Chapter Summary

This chapter discusses the impacts of armed conflict on women and girls, including the renewed social vulnerabilities these conflicts cause. These vulnerabilities include rape, forced marriage, forced impregnation, indentured labour, sexual servitude, and the intentional spread of HIV/AIDS. During times of armed conflict, women are exploited in ways that relate to their reproductive responsibilities or gendered expectations of womanhood. However, women and girls are not merely victims in situations of inter- or intra-state violence. They can have critical perspectives on their position, make choices, and organize collectively. Women can take active roles in violence, such as joining the conflict, or participate in peace processes. The participation of women in formal peace processes is vital for a society to move forward during post-conflict periods, as indicated by the United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325. For example, the chapter mentions that women organized peace campaigns during the 1991 Balkan wars and the 2000 coup d’état in Fiji.

The chapter provides two case studies of women’s engagement in peace processes, one from a non-governmental perspective and another from a state perspective. Women for Women International was founded by Zainab Salbi and aims to help women survivors of war recover from their experiences. The organization has raised over $80 million throughout 17 years and has worked with over 250,000 women and girls. The chapter also discusses the increasing role of female peacekeeping forces. Since 2007, India has sent four Female Formed Police Units (FFPU) to Liberia, which has inspired women to join the national police force. Further, India’s FFPU has inspired Bangladesh and Nigeria to create their own.

Key Terms

- Blue Ribbon Campaign

- Female Formed Police Unit (FFPU)

- United Nations Development Fund for Women (UNIFEM)

- United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325

- Women in Black

- Zainab Salbi

Figure 5.1: Armed conflict disrupts families and has significant negative consequences for women. Although they are victims of war, they may also be agents of peace. Displaced Sudanese women, driven from their villages by Janjaweed militia, shelter at the Abu Shouk refugee camp in Darfur, Sudan.

Overview

By Dyan Mazurana

Women and girls experience armed conflict much the same way men and boys do. They are killed, injured, disabled and tortured. They are targeted with weapons and suffer social and economic dislocation. They suffer the psychosocial impact as loved ones die or they witness violence against their families and neighbors. They suffer the effects of violence before, during and after flight from a combat zone. They are at heightened risk of diseases, including sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) and HIV/AIDS. They are affected by the resource depletion resulting from armed conflict. They join, or are forced to join, armed forces or insurgency movements. They care for the wounded, sick, despairing and displaced, and may be among the most outspoken advocates for peace.

Significant and Lasting Harm

There is a growing body of evidence (ICRC 2001, UNIFEM 2002) that the long-term impact of armed conflict on women and girls may be exacerbated by their social vulnerability. The harm done to women and girls during and after armed conflict is significant, and often exposes them to further harm and violence. Gender-based and sexual violence such as rape, forced marriage, forced impregnation, forced abortion, torture, trafficking, sexual slavery and the intentional spread of STDs, including HIV/AIDS, are weapons of warfare integral to many of today’s conflicts. Women are victims of genocide and enslaved for labor. Women and girls are often viewed as culture bearers and reproducers of “the enemy” and thus become prime targets. Women are exploited because of their maternal responsibilities and attachments, which heighten their vulnerability to abuse.

Figure 5.2: Somalian women gather with their children at the Dadaab refugee camp in Eastern Kenya.

Armed conflicts also have indirect negative consequences that affect agriculture, livelihoods, infrastructure, public health and welfare provision, gravely disrupting the social order. Research shows that these repercussions affect women more adversely than men. As noted by Plümper and Neumayer (2006), while women typically live longer than men in peacetime, armed conflict decreases the gap between female and male life expectancy. Heavily ethnicized conflicts or wars within “failed states” are significantly more damaging to women’s health and life expectancy than other civil wars.

Women as Agents of War and Peace

Women and girls are not merely victims of armed conflict. They are active agents. They make choices, possess critical perspectives on their situations and organize collectively in response to those situations. Women and girls can perpetrate violence and can support violence perpetrated by others. They become active members of conflict because they are committed to the political, religious or economic goals of those involved in violence. This can mean, and has meant, taking up arms in liberation struggles, resistance to occupation or participation in struggles against inequality on race, ethnic, religious or class/caste lines.

