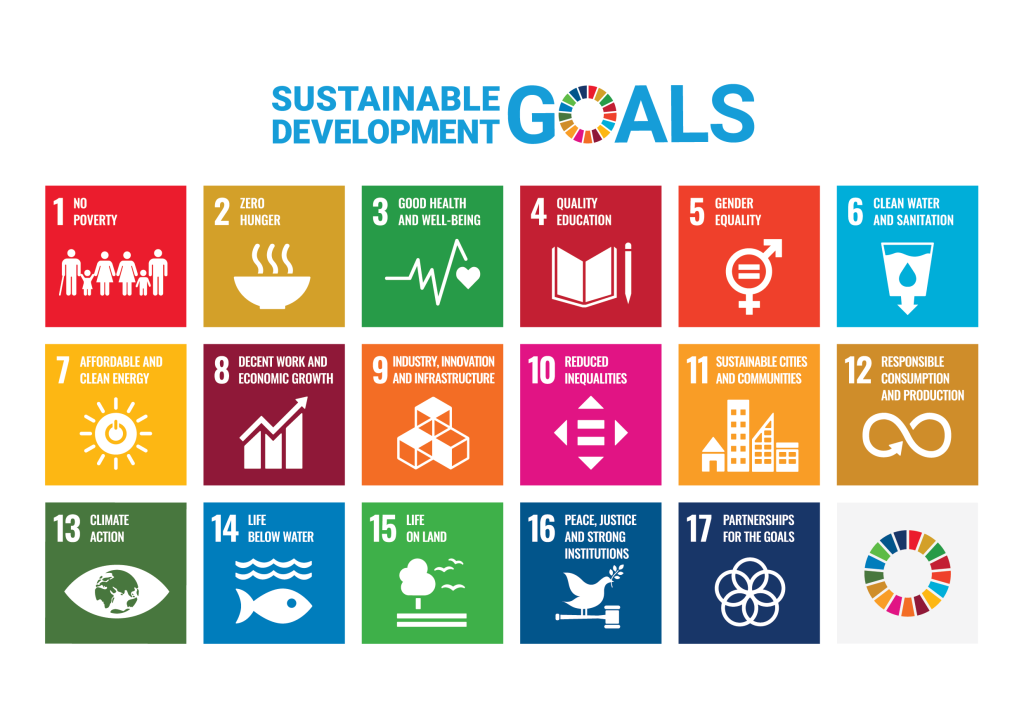

Despite growing recognition of the role that the financial sector could play in reaching countries’ climate and environmental goals, many countries, including the World Bank’s client countries, still do not have a clear picture of the actual interventions required to green the financial system. Greening the financial system can be understood in the context of both risk and opportunity. In the context of opportunity, greening the financial system refers to increasing financing flows into sectors that contribute to climate and environmental objectives. In the context of risk, greening the financial system refers to the management of climate-related and environmental financial risks.

As described in the World Bank’s Toolkits for Policymakers to Green the Financial System (2021), the creation of stable, sound, and transparent financial sectors requires mobilizing capital towards green growth objectives. The toolkits provide a detailed and practical implementation of six different areas (toolkits) to green the financial system. These areas are:

- Strategy and coordination

- Build skills and capabilities

- Financial regulation and central bank activities

- Increasing transparency

- Green(ing) FIs

- Green financial tools and instruments

Although the 17 toolkits discussed further are presented independently to clearly present the different options available to public authorities, there are significant synergies between the toolkits. In some cases, applying different toolkits together as a package may be more effective, depending on a country’s local context and priorities. For example, certain toolkits, such as those for creating a national platform on green finance or participating in national and international networks, could be a good place to start countries’ green finance journey and could be considered “cross-cutting” toolkits.

Strategy and Co-ordination

Strategy and co-ordination refers to the alignment of financial sector policies, regulations, and incentives with national environmental and climate goals by:

Developing a Green Finance Roadmap for the Financial Sector

Green finance roadmaps can provide the strategic framework to enable or accelerate a country’s ability to deliver on its climate and sustainable development goals while enhancing the financial sector’s competitiveness and economic resilience. A roadmap can help prioritize actions and coordinate activities across different stakeholders involved, including financial and environmental policymakers at the national and regional levels, supervisors, regulators and sector participants.

