Literature Reviews for Education and Nursing Graduate Students by Linda Frederiksen is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Literature Reviews for Education and Nursing Graduate Students by Linda Frederiksen is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Congratulations! You applied and were accepted into a graduate-level program at [fill in the blank] university. In your first research methods class, your assignment is to do a comprehensive literature review on a topic of your choice. It sounds easy enough – just find a few articles related to your topic and summarize, right? You probably did this type of annotated bibliography as an undergraduate and are pretty optimistic about doing another one. As the professor and other classmates talk more about the demands and expectations for this literature review, however, you may begin to feel less confident. If it’s any consolation, you are not alone.

Writing a literature review involves a synthesis of a complex range of analytical and rhetorical skills as well as academic writing skills, and an understanding of what is meant by critical analysis and argument.(Turner & Bitchener, 2008).

At the same time, there is often a disconnect between what faculty expect in terms of research and writing skills and what incoming graduate students understand about how to conduct a literature review. At the graduate level, and especially when preparing a thesis or dissertation, the literature review is a high-stakes document that introduces the novice researcher to the scholarly conversation of his/her discipline for the first time. Students are often surprised that the specific research and writing skills needed to do a graduate-level literature review aren’t taught in class, while faculty may assume students already have these skills (Harris, 2011). As a result, “most graduate students receive little or no formal training in how to analyze and synthesize the research literature in their field” (Boote & Beile, 2005, p. 5). It is for these students that we write this book.

Literature Reviews for Education and Nursing Graduate Students introduces you to the components of the stand-alone literature review and prepares you to write one of your own. This open textbook is designed to help students in graduate-level nursing and education programs recognize the significant role the literature review plays in the research process and synthesize and cite key sources with confidence. Although specific examples are generally nursing or education related, most of the content is also applicable to other students in the social sciences. Likewise, this textbook is openly licensed, meaning it is available at no cost to anyone in the world who would like to use it. Instructors (and others) may freely edit or modify it and assign as much or as little as needed.

Literature Reviews for Education and Nursing Graduate Students is written for new graduate students and novice researchers just entering the work of their chosen discipline. It is meant to assist “students who can complete course assignments to scholars who can make a contribution to their respective fields.” (Switzer & Perdue, 2011, p. 12). The book was written by two librarians with expertise guiding nursing and education graduate students through the literature review research and writing process. We include in the book examples from the literature of nursing and education to facilitate a greater understanding of what it means to be a successful graduate student. Our intent is to promote the idea that the literature review is a dynamic and complex synthesis of research and writing that is quite different than an annotated bibliography.

Literature Reviews for Education and Nursing Graduate Students covers topics related to literature review research and writing. Chapter 1 provides an overview of literature reviews and their purpose. Chapters 2 and 3 relate to getting started with the review, including how to develop a research question or hypothesis. Chapters 4 and 5 deal with the research process, that is, where to find relevant sources and how to evaluate their credibility. Chapters 6 and 7 discuss how to document sources and, one of the most difficult tasks novice researchers face, how to synthesize information. Chapter 8 is focused on writing your own literature review. A short conclusion and an answer key to questions asked in previous chapters complete the text. Each chapter begins with a summary of learning objectives for that chapter and concludes with a set of questions to assess your understanding of the topics covered. Examples, tutorials, videos, additional resources, websites and/or activities are provided. Finally, at the end of each chapter you will find a list of works cited as well as image attributions.

Although this textbook does not contain all of the answers you will need to successfully write a literature review, the authors hope that when used in combination with all of the other experiences you will have as a graduate student, it will help you to become the researcher and scholar you want to be.

Boote, D.N., & Beile, P. (2005). Scholars before researchers: On the centrality of the dissertation literature review in research preparation. Educational Researcher 34(6), 3-15.

Harris, C.S. (2011). The case for partnering doctoral students with librarians: A synthesis of the literatures. Library Review 60(7), 599-620.

Switzer, A., & Perdue, A.S. (2011). Dissertation 101: A research and writing intervention for education graduate students. Education Libraries 34(1), 4-14.

Turner, E., & Bitchener, J. (2008). An approach to teaching the writing of literature reviews. Zeitschrift Schreiben. https://zeitschrift-schreiben.eu/globalassets/zeitschrift-schreiben.eu/2008/turner_approach_teaching.pdf

If you adopt this book, as a core or supplemental resource, please report your adoption in order for us to celebrate your support of students’ savings. Report your commitment at www.openlibrary.ecampusontario.ca.

We invite you to adapt this book further to meet your and your students’ needs. Please let us know if you do! If you would like to use Pressbooks, the platform used to make this book, contact eCampusOntario for an account using open@ecampusontario.ca.

If this text does not meet your needs, please check out our full library at www.openlibrary.ecampusontario.ca. If you still cannot find what you are looking for, connect with colleagues and eCampusOntario to explore creating your own open education resource (OER).

eCampusOntario is a not-for-profit corporation funded by the Government of Ontario. It serves as a centre of excellence in online and technology-enabled learning for all publicly funded colleges and universities in Ontario and has embarked on a bold mission to widen access to post-secondary education and training in Ontario. This textbook is part of eCampusOntario’s open textbook library, which provides free learning resources in a wide range of subject areas. These open textbooks can be assigned by instructors for their classes and can be downloaded by learners to electronic devices or printed for a low cost by our printing partner, The University of Waterloo. These free and open educational resources are customizable to meet a wide range of learning needs, and we invite instructors to review and adopt the resources for use in their courses.

At the conclusion of this chapter, you will be able to:

Pick up nearly any book on research methods and you will find a description of a literature review. At a basic level, the term implies a survey of factual or nonfiction books, articles, and other documents published on a particular subject. Definitions may be similar across the disciplines, with new types and definitions continuing to emerge. Generally speaking, a literature review is a:

As a foundation for knowledge advancement in every discipline, it is an important element of any research project. At the graduate or doctoral level, the literature review is an essential feature of thesis and dissertation, as well as grant proposal writing. That is to say, “A substantive, thorough, sophisticated literature review is a precondition for doing substantive, thorough, sophisticated research…A researcher cannot perform significant research without first understanding the literature in the field.” (Boote & Beile, 2005, p. 3). It is by this means, that a researcher demonstrates familiarity with a body of knowledge and thereby establishes credibility with a reader. An advanced-level literature review shows how prior research is linked to a new project, summarizing and synthesizing what is known while identifying gaps in the knowledge base, facilitating theory development, closing areas where enough research already exists, and uncovering areas where more research is needed. (Webster & Watson, 2002, p. xiii)

A graduate-level literature review is a compilation of the most significant previously published research on your topic. Unlike an annotated bibliography or a research paper you may have written as an undergraduate, your literature review will outline, evaluate and synthesize relevant research and relate those sources to your own thesis or research question. It is much more than a summary of all the related literature.

It is a type of writing that demonstrate the importance of your research by defining the main ideas and the relationship between them. A good literature review lays the foundation for the importance of your stated problem and research question.

Literature reviews:

The purpose of a literature review is to demonstrate that your research question is meaningful. Additionally, you may review the literature of different disciplines to find deeper meaning and understanding of your topic. It is especially important to consider other disciplines when you do not find much on your topic in one discipline. You will need to search the cognate literature before claiming there is “little previous research” on your topic.

Well developed literature reviews involve numerous steps and activities. The literature review is an iterative process because you will do at least two of them: a preliminary search to learn what has been published in your area and whether there is sufficient support in the literature for moving ahead with your subject. After this first exploration, you will conduct a deeper dive into the literature to learn everything you can about the topic and its related issues.

This video is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 by NCSU Libraries. Transcript.

