Glossary

5 Rs: The five tenets of the open movement: redistribute, remix, retain, reuse, and revise.

access: The ability of students, instructors, and others to obtain or gain access to education.

accessibility: The practice of creating online, digital, and print educational materials that are accessible to all, regardless of level of ability.

adapt: To customize or revise an open textbook or other open educational resource that has been released under an open-copyright licence.

adaptation: A work that has been revised or adapted. (See adapt.)

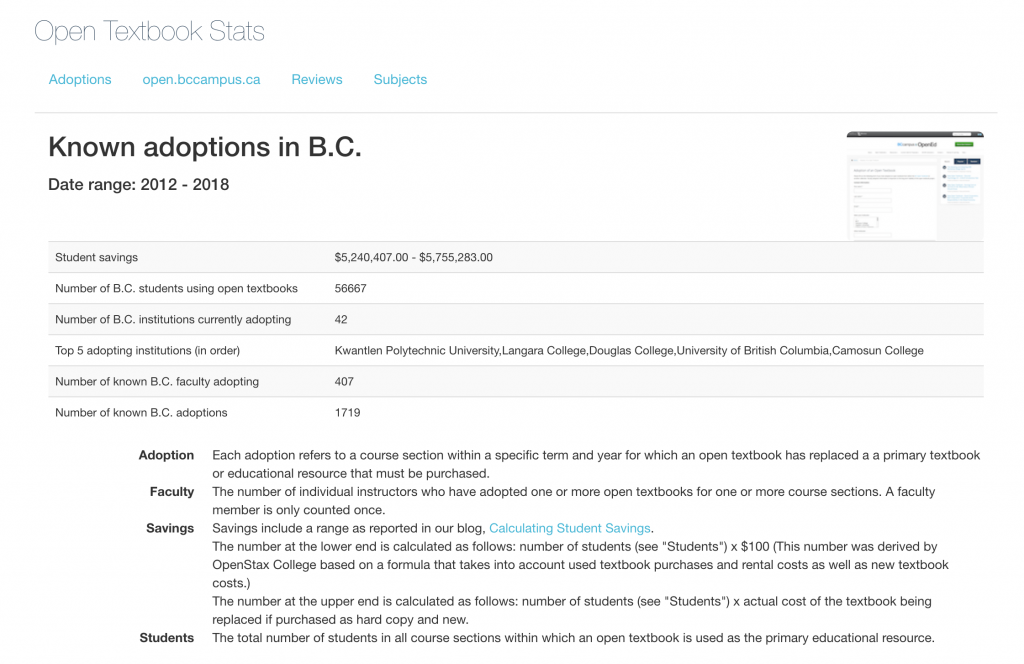

adopt: When instructors use an open textbook and/or other OERs in the classroom

adoption: An open textbook or OER that has been selected by an instructor to be used in their classroom.

Affordable Learning Georgia: A University System of Georgia (USG) [New Tab] initiative to promote student success by providing affordable textbook alternatives

APA (American Psychological Association) style: A style guide containing citation and styling information for works in the social sciences and education fields.

appendix/appendices: A part of the back matter of a book that provides supplementary material to information found in the main work.

