliation by Susan Manitowabi is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

This chapter contains content adapted from Pulling Together: Foundations Guide by Kory Wilson is used under a CC BY-NC 4.0 licence.

Watch the following video of university students discussing what it means to become culturally competent. They provide specific strategies anyone can use to advance along the continuum.

To access a transcript for this video, please click Watch on YouTube.

Based on the Intercultural Development Inventory (IDI) framework, three major steps are needed to grow in cultural competence:

A deeper cultural self-understanding helps you to make sense of and respond to differences in cultural perspectives based on your own culturally learned perspectives, while a deeper cultural other-understanding helps you make sense of and respond to differences in culture as they are presented by other cultural groups.

The following are tips for staff and foster parents on becoming culturally competent, outlined by the Ministry of Children and Youth Services, Ontario (as cited in Lam & Cipparone, 2008). As you review them, think about ways you can implement these strategies into your placements and your own life.

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/introtoplacement/?p=413#h5p-8

This chapter contains content from Creating Cultural Competence by Jacquelyn Wiersma-Mosley and Margaret Miller Butcher is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This module introduced you to cultural competence—although some prefer to use the term cultural humility—in the context of the Child and Youth Care practitioner’s behaviour and perspectives. By self-examining your own identity, your privilege, and your implicit biases, you identified some areas where you can work to implement appropriate strategies and resources to instil cultural competence as a life-long learning process. In particular, you took a long look at the harmful legacy of colonization and learned about ways to incorporate Indigenous ways of knowing into your work with children, youth, and families. Remember, when we work to dismantle harmful power structures that only benefit some and remove cultural barriers, we work towards a more diverse and inclusive world for everyone.

The subject matter discussion in this module is complex and far-reaching. It is impossible to explore it thoroughly in the time we have. If you are able to dedicate some more time to investigating the subject matter covered in this module, please start by working through the list of resources below.

Additional Resources

Land Governance: Canada’s colonial history by the David Suzuki Foundation (Apr 22, 2021). [Video]

What is Reconciliation? by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada ( Mar 30, 2015). [Video]

Tatum, B. D. (2000). The complexity of identity: “Who am I?.” In Adams, M., Blumenfeld, W. J., Hackman, H. W., Zuniga, X., Peters, M. L. (Eds.), Readings for diversity and social justice: An anthology on racism, sexism, anti-semitism, heterosexism, classism and ableism (pp. 9-14). New York: Routledge.

Indigenous Tourism BC. (n.d.) Considerations When Working with Indigenous Communities.

Canadian Centre for Diversity and Inclusion. (2020). A brief history of race relations in Canada.

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie: The danger of a single story by TED (Oct 7, 2009). [Video].

Wexler, L. & Gone, J. (2012). Culturally responsive suicide prevention in Indigenous communities: Unexamined assumptions and new possibilities. American Journal of Public Health, 102(5), 800-806.

Online Self-Check

Conclude this module by completing the following module self-check quiz:

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/introtoplacement/?p=141#h5p-14

Bruchac, M. (2014). Indigenous knowledge and traditional knowledge. In Smith, C. (Ed.), Encyclopedia of global archaeology, 3814–3824. Springer.

Canadian Centre for Diversity and Inclusion. (2022, January). Glossary of terms: A reference tool. https://ccdi.ca/media/3150/ccdi-glossary-of-terms-eng.pdf

Child and Youth Care Certification Board. (2010). Competencies for professional child & youth work practitioners. Association for Child and Youth Care Practice. https://cyccb.org/images/pdfs/2010_Competencies_for_Professional_CYW_Practitioners.pdf

Cull, I., Hancock, R. L. A., McKeown, S., Pidgeon, M., & Vedan, A. (2018, September 5). Pulling together. A guide for front-line staff, student services, and advisors. BC Campus Open Publishing. https://opentextbc.ca/indigenizationfrontlineworkers/ CC BY-NC 4.0

Delano, F. (2004) Beyond cultural diversity: Moving along the road to delivering culturally competent services to children and families. Journal of Child and Youth Care Work, 19, 26–30.