An effective literature review must:

All literature reviews, whether they are qualitative, quantitative or both, will at some point:

There are many different types of literature reviews, however there are some shared characteristics or features. Remember a comprehensive literature review is, at its most fundamental level, an original work based on an extensive critical examination and synthesis of the relevant literature on a topic. As a study of the research on a particular topic, it is arranged by key themes or findings, which may lead up to or link to the research question. In some cases, the research question will drive the type of literature review that is undertaken.

The following section includes brief descriptions of the terms used to describe different literature review types with examples of each. The included citations are open access, Creative Commons licensed or copyright-restricted.

Guided by an understanding of basic issues rather than a research methodology. You are looking for key factors, concepts or variables and the presumed relationship between them. The goal of the conceptual literature review is to categorize and describe concepts relevant to your study or topic and outline a relationship between them. You will include relevant theory and empirical research.

Examples of a Conceptual Review:

An empirical literature review collects, creates, arranges, and analyzes numeric data reflecting the frequency of themes, topics, authors and/or methods found in existing literature. Empirical literature reviews present their summaries in quantifiable terms using descriptive and inferential statistics.

Examples of an Empirical Review:

Unlike a synoptic literature review, the purpose here is to provide a broad approach to the topic area. The aim is breadth rather than depth and to get a general feel for the size of the topic area. A graduate student might do an exploratory review of the literature before beginning a synoptic, or more comprehensive one.

Examples of an Exploratory Review:

A type of literature review limited to a single aspect of previous research, such as methodology. A focused literature review generally will describe the implications of choosing a particular element of past research, such as methodology in terms of data collection, analysis and interpretation.

Examples of a Focused Review:

Critiques past research and draws overall conclusions from the body of literature at a specified point in time. Reviews, critiques, and synthesizes representative literature on a topic in an integrated way. Most integrative reviews are intended to address mature topics or emerging topics. May require the author to adopt a guiding theory, a set of competing models, or a point of view about a topic. For more description of integrative reviews, see Whittemore & Knafl (2005).

Examples of an Integrative Review:

A subset of a systematic review, that takes findings from several studies on the same subject and analyzes them using standardized statistical procedures to pool together data. Integrates findings from a large body of quantitative findings to enhance understanding, draw conclusions, and detect patterns and relationships. Gather data from many different, independent studies that look at the same research question and assess similar outcome measures. Data is combined and re-analyzed, providing a greater statistical power than any single study alone. It’s important to note that not every systematic review includes a meta-analysis but a meta-analysis can’t exist without a systematic review of the literature.

Examples of a Meta-Analysis:

An overview of research on a particular topic that critiques and summarizes a body of literature. Typically broad in focus. Relevant past research is selected and synthesized into a coherent discussion. Methodologies, findings and limits of the existing body of knowledge are discussed in narrative form. Sometimes also referred to as a traditional literature review. Requires a sufficiently focused research question. The process may be subject to bias that supports the researcher’s own work.

Examples of a Narrative/Traditional Review:

Aspecific type of literature review that is theory-driven and interpretative and is intended to explain the outcomes of a complex intervention program(s).

Examples of a Realist Review:

Tend to be non-systematic and focus on breadth of coverage conducted on a topic rather than depth. Utilize a wide range of materials; may not evaluate the quality of the studies as much as count the number. One means of understanding existing literature. Aims to identify nature and extent of research; preliminary assessment of size and scope of available research on topic. May include research in progress.

Examples of a Scoping Review:

Unlike an exploratory review, the purpose is to provide a concise but accurate overview of all material that appears to be relevant to a chosen topic. Both content and methodological material is included. The review should aim to be both descriptive and evaluative. Summarizes previous studies while also showing how the body of literature could be extended and improved in terms of content and method by identifying gaps.

Examples of a Synoptic Review:

A rigorous review that follows a strict methodology designed with a presupposed selection of literature reviewed. Undertaken to clarify the state of existing research, the evidence, and possible implications that can be drawn from that. Using comprehensive and exhaustive searching of the published and unpublished literature, searching various databases, reports, and grey literature. Transparent and reproducible in reporting details of time frame, search and methods to minimize bias. Must include a team of at least 2-3 and includes the critical appraisal of the literature. For more description of systematic reviews, including links to protocols, checklists, workflow processes, and structure see “A Young Researcher’s Guide to a Systematic Review“.

Examples of a Systematic Review:

Compiles evidence from multiple systematic reviews into one document. Focuses on broad condition or problem for which there are competing interventions and highlights reviews that address those interventions and their effects. Often used in recommendations for practice.

Examples of an Umbrella/Overview Review:

For a brief discussion see “Not all literature reviews are the same” (Thomson, 2013).

The purpose of the literature review is the same regardless of the topic or research method. It tests your own research question against what is already known about the subject.

The outcome of your review is expected to demonstrate that you:

Graduate-level literature reviews are more than a summary of the publications you find on a topic. As you have seen in this brief introduction, literature reviews are a very specific type of research, analysis, and writing. We will explore these topics more in the next chapters. Some things to keep in mind as you begin your own research and writing are ways to avoid the most common errors seen in the first attempt at a literature review. For a quick review of some of the pitfalls and challenges a new researcher faces when he/she begins work, see “Get Ready: Academic Writing, General Pitfalls and (oh yes) Getting Started!”.

As you begin your own graduate-level literature review, try to avoid these common mistakes:

In conclusion, the purpose of a literature review is three-fold:

A literature review is commonly done today using computerized keyword searches in online databases, often working with a trained librarian or information expert. Keywords can be combined using the Boolean operators, “and”, “or” and sometimes “not” to narrow down or expand the search results. Once a list of articles is generated from the keyword and subject heading search, the researcher must then manually browse through each title and abstract, to determine the suitability of that article before a full-text article is obtained for the research question.

Literature reviews should be reasonably complete, and not restricted to a few journals, a few years, or a specific methodology or research design. Reviewed articles may be summarized in the form of tables, and can be further structured using organizing frameworks such as a concept matrix.

A well-conducted literature review should indicate whether the initial research questions have already been addressed in the literature, whether there are newer or more interesting research questions available, and whether the original research questions should be modified or changed in light of findings of the literature review.

The review can also provide some intuitions or potential answers to the questions of interest and/or help identify theories that have previously been used to address similar questions and may provide evidence to inform policy or decision-making. (Bhattacherjee, 2012).

Read Abstract 1. Refer to Types of Literature Reviews. What type of literature review do you think this study is and why? See the Answer Key for the correct response.

Nursing: To describe evidence of international literature on the safe care of the hospitalised child after the World Alliance for Patient Safety and list contributions of the general theoretical framework of patient safety for paediatric nursing.

An integrative literature review between 2004 and 2015 using the databases PubMed, Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Scopus, Web of Science and Wiley Online Library, and the descriptors Safety or Patient safety, Hospitalised child, Paediatric nursing, and Nursing care.

Thirty-two articles were analysed, most of which were from North American, with a descriptive approach. The quality of the recorded information in the medical records, the use of checklists, and the training of health workers contribute to safe care in paediatric nursing and improve the medication process and partnerships with parents.

General information available on patient safety should be incorporated in paediatric nursing care. (Wegner, Silva, Peres, Bandeira, Frantz, Botene, & Predebon, 2017).

Read Abstract 2. Refer to Types of Literature Reviews. What type of lit review do you think this study is and why? See the Answer Key for the correct response.

Education: The focus of this paper centers around timing associated with early childhood education programs and interventions using meta-analytic methods. At any given assessment age, a child’s current age equals starting age, plus duration of program, plus years since program ended. Variability in assessment ages across the studies should enable everyone to identify the separate effects of all three time-related components. The project is a meta-analysis of evaluation studies of early childhood education programs conducted in the United States and its territories between 1960 and 2007. The population of interest is children enrolled in early childhood education programs between the ages of 0 and 5 and their control-group counterparts. Since the data come from a meta-analysis, the population for this study is drawn from many different studies with diverse samples. Given the preliminary nature of their analysis, the authors cannot offer conclusions at this point. (Duncan, Leak, Li, Magnuson, Schindler, & Yoshikawa, 2011).