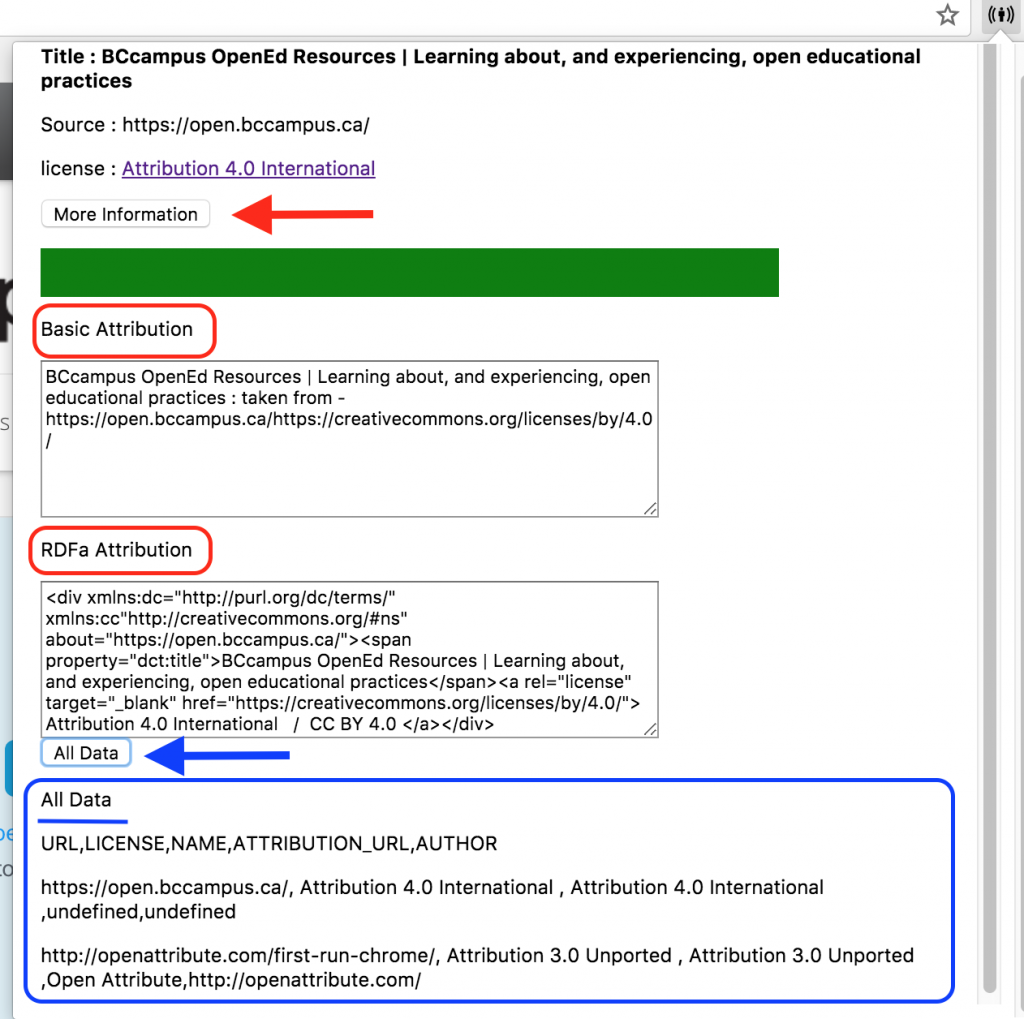

attribute: To giving credit to the creator of an original work. This the most basic requirement of a Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) licence. (See CC (Creative Commons) licence.)

