Historical and Contemporary Realities: Movement Towards Reconciliation by Susan Manitowabi is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Historical and Contemporary Realities: Movement Towards Reconciliation by Susan Manitowabi is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

The idea behind the creation of this open textbook is twofold. First, it is written as a resource for educators to teach students about the Indigenous historical significance of the lands encompassing the Robinson-Huron Treaty area and more specifically the Greater Sudbury and Manitoulin area. Secondly, through the use of interactive mapping strategies, the textbook will serve as a guide for educators to develop a similar resource to document Indigenous stories from their own areas.

Anishinaabe is a term that is often used to describe Indigenous people from the following culturally related groups – Odawa, Ojibwe, Potawatomi, Oji-Cree, Mississaugas, Chippewa, and Algonquin peoples. For the purpose of this open textbook, when speaking of the people in the Robinson-Huron Territory, we will acknowledge them as Anishinaabe and/or Ojibwe. There are various spellings of the term ‘Anishinaabe’ depending on the place where these people reside. For example, the Union of Ontario Indians uses ‘Anishinabe’ (singular) and ‘Anishinabek’ (plural). People from Atikameksheng use the spelling Anishnawbe (singular) and Anishnawbek (plural). People from Wikwemikong, Ontario spell it with double aa’s – Anishinaabe because they have adopted the double vowel system of writing. All terms are correct, as the spelling of the Anishinaabe words varies with dialect and region.

Every effort has been made to acknowledge the various uses of the terms used to describe Indigenous peoples. The term of Indigenous is used in an inclusive way to describe the First Nations, Metis and Inuit peoples. The broader term Indigenous will be used when speaking in generalities, however, certain section of the text will use specific terms such as First Nations, Aboriginal, Anishinaabe, etc simply because that is how the people are referred to in the literature. We also acknowledge that there are other Indigenous peoples who reside in this territory such as the Cree, Mohawk, Haudenosaunee and Indigenous peoples from other territories across Turtle Island.

This open textbook is designed to be used at an introductory level to teach about social welfare issues within the Honours Bachelor of Indigenous Social Work program situated in the School of Indigenous Relations at Laurentian University. The material contained within this open textbook is broad enough that it can be used in other disciplines – sociology, education, law and justice, architecture, etc. For example, from a sociological perspective, educators may be interested in how social institutions and social relationships have changed in response to colonization and how these social institutions and relationships have evolved or remained intact with the changes within the social environment. Educators may be interested in being able to provide a more accurate description of the history as it pertains to Indigenous peoples. Law and justice may be interested in the issues related to the treaty making process, the exploitation of natural resources, or changes in legislation affecting families and communities. For those in architecture, the teachings about connection to and relationship with land may be of interest.

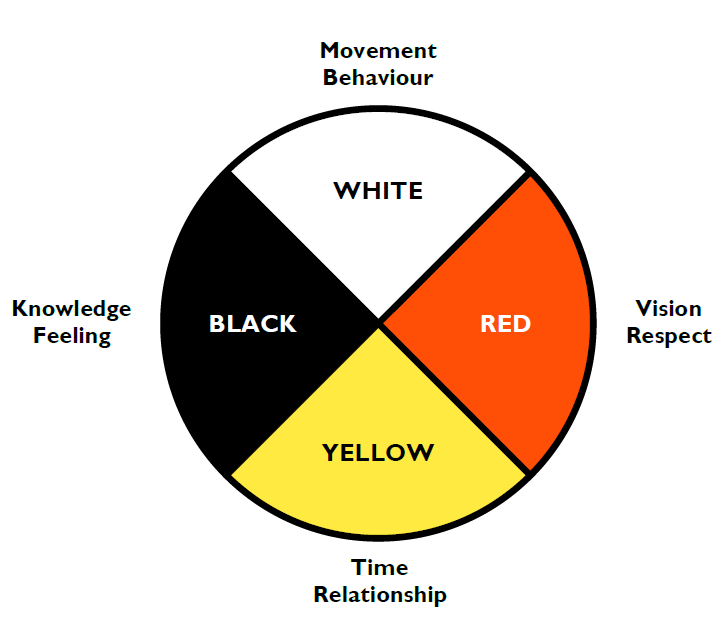

This open textbook consists of six chapters. Chapter 1 provides an introduction to the gathering of Indigenous stories and their historical significance within the Greater Sudbury area. Chapters 2 to 5 are structured using the medicine wheel as its framework. The medicine wheel is an ancient symbol conceptualized as a circle divided into four quadrants/directions, each containing teachings about how we should live our lives and the need to balance all four aspects of the being – mental, emotional, physical and spiritual (Hart, 2010; Nabigon, 2006; Hart, 2002).