See Answer Key for the correct responses.

The purpose of a graduate-level literature review is to summarize in as many words as possible everything that is known about my topic.

A literature review is significant because in the process of doing one, the researcher learns to read and critically assess the literature of a discipline and then uses it appropriately to advance his/her own research.

Read the following abstract and choose the correct type of literature review it represents.

Nursing: E-cigarette use has become increasingly popular, especially among the young. Its long-term influence upon health is unknown. Aim of this review has been to present the current state of knowledge about the impact of e-cigarette use on health, with an emphasis on Central and Eastern Europe. During the preparation of this narrative review, the literature on e-cigarettes available within the network PubMed was retrieved and examined. In the final review, 64 research papers were included. We specifically assessed the construction and operation of the e-cigarette as well as the chemical composition of the e-liquid; the impact that vapor arising from the use of e-cigarette explored in experimental models in vitro; and short-term effects of use of e-cigarettes on users’ health. Among the substances inhaled by the e-smoker, there are several harmful products, such as: formaldehyde, acetaldehyde, acroleine, propanal, nicotine, acetone, o-methyl-benzaldehyde, carcinogenic nitrosamines. Results from experimental animal studies indicate the negative impact of e-cigarette exposure on test models, such as ascytotoxicity, oxidative stress, inflammation, airway hyper reactivity, airway remodeling, mucin production, apoptosis, and emphysematous changes. The short-term impact of e-cigarettes on human health has been studied mostly in experimental setting. Available evidence shows that the use of e-cigarettes may result in acute lung function responses (e.g., increase in impedance, peripheral airway flow resistance) and induce oxidative stress. Based on the current available evidence, e-cigarette use is associated with harmful biologic responses, although it may be less harmful than traditional cigarettes. (Jankowski, Brożek, Lawson, Skoczyński, & Zejda, 2017).

Read the following abstract and choose the correct type of literature review it represents.

Education: In this review, Mary Vorsino writes that she is interested in keeping the potential influences of women pragmatists of Dewey’s day in mind while presenting modern feminist re readings of Dewey. She wishes to construct a narrowly-focused and succinct literature review of thinkers who have donned a feminist lens to analyze Dewey’s approaches to education, learning, and democracy and to employ Dewey’s works in theorizing on gender and education and on gender in society. This article first explores Dewey as both an ally and a problematic figure in feminist literature and then investigates the broader sphere of feminist pragmatism and two central themes within it: (1) valuing diversity, and diverse experiences; and (2) problematizing fixed truths. (Vorsino, 2015).

At the conclusion of this chapter, you will be able to:

Because a literature review is a summary and analysis of the relevant publications on a topic, we first have to understand what is meant by ‘the literature’. In this case, ‘the literature’ is a collection of all of the relevant written sources on a topic. It will include both theoretical and empirical works. Both types provide scope and depth to a literature review.

Figure 2.1

When drawing boundaries around an idea, topic, or subject area, it helps to think about how and where the information for the field is produced. For this, you need to identify the disciplines of knowledge production in a subject area.

Information does not exist in the environment like some kind of raw material. It is produced by individuals working within a particular field of knowledge who use specific methods for generating new information. Disciplines are knowledge-producing and -disseminating systems which consume, produce and disseminate knowledge. Looking through a course catalog of a post-secondary educational institution gives clues to the structure of a discipline structure. Fields such as political science, biology, history and mathematics are unique disciplines, as are education and nursing, with their own logic for how and where new knowledge is introduced and made accessible.

You will need to become comfortable with identifying the disciplines that might contribute information to any search strategy. When you do this, you will also learn how to decode the way how people talk about a topic within a discipline. This will be useful to you when you begin a review of the literature in your area of study.

For example, think about the disciplines that might contribute information to a the topic such as the role of sports in society. Try to anticipate the type of perspective each discipline might have on the topic. Consider the following types of questions as you examine what different disciplines might contribute:

In this example, we identify two disciplines that have something to say about the role of sports in society: allied health and education. What would each of these disciplines raise as key questions or issues related to that topic?

We see that a single topic can be approached from many different perspectives depending on how the disciplinary boundaries are drawn and how the topic is framed. This step of the research process requires you to make some decisions early on to focus the topic on a manageable and appropriate scope for the rest of the strategy. (Hansen & Paul, 2015).

‘The literature’ consists of the published works that document a scholarly conversation in a field of study. You will find, in ‘the literature,’ documents that explain the background of your topic so the reader knows where you found loose ends in the established research of the field and what led you to your own project. Although your own literature review will focus on primary, peer-reviewed resources, it will begin by first grounding yourself in background subject information generally found in secondary and tertiary sources such as books and encyclopedias. Once you have that essential overview, you delve into the seminal literature of the field. As a result, while your literature review may consist of research articles tightly focused on your topic with secondary and tertiary sources used more sparingly, all three types of information (primary, secondary, tertiary) are critical to your research.

‘The literature’ is published in books, journal articles, conference proceedings, theses and dissertations. It can also be found in newspapers, encyclopedias, textbooks, as well as websites and reports written by government agencies and professional organizations. While these formats may contain what we define as ‘the literature’, not all of it will be appropriate for inclusion in your own literature review.

These sources are found through different tools that we will discuss later in this section. Although a discovery tool, such as a database or catalog, may link you to the ‘the literature’ not every tool is appropriate to every literature review. No single source will have all of the information resources you should consult. A comprehensive literature review should include searches in the following:

To get a better idea of how the literature in a discipline develops, it’s useful to see how the information publication lifecycle works. These distinct stages show how information is created, reviewed, and distributed over time.

Follow the image link to view the full tutorial.

Follow the image link to view the full tutorial.

The following chart can be used to guide you in searching literature existing at various stages of the scholarly communication process (freely accessible sources are linked, subscription or subscribed sources are listed but not linked):

| Steps in the Scholarly Communication Process | Publication Cycle | Access Points |

| Research and develop idea | Unpublished documents such as lab notebooks, personal correspondence, graphs, charts, grant proposals, and other ‘grey literature’ | Limited access HSRR (Health Services and Sciences Research Resources) RePORTER (Database of NIH funded research projects) |

| Present preliminary findings | Preliminary reports: letters to the editor or journals, brief (short) communication submitted to a primary journal | PubMed (limiting search results to Letter under Limits) Web of Science (Science Citation Index) |

| Report research | Conference literature: preprints, conference proceedings | PapersFirst ProceedingsFirst Conference web sites |

| Research reports: master’s theses, doctoral dissertations, interim or technical reports | Dissertations & Theses Electronic Theses and Dissertations Center PubMed (limiting search results to Technical Report under Limits) Current Grey Literature Report Professional association web sites | |

| Publish research | Research paper (scholarly journal articles): research papers published in peer-reviewed/refereed journals | PubMed CINAHL PsycINFO Web of Science |

| Popularize research findings | Newspapers, popular magazines, TV news reports, trade publications, web sites | PubMed (limiting search results to News and Newspaper Article under Limits) Media outlets Internet search engines |

| Compact and repackage information | Reviews, systematic reviews, guidelines, textbooks, handbooks, yearbooks, encyclopedias | Cochrane Library Library Catalogs |

To continue our discussion of information sources, there are two ways published information in the field can be categorized:

Journals, trade publications, and magazines are all periodicals, and articles from these publications they can all look similar article by article when you are searching in the databases. It is good to review the differences and think about when to use information from each type of periodical.

A magazine is a collection of articles and images about diverse topics of popular interest and current events.

Features of magazines:

Popular magazines like Psychology Today, Sports Illustrated, and Rolling Stone can be good sources for articles on recent events or pop-culture topics, while Harpers, Scientific American, and The New Republic will offer more in-depth articles on a wider range of subjects. These articles are geared towards readers who, although not experts, are knowledgeable about the issues presented.

