Introduction to Professional Communications by Melissa Ashman is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Introduction to Professional Communications by Melissa Ashman is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Introduction to Professional Communications was adapted and remixed by Melissa Ashman from several open textbooks as indicated at the end of each chapter. Unless otherwise noted, Introduction to Professional Communications is (c) 2018 by Melissa Ashman and is licensed under a Creative Commons-Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license.

In Introduction to Professional Communications, examples have been changed to Canadian references, and information throughout the book, as applicable, has been revised to reflect Canadian content and language. Gender neutral language (they/their) has been used intentionally. In addition, while general ideas and content may remain unchanged from the sources from which this adapted version is based, word choice, phrasing, and organization of content within each chapter may have changed to reflect this author’s stylistic preferences.

The following additions or changes have been made to these chapters:

Chapter 1.1

Chapter 2.1

Chapter 2.2

Chapter 2.4

Chapter 2.7

Chapter 3.1

Chapter 3.2

Chapter 4.1

Chapter 4.2

Chapter 4.3

Chapter 4.4

Chapter 4.5

Chapter 4.6

Chapter 4.7

Chapter 4.8

Chapter 4.9

Chapter 4.11

Chapter 5.5

Chapter 5.6

Chapter 6.1

Chapter 6.2

Chapter 7.1

Chapter 7.2

Chapter 7.3

You are free to use or modify (adapt) any of this material providing the terms of the Creative Commons licenses are adhered to.

If you adopt this book, as a core or supplemental resource, please report your adoption in order for us to celebrate your support of students’ savings. Report your commitment at www.openlibrary.ecampusontario.ca.

We invite you to adapt this book further to meet your and your students’ needs. Please let us know if you do! If you would like to use Pressbooks, the platform used to make this book, contact eCampusOntario for an account using open@ecampusontario.ca.

If this text does not meet your needs, please check out our full library at www.openlibrary.ecampusontario.ca. If you still cannot find what you are looking for, connect with colleagues and eCampusOntario to explore creating your own open education resource (OER).

eCampusOntario is a not-for-profit corporation funded by the Government of Ontario. It serves as a centre of excellence in online and technology-enabled learning for all publicly funded colleges and universities in Ontario and has embarked on a bold mission to widen access to post-secondary education and training in Ontario. This textbook is part of eCampusOntario’s open textbook library, which provides free learning resources in a wide range of subject areas. These open textbooks can be assigned by instructors for their classes and can be downloaded by learners to electronic devices or printed for a low cost by our printing partner, The University of Waterloo. These free and open educational resources are customizable to meet a wide range of learning needs, and we invite instructors to review and adopt the resources for use in their courses.

You are your own best ally when it comes to your writing. Keeping a positive frame of mind about your journey as a writer is not a cliché or simple, hollow advice. Your attitude toward writing can and does influence your written products. Even if writing has been a challenge for you, the fact that you are reading this sentence means you perceive the importance of this essential skill. This text and discussions to follow will help you improve your writing, and your positive attitude is part of your success strategy.

Reading is one step many writers point to as an integral step in learning to write effectively. You may like Harry Potter books or be a Twilight fan, but if you want to write effectively in business, you need to read business-related documents. These can include letters, reports, business proposals, and business plans. You may find these where you work or in your school’s writing centre, business department, or library; there are also many websites that provide sample business documents of all kinds. Your reading should also include publications in the industry where you work or plan to work. You can also gain an advantage by reading publications in fields other than your chosen one; often reading outside your niche can enhance your versatility and help you learn how other people express similar concepts. Finally, don’t neglect popular or general media like newspapers and magazines. Reading is one of the most useful lifelong habits you can practice to boost your business communication skills.

In the “real world” when you are under a deadline and production is paramount, you’ll be rushed and may lack the time to do adequate background reading for a particular assignment. For now, take advantage of your business communications course by exploring common business documents you may be called on to write, contribute to, or play a role in drafting in your future career. Some documents have a degree of formula to them, and your familiarity with them will reduce your preparation and production time while increasing your effectiveness.

When given a writing assignment, it is important to make sure you understand what you are being asked to do. You may read the directions and try to put them in your own words to make sense of the assignment. Be careful, however, to differentiate between what the directions say and what you think they say. Just as an audience’s expectations should be part of your consideration of how, what, and why to write, the instructions given by your instructor, or in a work situation by your supervisor, establish expectations. Just as you might ask a mentor more about a business writing assignment at work, you need to use the resources available to you to maximize your learning opportunity. Ask the professor to clarify any points you find confusing, or perceive more than one way to interpret, in order to better meet the expectations.

Learning to write effectively involves reading, writing, critical thinking, and self-reflection. At times, it may seem like it’s an incredibly messy process. Other times, it may feel tedious. Ultimately, writing is a process that takes time, effort, and practice. In the long-term, your skillful ability to craft messages will make a significant difference in your career.

This chapter contains material taken from Chapter 4.2 “How is writing learned” in Business Communication for Success and is used under a CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0 International license.

Think about communication in your daily life. When you make a phone call, send a text message, or like a post on Facebook, what is the purpose of that activity? Have you ever felt confused by what someone is telling you or argued over a misunderstood email? The underlying issue may very well be a communication deficiency.

There are many current models and theories that explain, plan, and predict communication processes and their successes or failures. In the workplace, we might be more concerned about practical knowledge and skills than theory. However, good practice is built on a solid foundation of understanding and skill.

The word communication is derived from a Latin word meaning “to share.” Communication can be defined as “purposefully and actively exchanging information between two or more people to convey or receive the intended meanings through a shared system of signs and (symbols)” (“Communication,” 2015, para. 1).

Let us break this definition down by way of example. Imagine you are in a coffee shop with a friend, and they are telling you a story about the first goal they scored in hockey as a child. What images come to mind as you hear their story? Is your friend using words you understand to describe the situation? Are they speaking in long, complicated sentences or short, descriptive sentences? Are they leaning back in their chair and speaking calmly, or can you tell they are excited? Are they using words to describe the events leading up to their big goal, or did they draw a diagram of the rink and positions of the players on a napkin? Did your friend pause and wait for you to to comment throughout their story or just blast right through? Did you have trouble hearing your friend at any point in the story because other people were talking or because the milk steamer in the coffee shop was whistling?

All of these questions directly relate to the considerations for communication in this course, including analyzing the audience, choosing a communications channel, using plain language, and using visual aids.

Before we examine each of these considerations in more detail, we should consider the elements of the communication process.

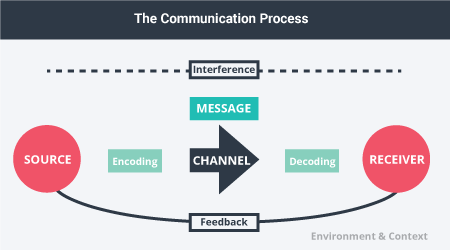

The communication process includes the steps we take in order to ensure we have succeeded in communicating. The communication process comprises essential and interconnected elements detailed in Fig. 1.2.1. We will continue to reflect on the story of your friend in the coffee shop to explore each element in detail.

Fig. 1.2.1 The communication process by Laura Underwood

Source: The source comes up with an idea and sends a message in order to share information with others. The source could be one other person or a group of people. In our example above, your friend is trying to share the events leading up to their first hockey goal and, likely, the feelings they had at the time as well.

Message: The message is the information or subject matter the source is intending to share. The information may be an opinion, feelings, instructions, requests, or suggestions. In our example above, your friend identified information worth sharing, maybe the size of one of the defence players on the other team, in order to help you visualize the situation.

Channels: The source may encode information in the form of words, images, sounds, body language, and more. There are many definitions and categories of communication channels to describe their role in the communication process, including verbal, non-verbal, written, and digital. In our example above, your friends might make sounds or use body language in addition to their words to emphasize specific bits of information. For example, when describing a large defense player on the other team, they may extend their arms to explain the height of the other team’s defense player.

