Food-handling and Storage Procedures

Proper food handling and storage can prevent most foodborne illnesses. In order for pathogens to grow in food, certain conditions must be present. By controlling the environment and conditions, even if potentially harmful bacteria are present in the unprepared or raw food, they will not be able to survive, grow, and multiply, causing illness.

There are six factors that affect bacterial growth, which can be referred to by the mnemonic FATTOM:

- Food

- Acid

- Temperature

- Time

- Oxygen

- Moisture

Each of these factors contributes to bacterial growth in the following ways:

- Food: Bacteria require food to survive. For this reason, moist, protein-rich foods are good potential sources of bacterial growth.

- Acid: Bacteria do not grow in acidic environments. This is why acidic foods like lemon juice and vinegar do not support the growth of bacteria and can be used as preservatives

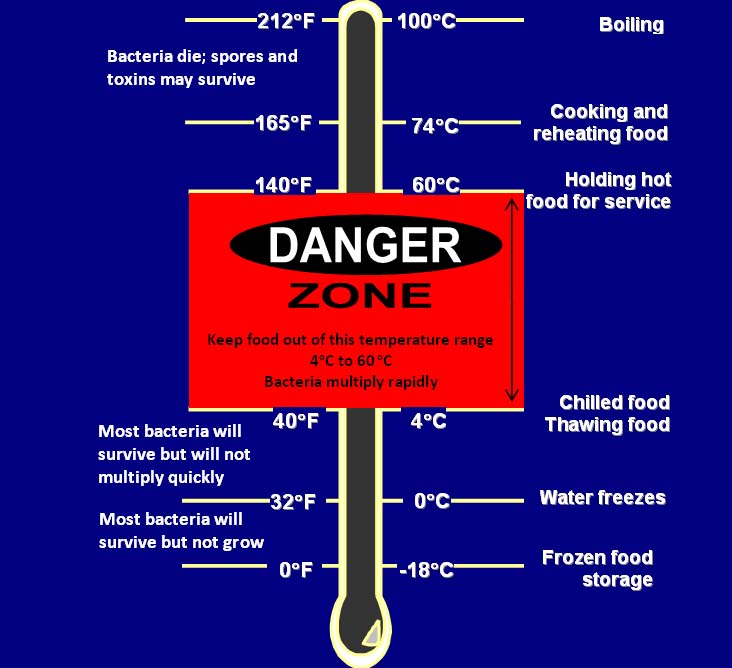

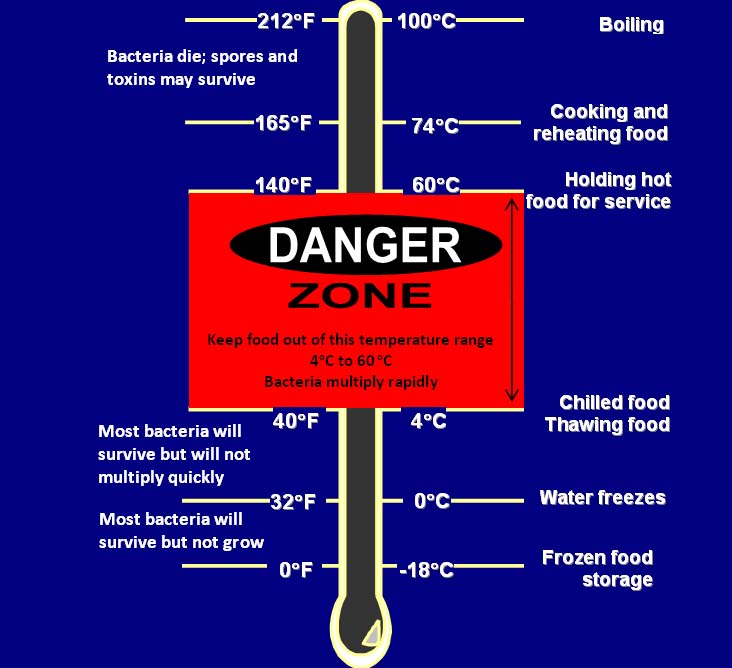

- Temperature: Most bacteria will grow rapidly between 4°C and 60°C (40°F and 140°F). This is referred to as the danger zone (see the section below for more information on the danger zone).