Trade publications or trade journals are periodicals directed to members of a specific profession. They often have information about industry trends and practical information for people working in the field.

Features of trade publications:

|  |

Trade publications are geared towards professionals in a discipline. They report news and trends in a field, but not original research. They may provide product or service reviews, job listings, and advertisements.

Scholarly, academic, and scientific publications are a collections of articles written by scholars in an academic or professional field. Most journals are peer-reviewed or refereed, which means a panel of scholars reviews articles to decide if they should be accepted into a specific publication. Journal articles are the main source of information for researchers and for literature reviews.

Features of journals:

|  |

Scholarly journals provider articles of interest to experts or researchers in a discipline. An editorial board of respected scholars (peers) reviews all articles submitted to a journal. They decide if the article provides a noteworthy contribution to the field and should be published. There are typically few little or no advertisements. Articles published in scholarly journals will include a list of references.

Increasingly, scholars are publishing findings and original research in open access journals. Open access journals are scholarly and peer-reviewed and open access publishers provide unrestricted access and unrestricted use. Open access is a means of disseminating scholarly research that breaks from the traditional subscription model of academic publishing. It is free of charge to readers and because it is online, it is available at anytime, anywhere in the world, to anyone with access to the internet. The Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ) indexes and provides access to high-quality, peer-reviewed scholarly articles.

In summary, newspapers and other popular press publications are useful for getting general topic ideas. Trade publications are useful for practical application in a profession and may also be a good source of keywords for future searching. Scholarly journals are the conversation of the scholars who are doing research in a specific discipline and publishing their research findings.

Primary sources of information are those types of information that come first. Some examples of primary sources are:

There are different types of primary sources for different disciplines. In the discipline of history, for example, a diary or transcript of a speech is a primary source. In education and nursing, primary sources will generally be original research, including data sets.

Secondary sources are written about primary sources to interpret or analyze them. They are a step or more removed from the primary event or item. Some examples of secondary sources are:

Tertiary sources are further removed from the original material and are a distillation and collection of primary and secondary sources. Some examples are:

A comparison of information sources across disciplines:

| SUBJECT | PRIMARY | SECONDARY | TERTIARY |

| Education | Journal article reporting on quantitative study of after school programs | Article in Teacher Magazine about after school programs | Handbook of afterschool programming ERIC database |

| Nursing | Journal article reporting on a Cclinical trial of a treatment or device | Systematic review of treatment or device, such as those found in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews | Encyclopedia of Nursing Research |

| Psychology | Patient notes taken by clinical psychologist | Magazine article about the patient’s psychological condition | Textbook on clinical psychology |

In this section, we discuss how to find not only information, but the sources of information in your discipline or topic area. As we see in the graphic and chart above, the information you need for your literature review will be located in multiple places. How and where research and publication occurs drives how and where the information is located, which in turn determines how you will discover and retrieve it. When we talk about information sources for a literature review in education or nursing, we generally mean these five areas: the internet, reference material and other books, empirical or evidence-based articles in scholarly, peer-reviewed journals, conference proceedings and papers, dissertations and theses, and grey literature.

The World Wide Web can be an excellent place to satisfy some initial research needs.

Reference materials and books are available in both print and electronic formats. They provide gateway knowledge to a subject area and are useful at the beginning of the research process to:

Another major category of information sources is scholarly information produced by subject experts working in academic institutions, research centers and scholarly organizations. Scholars and researchers generate information that advances our knowledge and understanding of the world. The research they do creates new opportunities for inventions, practical applications, and new approaches to solving problems or understanding issues.

Academics, researchers and students at universities make their contributions to scholarly knowledge available in many forms:

Scholars and researchers introduce their discoveries to the world in a formal system of information dissemination that has developed over centuries. Because scholarly research undergoes a process of “peer review” before being published (meaning that other experts review the work and pass judgment about whether it is worthy of publication), the information you find from scholarly sources meets preset standards for accuracy, credibility and validity in that field.

Likewise, scholarly journal articles are generally considered to be among the most reliable sources of information because they have gone through a peer-review process.

Conferences are a major source of emerging research where researchers present papers on their current research and obtain feedback from the audience. The papers presented in the conference are then usually published in a volume called a conference proceeding. Conference proceedings highlight current discussion in a discipline and can lead you to scholars who are interested in specific research areas.

A word about conference papers: several factors contribute to making these documents difficult to find. It may be months before a paper is published as a journal article, or it may never be published. Publishers and professional associations are inconsistent in how they publish proceedings. For example, the papers from an annual conference may be published as individual, stand-alone titles, which may be indexed in a library catalog, or the conference proceedings may be treated more like a periodical or serial and, therefore, indexed in a journal database.

It is not unusual that papers delivered at professional conferences are not published in print or electronic form, although an abstract may be available. In these cases, the full paper may only be available from the author or authors.

The most important thing to remember is that if you have any difficulty finding a conference proceeding or paper, ask a librarian for assistance.

Dissertations and theses can be rich sources of information and have extensive reference lists to scan for resources. They are considered gray literature, so are not “peer reviewed”. The accuracy and validity of the paper itself may depend on the school that awarded the doctoral or master’s degree to the author.

In thinking about ‘the literature’ of your discipline, you are beginning the first step in writing your own literature review. By understanding what the literature in your field is, as well as how and when it is generated, you begin to know what is available and where to look for it.

We briefly discussed seven types of (sometimes overlapping) information:

By conceptualizing or scoping how and where the literature of your discipline or topic area is generated, you have started on your way to writing your own literature review.

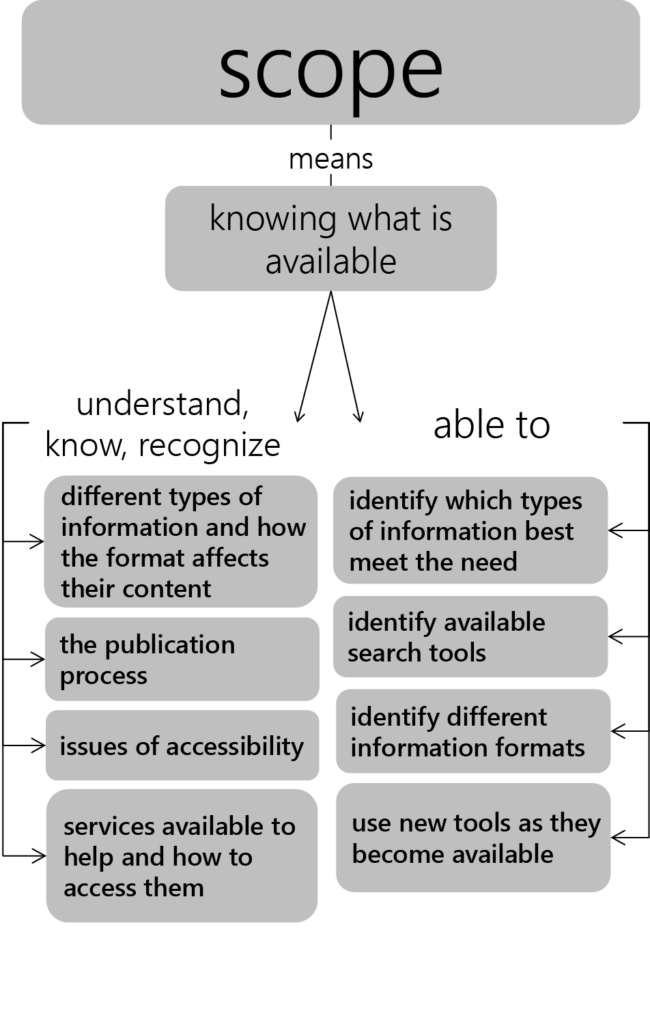

Figure 2.3 Information literacy skills

Finally, remember:

“All information sources are not created equal. Sources can vary greatly in terms of how carefully they are researched, written, edited, and reviewed for accuracy. Common sense will help you identify obviously questionable sources, such as tabloids that feature tales of alien abductions, or personal websites with glaring typos. Sometimes, however, a source’s reliability—or lack of it—is not so obvious…You will consider criteria such as the type of source, its intended purpose and audience, the author’s (or authors’) qualifications, the publication’s reputation, any indications of bias or hidden agendas, how current the source is, and the overall quality of the writing, thinking, and design.” (Writing for Success, 2015, p. 448).