This chapter introduces readers to the Indigenous stories and their historical significance within what is now known as the Greater Sudbury Area. The Greater Sudbury area is situated on the traditional territory of the Atikameksheng Anishinaabek. Chapter 1 sets the context to begin to explore the unique history of the people from Atikameksheng Anishinaabek and surrounding First Nations communities. This chapter also examines life before the arrival of the Europeans, Ojibwe culture, Ojibwe history, and teachings of the Medicine Wheel. Attention is then turned to exploring more closely two communities in the Sudbury-Manitoulin districts, namely Atikameksheng Anishinaabek and Wiigwaskinaga First Nation, in more detail.

Chapter 2 reflects the teachings of Waabanong (East) – new beginnings. According to Nabigon (2006), waabanong (the east) represents new beginnings, new life, vision, birth, food and springtime. One teaching associated with this direction is about feelings. The Medicine Wheel has two sides – positive and negative. On the positive side of the medicine wheel are good feelings and on the negative side of the medicine wheel the teachings are related to bad feelings or feelings associated with feeling inferior. These teachings help us to begin to know and understand each other. This chapter focuses on the impact of colonial history on Indigenous people and will look at colonial history including the history of pre-confederation, the treaty making process within the Robinson Huron Treaty area, as well as the impacts of legislation such as the Indian Act, the residential schools and the child welfare system on Indigenous peoples.

Chapter 3 reflects the teachings of Zhawaanong (the south) which include: time, relationships, youth, and patience. The positive side of the medicine wheel talks about creating good relationships. It takes time to build good relationships with people (Nabigon, 2006). The opposite of building good relationships is described as envy. When people are envious, they are said to want to have what others have but are not willing to work for them. Therefore, to build good relationships, one must work for it. This chapter explores how Indigenous peoples have resisted colonization and describes the efforts made by Indigenous people to revitalize language, culture, traditional healing practices, traditional governance and Indigenous ways of being. Additionally, this chapter will look at how Indigenous people have worked to create spaces for people to learn about traditions and culture, traditional healing practices, Indigenous governance systems, Indigenous knowledge systems and Indigenous ways of being. This is reflected in organizations such as the development of the Friendship Centre, Shkagamik-kwe Health Centre, Kina Gbezghomi Child and Family Services, the School of Indigenous Relations, etc. Learning about the scope of services that are available to Indigenous peoples of this territory and the ways that these services have been able to respond to the impacts of colonial history can create a sense of pride in Indigenous students, faculty and staff and de-mystify some of the stereotypes that exist about Indigenous peoples, programs and services.

Chapter 4 reflects the teachings that lie in Epingiishmag (the western) direction – which is one of respect and reason (Nabigon, 2006). According to Nabigon (2006), the word ‘respect’ is made up of two words from the English language –‘re’ meaning again and ‘spect’ meaning to look at. When we meet people for the first time we develop a first impression of them but we do not develop ‘respect’ for them until we get to see them for a second time. To gain respect for someone we need to get to know them at a deeper level. The second teaching is about reason. Reason refers to the ability to think, comprehend and understand. This chapter builds upon the previous chapter in that the students are learning at a deeper level about traditions, culture and healing practices, Indigenous governance systems and Indigenous ways of knowing and being. Having this deeper understanding leads to a greater appreciation of the specific needs of Indigenous peoples. This provides the foundation for Indigenous/non-Indigenous to understand the cultural teaching, healing practices and ways of knowing and being, thereby creating space for reconciliation to occur. This chapter builds a deeper understanding of the relationships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples.