- Time: Bacteria require time to multiply. When small numbers of bacteria are present, the risk is usually low, but extended time with the right conditions will allow the bacteria to multiply and increase the risk of contamination

- Oxygen: There are two types of bacteria. Aerobic bacteria require oxygen to grow, so will not multiply in an oxygen-free environment such as a vacuum-packaged container. Anaerobic bacteria will only grow in oxygen-free environments. Food that has been improperly processed and then stored at room temperature can be at risk from anaerobic bacteria. A common example is a product containing harmful Clostridium botulinum (botulism-causing) bacteria that has been improperly processed during canning, and then is consumed without any further cooking or reheating.

- Moisture: Bacteria need moisture to survive and will grow rapidly in moist foods. This is why dry and salted foods are at lower risk of being hazardous.

Identifying Potentially Hazardous Foods (PHFs)

Foods that have the FATTOM conditions are considered potentially hazardous foods (PHFs). PHFs are those foods that are considered perishable. That is, they will spoil or “go bad” if left at room temperature. PHFs are foods that support the growth or survival of disease-causing bacteria (pathogens) or foods that may be contaminated by pathogens.

Generally, a food is a PHF if it is:

- Of animal origin such as meat, milk, eggs, fish, shellfish, poultry (or if it contains any of these products)

- Of plant origin (vegetables, beans, fruit, etc.) that has been heat-treated or cooked

- Any of the raw sprouts (bean, alfalfa, radish, etc.)

- Any cooked starch (rice, pasta, etc.)

- Any type of soya protein (soya milk, tofu, etc.)

Table 2 identifies common foods as either PHF or non-PHF.

| PHF | Non-PHF |

| Chicken, beef, pork, and other meats | Beef jerky |

| Pastries filled with meat, cheese, or cream | Bread |

| Cooked rice | Uncooked rice |

| Fried onions | Raw onions |

| Opened cans of meat, vegetables, etc. | Unopened cans of meat, vegetables, etc. (as long as they are not marked with “Keep Refrigerated”) |

| Tofu | Uncooked beans |

| Coffee creamers | Cooking oil |

| Fresh garlic in oil | Fresh garlic |

| Fresh or cooked eggs | Powdered eggs |

| Gravy | Flour |

| Dry soup mix with water added | Dry soup mix |

Table 2. Common PHF and non-PHFs

The Danger Zone

One of the most important factors to consider when handling food properly is temperature. Table 3 lists the most temperatures to be aware of when handling food.

| Celsius | Fahrenheit | |

| 100° | 212° | Water boils |

| 60° | 140° | Most pathogenic bacteria are destroyed. Keep hot foods above this temperature. |

| 20° | 68° | Food must be cooled from 60°C to 20°C (140°F to 68°F) within two hours or less |

| 4° | 40° | Food must be cooled from 20°C to 4°C (68°F to 40°F) within four hours or less |

| 0° | 32° | Water freezes |

| –18° | 0° | Frozen food must be stored at –18°C (0°F) or below |

Table 3. Important temperatures to remember

Figure 1. Danger Zone Chart, Used with permission from BC Centre for Disease Control (BCCDC)

The range of temperature from 4°C and 60°C (40°F and 140°F) is known as the danger zone, or the range at which most pathogenic bacteria will grow and multiply.

Time-temperature Control of PHFs

Pathogen growth is controlled by a time-temperature relationship. To kill micro-organisms, food must be held at a sufficient temperature for a sufficient time. Cooking is a scheduled process in which each of a series of continuous temperature combinations can be equally effective. For example, when cooking a beef roast, the microbial lethality achieved at 121 minutes after it has reached an internal temperature of 54°C (130°F) is the same as if it were cooked for 3 minutes after it had reached 63°C (145°F).

