2

Communication & Culture

mediatexthack

What is communication, why do we communication, how do we communicate, and to what end, are all questions we ask in the study of communication. At its most basic, communication is the exchange of information and meaning. We are constantly communicating, in a wide range of different contexts, such as with each other (interpersonal communication), with different cultural groups or subgroups (intercultural communication), or to large audiences (mass communication), just to name a few. However, to understand communication, we need to understand the place of communication in culture.

Culture as a term is widely used in academic as well as in daily speech and discourse, referring to different concepts and understandings. While the term originally stems from ancient Greek and Roman cultures (Latin: cultura) it has various dimensions today built from the different needs and uses of each field, be it anthropology, sociology or communication studies. For communication studies, we might start by defining culture as a set of learned behaviours shared by a group of people through interaction.

Cultures are not fixed, monolithic entities, but are fluid, always changing and responding to pressures and influences, such as the changing experiences of its members, or interaction with other cultures. However, to its members, the artefacts and even the existence of cultural behaviours and schemas may seem invisible or unremarkable. A culture may even have within it certain subcultures which exist within the main cultural framework of a society, but share within it specific peculiarities or modalities that also set it apart from the mainstream. These subcultures may continue to exist for many years or only a short period of time. They may die out, or may become incorporated into the mainstream as part of this ongoing evolution of culture.

While there are specific differences to each culture, generally speaking, cultures share a number of traits, such as a shared language or linguistic marker, definition of proper and improper behaviour, a notion of kinship and social relationship (i.e.: mother, friend, etc), ornamentation and art, and a notion of leadership or decision making process.

Culture and society, though similar, are different things. Cultures are defined by these learned behaviours and schemas. Societies at their simplest can be defined as groups of interacting individuals. However, it is through this interaction that individuals develop and communicate the markers of culture, and so in human societies, it is very difficult to separate out ‘culture’ and ‘society.’

And thus we come back to the role of communication within culture. The idea of culture as something that is shared means that it is vital to understand culture and communication in relation to one another. The relationship between culture and communication, in all its forms, is tightly interwoven and interlinked. We can see that communication enables the spread and reiteration of culture. Both communications and the media propagate the values and schemas of a culture through the repeated interaction and exchange enabled by the communications process.

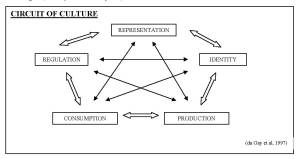

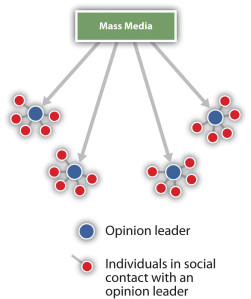

Notice the emphasis on repeated there: it is not in single instances of communication that culture is made, but rather in the repeated exchange of information and the reinforcement of the ideals and values it embodies, all conveyed within a particular moment. One way we can think about this complex interplay is by looking at du Gay, et al (1997) notion of the circuit of culture.

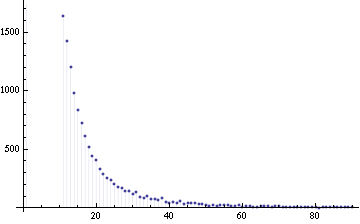

The circuit of culture is a way of exploring a product of a culture as a complex object that is affected by and has an impact on a number of different aspects of that culture.

Image (c) du Gay et al, 1997

It’s worth briefly going through each of these five variables on the diagram now, and then applying it to a familiar form of communication in culture. This text will return in later sections to deal more deeply with many of the idea’s that this diagram introduces.

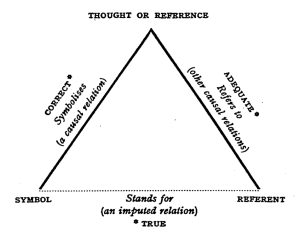

Representation – how is the meaning conveyed to the audience, user, or co-communicator? What signs, modes and discourses help convey the meaning – not only the ‘factual’ or informational meaning, but also the social meaning. For example, what does the colour pink represent in your cultural context?

Identity – refers to how meaning is internalized by the receiver or audience. Our identity is shaped by our culture, which creates a range of viable and non-viable identity options that are presented, refined and renegotiated through our communication and exchange of cultural objects. By consuming and displaying certain communicative texts and strategies, we are both claiming certain identity positions, and simultaneously rejecting others.

Production — here refers to the production of meaning. Meaning can be produced and reproduced in a number of ways. An individual may produce meaning about themselves in the way they dress or wear their hat. Apple™ produces meaning about itself in the way they design and build the iPhone™. A terrorist organization may produce meaning about itself by making videos they put on Youtube. This act of meaning production may be unproblematic within mainstream culture, and help maintain the hegemony, the dominance of a particular set of schema or values. Alternatively, this production may challenge dominant beliefs or values in some. A pop culture example of this might have been early Lady Gaga, whose mode of dress was confrontational because it deviated from existing cultural schema about appropriate dress for someone of her class, race, gender and occupation.

Consumption – The flip side of production is consumption. Consumption of texts, whether they be an outfit, a conversation, or a pop-song, reflects cultural values and expectations – conforming to values and expectations leads to unproblematic consumption – it’s what is expected, it fits our internalized schema. Texts that do not fit this schema are confronting, challenging, even shocking. To continue to use Lady Gaga as an example, when she released a nine-minute long music video centered around a narrative of female violence, it was shocking both in terms of its format (which wasn’t standard MTV fare) and its narrative structure.

Regulation – finally, regulation refers to the forces which constrain the production, distribution, and consumption of texts. These forces may be explicit, such as the television broadcasters code of conduct, or they may be implicit, such as the blogger litmus test of ‘would you say this in front of your mother?’

Finally, linking together these areas are these arrows – the arrows are very important, because as du Gay says, none of these variables can really be considered in isolation. It would be like looking only at the tyres to try and figure out why your car isn’t running. So it is important, when considering communication within a cultural context, to remember that there are multiple factors influencing the production of text and meaning. These factors may support the text, reinforce a cultural position, or alternatively, they may challenge or confront a cultural schema.

du Gay’s model is regularly applied to analysing the interplay between communication and culture within one cultural situation. However, with the globalisation of the media and communication landscape, it is becoming increasingly important to think about the specificities of intercultural communication.

Discussion

- How would you explain what culture is in your own words?

- Choose a form of communication or a media text, and see if you can apply the five variables du Gay suggests to understand that example.

References

du Gay et al. (1997) Doing Cultural Studies: The story of the Sony Walkman Milton Keynes: Open University; Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.