Chapter 5 reflects the teachings of Giiwedinong (North) – caring, wisdom, movement and action (Nabigon, 2006). Elders are represented in the northern direction. Elders are respected for their life history, experiences and wisdom and have reached a point in their lives where they are able to share their gifts and knowledge with others. This chapter encourages students to reflect on their own understanding of colonial history; the services and programs that have developed in response to that history; their own knowledge of cultural teachings, healing practices and ways of knowing and being and how they are going to incorporate what they have learned into some action that can lead to reconciliation. This chapter encourages self-reflection about what has been learned up to this point and challenges one to take action towards reconciliation. How do we move forward? What lies in the future? What new initiatives can be developed that help with the braiding of Indigenous and Western approaches.

The last chapter focuses on the centre of the Medicine Wheel – the fire within or, the self. Each individual has a responsibility to oneself – to feed the inner spirit. This chapter is about braiding Indigenous and Western approaches and one’s responsibility to retell the story of colonial history. This brings the book back full circle to the beginning of the book where we looked at the gathering of Indigenous stories and their historical significance within the Greater Sudbury area. Whether you are Indigenous or non-Indigenous, this part of the book course allows you look to the future and tell another story about the relationship between Indigenous/non-Indigenous people of this territory.

In each chapter, you will begin with a chapter overview and list of chapter learning outcomes. It’s important to keep these outcomes in mind as you read through the chapter.

Throughout each chapter, you will also find:

Learning Activities which provide you with an opportunity to test your knowledge;

Expand your Knowledge sections, which provide you with websites and additional resources;

Interesting Facts boxes to share additional facts about the topic or area being discussed

You will also find electronic maps throughout the text, which situate the stories and provide both geographical and visual context and reference for the reader.

If you adopt this book, as a core or supplemental resource, please report your adoption in order for us to celebrate your support of students’ savings. Report your commitment at www.openlibrary.ecampusontario.ca.

We invite you to adapt this book further to meet your and your students’ needs. Please let us know if you do! If you would like to use Pressbooks, the platform used to make this book, contact eCampusOntario for an account using open@ecampusontario.ca.

If this text does not meet your needs, please check out our full library at www.openlibrary.ecampusontario.ca. If you still cannot find what you are looking for, connect with colleagues and eCampusOntario to explore creating your own open education resource (OER).

eCampusOntario is a not-for-profit corporation funded by the Government of Ontario. It serves as a centre of excellence in online and technology-enabled learning for all publicly funded colleges and universities in Ontario and has embarked on a bold mission to widen access to post-secondary education and training in Ontario. This textbook is part of eCampusOntario’s open textbook library, which provides free learning resources in a wide range of subject areas. These open textbooks can be assigned by instructors for their classes and can be downloaded by learners to electronic devices or printed for a low cost by our printing partner, The University of Waterloo. These free and open educational resources are customizable to meet a wide range of learning needs, and we invite instructors to review and adopt the resources for use in their courses.

Much like the Creation stories of Aboriginal peoples, this chapter lays the foundation for what follows in this and the subsequent chapters. Aboriginal people were the first to be placed on this land by the Creator. As the original inhabitants, Aboriginal peoples have a special relationship to the land and their connection to the land forms part of their identity as a people. Aboriginal people believe they had and still have inherent rights to the lands they occupied prior to the arrival of the Europeans. These rights include the continued habitation and use of the land for hunting, fishing, trapping, gathering food and medicines, and other traditional uses (Aboriginal Justice Implementation Commission, 1999).

Aboriginal peoples occupied North America long before the arrival of Europeans to this land. The Royal Proclamation of 1763 recognized the pre-existing rights of Aboriginal peoples to their territories. According to the Aboriginal Justice Implementation Commission (1999), when Europeans first arrived in North America, they did not have the same rights as the original inhabitants of this land. As outsiders, they would have to seek permission from the original inhabitants for permission to share in the land and its resources.

This chapter begins by situating the First Nations peoples within their traditional territories in and around the Greater Sudbury and Manitoulin areas. A description of the original geographical territories of Atikameksheng Anishnawbek and Whitefish River First Nations is provided.

The Medicine Wheel teachings provide guidance for how to live our lives in a good way – mino bimaadiziwin. The Medicine Wheel teachings contain the values and principles for how we should conduct ourselves. These teachings recognize that we are all human beings and recognize the relationship that human beings have to each other, to all other beings and to other than human beings – hence the saying ‘all my relations.’ This section of the chapter explores the Medicine Wheel teachings further with the aim of creating a greater understanding of the significance that these Medicine Wheel teachings have for Indigenous peoples and their relationships within the cosmos.