Receiver: The receiver is the person for whom the message is intended. This person is charged with decoding the message in an attempt to understand the intentions of the source. In our example above, you as the receiver may understand the overall concept of your friend scoring a goal in hockey and can envision the techniques your friend used. However, there may also be some information you do not understand—such as a certain term—or perhaps your friend describes some events in a confusing order. One thing the receiver might try is to provide some kind of feedback to communicate back to the source that the communication did not achieve full understanding and that the source should try again.

Environment: The environment is the physical and psychological space in which the communication is happening (Mclean, 2005). It might also describe if the space is formal or informal. In our example above, it is the coffee shop you and your friend are visiting in.

Context: The context is the setting, scene, and psychological and psychosocial expectations of the source and the receiver(s) (McLean, 2005). This is strongly linked to expectations of those who are sending the message and those who are receiving the message. In our example above, you might expect natural pauses in your friend’s storytelling that will allow you to confirm your understanding or ask a question.

Interference: There are many kinds of interference (also called “noise”) that inhibit effective communication. Interference may include poor audio quality or too much sound, poor image quality, too much or too little light, attention, etc. In our working example, the coffee shop might be quite busy and thus very loud. You would have trouble hearing your friend clearly, which in turn might cause you to miss a critical word or phrase important to the story.

Those involved in the communication process move fluidly between each of these eight elements until the process ends.

Communication. (n.d.). In Wikipedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Communication.

McLean, S. (2005). The basics of interpersonal communication. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

This chapter is an adaptation of Part 1 (Foundations) in the Professional Communications OER by the Olds College OER Development Team and is used under a CC-BY 4.0 International license. You can download this book for free at http://www.procomoer.org/.

Although understanding is the foundation of all reading experiences, it is not the goal of most post-secondary reading assignments. Your professors want you to read critically, which means moving beyond what the text says to asking questions about the how and why of the text’s meaning.

Reading critically means reading skeptically, not accepting everything a text says at face value, and wondering why a particular author made a particular argument in a particular way.

When you read critically, you read not only to understand the meaning of the text, but also to question and analyze the text. You want to know not just what the text says, but also how and why it says what it says. Asking questions is one key strategy to help you read more critically. As you read a text critically, you are also reading skeptically.

A critical reader aims to answer two basic questions:

To answer “what is the author doing?” begin by carefully examining the following:

It may be helpful to try to see the argument from different angles:

To answer “how well is the author doing it?” consider the following questions:

Asking questions of a text helps readers:

The easiest way to develop questions about a text is to be aware of your thinking process before, during, and after reading.

As you approach your writing project, it is important to practice the habit of thinking critically. Critical thinking can be defined as “self-directed, self-disciplined, self-monitored, and self-corrective thinking” (Paul & Elder, 2007). It is the difference between watching television in a daze versus analyzing a movie with attention to its use of lighting, camera angles, and music to influence the audience. One activity requires very little mental effort, while the other requires attention to detail, the ability to compare and contrast, and sharp senses to receive all the stimuli.

As a habit of mind, critical thinking requires established standards and attention to their use, effective communication, problem solving, and a willingness to acknowledge and address our own tendency for confirmation bias. We’ll use the phrase “habit of mind” because clear, critical thinking is a habit that requires effort and persistence. People do not start an exercise program, a food and nutrition program, or a stop-smoking program with 100 percent success the first time. In the same way, it is easy to fall back into lazy mental short cuts, such as “If it costs a lot, it must be good,” when in fact the statement may very well be false. You won’t know until you gather information that supports (or contradicts) the assertion.

As we discuss getting into the right frame of mind for writing, keep in mind that the same recommendations apply to reading and research. If you only pay attention to information that reinforces your existing beliefs and ignore or discredit information that contradicts your beliefs, you are guilty of confirmation bias (Gilovich, 1993). As you read, research, and prepare for writing, make an effort to gather information from a range of reliable sources, whether or not this information leads to conclusions you didn’t expect. Remember that those who read your writing will be aware of, or have access to, this universe of data as well and will have their own confirmation bias. Reading and writing from an audience-centered view means acknowledging your confirmation bias and moving beyond it to consider multiple frames of references, points of view, and perspectives as you read, research, and write. False thinking strategies can lead to poor conclusions, so be sure to watch out for your tendency to read, write, and believe that which reflects only what you think you know without solid research and clear, critical thinking.

Gilovich, T. (1993). How we know what isn’t so: The fallibility of human reason in everyday life. New York, NY: The Free Press.

Paul, R., & Elder, L. (2007). The miniature guide to critical thinking: Concepts and tools. Dillon Beach, CA: The Foundation for Critical Thinking Press.

This chapter contains material taken from “Critical thinking”; “Overview 3”; and “Reading critically” in Developmental Writing by Lumen Learning (used under a CC-BY 3.0 license) and Chapter 5.1 “Think, then write: Writing preparation” in Business Communication for Success (used under a CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0 International license).

Communication is a complex process, and it is difficult to determine where or with whom a communication encounter starts and ends. Models of communication simplify the process by providing a visual representation of the various aspects of a communication encounter. Some models explain communication in more detail than others, but even the most complex model still doesn’t recreate what we experience in even a moment of a communication encounter. Models still serve a valuable purpose for students of communication because they allow us to see specific concepts and steps within the process of communication, define communication, and apply communication concepts. When you become aware of how communication functions, you can think more deliberately through your communication encounters, which can help you better prepare for future communication and learn from your previous communication. The three models of communication we will discuss are the transmission, interaction, and transaction models.

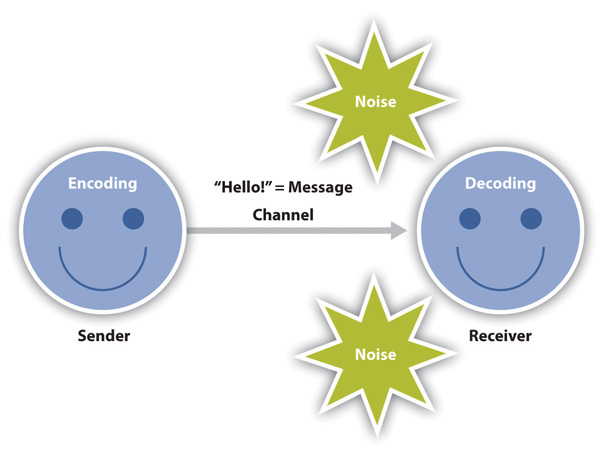

Although these models of communication differ, they contain some common elements. The first two models we will discuss, the transmission model and the interaction model, include the following parts: participants, messages, encoding, decoding, and channels. In communication models, the participants are the senders and/or receivers of messages in a communication encounter. The message is the verbal or nonverbal content being conveyed from sender to receiver. For example, when you say “Hello!” to your friend, you are sending a message of greeting that will be received by your friend.

The internal cognitive process that allows participants to send, receive, and understand messages is the encoding and decoding process. Encoding is the process of turning thoughts into communication. As we will learn later, the level of conscious thought that goes into encoding messages varies. Decoding is the process of turning communication into thoughts. For example, you may realize you’re hungry and encode the following message to send to your roommate: “I’m hungry. Do you want to get pizza tonight?” As your roommate receives the message, they decode your communication and turn it back into thoughts in order to make meaning out of it. Of course, we don’t just communicate verbally—we have various options, or channels for communication. Encoded messages are sent through a channel, or a sensory route on which a message travels, to the receiver for decoding. While communication can be sent and received using any sensory route (sight, smell, touch, taste, or sound), most communication occurs through visual (sight) and/or auditory (sound) channels. If your roommate has headphones on and is engrossed in a video game, you may need to get their attention by waving your hands before you can ask them about dinner.