Developing a National Climate Finance Strategy

The process of defining a clear and actionable climate finance strategy is instrumental in delivering scaled investment to support the implementation of national climate plans. The strategy needs to ensure that over the long term, the public and private sectors can meet the required investment to respond to a country’s climate mitigation and adaptation needs. The strategy should clearly define the role of the private sector, and articulate how climate objectives can be mainstreamed into common financial sector policies and planning practices, such as through national budgeting, risk management and investment processes. The strategy should clearly articulate whether changes in financial sector regulation are needed to address financial sector market failures, such as missing or incomplete consideration and pricing of climate risks and opportunities.

Creating a National Platform or Taskforce on Green Finance

A national platform on green finance can be an important mechanism to ensure coordination between stakeholders and accelerate the growth of green finance. Countries may not have an organizational structure yet that links the key stakeholders, including the relevant ministries (e.g., environment, infrastructure, finance), central banks, financial supervisors, financial sector participants, other technical experts, or relevant external stakeholders. A platform could form a green finance program’s overarching coordinating, technical or implementation body. Depending on a country’s progress and objectives, this could take the form of a task force to design the basis of a country’s green finance strategy (e.g., China or the UK), provide the technical and institutional support to facilitate the implementation of specific goals, or function as a platform for key stakeholder engagement and development of initiatives (e.g., Netherlands).

Build Skills and Capabilities

Organizations can enhance understanding and awareness of climate/environmental risks and opportunities by:

Participation in Green Finance-Related International Networks

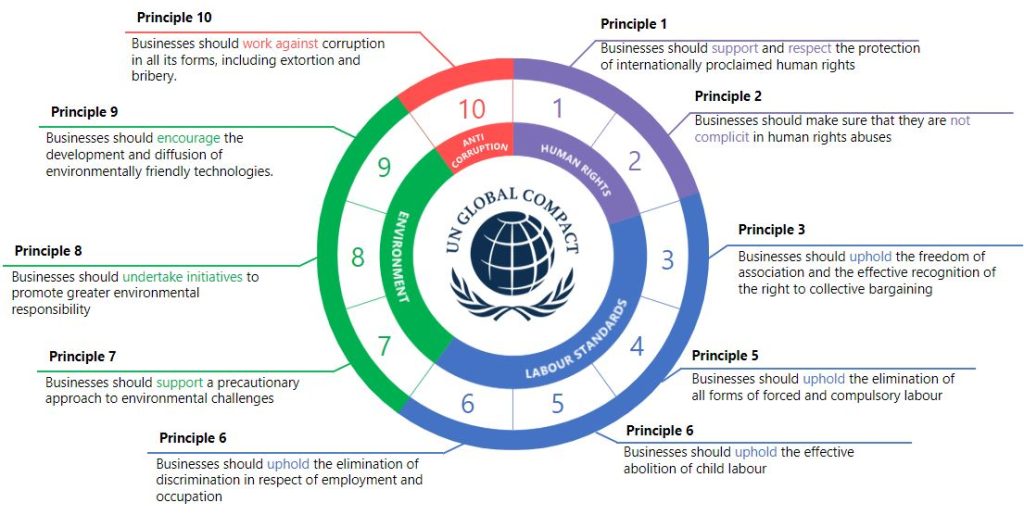

A multitude of international networks can be leveraged to support countries in their efforts to meet domestic climate goals and scale up green finance. Specific objectives range from enhancing green investments in the financial sector to capacity building or coordinating across financial regulators/supervisors. These networks have proven to be powerful mechanisms for sharing knowledge and best practices, signalling policy commitments, and facilitating the joint development of international standards.

An international field of cooperative authorities has developed as countries face similar challenges to mobilize green finance and address climate and environmental risk. Joining existing networks can help kickstart domestic action on green finance. Where it is not feasible to join networks, engaging with relevant standards as they develop to ensure alignment with international best practices is important. Many international regulatory bodies have now set up dedicated green finance-related working groups or task forces. Examples include the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, the International Association of Insurance Supervisors, the International Organization of Securities Commissions, the International Organization of Pension Supervisors and the International Accounting Standards Board.

