Introduction to Market Research

Introduction to Market Research Copyright © by Julie Fossitt is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Introduction to Market Research Copyright © by Julie Fossitt is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

1

2

The intention of the Introduction to Market Research to curate, develop and share the steps to undertake a market research project in a Canadian context. This resource has been developed to be used as a complete course of ten modules or as individual modules, as your context requires. The ten modules are as follows:

Lead: Julie Fossitt

Contributors: Abraham Francis, Paul Carl

Course auditor: Julie Sullivan

Market Research is a core component of any marketer’s tool box, and is included in Ontario-based college curriculum for many diploma and certificate-level courses. The development of this open educational resource is intended to provide anyone – both instructors and students – looking for open tools to learn more about market research in a contemporary Canadian context.

We are actively committed to the accessibility and usability of this textbook. Every attempt has been made to make this OER accessible to all learners and is compatible with assistive and adaptive technologies. We have attempted to accessible learning activities and alternative text.

The web version of this resource has been designed to meet Web Content Accessibility Guidelines 2.0, level AA. In addition, it follows all guidelines in Appendix A: Checklist for Accessibility of the Accessibility Toolkit – 2nd Edition.

If you are having problems accessing this resource, please contact us at jfossitt@sl.on.ca

Please include the following information:

Market research is information that helps marketers understand customers, competitors, and changes in consumer behaviour to help make more informed decisions. The goal of this resource is to help new and emerging marketing students to understand why market research matters and to understand the components of identifying a marketing research problem, designing a research framework, executing the research, and analyzing the data with the ultimate goal to be able to make data-driven decisions. This resource will cover primary and secondary research tools as well as qualitative and quantitative approaches within a Canadian context. Over the course of nine modules, students will learn basic market research skills that will help them design a market research project.

After completing this course, participants should be able to:

This open education resource includes resources copyrighted and openly licensed by multiple individuals and organizations. At the bottom of each chapter, all references are listed for copyright and licensing information specific to the material on that page. If you believe that any information included in this resource violates your copyright, please contact us.

This resource funded by the Government of Ontario. The views expressed in this publication are the views of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the Government of Ontario.

3

Throughout this course, we will use a number of user personas that represent a variety of folks who may live in areas across Canada. These personas are not based on real people, but rather on a snapshot of a few different types of people who might live in our neighbourhoods. User personas are fictional representations (based on real user research) of different types of users that help understand their needs, behaviours, and motivations. User personas originated in the field of user-centred design and were popularized by Alan Cooper in the 1980s as a method of guiding software development. This course will make use of a number of user personas that represent a variety of folks who may live in areas across Canada.

Here are the fictional personas that will bring some of the concepts of market research to life thought this resource:

Background: Isabella, 49, lives on a farm in rural Saskatchewan. She inherited the farm from her parents and is passionate about sustaining her family’s legacy. Isabella manages a small-scale organic produce business alongside her husband. She’s motivated to learn more about marketing to expand their reach beyond local farmer’s markets.

Education: Isabella attended a community college and graduated with an Agriculture diploma.

Social values: Isabella is passionate about her small, rural community and supports sustainable living and local food.

Hobbies and Interests: Isabella doesn’t have a lot of free time due to her work schedule as a farmer, but is passionate about 4-H and teaching young people about farming, gardening, food preparation and food sovereignty.

Marketing Goals: Isabella’s goals are to expand some of her organic honey and prepared preserves beyond farmer’s markets sales.

Challenges: Limited access to high-speed internet for online learning, understanding urban consumer behaviours, and competition with larger commercial farms.

Background: Daniel, 30, resides in a suburban neighbourhood near Toronto. He works as a marketing coordinator for a mid-sized tech company. He’s keen on enhancing his market research skills to identify emerging consumer trends and refine their company’s product positioning.

Education: Daniel has a bachelor’s degree in commerce from an Ontario university. He is considering pursuing an MBA in the future.

Social values: Daniel is very close to his family, who live in a small town outside of Toronto. He wants to ensure that he can help provide support for his grandparents and parents as they age and he isn’t interested in having children of his own. Daniel is still in touch with friends from grade school, although most of them still reside in the small town where he grew up.

Hobbies and Interests: Daniel loves to listen to marketing podcasts, and likes to save up for summer vacations throughout Canada. Daniel is interested in participating in marketing or tech-related professional groups, forums, or associations to network, exchange ideas, and gain insights from industry peers.

Marketing Goals: Improve consumer segmentation strategies, utilize data analytics for better decision-making, and understand the impact of socio-economic factors on consumer behaviour.

Challenges: Balancing work commitments with studies, navigating complex data analysis tools, and applying market research findings within the tech industry.

Background: Maya, 28, lives in downtown Vancouver and works as a freelance graphic designer from her home office. Maya is a single mother with a small child and they rent the top floor of a home. She’s eager to delve into market research to broaden her skill set, seeking to offer comprehensive branding services to her clients.

Education: Maya has a college diploma in graphic design.

Social Values: Maya is a first generation Canadian, with parents from another country. Maya is passionate about teaching her children about cultural traditions that are important to her and her parents, who have since passed away.

Hobbies and Interests: Maya doesn’t have much time for hobbies, as she spends most of her free time running errands and taking her small child to swimming lessons or playdates. Maya enjoys yoga but does it at home using an app, as she isn’t able to get away from her house except on brief breaks during the day when her daughter is at preschool.

Marketing Goals: Learn how market research can enhance design choices, understand client target audiences better, and offer data-driven design solutions.

Challenges: Juggling multiple freelance projects, finding time for additional learning, and applying market research findings effectively in design projects.

Background: Alex, 54, is an entrepreneur in Montreal who owns a small chain of artisanal coffee shops. Alex grew up in western Canada, but moved to Montreal several years ago. Alex speaks English as a first language, but also speaks French fluently. Alex lives with their partner in a condo in downtown Montreal.

Education: Alex has a Master’s Degree in English, and doesn’t have any formal training in business or entrepreneurship. Alex worked at a coffee shop for many years and used that experience to create a chain of coffee shops that specialize in free trade coffee and vegetarian food.

Social Values: Alex is passionate about food and sustainable living, and they work toward building a business that pays a living wage and has a minimal impact on the environment.

Hobbies and Interests: Alex is an avid cyclist and enjoys active vacations with their partner and friends. Alex volunteers for a local climate action organization as a member of their board of directors.

Marketing Goals: Understand customer preferences in the coffee industry, identify opportunities for expansion or diversification, and fine-tune marketing strategies.

Challenges: Limited resources for hiring specialized market research professionals, interpreting market trends accurately, and implementing findings on a small budget.

Background: Daraja, 22, is a university student living in Calgary. She’s pursuing a degree in business administration and aims to specialize in marketing. Her interest in market research stems from a desire to understand consumer behaviour and its impact on business decisions.

Education: Daraja has a high school diploma from another country and moved to Calgary to pursue her Bachelor’s degree. She is in her third year of school.

Social Values: Daraja is passionate about being the first person in her family to be in Canada and to be able to pursue a university degree.