The linear or transmission model of communication, as shown in Figure 2.2.1, describes communication as a linear, one-way process in which a sender intentionally transmits a message to a receiver (Ellis & McClintock, 1990). This model focuses on the sender and message within a communication encounter. Although the receiver is included in the model, this role is viewed as more of a target or end point rather than part of an ongoing process. We are left to presume that the receiver either successfully receives and understands the message or does not. The scholars who designed this model extended on a linear model proposed by Aristotle centuries before that included a speaker, message, and hearer. They were also influenced by the advent and spread of new communication technologies of the time such as telegraphy and radio, and you can probably see these technical influences within the model (Shannon & Weaver, 1949). Think of how a radio message is sent from a person in the radio studio to you listening in your car. The sender is the radio announcer who encodes a verbal message that is transmitted by a radio tower through electromagnetic waves (the channel) and eventually reaches your (the receiver’s) ears via an antenna and speakers in order to be decoded. The radio announcer doesn’t really know if you receive their message or not, but if the equipment is working and the channel is free of static, then there is a good chance that the message was successfully received.

Figure 2.2.1 The linear model of communication

Although the transmission model may seem simple or even underdeveloped to us today, the creation of this model allowed scholars to examine the communication process in new ways, which eventually led to more complex models and theories of communication.

The interactive or interaction model of communication, as shown in Figure 2.2.2, describes communication as a process in which participants alternate positions as sender and receiver and generate meaning by sending messages and receiving feedback within physical and psychological contexts (Schramm, 1997). Rather than illustrating communication as a linear, one-way process, the interactive model incorporates feedback, which makes communication a more interactive, two-way process. Feedback includes messages sent in response to other messages. For example, your instructor may respond to a point you raise during class discussion or you may point to the sofa when your roommate asks you where the remote control is. The inclusion of a feedback loop also leads to a more complex understanding of the roles of participants in a communication encounter. Rather than having one sender, one message, and one receiver, this model has two sender-receivers who exchange messages. Each participant alternates roles as sender and receiver in order to keep a communication encounter going. Although this seems like a perceptible and deliberate process, we alternate between the roles of sender and receiver very quickly and often without conscious thought.

The interactive model is also less message focused and more interaction focused. While the linear model focused on how a message was transmitted and whether or not it was received, the interactive model is more concerned with the communication process itself. In fact, this model acknowledges that there are so many messages being sent at one time that many of them may not even be received. Some messages are also unintentionally sent. Therefore, communication isn’t judged effective or ineffective in this model based on whether or not a single message was successfully transmitted and received.

Figure 2.2.2 The interactive model of communication

The interactive model takes physical and psychological context into account. Physical context includes the environmental factors in a communication encounter. The size, layout, temperature, and lighting of a space influence our communication. Imagine the different physical contexts in which job interviews take place and how that may affect your communication. I have had job interviews over the phone, crowded around a table with eight interviewers, and sitting with few people around an extra large conference table. I’ve also been walked around an office to unexpectedly interview one-on-one, in succession, with multiple members of a search committee over a period of three hours. Whether it’s the size of the room or other environmental factors, it’s important to consider the role that physical context plays in our communication. Psychological context includes the mental and emotional factors in a communication encounter. Stress, anxiety, and emotions are just some examples of psychological influences that can affect our communication. Seemingly positive psychological states, like experiencing the emotion of love, can also affect communication. Feedback and context help make the interaction model a more useful illustration of the communication process, but the transaction model views communication as a powerful tool that shapes our realities beyond individual communication encounters.

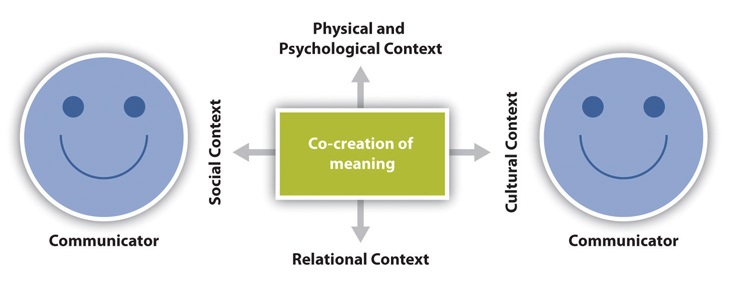

As the study of communication progressed, models expanded to account for more of the communication process. Many scholars view communication as more than a process that is used to carry on conversations and convey meaning. We don’t send messages like computers, and we don’t neatly alternate between the roles of sender and receiver as an interaction unfolds. We also can’t consciously decide to stop communicating because communication is more than sending and receiving messages. The transaction model differs from the transmission and interaction models in significant ways, including the conceptualization of communication, the role of sender and receiver, and the role of context (Barnlund, 1970).

The transaction model of communication describes communication as a process in which communicators generate social realities within social, relational, and cultural contexts. In this model, which is shown in Figure 2.2.3, we don’t just communicate to exchange messages; we communicate to create relationships, form intercultural alliances, shape our self-concepts, and engage with others in dialogue to create communities.

The roles of sender and receiver in the transaction model of communication differ significantly from the other models. Instead of labeling participants as senders and receivers, the people in a communication encounter are referred to as communicators. Unlike the interactive model, which suggests that participants alternate positions as sender and receiver, the transaction model suggests that we are simultaneously senders and receivers. This is an important addition to the model because it allows us to understand how we are able to adapt our communication—for example, a verbal message—in the middle of sending it based on the communication we are simultaneously receiving from our communication partner.

Figure 2.2.3 The transaction model of communication

The transaction model also includes a more complex understanding of context. The interaction model portrays context as physical and psychological influences that enhance or impede communication. While these contexts are important, they focus on message transmission and reception. Since the transaction model of communication views communication as a force that shapes our realities before and after specific interactions occur, it must account for contextual influences outside of a single interaction. To do this, the transaction model considers how social, relational, and cultural contexts frame and influence our communication encounters.

Social context refers to the stated rules or unstated norms that guide communication. Norms are social conventions that we pick up on through observation, practice, and trial and error. We may not even know we are breaking a social norm until we notice people looking at us strangely or someone corrects or teases us. Relational context includes the previous interpersonal history and type of relationship we have with a person. We communicate differently with someone we just met versus someone we’ve known for a long time. Initial interactions with people tend to be more highly scripted and governed by established norms and rules, but when we have an established relational context, we may be able to bend or break social norms and rules more easily. Cultural context includes various aspects of identities such as race, gender, nationality, ethnicity, sexual orientation, class, and ability. We all have multiple cultural identities that influence our communication. Some people, especially those with identities that have been historically marginalized, are regularly aware of how their cultural identities influence their communication and influence how others communicate with them. Conversely, people with identities that are dominant or in the majority may rarely, if ever, think about the role their cultural identities play in their communication. Cultural context is influenced by numerous aspects of our identities and is not limited to race or ethnicity.

Barnlund, D. C. (1970). A transactional model of communication in K.K. Sereno and C.D. Mortenson (Eds.), Foundations of communication theory (pp. 83-92). New York, NY: Harper and Row.

Ellis, R. and McClintock, A. (1990). You take my meaning: Theory into practice in human communication. London: Edward Arnold.

Schramm, W. (1997). The beginnings of communication study in America. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Shannon, C. and Weaver, W. (1949). The mathematical theory of communication. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

This chapter contains material taken from Chapter 1.2 “The communication process” in Communication in the real world: An introduction to communication studies and is used under a CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0 International license.

Throughout the next few chapters, we will examine these various steps in greater detail.

The audience any piece of writing is the intended or potential reader or readers. This should be the most important consideration in planning, writing, and reviewing a document. You “adapt” your writing to meet the needs, interests, and background of the readers who will be reading your writing.

The principle seems absurdly simple and obvious. It’s much the same as telling someone, “Talk so the person in front of you can understand what you’re saying.” It’s like saying, “Don’t talk rocket science to your six-year-old.” Do we need a course in that? Doesn’t seem like it. But, in fact, lack of audience analysis and adaptation is one of the root causes of most of the problems you find in business documents.