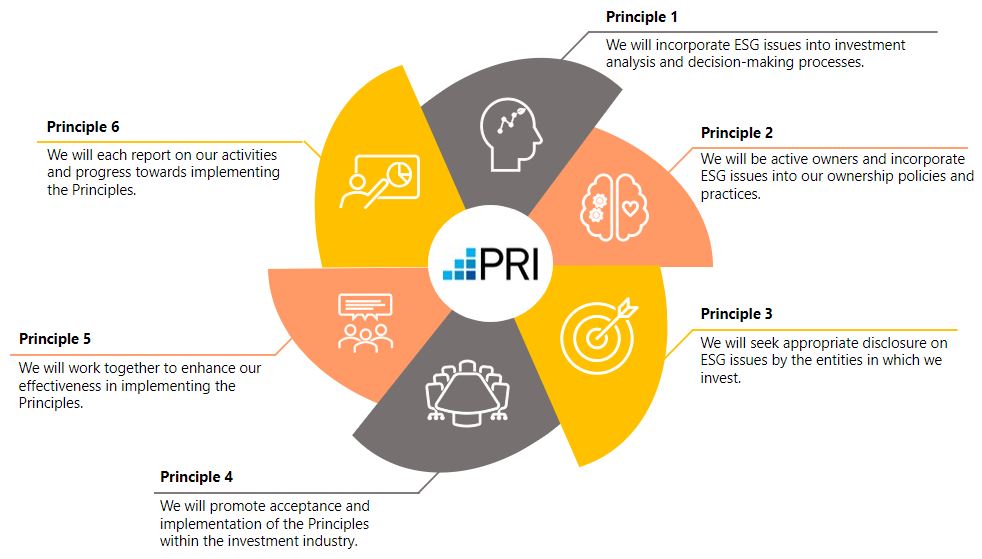

Supporting Financial Institutions’ Commitments to Align with the Paris Agreement

There is international consensus on the urgent need to align financial flows with the pathway towards carbon-neutral and climate-resilient development. Encouraging financial institutions to consider the Paris alignment of their portfolios, businesses, and strategy can help them capture the opportunities created by the low-carbon transition and manage the associated risks. Ultimately, Paris-aligned financial institutions can help fill the financing gap to meet (and raise the ambition) of a country’s climate goals.

Financial Regulation and Central Bank Activities

Financial regulation and central banks focus on improving the stability and soundness of the overall financial system. Their activities act as catalysts to change the behaviour of financial institutions to accelerate the low-carbon transition. This can be achieved by:

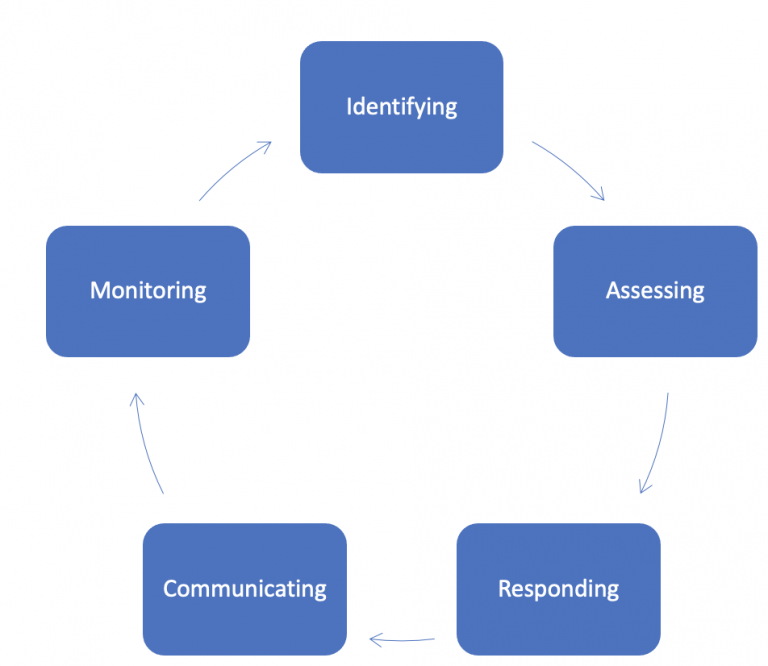

Conducting Climate-Related and Environmental Risk Assessment

A climate risk assessment, potentially including stress testing and scenario analysis, provides a fact base for dialogue between stakeholders and supports the improvement of risk management practices. Insights into the main climate-related financial risks will help macro- and micro-prudential supervisors focus their attention on the most relevant risks, as well as provide starting points for financial institutions to improve their internal risk management (e.g., mapping the main identified risks to their specific business model and balance sheet). The scope of assessments can potentially be expanded to include other environmental and social risks, including nature-related and biodiversity risks.

