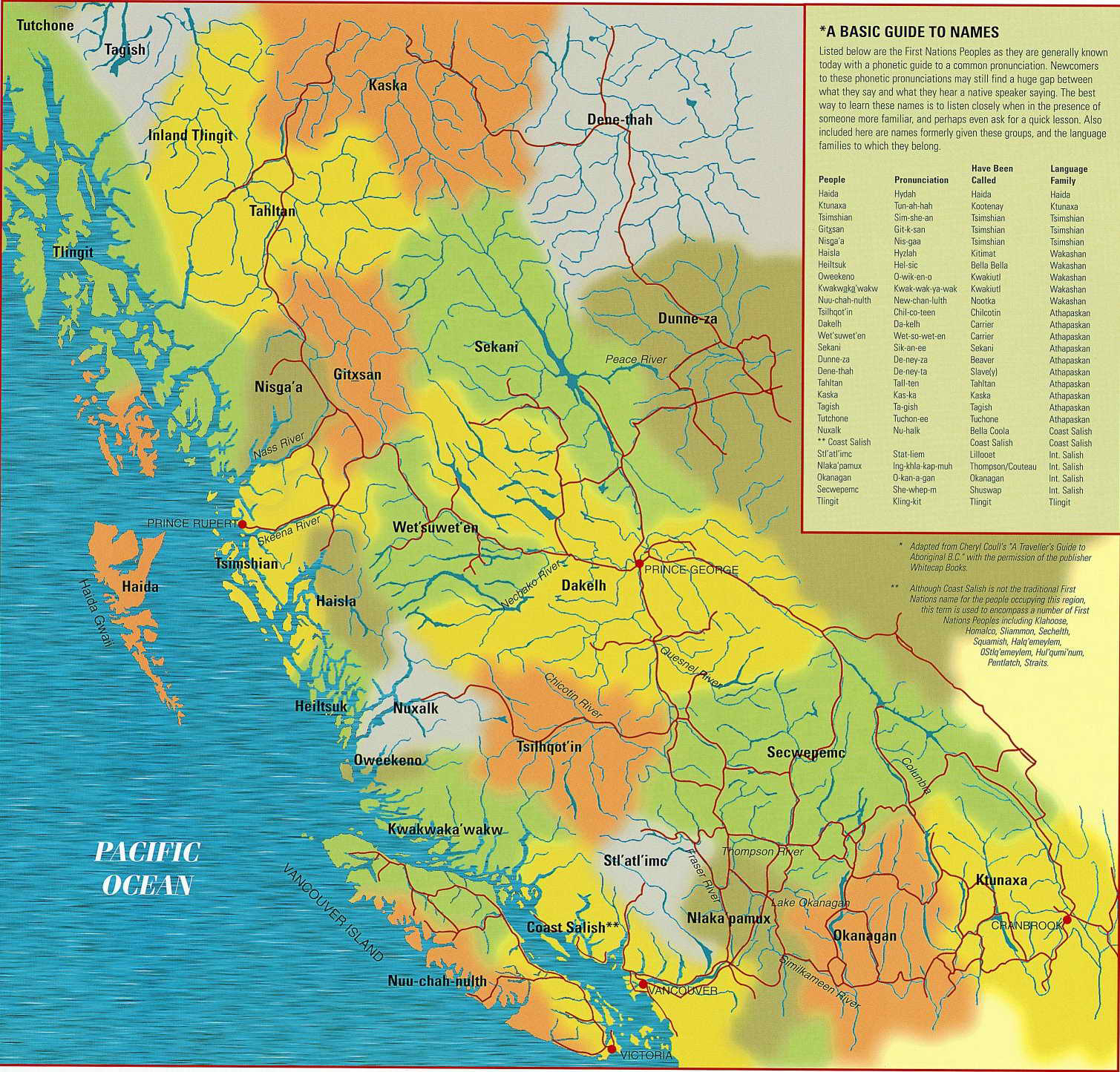

In Canada, the accepted term for people who are Indigenous and who do not identify as Inuit or Métis is First Nations. In the past, these people were referred to as “Indians.” Today, Indian is considered an offensive colonial term and should not be used.

First Nations people have lived and thrived since time immemorial on this land now called Canada. They have many different languages, cultures, traditions, and spiritual beliefs. Historically, First Nations managed their lands and resources with their own governments, laws, policies, and practices. Their societies were very complex and included systems for trade and commerce, building relationships, managing resources, and spirituality.

Today, there are around 630 different First Nation communities across Canada – about half of which are in British Columbia and Ontario. According to the 2016 Census, there are over 70 distinct Indigenous languages recognized across the country, and UNESCO’s world atlas of languages in danger recognizes over 80 distinct Indigenous languages in Canada, including those that no longer have speakers.

Frequently asked questions about First Nations

How many First Nations people are there?

First Nations make up the largest group of Indigenous Peoples in Canada. In 2016, there were 977,230 First Nations people in Canada.

Where do First Nations people live?

First Nations people live in every province and territory. The largest First Nations populations are in Ontario, British Columbia, and Alberta. However, while First Nations people living in these provinces accounted for less than 4 per cent of the total provincial populations in 2011, they represent almost one-third of the total population of the Northwest Territories and almost one-fifth of the total population of Yukon.

Do all First Nations people live on reserves?

No. Many First Nations people live off reserve. In 2011, only about half (49.3 per cent) of the 637,660 First Nations people in Canada who reported being Status Indians lived on a reserve. The numbers vary widely by province, with Quebec having the highest proportion of First Nations people living on reserve, at nearly three-quarters.

Is it okay to use the word Indian to describe First Nations people?

The term Indian refers to the legal identity of a First Nations person who is registered under the Indian Act. Indian should be used only when referring to a First Nations person with status under the Indian Act, and only within a legal context. Otherwise, the use of the term Indian in Canada is considered outdated and offensive.