Table 4 show the minimum time-temperature requirements to keep food safe. (Other time-temperature regimens might be suitable if it can be demonstrated, with scientific data, that the regimen results in a safe food.)

| Critical control point | Temperature |

| Refrigeration | |

- Cold food storage: all foods

| 4°C (40°F) or less |

| Freezing | |

- Frozen food storage – all foods

| –18°C (0°F) or less |

- Parasite reduction in fish intended to be served raw, such as sushi and sashimi

- Raw fish

| –20°C (–4°F) for 7 days or, –35°C (–31°F) in a blast freezer for 15 hours |

| Cooking | |

- Food mixtures containing poultry, eggs, meat, fish, or other potentially hazardous foods

| Internal temperature of 74°C (165°F) for at least 15 seconds |

| | Internal temperature of 54°C to 60°C (130°F to 140°F) |

| | Internal temperature of 60°C to 65°C (140°F to 150°F) |

- Pork, lamb, veal, beef (medium-well)

| Internal temperature of 65°C to 69°C (150°F to 158°F) |

- Pork, lamb, veal, beef (well done)

| Internal temperature of 71°C (160°F) |

| | Internal temperature of 74°C (165°F) for 15 seconds |

| | 74°C (165°F) |

| | 70°C (158°F) |

| | 63°C (145°F) for 15 seconds |

| | 70°C (158°F) |

| Holding, cooling, and reheating | |

| | 60°C (140°F) |

| | 60°C to 20°C (140°F to 68°F) within 2 hours and 20°C to 4°C (68°F to 40°F) within 4 hours |

| | 74°C (165°F) for at least 15 seconds |

Table 4. Temperature control for PHFs

The Top 10 List: Do’s and Don’ts

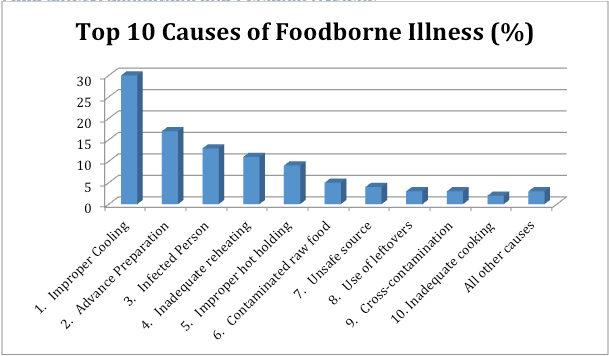

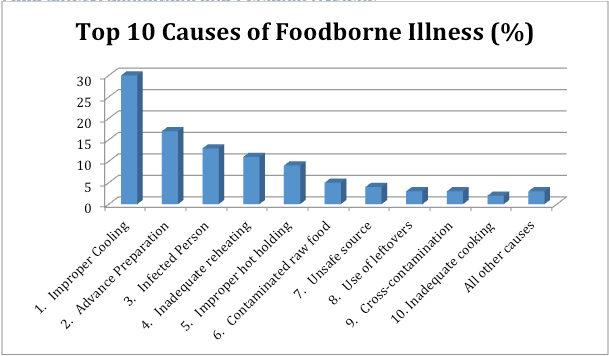

Figure 1 illustrates the top 10 improper food-handling methods and the percentage of foodborne illnesses they cause.

Figure 1. Top 10 causes of foodborne illness. Chart created by go2HR under CC BY.

This section describes each food-handling practice outlined in the top 10 list and the ways to prevent each problem.