We will cover how to evaluate sources in more detail in Chapter 5.

For each of these information needs, indicate what resources would be the best fit to answer your question. There may be more than one source so don’t feel like you have to limit yourself to only one. See Answer Key for the correct response.

Trade publication

Scholarly journal

Magazine

At the conclusion of this chapter, you will be able to:

If the longest journey begins with the first step, most graduate-level literature reviews begin with choosing a relevant, appropriate, interesting topic about which to do the review. Whether the topic is assigned, chosen from a list of possible options, or (most likely) developed on your own, a good way to begin your thinking is to take a general issue or subject and formulate it into a question. You may want to start to think about a single aspect in your field or discipline that might be interesting to pursue, such as ‘science education’ or ‘diabetes treatment.’

A good topic selection plan begins with a general orientation into the subject you are interested in pursuing in more depth. Although finding a good research question may initially feel like looking for a needle in a haystack, choosing a general topic is the first step.

Things to think about when choosing a topic area:

Other suggestions for choosing a topic include:

Although it’s a good idea to avoid subjects that are too personal or emotional as these can interfere with an unbiased approach to the research, it’s also important to make sure you have more than a passing interest in the topic. You will be with this literature review for an extended period of time and it will be difficult to stick with it even under the best circumstances. A graduate student in psychology said, “‘My advice would be to NOT choose a topic that is an unappealing offshoot of your adviser’s work or a project that you have lukewarm feelings about in general…It’s important to remember that this is a marathon, not a sprint, and lukewarm feelings can turn cold quickly.’” (Dittman, 2005).

Now, take that general idea and begin to think about it in terms of a question. What do you really want to know about the topic? As a warm-up exercise, try dropping a possible topic idea into one of the blank spaces below. The questions may help bring your subject into sharper focus and provide you with the first important steps towards developing your topic. The type of paper you want to write (Definition, Analysis, Narration, etc.) can also be a useful way to begin thinking about your research question. For example, if you’re interested in parent involvement in early childhood education, your research question might be “What are the various features of parent involvement in early childhood education?” Or, if you want to do an evaluative literature review, your research question could be “What is the value of infant vaccination?”

For more information about how to form a research question, check out this video tutorial:

At this point, you will want to do an initial review of the existing literature to see what resources on your topic or question already exist. Based on what you find, you may decide to alter your question in some way before going too far along a path that perhaps has already been well-covered by other scholars.

Some things to keep in mind at this beginning stage of the research process is whether your literature review will be in the form of a research question or a hypothesis. One way to determine that outcome is to compare the two and decide which format will work best for you. For example, if the area you are researching is a relatively new field, and there is little or no existing literature or theory that indicates what you will find, then your literature review will likely be based on a research question.

The question should express a relationship between two or more variables – for example, how is A related to B? It should be clearly stated in a question form – such as, “How do grades (A) affect participation in class (B)?” or “How does parental education level (A) affect children’s vaccination status (B)?” Your literature review, in turn, may become:

Grades as a classroom participation motivator: A literature review, or

Education level and vaccinations: A literature review

Your question should also imply possibilities for empirical testing–remember, metaphysical questions are not measurable and a variable that cannot be clearly defined cannot be tested.

If, however, your literature review tests something based on the findings of a large amount of previous literature or a well-developed theory, your literature review will be to test of a hypothesis, rather than answer a question. The statement should indicate an expected relationship between variables and it must be testable. State your hypothesis as simply and concisely as possible. For example, if A, then B, as in: “If patient is obese, he/she will also be deaf.” (Dhanda & Taheri, 2017). Or, “For those who stutter, unusual temperament or anxiety is a causal factor.” (Kefalianos, 2012)

| Research Question | Hypothesis |

| Is A related to B? | If A, then B |

| How are A and B related to C? | If A & B, then C |

| How is A related to B under conditions C and D? | If A, then B under conditions C and D |

Decide what type of relationship you would like to study between the variables. Now, try to express the relationship between the concepts as a single sentence–in the form of either a research question or a hypothesis.

Once you have selected your topic area and reviewed literature related to it, you may need to narrow it to something that can be realistically researched and answered. In addition to asking Who, What, When, Where, Why, and How questions, other types of questions you might begin to ask to further refine your topic include those that are: Descriptive, Differential or Comparative, Associative or Relational.

You might beginning by asking a series of PICO questions. Although the PICO method is used primarily in the health sciences, it can also be useful for narrowing/refining a research question in the social sciences as well. A way to formulate an answerable question using the PICO model could look something like this:

Some examples of how the PICO method is used to refine a research question include:

Another mnemonic technique used in the social sciences for narrowing a topic is SPICE. An example of how SPICE factors can be used to develop a research question is given below:

Setting – for example, Canada

Perspective – for example, Adolescents

Intervention – for example, Text message reminders

Comparisons – for example, Telephone message reminders

Evaluation – for example, Number of homework assignments turned in after text message reminder compared to the number of assignments turned in after a telephone reminder

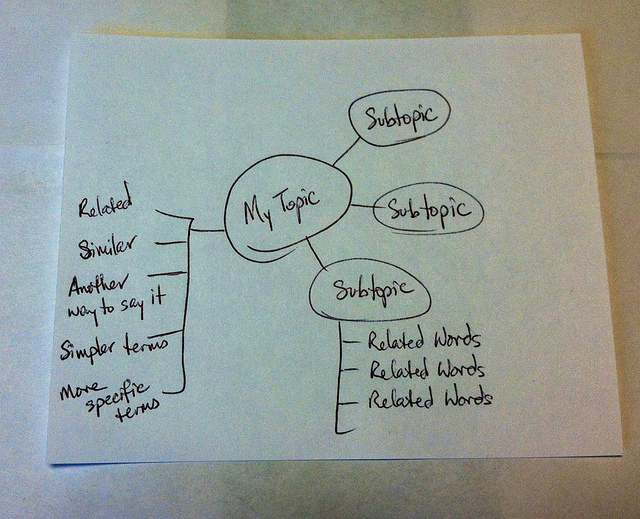

Likewise, developing a concept map or mind map around your topic may help you analyze your question and determine more precisely what you want to research. Using this technique, start with the broad topic, issue, or problem, and begin writing down all the words, phrases and ideas related to that topic that come to mind and then ‘map’ them to the original idea.

Figure 3.1 Basic concept map

This mapping technique aims to improve the “description of the breadth and depth of literature in a domain of inquiry. It also facilitates identification of the number and nature of studies underpinning mapped relationships among concepts, thus laying the groundwork for systematic research reviews and meta-analyses.” (Lesley, Floyd, & Oermann, 2002; D’Antoni & Pinto Zipp, G., 2006). Its purpose, like the other methods of question refining, is to help you organize, prioritize, and integrate material into a workable research area; one that is interesting, answerable, realistic in terms of resource availability and time management, objective, scholarly, original, and clear.

Check out this YouTube video for more basic information on how to map your research question:

In addition to helping you get started with your own literature review, the techniques described here will give you some keywords and concepts that will be useful when you begin searching the literature for relevant studies and publications on your topic.