Women and girls are also often active in peace processes before, during and after conflicts. Many women know the importance of peace processes and join a variety of grass-roots peace-building efforts aimed at rebuilding the economic, political, social and cultural fabric of their societies. In 1991, as the war in the Balkans was gaining momentum, Women in Black launched an antiwar campaign in the Balkans. In Fiji, as the tensions between Indo-Fijians and indigenous peoples were getting worse, leading to the coup d’état that occurred in 2000, women from both ethnic groups created the Blue Ribbon Campaign peace movement (Anderlini, 2007).

However, formalized processes of peace, including negotiations, accords and reconstruction plans, frequently exclude women’s and girls’ meaningful participation. Too often, women and girls actively involved in rebuilding local economies and civil society are pushed into the background when formal peace processes begin.

Post-Conflict Gains in Gender Relations

Finally, women and girls may gain from the changed gender relations that result from armed conflict. They sometimes acquire new status, skills and power that result from taking on new responsibilities when male heads of household are absent or deceased. These changes in women’s roles can challenge existing social norms. Women’s participation in household decisionmaking, civil society and the local economy and their ownership of land or goods may be altered, sometimes — although not always — to their benefit.

Figure 5.3: Bosnian Muslim women grieve among coffins of victims of the 1995 Srebrenica massacre. The remains were unearthed in 2010. The massacre shattered lives of widows and families of the 8,000 killed by Bosnian Serb troops in 1995.

The specific experience of women and girls in armed conflicts greatly depends upon their status in societies before armed conflict breaks out. Where cultures of violence and discrimination against women and girls exist prior to conflict, these abuses are likely to be exacerbated during conflict. Similarly, if women are not allowed to be part of decisionmaking before conflict, it is usually extremely difficult for them to become involved in decisions during the conflict itself or the peace process and post-conflict period. Thus, gender relations in pre-conflict situations as shaped by ethnicity, class, caste and age often set the stage for women’s and girls’ experiences and options during and after armed conflict.

The international community is increasingly aware of and responsive to the impact of armed conflict on women and girls (as shown, for instance, by the unanimous adoption in October 2001 of United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325, which included the special needs of women and girls during repatriation and resettlement, rehabilitation, reintegration and post-conflict reconstruction) and the importance of their participation in peace processes and the post-conflict period. Of paramount importance in any strategy to promote and attain women’s and girls’ rights during and after conflict is a context-specific, grounded understanding of how the conflict has affected different groups of women and their families.

Dyan Mazurana is a research director and associate professor at the Feinstein International Center, Tufts University, where she lectures on women’s and children’s human rights, war-affected civilian populations, armed opposition groups, armed conflict and peacekeeping at the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy. Author of four books, numerous articles and reports, she consults for governments, human rights and child protection organizations and U.N. agencies to improve efforts to assist youth and women affected by armed conflict. She has worked in South Asia, the Balkans and sub-Saharan Africa.