Audiences, regardless of category, must also be analyzed in terms of characteristics such as the following:

Audience analysis can get complicated by other factors, such as mixed audience types for one document and wide variability within the audience.

Thill, J. V., & Bovee, C. L. (2004). Business communication today (8th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

This chapter contains material taken from Chapter 5.2 “A planning checklist for business messages” in Business Communication for Success (used under a CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0 International license) and “Audience analysis” in the Online Technical Writing Textbook by D. McMurray (used under a CC-BY 4.0 International license).

Preparation for the writing process involves purpose, research and investigation, reading and analyzing, and adaptation. In this chapter, we consider how to determine the purpose of a document and how that awareness guides the writer to effective product.

While you may be free to create documents that represent yourself or your organization, your employer will often have direct input into their purpose. All acts of communication have general and specific purposes, and the degree to which you can identify these purposes will influence how effective your writing is. General purposes involve the overall goal of the communication interaction, which have been mentioned previously: to inform, persuade, entertain, facilitate interaction, or motivate a reader. The general purpose influences the presentation and expectation for feedback. In an informative message—the most common type of writing in business—you will need to cover several predictable elements:

Some elements may receive more attention than others, and they do not necessarily have to be addressed in the order you see here. Depending on the nature of your project, as a writer you will have a degree of input over how you organize them.

Note that the last item, Why, is designated as optional. This is because business writing sometimes needs to report facts and data objectively, without making any interpretation or pointing to any cause-effect relationship. In other business situations, of course, identifying why something happened or why a certain decision is advantageous will be the essence of the communication.

In addition to its general purpose (e.g., to inform, persuade, entertain, or motivate), every piece of writing also has at least one specific purpose, which is the intended outcome–the result that will happen once your written communication has been read.

For example, imagine that you are an employee in a small city’s housing authority and have been asked to draft a letter to city residents about radon. Radon is a naturally occurring radioactive gas that has been classified by Health Canada as a health hazard. In the course of a routine test, radon was detected in minimal levels in an apartment building operated by the housing authority. It presents a relatively low level of risk, but because the incident was reported in the local newspaper, the mayor has asked the housing authority director to be proactive in informing all the city residents of the situation.

The general purpose of your letter is to inform, and the specific purpose is to have a written record of informing all city residents about how much radon was found, when, and where; where they can get more information on radon; and the date, time, and place of the meeting. Residents may read the information and attend or they may not even read the letter. But once the letter has been written, signed, and distributed, your general and specific purposes have been accomplished.

Now imagine that you begin to plan your letter by applying the above list of elements. Recall that the letter informs residents on three counts: (1) the radon finding, (2) where to get information about radon, and (3) the upcoming meeting. For each of these pieces of information, the elements may look like the following:

Radon Finding

Information about radon

City meeting about radon

Once you have laid out these elements of your informative letter, you have an outline from which it will be easy to write the actual letter.

Your effort serves as a written record of correspondence informing them that radon was detected, which may be one of the specific or primary purposes. A secondary purpose may be to increase attendance at the town hall meeting, but you will need feedback from that event to determine the effectiveness of your effort.

Now imagine that instead of being a housing authority employee, you are a city resident who receives that informative letter, and you happen to operate a business as a certified radon mitigation contractor. You may decide to build on this information and develop a persuasive message. You may draft a letter to the homeowners and landlords in the neighborhood near the building in question. To make your message persuasive, you may focus on the perception that radiation is inherently dangerous and that no amount of radon has been declared safe. You may cite external authorities that indicate radon is a contributing factor to several health ailments, and even appeal to emotions with phrases like “protect your children” and “peace of mind.” Your letter will probably encourage readers to check with Health Canada to verify that you are a certified contractor, describe the services you provide, and indicate that friendly payment terms can be arranged.

At this point in the discussion, we need to visit the concept of credibility. Credibility, or the perception of integrity of the message based on an association with the source, is central to any communication act. If the audience perceives the letter as having presented the information in an impartial and objective way, perceives the health inspector’s expertise in the field as relevant to the topic, and generally regards the housing authority in a positive light, they will be likely to accept your information as accurate. If, however, the audience does not associate trust and reliability with your message in particular and the city government in general, you may anticipate a lively discussion at the city hall meeting.

In the same way, if the reading audience perceives the radon mitigation contractor’s letter as a poor sales pitch without their best interest or safety in mind, they may not respond positively to its message and be unlikely to contact him about any possible radon problems in their homes. If, however, the sales letter squarely addresses the needs of the audience and effectively persuades them, the contractor may look forward to a busy season.

Returning to the original housing authority scenario, did you consider how your letter might be received or the fear it may have generated in the audience? In real life you don’t get a second chance, but in our academic setting, we can go back and take more time on our assignment, using the twelve-item checklist presented in chapter 2.3. Imagine that you are the mayor or the housing authority director. Before you assign an employee to send a letter to inform residents about the radon finding, take a moment to consider how realistic your purpose is. As a city official, you may want the letter to serve as a record that residents were informed of the radon finding, but will that be the only outcome? Will people be even more concerned in response to the letter than they were when the item was published in the newspaper? Would a persuasive letter serve the city’s purposes better than an informative one?

Another consideration is the timing. On the one hand, it may be important to get the letter sent as quickly as possible, as the newspaper report may have already aroused concerns that the letter will help calm. On the other hand, given that the radon was discovered in mid-December, many people may be caught up in holiday celebrations and will not pay attention to the letter. In early January, everyone will be paying more attention to their mail as they anticipate the arrival of tax-related documents or even the dreaded credit card statement. If the mayor has scheduled the city hall meeting for January 7, people may be unhappy if they only learn about the meeting at the last minute. Also consider your staff; if many of them will be taking vacation during this period, there may not be enough staff in place to respond to phone calls that will likely come in response to the letter, even though the letter advises residents to contact Health Canada.

Next, how credible are the sources cited in the letter? If you as a housing authority employee have been asked to draft it, to whom should it go once you have it written? The city health inspector is mentioned as a source; will they read and approve the letter before it is sent? Is there someone at the region, provincial, or federal level who can, or should, check the information before it is sent?

The next item on the checklist is to make sure the message reflects positively on your business. In our hypothetical case, the “business” is city government. The letter should acknowledge that city officials and employees are servants of the taxpayers. “We are here to serve you” should be expressed, if not in so many words, in the tone of the letter.

The next three items on the checklist are associated with the audience profile: audience size, composition, knowledge, and awareness of the topic. Since your letter is being sent to all city residents, you likely have a database from which you can easily tell how many readers constitute your audience. What about audience composition? What else do you know about the city’s residents? What percentage of households includes children? What is the education level of most of the residents? Are there many residents whose first language is not English; if so, should your letter be translated into any other languages? What is the range of income levels in the city? How well informed are city residents about radon? Has radon been an issue in any other buildings in the city in recent years? The answers to these questions will help determine how detailed the information in your letter should be.

Finally, anticipate probable responses. Although the letter is intended to inform, could it be misinterpreted as an attempt to “cover up” an unacceptable condition in city housing? If the local newspaper were to reprint the letter, would the mayor be upset? Is there someone in public relations who will be doing media interviews at the same time the letter goes out? Will the release of information be coordinated, and if so by whom?

One additional point that deserves mention is the notion of decision makers. Even if your overall goal is to inform or persuade, the basic mission is to simply communicate. Establishing a connection is a fundamental aspect of the communication audience, and if you can correctly target key decision makers you increase your odds for making the connection with those you intend to inform or persuade. Who will open the mail or email? Who will act upon it? The better you can answer those questions, the more precise you can be in your writing efforts.

Government of Canada. (2017). Radon: What you need to know. Retrieved from https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/environmental-workplace-health/radiation/radon.html.