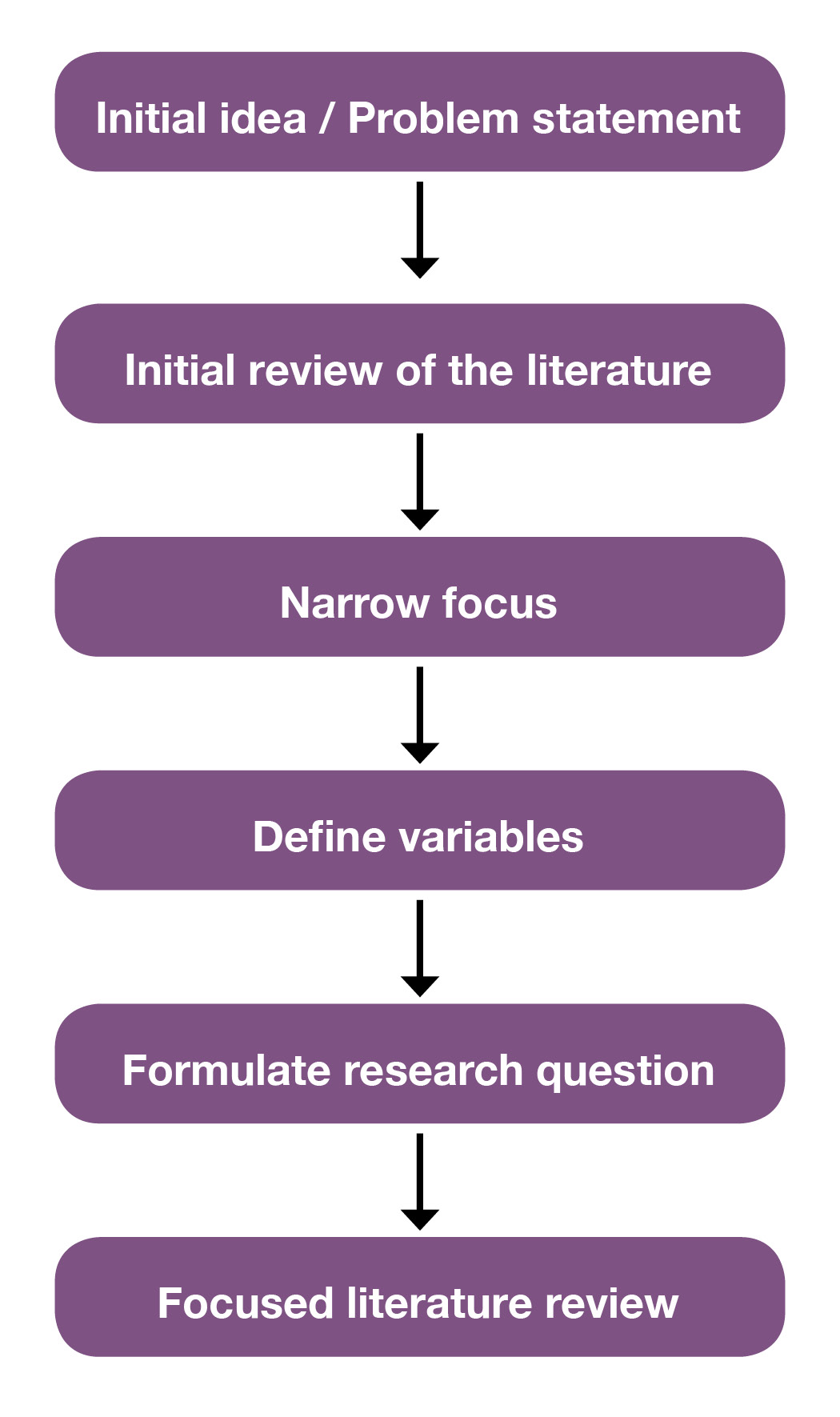

Figure 3.2 Basic literature review process

For example, perhaps your initial idea or interest is ‘how to prevent obesity.’ After an initial search of the relevant nursing literature, you realize the topic of ‘obesity’ is too broad to adequately cover in the time you have to do your literature review. You decide to narrow your focus to ‘causes of childhood obesity.’ Using PICO factors you further narrow your search to ‘the influence of family factors on overweight children.’ A potential research question might then be “What maternal factors are associated with toddler obesity in the United States?” You’re now ready to begin searching the literature for studies, reports, cases, and other information sources that relate to this question.

Similarly, for a broad topic like ‘school performance’ or ‘grades,’ and after an initial literature search that provides some variables, examples of a narrow research question might be:

Take a general topic such as “Reading Comprehension” or “Hospital Falls” and identify a slightly more narrow concept by using the questions provided in the worksheet.

Good question? | Bad question? | Why?

Each of the questions below has advantages and disadvantages. Based on some of the criteria for formulating a research question discussed in this section, which of the following questions seems the most viable for further study and why? See the Answer Key for the correct responses

Look at these recent publications in the literature for nursing and education. Can you spot the research question? Which PICO factors were used in each example?

See the Answer Key for the correct response.

I will review 30 online nursing training programs developed over a span of 10 years? Choose Yes or No

Yes or No

At the conclusion of this chapter, you will be able to:

Discovery, or background research, is something that happens at the beginning of the research process when you are just learning about a topic. It is a search for general information to get the big picture of a topic for exploration, ideas about subtopics and context for the actual focused research you will do later. It is also a time to build a list of distinctive, broad, narrow, and related search terms.

Discovery happens again when you are ready to focus in on your research question and begin your own literature review. There are two crucial elements to discovering the literature for your review with the least amount of stress as possible: the places you look and the words you use in your search.

The places you look depend on:

Review the information and publication cycles discussed in Chapter 2 to put those sources of this information in context.

The words you use will help you locate existing literature on your topic, as well as topics that may be closely related to yours. There are two categories for these words:

The words you use during both the initial and next stage of discovery should be recorded in some way throughout the literature search process. Additional terms will come to light as you read and as your question becomes more specific. You will want to keep track of those words and terms, as they will be useful in repeating your searches in additional databases, catalogs, and other repositories. Later in this chapter, we will discuss how putting the two elements (the places we look and the words we use) together can be enhanced by the use of Boolean operators and discipline-specific thesauri.

Discovery is an iterative process. There is not a straight, bright line from beginning to end. You will go back into the literature throughout the writing of your literature review as you uncover gaps in the evidence and as additional questions arise.

Let’s take some time to look at where the information sources you need for your literature review are located, indexed, and stored. At this stage, you have a general idea of your research area and have done some background searching to learn the scope and the context of your topic. You have begun collecting keywords to use in your later searching. Now, as you focus in on your literature review topic, you will take your searches to the databases and other repositories to see what the other researchers and scholars are saying about the topic.

The following resources are ordered from the more general and established information to the more recent and specific. Although it is possible to find some of these resources by searching the open web, using a search engine like Google or Google Scholar, this is not the most efficient or effective way to search for and discover research material. As a result, most of the resources described in this section are found from within academic library catalogs and databases, rather than internet search engines.

Look to books for broad and general information that is useful for background research. Books are “essential guides to understanding theory and for helping you to validate the need for your study, confirm your choice of literature, and certify (or contradict) its findings.” (Fink, 4th ed., 2014, p. 77). In this section, we will consider print and electronic books as well as print and electronic encyclopedias.

