COMMON PHYSICAL CONCERNS

Factors impacting health

John Simpson R.P.N., M.Ed. (Special Education)

The life expectancy of people with intellectual disabilities is increasing. This is particularly noticeable for persons with Down syndrome, for whom the average life expectancy has risen from 26 years in 1983 to 55 years today, and many now live into their 60s and 70s (Emerson & Baines, 2010; National Association for Down Syndrome, 2012; Ouellette-Kuntz et al., 2004). Severity of disability affects longevity, however, and life expectancy tends to decrease as the severity of intellectual disability increases. Largely this occurs because people with severe intellectual disabilities experience a greater prevalence of associated health conditions such as severe mobility impairments, seizure disorders, vision and hearing impairments, swallowing difficulties, and inability to independently feed oneself (Ouellette-Kuntz et al., 2004). Epilepsy, for example, affects 22% to 33% of all people with intellectual disabilities, but increases as the severity of disability increases; half of all people with severe intellectual disabilities have epilepsy (Royal College of Nursing, 2006). This compares to a prevalence rate of about 0.5% for the general population.

Individuals with mild intellectual disabilities have an average life expectancy that is near that of the general population. When death does occur, it is commonly due to the same age-related health conditions that take the lives of members of the general population: cardiovascular disease, cancer, stroke, respiratory conditions, and diabetes-related complications (Horwitz et al., 2000). Still, while the overall life expectancy of people with intellectual disabilities is increasing, it remains about 10 years less than that of the general population. On average, people with intellectual disabilities have twice as many health conditions as others, and are from three to six times more likely to die from preventable causes (Department of Health, 2009; Havercamp, Scandlin & Roth, 2004). In fact, in a review commissioned by Britain’s Department of Health, 90 of 244, or 37%, of the deaths that were reviewed were found to be avoidable (Heslop et al., 2014).

In this chapter, we discuss the overall health status of people with intellectual disabilities and mental illness as well as factors that have an impact on health status and lifespan. We describe health and wellness challenges of particular importance to dually diagnosed people and identify strategies for assisting people who are experiencing specific challenges. The importance of including people with intellectual disabilities in health promotion programs and activities is also discussed.

There is broad agreement that people with intellectual disabilities, on the whole, have poorer health, greater health needs, and shorter lives than the general population. However, evidence shows time and time again that the considerable health needs of people with intellectual disabilities are often under- or undiagnosed, or poorly managed (Balogh et al., 2008; Department of Health, 2001; Emerson, 2011; Emerson & Baines, 2010; Morin et al., 2012). For example, the proportion of extracted teeth to filled teeth for people with intellectual disabilities has been reported to be higher than in the general population, indicating that intellectual disability is a risk factor that increases the likelihood of extraction. When Special Olympics Inc. screened 3,500 of its athletes at the Dublin World Summer Games, they found that:

- 30% failed hearing tests (this is six times greater than the rate in the general population)

- 35% had obvious signs of tooth decay, while 53% showed clear evidence of gum disease

- 12% reported tooth or mouth pain at the time of examination (in contrast with about 2% of the general population reporting pain at the time of dentist visits)

- 33% required corrective lenses, but only half of them had glasses at the time of examination

- 50% of the athletes had one or more foot diseases or conditions

- All of them (who had an average age of 24.7 years) had high rates of low bone mineral density (increasing the risk for fractures), comparable to rates reported in women aged 65 and older (Corbin, Malina, & Shepherd, 2005)

Health Status

Health Status

Key Points for Caregivers

Those who support and care for persons with intellectual disability can get clear signals from findings of research with Special Olympic athletes.

- Arrange routine vision and hearing examinations, particularly for age-related deterioration. Adults with Down syndrome are particularly likely to have vision and hearing problems. Those over the age of 30 are at increased risk for early development of cataracts, refractive errors such as near- and far-sightedness, and degeneration of the cornea.

- Encourage healthy dietary habits and promote or provide regular daily dental hygiene. Schedule routine dental appointments for cleaning, examinations, and maintenance of oral health. Individuals with intellectual disability are much more likely than individuals without disability to report that they have not had their teeth cleaned by a dental hygienist within five years, or that they have never had their teeth cleaned by a dental hygienist.

- Promote or provide proper foot care, ensuring that cleanliness is maintained, nails are correctly cut, and clean socks and proper-fitting shoes are worn. It’s been said that to determine how well a person with disability or dependency needs is being cared for, check the condition of his or her teeth and toenails. Although this form of assessment is far too simplistic, it does provide a telling measure.

- Provide well-balanced meals and regular weight-bearing exercise such as walking to promote overall health and bone maintenance. Individuals with Down syndrome as well as underweight or small-boned individuals are more at risk of bone loss and osteoporosis. Also at risk are individuals who experience delayed puberty or early menopause, which can accompany some conditions linked with intellectual disability.

When surveyed about the condition of their own health, individuals with intellectual disabilities are much more likely than individuals without intellectual disability to report poor or only fair health, and much less likely to describe their health as excellent. They indicate that they are more likely than others in the general population to live an inactive lifestyle and less likely to be physically fit (Campbell, 2001). As a result, people with intellectual disabilities are also more likely than others to be overweight (or in some cases underweight) and are at increased risk for illnesses and diseases associated with weight-related conditions. High rates of victimization also place both children and adults with intellectual disabilities in positions of health and mental health risk. Children with intellectual disabilities, for instance, are four times more likely to be abused than children without intellectual disabilities, while women with intellectual disabilities are 50% more likely to be sexually abused than women without intellectual disability (Horwitz et al., 2000; Sobsey & Doe, 1991).

In all cases, potential health complications associated with specific conditions deserve careful vigilance. For example, individuals with Down syndrome are more likely than other people to have congenital heart defects, thyroid disease, leukemia, and Alzheimer-like neurodegeneration. They are also at greater risk for weight and lifestyle-related problems such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes. Because of the high prevalence of associated conditions, Sullivan and colleagues (2006) have argued that patients with intellectual disabilities require more attention from health care providers than most other patients.

People with intellectual disabilities have associated health conditions that account for some premature mortality. But a related problem is that they also have less access to adequate health services. This means that the presence of intellectual disability decreases the likelihood that an individual will receive accessible information and opportunities important to leading a healthy lifestyle. It also means that when the individual is ill, he or she is less likely than members of the general population to receive treatment, and more likely to receive inadequate or inappropriate treatment, if treatment is provided at all. A report by Britain’s leading advocacy group for people with intellectual disabilities, Death by Indifference (Mencap, 2007), asserts that disparities in health status and health service are due to institutional discrimination. From the organization’s perspective, institutional discrimination occurs when people with intellectual disabilities are not valued in a manner equal to that of other citizens needing health services. This factor, along with failure to understand the needs of people with intellectual disabilities and to adapt service delivery to them means that their health needs are sometimes not met.

Landmark documents from Britain (Valuing People and Valuing People Now, Department of Health, 2001, 2009) and the United States (Closing the Gap, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2002), among others, agree that health services for people with intellectual disabilities have been inadequate, and they call on health care professionals to confront their own prejudices and address their own educational needs, where they exist, so that they are better prepared to provide services equal to those given to the general population. As well, a sizable body of literature supports the idea that people with intellectual disabilities have been and remain inadequately served by the health care system. In most cases, disparity in access to adequate health services does not represent a conscious decision but a long-established or entrenched way of practising. The following factors, separately and in combination, contribute to the comparatively poor health and generally shorter lifespans experienced by people with intellectual disabilities.

Lack of health care providers who are willing to provide or interested in providing care and treatment for individuals with intellectual disabilities. Most people with intellectual disabilities have always lived in their home communities, and de-institutionalization has repatriated the great majority of others who were previously institutionalized. However, some mainstream health care practitioners still don’t see people with intellectual disabilities as being their responsibility. Instead, people with intellectual disabilities are viewed as being the responsibility of a specialized system that deals specifically with this population. The result is that some people with intellectual disabilities are not able to have their health needs met (Mencap, 2004).

Absence of adequate preparation for health care providers. The World Health Survey of 51 countries (World Health Organization/World Bank Group, 2011) reported that people with disabilities were more than twice as likely as people without disabilities to describe health care provider skills that were inadequate to meet their needs. This survey also found that people with disabilities were three times as likely to be denied needed health care.

Surveys have found that few health care practitioners are educated about intellectual disabilities, and many admit that they have insufficient education to effectively meet the health needs of patients with intellectual disabilities (Mencap, 2004; NHS Scotland, 2004; Ouellette-Kuntz et al., 2004; Reichard & Turnbull III, 2004; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2002). In one survey of 215 general practitioners, for example, 75% indicated that they had no training related to treating people with intellectual disabilities (Mencap, 2004). The resulting lack of confidence and feelings of inadequacy have contributed to practitioners’ reluctance to treat and care for patients with intellectual disabilities, which is commonly reflected in the following ways:

- Uncertainty about how to interact with patients with intellectual disabilities

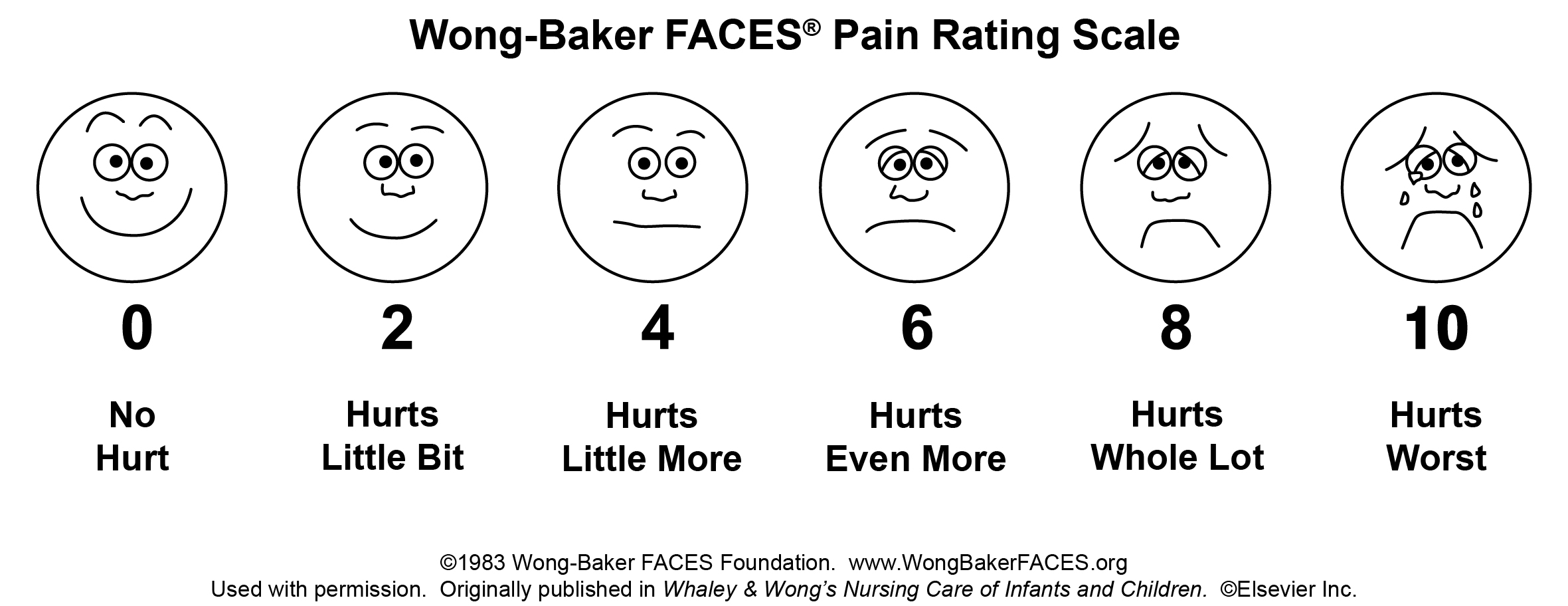

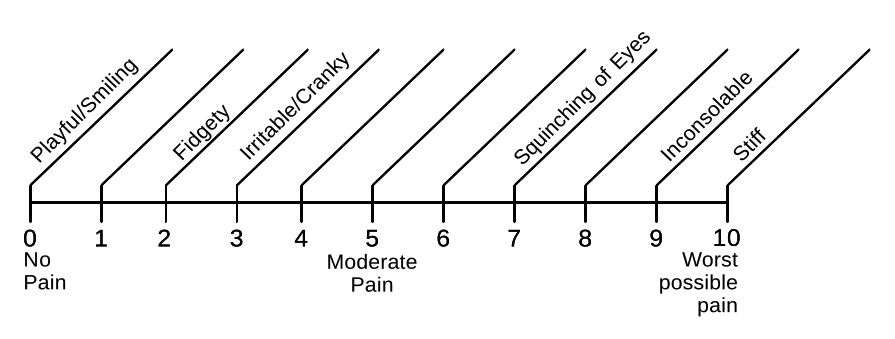

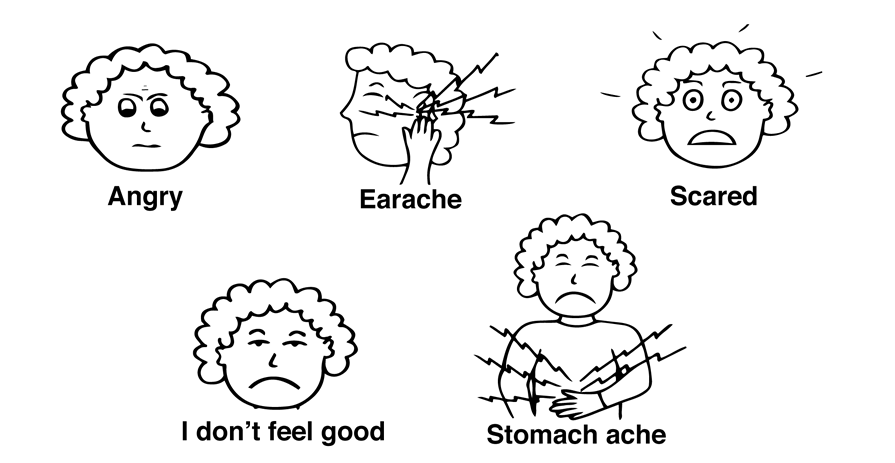

- No understanding of illness presentation by individuals with intellectual disabilities, particularly in the case of patients with severe disabilities and limited verbal skills (often experienced as inability to correctly interpret behavioural clues as indicators of illness-related or anxiety-related distress)

- Inadequate understanding of health problems and issues experienced by individuals with complex developmental disabilities and intellectual disability

- Inadequate understanding of methods to adapt to challenges in promoting mutual comfort and effective communication during examination and treatment processes

- Misconceptions about intellectual disabilities

- Uncomplimentary attitudes about people with intellectual disabilities

On the other hand, education has been shown to better prepare health care providers to treat and care for patients with intellectual disabilities. Education is effective in changing misconceptions, challenging and overturning uncomplimentary attitudes, and producing greater willingness to treat and care for patients with intellectual disabilities (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2002).

The nature of the health care system. Modest fee-for-service rates, along with significant capital expenditures, operational costs, and high patient volume, interfere with the ability of many primary health care providers to contribute the time needed to effectively assess and treat patients with intellectual disabilities. Depending on individual characteristics, patients with intellectual disabilities may require longer appointments or a series of shorter appointments. In some cases, extra orientation and follow-up time may be needed to promote patient comfort, familiarity with procedures, and general understanding (Reichard & Turnbull III, 2004; Royal College of Nursing, 2006). Unwillingness or inability to accommodate the longer appointments required by many patients with intellectual disabilities has an impact on the adequacy of health care provision and may discourage contact with health care providers entirely.

The general unfamiliarity of health care professionals with people with intellectual disabilities can also be problematic. Confusion about laws on consent and the rights of individual patients with intellectual disabilities, along with absent or inaccurate information about intellectual disabilities, can cause health care providers to make decisions based on faulty assumptions.

The nature of the intellectual disability service and support system. In its World Report on Disability, the World Health Organization/World Bank Group (2011) reported that many residential and home care workers are poorly trained and poorly paid. This is commonly the case for those who support people with intellectual disabilities as it is for those who work in the broader home care service industry. This means that, in many cases, salaried support providers have limited skills in recognizing and acting on health care problems (Australian Association of Developmental Disability Medicine Inc. and National and NSW Councils for Intellectual Disability, n.d.). In places where formalized education does exist, as across much of Canada, the sheer size of the demand for support providers, along with comparatively poor salaries, means that individuals without formal credentials regularly give direct support. For these individuals, support provision is often a brief stop before moving on to something else.

Because high support-staff turnover rates are common within most intellectual disability-related service systems (exceeding 100% per year in some cases), knowledge about and understanding of supported individuals is often compromised (Melrose et al., 2013; Royal College of Nursing, 2006). This means that individuals with intellectual disabilities may not have advocates or surrogates who are sufficiently familiar with their personalities, communication styles, idiosyncrasies, and physical health issues. This also has negative implications for the psychosocial health of individuals with intellectual disabilities, who have no control over the continuance of significant relationships in their lives.

The service and support system is shifting in emphasis from a medical model to a social or human rights model that gives attention to inclusion and participation, autonomy, and individual choice. This, however, may make it more difficult for some support providers to notice and respond to health matters (Royal College of Nursing, 2006). Support providers may also hold prejudices against the health care system, based on their familiarity with the troubled historical relationship between the health care system and people with intellectual disabilities. In one case, support providers in a community residence in the United States refused to give prescribed antidepressant medications to a person with intellectual disabilities, citing well-known concerns about the overuse of antipsychotic medications with the intellectual disability population. In this case, the distrust of the support providers, at least in part, may have unwittingly contributed to the person’s suicide some time later (Brown, 1990).

Poor socioeconomic conditions. Intellectual disability occurs across all socioeconomic sectors in all societies. Although intellectual disability “seems to know no boundaries, it is observed in disproportionately high numbers in the more vulnerable segments of the population such as the poor, the disenfranchised, and ethnic minorities” (Beirne-Smith, Ittenbach, & Patton, 2002, p. 208). This imbalance, however, appears to be the case only for people with intellectual disabilities who have IQs higher than 50; comparatively severe intellectual disabilities is evenly distributed among socioeconomic divisions (Department of Health, 2001).

While the reasons for the uneven distribution of mild intellectual disabilities are not entirely clear, individuals with an income below the poverty line are three times more likely to have intellectual disabilities than those who don’t experience poverty. Though people with intellectual disabilities (and people with disabilities, generally) are overrepresented in low-income and unemployed sectors, poverty in itself creates a web of conditions that dramatically increases the risk for developmental concerns and ill health (Drew & Hardman, 2004). For example, poverty means that food and adequate housing are less affordable, if affordable at all. Poor children are more likely to experience malnutrition and exposure to various environmental contaminants and toxic substances.

In general, disadvantaged social groups are more likely to be poor and at greater risk for illness and disability. In Canada, for instance, the poverty rate for young children who are Aboriginal, new immigrants, or members of a visible minority is about twice that of all children (Campaign 2000/2003). In the United States, the rate of poverty for people who identify as African-American is about three times that of people who are listed as non-Hispanic White (8% vs. 24.1%; U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2003).

While being poor or coming from a minority population increases exposure to conditions that are known to produce illness and disability, these circumstances also place individuals at the core of a complex interaction of factors that increase the risk of illness and disability. Vulnerable people have the additional risk of less access to essential health and social services as others (Beirne-Smith, Ittenbach, & Patton, 2002). It is a paradox that these essential health and social services seem to be least available to the people who most need them.

Dependency and limited communication skills. The dependence of people with intellectual disabilities on others can interfere with their ability to resolve health-related issues and problems. In many cases, primary support providers must be able to detect and report symptoms of illness that individuals with intellectual disabilities may not be able to communicate themselves (Horwitz et al., 2000; Nocon, 2006; Ouellette-Kuntz et al., 2004; Reichard & Turnbull III, 2004). Limited communication skills reduce the chances of identifying and reporting illness early (if reporting occurs at all), and often inhibit or prevent the first-hand descriptions of illness that health care providers commonly rely on for accurate diagnosis and treatment.

Individuals experiencing illness are inclined to automatically defer to others in perceived authority and the wish to please others, which can also interfere with accurate diagnosis and treatment of health problems. This inclination is characterized by the tendency to give the response that the ill person believes the health care provider is seeking, or the response that the ill person thinks is most likely to gain approval. In this context, health care and support providers need to be conscious of asking questions in an understandable manner and avoid leading questions that suggest a preferred answer. When the accuracy of an ill person’s response is in doubt, it can be helpful to pose the original question again in another form. If the question requires a yes or no response, asking the same question in its opposite form can help confirm the accuracy of the original reply (Royal College of Nursing, 2006).

Like many people, individuals with intellectual disabilities may be reluctant to seek medical care because the diagnostic process, imagined consequences, and anticipated procedures frighten them. This feeling can be compounded by concern about new and unfamiliar surroundings, and by apprehension about interacting with unfamiliar health care providers.

Factors Affecting Health Status

Factors Affecting Health Status

Key Points for Caregivers

People with intellectual disabilities have the right to be as healthy as anyone else. They also have the right to the same health care access and treatment as others within the general population. Examples of legislation that protect the equality rights of all persons with disability are section 15 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, the U.S. Americans with Disabilities Act, and Britain’s Disability Discrimination Act. In addition, the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities is a declaration of commitment to equality rights that has been ratified by 143 countries.

To promote health care access and adequate treatment, those who support and care for people with intellectual disabilities are encouraged to take responsibility for each of the following activities:

- Maintain ongoing records regarding health status, including changes in weight, eating and elimination patterns, sleeping patterns, mood, behaviour, illnesses, medications (including effects and side effects), communication methods, issues related to specific conditions and situations, and any concerns that develop, along with events that occurred prior to the development of those concerns.

- Act as a resource for health care professionals; for example, ongoing health status records can be shared during appointments. Formal assessment tools such as the Comprehensive Health Assessment Program (CHAP) can be used by the health professional and support provider to develop a complete health history (Lennox et al., 2007). The CHAP is available as a 21-page booklet with two parts. The first part is completed by the support provider in advance of the appointment and provides a health history along with a description of the issue that prompted the appointment with the health professional. The second part is completed by a general practitioner and involves a review of the health history and then a targeted examination of the individual. At the end, a health action plan is developed. A feature of the CHAP is that it prompts the doctor to be aware of health conditions that are commonly missed or poorly managed, as well as health conditions that occur to individuals with specific syndromes. The CHAP booklet can be downloaded from certain CHAP-related websites on request by representatives of support agencies.

- Arrange appointments with health care providers that are long enough to accommodate the person’s needs. This may include arranging health care appointments during clinic times that are comparatively quiet. In some cases, a preliminary visit or visits may need to be scheduled for the support provider to discuss the impending health-related appointment with a cooperating health care provider. Information important to a successful appointment can be discussed, such as the client’s method of communication (verbal or by signing, computer assistance, pictures, symbols, or other means). Other impactful issues can be discussed, such as the need to provide health-related information in small amounts and to allow sufficient time for information processing and understanding. In addition, the support provider should obtain a practical understanding of expectations and procedures that the client will encounter so that the support provider can adequately prepare the individual for the appointment.

- Explain and/or demonstrate behaviours that will be expected or procedures that will be performed when at the health care provider’s, to promote understanding and reduce anxiety. This should be done in advance of an appointment. For some individuals, this may require a desensitization process over a period of days, weeks, or months. In this case, a task analysis should be developed that breaks down an expectation or procedure into its component parts, so that each part can be taught in succession until the complete expectation or procedure is understood and tolerated (see Table 4.1).

Table 4.1 Example of task analysis

| ACTIVITY: GETTING A FLU SHOT Name of Trainer: |

STEPS | STEP COMPLETED | DATE COMPLETED | COMMENTS | TRAINER INITIALS |

| 1 | The nurse will ask you to roll up your sleeve. | YES | NO | | | |

| 2 | The nurse will clean a small part of your skin near the top of your arm. | YES | NO | | | |

| 3 | A needle will be put in your arm and then removed. It may hurt a bit. | YES | NO | | | |

| 4 | A small band-aid will be put over the spot on your arm where the needle was given. | YES | NO | | | |

| 5 | You can now roll down your sleeve. | YES | NO | | | |

Notes: - Pictures can be used at each step of the procedure along with verbal instructions.

- For individuals with severe disability, the instructor will need to demonstrate each step with the individual while using a model for the actual needle.

- A reinforcer may need to be given for individuals with severe disability and anxiety.

|

Constipation

By definition, constipation occurs when a person has two or fewer bowel movements in a week. This is commonly accompanied by straining during bowel movements or by simply having difficulty with bowel movements (for example, trying for 10 minutes without success). The inability to completely evacuate the bowels and producing hard or pencil-thin stools are also characteristic of constipation. Support providers should view a swollen abdomen, abdominal pain, and vomiting as possible indicators of constipation.

Though at one point or another constipation affects nearly everyone, chronic constipation occurs more commonly in people with intellectual disabilities. Morad and colleagues (2007) found that 8% of more than 2,000 individuals in Israeli residential facilities were experiencing constipation at the time of their survey, although only about 2% of the general population is thought to have constipation at any given time.

Constipation is more likely to affect those with severe or profound disabilities, those with mobility restrictions, or those who are otherwise inactive. In one study, almost 70% of institutionalized persons with severe or profound intellectual disabilities were experiencing constipation at the time of the study (Bohmer et al., 2001). Neurological conditions such as cerebral palsy place individuals at greater risk for constipation. It is also more likely to affect those with inadequate hydration and limited food choices (inadequate dietary fibre and excessive amounts of dairy products), and those taking long-term medications that produce constipation as an incidental consequence. Examples of these medications are anticonvulsants, benzodiazepines (minor tranquilizers), and antacids containing calcium. In some cases, overreliance on laxatives contributes to constipation becoming chronic. When symptoms are unrecognized in people with intellectual disabilities, constipation can pose a serious threat to health, including the possibility of death (Royal College of Nursing, 2006).

Common Health Challenges: Constipation

Common Health Challenges: Constipation

Key Points for Caregivers

- Prepare or promote the preparation of well-balanced meals that include adequate sources of fibre such as fruits, vegetables, and whole grain breads.

- Encourage adequate fluid intake. Eight glasses of water or other fluids each day can be considered adequate, unless an individual has fluid intake restrictions or other requirements. Caffeine-containing drinks have a dehydrating effect and milk or dairy-based drinks may be constipating for some people.

- Promote or provide regular daily exercise. For individuals in wheelchairs, occasional side-to-side movement, if possible, or exercise while seated in the chair may be helpful. A physiotherapist may be able to recommend exercises and activities.

- Encourage supported individuals to move their bowels when they feel the urge.

Seek medical assistance if:

- Constipation is experienced for the first time or there has been a change in bowel routine

- Constipation does not respond to natural remedies such as increased dietary fibre or fluid intake, or to replacing sedentary activity with regular exercise such as walking or swimming

- Blood is evident in stool or during bowel movements, or rectally at any other time

- Unplanned weight loss occurs

- Pain occurs with bowel movements, or abdominal pain or cramps occur

- Nausea or vomiting occur

- Constipation lasts for more than two weeks

Epilepsy

Epilepsy is a common condition in people with intellectual disabilities, with prevalence increasing with the severity of the disabilities. In situations where intellectual disabilities and cerebral palsy coexist, and for individuals with severe intellectual disability, the prevalence of epilepsy is about 50%. The cause is often complex, and in 50% to 60% of cases the cause is unknown. The same cause may produce both intellectual disability and epilepsy or, in some cases, epilepsy itself may be responsible for the intellectual disability. In any case, epilepsy contributes to the morbidity and mortality profiles of many people with intellectual disabilities and represents a condition requiring careful observation (Royal College of Nursing, 2006; Santos-Teachout et al., 2007).

By definition, epilepsy is characterized by sudden, brief changes in the brain’s electrical activity. It is a symptom of a neurological disorder and is expressed in the form of seizures (Epilepsy Canada, n.d.). Seizures can be generalized or partial, depending on the extent of brain involvement. If there is extensive activity affecting the entire brain, then seizures are generalized. If the activity is localized in a specific area of the brain, the seizure is considered partial. A single seizure does not constitute epilepsy, nor do seizures associated with conditions that may cause event-specific seizure activity, such as illness with an accompanying fever in young children (febrile seizures). An actual diagnosis of epilepsy depends on an observable pattern of seizure activity along with confirming results from specific diagnostic testing.

Events that may trigger seizures (Epilepsy Canada, n.d.) include:

- Stress

- Poor nutrition

- Missed medication

- Flickering lights

- Skipping meals

- Illness, fever, and allergies

- Lack of sleep

- Emotions such as anger, worry, and fear

- Heat or humidity

Whether generalized or partial, epileptic seizures can take a number of different forms. The most common form or type of epileptic seizure is the complex partial seizure, which accounts for 40% of all seizures. These seizures are often preceded by an aura, which is a strange sensation such as an odd smell, strange taste, tingling sensation, unusual sound, or a sense of uneasiness or dread. An aura is actually a simple partial seizure, and may be the only form of an individual’s seizure activity; this is the case in 20% of seizures. In the case of complex partial seizures, however, an aura may signal that a seizure is about to take place. An individual who then experiences a complex partial seizure may appear dazed and confused and may engage in random walking, mumbling, head turning, and pulling at his or her clothes. There is a change in the individual’s level of consciousness (the individual is not fully conscious, nor is he or she unconscious), with the seizure itself lasting from 30 seconds to three minutes.

Tonic–clonic seizures (previously called grand mal seizures) are generalized, and are the kind of seizure that commonly comes to mind when epilepsy is mentioned, though they only account for 20% of all seizures. The characteristic pattern of tonic–clonic seizures may or may not include an aura. When an aura is present, it provides a warning that may permit the individual time to lie down on the floor or may allow someone nearby to assist the individual to the floor before he or she becomes unconscious and otherwise falls. The aura may be accompanied by a cry that also serves a warning that a seizure is about to take place.

Normally, a tonic–clonic seizure lasts from one to a few minutes and has two distinct phases. The tonic phase is characterized by stiffening of the body and is followed by the clonic phase, characterized by energy release in the form of rhythmic jerking of the extremities, otherwise called a convulsion. In the tonic phase, breathing may appear to be suspended (lips may turn blue). During the seizure, the individual may drool and may lose bladder and/or bowel control. After the clonic phase and then recovery, breathing may appear to be stertorous or audible, much like snoring. While the individual may bite his or her tongue, at no time should a support provider try to insert anything into the individual’s mouth. During the tonic phase the jaw is tightly clenched, and during the clonic phase teeth commonly chatter. Attempting to insert an object such as a spoon into the individual’s mouth to compress the tongue at any point during a seizure may cause injury. Contrary to the once popular myth, people cannot swallow their tongue. Once a seizure has run its course, the individual is typically confused, tired, and may have a headache. He or she will have no memory of the seizure and will require time to rest.

When assisting individuals experiencing tonic–clonic seizures:

- Stay calm.

- If possible, assist the person to the ground.

- Protect the person from injury by removing nearby obstacles that he or she may bang up against.

- Do not restrain the person.

- Do not insert anything into the person’s mouth.

- Time the duration of the seizure.

- Call for medical assistance if the seizure lasts for five minutes or more.

- Once the seizure is over, place the person in the recovery position (on his or her left side) and allow him or her to rest, checking back periodically.

- Reassure and reorient the person when he or she has recovered.

Absence seizures (previously called petit mal seizures) are very brief, lasting for a matter of seconds. They occur more often to children than to adults, and when they occur, the individual gives the impression of daydreaming, momentary inattention, or staring. Because of their brief nature, others who may be with individuals experiencing these seizures may not notice the seizure activity.

Other types of epileptic seizures are myoclonic, involving a single or repetitive jerking of muscles without a loss of consciousness, and atonic, also called akinetic or drop seizures. In atonic seizures, loss of muscle tonicity occurs and the individual is unable to sit or stand; if standing, the individual will fall to the ground without a loss of consciousness. Like tonic–clonic seizures, atonic seizures create a risk for injury.

Seizures that last for more than five minutes tend not to resolve without medical intervention. Therefore, seizures that last for five minutes or longer, or two or more seizures that occur in succession without intervening periods of recovery or return to normal functioning, should be considered a medical emergency. This condition is known as status epilepticus (Brophy et al., 2012). Status epilepticus can occur in cases of non-convulsive as well as convulsive epilepsy. In all such cases, an ambulance should be called.