PROFILE: Zainab Salbi – Helping Women Recover from War

By Joanna L. Krotz

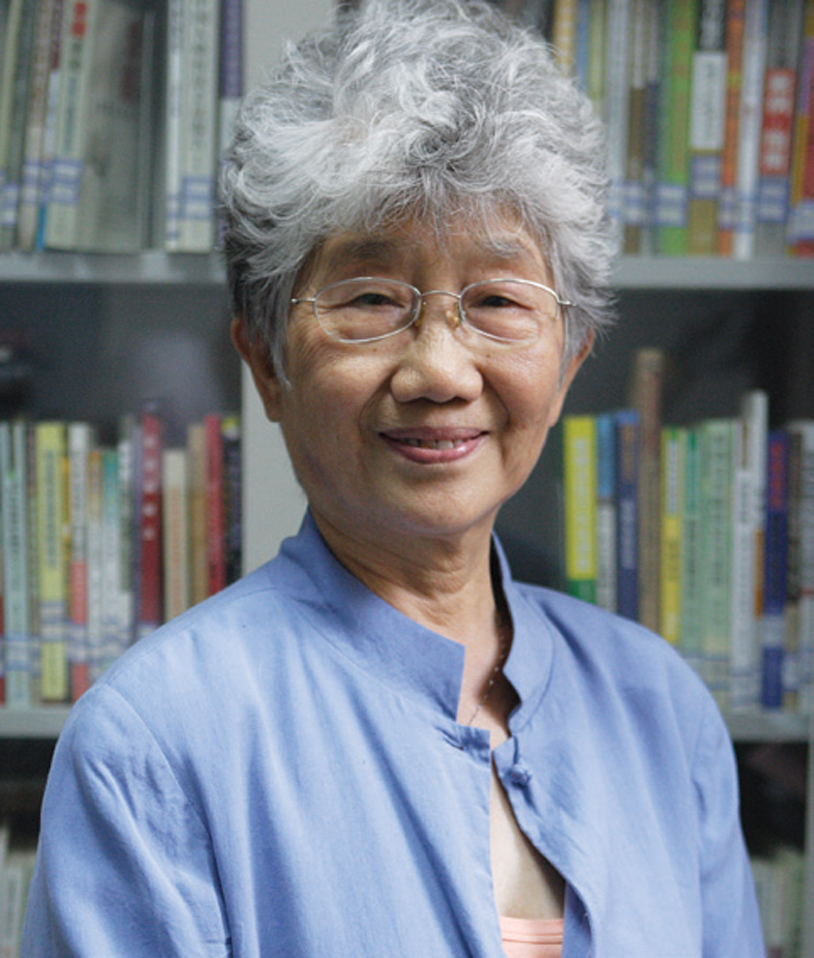

Figure 5.4: Zainab Salbi saw first-hand women suffering in war-torn Bosnia. She responded by founding Women for Women International, which has brought hope to thousands of women in conflict zones around the world.

Charismatic and forthright, Zainab Salbi instantly grabs your attention. And that’s even before you see her resume or hear her compelling personal story.

At age 41, she is recognized around the world as the founder and chief executive officer of Women for Women International, a nongovernmental organization that helps women survivors of war to rebuild their lives. Over its 17-year history, Women for Women has distributed nearly $80 million in direct aid, microcredit loans and programs serving more than 250,000 women worldwide. Known as a fierce and effective champion, Salbi travels constantly, working with local groups to secure women’s safety and economic prosperity in some of the world’s most devastated regions, including the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Rwanda, Sudan and Afghanistan. Yet little in Zainab Salbi’s fairytale childhood could have foretold such a calling.

Figure 5.5: Zainab Salbi meets with women in Rwanda.

Growing up in the privileged precincts of Baghdad, she was the cherished daughter of an elite Iraqi family. Her early years were an idyllic blur of school and family outings, with lessons in piano and ballet. In her best-selling memoir, Between Two Worlds, published in 2005, Salbi describes sunlit days of driving around in the family car alongside her mother, shopping, running errands, paying social calls: “As we drove … along the boulevards lined with palm trees heavy with dates … I took in my city through the passenger-side window — old Baghdad with its dark arcaded souk [market] where men hammered out copper and politics, and the new Baghdad with its cafes and Al-Mansour boutiques.” Most everything Salbi learned in her early years, she writes, came through her adored mother.

Life changed when she turned 11, although it would be years before she could pinpoint the shift. Saddam Hussein assumed power and soon anointed Salbi’s father, a commercial aviator, as the ruler’s personal pilot. Increasingly, through Salbi’s teenage years, the family felt the effects of Saddam’s regime, both his patronage and his oppressive heel. She recalls halcyon weekends at Saddam’s compound, calling him “Amo” or “Uncle,” playing with his kids around the pool and, as she was constantly cautioned, willfully ignoring the fear and violence rising around her. Later, living in the United States, particularly after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, that intimacy with Saddam would haunt her. “I kept it a secret and told no one,” she says. “I was afraid if I told people I knew Saddam, my face would be erased and all anyone would see in me was Saddam.”

When Salbi was 19, her progressive mother suddenly announced that she’d arranged a marriage for Salbi to a much older Iraqi banker living in America. “It was very painful,” says Salbi. “My mother had always told me not to depend on any man. She was passionate, adamant about it. Then all of a sudden I was being whisked away from home. I had no idea what she was talking about.” Twenty years on, you still hear the hurt, the loss and indignation in Salbi’s voice. Dutifully, Salbi went off to be a bride in Chicago.