This chapter contains material taken from Chapter 5.2 “Think, then write: Writing preparation” in Business Communication for Success and is used under a CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0 International license.

Purpose is closely associated with channel. We need to consider the purpose when choosing a channel. From source to receiver, message to channel, feedback to context, environment, and interference, all eight components play a role in the dynamic process. While writing often focuses on an understanding of the receiver (as we’ve discussed) and defining the purpose of the message, the channel—or the “how” in the communication process—deserves special mention.

So far, we have discussed a simple and traditional channel of written communication: the hard-copy letter mailed in a standard business envelope and sent by postal mail. But in today’s business environment, this channel is becoming increasingly rare as electronic channels become more widely available and accepted.

When is it appropriate to send an instant message or text message versus a conventional e-mail or fax? What is the difference between a letter and a memo? Between a report and a proposal? Writing itself is the communication medium, but each of these specific channels has its own strengths, weaknesses, and understood expectations that are summarized in Table 2.5.1.

| Channel | Strengths | Weaknesses | Expectations | When to choose |

| Instant message or text message | Very fastGood for rapid exchanges of small amounts of information Inexpensive | InformalNot suitable for large amounts of information Abbreviations lead to misunderstandings | Quick response | Informal use among peers at similar levels within an organizationYou need a fast, inexpensive connection with a colleague over a small issue and limited amount of information |

| Channel | Strengths | Weaknesses | Expectations | When to choose |

| FastGood for relatively fast exchanges of information “Subject” line allows compilation of many messages on one subject or project Easy to distribute to multiple recipients Inexpensive | May hit “send” prematurelyMay be overlooked or deleted without being read “Reply to all” error “Forward” error Large attachments may cause the e-mail to be caught in recipient’s spam filter | Normally a response is expected within 24 hours, although norms vary by situation and organizational culture | You need to communicate but time is not the most important considerationYou need to send attachments (provided their file size is not too big) | |

| Channel | Strengths | Weaknesses | Expectations | When to choose |

| Fax | FastProvides documentation | Receiving issues (e.g., the receiving machine may be out of paper or toner)Long distance telephone charges apply Transitional telephone-based technology losing popularity to online information exchange | Normally, a long (multiple page) fax is not expected | You want to send a document whose format must remain intact as presented, such as a medical prescription or a signed work orderAllows use of letterhead to represent your company |

| Channel | Strengths | Weaknesses | Expectations | When to choose |

| Memo | Official but less formal than a letterClearly shows who sent it, when, and to whom | Memos sent through e-mails can get deleted without reviewAttachments can get removed by spam filters | Normally used internally in an organization to communicate directives from management on policy and procedure, or documentation | You need to communicate a general message within your organization |

| Channel | Strengths | Weaknesses | Expectations | When to choose |

| Letter | FormalLetterhead represents your company and adds credibility | May get filed or thrown away unreadCost and time involved in printing, stuffing, sealing, affixing postage, and travel through the postal system | Specific formats associated with specific purposes | You need to inform, persuade, deliver bad news or negative message, and document the communication |

| Channel | Strengths | Weaknesses | Expectations | When to choose |

| Report | Can require significant time for preparation and production | Requires extensive research and documentation | Specific formats for specific purposes | You need to document the relationship(s) between large amounts of data to inform an internal or external audience |

| Channel | Strengths | Weaknesses | Expectations | When to choose |

| Proposal | Can require significant time for preparation and production | Requires extensive research and documentation | Specific formats for specific purposes | You need to persuade an audience with complex arguments and data |

By choosing the correct channel for a message, you can save yourself many headaches and increase the likelihood that your writing will be read, understood, and acted upon in the manner you intended.

In terms of writing preparation, you should review any electronic communication before you send it. Spelling and grammatical errors will negatively impact your credibility. With written documents, we often take time and care to get it right the first time, but the speed of instant messaging, text messaging, or emailing often deletes this important review cycle of written works. Just because the document you prepare in a text message is only one sentence long doesn’t mean it can’t be misunderstood or expose you to liability. Take time when preparing your written messages, regardless of their intended presentation, and review your work before you click “send.”

This chapter is an adaptation of Chapter 5.2 “Think, then write: Writing preparation” in Business Communication for Success and is used under a CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0 International license.

Your audience is the person or people you want to communicate with. By knowing more about them (their wants, needs, values, etc.), you are able to better craft your message so that they will receive it the way you intended.

Your success as a communicator partly depends on how well you can tailor your message to your audience.

Your primary audience is your intended audience; it is the person or people you have in mind when you decide to communicate something. However, when analyzing your audience you must also beware of your secondary audience. These are other people you could reasonably expect to come in contact with your message. For example, you might send an email to a customer, who, in this case, is your primary audience, and copy (cc:) your boss, who would be your secondary audience. Beyond these two audiences, you also have to consider your hidden audience, which are people who you may not have intended to come in contact with your audience (or message) at all, such as a colleague who gets a forwarded copy of your email.

This chapter is an adaptation of Part 1: Foundations in the Professional Communications OER by the Olds College OER Development Team and is used under a CC-BY 4.0 International license. You can download this book for free at http://www.procomoer.org/.

There are social and economic characteristics that can influence how someone behaves as an individual. Standard demographic variables include a person’s age, gender, family status, education, occupation, income, and ethnicity. Each of these variables or characteristics can provide clues about how a person might respond to a message.

For example, people of different ages consume (use) media and social media differently. According to the Pew Research Center (2018), 81% of people aged 18-29 use Facebook, 64% use Instagram, and 40% use Twitter. In contrast, 65% of people aged 50-64 use Facebook, 21% use Instagram, and 19% use Twitter (Pew Research Center, 2018). If I were trying to market my product to those aged 50-64, I would likely reach a larger audience (and potentially make more sales) if I used targeted ads on Facebook rather than recruiting brand ambassadors on Instagram. Knowing the age (or ages) of your audience(s) can help inform what channels you use to send your message. It can also help you determine the best way to structure and tailor your message to meet specific audience characteristics.

Pew Research Center. (2018). Social media fact sheet. Retrieved from http://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheet/social-media/.

This chapter contains material taken from Chapter 4.5 “Audience segments: Demographics” in Information Strategies for Communicators by K. Hansen and N. Paul and is used under CC-BY 4.0 International license.

We all understand geographically defined political jurisdictions such as cities, provinces, and territories. You can also geographically segment audiences into rural, urban, suburban, and edge communities (the office parks that have sprung up on the outskirts of many urban communities). These geographic categories help define rifts between regions on issues such as transportation, education, taxes, housing, land use, and more. These are important geographic audience categories for politicians, marketers, and businesses. For example, local retail advertisers want to reach audiences who are in the reading or listening range of the local newspaper or radio station and within traveling distance of their stores. Therefore, it’s important to consider the geographic characteristics of your audience when crafting business messages.

This chapter is an adaptation of Chapter 4.6 “Audience segments: Geographics” in Information Strategies for Communicators by K. Hansen and N. Paul and is used under CC-BY 4.0 International license.

Psychographics refer to all the psychological variables that combine to form a person’s inner self. Even if two people share the same demographic or geographic characteristics, they may still hold entirely different ideas and values that define them personally and socially. Some of these differences are explained by looking at the psychographic characteristics that define them. Psychographic variables include:

Motives – an internal force that stimulates someone to behave in a particular manner. A person has media consumption motives and buying motives. A motive for watching television may be to escape; a motive for choosing to watch a situation comedy rather than a police drama may be the audience member’s need to laugh rather than feel suspense and anxiety.

Attitudes – a learned predisposition, a feeling held toward an object, person, or idea that leads to a particular behaviour. Attitudes are enduring; they are positive or negative, affecting likes and dislikes. A strong positive attitude can make someone very loyal to a brand (one person is committed to the Mazda brand so they will only consider Mazda models when it is time to buy a new car). A strong negative attitude can turn an audience member away from a message or product (someone disagrees with the political slant of Fox News and decides to watch MSNBC instead).