Fisher-Borne, M., Cain, J. & Martin, S. (2014). From mastery to accountability: Cultural humility as an alternative to cultural competence. Social Work Education, 34(2), 165–181.

Fraser, T. A., & Ventrella, M. (2019). A tapestry of relational child and youth care competencies. Canadian Scholars.

Fulcher, L. C. (2012, January 1). Culturally responsive work with Indigenous children and families. Reclaiming Children and Youth, 21(3), 53–57.

Lavallée, L., & Menzies, P. (2015). Journey to healing: Aboriginal people with addiction and mental health Issues: What health, social service and justice workers need to know. Centre for Addiction & Mental Health.

Manitowabi, S. (n.d.). Historical and contemporary realities: Movement towards reconciliation. eCampus Ontario Open Library. https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/movementtowardsreconciliation/

National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation. (n.d.). Residential school history. NCTR. https://nctr.ca/education/teaching-resources/residential-school-history/

National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls. (2019). Executive summary of the final report: Reclaiming power and place. https://www.mmiwg-ffada.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Executive_Summary.pdf

Pendry, L. F., Driscoll, D. M., & Field, S. C. T. (2007). Diversity training: Putting theory into practice. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 80(1), 27–50. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317906X118397

Wiersma-Mosley, J. & Miller Butcher, M. (2021, August 27). Creating cultural competence. Open Textbooks University of Arkansas Libraries Butcher. https://uark.pressbooks.pub/creatingculturalcompetence/ CC BY 4.0

Wilson, K. (2018). Pulling together: Foundations guide. BCcampus. https://opentextbc.ca/indigenizationfoundations/

III

As this module focuses on the Self and awareness of who you are—important concepts to learn on the journey to becoming an effective child and youth care (CYC) practitioner—your first task is to do some self-exploration. In this reflection exercise, you will complete a survey that will help you identify your character strengths.

Your Turn

Take a few minutes and complete the VIA Character Strengths Survey (this link will open in a new page). You will need to register (it’s free) before doing the survey. This survey will allow you to begin to understand where your strengths are, and where you might need to look at improving. It will also help you reflect on your Self when you are on placement, as you can consider where your top character strengths may have helped or hindered you in that situation.

Once you have completed the survey and have your results, answer the questions on this CYC Self-Reflection Exercise form (this link will open in a new page).

“Self is the vehicle by which relationships develop” (Budd, 2020, p. 80).

What is the Self? And why is it an important component of Child and Youth Care practice? There are many people who have attempted to explain/convey the concept of the Self throughout history, including philosophers, theorists and writers, but for the purposes of this resource, the following definition, written by prominent CYC practitioner Michael Burns, will be used:

The Self is the expression of the union of your mind and your body in relationship to your culture and the environment you occupy. The Self is the sum of all that is you; your experiences, your relationships past and present, your genetics, your mind, and your body—everything about you, conscious and unconscious. (Burns, 2016, p. 9)

So, essentially, the Self is you. Your experiences, your perceptions, your values, your relationships—everything that has happened to you up to this point in your life has impacted how you came to be who you are today. It is difficult to truly know your Self without reflecting on past experiences and how you came to be where you are now. All those experiences will come into play in the relationships you have or will have with children and youth in your placements and during your future career as a CYC.

Knowing your Self is an ongoing and reflective process that will continue throughout your career as a CYC—and one that is necessary to being an effective CYC. But it isn’t an easy task getting to know one’s Self, which is why it is a topic discussed repeatedly in CYC education.

“Reflect, remain gentle and take action. Reflecting on the good and not so good from a gentle approach is in everyone’s favor. If you reflect gently on your – self awareness, self care, professionalism & cultural competency and take action to what needs your attention….you will always be growing and lighting that good way for other’s that need you.” Chantelle Day, CYC Grad and Placement Supervisor

The work we do as CYCs requires that we make connections and build relationships with children, youth, and families within their life space. To do this, CYCs need to rely on what Burns (2016) calls the “heart-brain:” a powerful and significant tool used to connect with children/youth by means of the heart—an emotional, personal, and sensory connection. You cannot develop these connections and work from the heart unless you have a strong and healthy connection to your own Self. When a CYC has this healthy connection to Self, they can then, through relationships, allow the children and youth to connect with their own self-healing powers. To achieve this goal, you, “as a student of child and youth care, must critically self-examine your feelings, thoughts, and behaviours, both past and present, to uncover any major impediment, roadblock, or distorted ideas so that your relationships with children/youth are meaningful and, most of all, authentic” (Burns, 2016, p. 10).