1. Improper cooling

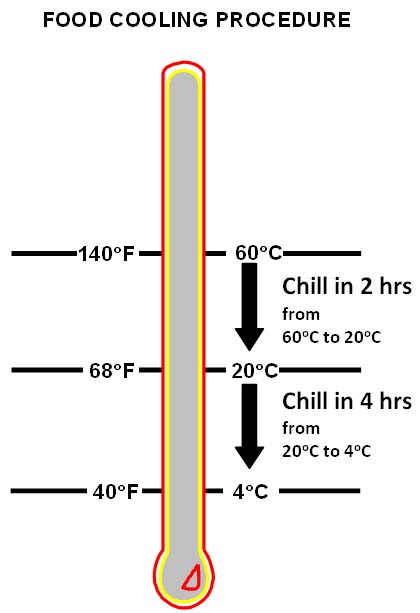

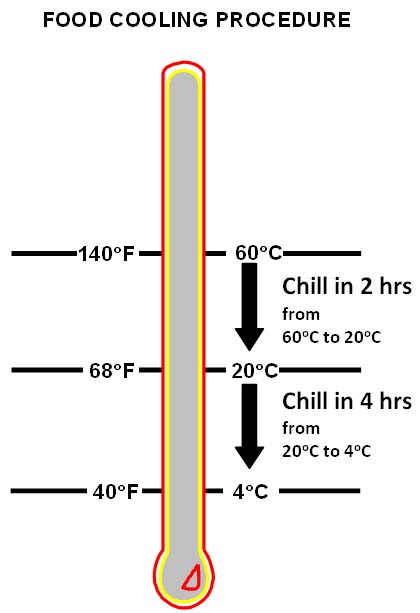

Many people think that once a food has been properly cooked, all disease-causing organisms (pathogens) have been killed. This is not true. Some pathogens can form heat-resistant spores, which can survive cooking temperatures. When the food begins cooling down and enters the danger zone, these spores begin to grow and multiply. If the food spends too much time in the danger zone, the pathogens will increase in number to a point where the food will make people sick. That is why the cooling process is crucial. Cooked food must be cooled from 60°C to 20°C (140°F to 70°F) in two hours or less, AND then from 20°C to 4°C (70°F to 40°F) in four hours or less.

Figure 3. Food Cooling Procedure, used with permission from BC Centre for Disease Control (BCCDC)

Even in modern walk-in coolers, large cuts of meat will not cool down properly. Neither will whole poultry. Even large pots (4 L/1 gal. or more) of soup, stews, gravy, etc., can take a day or more to cool to 4°C (40°F). However, you can cool these foods down quickly by using one or more of the following methods depending on the type of food being cooled:

- Place the food in shallow pans (with the food no deeper than 5 cm/2 in.) and put the pans in the cooler.

- When the food is cooling, do not tightly cover. Doing so only seals in the heat.

- Do not stack the shallow cooling pans during the cooling step. This will defeat the purpose of shallow panning by preventing cold air from reaching the food. You may need to add more shelves to your cooler.

- Cut large cuts of meat or whole poultry into smaller or thinner portions. Then place these portions into shallow pans for cooling.

- Use cooling wands or cooling sticks to cool foods quickly.

- Use rapid cooling equipment such as walk-in coolers with wire shelving and good air flow. Home-style refrigerators or reach-ins do not cool food well.

- Stir the food in a container placed in an ice-water bath.

- Use containers that help heat transfer, such as stainless steel or aluminum. Plastic does not transfer heat well.

- Use ice as an ingredient (e.g., in stews or soups).

- For large pots of cooked desserts (e.g., custard), divide it into serving sizes and then cool.

2. Advance preparation

Advance preparation is the cause of many food-poisoning outbreaks, usually because food has been improperly cooled. Often, foods that are prepared well before serving spend too much time in the danger zone. This may happen for one or more of the following reasons:

- The food is left out at room temperature too long.

- The food is not heated or reheated properly (to a high enough temperature), or not cooled properly.

- The food is brought in and out of the danger zone too many times (e.g., cooked, hot held, cooled, reheated, hot held, cooled, reheated again).

To prevent problems of advance preparation:

- Try to prepare all foods for same-day use and as close to serving time as possible.

- To prevent outside contamination of foods prepared in advance, cover them tightly after they have been properly cooled.

- Reheat leftovers only once. If leftovers are not consumed after being reheated, throw them out.

- For foods prepared and held refrigerated in the cooler for more than 24 hours, mark the date of preparation and a “serve by” date. Generally, PHFs should be thrown out if not used within three days from date they were made.

- If you must prepare foods in advance, be sure you properly cool and refrigerate them.

3. Infected person

Many people carry pathogens somewhere on or in their bodies without knowing it—in their gut, in their nose, on their hands, in their mouth, and in other warm, moist places. People who are carrying pathogens often have no outward signs of illness. However, people with symptoms of illness (diarrhea, fever, vomiting, jaundice, sore throat with a fever, hand infections, etc.) are much more likely to spread pathogens to food.

Another problem is that pathogens can be present in the cooked and cooled food that, if given enough time, can still grow. These pathogens multiply slowly but they can eventually reach numbers where they can make people sick. This means that foods that are prepared improperly, many days before serving, yet stored properly the entire time can make people sick.

Some pathogens are more dangerous than others (e.g., salmonella, E. coli, campylobacter). Even if they are only present in low numbers, they can make people very sick. A food handler who is carrying these kinds of pathogens can easily spread them to foods – usually from their hands. Ready-to-eat food is extra dangerous. Ready-to-eat food gets no further cooking after being prepared, so any pathogens will not be killed or controlled by cooking.