Incorporating Climate-Related and Environmental Risk into Supervisory Practice

Climate-related and environmental risks can have an impact on financial stability as well as the safety and soundness of financial institutions, or on how well financial markets are functioning. The consideration of these risks is therefore relevant to the mandate of central banks, the prudential supervisor, and capital markets authorities, which play a key role in ensuring that these are integrated into its supervisory practices and financial stability monitoring. A growing number of central banks, regulators, and supervisors across the globe have issued warnings on the impact of climate and environmental risks on the stability of their financial systems, or the impact on financial markets or financial market participants.

Issuing Supervisory Guidance on Climate-Related and Environmental Financial Risk

Issuing supervisory guidance is a key component of the supervisory response and plays an important role in clarifying authorities’ expectations in relation to regulated institutions’ response to climate-related and environmental risks. Setting supervisory expectations is an important mechanism to drive financial institutions to action and enhance their approaches to managing climate-related and environmental risk. Initiatives are underway in many jurisdictions to issue supervisory guidance, which tend to focus on (a combination of) several key areas: governance, strategy, risk management, scenario analysis and stress testing, and disclosure. The scope often covers different types of institutions. Banks and insurers, in particular, are often covered by the same supervisory guidance. Some may be even broader and also include asset managers, pension funds, or other institutional investors.

Exploring Greening of Central Banks’ Activities

Increasing attention is being paid to the potential of greening central banks’ activities and operations. While the thinking around many of these issues is still in the early stages, these are important options to consider when aligning central banks’ activities with the greening of the financial system. This toolkit provides a high-level overview of several options for central banks across certain key operations, including monetary policy and portfolio management. It is important to note that many of these options are still under review by the international central banking community, including under the Network for Greening Financial System (NGFS), and may not be deemed feasible (at this stage) depending on mandates, legal environments, or other individual assessments. It should also be noted that much of the experience to date stems from advanced economies, so emerging market and developing economies should carefully consider their local context before moving forward.

Increasing Transparency

Increasing transparency leads to long-termism in the financial system. The ultimate goal here is enhancing market transparency and understanding of climate-related and environmental risks and opportunities in order to inform investment processes and facilitate communication with clients, beneficiaries and other stakeholders – with the ultimate goal of facilitating the efficient allocation of capital in the transition to a low-carbon and climate-resilient economy.

Developing and Implementing Climate-Related and Environmental Disclosure and Reporting Standards

Investors and lenders need adequate information on climate-related and environmental risks and opportunities to understand, price and manage the risk in their portfolios and operations. Climate-related and environmental financial disclosure of both financial institutions and corporations in the real economy is imperative in providing the necessary information for financial market actors to consider climate or environmental-related risks and opportunities and align their capital accordingly. These disclosures have many uses in the investment process. For example, the information disclosed can be integrated into a valuation model, used for screening, to inform thematic investments, or to measure the impact of companies and/or funds. Public disclosure will be an additional incentive for firms to step up their efforts in this space.

Developing and Adopting a National Green Taxonomy

A green taxonomy offers a uniform and harmonized way of determining what economic activities can be considered environmentally sustainable. The World Bank is developing a series of Country Climate and Development Reports, which is expected to present a typology of decarbonization and adaptation policies. This may be a useful reference in the future to inform the development of a country’s green taxonomy.

It can perform a variety of functions:

- be a core building block of a country’s green finance objectives;

- support financial actors in making informed decisions on environmentally friendly investments, scaling up finance for climate mitigation, adaptation and other environmental goals;

- facilitate reliable and comparable disclosures relating to sustainability risks and opportunities;

- provide a consistent starting point for standard setters and product developers; and

- enable tracking and reporting of public expenditures and/or private investments addressing specific environmental or climate goals.

A taxonomy is an important complement to actions taken by authorities to align environmental regulations and fiscal policy to support greening of the real economy. A taxonomy can further promote market integrity by reducing “greenwashing.” It also reduces fragmentation resulting from market-based initiatives and national practices which lack coherency.

Greenwashing occurs in many different forms, and regulatory bodies are increasingly focused on ensuring that accurate information is provided – particularly in relation to climate change. For example:

The EU has developed several different requirements on what can be labelled as a sustainable or “Paris-aligned” activity or investment product.