Personalities – a collection of traits that make a person distinctive. Personalities influence how people look at the world, how they perceive and interpret what is happening around them, how they respond intellectually and emotionally, and how they form opinions and attitudes.

Lifestyles – these factors form the mainstay of psychographic research. Lifestyle research studies the way people allocate time, energy and money.

This chapter is an adaptation of Chapter 4.7 “Audience segments: Psychographics” in Information Strategies for Communicators by K. Hansen and N. Paul and is used under CC-BY 4.0 International license.

Let’s say you’ve analyzed your audience until you know them better than you know yourself. What good is it? How do you use this information? How do you keep from writing something that will still be incomprehensible or useless to your readers?

The business of writing to your audience may have a lot to do with in-born talent, intuition, and even mystery. But there are some controls you can use to have a better chance to connect with your readers. The following “controls” mostly have to do with making information more understandable for your specific audience:

These are the kinds of “controls” that you can use to fine-tune your messages and make them as readily understandable as possible. In contrast, it’s the accumulation of lots of problems in these areas—even seemingly trivial ones—that add up to a document being difficult to read and understand.

This chapter is an adaptation of “Audience analysis” in the Online Technical Writing Textbook by D. McMurray and is used under a CC-BY 4.0 International license.

Writing style is the manner in which a writer addresses the reader. It involves qualities of writing such as vocabulary and figures of speech, phrasing, rhythm, sentence structure, and paragraph length. Developing an appropriate business writing style will reflect well on you and increase your success in any career. Misspellings of individual words or grammatical errors involving misplacement or incorrect word choices in a sentence can create confusion, lose meaning, and have a negative impact on the reception of your document. Errors themselves are not inherently bad, but failure to recognize and fix them will reflect on you, your company, and limit your success. Self-correction is part of the writing process.

Informal and formal are two common styles that carry their own particular sets of expectations. Which style you use will depend on your audience and the purpose of the document.

Informal style is a casual style of writing. It differs from standard business English in that it often makes use of colourful expressions, slang, and regional phrases. As a result, it can be difficult to understand for an English learner or a person from a different region of the country. Sometimes colloquialism takes the form of a word difference; for example, the difference between a “Coke,” a “tonic,” a “pop,” and a “soda pop” primarily depends on where you live.

This type of writing uses colloquial language, such as the style of writing that is often used in texting:

ok fwiw i did my part n put it in where you asked but my ? is if the group does not participate do i still get credit for my part of what i did n also how much do we all have to do i mean i put in my opinion of the items in order do i also have to reply to the other team members or what? Thxs

While we may be able to grasp the meaning of the message and understand some of the abbreviations, this informal style is generally not appropriate in business communications. That said, colloquial writing may be permissible, and even preferable, in some limited business contexts. For example, a marketing letter describing a folksy product such as a wood stove or an old-fashioned popcorn popper might use a colloquial style to create a feeling of relaxing at home with loved ones. Still, it is important to consider how colloquial language will appear to the audience. Will the meaning of your chosen words be clear to a reader who is from a different part of the country? Will a folksy tone sound like you are “talking down” to your audience, assuming that they are not intelligent or educated enough to appreciate standard English? A final point to remember is that colloquial style is not an excuse for using expressions that are sexist, racist, profane, or otherwise offensive.

In business writing, often the appropriate style will have a degree of formality. Writers using a formal style tend to use a more sophisticated vocabulary—a greater variety of words, and more words with multiple syllables—not for the purpose of throwing big words around, but to enhance the formal mood of the document. They also tend to use more complex syntax, resulting in sentences that are longer and contain more subordinate clauses. That said, it’s still critically important to ensure the words you use are precise, relevant, and convey the appropriate and accurate meaning! This writing style may use the third person and may also avoid using contractions. However, this isn’t always the case.

If you answered “it depends,” you are correct.

Audiences have expectations and your job is to meet them. Some business audiences prefer a fairly formal tone. If you include contractions or use a style that is too casual, you may lose their interest and attention; you may also give them a negative impression of your level of expertise. However, if you are writing for an audience that expects informal language, you may lose their interest and attention by writing too formally; your writing may also come across as arrogant or pompous. It is not that one style is better than the other, but simply that styles of writing vary across a range of options. The skilled business writer will know their audience and will adapt the message to best facilitate communication. Choosing the right style can make a significant impact on how your writing is received.

If you use expressions that imply a relationship or a special awareness of information such as “you know,” or “as we discussed,” without explaining the necessary background, your writing may be seen as overly familiar, intimate, or even secretive. Trust is the foundation for all communication interactions and a careless word or phrase can impair trust.

If you want to use humour, think carefully about how your audience will interpret it. Humour is a fragile form of communication that requires an awareness of irony, of juxtaposition, or a shared sense of attitudes, beliefs, and values. Different people find humour in different situations, and what is funny to one person may be dull, or even hurtful, to someone else.

This chapter contains material taken from Chapter 4.4 “Style in written communication” and Chapter 6.2 “Writing style” in Business Communication for Success and is used under a CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0 International license.

While there was a time when many business documents were written in the third person to give them the impression of objectivity, this formal style was often passive and wordy. Today, it has given way to active, clear, concise writing, sometimes known as “plain English” (Bailey, 2008). Plain language style involves everyday words and expressions in a familiar group context and may include contractions. Why use a $100 word when a 25 cent one will do?

As business and industry increasingly trade across borders and languages, writing techniques that obscure meaning or impede understanding can cause serious problems. Efficient writing styles have become the norm.

No matter who your audience is, they will appreciate your ability to write using plain language. Here are five principles for writing in plain language:

To communicate professionally, you need to know when and how to use either active or passive voice. Although most contexts prefer the active voice, the passive voice may be the best choice in certain situations. Generally, though, passive voice tends to be awkward, vague, wordy, and a grammatical construct you should avoid in most cases.

To use active voice, make the noun that performs the action the subject of the sentence and pair it directly with an action verb.

Read these two sentences:

Matt Damon left Harvard in the late 1980s to start his acting career.

Matt Damon’s acting career was started in the late 1980s when he left Harvard.

In the first sentence, left is an action verb that is paired with the subject, Matt Damon. If you ask yourself, “Who or what left?” the answer is Matt Damon. Neither of the other two nouns in the sentence—Harvard and career—“left” anything.

Now look at the second sentence. The action verb is started. If you ask yourself, “Who or what started something?” the answer, again, is Matt Damon. But in this sentence, the writer placed career—not Matt Damon—in the subject position. When the doer of the action is not the subject, the sentence is in passive voice. In passive voice constructions, the doer of the action usually follows the word by as the indirect object of a prepositional phrase, and the action verb is typically partnered with a version of the verb to be.

Writing in active voice is easy once you understand the difference between active and passive voice. Make sure you always define who or what did what.

While using the active voice is preferred, sometimes passive voice is the best option. Consider the following acceptable uses of passive voice.

Example: Our front-door lock was picked.

Rationale: If you do not know who picked the lock on your front door, you cannot say who did it. You could say a thief broke in, but that would be an assumption; you could, theoretically, find out that the lock was picked by a family member who had forgotten to take a key.

Example: The basement was filled with a mysterious scraping sound.

Rationale: If you are writing a dramatic story, you might introduce a phenomenon without revealing the person or thing that caused it.

Example: The park was flooded all week.

Rationale: Although you would obviously know that the rainwater flooded the park, saying so would not be important.

Example: A mistake was made in the investigation that resulted in the wrong person being on trial.

Rationale: Even if you think you know who is responsible for a problem, you might not want to expose the person.

Example: It was noted that only first-graders chose to eat the fruit.

Rationale: Research reports in certain academic disciplines attempt to remove the researcher from the results, to avoid saying, for example, “I noted that only first graders….”