Most academic libraries use the Library of Congress classification system to organize their books and other resources. The Library of Congress classification system divides a library’s collection into 21 classes or categories. A specific letter of the alphabet is assigned to each class. More detailed divisions are accomplished with two and three letter combinations. Book shelves in most academic libraries are marked with a Library of Congress letter-number combination to correspond to the Library of Congress letter-number combination on the spines of library materials. This is often referred to as a call number and it is noted in the catalog record of every physical item on the library shelves. (Bennard et al, 2014a)

The Library of Congress (LC) classification for Education (General) is L7-991, with LA, LB, LC, LD, LE, LG, LH, LJ, and LT subclasses. For example,

LB3012.2.L36 1995

Beyond the Schoolhouse Gate: Free Speech and the Inculcation of Values

In Nursing, the LC subject range is RT1-120. A book with this LC call number might look like: R121.S8 1990 Stedman’s Medical Dictionary. Areas related to nursing that are outside that range include:

R121 Medical dictionaries

R726.8 Hospice care

R858-859.7 Medical informatics

RB37 Diagnostic and laboratory tests

RB115 Nomenclature (procedural coding – CPT, ICD9)

RC69-71 Diagnosis

RC86.7 Emergency medicine

RC266 Oncology nursing

RC952-954.6 Geriatrics

RD93-98 Wound care

RD753 Orthopedic nursing

RG951 Maternal child nursing / Obstetrical nursing

RJ245 Pediatric nursing

RM216 Nutrition and diet therapy

RM301.12 Drug guides

In most libraries, there is a collection of reference material kept in a specific section. These books, consisting of encyclopedias, dictionaries, thesauri, handbooks, atlases, and other material contain useful background or overview information about topics. Ask the librarian for help in finding an appropriate reference book. Although reference material can only be used in the library, other print books will likely be in what’s called the “circulating collection,” meaning they are available to check out.

The library also provides access to electronic reference material. Some are subject specific and others are general reference sources. Although each resource will have a different “look” just as different print encyclopedias and dictionaries look different, each should have a search box. Most will have a table of contents for navigation within the work. Content includes pages of text in books and encyclopedias and occasionally, videos. In all cases you will be able to collect background information and search terms to use later.

North American academic libraries buy or subscribe to individual ebook titles as well as collections of ebooks. Ebooks appear on various publisher and platforms, such as Springer, Cambridge, ebrary (ProQuest), EBSCO, and Safari to name a few. Although access to these ebooks varies by platform, you can find the ebook titles your library has access to through the library catalog. You can generally read the entire book online, and you can often download single chapters or a limited number of pages. You may be able to download an entire ebook without restrictions, or you may have to ‘check it out’ for a limited period of time. Some downloads will be in PDF format, others use another type of free ebook viewing software, like ePUB. Unlike public library ebook collections, most academic library ebooks are not be downloadable to ereader devices, such as Amazon’s Kindle

In general, everything owned or licensed by a library is indexed in “the library catalog”. Although most library catalogs are now sophisticated electronic products called ‘integrated library systems’, they began as wooden card filing cabinets where researchers could look for books by author, title, or subject.

While the look and feel of current integrated library systems vary between libraries, they operate in similar ways. Most library catalogs are quickly found from a library’s home page or website. The library catalog is the quickest way to find books and ebooks on your topic.

Here are some general tips for locating books in a library catalog:

OCLC WorldCat (https://www.worldcat.org/) is the world’s largest network of library content and it provides another way to search for books and ebooks. For students who do not have immediate access to an academic library catalog, WorldCat is a way to search many library catalogs at once for an item and then locate a library near you that may own or subscribe to it. Whether you will be able check the item out, request it, place an interlibrary loan request for it, or have it shipped will depend on local library policy. Note that like your own library catalog, WorldCat has a single search box, an Advanced search feature, and a way to limit by format and location.

While books and ebooks provide good background information on your topic, the main body of the literature in your research area will be found in academic journals. Scholarly journals are the main forum for research publication. Unlike books and professional magazines that may comment or summarize research findings, articles in scholarly journals are written by a researcher or research team. These authors will report in detail original study findings, and will include the data used. Articles in academic journals also go through a screening or peer-review process before publication,implying a higher level of quality and reliability. For the most current, authoritative information on a topic, scholars and researchers look to the published, scholarly literature. That said,

Journals, and the articles they contain, are often quite expensive. Libraries spend a large part of their collection budget subscribing to journals in both print and online formats. You may have noticed that a Google Scholar search will provide the citation to a journal article but will not link to the full text. This happens because Google does not subscribe to journals. It only searches and retrieves freely available web content. However, libraries do subscribe to journals and have entered into agreements to share their journal and book collections with other libraries. If you are affiliated with a library as a student, staff, or faculty member, you have access to many other libraries’ resources, through a service called interlibrary loan. Do not pay the large sums required to purchase access to articles unless you do not have another way to obtain the material, and you are unable to find a substitute resource that provides the information you need. (Bennard et al, 2014a)

A database is an electronic system for organizing information. Journal databases are where the scholarly articles are organized and indexed for searching. Anyone with an internet connection has free access to public databases such as PubMed and ERIC. Students can also search in library-subscribed general information databases (such as EBSCO’s Academic Search Premier) or a specialized or subject specific database (for example, a ProQuest version of CINAHL for Nursing or ERIC for Education).

Library databases store and display different types of information sets than a library catalog or Google Scholar. There are different types of databases that include:

Library databases are often connected to each other by means of a “link resolver”, allowing different databases to “talk to each other.” For example, if you are searching an index database and discover an article you want to read in its entirety, you can click on a link resolver that takes you to another database where the full-text of the article is held. If the full-text is not available, an automated form to request the item from another library may be an option.

Why search a database instead of Google Scholar or your library catalog? Both can lead you to good articles BUT:

Another way to find additional books and articles on your topic is to mine the reference lists of books and articles you already found. By tracing literature cited in published titles, you not only add to your understanding of the scholarly conversation about your research topic but also enrich your own literature search.

A citation is a reference to an item that gives enough information for you to identify it and find it again if necessary. You can use the citations in the material you found to lead you to other resources. Generally, citations include four elements:

For example,

For a good summary of how to read a citation for a book, book chapter, and journal article in both APA and MLA format, see this explanation at: https://www.slideshare.net/opensunytextbooks/gathering-components-of-a-citation

Conference papers are often overlooked because they can be difficult to locate in full-text. Sometimes the papers from an annual proceeding are treated like an individual book, or a single special issue of a journal. Sometimes the papers from a conference are not published and must be requested from the original author. Despite publication inconsistency, conference papers may be the first place a scholar presents important findings and, as such, are relevant to your own research. Places to look for conference papers:

Check the web sites of the organizations that sponsor conferences. Listings of conference proceedings are often under a “Publications” or “Meetings” tab/link. The National Library of Medicine maintains a conference proceedings subject guide for health-related national and international conferences. Though many papers/proceedings are not available for free, the organization web site will often contain citations of proceedings that you can request through interlibrary loan.

In addition to journal articles, original research is also published in books, reports, conference proceedings, theses and dissertations. Both theses and dissertations are very detailed and comprehensive accounts of research work. Dissertations and theses are a primary source of original research and include “referencing, both in text and in the reference list, so that, in principle, any reference to the literature may be easily traced and followed up.” (Wallace & Wray, p. 187). Citation searching of the reference list or bibliography in a dissertation is another method for discovering the relevant literature for your own research area. Like conference papers, they are more difficult to locate and retrieve than books and articles. Some may be available electronically in full-text at no cost. Others may only be available to the affiliates of the university or college where a degree was granted. Others are behind paywalls and can only be accessed after purchasing. Both CINAHL and ERIC index dissertations. Individual universities and institutional repositories often list dissertations held locally. Other places to look for theses and dissertations include:

Dissertations Express – search for dissertations from around the world. Search by subject or keyword, results include author, title, date, and where the degree was granted. Some are available in full-text at no cost, however most requirement payment.

EThOS – the national thesis service for the United Kingdom, managed by the British Library. It is a national aggregated record of all doctoral theses awarded by UK Higher Education institutions, providing free access to the full text of many theses for use by all researchers to further their own study.

Theses Canada – a collaborative program between Library and Archives Canada (LAC) and nearly 70 accredited Canadian universities. The collection contains both microfiche and electronic theses and dissertations that are for personal or academic research purposes.

Now that you have an idea of some of the places to look for information on your research topic and the form that information takes (books, ebooks, journals, conference papers, and dissertations), it’s time to consider not only how to use the specialized resources for your discipline but how to get the most out of those resources. To do a graduate-level literature review and find everything published on your topic, advanced search and retrieval skills are needed.