Hobbies and Interests: Daraja works part-time to help with expenses, so doesn’t have a lot of time to pursue hobbies and extra-curricular activities, but she enjoys cooking and making art when time allows.

Marketing Goals: Gain foundational knowledge in market research methodologies, apply theoretical concepts to real-world scenarios, and prepare for a career in marketing research or consultancy.

Challenges: Balancing coursework with additional learning, applying theoretical knowledge practically, and gaining industry exposure while studying.

Singleton, M. (n.d.). User Personas. OERTX. https://oertx.highered.texas.gov/courseware/lesson/4914/overview

I

Learning Objectives

In Module 1, students will learn how to:

The word research refers to the process of looking for answers to problems. In the context of marketing, these problems are typically related to changes in consumer and competitor behaviour. These changes can be caused by trends, such as Tiktok, unplanned global changes like the COVID-19 pandemic or climate change, or planned changes, such as the release of a new iPhone. Market research often focuses on consumer needs and preferences, including what consumers buy and how much they are willing to pay for goods and services, as well as identifying the advantages and disadvantages of competitors.

This is important because businesses and organizations across a wide range of industries need to know who they are reaching—and sometimes even more crucially, who they are not reaching.

The following are some reasons why market research should be considered:

If marketers are able to understand customers and the greater business context, they will be able to market more effectively, meet their needs better, and drive more positive sentiment around their brand. All of this adds up to happier customers and, ultimately, a healthier bottom line.

Ethics is the branch of philosophy that is concerned with morality—what it means to behave morally and how people can achieve that goal. It can also refer to a set of principles and practices that provide moral guidance in a particular field. There are a variety of ethical standards in business, medicine, teaching, and market research. Many kinds of ethical issues can arise in research, especially when it involves human participants.

Here is a video that explains the difference between ethics and law, and introduces the concept of ethics in research.

In Canada, there is a best practice for ethics in research created by the Government of Canada, called the Panel for Research Ethics. This panel develops, interprets and implements the Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans, known as the TCPS 2.

The guidelines in the TCPS 2 are based on the following three core principles:

Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans

Brown University. (2022). Research Ethics. Retrieved January 2, 2024, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mtLPd2u4DiA

Chiang, I.-C. A., Jhangiani, R. S., & Price, P. C. (2015, October 13). Research methods in psychology – 2nd Canadian edition. Research Methods in Psychology 2nd Canadian Edition. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Government of Canada. (2023, January 11). Tri-council policy statement: Ethical conduct for research involving humans – TCPS 2 (2022). Government of Canada, Interagency Advisory Panel on Research Ethics.

Privacy is a concern when it comes to marketing research data. For researchers, privacy is maintaining the data of research participants discretely and holding confidentiality. Many participants are hesitant to provide identifying information for fear of it leaking, being linked back to them personally, or being used to steal their identity. To help respondents overcome these concerns, researchers must identify the research as being either confidential or anonymous.

Confidential data is when respondents share their identifying information with the researcher, but the researcher does not share it beyond that point. In this case, the research may require an identifier to match previous data with the new content—for example, a customer number or membership number. Anonymous data is when a respondent does not provide identifying information at all, so there is no chance of being identified. Researchers should always be careful with personal information, keeping it behind a firewall, behind a password-protected screen, or physically locked away.

One of the most important ethical considerations for marketing researchers is the concept of confidentiality of respondents’ information must be considered. In order to have a rich data set of information, very personal information may be gathered. When a researcher uses that information in an unethical manner, it is a breach of confidentiality. Many research studies start with a statement of how the respondent’s information will be used and how the researcher will maintain confidentiality. Companies may sell personal information, share contact information of the respondents, or tie specific answers to a respondent. These are all breaches of the confidentiality that researchers are held accountable for.

As market researchers, we must prioritize the safety and well-being of human participants, as well as the information gathered throughout the research process, at all times. Using ethical guidelines and protecting respondents’ information is a core component of market research.

Insights Association Code of Standards

The Insights Association’s Code of Standards and Ethics for Market Research and Data Analytics is reviewed annually by IA’s Standards Committee with input from members. This ensures that the Code is up to date with current practices of conducting market research and that it adequately protects research participants. This Code is an excellent example of how market researchers should manage market research projects throughout the process. You can read this Code here.

Albrecht, M. G., Green, M., & Hoffman, L. (2023). Principles of Marketing. OpenStax, Rice University. CC BY 4.0

Insights Association. (2023, November 1). Code of standards. Insights Association.

II

Learning Objectives

In module 2, students will learn how to:

A recommended set of five steps should be followed in order to accomplish the goals of gathering insights and finding solutions through market research. While following a set of steps may seem like a lot of work or take too long to solve problems, the time invested in going through the steps will ultimately pay off in the form of research-driven solutions. This module outlines the five steps to designing a market research project; however, individual steps will be covered in greater detail throughout the book.

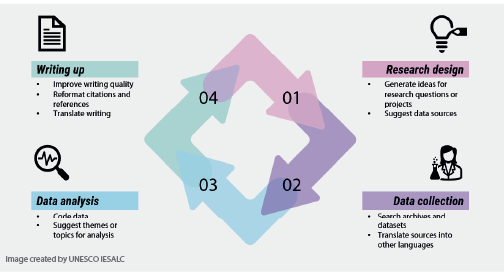

Since most organizations and businesses have multiple problems, the first step is to gather information to define the market research problem(s). If the problem is not defined correctly, then the research design will not be constructed accurately, and all of the steps to designing a market research problem will be inaccurate. The pathway to defining a market research problem is explored in module 5.

Once the research problem has been defined, and it has been determined that primary research is required, the next step in the marketing research process is to do a research design. The research design is a “plan of attack.” It outlines what data will be gathered and from whom, how and when the data will be collected, and how it will be analyzed it once it’s been obtained.

Some questions that should be asked at the research design phase are:

These are issues that a researcher should address in order to meet the needs identified.

Data collection is the systematic gathering of information that addresses the identified decision problem. Picking the right method of collecting data requires that the researcher understand the target population and the design picked in the previous step. There is no perfect method; each method has both advantages and disadvantages, so it’s essential that the researcher understand the target population of the research and the research objectives in order to pick the best option.

Once it has been determined the methodology of the research – qualitative and / or quantitative – the management and implementation of the data collection process will begin.

Albrecht, M. G., Green, M., & Hoffman, L. (2023). Principles of Marketing. OpenStax. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

For primary research, the collection of information from a sample of the population through qualitative and/or quantitative methods must be designed.

Quantitative research is typically used when a larger sample size is required and is measuring numbers, figures or objective data. A common quantitative research tool is the survey. Surveys are the most frequently used method of collecting market research data and are covered in depth in module 7.

Qualitative research is used when opinions, feelings, motivations, or subjective data is identified as the focus of the market research design. One qualitative method for gathering more detailed responses from research participants is conducting one-on-one interviews. These interviews give the researcher the opportunity to ask specific questions that align with the respondent’s unique perspective, as well as follow-up questions that build on previously completed responses. Another advantage of conducting one-on-one interviews is that they give the researcher a deeper understanding of the respondent’s needs. The disadvantage of conducting personal interviews is that they can be time-consuming and only yield one respondent’s answers. Therefore, in order to obtain a large sample of respondents,the interview method may not be the most efficient method.