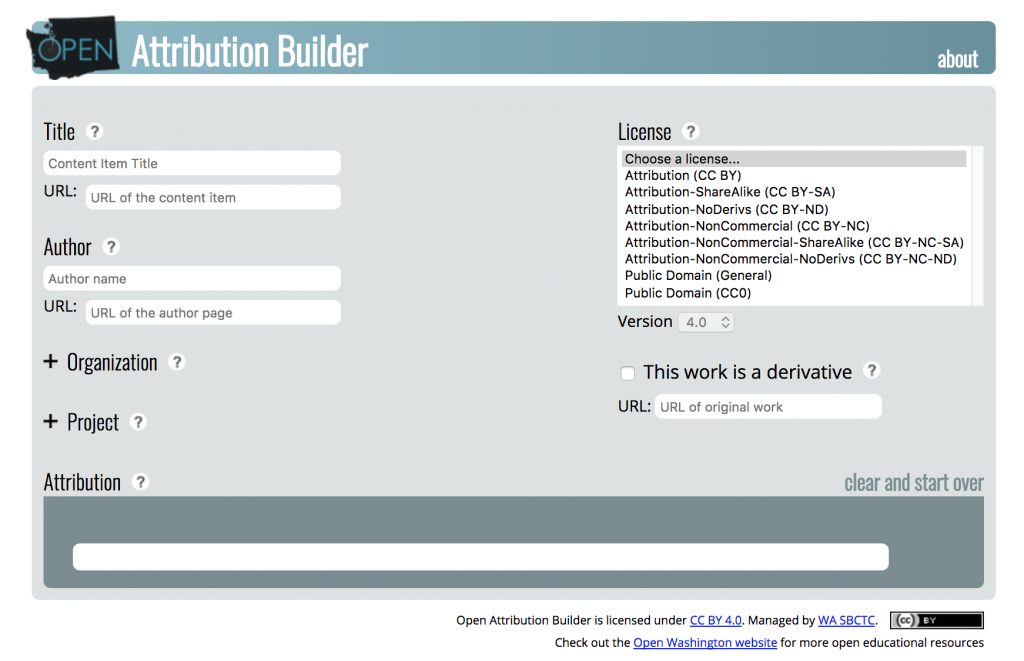

attribution statement: A line crediting the original creator of a work, which fulfills the legal requirement of open-copyright licences. The statement should include the title of the work, the name of the creator, and licence type (with links to all).

back matter: The end section of a book. It typically contains material that supplements the main text.

BCcampus: An organization supporting the post-secondary institutions of British Columbia as they adapt and evolve their teaching and learning practices to enable powerful learning opportunities for the students of B.C.

bibliography: A list of all works used as references within a textbook, both those cited and read as background in preparation for writing. In the Chicago Manual of Style, the bibliography takes the place of a reference list. (See reference list.)

Campus Manitoba/OpenEd Manitoba: An initiative by Manitoba’s Minister of Education and Advanced Learning with the goal of making higher education more accessible by reducing students costs through the use of openly licensed textbooks in Manitoba.

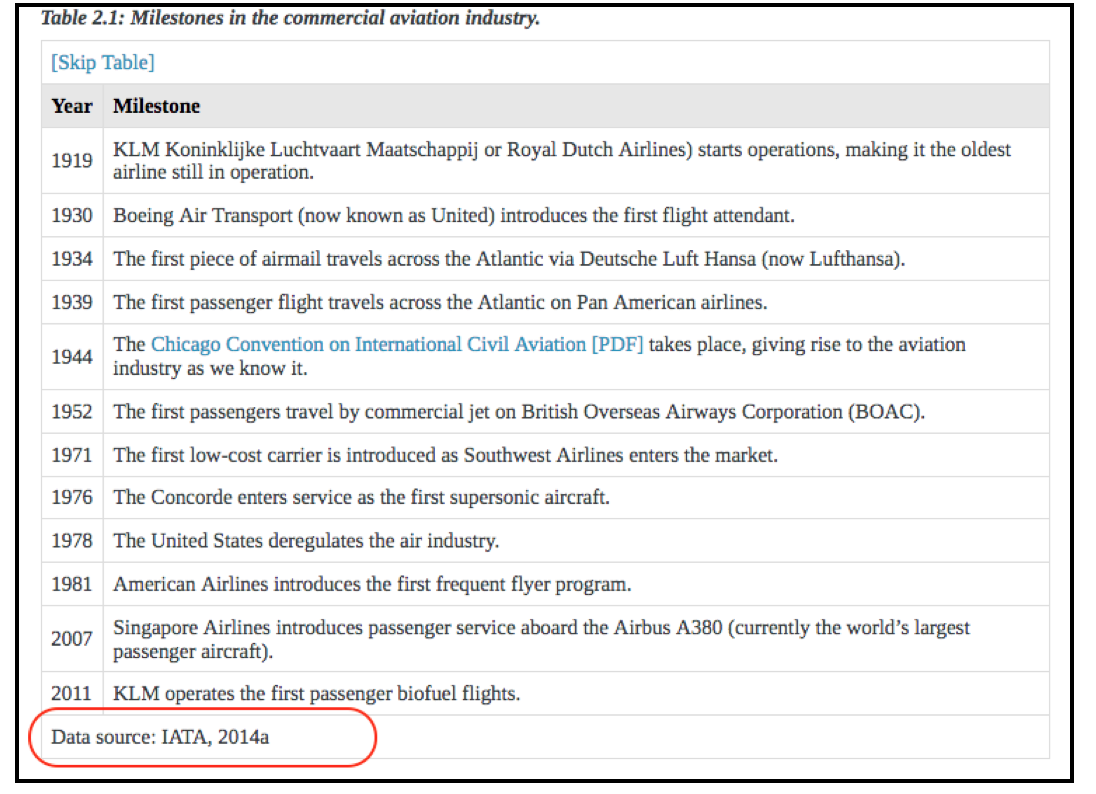

caption: Text that accompanies a figure, table, or image within a work. A caption may include the image type, the image number, a description of image, and possibly an attribution statement.