Example: If the password is forgotten by the user, a security question will be asked.

Rationale: This construction avoids the need for the cumbersome “his or her” (as in “the user forgets his or her password”).

Inappropriate word choices will get in the way of your message. For this reason, use language that is accurate and appropriate for the writing situation. Omit jargon (technical words and phrases common to a specific profession or discipline) and slang (invented words and phrases specific to a certain group of people), unless your audience and purpose call for such language. Avoid using outdated words and phrases, such as “Dial the number.” Be straightforward in your writing rather than using euphemisms (gentler, but sometimes inaccurate, ways of saying something). Be clear about the level of formality each piece of writing needs, and adhere to that level.

Jargon and slang both have their places. Using jargon is fine as long as you can safely assume your readers also know the jargon. For example, if you are a lawyer writing to others in the legal profession, using legal jargon is perfectly fine. On the other hand, if you are writing for people outside the legal profession, using legal jargon would most likely be confusing, and you should avoid it. Of course, lawyers must use legal jargon in papers they prepare for customers. However, those papers are designed to navigate within the legal system and may not be clear to readers outside of this demographic.

Unless there is a specific reason not to, use positive language wherever you can. Positive language benefits your writing in two ways. First, it creates a positive tone, and your writing is more likely to be well-received. Second, it clarifies your meaning, as positive statements are more concise. Take a look at the following negatively worded sentences and then their positive counterparts, below.

Examples: Negative: Your car will not be ready for collection until Friday. Negative: You did not complete the exam. Negative: Your holiday time is not approved until your manager clears it. |

Avoid using multiple negatives in one sentence, as this will make your sentence difficult to understand. When readers encounter more than one negative construct in a sentence, their brains have to do more cognitive work to decipher the meaning; multiple negatives can create convoluted sentences that bog the reader down.

Examples: Negative: A decision will not be made unless all board members agree. Negative: The event cannot be scheduled without a venue. |

When you write for your readers and speak to an audience, you have to consider who they are and what they need to know. When readers know that you are concerned with their needs, they are more likely to be receptive to your message, and will be more likely to take the action you are asking them to and focus on important details.

Your message will mean more to your reader if they get the impression that it was written directly to them.

When you write, ask yourself, “Why would someone read this message?” Often, it is because the reader needs a question answered. What do they need to know to prepare for the upcoming meeting, for example, or what new company policies do they need to abide by? Think about the questions your readers will ask and then organize your document to answer them.

It is easy to let your sentences become cluttered with words that do not add value to your message. Improve cluttered sentences by eliminating repetitive ideas, removing repeated words, and editing to eliminate unnecessary words.

Unless you are providing definitions on purpose, stating one idea twice in a single sentence is redundant.

As a general rule, you should try not to repeat a word within a sentence. Sometimes you simply need to choose a different word, but often you can actually remove repeated words.

Example: Original: The student who won the cooking contest is a very talented and ambitious student. Revision: The student who won the cooking contest is very talented and ambitious. |

If a sentence has words that are not necessary to carry the meaning, those words are unneeded and can be removed.

Examples: Original: Andy has the ability to make the most fabulous twice-baked potatoes. Revision: Andy makes the most fabulous twice-baked potatoes. Original: For his part in the cooking class group project, Malik was responsible for making the mustard reduction sauce. Revision: Malik made the mustard reduction sauce for his cooking class group project. |

Many people create needlessly wordy sentences using expletive pronouns, which often take the form of “There is …” or “There are ….”

Pronouns (e.g., I, you, he, she, they, this, that, who, etc.) are words that we use to replace nouns (i.e., people, places, things), and there are many types of pronouns (e.g., personal, relative, demonstrative, etc.). However, expletive pronouns are different from other pronouns because unlike most pronouns, they do not stand for a person, thing, or place; they are called expletives because they have no “value.” Sometimes you will see expletive pronouns at the beginning of a sentence, sometimes at the end.

Examples: There are a lot of reading assignments in this class. I can’t believe how many reading assignments there are! Note: These two examples are not necessarily bad examples of using expletive pronouns. They are included to help you first understand what expletive pronouns are so you can recognize them. |

The main reason you should generally avoid writing with expletive pronouns is that they often cause us to use more words in the rest of the sentence than we have to. Also, the empty words at the beginning tend to shift the more important subject matter toward the end of the sentence. The above sentences are not that bad, but at least they are simple enough to help you understand what expletive pronouns are. Here are some more examples of expletive pronouns, along with better alternatives.

Examples Original: There are some people who love to cause trouble. Revision: Some people love to cause trouble. Original: There are some things that are just not worth waiting for. Revision: Some things are just not worth waiting for. Original: There is a person I know who can help you fix your computer. Revision: I know a person who can help you fix your computer. |

While not all instances of expletive pronouns are bad, writing sentences with expletives seems to be habit forming. It can lead to trouble when you are explaining more complex ideas, because you end up having to use additional strings of phrases to explain what you want your reader to understand. Wordy sentences, such as those with expletive pronouns, can tax the reader’s mind.

Example Original: There is a button you need to press that is red and says STOP. Revision: You need to press the red STOP button. Or: Press the red STOP button. |

When you find yourself using expletives, always ask yourself if omitting and rewriting would give your reader a clearer, more direct, less wordy sentence. Can I communicate the same message using fewer words without taking away from the meaning I want to convey or the tone I want to create?

You will give clearer information if you write with specific rather than general words. Evoke senses of taste, smell, hearing, sight, and touch with your word choices. For example, you could say, “My shoe feels odd.” But this statement does not give a sense of why your shoe feels odd, since “odd” is an abstract word that does not suggest any physical characteristics. Or you could say, “My shoe feels wet.” This statement gives you a sense of how your shoe feels to the touch. It also gives a sense of how your shoe might look as well as how it might smell, painting a picture for your readers. See the table below to compare general and specific words.

Bailey, E. P. (2008). Plain English at work: A guide to business writing and speaking. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

This chapter contains material taken from Part 1 “Foundations” in the Professional Communications OER by the Olds College OER Development Team (used under a CC-BY 4.0 International license) and Chapter 6.2 “Writing style” in Business Communication for Success (used under a CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0 International license). You can download Professional Communications OER for free at http://www.procomoer.org/