Another qualitative research tool is the focus group. A focus group is a small group of people, typically 8 to 10, who meet the sample requirements. They are asked a series of questions together and are encouraged to build upon each other’s responses by agreeing or disagreeing with the other group members. Focus groups are similar to interviews in that they allow the researcher, through a moderator, to get more detailed information from a small group of potential customers. Focus groups will be covered in detail in module 8.

Once the methods have been confirmed, the data collection will take place.

Albrecht, M. G., Green, M., & Hoffman, L. (2023). Principles of Marketing. OpenStax. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Step 4 involves analyzing the data to ensure it’s as accurate as possible. Data analysis is not covered in depth in this book, as the process of data analysis is dependent on the skills and resources of those doing the research, as well as the type of research that was done. For example, if someone has deployed an online survey via email, the analysis of the results may simply be reviewing the analytics in the survey software. If a survey was collected by hand, using a pen and pencil, typically the answers are manually entered into a survey analysis software. If a focus group took place, the facilitator should produce a report of the findings, that is often then analyzed along with a transcript or recording of the dialogue. If one has hired a market researcher to design and execute the project, the researcher would typically manage the data analysis and provide the raw data if requested.

Author removed at request of original publisher. (2022). Principles of Marketing – H5P Edition. BC Campus Open Education. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Albrecht, M. G., Green, M., & Hoffman, L. (2023). Principles of Marketing. OpenStax. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Bhattacherjee, A. (2012). Social Science Research: Principles, methods, and practices. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Burnett, J. (Ed.). (2011). Introducing Marketing. Global Text Project. CC BY 3.0

The last step in the market research process is putting everything that has happened into one document that can be easily understood by others, usually into a presentation and/or detailed report. Sometimes the findings can reveal negative aspects of the organization or business, and it can be challenging to share that information with colleagues or partners. Marketers and those who are creating market research plans need to make sure that the steps of the research design are clearly explained and, in particular, that the recommendations are supported by the data findings. Analyzing the data obtained in market research involves transforming the primary and/or secondary data into useful information and insights that answer the research questions.

Albrecht, M. G., Green, M., & Hoffman, L. (2023). Principles of Marketing. OpenStax. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

III

Indigenous Communities (First Nations, Inuit, and Métis) in Canada require a different approach to understanding their markets depending on who you are, where you are, and the questions you are interested in answering (i.e. positionality). Reflecting on the questions proposed will help in engaging with this module. This module is written in a way that speaks directly to a non-Indigenous audience and may be helpful to Indigenous people who have been disconnected from their community. Specific considerations depend on your relationship with various Indigenous Communities.

Learning Objectives

Upon completion of this module, students will be able to :

By Abraham Francis

Before proceeding with market research on or with Indigenous Communities, the individual or team must consider their understanding of allyship with Indigenous Communities. Plenty of discussions attempt to define this concept, but remember that there is no one-size-fits-all approach, and it changes over time, so be flexible. There are many resources to draw upon, which is the first step in educating yourself to avoid making mistakes moving forward. Some summarized points provided below bring these concepts into dialogue with each other.

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/introductiontomarketresearch/?p=231#h5p-9

10 ways to be an ally to First Nations communities. (2022, July 2). Amnesty International Australia.

Dakota Swiftwolfe. (2019). Indigenous Ally Toolkit. Montreal Urban Aboriginal Community Strategy Network.

Jonas, S. (2021, September 30). Want to be an ally to Indigenous people? Listen and unlearn, say 2 community workers. CBC.

The Indigenous People of Canada have had a challenging relationship with both the Canadian Provincial and Federal governments, stemming from a history marked by physical, biological, and cultural genocide, as well as the dispossession of lands and intergenerational trauma. Three critical pieces of literature, shared below, contribute to helping define this historic pain body and directions forward to address the harm left behind and support Indigenous sovereignty and self-determination.

The first piece that recounts the painful narrative of residential schools is documented in the “Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future,” which outlines 94 calls to action spanning child welfare, health, justice, education, language, culture, reconciliation, museums, archives, youth, media, sports, research, newcomers, commemoration, missing children, burial information, and business (TRC, 2015). This report carefully intertwines research and personal stories, vividly portraying history and survivors’ experiences.

The second piece recounts the distressing history of Indigenous women, girls, and 2SLGBTQQIA individuals, who have been subjected to state-condoned abuses infringing on human and Indigenous rights, is illuminated in “Reclaiming Power and Place: The Final Report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls.” This report issues 231 Calls for Justice addressing the Government, Industry, Institutions, Services, Partnerships, and all Canadians (MMIW, 2019). Indigenous Women, Girls, and 2SLGBTQQIA individuals constitute one of the most vulnerable segments of Indigenous communities and play a crucial role in Indigenous societies. It is imperative to consider these histories and stories when the actions of Canadian federal or provincial governments may impact Indigenous rights, as well-intentioned efforts have the potential to cause significant harm to Indigenous Communities.

The third piece is to educate oneself on Indigenous Communities’ right to sovereignty and self-governance, a principle upheld by international laws, notably enshrined in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People (UNDRIP). Adopted during the United Nations’ 107th plenary meeting in 2007, the UNDRIP comprises 46 Articles that affirm Indigenous rights on a global scale (Assembly, 2007). The UNDRIP was endorsed by the Government of Canada in 2016 and, on June 21, 2021, received royal assent as an act and immediately came into force with a two-year action plan to meet the objectives in collaboration with Indigenous Communities (D. of J. Canada, 2021).

Assembly, U. G. (2007). United Nations declaration on the rights of indigenous peoples. UN Wash, 12, 1-18.

Canada, D. of J. (2021, June 22). Legislation to implement the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples becomes law [News releases].

National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (Canada). (2019). Reclaiming power and place: The final report of the national inquiry into missing and murdered indigenous women and girls. National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2015). Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future. Summary. Volume One. James Lorimer Limited, Publishers.

In one of the most significant statements about research on Indigenous People, Linda Smith (1999) makes the statement,

“[Research] is probably one of the dirtiest words in the indigenous world’s vocabulary. When mentioned in many indigenous contexts, it stirs up silence, it conjures up bad memories, it raises a smile that is knowing and distrustful. It is so powerful that indigenous people even write poetry about research.”

When we research Indigenous Communities, it’s essential to be mindful of their painful history, which requires time and understanding, as described in the allyship section. Smith’s work looks at the colonial origins of research and argues for decolonization. This led to the development of Kaupapa Maori Research, an approach where ideas and priorities come from the cultural context of her people. While Smith’s work inspired many Indigenous scholars, the concept faced the challenges of being stolen and applied to prioritize non-Indigenous communities’ comfort and status quo. Tuck and Yang (2012) affirmed that decolonization isn’t just a metaphor. It should center Indigenous Communities and their knowledge. Further, it requires addressing the historical pain body by returning Indigenous land and respecting Indigenous sovereignty and self-determination. Held (2019) looks at research from a different perspective, highlighting the conflict among Indigenous Scholars about whether Indigenous research by non-Indigenous Folks or Institutions is possible or impossible.