CC (Creative Common) licence: An open-copyright licence (also called a copyright licence) that allows the copyright holder to provide a defined set of permissions to their work which allow others to use, share, and change the work providing the creator of the work is given credit.

CC0 (CC zero): A tool that can be used for individuals who have dedicated their work to the public domain by waiving all of their rights to the work worldwide under copyright law, including all related and neighbouring rights, to the extent allowed by law. See public domain.

CCCOER: A growing consortium of community and technical colleges committed to expanding access to education and increasing student success through the adoption of open educational policies, practices, and resources.

Chicago Manual of Style (Chicago style): A style guide containing citation and styling information for works in the humanities. This style was developed by the Chicago University Press in 1906.

choice overload: A situation where it is difficult to make a decision because there are so many options.

citation: A method of providing the original source for information taken from a copyrighted work. The form a citation takes is generally determined by the style guide being used.

citation style: A standard for how citations should appear, either in-text or footnotes, and within the reference list or bibliography.

colophon: “A brief statement containing information about the publication of a book such as the place of publication, the publisher, and the date of publication.”

Commons: A general term often used to describe the entire body of OER and other open materials.

Connexions: A repository of open educational resources started by OpenStax where faculty, students, and others can view and share these items (https://cnx.org).

copy edit: To review and correct the grammar, spelling, punctuation, clarity, consistency, and style of a written work.

copyright: The exclusive legal right, given to an originator or an assignee, to print, publish, perform, film, or record literary, artistic, musical or other creative material, and to authorize others to do the same.

copyright infringement: To infringe (use without permission) or induce the infringement of any third-party copyrights.

copyright licence: A licence by which a licencor can grant additional copyright permissions to licencees. See open-copyright licence.

copyright notice: Information posted by the creator of a work that lists the copyright symbol (the letter C inside a circle) or the word “copyright” followed by the year in which the work was created, and the name of the copyright owner. Sometimes, a statement of rights is also included.

Creative Commons (CC): A nonprofit organization devoted to expanding the range of creative works available for others to build upon legally and to share. For more information see the Creative Commons website [New Tab].

derivative: See adaptation.

ecampus Ontario: A nonprofit corporation funded by the Government of Ontario to be a centre of excellence in online and technology-enabled learning for all publicly-funded colleges and universities in Ontario.

editable file: Files for a textbook that can be easily changed or edited. (See Editable Files.)

EPUB: A file type designed for e-readers. It can be downloaded and read on mobile devices such as smart phones, tablets, or computers. See MOBI.

erratum (Pl errata): A record of errors and their corrections for a book or other publication. Usually this statement gets its own page in the back matter. See Versioning History page.

ethnocentrism: “a tendency to view alien groups or cultures from the perspective of one’s own”

fair dealing: An exception in Canada’s Copyright Act [New Tab] that allows you to use other people’s copyright-protected material for the purpose of research, private study, education, satire, parody, criticism, review or news reporting, provided that what you do with the work is ‘fair.’

fair use: A legal doctrine defined by the U.S. Copyright Office that promotes freedom of expression by permitting the unlicensed use of copyright-protected works in certain circumstances.

figure: A label applied to an image or picture posted in an open textbook to assist with numbering (e.g., Figure 1.1.).

fixer: Someone who oversees the layout, formatting, and correct treatment of the various elements of an open textbook.

foreword: A short piece typically written by an outside expert in the field at the request of the primary author to be included in the front matter of a textbook.

front matter: The beginning section of a book placed before the main body.

GitHub: A development platform that includes open source projects such as open textbooks. For more information see https://github.com/.

HTML file (Hyper Text Markup Language): A file type designed for transferring information from one source to another.

hypothes.is: An open-source online annotation tool. For more information see https://web.hypothes.is/.

intellectual property: A form of creative effort that can be protected through a trademark, patent, or copyright.

intellectual property rights: The permissions that cover creative efforts of intellectual property, of which copyright is one.