The next section of this chapter explores Ojibwe peoples and their history. This takes us back to a time when European peoples were just arriving in this country. The dynamics between the Indigenous peoples of these territories and other Indigenous territories were greatly affected by the arrival of the European people. Indigenous peoples welcomed the Europeans to this country and provided a great deal of help to them especially since many of the European people were sick and starving. As time progressed, relationships between the Indigenous people and non-Indigenous people became more formalized. Relationships with Indigenous peoples were crucial to the expansion westward and to the opening of the fur trade into the west. In addition, it is also noted that the Métis played a significant role in the expansion of the fur trade westward particularly because of their unique cultural background being of both French Canadian and Native descent and being skilled hunters, traders, voyageurs and interpreters (Canada’s First Peoples, n.d.).

We now turn our attention to the traditional territories within the Robinson Huron Treaty areas. Aboriginal peoples occupied this territory long before it become known as the Robinson-Huron Treaty area.

When you have worked through the material in this chapter, you will be able to do the following:

The map provided below illustrates the locations of the First Nations territories in the Lake Huron Region. The City of Sault Ste Marie is located on the traditional territory of the Ojibwes of Garden River. The town of Manitowaning is located close to Wikwemikong Unceded Indian Reserve. Mindemoya is located close to M’Chigeeng First Nation and Little Current is close to Ojibwes of Aundek Omni Kaning. This etextbook focuses mainly on the traditional territory of the Atikameksheng Anishnawbek, the land upon which the City of Greater Sudbury is situated. The other territory of focus is Wiigwaskinaga (Whitefish River) First Nation as small community that lies between Espanola and Little Current, Ontario.

Did you know…

The word “Anishinabe” can be spelled differently (Anishnaabe, Anishnawbe), most likely attributed to dialect differences. There are several variations in the translations such as “first man,” “original man,” or “good person,” but the intent is similar. Similarly, the plural, Anishinabeg or Anishinaabeg, means “first people.” There are also variations in spelling from one territory to the next. For example, The Union of Ontario Indians uses ‘Anishinabe’ (singular) and ‘Anishinabek’ (plural). People from Atikameksheng use the spelling Anishnawbe (singular) and Anishnawbek (plural).

Atikameksheng Anishnawbek is located approximately 19 km west of the City of Greater Sudbury. Although the City of Greater Sudbury is situated on the traditional territory of the Atikameksheng Anishnawbek, the community itself now has a land base of 43,747 acres. There are eighteen lakes within the current land base and the community itself is surrounded by eight lakes. The community is comprised of approximately 1220 members. Atikameksheng Anishnawbek belongs to the following political organizations:

Whitefish River First Nation (WRFN) also known as “Wiigwaaskingaa” (and formerly known as Birch Island) is located on Highway 6 between Espanola and Little Current, Ontario. The community has a membership of approximately 1,200 citizens with 440 members residing in the village of Whitefish River. This community, located on the shores of Georgian Bay and the North Shore Channel, serves as the gatekeeper to Manitoulin Island, Ontario. WRFN is represented provincially by the Union of Ontario Indians (UOI) and the Chiefs of Ontario (COO) and nationally by the Assembly of First Nations (AFN).

Click on the image of the map below for a more detailed geographic context.

Indigenous peoples have their own versions of origin stories. These stories are in conflict with the western understandings of the world. Western science insists on the theory of Asian origins and that Bering Strait theory accounts for how Indigenous people came to exist in North America (Brownlie, 2009). Indigenous people have their own versions of how they came to exist in North America.