Common Health Challenges: Epilepsy

Common Health Challenges: Epilepsy

Key Points for Caregivers

- Be conscious of situations and conditions that are likely to trigger seizures for supported individuals. Avoid or reduce exposure to triggers whenever possible.

- Provide appropriate assistance to the individual if a seizure does occur.

- After a seizure, record the conditions under which the seizure occurred, along with a description of the seizure activity. Describe how long the seizure lasted and emergency measures if needed. Describe any events that accompanied the seizure, such as loss of bladder control or injury. Describe the nature of the recovery after the seizure.

Respiratory Disease

Though the vast majority of individuals with intellectual disabilities live in community settings, existing institutions characteristically house a disproportionate number of individuals with severe and profound intellectual disabilities. Difficulties with movement, independent mobility, and swallowing are especially high within this population. As a result, and because of the risks inherent in community living, institutionalized individuals (and individuals in other community situations) are particularly susceptible to respiratory infections through transmission of infectious agents, aspiration (breathing food or liquid into the lungs), and reflux (see discussion on gastrointestinal problems). Almost half the deaths that occur in institutions are attributed to the respiratory illnesses pneumonia and influenza.

Individuals with Down syndrome are also at particular risk for respiratory infections. These individuals tend to breathe through the mouth and have physical malformations that can interfere with sinus drainage, and a poor immune system that makes them susceptible to infections (Horwitz et al., 2000; Royal College of Nursing, 2006).

Cancer

The rate of gastrointestinal cancer in individuals with intellectual disabilities is about twice the rate as that observed in the general population. This may be due to gastrointestinal reflux (see discussion on gastrointestinal problems) and chronic constipation that are comparatively common in individuals with severe and complex disabilities living in community settings. Individuals with Down syndrome are at risk for a particular form of cancer called lymphoblastic leukemia (Horwitz et al., 2000).

Cardiovascular Disease

Cardiovascular disease accounts for as much as 50% of deaths among people with intellectual disabilities, depending on the population reviewed. Because of lifestyle factors that more closely resemble those of the general population, individuals with mild intellectual disabilities (about 85% of people with intellectual disabilities) are more vulnerable than individuals with more severe disabilities.

Congenital heart defects affect 30% to 60% of children with Down syndrome, regardless of severity. Congenital heart defects are also common in children with Williams syndrome. With advances in medical technology, however, survival rates have improved dramatically over the years. Vigilance remains important for at-risk populations, with electrocardiogram and echocardiogram screenings recommended for infants with Williams or Down syndrome (Horwitz et al., 2000).

Diabetes

The likelihood of developing diabetes appears to be greater for people with intellectual disabilities than for the general population. This seems to be the case even more for people with Down syndrome, who appear to have a greater likelihood of developing the disease at an earlier age (Horwitz et al., 2000; Royal College of Nursing, 2006).

Gastrointestinal Problems

Comparatively high rates of helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection are found in people with intellectual disabilities who are in community living situations or who attend day centres or vocational workshops. H. pylori is a bacterium that usually infects the stomach and, along with reflux and chronic constipation, is viewed as a predisposing factor for the greater occurrence of gastric cancer observed in people with intellectual disabilities (Royal College of Nursing, 2006).

Gastroesophageal reflux disease and reflux esophagitis occur frequently in individuals with severe or profound intellectual disabilities. These are chronic conditions caused by stomach acid entering the esophagus. Their prevalence in people living in institutions is high. Individuals with Fragile X syndrome also have particular vulnerability, as do individuals with scoliosis, cerebral palsy, and those taking anticonvulsant medications or other benzodiazepines. Though easily treated, gastroesophageal reflux disease is often unnoticed in individuals with intellectual disabilities, which may be why they have a higher rate of esophageal and gastrointestinal cancer. Vomiting (along with blood in the vomit), effortless regurgitation of meals after eating, and depressive symptoms, should raise clinical suspicions (Santos-Teachout et al., 2007).

Sensory Impairments

The available data show that as many as 72% of all children with intellectual disability have ophthalmological problems (compared with 25% in the general population). Common vision impairments are refractive errors, strabismus (the muscles of the eyes not well coordinated and the eyes not lining up in the same direction), cataracts (clouding of the lens of the eye), keratoconus (thinning cornea and bulging outward in a cone shape, causing blurred vision), nystagmus (repetitive, uncontrolled movements of the eye that can result in poor vision), and poor visual acuity (Royal College of Nursing, 2006). Individuals with severe intellectual disabilities are more likely to have visual impairments than individuals with mild intellectual disabilities. They are also more likely to have hearing problems, with about 40% of individuals with severe disabilities believed to have hearing impairments (Santos-Teachout et al., 2007).

People with intellectual disabilities tend to experience vision and hearing deterioration earlier than the general people. In addition, some causes of intellectual disabilities, or their co-occurring conditions, also produce sensory impairments. Cerebral palsy, Fragile X syndrome, and fetal rubella syndrome are associated with such impairments. Adults with Down syndrome who are over the age of 30 are predisposed to develop premature age-related cataracts, refractive errors, and degenerative corneal problems. They are also at risk for early age-related hearing loss. On the whole, deafness is comparatively common in people with intellectual disabilities, but it is frequently unrecognized or poorly managed (Horwitz et al., 2000).

Obesity

Although obesity, generally, is on the rise in North America, obesity levels in people with intellectual disabilities remain higher than in the general population (Horwitz et al., 2000; Rimmer & Yamaki, 2006). Adults with mild intellectual disabilities, especially women, are most vulnerable. Individuals with comparatively severe intellectual disabilities are less likely to be overweight or obese, likely because of the greater menu control maintained by support providers. Therefore, risk of obesity decreases as the severity of disability increases (Stancliffe et al., 2011).

Living situations and the cause of the disability are also factors and have a noticeable impact on obesity prevalence. Individuals with intellectual disabilities who live at home or on their own, for instance, have a higher rate of obesity than those in community living situations. Individuals who live their own are more likely to have unbalanced meals and rely on convenience foods (Horwitz et al., 2000; Royal College of Nursing, 2006).

Some genetic conditions or chromosomal irregularities that cause intellectual disability are associated with weight-related problems. For example, Down syndrome or Prader-Willi syndrome are correlated with weight gain or obesity (a primary feature of Prader-Willi syndrome is compulsive overeating). Other factors that create risk for obesity and its inherent dangers are:

- The tendency to be physically inactive (In a survey of 1,500 people with intellectual disability in 14 European countries, more than 50% of individuals reported sedentary leisure time activities such as TV watching or reading [Walsh, Kerr, & van Schrojenstein Lantman-Devalk, 2003].)

- Dependence on others to create opportunities for physical activity

- Lack of access to or difficulty understanding health promotion materials and campaigns that encourage healthy lifestyles

- Greater likelihood (compared with the general population) of being on medications such as anticonvulsants or antipsychotics that have weight gain as a side effect (Horwitz et al., 2000; van Schrojenstein Lantman-De Valk, Metsemakers, Haveman, & Crebolder, 2000)

Some individuals with intellectual disabilities are at comparatively greater risk for being underweight. This is the case for individuals with metabolic disorders such as phenylketonuria (PKU), in which certain nutrients cannot be effectively broken down and used by the body, and for individuals with swallowing or feeding problems that can be attributed to severe neurological damage (Royal College of Nursing, 2006). An additional concern for individuals with swallowing or feeding problems is the potential for choking and for aspiration. In this case, the principal caution is that those who assist with feeding must understand proper techniques to lessen the risk for choking and aspiration.

Where weight-related or swallowing/feeding-related concerns exist, appropriate health care providers should be consulted. For instance, a nutritionist can develop a weight management program for individuals whose weight presents a health concern. Similarly, an occupational therapist can provide instruction about how to correctly assist individuals who have swallowing or feeding challenges, as may be the case with individuals who have severe forms of cerebral palsy. For example, the therapist will be able to demonstrate alternative techniques to the dangerous practice of “bird feeding” (feeding an individual with his or her neck extended and increasing the risk of aspiration of food or liquid into the lungs).

Medication Use

In its survey of 14 European countries, the Pomona Project found that 65% of people with intellectual disabilities used one or more medications (Walsh et al., 2003). About 50% used nervous-system-related medications, principally anti-epileptics, antipsychotics, and antidepressants. High rates of polypharmacy, or use of multiple medications, mean that individuals with intellectual disabilities are more susceptible to drug interactions than is the general population. Such interactions may produce, among other possibilities, sedation, confusion, constipation, balance difficulties and falls, incontinence, weight gain, impairments in epilepsy management, metabolic effects, and movement-related disorders (Ouellette-Kuntz et al., 2004). Therefore, support providers and health care providers must understand the effects and side effects of medications used by clients and patients with intellectual disabilities, and the extent to which those clients and patients experience them.

The use of antipsychotic medications with people with intellectual disabilities has been controversial and is often high in long-stay institutions. Emerson and Baines (2010) report use by almost 45% of institutionalized people in the United Kingdom. Use diminishes to 20% to 30% in community-based residences, and to around 10% in family homes. Individuals who are most likely to receive antipsychotic medications are those who reside in congregate living situations, are mobile, and are overweight. Antipsychotics cause weight gain, however, so it is unclear whether weight is a factor that influences prescription or a feature of prescription usage. Antipsychotic medication use also appears more prevalent in situations where nurses are the main support providers.

Antipsychotic medications are meant for a specific purpose: to treat individuals who are or at risk of psychosis, like that experienced by people who live with schizophrenia. For the most part, however, antipsychotics are prescribed as a mechanism to manage challenging behaviour in people with intellectual disabilities. This has occurred and continues to occur in some circumstances “despite no evidence for their effectiveness in treating challenging behaviours and considerable evidence of harmful side effects” (Emerson & Baines, 2010, p. 10).

The challenge for support providers is to apply appropriate assessment approaches to better understand and respond to challenging behaviours when they exist. This may include consulting behaviour specialists. Support providers must keep in mind that behaviour occurs in a context that includes both an individual’s internal experience and external or environmental conditions. This means that components of the physical and social environments also need to be considered when trying to understand why challenging behaviours occur.

Mistreatment

There is widespread agreement that the prevalence of abuse in children and adults with intellectual disabilities is greater than in the general population. Unfortunately, abuse often comes from the hands of those who are assigned to provide care, support, and protection.

Though abuse of individuals with intellectual disabilities is no longer an accepted standard (as it was through much of history), it nonetheless continues to occupy a place in the dark corners of the disability world. In one study, Waldman, Swerdloff, & Perlman (1999) found that children who are abused are four times more likely to have intellectual disabilities than non-abused children. In another study, Verdugo, Bermejo & Fuentes (1995) found that 11.5% of children with intellectual disabilities had some evidence of mistreatment by age 19, compared with 1.5% of children without intellectual disabilities. In a more general study, Crosse, Kayey, & Ratnofsky (1993) found that children with disabilities are almost two times more likely to be sexually abused than children without disabilities. Though mistreatment is likely the result of a convergence of multiple factors, factors that appear to place individuals with intellectual disability at greater risk are:

- The view that people with intellectual disabilities are “less human” and therefore less valuable (or simply that they are lesser valued human beings)

- Physical and social isolation/segregation or marginalization, and the societal perception of differentness

- Lack of personal empowerment or ability/opportunity to influence others or circumstances

- Dependence on caregivers and support providers

- Learned compliance—people with intellectual disability are characteristically expected to do as they are told, to acquiesce to the requests, demands, and commands of others

- Physical defencelessness—people with intellectual disabilities who are dependent on others often have no recourse to defend themselves, to run, or to make other choices that will reduce the likelihood of mistreatment

- Limited opportunities to develop social skills and resources needed to prevent or escape mistreatment

- Unwillingness by others to believe information from the mistreated person with disability or unwillingness to act on news of mistreatment—cultures of silence and inaction can develop among support and health care providers that function to tacitly approve and maintain mistreatment of vulnerable persons

- Limited communication skills—the individual with intellectual disabilities may not be able to speak or may have very limited word skills

- The inability of the individual with intellectual disabilities to differentiate between normal and unacceptable behaviour by others—individuals with intellectual disabilities are at risk for exploitation and sexual abuse because of limited or absent sex education, for example

- Limited cognitive abilities, increasing risk for mistreatment by people who misinterpret lack of understanding for non-compliance, and by people who are impatient or who see little personal risk in mistreating people who are at a cognitive disadvantage

- Behavioural challenges or overly compliant behaviour by the person with disability

- Stressful working or living conditions with limited resources and supports—for example, health care professionals or support providers responsible for supervising an unreasonably large number of individuals, workers not sufficiently prepared or supported to help individuals with challenges, or a socially isolated parent who is unable to cope with the 24-hour requirements of his or her son or daughter

- Absence of exemplary role models—when capable and caring colleagues, managers, family members, or friends are absent, inappropriate behavioural responses are more likely to be accepted and normalized within a specific environment

- Insufficient education and lack of supervised practice and feedback

- Lack of effective and enforced policies and procedures. Abusive behaviour is more likely to occur in workplace environments where there are no formalized expectations, requirements, or guidelines that support appropriate behaviour and deter inappropriate or abusive behaviour. Abusive behaviour is also more likely to occur in environments with appropriate policies and procedures when compliance with those policies and procedures is not effectively monitored and enforced (Manitoba Family Services and Housing, 2000).

Common Health Challenges: Mistreatment

Common Health Challenges: Mistreatment

Key Points for Caregivers

The foundation to providing appropriate support is respect for the right of individuals with intellectual disability to make informed choices and decisions about their own lives. Informed choices and decisions mean that people make their decisions based on a full and adequate understanding of all available options and their possible consequences. For supported persons with intellectual disability, it also means that they are able to discuss choices with people who are important to the decision and who genuinely have the best interests of the supported person in mind. When more severe disability exists, others must make decisions based on how they understand the supported person’s wishes and values, still in the genuine best interests of that person.

Down Syndrome

Down syndrome occurs because of a chromosomal irregularity in human chromosome 21 (chromosomes contain genes). In the vast majority of cases, Down syndrome occurs spontaneously, rather than by inheritance. Overall, the incidence of Down syndrome is about one in every 700 to 1,000 live births, with the rate increasing to about one in 35 by the time the mother reaches age 45. Because most children are born to younger women, however, 80% of all Down syndrome children are born to women below the age of 35. In about 5% of cases, Down syndrome originates in the father, with paternal age past 50 to 55 believed to be a factor.

Although the reasons are not fully understood, people with Down syndrome experience accelerated aging (National Down Syndrome Society, 2012). It seems likely, however, that accelerated aging is largely due to genes on chromosome 21 that are related to the aging process. According to Moran and colleagues (2013), “the experience of accelerated aging can be seen medically, physically and functionally” (p. 4). Family members and support providers often report that individuals with Down syndrome just seem to slow down in their late 40s and 50s. Support workers should be conscious of and prepared for aging-related issues that commonly affect individuals with Down syndrome before most other people. One major aging-related issue is the potential development of early onset Alzheimer disease. Like the aging process, this disease has a gene located on chromosome 21, causing individuals with Down syndrome to be susceptible to the disease.

Whether age-related or otherwise, certain health conditions are especially common among individuals with Down syndrome. The following deserve the attention of support providers and health care professionals:

- Atlantoaxial instability (AI). AI occurs in 10% to 40% of individuals with Down syndrome and involves a looseness of movement at the point where the first and second cervical vertebrae meet. This creates risk for spinal cord injury. Some experts believe that this risk necessitates curtailment of contact sports for individuals with AI. Screening for non-symptomatic AI is an important consideration for health care professionals.

- Congenital heart defects. While only 0.8% of children in the general population have congenital heart defects, 30% to 60% of children with Down syndrome are born with heart defects (Forster-Gibson & Berg, 2011).

- Thyroid disease. Individuals with Down syndrome have a greater prevalence of thyroid disorders and are more likely to contract thyroid disorders at an earlier age than the general population, with 15% to 50% being hypothyroid (Forster-Gibson & Berg, 2011).

- Osteoporosis. The prevalence of osteoporosis, or brittle bones, in the population of individuals with Down syndrome is uncommonly high. In addition to Down syndrome itself, accompanying features (where they occur) such as small body size, delayed puberty, early onset menopause, and hypogonadism (undersized testes) are contributing factors in the development of osteoporosis.

- Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer disease or Alzheimer-like neuropathology has a sweeping effect on the Down syndrome population, with as many as 50% of individuals affected by the age of 60. As mentioned, a genetic marker for Alzheimer disease is found on chromosome 21, meaning that people with Down syndrome are predisposed to Alzheimer disease.

- Leukemia. Childhood leukemia affects about 1% of individuals with Down syndrome. The risk for leukemia is 15 to 20 times greater than for individuals in the general population.

- Dental problems. Children and adults with Down syndrome commonly experience a variety of dental problems: delayed eruption of teeth, atypical sequence of eruption, missing teeth, enamel deficiencies, bruxism (teeth grinding), and periodontal (gum) disease. This suggests the importance of professional dental and periodontal care.

- Vision problems. Refractive errors are prevalent in individuals with Down syndrome, as are strabismus and nystagmus. Regular vision screening and optometric/ophthalmologic care is indicated.

- Other health problems. Drainage problems of the Eustachian tube (the tube that connects the middle ear to the back of the nose) and sinuses, scoliosis (curvature of the spine), gastroesophageal reflux, and seizure disorders are overrepresented in individuals with Down syndrome (Horwitz et al., 2000; Moran et al., 2013).

While Down syndrome is commonly accompanied by a variety of challenging medical complications, the advent of antibiotics and advances in medical procedures mean that many physical problems can be corrected or effectively treated. Because of these advances, the life expectancy of individuals with Down syndrome has improved dramatically.

Older People with Intellectual Disabilities

Like everyone else, people with intellectual disabilities experience health problems that are related to aging. However, older people with intellectual disabilities have higher rates of respiratory disorders, arthritis, hypertension, urinary incontinence, immobility, hearing impairment, and cerebrovascular accidents (strokes). Though the signs and symptoms of dementia are the same as those experienced by people without intellectual disabilities, dementia tends to be recognized later if it occurs. This may be due to support providers and health professionals confusing signs and symptoms of dementia with intellectual disabilities. It may also be due to the capacity of highly structured and routine environments, like those in community living situations, to mask emerging difficulties.

Note: Dementia is an umbrella term used to represent a cluster of symptoms that can be due to a variety of brain disorders (see Chapter 3). The symptoms include loss of memory, judgment, and reasoning, as well as changes in mood and behaviour. Functioning across everyday activities is impaired. It is important however, that support providers and health care professionals are aware that other conditions can produce symptoms similar to dementia. These can include depression, thyroid disease, infections, and drug interactions (Alzheimer Society of Canada, 2011). All of these need to be considered by health care professionals when there is concern about dementia or dementia-like features.

It is important for support providers to work with family members and to keep them or appointed guardians informed (for example, a family member who has been given substitute decision-maker status for an adult brother or sister.) In addition to simply being good, respectful practice, it may be a legal requirement to discuss health issues, plans, and potential actions with loved ones, and obtain consent for particular procedures.

With that understanding, support providers can have an impact on maintaining and improving health status by:

- Arranging health care screening for potential health problems, and particularly for health problems that occur more often in people with intellectual disabilities (for example, vision and hearing screens, as well as screens that are commonly recommended for all people at particular ages)

- Preventing or limiting the spread of infections by regularly and strategically washing their hands and sneezing into their sleeve (support providers should stay away from the workplace if they are ill)

- Using proper feeding and drinking techniques when assisting individuals with severe neuromuscular impairment and dependency needs, to decrease the risk of aspiration and aspiration pneumonia

- Promoting fitness and a heart-healthy lifestyle with attention given to exercise/activity and nutrition (with the guidance of appropriate health care and fitness professionals, and with attention to limitations imposed by some conditions)

- Knowing about and attending to the special dietary needs of individuals with disorders that require dietary modifications (such as phenylketonuria), with the guidance of appropriate health care professionals

- Ensuring that immunizations and immunization records are up-to-date

- Enabling access to the same health promotion information as other members of the general population through

- Modifying health promotion information as needed to promote understanding, with the assistance of public health professionals

- Providing opportunities to practice a healthy lifestyle

- Knowing, monitoring, recording, and reporting effects and side effect of medications; if giving medications is a recognized responsibility, giving them in the prescribed manner and in a safe and reliable way that conforms to best practice policies and procedures; arranging for regular medication reviews

- Recognizing that all behaviour is communication and that behaviour can communicate meaningful information about an individual’s health, which is particularly important when working with individuals with severe disabilities and others who do not speak, or who have limited speech (for example, self-injurious behaviour such as wrist biting or head banging is commonly associated with pain in people with severe disabilities, when it has not occurred before)

- Following or helping to improve existing policies and procedures, and obeying legal obligations related to the treatment of people with intellectual disabilities

- Participating in ongoing education programs that teach how to work with people with challenging behaviours (when they exist) in an effective manner, with attention to respect and dignity

The World Health Organization (2000) has stated that people with intellectual disabilities and their support providers need appropriate and ongoing education about healthy living practices. This information has commonly been inaccessible to many people with intellectual disabilities because of their dependency on others, and because of limited ability to understand, integrate, and independently act on healthy lifestyle information.

Gaining the attention of people with intellectual disabilities and their support providers is a central health promotion strategy. According to the U.S. Surgeon General, this means that healthy lifestyle information needs to be accessible, discussed, practised, and reinforced in the places where people with intellectual disabilities live, work, learn, and socialize (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2002). Toward that end, health promotion planning requires the conscious, deliberate inclusion or targeting of people with intellectual disabilities and the development of strategies that better promote understanding and intended action by people with intellectual disabilities and their support providers. The World Health Organization suggests adapting existing self-care and wellness programs to fit the needs of individuals with intellectual disabilities. Depending on specific needs, this may mean using assistive technology and different forms of media to imbed learning and reinforce healthy behaviours. It may also mean using a no-fail approach that includes reducing complex information into its more easily understood component parts and teaching in an incremental way until desired learning is established.

Health Promotion

Health Promotion

Key Points for Caregivers

Men and women with intellectual disabilities often lack the skill and opportunities to independently practise healthy living. Support providers and health care professionals are important to maintaining and improving health of people with intellectual disabilities through healthy living practices. This means that it is important for support providers and health care professionals to locate or develop best practice health promotion programs and then apply those programs. This gives people with intellectual disabilities the same opportunities to live healthy lives as other citizens.

In this chapter we have discussed the disparity in health status and lifespan between people with intellectual disabilities and the general population. For a small proportion of individuals with intellectual disabilities, health problems and reduced lifespan can be attributed to conditions associated with specific disorders, which can co-occur with or cause intellectual disabilities. For the most part, however, disparity in health status and reduced lifespan can be attributed to external factors that limit access to health care, or health care that is inappropriate or not equal to that received by most of the general population.

After the discussion of external factors affecting health status, we presented a discussion of issues and health problems that are particularly common to persons with intellectual disabilities. This included a discussion of the substantial vulnerability to mistreatment that many people with intellectual disabilities experience, and a specific discussion of Down syndrome and other health problems that occur more frequently. Accelerated aging was said to affect people with Down syndrome, but the entire population of persons with intellectual disabilities was also described as experiencing higher rates of many aging-related disorders and limitations.

Because of the high proportion of people with intellectual disabilities who require medications, and often multiple medications (polypharmacy), we have stressed the importance of safely providing and then monitoring the impact of medication use. The roles and responsibilities of support and health care providers received attention throughout the chapter, with the understanding that both groups are important to maintaining or improving the health of individuals with intellectual disability. Health promotion has been discussed as a particular strategy for maintaining and improving health that until now has largely been inaccessible to people with intellectual disabilities.

Chapter Audio for Print

This chapter contains a number of short audio clips. If you are reading this in print, you can access the audio clips in this chapter by scanning this QR code with your mobile device. Alternatively, you can visit the book website at opentextbc.ca/caregivers and listen to all the audio clips.

This chapter contains a number of short audio clips. If you are reading this in print, you can access the audio clips in this chapter by scanning this QR code with your mobile device. Alternatively, you can visit the book website at opentextbc.ca/caregivers and listen to all the audio clips.