Internet Archive: Wayback Machine: A digital archive of the World Wide Web and other information on the Internet created by the Internet Archive, a nonprofit organization based in San Francisco.

LaTeX: A program used to typeset complex scientific and mathematical notations correctly.

licence: See copyright licence.

MERLOT (Multimedia Educational Resource for Learning and Online Teaching): A curated collection of free and open online teaching, learning, and faculty development services contributed and used by an international education community. For more information see https://www.merlot.org/merlot/index.htm.

MLA (Modern Language Association of America) style: A style guide containing citation and styling information for works in the literary and humanities fields.

MOBI: A file type that can be read on a Kindle e-reader or with Kindle software. See EPUB.

OER (open educational resources): Teaching, learning, and research resources that permit free use and repurposing because they are under an open-copyright licence or because they reside in the public domain and are not copyrighted.

OER Commons: A public digital library of open educational resources launched by ISKME (Institute for the Study of Knowledge Management in Education) in 2007. For more information see https://www.oercommons.org/.

open: A term used to describe any work (written, images, music, etc.) that is openly licensed and available to the general public to reuse. See Creative Commons.

OPEN Attribution Builder: A tool to help authors create attribution statements. It was built by the Washington State Board for Community and Technical Colleges and can be found at OPEN Attribution Builder [New Tab].

open-copyright licence: A copyright licence that allows people to share, use, and edit the content of the work as long as they give credit to the original creator. See copyright licence and Creative Commons licence.

open educational resources: See OER.

Open Oregon Educational Resources: A group, also known as Open Oregon, that promotes textbook affordability for community college and university students and facilitates widespread adoption of open, low-cost, and high-quality materials for all of Oregon’s public colleges and universities.

open peer review: A review where the peer reviewer’s name, position, and institution are published along side the review. See peer review.

Open SUNY OER Services: An open access textbook publishing initiative established by State University of New York libraries and supported by SUNY Innovative Instruction Technology Grants [New Tab]. For more information see https://textbooks.opensuny.org/.

Open Textbook Network (OTN): An organization that helps higher education institutions and systems advance the use of open textbooks and practices on their campuses. It also maintains the Open Textbook Library [New Tab]. For more information see http://research.cehd.umn.edu/otn/.

Open Washington: An OER network and website dedicated to providing easy pathways for faculty to learn, find, use, and apply OER.

OpenEd Manitoba: See Campus Manitoba.

open textbook: A textbook that is released under an open-copyright licence, which permits instructors, students, and others to reuse, retain, redistribute, revise, and remix its content.

overchoice: See choice overload.

PDF (Portable Document Text): A file type designed to represent documents for easy reading, and is common format made available for downloading open textbooks.

peer review: A review of a book conducted by a subject-matter expert before or after publication. See open peer review and subject-matter expert.

plagiarize: “To steal and pass off (the ideas or words of another) as one’s own, use (another’s production) without crediting the source”

platform: An online software system or website.

Pressbooks: An open-source platform based on WordPress used to create and edit books. (See the BCcampus Open Education Pressbooks Guide [New Tab] and the Pressbooks Userguide [New Tab].)

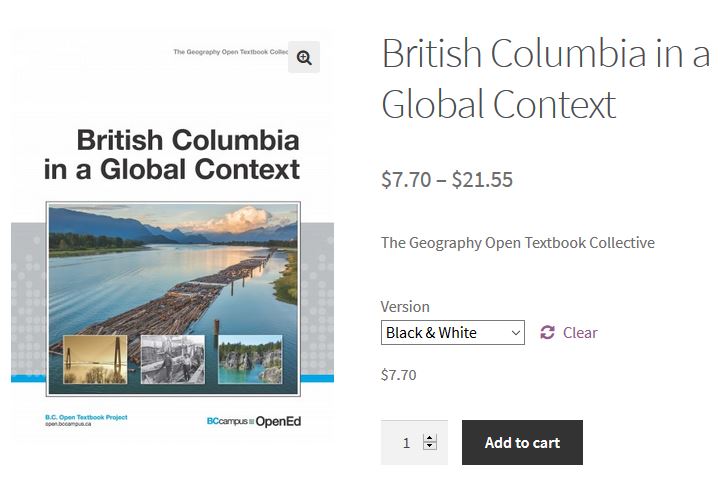

print-on-demand copy: A printed hard- or softcover and bound version of a textbook made available through a printing service for which the reader pays a price typically set only for cost recovery.

proofread: The last stage of the copy-editing process. See copy edit.

public domain: A designation for works that are not restricted by copyright. They are owned by the public, which means that anyone is allowed to use these works without obtaining permission, but no one can own them.