Data sovereignty is another consideration; Indigenous Communities own and control their data. This is a massive discussion with many layers about different kinds of data, including collection, validation, and interpretation, as well as sharing results from data. Researchers need to understand that statistics from censuses (quantitative) are only a tiny portion of the story and should be supplemented with community-level stories (qualitative). The First Nations Indigenous Government Center (FNIGC) provides some excellent guidance on this concept through OCAP®, which is described in detail below.

These are just the surface of this larger discussion, and community-level protocols should also be researched, depending on the scale of information needed. Further, the FNIGC provides training on their website to help students gain a deeper understanding and application of these concepts.

Held, M. B. (2019). Decolonizing research paradigms in the context of settler colonialism: An unsettling, mutual, and collaborative effort. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 18, 1609406918821574.

The First Nations Principles of OCAP®. (n.d.). The First Nations Information Governance Centre. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

Tuck, E., & Yang, K. W. (2012). Decolonization is not a metaphor. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, 1(1).

Smith, L. T. (2021). Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. Zed Books Ltd..

The highest level of information on Indigenous Communities can be obtained from Statistics Canada (StatCan), where you can search a variety of resources that have been developed. The most recent census is from 2021. The set of data from StatCan website that users can manipulate to answer high-level questions on the level of Canadian Federal, Provincial, and Municipality levels are on the page, “Indigenous identify population by gender and age: Canada, provinces, and territories, census metropolitan areas and census agglomerations” (Statistics on Indigenous Peoples, n.d.). Another high level of information can be found by exploring the regional office’s pages of Indigenous Services Canada (ISC) regional offices (Government of Canada, 2009) and First Nation Profiles of Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada (Government of Canada, 2008). This data should be cautiously read due to the lack of engagement from some Indigenous Communities.

The best information comes directly from Indigenous Communities or organizations that represent their interests on the national and regional levels. On the national-level Indigenous Organization, the Assembly of First Nations (AFN) carries the mission of “Advocating for the rights of and quality of life of First Nations people in Canada” and has an informative and well-supplied website with information on current issues and prepared reports (Assembly of First Nations, n.d.). There are regional organizations that operate across Canada; for Ontario, the Chiefs of Ontario (COO) is the regional organizing body that also has a great website for regional scale current issues and prepared reports (Chiefs of Ontario, n.d.). Lastly, it is great to go directly to Indigenous Communities’ websites to learn more about what is going on locally and find a way to connect with the community and their different resources and contacts. For example, the Mohawk Council of Akwesasne in Eastern Ontario has a great website that is well maintained (Mohawk Council of Akwesasne, n.d.). It is important to remember that Indigenous Communities have differing capacities, so the websites may not be up to date. It is always best to connect with someone from the community and develop a relationship who may be able to connect you with community level economic studies or other work.

Assembly of First Nations. (n.d.). Assembly of First Nations: Representing First Nation citizens in Canada. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

Chiefs of Ontario. (n.d.). Home—Chiefs of Ontario. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

Government of Canada. (2008, November 14). First Nation Profiles [Fact sheet; resource list].

Government of Canada. (2009, January 5). Regional offices [Organizational description; geospatial material; administrative page].

Mohawk Council of Akwesasne. (n.d.). Mohawk Council of Akwesasne – Proudly Serving All Akwesasronon. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

Statistics on Indigenous peoples. (n.d.). Retrieved June 23, 2023.

IV

Learning Objectives

In Module 4, students will learn how to:

As briefly mentioned in module 1, there are two main types of market research, primary and secondary research.

Primary research is conducted when new data is gathered for a particular product or hypothesis. This is where information does not exist already or is not accessible, and therefore needs to be specifically collected from consumers or businesses. Surveys, focus groups, research panels and research communities can all be used when conducting primary market research. The two most common primary market research tools, surveys and focus groups, will be covered more in depth in chapters 5 and 6.

Secondary research is also called ‘desk research’ as it can be done by reviewing existing sources typically through online databases and sources. Secondary research uses existing, published data as a source of information. It can be more cost-effective than conducting primary research.

Existing research can be used to establish the context and parameters for primary research, which can help give insights to the research project in its early stages. Secondary research can be useful for identifying problems to be investigated through primary research. Research based on secondary data usually precedes primary research.

Secondary research can:

This video from the University of British Columbia demonstrates some commonly used sources for secondary market research.

A number of market research companies exist in Canada who conduct research using a variety of tactics and then sell this data to interested parties. This is why secondary research is often less expensive, as these companies have experts whose job is to collect data, analyze and publish the results instead of embarking on your own journey of conducting your own primary research. Secondary research could have originally been collected for solving problems other than the one at hand, so they may not be sufficiently specific to your research problem.

It is imperative to carefully go through the secondary research to ensure that the methodology is sound and the source is trusted. Sometimes studies are commissioned to produce the result a client wants to hear—or wants the public to hear. Web research can also pose certain hazards. There are many biased sites that try to fool people that they are providing good data. Often the data is favourable to the products they are trying to sell. Beware of product reviews as well, as unscrupulous sellers sometimes get online and create bogus ratings for products.

The following inquiries can be used to evaluate the calibre and reliability of secondary research:

Ensure that a thorough review of any secondary research is done every time it is being considered to be used as part of a market research project!

The most popular source of secondary research in Canada is Statistics Canada. While exploring the more than 30 subjects of data from Statistics Canada can be overwhelming, it has rich data on Canadians over time. The basis for many Statistics Canada studies is the census, which is a survey in which every member of the population is ideally surveyed, rather than just a sample or portion of it. Currently, Statistics Canada conducts a census every four years, and the data gathered serves as the basis for many of the studies that are used in daily Canadian life. You can access all of Statistics Canada’s data for free, in both English and French, at statcan.gc.ca.

Market Research in Action

Alex owns a small chain of coffee shops, Java Life, in the Montreal, Quebec area. They are interested in ensuring that food produced locally features promimently in the coffee shop menu offerings. Alex is interested in access some data around diet and nutrition and food prices, but is unsure where to start. Alex’s friend works for a marketing company, and suggest that Alex review the Statistics Canada Food Price Data Hub. The information is free to access and includes updated information on the monthly Canadian average retail price of selected food items, food supply chain prices, and the Consumer Price Index (CPI) for food purchased from stores. With this information, Alex can get a better sense of the cost of food and how inflation may be affecting overall supply chain so they can make data-driven decisions about food for their Java Life shops.

Here is a short video from Statistics Canada about why census data is valuable secondary research.

Businesses that have digital properties on the internet have access to a wealth of digitally recorded web analytics data that can be mined for insights. Customer communications, particularly those with the customer service department, are another source of data that can be used. Loyal customers who provide feedback, criticism, or compliments are providing information that can serve as the basis for customer satisfaction research. Social networks, blogs, and other forms of social media have emerged as forums where customers discuss their preferences.