To prevent problems:

- Make sure all food handlers wash their hands properly after any job that could dirty their hands (e.g., using the toilet, eating, handling raw meats, blowing their nose, smoking).

- Food handlers with infected cuts on their hands or arms (including sores, burns, lesions, etc.) must not handle food or utensils unless the cuts are properly covered (e.g., waterproof bandage covered with a latex glove or finger cot).

- When using gloves or finger cots, food handlers must still wash their hands. As well, gloves or cots must be replaced if they are soiled, have a hole, and at the end of each day.

- Food handlers with infection symptoms must not handle utensils or food and should be sent home.

- Where possible, avoid direct hand contact with food – especially ready-to-eat foods (e.g., use plastic utensils plastic or latex gloves).

4. Inadequate reheating for hot holding

Many restaurants prepare some of menu items in advance or use leftovers in their hot hold units the next day. In both cases, the foods travel through the danger zone when they are cooled for storage and again when they are reheated.

Foods that are hot held before serving are particularly vulnerable to pathogens. In addition to travelling through the danger zone twice, even in properly operating hot hold units, the food is close to the temperature that will allow pathogens to grow.

To prevent problems:

- Do not use hot hold units to reheat food. They are not designed for this purpose. Instead, rapidly reheat to 74°C (165°F) (and hold the food at that temperature for at least 15 seconds before putting it in the hot hold unit. This will kill any pathogens that may have grown during the cool-down step and the reheat step.

- If using direct heat (stove top, oven, etc.), the temperature of the reheated food must reach at least 74°C (165°F) for at least 15 seconds within two hours. Keep a thermometer handy to check the temperature of the food.

- If using a microwave, rotate or stir the food at least once during the reheat step, as microwaves heat unevenly. As well, the food must be heated to at least 74°C (165°F) and then stand covered for two minutes after reheating before adding to the hot hold unit. The snapping and crackling sounds coming from food being reheated in a microwave do not mean the food is hot.

5. Improper hot holding

Hot hold units are meant to keep hot foods at 60°C (140°F) or hotter. At or above this temperature, pathogens will not grow. However, a mistake in using the hot hold unit can result in foods being held in the super danger zone – between 20°C and 49°C (70°F and 120°F), temperatures at which pathogens grow very quickly.

To prevent problems:

- Make sure the hot hold unit is working properly (e.g., heating elements are not burnt out; water is not too low in steam tables; the thermostat is properly set so food remains at 60°C (140°F) or hotter) Check it daily with a thermometer.

- Put only already hot (74°C/165°F) foods into the hot hold unit.

- Preheat the hot hold unit to at least 60°C (140°F) before you start putting hot foods into it.

- Do not use the hot hold unit to reheat cold foods. It is not designed for or capable of doing this rapidly.

- After the lunch or dinner rush, do not turn off the heat in the hot hold unit and then leave the food there to cool. This is very dangerous. When you do this, the food does not cool down. It stays hot in the super danger zone and lets pathogens grow quickly. Foods in hot hold units should be taken out of the units after the meal time is over and cooled right away.

6. Contaminated raw food or ingredient

We know that many raw foods often contain pathogens, yet certain foods are often served raw. While some people believe these foods served raw are “good for you,” the truth is that they have always been dangerous to serve or eat raw. Some examples include:

- Raw oysters served in the shell

- Raw eggs in certain recipes (e.g., Caesar salad, eggnog made from raw eggs)

- Rare hamburger

- Sushi/sashimi

- Steak tartare

These foods have caused many food-poisoning outbreaks. Always remember: you cannot tell if a food contains pathogens just by look, taste, or smell.

To prevent problems:

- Buy all your foods or ingredients from approved suppliers.

- If available, buy foods or ingredients from suppliers who also have food safety plans for their operations.

- Where possible, use processed or pasteurized alternatives (e.g., pasteurized liquid eggs).

- Never serve these types of foods to high-risk customers (e.g., seniors, young children, people in poor health, people in hospitals or nursing homes).

7. Unsafe source

Foods from approved sources are less likely to contain high levels of pathogens or other forms of contamination. Approved sources are those suppliers that are inspected for cleanliness and safety by a government food inspector. Foods supplied from unreliable or disreputable sources, while being cheaper, may contain high levels of pathogens that can cause many food-poisoning outbreaks.