And she landed in a nightmare. “The man who was my husband turned out to be abusive,” she says. When Salbi proved unbowed, he raped her. She walked out after three months. “I had $7 in my pocket, some designer clothes on my back and about $20 a week from family funds to survive,” she says.

It was 1990 and Saddam had just invaded Kuwait. After Operation Desert Storm was launched, there was no going home to Iraq for Salbi.

Over time, she built a life in the United States. It was years before she saw her family again. And years after that, when her mother was ill and dying, that Salbi finally found the voice to ask why she’d been sent away. Saddam had his eye on you, her mother told her. The only escape route from becoming Saddam’s plaything was an arranged marriage on another continent.

In 1993, Salbi was living in Washington, remarried to a Palestinian student named Amjad Atallah, when she read a news story about the Bosnian war and rape camps where some 20,000 women were raped. The couple decided to travel to Bosnia to help.

Salbi and Atallah returned to Washington determined to find a group that would provide aid for Bosnian rape victims. But none existed. So, still on a student budget, the couple founded their own organization, Women for Women, and began to help the women in the Balkans.

By 2004, Salbi, now divorced, had expanded Women for Women to its international mission. Appearances on the Oprah Winfrey Show, which draws millions of viewers, boosted both her profile and the organization as donations climbed. In the 15 years since arriving in the United States, Salbi became a prominent humanitarian and an award-winning women’s rights advocate, honored by President Bill Clinton for her work in Bosnia. What hadn’t changed were her secrets about Saddam and her first marriage.

On a trip to the eastern Congo that year, Salbi was interviewing a woman named Nabito, then age 52. Rebels had raped Nabito and her three daughters. “There were so many she said she couldn’t tell how many were around and how many had raped her,” says Salbi, remembering. Salbi asked Nabito whether she wanted her story kept quiet. Instead, says Salbi, “she said, ‘If I could tell my story to the whole world, I would, so other women would not have to go through what I’ve gone through. So you go and tell my story.’”

Nabito’s courage — and her resilient conviction — pushed Salbi into breaking her own silence. Owning her past also has changed the way Zainab Salbi works. “Before, I’d be the humanitarian worker with connections and aid interviewing other women. Now, I am their equal. I’m not there to save anyone. I actually am one of the women I’m trying to help.”

Joanna L. Krotz is a multimedia journalist and speaker whose work has appeared in the New York Times, Worth, Money and Town & Country and on MSN and Entrepreneurship.org. She is the author of The Guide to Intelligent Giving and founder of the Women’s Giving Institute, an organization that educates donors about strategic philanthropy.

PROJECT: Liberia – Female Peacekeepers Smash Stereotypes

By Bonnie Allan

Since its groundbreaking deployment in 2007, India has sent four all-female police units to Liberia, each serving a one-year rotation. Their success in the postwar country has inspired other nations to defy tradition and deploy more female troops in U.N. peacekeeping roles.

Five days after an elaborate marriage ceremony in southern India, 28-year-old Rewti Arjunan traded her red silk sari for a blue camouflage police uniform and flew to the West African country of Liberia.

The young bride is serving in one of the world’s few all-female police units deployed to a United Nations peacekeeping mission.

“In India, we are quite traditional with these things. My husband, he was against it,” admits Arjunan, who had never before traveled outside India. The trained police officer gave her future husband an ultimatum.

“I told him, ‘If you permit me to go on this mission, I will marry you.’”

Now, Arjunan’s life is anything but traditional. She is helping to change the face of international policing in a post-conflict country.

Since its groundbreaking deployment in 2007, India has sent four Female Formed Police Units (FFPU) to Liberia, each serving a one-year rotation. More than 100 female police officers trained in crowd control and conflict resolution make up the FFPU at any one time. They are supported by about two dozen men who serve as drivers, cooks and logistical coordinators.

The FFPU is primed for rapid response to any violence that might erupt in this country of 3.8 million, which still lacks a strong army or armed police force.

Two bloody civil wars, between 1989 and 1996, and again from 1999 to 2006, killed about 250,000 Liberians, displaced hundreds of thousands more, traumatized women with rampant sexual violence, destroyed infrastructure such as schools, hospitals and roads, and corrupted the justice system.