A way to ensure that you are giving children/youth that necessary healthy connection is to “examine who you are and, over time, grow and develop into a CYC with a balanced heart” (Burns, 2016, p. 9). To develop what Michael Burns (2016) calls a balanced heart, you need to “critically explore and reflect on [your] life” and uncover the “ideas, truths, or notions that [you have] formulated as a result of misguided information, emotional disturbance, trauma or faulty cognition” (p. 10). You then need to reflect on how you can “transform them into affirming, inclusive and growth-oriented perspectives” (Burns, 2016, p. 10). This balanced heart takes time and ongoing maintenance to achieve and is not necessarily a straightforward process.

In this module, we will discuss three paths to building and maintaining this balanced heart:

Key Takeaway

Although this module focuses on what you can do to know and care for your Self, don’t forget that sometimes you will need help from others. As you are working through this module, you may be reminded of past traumas or unresolved psychological or emotional issues. If this occurs and you need help processing your experiences, please reach out to a trained professional, such as a licensed counsellor or therapist for support.

“Morally and ethically, it is your responsibility to uncover all the prejudices, biases, barriers, and impediments that may prevent you from assisting children/youth” (Burns, 2016, p. 10).

Child and Youth Care competencies and vocational standards point to the fact that reflective practice is an essential component to our education, training, and practice. As Cragg (2020) notes, “reflective practice facilitates self-awareness and understanding; learning and personal growth; critical thinking; and most importantly, change and improvement to practice” (p. 121).

Reflective practice involves taking an in-depth look at an experience that you were involved in and being able to describe what your specific actions were. You should then be able to analyze and evaluate what occurred so you can learn from that experience and ensure your effectiveness as a CYC. Budd (2020) observes that “reflective learning has been described across the reflective practice literature as a process of reflecting on key issues of concerns that are triggered by experiences and lead to different perspectives” (p. 258). If you are reflecting on your practice, you are learning from your practice.

“It is alright to be unsure of yourself and ask for help when you need it. It is a good idea to have a little notebook or a file, to record insights at the first available opportunity.” Denise Berg, CYC Student Placement Supervisor

Reflective practice enables practitioners to:

Indeed, there are many benefits to reflective practice as a CYC. It allows you to be intentional and thoughtful and to learn from your experiences, which will in turn immensely improve your practice. Through this learning, you can become more self-aware and gain more insight into your clients and the world around you, as well as become more accountable in your actions. Put another way, “When you reflect on practice, you allow yourself the space to consider other ways of thinking and knowing (Bellefeuille & Ricks, 2010) and step outside the paradigm of your position that implicitly conveys power and privilege (Lareau & McNamar Horvat, 1999)” (as cited in Budd, 2020, p. 7). Remember, as a CYC working with youth and children, there is always a power difference. By being mindful of how this power difference benefits you and may disempower the children and youth you work with, and of the important responsibility that comes along with your position of power, you will hold yourself to a higher standard and take responsibility for what you do as a CYC. Therefore, you are less likely to make assumptions and impose harmful narratives on the children and youth you are working with.

For example, you may be working with a young person who presents with challenging behaviours and in the moment you are working with them, you may find it difficult not to react to those behaviours. Your ability to recognize this child’s strengths in that situation might be unintentionally impaired by your own judgements of the child. Utilizing the practice of reflective thinking, you must think about your own experiences and identify how those experiences may be impacting your view of the child. Instead of looking at a situation and thinking, “What is wrong?”, you could shift your thinking to “What is there to be learned here?” to focus on a more strengths-based approach.