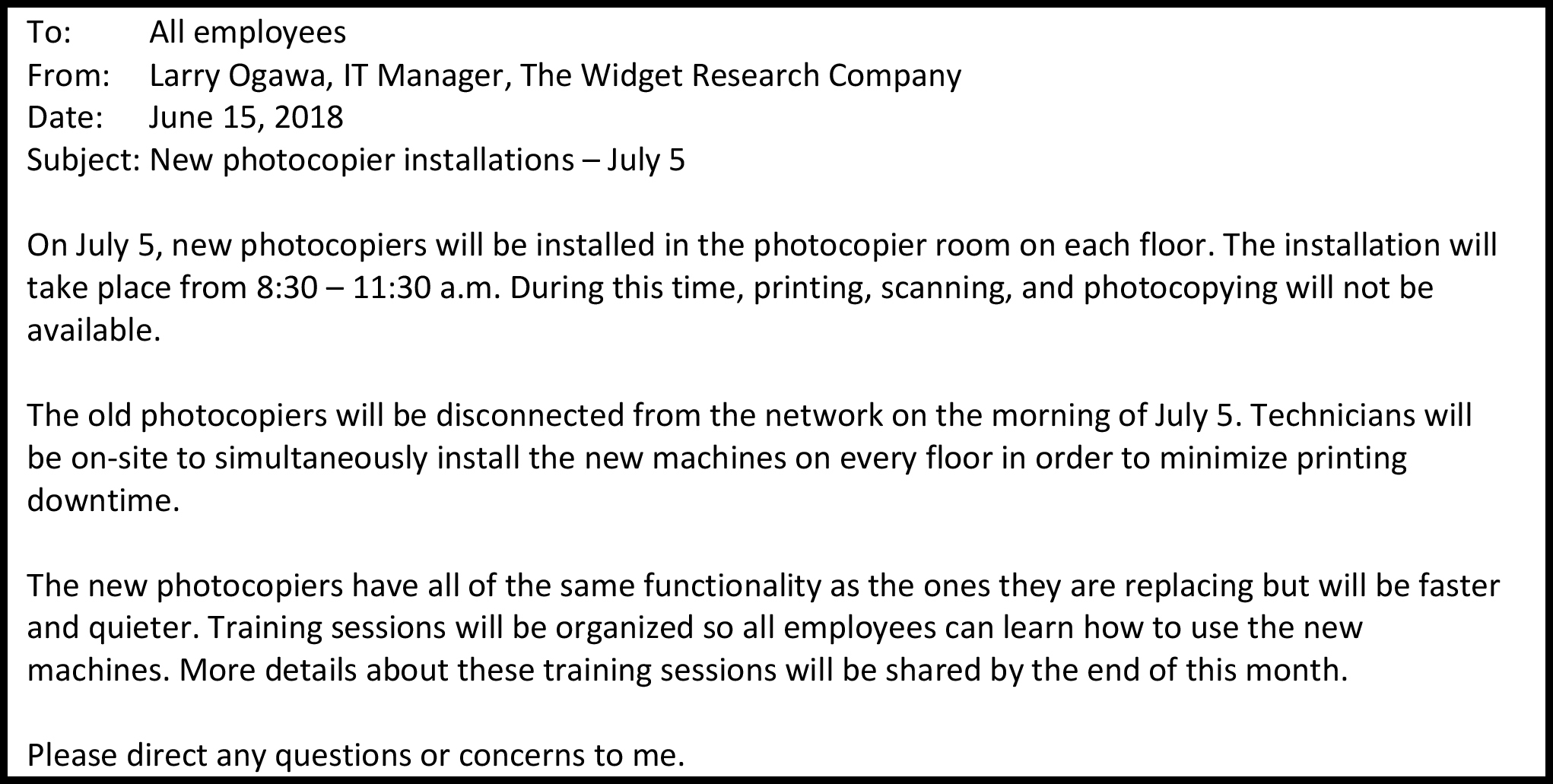

A memo (or memorandum, meaning “reminder”) is normally used for communicating policies, procedures, or related official business within an organization. It is often written from a one-to-all perspective (like mass communication), broadcasting a message to an audience, rather than a one-on-one, interpersonal communication. It may also be used to update a team on activities for a given project or to inform a specific group within a company of an event, action, or observance.

A memo’s purpose is often to inform and represent the business or organization’s interests, but it occasionally includes an element of persuasion or a call to action. All organizations have informal and formal communication networks. The unofficial, informal communication network within an organization is often called the grapevine, and it is often characterized by rumour, gossip, and innuendo. On the grapevine, one person may hear that someone else is going to be laid off and start passing the news around. Rumours change and transform as they are passed from person to person, and before you know it, the word is that they are shutting down your entire department.

One effective way to address informal, unofficial speculation is to spell out clearly for all employees what is going on with a particular issue. If budget cuts are a concern, then it may be wise to send a memo explaining the changes that are imminent. If a company wants employees to take action, they may also issue a memorandum.

A memo has a header with guide words that clearly indicate who sent the memo, who the intended recipients are, the date of the memo, and a descriptive subject line. The content of each guide word field aligns. The message then follows the header, and it typically includes a declaration (introduction), a discussion, and a summary.

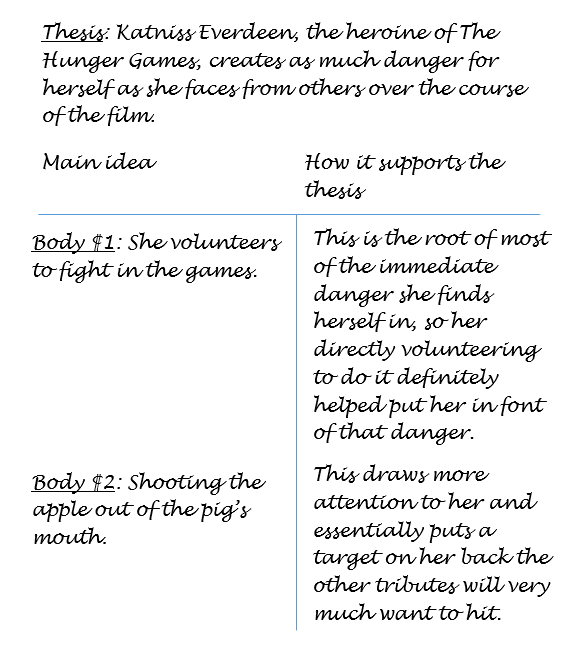

Figure 4.1.1 shows a sample memo.

Figure 4.1.1. A sample memo (Melissa Ashman, 2018, CC-BY-NC 4.0 international license)

Always consider the audience and their needs when preparing a memo (or any message for that matter). An acronym or abbreviation that is known to management may not be known by all the employees of the organization, and if the memo is to be posted and distributed within the organization, the goal is to be clear and concise communication at all levels with no ambiguity.

Memos are often announcements, and the person sending the memo speaks for a part or all of the organization. Use a professional tone at all times.

The topic of the memo is normally declared in the subject line, and it should be clear, concise, and descriptive. If the memo is announcing the observance of a holiday, for example, the specific holiday should be named in the subject line—for example, use “Thanksgiving weekend schedule” rather than “holiday observance.”

Some written business communication allows for a choice between direct and indirect formats, but memorandums are almost always direct. The purpose is clearly announced immediately and up-front, and the explanation or supporting information then follows.

Memos should have an objective tone without personal bias, preference, or interest on display. Avoid subjectivity.

This chapter contains material taken from Chapter 9.2 “Memorandums and letters” in Business Communication for Success and is used under a CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0 International license.

Letters are brief messages sent to recipients that are often outside the organization (Bovee & Thill, 2010). They are often printed on letterhead paper and represent the business or organization in one or two pages. Shorter messages may include e-mails or memos, either hard copy or electronic, while reports tend to be three or more pages in length.

While e-mail and text messages may be used more frequently today, the business letter remains a common form of written communication. It can serve to introduce you to a potential employer, announce a product or service, or even serve to communicate feelings and emotions. We’ll examine the basic outline of a letter and then focus on specific products or writing assignments.

All business messages have expectations in terms of language and format. The audience or reader also may have their own idea of what constitutes a specific type of letter, and your organization may have its own format and requirements. There are many types of letters, and many adaptations in terms of form and content. In this chapter, we discuss the fifteen elements of a traditional block-style letter.

Letters may serve to introduce your skills and qualifications to prospective employers, deliver important or specific information, or serve as documentation of an event or decision. Regardless of the type of letter you need to write, it can contain up to fifteen elements in five areas. While you may not use all the elements in every case or context, they are listed in Table 4.2.1.

Table 4.2.1 Elements of a business letter

| Content | Guidelines |

|---|---|

| 1. Return address | This is your address where someone could send a reply. If your letter includes a letterhead with this information, either in the header (across the top of the page) or the footer (along the bottom of the page), you do not need to include it before the date. |

| 2. Date | The date should be placed at the top, right or left justified, five lines from the top of the page or letterhead logo. |

| 3. Reference (Re:) *optional | Like a subject line in an e-mail, this is where you indicate what the letter is in reference to, the subject or purpose of the document. |

| 4. Delivery *optional | Sometimes you want to indicate on the letter itself how it was delivered. This can make it clear to a third party that the letter was delivered via a specific method, such as certified mail (a legal requirement for some types of documents). |

| 5. Recipient note *optional | This is where you can indicate if the letter is personal or confidential. |