Eight years after the war ended, almost 9,500 U.N. peacekeepers help maintain the fragile peace.

“The greatest deed is to protect humanity. I got this chance, and I thought, ‘I want to live this,’” says Arjunan.

The Female Formed Police Unit is a symbol of progress for U.N. Security Council Resolution 1325 on women, peace and security, which stipulates that peacekeeping missions support women’s participation in post-conflict peace building.

Figure 5.6: A member of the United Nations first all-female peacekeeping force stands guard with fellow officers after arriving at the Monrovia, Liberia, airport.

The United Nations’ ultimate goal is gender parity in the civilian, military and police sectors, but, globally, women make up just 8.2 percent of roughly 13,000 U.N. police and only two percent of military police.

India has scored high marks for pioneering an all-female police unit, serving alongside other female officers from Nigeria and elsewhere, in a country that boasts Africa’s first female head of state, Ellen Johnson Sirleaf.

By day, the Indian police officers stand in the hot sun guarding the president’s office, and, by night, they patrol crime-ridden areas of the capital, Monrovia.

As the rain trickles down on the dark streets of Monrovia’s Congo Town, Arjunan sits in the back seat of a U.N. police vehicle with her hair tucked inside a blue beret and a pistol strapped to her waist. Beside her, 25-year-old Pratiksha Parab holds an AK-47 rifle and peers out the window.

Their job is to protect Liberia National Police (LNP) officers, who are not armed, as they patrol to deter armed robberies and rape. “Most of the violent crimes are at night, and the criminals use weapons,” says LNP Commander Gus Hallie. “So, with our FFPU counterparts on our side, with arms, we feel we can battle with criminals.”

As they patrol, the U.N. police observer and the LNP officer joke that “Indian women are tough.” Arjunan smiles, pleased, but she explains why she is a good peacekeeper.

“Women are not aggressive. We come in a polite way. This presence can maintain the peace. We are loving by nature.”

There are many stereotypes attached to female peacekeepers: more nurturing, more communicative, less intimidating. The label that makes Contingent Commander Usher Kiran cringe, though, is “soft.”

“I don’t think there is a difference between female and male,” says Kiran, a 22-year police veteran, as she sits under a poster of Mahatma Gandhi.

“If you are putting on the same uniform, you are doing the same duty, you are having the same authority as the males.”

“Where we found a difference [between male and female peacekeepers] is in their perceptions of their role,” explains the U.N.’s gender adviser in Liberia, Carole Doucet. “The women see themselves as more broadly involved in the community.”

Doucet says the U.N.’s female police, known as “blue helmettes,” have inspired Liberian women to join the national police force. In 2007, only six percent of Liberia’s police were women. Today, that proportion has risen to 15 percent, with roughly 600 female officers.

The Indian women also sponsor an orphanage, teach self-defense and computer classes to local women, and — despite limited English — reach out to survivors of sexual abuse.

“I can be scared to talk to a man,” whispers a 16-year-old rape victim, who cannot be identified, at a safe home for girls in Monrovia. “A woman is better. She is like an auntie or mother.”

Figure 5.7: Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton greets a U.N. peacekeeper in Monrovia. Clinton has strongly supported Liberian President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf in promoting democracy and development. In 2010 USAID invested more than $11 million in programs for women’s empowerment.

India’s all-female unit has inspired Bangladesh and Nigeria to create their own, while countries such as Rwanda and Ghana also are ramping up their female troop contributions to U.N. missions. Back at the Indian headquarters in Monrovia, Arjunan talks to her new husband over the Internet, using a webcam, for at least an hour every day. Although she’s a little homesick, Arjunan says she is proud to follow in the footsteps of other courageous women in India’s history.

“Many freedom fighters were ladies … fighting for justice. Fighting for good things.”

Bonnie Allan is a freelance journalist working in Liberia, West Africa. She worked as a journalist in Canada for more than a decade and holds a master’s degree in international human rights law from the University of Oxford.