Public Domain Mark: Used to “mark works already free of known copyright and database restrictions and in the public domain throughout the world” See CC0 (CC zero).

public domain tools: Tools created to enable the “labeling and discovery of works that are already free of known copyright restrictions”

Rebus Community: As group made up of faculty, staff, and students from post-secondary institutions and others from around the globe who support the work of open textbook authors and projects. Their talents include copy editing, proof reading, writing, and other skills.

recto: The front side of a page.

redistribute: One of the 5 Rs of openness. It signifies the right to share copies of the original content, your revisions, or your remixes with others.

reference list: A list of all resources cited within a textbook listed them alphabetically by the authors’ last names.

remix: One of the 5 Rs of openness. It signifies the right to combine the original or revised content with other open content to create something new.

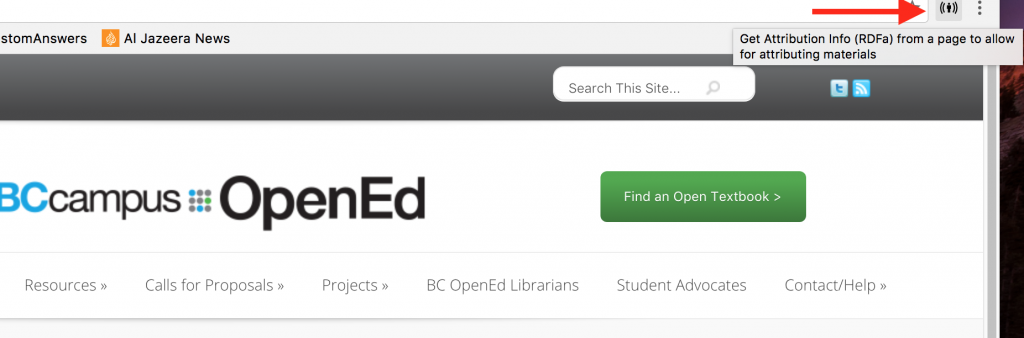

RDFa (Resource Description Framework in Attributes): A W3C recommendation that adds a set of attribute-level extensions to HTML, XHTML, and various XML documents for embedding rich metadata within web documents.

retain: One of the 5 Rs of openness. It signifies the right to make, own, and control copies of the content.

reuse: One of the 5 Rs of openness. It signifies the right to use the content in a wide range of ways and to continue using the content.

revise: One of the 5 Rs of openness. It signifies the right to adapt, adjust, modify, or alter the content itself. See adapt.

source statement: An optional statement that can be appended to an attribution statement that notes the type of source from which an open educational resource is curated, such as a museum collection. This is used when noting the source type is significant to the textbook subject matter. An example of a source statement is: This image is available from the Toronto Public Library under the reference number JRR 1059.

statement of rights: A statement that clarifies the rights permitted for a work by the copyright owner. See copyright notice.

style guide: A guide that outlines the elements that an author follows when creating or adapting a book, or other work such as spelling, word use, punctuation, citation style, measurements, and layout. See APA, Chicago Manual of Style, or MLA.

style sheet: A list or sheet that contains the elements of a book or other work that differ from the style guide. A style sheet can also list frequently used element styles for easy reference when copy editing and proofreading.

subject-matter expert (SME): An expert in the subject matter of a textbook who can provide a peer review prior to publication. See peer review.

URL: A web address. URL is short for Uniform Resource Locator.

Versioning History page: A record placed in the back matter of a digital book where minor corrections and updates are noted.

verso: The back side of a page.

write for hire: An individual who is paid to write but does not own the copyright of the work. The copyright belongs to the individual or organization who hires the writer.

XML (Extensible Markup Languag): A markup language that defines a set of rules for encoding documents in a format that is both human-readable and machine-readable. An XML file is an editable, plain-text file that helps transfer content from one format to another. See HTML.