You may notice that the terms American Indian and Native Indian are still in current and common usage in the United States. Some First Nations people in Canada will also refer to themselves as “Indians,” and the federal legislation is still called the Indian Act. But Indian is still not a term you should use.

What does Status Indian mean?

A person who is recognized by the federal government as being registered under the Indian Act is referred to as a “Status Indian.” Status Indians may be entitled to certain programs and services offered by federal agencies and provincial governments.

There have been many rules for deciding who is eligible for registration as an Indian under the Indian Act. Significant changes were made to the legislation in 1951, 1985 and again in 2011.

People who identify themselves as Indians but who are not entitled to registration on the Indian Register under the Indian Act are referred to as “non-Status Indians.” Some of them may be members of a First Nation even though the federal government does not recognize them as Status Indians.

Do First Nations people pay taxes?

It is a common misconception that First Nations people in Canada do not pay federal or provincial taxes.

Under certain circumstances, Status Indians can be exempted from paying tax. For example, income earned on a reserve can be tax exempt, and any goods or services purchased by a Status Indian on a reserve or delivered to them on a reserve are sales-tax exempt.

So there are limited situations where Status Indians may not have to pay income tax or sales tax. However, non-Status Indians, Métis people, and Inuit are not eligible for any tax exemptions.

Do First Nations people get free housing?

No.

There are two main categories of housing on reserve: market-based housing and non-profit social housing. Market-based housing refers to households paying the full costs associated with purchasing or renting their housing. This is not free housing!

The Canadian Mortgage and Housing Agency delivers housing programs and services to all Canadians across the country under the National Housing Act.

Do First Nations students get free post-secondary education?

Some students will and some students will not get funding for post-secondary education. It depends on the First Nation to which the student belongs and whether the First Nation has funding for the student. The demand for funding is often greater than the funds available, and some communities are in states of crisis in which they must focus their resources on other areas.

First Nations culture

Culture is an expression of a community’s worldview and unique relationship with the land. Indigenous cultures across Canada are diverse, but there are commonalities among them. Traditionally their societies have been communal, every member had roles and responsibilities, there was equality between men and women, nature was valued, and life was cyclical.

You will learn more below about other significant characteristics of First Nation cultures.

Education

Traditional Indigenous education is different from European-style education. Children learn with their families and immediate community. Learning is ongoing and does not take place at specific times. Children learn how to live, survive, participate in, and contribute to their community. They are encouraged to take part in everyday activities alongside adults to watch and listen, and then eventually practise what they have learned.

Education is a lifelong process, continuing as people grow into different roles – child, youth, adult, and Elder.

Community

Indigenous cultures are traditionally inclusive. Lynda Gray (2011), from the Tsimshian First Nation, writes: “Everyone had a place in the community despite their gender, physical or mental ability, sexual orientation, or age. Women, Elders, Two-spirit, children, and youth were an integral part of a healthy and vibrant community” (p. 32).

Elders

In Indigenous cultures, Elders are cherished and respected. An Elder is not simply an older or elderly person, but is usually someone who is very knowledgeable about the history, values, and teachings of his or her culture. He or she lives according to these values and teachings. Each Indigenous community determines who are respected Elders.

For their knowledge, wisdom, and behaviour, Elders are valuable role models and teachers for all members of the community. Elders play an important role in maintaining the tradition of passing along oral histories.

Oral traditions

First Nations pass along values and family and community histories through oral storytelling. Oral histories and stories have been passed down from generation to generation and are essential to maintaining Indigenous identity and culture. People repeat stories to keep information alive over generations. Particular people within each First Nation have memorized oral histories with great care. Indigenous cultures also tell stories and histories through symbolic objects. Carved totem poles and house posts are a good example of this kind of visual language, with a long history on the West Coast.

Ownership

Each Indigenous culture, community, and even family has its own historical and traditional stories, songs, or dances. Different cultures have different rules about ownership. Some songs, names, symbols, and dances belong only to some people or families and cannot be used, retold, danced, or sung without permission. Sometimes they are given to someone in a ceremony. Other songs and dances are openly shared.

The Potlatch

The Potlatch is the cultural, political, economic, and educational heart of First Nations along the Northwest Coast. A Potlatch may be held to celebrate births, marriages, or deaths; settle disputes; raise totem poles; or pass on names, songs, dances, or other responsibilities. Potlatches are large events that can last several days. They often include two important aspects: the host giving away gifts, and the recording, in oral history, of the events and arrangements included in the ceremony.

The Canadian government used the Indian Act to ban the Potlatch from 1884 to 1951. The government took away cultural items used in the Potlatch, such as drums, blankets, and masks. In spite of the ban, many communities continued to hold Potlatches in secret. The Potlatch continues today.

The cedar tree

Fig 1.2: A Culturally Modified Tree in Goat Rocks Wilderness, a part of Gifford Pinchot National Forest, Washington, USA.

The cedar tree is a well-known symbol among First Nation cultures along the northwest coast and is sometimes referred to as the “tree of life.” There are two kinds of indigenous cedars on the coast: red cedar and yellow cedar. The roots, boughs, bark, and trunk of the red and yellow cedar are sustainably harvested and used for cultural and practical purposes.

Some practices are shared by Indigenous cultures along the northwest coast, but each culture has its own specific traditions, uses, ceremony, and etiquette for collecting and using cedar. The people who collect cedar are careful to make sure that they do not take too much and that the tree as a species will survive. Traditionally, before a tree is cut down, the woodcutters say a prayer to thank the tree’s spirit for providing a great benefit to the people who are about to use it.

Attributions

Fig 1.2: “Culturally Modified Tree” by the US Forest Service has been designated to the Public Domain (CC0).