Fly-by-night suppliers (trunk sales) often do not care if the product is safe to sell to you, but approved suppliers do! As well, many fly-by-night suppliers have obtained their product illegally (e.g., closed shellfish fisheries, rustled cattle, poached game and fish) and often do not have the equipment to properly process, handle, store, and transport the food safely.

Of particular concern is seafood from unapproved sources. Seafood, especially shellfish, from unapproved sources can be heavily contaminated with pathogens or poisons if they have been harvested from closed areas.

To prevent problems:

- Buy your food and ingredients from approved sources only. If you are not sure a supplier has been approved, contact your local environmental health officer. He or she can find out for you.

- Do not take the chance of causing a food-poisoning outbreak by trying to save a few dollars. Remember, your reputation is on the line.

8. Use of leftovers

Using leftovers has been the cause of many outbreaks of food poisoning because of improper cooling and reheating (of “hot” leftovers). Leftovers that are intended to be served hot pass through the danger zone twice (during the initial cooling of the hot food and when reheating). Those leftovers intended to be served without reheating, or as an ingredient in other foods (e.g., sandwich filler), go through the danger zone during cooling and then, when being prepared and portioned, often stay in the danger zone for another long period. The time in the danger zone adds up unless the food is quickly cooled and then quickly reheated (if being served hot), or kept cold until serving (if not being served hot).

Contamination can also occur with leftover foods when they are stored in the cooler. Improperly stored leftovers can accidentally be contaminated by raw foods (e.g., blood dripping from a higher shelf).

To prevent problems:

- Reheat leftovers only once. Throw out any leftovers that have already been reheated once.

- Do not mix leftover foods with fresh foods.

- Be sure to follow the proper cooling and reheating procedures when handling leftovers. These are critical control points.

- Cool leftovers in uncovered containers separate from any raw foods. After they are cooled, cover them tightly.

9. Cross-contamination

You can expect certain foods to contain pathogens, especially raw meat, raw poultry, and raw seafood. Use extreme caution when you bring these foods into your kitchen. Cross-contamination happens when something that can cause illness (pathogens or chemicals) is accidentally put into a food where not previously found. This can include, for example, pathogens from raw meats getting into ready-to-eat foods like deli meats. It can also include nuts (which some people are very allergic to) getting into a food that does not normally have nuts (e.g., tomato sauce).

To prevent problems:

- Use separate cutting boards, separate cleaning cloths, knives/utensils, sinks, preparation areas, etc., for raw and for ready-to-eat foods. Otherwise, wash all of these items with detergent and sanitize them with bleach between use.

- Use separate storage areas for raw and ready-to-eat foods. Always store ready-to-eat foods on separate shelves and above raw foods. Store dry foods above wet foods.

- Prepare ready-to-eat foods at the beginning of the day before the raw foods are prepared.

- After handling raw foods, always wash your hands properly before doing anything else.

- Keep wiping or cleaning cloths in a container of fresh bleach solution (30 mL/1 oz. of bleach per 4 L/1 gal. of water) when not in use.

- Use clean utensils, not your hands, to handle cooked or ready-to-eat foods.

- If a customer indicates a food allergy, follow all the same steps to avoid cross contamination and use separate or freshly sanitized tools and utensils to prepare food for the individual with the allergy.

10. Inadequate cooking

Proper cooking is one of the best means of making sure your operation does not cause a food-poisoning outbreak. Proper cooking kills all pathogens (except spores) or at least reduces their numbers to a point where they cannot make people sick. Inadequate cooking is often done by accident: for example, cooking still-frozen poultry or meat; attempting to cook a stuffed bird using the same time and temperature as an unstuffed bird; using an inexperienced cook.

To prevent problems:

- Don’t rely on cooking times alone. Check the internal temperature of the food being cooked.

- For large cuts of meat or large batches of food, check the temperature in several spots.

- Be extra careful when cooking partially frozen foods. There can be cold spots in the food that are not properly cooked. The normal cooking time will have to be increased.

- When grilling or frying meat, cook until the juices run clear. Cooked fish until it flakes easily. Make thin, not thick, hamburgers.