In June 2022, the Australian Securities and Investment Commission (ASIC) released guidelines on avoiding greenwashing in sustainability products and has made action against greenwashing one of its enforcement priorities for 2023 and 2024. In 2023, ASIC sued several financial institutions for greenwashing.

In addition, international guidelines to prevent greenwashing in climate reporting have been provided by the UN Integrity Matters Report, which was focal during COP27.

Green(ing) Financial Institutions

Greening financial institutions refers to improving risk-adjusted returns of green investments, support policy reforms, and catalyze new markets for green growth.

Greening a National Development Bank or Other Domestic Public Finance Institution

As the link between domestic governments, international finance and local private sector actors, National Development Banks (NDBs) and other domestic public finance institutions occupy a key position in the green finance landscape. Even if NDBs are often small in size, these institutions can already have a major influence on the country’s development and infrastructure as well as the government’s climate-related plans and policies, due to their proximity to government. A much-needed additional benefit in response to the COVID19 crisis is that NDBs can play an important countercyclical role, providing credit to compensate for a temporary reduction in loans from private sector financial institutions during times of economic downturn. NDBs generally have the institutional support from governments and the understanding of local sectors needed to provide technical support and mobilize (private) investments. Therefore, instead of creating a new entity, governments could adapt existing public banks to increase and mainstream green finance within their operations. The focus may primarily be on development banks, but this could equally apply to public banks operating as infrastructure, industrial or commercial banks.

Creating a National Green Finance Entity or Green Bank

Public sector funding alone cannot meet the financing needs to achieve climate and environmental objectives. Dedicated national green finance entities or green banks can address the need for increased domestic green finance, with a specific focus on scaling up private finance. These entities could be considered as a type of public Strategic Investment Fund (SIF), providing debt or equity financing for specific green objectives.

Green Financial Tools and Instruments

Green financial tools and instruments lead to improving risk-adjusted returns of green investments, supporting policy reforms, and catalyzing new markets for green growth. There are many ways to achieve it:

Stimulating Corporate Green Bond Issuance

Standards and guidance by regulatory bodies can raise visibility and awareness of green bonds as well as guide the bond issuance process. This can include guidance on (or requirements for) definitions, management and use of bond proceeds, reporting, and incentive measures. Regulators and policymakers have several tools at their disposal to drive the development of green bond markets and stimulate domestic bond issuance.

Issuing Green Sovereign Bonds

Green bonds have the potential to provide a strong signal of a country’s commitment to meeting its climate goals and green growth objectives. They could be an effective tool for governments in raising capital to finance their NDCs or sustainable projects, and there may be numerous other benefits to issuing a green sovereign bond in addition to attracting finance. For example, they can help governments support local green finance market development by raising the profile of green bonds with potential issuers. Sovereign green bonds that have been issued in emerging markets to date have had a slightly longer maturity profile than the sovereign’s conventional bond portfolio; in addition, some emerging markets have been able to further diversify their investor base through the issuance of certified green bonds, tapping into growing global investor interest in these assets.

Promoting Use and Development of Blended Finance Products for Green Finance Purposes

Given the limited availability of public/concessional finance, blended finance mechanisms can help a country bridge the financing gap for its green finance objectives. In situations where private investments are not commercially viable due to high risks or non-commercial returns, suitable financial structuring through blended finance can unlock private investment. Blended finance aims to attract commercial capital toward projects that benefit society while providing financial returns to investors. Blended finance can help mitigate (perceived or actual) risks or uncertainties associated with new, unproven technologies or first-of-their-kind projects by shifting the investment risk-return profile with flexible capital and favorable terms. It helps address specific investment risks and rebalance risk-reward profiles of pioneering impact investments so that they have the potential to become commercially viable over time.

Sustainability-linked bonds are instruments which incentivize the borrower’s achievement of ambitious, predetermined sustainability performance objectives, measured using key performance indicators. Sustainability-linked bonds are different from green bonds in that it is a “performance-linked” instrument (rather than a “use-of-proceeds” instrument), with interest rates or a refinancing mechanism tied to achieving sustainable goals. Unlike green bonds, proceeds of sustainability-linked bonds are not required to be ringfenced. A sustainability-linked bond is a relatively new type of instrument but is increasing in popularity as a way to align borrowers’ sustainability profile with lending terms.

Watch this video to learn more about the role of green bonds in financial markets.