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/introductiontomarketresearch/?p=65#h5p-2

Author removed at request of original publisher. (2022). Principles of Marketing – H5P Edition. BC Campus Open Education.CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Albrecht, M. G., Green, M., & Hoffman, L. (2023). Principles of Marketing. OpenStax. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Statistics Canada (2023, November 23). Here’s Why You Should Use Census Data [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rhttC8OZl0I

Data can be categorized as either qualitative or quantitative. Exploratory in nature, qualitative research aims to learn what prospective customers believe and feel about a particular topic. It also helps identify potential hypotheses, while quantitative research seeks to validate these claims with hard data. Finally, quantitative research depends on numerical data to show statistically significant results.

The main differences between quantitative and qualitative research are represented in table below.

| Quantitative | Qualitative | |

| Data gathered | Numbers, figures, statistics objective data | Opinions, feelings, motivations, subjective data

|

| Question answered | What? | Why? |

| Group size | Large | Small |

| Data sources | Surveys, web analytics data

Tests known issues or hypotheses |

Focus groups, social media

Generates ideas and concepts – leads to issues or hypotheses to be tested. |

| Purpose | Seeks consensus, the norm

Generalizes data |

Seeks complexity

Puts data in context |

| Advantages | Statistically reliable results to determine if one option is better than the alternatives | Looks at the context of issues and aims to understand perspectives |

| Challenges | Issues can be measured only if they are known prior to startingSample size must be sufficient for predicting the population |

|

Sometimes market researchers will use a combination of both methods, and this approach is called mixed methods. For example, using a survey to gather information on the research topic and then using that survey to recruit participants for a focus group to probe the topic in more depth can be used.

This resource doesn’t go deeply into mixed methods, but the video below by Grad Coach goes into depth about qualitative, quantiative and mixed methods for any research project.

Albrecht, M. G., Green, M., & Hoffman, L. (2023). Principles of Marketing. OpenStax. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Grad Coach. (2021, September 27). Qualitative vs Quantitative vs Mixed Methods Research: How to Choose Research Methodology [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hECPeKv5tPM

V

Organizations and businesses tend to want to jump quickly to a solution, or number of solutions, to solve a problem. This makes sense, as problem solving is typically a key part of success in any sector. The challenge with this approach is that, quite often, the person who sees issues or opportunities in their work has unconscious bias towards the work, and sometimes ‘can’t see the forest for the trees’, as the saying goes.

Unconscious, or implicit bias, is bias that we all have as a result of our life experiences, and involves assumptions that can happen without one’s knowledge. Employees who are working to solve issues or look for new opportunities in their work, may have a hard time looking critically at the situation due to being so close to the work. This is where market research comes in. A marketer or market research consultant can offer a process to support the identification of a decision problem or hypothesis, and use market research to test and ultimately prove or disprove the decision problem. If a decision problem is not identified correctly, the research design will not be constructed accurately and that will affect every step of the market research project. It cannot be stated enough times that identifying the decision problem is the most important part of doing market research… so take the time to go through these steps.

Unconscious bias is not explored in depth in this resource, but this chapter on the topic as part of Universal Design for Learning (UDL) for Inclusion, Diversity, Equity, and Accessibility (IDEA) open educational resource clearly explains a number of biases.

There are four steps to identifying a market research decision problem that will be explored in this module.

Learning Objectives

In module 5, students will learn how to:

The first step in identifying a decision problem is to conduct some exploratory research, usually through informational interviews with important partners or staff members involved in the research effort. Asking at least three important people a series of open-ended questions will provide insights into the issues at hand. Develop a list of six to ten open-ended questions, ask the same questions in each interview, and make sure to record the answers.

Market Research in Action: Isabella

Isabella is thinking about selling her honey at an additional three farmers’ market in the area. She isn’t sure if the price that she charges now end up being profitable after the cost of driving to the markets and setting up a booth. Isabella decides to do some exploratory research and decides to identify three people – another farmer who is a friend, a coordinator at the market where she already sells her honey and her husband, who is also her business partner. Here are the questions that Isabella will ask these three people:

Isabella will record the answers of all questions so the answers can be reviewed as part of the next step.

Review the data collected in the informational interviews and consider the following points:

Market Research in Action: Isabella

After reviewing the answers from the three interviews, Isabella notices some themes from the interviews. These include:

Isabella decides that additonal market research is worthwhile, as there may be opportunities for increased profit and distribution.

Chiang, I.-C. A., Jhangiani, R. S., & Price, P. C. (2015, October 13). Research methods in psychology – 2nd Canadian edition. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

After you have the answers to the aforementioned queries, you should create a decision problem for your market research project. Usually, this decision problem takes the form of a question that will direct the market research design at every stage. The question should clearly state the issue that needs to be addressed.

Market Research In Action: Isabella

Isabella has identified that there are a number of decision problems that could be reviewed, but the one that would make the most impact on her future business would be understanding what is already happening at the other markets and if there is opportunity for a new producer. Once this information is determined, the Isabella can look into possible collaborations with other farmers and assessing the opportunity for online sales. For this market research project, Isabella’s decision problem will be “What is the potential market demand for expanding honey sales to three additional farmers’ markets in the local area?”

Chiang, I.-C. A., Jhangiani, R. S., & Price, P. C. (2015, October 13). Research methods in psychology – 2nd Canadian edition. Research Methods in Psychology 2nd Canadian Edition. https://opentextbc.ca/researchmethods/ CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Before you move into the market research project design, validate the decision problem with those who were interviewed, and others if required. Take them through the results from the informational interviews and confirm that this is the problem to be researched.

As part of this exercise, often multiple problems of opportunities are revealed. This is common but not all problems can be solved with one market research project. As well there are some problems that cannot be solved with market research, and those may be revealed in this process but need to be addressed in a different way.

Business problems such as having a purchasing process that involves too many steps, not paying employees a salary that is comparable in the industry, not having a unique selling point (USP) for your products or service, or selling a low-quality product or service can’t be solved with market research. For example, if you are able to hire staff through innovative and engaging recruitment efforts, but can’t retain staff for more than 12 months, the issue is probably not marketing but challenges within the company culture. Additional marketing to promote open positions won’t lead to retention of staff.

Additionally, there are some marketing problems that cannot be solved with research such as having staff who don’t understand how to write a marketing plan, or using the ‘spray and pray’ method of using one message on all of the platforms.

Taking the time to go through the steps of the identification of the decision problem will support a well-designed market research plan with the goal of finding solutions to the problem.

Market Research in Action: Isabella

Isabella now has her market research decision problem, and takes this back to her three interview candidates to get their feedback and make any adjustments as needed. Isabella also asks some members of the local farming assocation for their feedback on the decision problem.

Once Isabella is confident that she wants to move ahead with the market research and has confirmed the market research decision problem, she will move onto the next step of designing the research.

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/introductiontomarketresearch/?p=80#h5p-3

Burnett, J. (Ed.). (2011). Introducing Marketing. Global Text Project. CC BY 3.0

Kearney, D. B. (2022). Universal Design for Learning (UDL) for Inclusion, Diversity, Equity, and Accessibility (IDEA). CC BY 4.0

VI

Once it has been established that your decision problem justifies the creation of a market research plan, the next step is to determine the subject of the research as well as the target population and sample. This is an essential step in any market research process, whether it is qualitative or quantitative.