Multiple Choice Questions

Questions

- Examples of violence against women during armed conflict include…

- Rape

- Forced marriage

- Forced impregnation

- Torture

- All of the above

- Reasons for women’s vulnerability during armed conflict mentioned in the chapter include…

- Women may be viewed as reproducers of the ‘enemy’ due to their maternal responsibilities

- Indirect negative consequences on agriculture, welfare provision, and infrastructure, which research shows has disproportionate impacts on the lives of women

- Many women lose their high-level government positions as the state disintegrates

- The gap between male and female expectancy increases

- Both A and B

- Women may also be active agents in conflict through actions such as…

- Taking up arms in struggles

- Involvement in decision-making mechanisms during peace processes

- Occupying a higher position of power in post-conflict periods

- Working to ensure that their social and household roles are not changed by periods of conflict

- All of the above

- Which United Nations Security Council Resolution (UNSC) included the importance of women’s participation in peace processes and the post-conflict period?

- UNSC Resolution 1333

- UNSC Resolution 1325

- UNSC Resolution 589

- UNSC Resolution 1034

- None of the above

- Women for Women International was founded by…

- Angelia Jolie Pitt

- Hillary Clinton

- Vandana Shiva

- Zainab Salbi

- None of the above

- Salbi was motivated by which conflict to create Women for Women International?

- Bosnian War

- Rwandan Civil War

- Gulf War

- Somali Civil War

- None of the above

- The first Female Formed Peacekeeping Unit (FFPU) was assembled by…

- Canada

- United States

- Germany

- India

- South Africa

- Some stereotypes of female peacekeepers include…

- More nurturing

- More communicative

- Less intimidating

- All of the above

- None of the above

- The country that produced Africa’s first female head of state is…

- Namibia

- Botswana

- Liberia

- Lesotho

- None of the above

- According to the chapter, which is an accurate difference between male and female peacekeepers?

- Female peacekeepers are less intimidating

- Male peacekeepers have more physical strength

- Female peacekeepers are likely to view their role as more community oriented

- Male peacekeepers are less nurturing

- All of the above

- In 2007, what percentage of Liberian peacekeepers were women?

- 6%

- 5%

- 20%

- 15%

- 10%

- What other countries formed FFPUs or increased their female presence in peacekeeping missions after India’s first delegation?

- Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and Portugal

- Bangladesh, Nigeria, Rwanda, and Ghana

- Brazil, Russia, Argentina, and Britain

- China, Japan, Korea, and Singapore

- None of the above

Answers

- The correct answer is E (all of the above).

- Both answers A and B are correct. Women may be viewed as producers of the ‘enemy’ due to their maternal responsibilities (answer A) and are indirectly affected by damages to agriculture, welfare provision, and infrastructure (answer B). The chapter does not mention that women lose high-level government positions (answer C), and because women on average live longer than men , the gap between male and female life expectancy decreases when women are adversely affected by armed conflict, rather than increasing (answer D).

- The correct answer is E. All the answers are attested as ways women assert agency in periods of conflict, although none are universal. Women may commit violence during conflict for various reasons, although in other situations they may avoid armed conflict (answer A). Women are sometimes involved in peace processes (answer B), but are too often pushed to the side. Women may occupy higher positions of power in post-conflict situations, but this depends on many factors, notably their position of power prior to when the conflict began (answer C). The role of women in their societies may change during conflict, or remain relatively similar, but neither is guaranteed (answer D).

- The correct answer is UNSC Resolution 1325 (answer B). UNSC 1333 called for a ban on all military assistance to the Taliban and closure of its camps in the year 2000 (answer A). UNSC 589 condemned the oppressive politics of South Africa’s apartheid system in the year 1985 (answer C). UNSC Resolution 1034 discussed violations of international humanitarian law in the former Yugoslavia (1995) (answer D).

- The correct answer is Zainab Salbi (answer D). Angelina Jolie Pitt (answer A) is an American actress who was appointed UNHCR Special Envoy in 2012. Hillary Clinton was the 2009 – 2013 U.S. Secretary of State and 2016 presidential candidate for the Democratic Party (answer B). Vandana Shiva is an Indian scholar, anti-globalization activist, and all around environmentalist (answer C).

- The correct answer is Bosnian War (answer A).

- The correct answer is India (answer D).

- The correct answer is all of the above (answer D).

- The correct answer is Liberia (answer C).