Indigenous people refer to North America as ‘Turtle Island.’ There are many versions of the ‘Creation Story’ that describe how ‘Turtle Island’ was created; the stories will vary from one community to another but the gist of the story is pretty similar. One version of the story is that the Creator placed Anishinaabe on the Earth. As time went on, the original people started to fight with one another. The Creator decided to purify the Earth and sent a great flood. Only NanabushMany Ojibwe legends speak about Nanabush. Nanabush is half spirit/half human (born to an Anishinaabe-kwe (an Aboriginal woman) and a spirit being) giving him the powers of the spirit and the virtues and flaws of a human being. It is said that Nanabush was sent to teach the Anishinaabek how to live but his inability to control his humanly wants and needs often gets him into trouble. Nanabush stories are about humorous escapades and great adventures that either saves the Anishinaabek or causes them great hardship (Ojibwe Cultural Foundation, n.d.) and a few animals remained. The Creation story describes how Nanabush worked with the animals to re-create a new world. Creation stories contain teachings about the importance of connection to the land (the natural environment) and all of creation. Basil Johnson’s (1976) version of the story talks about Sky-Woman (the original human) who survives and comes to rest on the back of a great turtle. The following excerpt is from Basil Johnson’s account of the Creation story:

Gladly, all the animals tried to serve the spirit woman. The beaver was the first to plunge into the depths. He soon surfaced out of breath and without the precious soil. The fisher tried, but he too failed. The marten went down, came up empty handed, reporting the water was too deep. The loon tried. Although he remained out of sight for a long time, he too emerged, gasping for air. He said that it was too dark. All tried to fulfill the spirit women’s request. All failed. All were ashamed.

Finally, the least of the water creatures, the muskrat, volunteered to dive. At this announcement the other water creatures laughed in scorn, because they doubted this little creature’s strength and endurance. Had not they, who were strong and able, been unable to grasp the soil from the bottom of the sea? How could he, the muskrat, the most humble among them, succeed when they could not?

Nevertheless, the little muskrat volunteered to dive. Undaunted, he disappeared into the waves. The onlookers smiled. They waited for the muskrat to emerge as empty handed as they had done. Time passed. Smiles turned to worried frowns. The small hope that each had nurtured for the success of the muskrat turned into despair. When the waiting creatures had given up, the muskrat floated to the surface more dead than alive, but he clutched in his paws a small morsel of soil. Where the great had failed, the small succeeded. (Johnson, 1976, p.14)Excerpted from Ojibway Heritage by Basil H. Johnston. Copyright © 1976 by McClelland & Stewart. Reprinted by permission of McClelland & Stewart, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited.

Aboriginal worldview is grounded in the Creation story. Aboriginal people view the earth as their Mother and the animals as their spiritual kin. There is an interconnectedness between all living things and we are all part of a greater whole which is called life. Aboriginal worldview is expressed through the symbol of the circle. The circle is the first design Gchi-Manido drew on the darkness of the universe before creation began (Partridge, 2010). All life begins in the east and progresses around the circle and “…all life maintains and operates within this circular and cyclical pattern” (Partridge, 2010, pg. 38). All life is cyclical – human and non-human life operates in this circular fashion (Dumont, 1989; Black Elk, in Black Elk Speaks as told through John G. Neihardt, 2014). Aboriginal culture recognizes natural law. Time was marked by the changing seasons and the rising and setting of the sun, rather than by numbers, and their existence was marked by an acceptance of and respect for their natural surroundings and their place in the scheme of things. The thinking of Aboriginal peoples was cyclical, rather than linear like that of the Europeans. Everything was thought of in terms of its relation to the whole, not as individual bits of information to be compared to one another. Aboriginal philosophy was holistic, and did not lend itself readily to dichotomies or categories as did European philosophy. So, for Aboriginal people, their rights were—and still are—seen in broad, conceptual terms (Aboriginal Justice Implementation Commission, 1999).

There are many versions of medicine wheel teachings. These teachings vary from one community to another but there are some foundational concepts that are similar between the various medicine wheel teachings. For example, Medicine Wheels are usually depicted through four directions but also include the sky, the earth and the centre. For Ojibwe people, the colours are yellow (east), red (south), black (west), white (north), Father Sky (blue), Mother Earth (green) and the self (Centre, purple). The medicine wheel reminds us that everything comes in fours – the four seasons, the four stages of life, the four races of humanity, four cardinal directions, etc. The seven stages of life and the seven living teachings (Benton-Banai, 2010) are also represented by these seven directions. According to Toulouse (2018), it was not until the 1960s that the use of colours (red, yellow, black, white, blue, green) appeared in contemporary medicine wheels. Traditional medicine wheels (sacred circles) were often depicted using stones set out in the form of a wheel and included at least two of the following three traits: (1) a central stone cairn, (2) one or more concentric stone circles, and/or (3) two or more stone lines radiating outward from a central point (Royal Alberta Museum, 2018). Indigenous people used medicine wheels to mark significant locations such as places of energy, spiritual and ceremonial grounds, as well as meeting locations, places of meditation, teaching and celebration (Pereda, n.d.).