Learning Objectives

In module 6, students will learn how to:

Although a market researcher might want to include every possible person who matches the target market as part of the research project, it’s often not a feasible option, nor is it of value. If one does decide to include everyone, it would be a census of the population. Getting everyone in a population to participate is time-consuming and highly expensive, so instead marketers use a sample, whereby a portion of the whole is included in the research. It’s similar to the samples you might receive at the grocery store or ice cream shop; it isn’t a full serving, but it does give a good taste of what the whole thing would be like.

So how does one know who should be included in the sample? Researchers identify parameters for their studies, called sample frames. A sample frame for one study may be college students who live on campus; for another study, it may be retired people in Ottawa, Ontario, or small-business owners who have fewer than 10 employees. The individual entities within the sampling frame would be considered a sampling unit. A sampling unit is each individual respondent that would be considered as matching the sample frame established by the research. If a researcher wants businesses to participate in a study, then businesses would be the sampling unit in that case.

The number of sampling units included in the research is the sample size. Many calculations can be conducted to indicate what the correct size of the sample should be. Issues to consider are the size of the population, the confidence level that the data represents the entire population, the ease of accessing the units in the frame, and the budget allocated for the research.

The identification of the target population confirms the number of respondents and the way they are selected. If done correctly, general conclusions can be drawn about the views of the target population based on a small number of respondents. For example, when properly selected, a survey of 1,000 citizens can allow a researcher to draw conclusions about the views of all citizens in a country. If, on the contrary, there are mistakes in the selection of respondents, the results of the survey can be biased to the point of being useless.

The process of choosing participants for a market research study is known as sampling methodology in statistics. If the project is being managed by a market research firm, then a team of highly skilled statisticians will assist in choosing a sample from the target population by performing a series of mathematical calculations. The results of the validity and accuracy of professional surveys, for instance, are typically presented as part of the findings presentation.

For organizations and businesses who may be conducting the market research themselves, there are some key considerations to ensure that the sample selected is representative of the target population.

Market research project designs that indicate the right sample size often assume a 100% response rate. If a response rate is suspected to be lower, the sample size needs to be adjusted upwards. “A high response rate is important for drawing valid result conclusions. This is particularly the case if those who ignore a survey and would have answered differently than respondents. For example, in customer satisfaction surveys, those who are unhappy with the service may answer the survey to channel their anger and to ask for change, while those who liked the service may not bother responding. In this case, survey results are biased and the bias will be more important if the response rate is low,” (OECD, 2012).

Albrecht, M. G., Green, M., & Hoffman, L. (2023). Principles of Marketing. OpenStax, Rice University. CC BY 4.0

There are two main categories of samples: probability and nonprobability. Probability samples are those in which every member of the sample has an identified likelihood of being selected. Several probability sample methods can be utilized.

One probability sampling technique is called a simple random sample (SRS), where not only does every person have an identified likelihood of being selected to be in the sample, but every person also has an equal chance of exclusion. Many types of probablity samples are listed here, but it is recommended for businesses or organizations who are leading primary research themselves to select a simple random sample. A statistician is usually needed for most methods of selecting samples that go beyond a simple random sample in order to ensure that the number of subgroups compared, the measurement used, and the level of sampling error are all within acceptable bounds.

When simple random sample (SRS) is used, everyone in the population has an equal probability of being selected. For example, If a statistics teacher wants to choose a student at random for a prize, she could simply place the names of all the students in a hat, mix them up and choose one. Another example of SRS is if one chooses to give a number to every person in the population and then randomly select numbers from a hat or by using computer software.

There are a number of additional types of probability sampling methods, but as previously mentioned, they tend to be administered by market research professionals.

Market Research in Action: Daraja

Daraja is a university student living in Calgary, Alberta. She is pursuing a degree in business administration and is interested in putting her newly acquired marketing skills into action for the Mustard Seed, a food bank on campus that provides diverse food staples to students free of charge. Daraja is interested in what types of foods the students are most interested in having stocked at the food bank, particularly since some international students have a challenge to find diverse foods in stores close to campus.

Daraja would like to do a small survey of students but isn’t sure where to start. Daraja decides to do a simple random sample of the students who have used the food bank in the past three months.

If Daraja has all of the emails for the students, how could she ensure that the sample is randomly selected? What other considerations should Daraja think about when constructing her sample?

When it’s important for the sample to have members from different segments of the population, one should use a stratified random sample method. In this type of sample, the population is first divided into groups called strata by some characteristic. Then, using a simple random sample (SRS), people are randomly selected from each group. This method ensures that each group is represented.

Market Research in Action: Daraja

As previously described, Daraja would like to conduct a survey of users of the Mustard Seed food bank from the past three months, in order to understand what foods these users are interested in accessing at the food bank. If Daraja is interested in understanding the country of origin of each student (to understand their food preferences) as well as their frequency of food bank use (to determine regular versus occasional users), Daraja could select a stratified random sample. The country of origin and frequency of food bank use are the strata in this scenario.

Daraja would then:

Then Daraja would have a stratified random sample for the survey. What are some of the challenges for Daraja with this approach?

In cluster sampling, the population is divided into naturally occurring groups (or clusters). For example, groups could be clustered by country or postal code. After the clusters are formed, some clusters are randomly selected. Then all people within those clusters are surveyed.

Market Research in Action: Daraja

Daraja is interested in understanding the needs of the users of the Mustard Seed food bank, located on the university campus. If, for example, Daraja was interested in categorizing the population based on the student residences on campus, she may want to select a cluster sample. In order to do this, Daraja would:

Cluster sampling can be more practical and cost-effective than other methods, especially when the population is large and dispersed, as it allows for sampling based on naturally occurring groups such as students living in residence.

In systematic random sampling, after choosing a starting point at random, people are selected by using a jump number. For example, choosing teams in gym class by counting off by 3’s or 4’s, is an example of systematic sampling. (Flexbooks, cite here)

Market Research in Action: Daraja

Daraja is interested in surveying all of the students who used the Mustard Seed Food Bank over the past few months. If Daraja wanted to have a true random sample from this group, she could use systematic random sampling. She would:

This approach would offer a balance between randomness and ease of implementation. It allows for a representative sample to be drawn without the complexities involved in other methods, ensuring an unbiased selection from the population of students utilizing the food bank.

Albrecht, M. G., Green, M., & Hoffman, L. (2023). Principles of Marketing. OpenStax, Rice University. CC BY 4.0

CK-12 Foundation. (n.d.). CK12-Foundation. CK-12.

OECD (2012), “Good Practices in Survey Design Step-by-Step”, in Measuring Regulatory Performance: A Practitioner’s Guide to Perception Surveys, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Scholes, S. (n.d.). Introduction to Sampling Methods . OER Commons. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Convenience sampling and judgement sampling are two examples of nonprobability sampling that are available to researchers and which we will examine more closely. A nonprobability sample is one in which each potential member of the sample has an unknown likelihood of being selected in the sample. Research findings that are from a nonprobability sample cannot be applied beyond the sample.

The first nonprobability sampling technique is a convenience sample. Just like it sounds, a convenience sample is when the researcher finds a group through a nonscientific method by picking potential research participants in a convenient manner. An example might be to ask other students in a class you are taking to complete a survey that you are doing for a class assignment or passing out surveys at a basketball game or theatre performance.

One challenge with a convenience sample is selection bias, as the participants are chosen due to their easy access and not representative of the population. Since convenience samples might not reflect the population’s true diversity, findings from such samples might not be applicable or generalizable to broader populations or contexts. Another challenge with convenience samples are the risk of self-selection of participants. For example, potential survey respondents on a running trail may be selected since the researcher is at the edge of a park and is looking to get more information on park use, but this might not include folks who have mobility challenges, or parents pushing strollers who aren’t able to access the trail.

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/introductiontomarketresearch/?p=91#h5p-6

Market Research in Action: Daniel

Daniel works for Smoothtech, a mid-size technology company in the Greater Toronto Area who make specialized software and consumer apps for the sports and entertainment industries. Daniel is interested in learning more about how customers at the local theatre company obtain information from the playbill and if there would be interest in moving to a digital format.

Daniel thought that he could go to two Saturday matinees and stand inside the lobby to pass out surveys by the men’s washroom. This would be an easy place to find customers as they would be at the theatre already.

What are the challenges with Daniel using a convenience sample, particularly on a Saturday afternoon and by the men’s washroom. What biases may occur with this sample?

A judgement sample is a type of nonprobability sample that allows the researcher to determine if they believe the individual meets the criteria set for the sample frame to complete the research. A judgement sample involves the selection of participants based on the researcher’s judgement about who would be most informative or representative of the population. For instance, one may be interested in researching mothers, so the researcher would outside a toy store and ask an individual who is carrying a baby to participate. The biggest challenge with a judgement sample is the potential for bias, as the researcher’s judgement might unintentionally favour certain individuals or groups, leading to a skewed representation of the overall population.

Market Research in Action: Daniel

Daniel wants to ensure that he has representative feedback from all parties who might be impacted by the decision of the theatre company to move to a digital playbill, so he considers using a judgement sample. This step will allow Daniel to assess if each respondent would meet the criteria to participate in the research.

Daniel could approach a judgement sample in this way:

What are some of the challenges with gathering judgement sample, particularly one of those who are deeply involved in the theatre such as key partners, versus Facebook followers? What would be the benefits to a judgement sample?

In a voluntary sample, people “self-select” to participate in the survey. They may be interested in or feel strongly about the topic or they may want the perks or prizes for participating. There may be many motivations for them choosing to participate. The challenges with voluntary bias include self-selection bias, in that the volunteer is really excited for the prize and are not interested in providing a truthful response to the research. Another challenge with a voluntary sample is ensuring representation, as certain groups or demographics might be overrepresented or underrepresented, leading to findings that are not reflective of the broader population.

Here is a video from Pew Research Center on the recent increase in use of online nonprobability surveys, and its advantages and disadvantages.

References

Albrecht, M. G., Green, M., & Hoffman, L. (2023). Principles of Marketing. OpenStax, Rice University. CC BY 4.0

OECD (2012), “Good Practices in Survey Design Step-by-Step“, in Measuring Regulatory Performance: A Practitioner’s Guide to Perception Surveys, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Scholes, S. (n.d.). Introduction to Sampling Methods. OER Commons. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

VII

Learning Objectives

In module 7, students will learn how to:

Quantitative research in market research involves gathering and analyzing numerical data to understand market trends, consumer behaviour, preferences, and other measurable aspects. It focuses on statistical analysis, aiming to quantify opinions, behaviours, and patterns within one or more target markets. One of the most common methods for measuring quantitative research is the survey, and knowing how to design a survey is an important tool in the market researcher’s tool box.

When conducting quantitative research, it’s essential to consider the decision problem to gauge if this is the right method to help reach solutions. There are a number of different quantitative methods that are used for market research including:

In module 4, a chart was presented that illustrated the distinctions between qualitative and quantitative research. Both methods of research provide valuable insights to support decision problems, but there are some benefits to quantitative research:

Blackstone, A. (2012). Principles of sociological inquiry: Qualitative and Quantitative Methods. Open Textbook Library. CC BY-NC-SA

Chiang, I.-C. A., Jhangiani, R. S., & Price, P. C. (2015, October 13). Research methods in psychology – 2nd Canadian edition. Research Methods in Psychology 2nd Canadian Edition. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

DeCarlo, M., Cummings, C., Agnelli, K., & Laitsch, D. (2022, June 28). Graduate research methods in education (leadership): A project-based approach (Version 2.12.14.17-19.22). BC Campus. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

OECD (2012), “Good Practices in Survey Design Step-by-Step”, in Measuring Regulatory Performance: A Practitioner’s Guide to Perception Surveys, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Surveys are questionnaires with a series of questions centred around a particular topic; they are probably the first tool for market research that most of us think of. Their main use is to easily collect large volumes of quantitative data, though they can also collect some qualitative data.

Surveys are widely used in quantitative research for a variety of reasons. Firstly, they are a great way to collect a large amount of data from a large number of respondents at a relatively low cost, especially when compared to other qualitative methods like focus groups or informational interviews. Secondly, surveys can be administered in-person, online, or by mail. Thirdly, mailed and telephone surveys are less common than online surveys because fewer people find the motivation to fill out a survey and mail it in. Finally, a lot of cell phone numbers are unlisted, which makes it especially difficult to ensure that phone surveys reach a wide sample of the target population, especially those who do not have land lines.

Nowadays, a lot of surveys are made using online, subscription-based software programs like Qualtrics and SurveyMonkey, which are relatively inexpensive to use. These programs are specifically made for conducting online surveys and have robust features like question banks, skip-logic, and screener questions, as well as analytics that make it fairly easy to review both aggregated and individual responses. Some smaller organizations will create an online survey using free tools like Microsoft or Google forms. To set up some in-person interviews, you might need to budget for gas to drive around the province, other travel expenses like meals and lodging while on the road, and the time it takes to drive to and speak with each individual. As a result, surveys are relatively cost-effective.

Survey research also tends to be a reliable method of inquiry because surveys are standardized, in that the same questions, phrased exactly the same way, are posed to respondents. Other methods, like qualitative interviewing, do not offer the same consistency that a quantitative survey offers. This is not to say that all surveys are always reliable; a poorly phrased question can cause respondents to interpret its meaning differently, which can reduce that question’s reliability. The benefit of cost effectiveness is related to the survey’s potential for generalizability. Because surveys allow researchers to collect data from very large samples for a relatively low cost, survey methods lend themselves to probability sampling techniques.

Surveys are a popular method for gathering primary data because of their versatility. They allow the researcher to ask the same set of questions of a large number of respondents. The number of completed surveys divided by the total number of surveys attempted yields the response rate. Surveys can gather a wide range of data, both quantitative and qualitative. The questions can be simple yes/no questions, select all that apply questions, questions on a scale, or a variety of open-ended questions.