Literature review research often necessitates the use of Boolean operators to combine keywords. The operators – AND, OR, and NOT — are powerful tools for searching in a database or search engine. By using a combination of terms and one or more Boolean operator, you can focus your search and narrow your search results to a more specific area than a basic keyword search allows.

Boolean operators – allow you to combine your search terms using the keywords AND, OR and NOT. Look at the diagrams in Figure 4.6 to see how these terms will affect your results.

Truncation – If you use truncation (or wildcards), your search results will contain documents including variations of that term.

For example: light* will retrieve, of course, light, but also terms like: lighting, lightning, lighters and lights. Note that the truncation symbol varies depending on where you search. The most common truncation symbols are the asterisk (*) and question mark (?).

Phrase searching – Phrase searching is used to make sure your search retrieves a specific concept. For example “durable wood products” will retrieve more relevant documents than the same terms without quotation marks.

For a description of these more advanced search features, watch this short video tutorial on effective search strategies. (Clark, 2016).

It’s time to put these tips and your search skills to use. This is the point, if you have not done so already, to talk to a librarian. The librarian will direct you to the resources you need, including research databases to which the library subscribes, for your discipline or subject area. Literature reviews rely heavily on data from online databases, such as CINAHL for Nursing and ERIC for Education. Unfortunately, the costs to subscribe to vendor-provided products is high. Students affiliated with large university libraries that can afford to subscribe to these products will have access to many databases, while those who do not have fewer options.

Students who do not have access to subscription databases such as CINAHL or ERIC through Ebsco and ProQuest should use PubMed for Nursing at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/ and the public version of ERIC at https://eric.ed.gov/ for literature review research.

Although a librarian is the best resource for learning how to use a specific tool, an online tutorial on how to search PubMed may be useful and informative for those who do not have access to a librarian or a subscription database: Likewise, this document, titled “How does the ERIC search work,” provided by the Institute of Education Sciences provides some helpful tips for searching the public version ERIC.

One major source of search terms in a database is a specialized dictionary, or thesaurus, used to index journal articles. Thesauri provide a consistent and standardized way to retrieve information, especially when different terms are used for the same concept. According to Fink (2014), “evidence exists that using thesaurus terms produces more of the available citations than does reliance on key words…Using the appropriate subject heading will enable the reviewer to find all citations regardless of how the author uses the term.” (p. 24).

In Education and Nursing, thesauri are available. In subscription databases, as well as in PubMed and the public version of ERIC, look for the thesaurus to guide you to appropriate and relevant subject terms.

Citation searching works best when you already have a relevant work that is on topic. From the document you identified as useful for your own literature review, you can either search citations forward or backward to gather additional resources. Cited reference searching and reference or bibliography mining are advanced search techniques that may also help generate new ideas as well as additional keywords and subject areas.

For cited reference searching, use Google Scholar or library databases such as Web of Science or Scopus. These tools trace citations forward to link to newly published books, journal articles, book chapters, and reports that were written after the document you found. Through cited reference searching, you may also locate works that have been cited numerous times, indicating what may be a seminal work in your field.

With citation mining, you will look at the references or works cited list in the resource you located to identify other relevant works. In this type of search, you will be tracing citations backward to find significant books, journal articles, book chapters, and reports that were written before the document you found. For a brief discussion about citation searching, check out this article by Hammond & Brown (2008).

The two most important finding tools you will use are a library catalog and databases. Looking for information in catalogs and databases takes practice.

Get started by setting aside some dedicated time to become familiar with the process:

Next, complete this exercise:

At the conclusion of this chapter, you will be able to:

Searching for information is often nonlinear and iterative, requiring the evaluation of a range of information sources and the mental flexibility to pursue alternate avenues as new understanding develops. (Association of College & Research Libraries, 2016).

You developed a viable research question, compiled a list of subject headings and keywords and spent a great deal of time searching the literature of your discipline or topic for sources. It’s now time to evaluate all of the information you found. Not only do you want to be sure of the source and the quality of the information, but you also want to determine whether each item is appropriate fit for your own review. This is also the point at which you make sure that you have searched out publications for all areas of your research question and go back into the literature for another search, if necessary.

In general, when we discuss evaluation of sources we are talking about looking at quality, accuracy, relevance, bias, reputation, currency, and credibility factors in a specific work, whether it’s a book, ebook, article, website, or blog posting. Before you include a source in your literature review, you should clearly understand what it is and why you are including it. According to Bennard et al., (2014), “Using inaccurate, irrelevant, or poorly researched sources can affect the quality of your own work.” (para. 4).

When evaluating a work for inclusion in, or exclusion from, your literature review, ask yourself a series of questions about each source.

For primary and secondary sources you located in your search, use the ASAP mnemonic to evaluate inclusion in your literature review:

Is it outdated? The answer to this question depends on your topic. If you are comparing historical classroom management techniques, something from 1965 might be appropriate. In Nursing, unless you are doing a historical comparison, a textbook from 5 years ago might be too dated for your needs.

A General Rule of Thumb:

5 years, maximum: medicine, health, education, technology, science

10-20 years: history, literature, art

Check reference or bibliography sources as well as those listed in footnotes or endnotes. Skim the list to see what kinds of sources the author used. When were the sources published? If the author is primarily citing works from 10 or 15 years ago, the book may not be what you need.

Does the author have the credentials to write on the topic? Does the author have an academic degree or research grant funding? What else has the author published on the topic?

Look for academic presses, including university presses. Books published under popular press imprints (such as Random House or Macmillan, in the U.S.) will not present scholarly research in the same way as Sage, Oxford, Harvard, or the University of Washington Press.

Other questions to ask about the book you may want to include in your literature review:

In your research, it is likely you will discover information on the web that you will want to include in your literature review. For example, if your review is related to the current policy issues in public education in the United States, a potentially relevant information source may be a document located on the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) website titled The Condition of Education 2017. Likewise, for nursing, an article titled Discussing Vaccination with Concerned Patients: An Evidence-Based Resource for Healthcare Providers is available through the nursingcenter.com website. How do you evaluate these resources, and others like them?

Use the RADAR mnemonic (Mandalios, 2013) to evaluate internet sources:

How did you find the website and how is it relevant to your topic?

Look for the About page to find information about the purpose of the website . You may make a determination of its credibility based on what you find there. Does the page exhibit a particular point of view or bias? For example, a heart association or charter school may be promoting a particular perspective – how might that impact the objectivity of the information located on their site? Is there advertising or is there a product information attached to the content?

What is the web address or URL? This can give you a clue about the purpose of the website, which may be to debate, advocate, advertise or sell, campaign, or present information. Here are some common domains and their origins:

Mike Caulfield (2017), the author of Web Literacy for Student Fact-Checkers, recommends a few simple strategies to evaluate a website (as well as social media):

It is likely that most of the resources you locate for your review will be from the scholarly literature of your discipline or in your topic area. As we have already seen, peer-reviewed articles are written by and for experts in a field. They generally describe formal research studies or experiments with the purpose of providing insight on a topic. You may have located these articles through Google, Google Scholar, a subscription or open access database, or citation searching. You now may want to know how to evaluate the usefulness for your research. As with the other resources, you are again looking for authority, accuracy, reliability, relevance, currency, and scope. Looking at each article as a separate and unique artifact, consider these elements in your evaluation:

ASK: Who is the author? Is this person considered an expert in their field?

Citation analysis is the study of the impact and assumed quality of an article, an author, or an institution, based on the number of times works and/or authors have been cited by others. Google Scholar is a good way to get at this information.

Check the facts. ASK:

ASK: Is there an obvious bias? That doesn’t mean that you can’t use the information, it just means you need to take the bias into account.

ASK: The hard questions:

ASK:

To determine and evaluate in this category, ASK:

For Nursing and other medical articles ASK: