This unit is based on a chapter from the book Living Political Ideas, which is part of the DD203 Power, Equality and Dissent module. It really attempts to do two things at once. It is about the core concepts and processes with which human groups that think of themselves as nations challenge the existing order and assert their right to a state of their own. And at the same time it is a kind of gentle introduction to how to study political ideas. It is more theoretical, or philosophical, than historical, but that doesn’t mean it has no purchase on the real world. The practical examples with which it works range from the bitter dispute between Palestine and Israel, to the ongoing debates about secession which threaten to break up old multinational states like the UK and Canada. If you have any apprehensions about ‘doing political theory’, I would simply say: there’s no need! Just work through the text, and by the end you will find yourself in possession of some powerful conceptual tools for thinking more clearly and incisively about one of the most urgent political problems of our time.

One thing which is very helpful to keep in mind when discussing ideas in politics is simply the different levels at which ideas can exist and get discussed. Here’s what I mean:

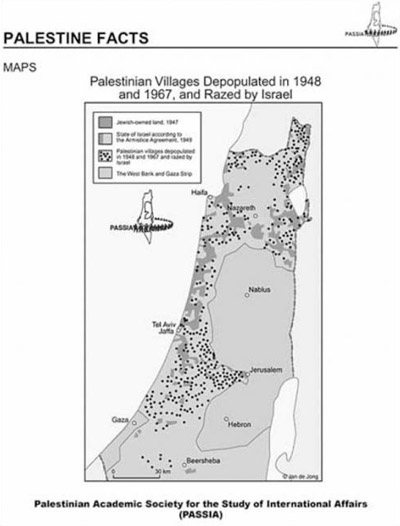

- Real world events happen: for example, Palestinians fighting for their own state.

- Actors in these events have ideologies or ‘fighting creeds’, which provide them with a source of identity and a justification for their political actions. For example, nationalism.

- Journalists, historians and other writers offer explanations of both the real world events and the ideologies in play. For example, Edward Said on Palestine and the wider Arab-Israeli conflict.

- Some political theorists make a more abstract and careful analysis of the core concepts, and ‘unpack’ or evaluate the arguments and claims made.

- Others go further, offering not only new ways of thinking about the core problems, but practical suggestions for policy-makers. For example, democratic ways of deciding on claims for secession.

One reason this can be hard to think about all at once is that real world events, such as conflicts about secession and self determination, are moving processes (like a film), whilst the analysis of key ideas is a bit like ‘freezing the frame’ and taking a magnifying glass to the words and ideas in play. In studying this unit you will be learning an important but quite tricky skill: how to critically examine concepts and theories partly by relating them to the real world.

OK. One final thing before you turn to the unit itself. A fundamental assumption of Open University teaching is that it is much more beneficial for a student to work actively with a text than simply to read on and on, passively trying to absorb and remember it all. Sometimes we set in-text activities or exercises to test your grasp of key points, but that is not what we are going to do here. Instead, I recommend the following. If you have the time, make some summary notes as you go along. One good way to do this is to mentally mark what seem to you important passages as you read, and then, at the end of each subsection perhaps, jot down what seem to you the main points you want to remember. At the end, you can check your list of points against that in the conclusion and see how well you have done.