“All parts of the wheel are important and depend on each other in the cycle of life; what affects one affects all, and the world cannot continue with missing parts. For this reason, the Medicine Wheel teaches that harmony, balance and respect for all parts are needed to sustain life” (Elder Lillian Pitawanakwat, Ojibwe/Potawotami, as cited in Pereda, n.d.)

The circle describes various aspects of life, both seen and unseen. It provides us teachings about how to live life in a good way. Aboriginal people understand the connection to creation and all living things. The four directions remind us of the need for balance in our lives and that we must work on a daily basis to strive for that balance. The following teachings are a synopsis of the medicine wheel teachings provided by Lillian Pitawanakwat-Ba from Whitefish River First Nation (Four Directions, 2006).

According to Pitawanakwat (as cited in Four Directions Teaching, 2006), the centre represents the fire within and our responsibility for maintaining that fire. Pitawanakwat recalls that as a child, her father would ask at the end of the day, “My daughter, how is your fire burning?” In recalling the events of the day, she would reflect on whether she had been offensive to anyone, or whether or not she had been offended. This was an important part of nurturing the fire within as children were taught to let go of any distractions of the day and make peace within ourselves in order to nurture and maintain that inner fire.

The story of the Rose, as told by Pitawanakwat (2006), serves as a reminder of the value of nurturance and the essence of life. According to this story, the Creator asked the flower people, “Who among you will bring a reminder to the two-legged about the essence of life?” The buttercup offered but the Creator refused on the basis that the buttercup was ‘too bright.’ All of the flowers offered their help but were refused. The rose finally offered, stating “Let me remind them with my essence, so that in times of sadness, and in times of joy, they will remember how to be kind to themselves.” So the Creator, planted the seed of the rose and as it grew a little, it sprouted very, very sharp little thorns and eventually it bloomed into a full rose. This teaching reminds us that life is like a rose with the thorns representing life’s journey; the experiences that make us who we are and the rose representing the many times in life when we decay and die only to bounce back again through reflection, meditation, awareness, acceptance and surrender.

According to Pitawanakwat (as cited in Four Directions Teachings, 2006), the springtime, and the spring of life are represented in the east. All life begins in the east; we begin our human life as we journey form the spirit world into this physical world. When we are born into this physical world, the Creator grants four gifts: to pick our own mother and father, and how we are to be born and die. The spirit enters the physical level at conception and is carried in its mother for nine months. When the mother’s water breaks, the spirit enters into the physical world.

The teachings from the east remind us that all life is spirit (the wind, earth, fire, and water – all those things that are alive with energy and movement) and that to honour that life, we offer tobacco in thanksgiving. Prayers of thanksgiving honour all those things that we cannot exist without, for the breath of life, the cycles of time and to be grateful for life. We are especially grateful for natural law. All our teachings come from the natural world around us.

The summer and youth are represented in the southern direction. Summer is a time of continued nurturance. Youth are at a stage in life where they are no longer children and are not quite adults. They may be searching for what they had to leave behind in their childhood and also struggling with their identity. Who am I? Where do I come from? Youth are in the wandering stage of life – wandering and wondering about life. In this direction, we are reminded to look after our spirits by finding that balance within ourselves and to pay attention to what our spirit is telling us. If we listen to our intuition, then the spirit will help to keep us safe. Youth who grow up without spirit nurturance have no direction and are at risk of being exposed to all kinds of dangers and distractions; their spirits have not been nurtured. Youth often search for those people that can provide that nurturance such as Elders. They are starved for the teachings, especially those teachings that provide meaning and purpose. Youth need nurturance, guidance and protection to help them through this transitional phase of their lives.

As youth begin to journey into the next stage of life, they begin to become more accountable and start the planning stage of their lives – planning to be parents, to have a career, etc.