Although it can be fairly simple to draft some questions and put them into a software program, there are a series of steps, when followed, will contribute to a survey that directly addresses the market research decision problem. These steps are adapted from Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development’s “Good Practices in Survey Design Step-by-Step”, (OECD, 2012).

DeCarlo, M. (2018). Strengths and weaknesses of survey research. In Scientific inquiry in social work. essay, Open Social Work Education. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

OECD (2012), “Good Practices in Survey Design Step-by-Step”, in Measuring Regulatory Performance: A Practitioner’s Guide to Perception Surveys, OECD Publishing, Paris.

The first method of survey distribution is mailed survey. These are surveys that are sent to potential respondents via mail service,or ‘snail mail’. Mailed surveys were once more popular because they could reach every household. For example, every four years, Statistics Canada conducts a population census. The first step in that data collection is to send a survey through Canada Post to every household. The benefit of mailed surveys is that respondents can fill it out at their own convenience. The drawbacks of mailed surveys are the cost and timeliness of responses. Mailed surveys require postage to be paid to the recipient and back. This, combined with the cost of printing, paper, and envelopes, adds up to the cost of mailed surveys.

Also, because of the convenience to the respondent, completed surveys may be returned several weeks after being sent. Finally, some mailed survey data must be manually entered into the analysis software, which can cause delays or issues due to entry errors.

Phone surveys are conducted over the phone with the respondent; traditional phone surveys required a data collector to speak with the participant; however, modern technology permits computer-assisted voice surveys or surveys where the respondent is asked to press a button for each possible response. Phone surveys take a lot of time, but they allow the respondent to ask questions and the surveyor to request more information or clarification on a question if necessary. One drawback of phone surveys is that they must be completed simultaneously with the collector, which presents a limitation because there are set hours during which calls can be made. Another major drawback of phone surveys is the decline in landlines over the previous ten years and the demographic of folks who do have landlines – seniors – in contrast to those who only have a mobile phone. Using phone surveys can make it challenging to reach a diverse sample of respondents.

Surveys collected in-person can take place in a variety of ways: through door-to-door collection, in a public location, or at a person’s workplace. Although in-person surveys are time-intensive and require more labour to collect data than some other methods, in some cases it is the best way to collect the required data. One of the downsides of in-person surveys is the reluctance of potential respondents to stop their current activity and answer questions. Furthermore, people may not feel comfortable sharing private or personal information during a face-to-face conversation.

Digitally collected data has the advantage of being less time consuming and often more cost-effective than more manual methods; a survey that could take months to collect through the mail can be completed within a week using digital means. Electronic surveys are sent or collected through digital means and are an opportunity that can be added to any of the above methods as well as some new delivery options. Surveys can be sent through email, and respondents can reply to the email or open a hyperlink to an online survey. A letter can be mailed asking members of the survey sample to log in to a website rather than return a mailed response. Many marketers now use links, QR codes, or electronic devices to easily connect to a survey.

Professor Hernandez shares an overview of the four most common types of survey distribution in this short video.

Albrecht, M. G., Green, M., & Hoffman, L. (2023). Principles of Marketing. OpenStax, Rice University. CC BY 4.0

Bhattacherjee, A. (2012). Social Science Research: Principles, methods, and practices. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Blackstone, A. (2012). Principles of sociological inquiry: Qualitative and Quantitative Methods. Open Textbook Library. CC BY-NC-SA

Elon University Poll. (2014, September 26). Methods of collecting survey data [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hECPeKv5tPM

How a survey is designed will directly impact on the success on the market research project. Potential respondents must have knowledge about the survey topic and they should have experienced the events, behaviours, or feelings they are being asked to report. If one is asking participants for second-hand knowledge—asking counsellors about clients’ feelings, asking teachers about students’ feelings, and so forth—it should be clarified that the topic of the research is from the perspective of the survey participant and their perception of what is happening in the target population. A well-planned sampling approach ensures that participants are the most knowledgeable population to complete the survey.

Most surveys are made up of closed-ended questions that are measured against a scale. Closed-ended questions ensure that each respondent has to choose one of the provided answers and can ensure consistency and ease of data analysis. Open-ended questions are more qualitative in nature as they allow for the respondent to write their response freely and are not forced into answers that limit the range of their responses. Open-ended questions can provide helpful insights but take longer to answer and can be challenging to analyze across the responses, as the answers can be varied. It is recommended to include at least one open-ended question in a survey, but should be used sparingly. As mentioned in the previous chapter, survey testing will provide insights as to how many – or few – open-ended questions should be included.

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/introductiontomarketresearch/?p=111#h5p-8

Regardless of how a survey is distributed, it’s crucial to have the questions written with as few errors as possible. A survey can include any number and type of questions, and more complicated questions should appear only once users are comfortable with the survey.

Market Research in Action: Alex

Alex would like to create a survey for the current members of their coffee loyalty program, as they have noticed that sign-ups have decreased significantly over the past few months, and email open rates from current members have also been decreasing. After going through the steps to identify a market research program, they have identified it as , “What types of rewards do customers prefer within a loyalty program—discounts, free items, personalized offers, or experiential rewards?”. Alex has decided to create a survey for current loyalty program members and email it to them with an incentive. They have created a draft survey in SurveyMonkey and would like to test it with some employees and some marketing colleagues to ensure it is free of errors and biases.

Using common survey design errors, some questions that have errors and some proposed solutions are listed below to ensure the survey that Alex sends out to their customers will have a high completion rate and be directly related to the market research decision problem.

Alex suggested to begin the survey with a fairly simple question:

1. Do you like rewards?

This question, although related to the market research decision problem, is very general, as the term ‘rewards’ could mean many things, not only loyalty programs. Alex would be better to ask a more specific question related to the cafe’s rewards program in order to understand the benefits that are most valuable to their customers.

Alex suggested to include this question near the start of the survey:

2. State your annual household income:

This might not be an uncomfortable for everyone, but a lot of folks don’t like talking about how much money they make in a year, particularly if the survey is anonymous. This is why any demographic questions – such as address, phone number, email address, gender, income, etc. – should always be put at the end. The rationale for this is that respondents have already answered the bulk of the survey questions and will be more apt to not abandon the survey if there only these demographic questions remain.

One additional point about demographic questions is that they should only ever be asked if the answer is directly related to the market research decision problem. In the case of Alex’s survey, household income may be of interest in relation to the benefits of a loyalty program, but other more personal questions such as education level or gender might not provide insights into the decision problem. Also, Alex may already have the contact information for the loyalty member program in a database, do it’s not necessary to ask these respondents to fill it in again. In sum, only ask the demographic questions that are vital to the market research decision problem.

Alex wanted to really dive into the details of the other loyalty programs that the survey respondents are part of, so they suggested this open-ended question in the survey:

3. Please list the loyalty program that you use the most such as a grocery or gas loyalty program. Think about how many times you accumulate points every year with this program and list 3 to 5 benefits of this program.