- Answer C is correct. Carle Doucet, the UN’s gender adviser in Liberia, stated that the women involved saw their role as more broadly involved in the community.

- The correct answer is 6% (answer A).

- The correct answer is B. India’s all-female unit has inspired Bangladesh and Nigeria to create their own, while countries such as Rwanda and Ghana have ramped up their female troop contributions.

Discussion Questions

- How are women specifically vulnerable during periods of armed conflict?

- What is the connection between armed conflict, failed states, and violence against women? Is a strong state needed to ensure that women’s rights are protected?

- Look beyond the chapter to find some examples of women’s active involvement in combating violence against women. Please use examples from both the global South and the global North.

- Are there any challenges posed by the global influence of Western or American women’s rights organization?

- What are the strengths and limitations of Resolution 1325 in increasing the role of women in peacekeeping?

- Please offer an example of when and where Resolution 1325 was used. (Outside research)

- What would be some explanations for why a peace process did not lead to a post-conflict situation which improved the status of women?

Essay Questions

- How are women specifically vulnerable during periods of armed conflict?

- What is the connection between armed conflict, failed states, and violence against women? Is a strong state needed to ensure that women’s rights are protected?

- Look beyond the chapter to find some examples of women’s active involvement in combating violence against women. Please use examples from both the global South and the global North.

- Are there any challenges posed by the global influence of Western or American women’s rights organization?

- What are the strengths and limitations of Resolution 1325 in increasing the role of women in peacekeeping?

- Please offer an example of when and where Resolution 1325 was used. (Outside research)

- What would be some explanations for why a peace process did not lead to a post-conflict situation which improved the status of women?

Additional Resources

Bacon, L. “Reform: Improving Representation and Responsiveness in a Post-Conflict Setting.” Journal of International Peacekeeping 4, 372 – 397: (2015).

Explores efforts by the Liberian National Police to enhance training to address sexual and gender-based violence and increasing female officers.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13533312.2015.1059285

Gaestel, A. & Shelly, A. Female UN Peacekeepers: an all-too-rare sight. Guardian. (2015).

Re-examines the progress made on realizing the United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325.

https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2015/jan/22/female-united-nations-peacekeepers-congo-drc

Gogali, L. TEDXUbud. “Indonesian Women’s Empowerment in a Post-Conflict Society.” (2011).

TED Talk about women’s active protection of the family, organizing across ethnic and religious lines, and grassroots involvement in the peace process in post-conflict Indonesia.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-i9unT9aZ8E

Hansson, J. & Hendriksson, Malin. “Western NGOs Representation of “Third World Women: A Comparative Study of Kvinna till Kvinna (Sweden) and Women for Women International (USA).” University West. (2016).

http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:632032/fulltext01.pdf

Heathcote, G. “Lecture: The Protection of Civilians and Protection of Peacekeeping Mandates: Gender and Ethics in Collective Security.” Feminists @ Law 5(2): (2015).

Critiques the UN Security Council Resolutions on Women, Peace and Security to illustrate how feminist ethics are used to justify new methods of violence.

http://journals.kent.ac.uk/index.php/feministsatlaw/article/view/236

Noisi, C. O. & Farrugia, M. “A Long Road Ahead: Integrating Gender Perspectives into Peacekeeping Operations.” OpenDemocracy. (2014).

Examines gender norms and perspectives that have led to gaps implementing UN Resolution 1325.

https://www.opendemocracy.net/open-security/chiara-oriti-niosi-maud-farrugia/long-road-ahead-integrating-gender-perspectives-into-

Restrepo, E. M. “Leaders Against All Odds: Women Victims of Conflict in Colombia.” Palgrave Communications 2, 1 – 11: (2016).

Highlights the capacity of women who have been victims of violence to be agents of peace and reconciliation.

http://www.palgrave-journals.com/articles/palcomms201614

Prenzler, T. & Sinclair, G. The Status of Women Police Officers: An International Review. International Journal of Law, Crime and Justice 41(2), 115 – 131: (2013).

Reports on a survey on the status of women police officers from 23 locations globally.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlcj.2012.12.001

United Nations Peacekeeping. “Gender and Peacekeeping.”

Main United Nations resource with further information on gender and peacekeeping.

http://www.un.org/en/peacekeeping/issues/women/