One or more interactive elements has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view them online here: https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/internationaltradefinancepart3/?p=358#oembed-1

Source: CNBC. (2021, May 28). How the $1 trillion green bond market works [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ruXLhpXvhOE

Examples of Key Blended Finance Categories

Guarantees and Insurance

Government authorities can offer guarantees to pay an agreed-upon amount of a loan or other financial instrument in the event that the guaranteed party cannot reimburse the claims or a project otherwise fails. Guarantees are flexible instruments which can be tailored to different circumstances and types of risk. Providing tailored insurance products needed to hedge specific types of risk can provide further assurance for private investors.

Green Credit Lines

Public (finance) authorities can provide green credit lines to commercial banks, which can be on-lent to end-borrowers for low-carbon projects. Such credit lines aim to demonstrate the commercial viability of green financing as an attractive business model, thus laying the basis for a self-sustaining market for financing different types of projects, for example, sustainable energy and energy efficiency projects.

Co-Lending and Credit Enhancement

Public authorities can directly co-invest alongside a commercial bank in green projects to improve project economics. This funding can have different structures, terms and longer tenors. Taking a subordinated position or providing first-loss capital structures can further mitigate project risks and provide additional incentives for private players to step into the market.

Stimulate Origination of Green Loans or Sustainability-Linked Loan Products

The green loan market provides significant potential to scale up green finance activity. This can be a core aspect of increasing banks’ involvement in the green finance market and simultaneously supporting the demand side. The banking sector’s green lending activity is often still limited and labels for green lending products are missing. A key category of green loan products is green mortgages, meaning a bank or mortgage lender offers a house buyer preferential term if they can demonstrate that the property meets (or will meet) certain environmental or energy efficiency standards. Other examples of the main categories include loans for energy efficiency improvements, renewable energy, sustainable agriculture practices, climate change adaptation or clean transportation financing.

To read more about implementation, checklist and examples of these 17 toolkits, download the World Bank publication,

Toolkits for Policymakers to Green the Financial System [PDF].

Attributions

“22.3 World Bank Toolkit for Green Financial Systems” is adapted from “Toolkits for Policymakers to Green the Financial System” by Finance, Competitiveness, and Innovation Global Practice, World Bank Group, © 2021 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank, and published on the World Bank Open Knowledge Repository under a CC BY 3.0 IGO license.

is the current account,

is the current account, and

and  are the export and import of goods and services respectively,

are the export and import of goods and services respectively, is net income from abroad, and

is net income from abroad, and is the net current transfers.

is the net current transfers.

nearly equals

nearly equals  .

.

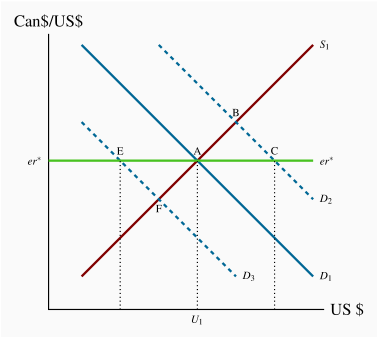

. There would be a free market equilibrium at

. There would be a free market equilibrium at  if the supply curve for U.S. dollars is

if the supply curve for U.S. dollars is  and the demand curve for U.S. dollars is

and the demand curve for U.S. dollars is  . The central bank does not need to buy or sell U.S. dollars. The market is in equilibrium and clears by itself at the fixed rate.

. The central bank does not need to buy or sell U.S. dollars. The market is in equilibrium and clears by itself at the fixed rate.

. Canadians want to spend more time in Florida to escape the long, cold Canadian winter. They need more U.S. dollars to finance their expenditures in the United States. The free-market equilibrium would be at B, and the exchange rate would rise if the Bank of Canada takes no action.However, with the exchange rate fixed by policy at

. Canadians want to spend more time in Florida to escape the long, cold Canadian winter. They need more U.S. dollars to finance their expenditures in the United States. The free-market equilibrium would be at B, and the exchange rate would rise if the Bank of Canada takes no action.However, with the exchange rate fixed by policy at  .The supply of U.S. dollars on the market is then the “market” supply represented by

.The supply of U.S. dollars on the market is then the “market” supply represented by  ), which reduces the monetary base by that amount. The lower monetary base pushes domestic interest rates up and attracts a larger net capital inflow. Higher interest rates also reduce domestic expenditure and the demand for imports and for foreign exchange. The exchange rate target drives the Bank’s monetary policy, which in turn changes both international capital flows and domestic income and expenditure.