Alzheimer Society of Canada (2011). What is dementia? [Fact sheet]. Toronto ON. Retrieved from http://www.alzheimer.ca/en/About-dementia/Dementias/What-is-dementia

Australian Association of Developmental Disability Medicine Inc. & National and NSW Councils for Intellectual Disability, (n.d.). Submission to the National health and hospitals reform commission. Retrieved from http://www.health.gov.au/internet/nhhrc/publishing.nsf/Content/450/$FILE/450%20%20National%20and%20NSW%20Councils%20for%20Intellectual%20Disability.pdf

Balogh,R., Ouellette-Kuntz, H., Bourne,L., Lunsky,Y., & Colantonio, A. (2008). Organising health care services for persons with an intellectual disability. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2008(4). doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007492

Beirne-Smith, M., Ittenbach, R.F., & Patton, J.R. (2002). Mental Retardation (6th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, Inc.

Bohmer, C.J.M., Taminiau, J.A.J.M., Klinkenberg-Knol, E.C., & Meuwissen, S.G.M. (2001). The prevalence of constipation in institutionalized people with intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 45, 212–218. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2788.2001.00300.x

Brophy, G.M., Bell, R., Classen, J., et al. (2012). Guidelines for the evaluation and management of status epilepticus. Neurocritical Care, 17(1), 3–23. doi:10.1007/s12028-012-9695-z

Brown, G.W. (1990). Rule-making and justice: A cautionary tale. Mental Retardation, 28(2), 83–87.

Campaign 2000 (2003). Honouring our promises: Meeting the challenge to end child and family poverty: 2003 report card on child poverty in Canada. Retrieved from http://www.campaign2000.ca/rc/rc03/NOV03ReportCard.pdf

Campbell, V. (2001). Disability and Health Program, National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disability, Centers for Disease Control. A Presentation to the Coleman Institute for Cognitive Disabilities, University of Colorado at Aspen. Retrieved from http://colemaninstitute.org/institute-annual-conferences/11-conferences/2001-conference/42-2001-conference-agenda

Corbin, S., Malina, K., & Shepherd, S. (2005). Special Olympics world summer games 2003 healthy athletes screening data. Washington DC: Special Olympics, Inc.

Crosse, S.B., Kaye, E., & Ratnofsky, A.C. (1993). A report on the maltreatment of children with disabilities [Contract No. 105-89-11639]. Washington DC: Westat Inc. National Center on Child Abuse and Neglect.

Department of Health (2001). Valuing people: A new strategy for learning disability for the 21st century. London UK.

Department of Health (2009). Valuing people now: A new three-year strategy for people with learning disability. Making it happened for everyone. London UK.

Drew, C.J. & Hardman, M.L. (2004). Mental retardation: A lifespan approach to people with intellectual disabilities (8th ed.). Upper Saddle River NJ: Pearson Education, Inc.

Emerson, E. (2011). Health status and health risks of the “hidden majority” of adults with intellectual disability. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 49(3), 155–165.

Emerson, E., & Baines, S. (2010). Health inequities and people with learning disabilities in the UK: 2010. Retrieved from http://www.improvinghealthandlives.org.uk/uploads/doc/vid_7479_IHaL2010-3HealthInequality2010.pdf

Epilepsy Canada, (n.d.). Did You Know? [Fact sheet]. Toronto ON. Retrieved from http://www.epilepsy.ca/en-ca/facts/epilepsy-facts.html

Havercamp, S., Scandlin, D., & Roth, M. (2004). Health disparities among adults with developmental disabilities, adults with other disabilities, and adults not reporting disability in North Carolina. Public Health Reports, 119, 418–426.Forster-Gibson, C. & Berg, J. (2011). Health watch table – Down Syndrome. Toronto ON: Surrey Place Centre. Retrieved from http://www.surreyplace.on.ca/

Heslop, P., Blair, P.S., Fleming, P., Hoghton, M., Marriott, A., & Russ, L. (2014). The Confidential Inquiry into premature deaths of people with intellectual disabilities in the UK: A population-based study. The Lancet, 383(9920), 889–895. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62026-7

Horwitz, S.M., Kerker, B.D., Owens, P.L., & Zigler, E. (2000). The health status and needs of individuals with mental retardation. New Haven CT: Yale University.

Lennox, N., Bain, C., Rey-Conde, T., Purdie, D., Bush, R., & Pandeya, (2007). Effects of a comprehensive health assessment programme for Australian adults with intellectual disability: A cluster randomized trial. International Journal of Epidemiology, 36, 139–146. doi:10.1093/ije/dy1254

Manitoba Family Services and Housing (2000). Workshop on the Vulnerable Persons’ Act and protection protocols. Brandon MB, Canada.

Melrose, S., Wishart, P., Urness, C., Forman, B., Holub, M., & Denoudsten, A. (2013). Supporting persons with developmental disabilities and co-occurring mental illness: An action research project. Canadian Journal of Psychiatric Nursing Research, 3, 32–40.

Mencap (2004). Treat me right! Better health care for people with learning disability. Retrieved from http://www.mencap.org.uk/sites/default/files/documents/2008-03/treat_me_right.pdf

Mencap (2007). Death by indifference. Retrieved from http://www.nhslothian.scot.nhs.uk/Services/AZ/LearningDisabilities/CurrentReports/DeathByIndiference.pdf

Morad, N., Nelson, N.P., Merrick, J., Davidson, E.C., & Carmeli, E. (2007). Prevalence and risk factors of constipation in adults with intellectual disability in residential centers in Israel. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 28(6), 580–586.

Moran, J., Hogan, M., Srsic-Stoehr, K., Service, K., & Rowlett, S. (2013). Aging and Down syndrome: A health and well-being guidebook. National Down Syndrome Society. Retrieved from https://www.ndss.org/Global/Aging%20and%20Down%20Syndrome.pdf

Morin, D., Merineau-Cote, J., Ouellette-Kuntz, H., Tasse, M.J., & Kerr, M. (2012). A comparison of the prevalence of chronic disease among people with and without intellectual disability. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 117(6), 455–463. doi:10.1352/1944-7558-177.6.455

National Association for Down Syndrome (2012). Facts about Down syndrome. [Fact sheet]. Chicago IL. Retrieved from http://www.nads.org/pages_new/facts.html

NHS Scotland (2004). Health needs assessment report – summary: People with learning disabilities in Scotland. Glasgow, Scotland.

Nocon, A. (2006). Equal treatment: Closing the gap: Background evidence for the DRC’s formal investigation into health inequities experienced by people with learning disabilities and mental health problems. Disability Rights Commission [Great Britain].

Ouellette-Kuntz, H., Garcin, N., Lewis, S., Minnes, P., Freeman, C., & Holden, J.J.A. (2004). Addressing health disparities through promoting equity. Ottawa ON.

Reichard, A. & Turnbull III, H.R. (2004). Perspectives of physicians, families, and case managers concerning access to health care by individuals with developmental disabilities. Mental Retardation, 42(3), 181–194.

Rimmer, J.H. & Yamaki, K. (2006). Obesity and intellectual disability. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews, 12(1), 22–27, doi: 10.1002/mrdd.20091

Royal College of Nursing (2006). Meeting the health needs of people with learning disability. London: Mencap.

Santos-Teachout, R., Evenhuis, H., Stewart, L., et al. (2007). Health guidelines for adults with an intellectual disability. International Association for the Scientific Study of Intellectual Disability and Developmental Disabilities. Retrieved from http://iassid.org/pdf/healthguidelines.pdf

Sobsey, D. & Doe, T. (1991). Patterns of sexual abuse and assault. Sexuality and Disability, 9(3), 243–259.

Stancliffe, R.J., Lakin, C.K., Larson, S., et al. (2011). Overweight and obesity among adults with intellectual disabilities who use intellectual disabilities/developmental disability services in 20 U.S. states. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 116(6), 401–418. doi:101352/1944-7558-116.6.401

Sullivan, W.G., Heng., J., Cameron, D., et al. (2006). Consensus guidelines for primary health care of adults with developmental disabilities. Canadian Family Physician, 52, 1410–1418.

U.S. Bureau of the Census (2003). Current population survey (CPS): 2003 annual social & economic supplement (ASEC). Washington DC. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/hhes/poverty/poverty02/pov02hi.html

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2002). Closing the gap: A national blueprint for improving the health of individuals with mental retardation. Washington DC: US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General.