), which reduces the monetary base by that amount. The lower monetary base pushes domestic interest rates up and attracts a larger net capital inflow. Higher interest rates also reduce domestic expenditure and the demand for imports and for foreign exchange. The exchange rate target drives the Bank’s monetary policy, which in turn changes both international capital flows and domestic income and expenditure. ? The market equilibrium would be at

? The market equilibrium would be at  . At the exchange rate at

. At the exchange rate at  . To defend the

. To defend the  is required for long-run equilibrium in the foreign exchange market and the balance of payments. As reserves start to run out, the government may try to borrow foreign exchange reserves from other countries and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), an international body that exists primarily to lend to countries in short-term difficulties.

is required for long-run equilibrium in the foreign exchange market and the balance of payments. As reserves start to run out, the government may try to borrow foreign exchange reserves from other countries and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), an international body that exists primarily to lend to countries in short-term difficulties.

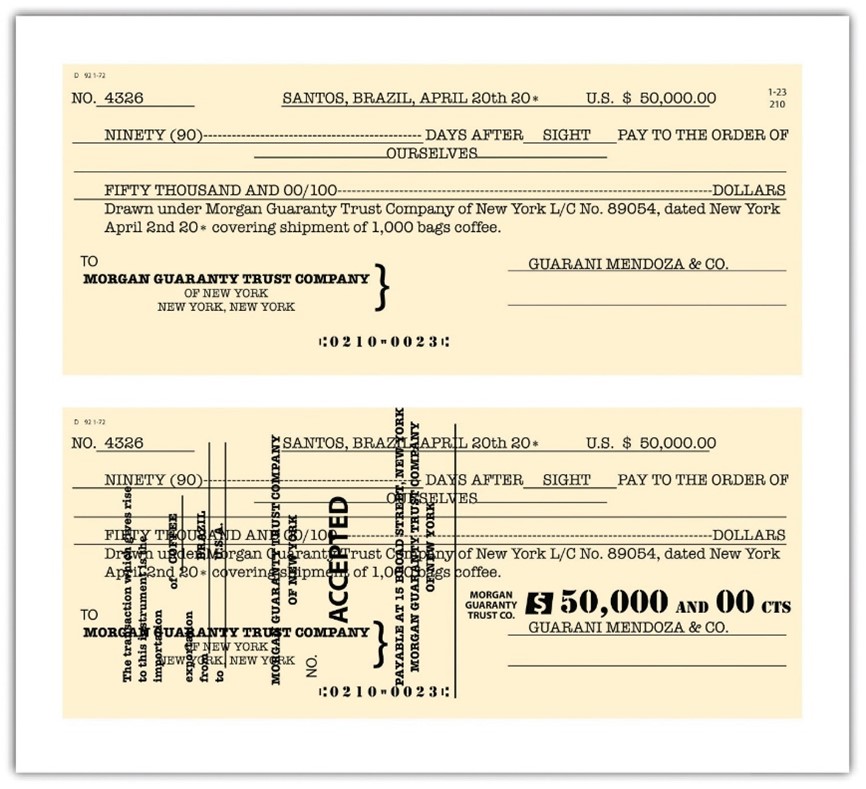

, it would have cost Starbucks

, it would have cost Starbucks  to purchase the reals needed to receive the one million pounds of coffee beans.

to purchase the reals needed to receive the one million pounds of coffee beans. for one million pounds of coffee beans, it would not have known what the coffee beans would cost the company in terms of U.S. dollars.

for one million pounds of coffee beans, it would not have known what the coffee beans would cost the company in terms of U.S. dollars. for the coffee beans. For example, suppose the dollar appreciated so that the exchange rate was

for the coffee beans. For example, suppose the dollar appreciated so that the exchange rate was  in July 2021.

in July 2021. .

. in July 2021, then the coffee beans would cost Starbucks

in July 2021, then the coffee beans would cost Starbucks  . This uncertainty regarding the dollar cost of the coffee beans Starbucks would purchase to make its lattes is an example of transaction exposure.

. This uncertainty regarding the dollar cost of the coffee beans Starbucks would purchase to make its lattes is an example of transaction exposure. . If the Costa Rican colón depreciates to 600 colones to the dollar, then the asset has a value of only $200,000 when translated using this exchange rate.

. If the Costa Rican colón depreciates to 600 colones to the dollar, then the asset has a value of only $200,000 when translated using this exchange rate.