The western direction represents the adult stage of life. Death is also represented in this direction. Death comes in many forms – the end of our physical journey and crossing back into the spirit world; the setting sun and end of the day; or recognition that as old thoughts and feelings die, new ones emerge.

The heart is also represented in the west. The heart helps us to evaluate, appreciate and enjoy our lives. By nurturing our hearts, we create balance in our lives.

The teachings of the north remind us to slow down and rest. The north is referred to as the rest period, a time to be respectful of the need to care for and nurture the physical body. It is also referred to by some as a period of remembrance – a time for contemplation of what has happened in life. Winter is represented in the north – it is a time for rest for the earth. It is also a time of reflection – on being a child, a youth and an adult. Elders, pipe carriers and the lodge keepers, reside in the north. Their teachings help us to embrace all aspects of our beings so that we can feel and experience the fullness of life. Wisdom also resides in the north. Elder’s share their stories in the winter months.

Pitawanakwat relates the story of the first sweat lodge ceremony that happened at Dreamer’s Rock, a sacred place in the Whitefish River First Nation territory, after the ban was lifted that prohibited ceremonies from taking place there. It was at this time that Pitawanakwat was reminded that the spirits (ancestors) were hungry and that they needed to be fed. This was when she organized a community feast and prepared a spirit plate. She offered her tobacco and prayed:

“Grandfathers, grandmothers, ancestors, all our relations: please hear us. We

are here now, have pity on us. We had forgotten to feed you. You have lived a

long time without food, and now we are here to honour you. Please come and

feast with us.” (Pitawanakwat as cited in Four Directions Teachings, 2006)

For Pitawanakwat, this is when she became reconnected to the circle and to her ancestors, and was reminded of her responsibility to nurture her inner spirit and to acknowledge the beauty of the original teachings.

Did you know…

Turtles are featured in many folktales the world over. African folklore views the turtle as the smartest animal. The turtle is viewed as a very powerful symbol in Chinese mythology. For the Lakota, the turtle (ke-ya) spirit symbolizes health and longevity (turtle symbols contained within medicine bags are believed to protect and prolong life). The earlier traditions of the tribe put a beaded turtle on the umbilicus or the crib of newborn girls for protection and long life.

There are similarities in the values and beliefs of all Indigenous peoples across this great territory now known as Canada, yet at the same time there is great diversity in their ways of life, their languages and their relationships with one another. These differences can be attributed in part to the traditional territories in which they live. For example, Indigenous people who live in the far north have had to adapt to the harsher environmental conditions and the resources they have access to are different from those who live in the southern parts of the country.

Long before the arrival of the Europeans, Indigenous peoples lived as distinct societies. Each had their own territorial boundaries; teachings on how to live in harmony with the land they inhabited, language, customs and belief systems, educational system, governance, and common identity. They had their own trade networks and trading routes. They had also developed their own alliances and treaties with each other. These alliances and treaties were formalized through the use of pipe ceremonies and these understandings were documented through the use of a wampum belt.

“Ojibway forms of law, government and social control revealed their superior rationality: their institutions operated through appeal to reason, not coercion, and were more effective than European approaches for maintaining social peace” (Copway (1850) cited in First Nations, First Thoughts, 2009).

The Assembly of First Nations (AFN) has created ‘A Declaration of First Nations’ that describes the relationship that the Original Peoples of this land have with the Creator, the laws that govern their relationship to nature and mankind, as well as their rights and responsibilities with respect to the land they live on. This declaration recognizes their distinct spiritual beliefs, language and culture, and relationship to the land.

Recorded history estimates that the Ojibwe occupied the territories around the Great Lakes as early as 1400, expanding westward until the 1600s (Sultzman, 2000). The Ojibway people were the largest and most powerful of all the tribes inhabiting the Great Lakes region of North America. Despite the fur trade and Indian wars, the Ojibwe peoples continued to expand their territories and by the 1800s they occupied lands in Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Michigan, Minnesota, Michigan, North Dakota, Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio. According to Sultzmann (2000), white settlement forcibly removed the Ojibwe from their lands and onto reservations.

Most Ojibwe belong to a cultural grouping known as the Woodlands culture. The Ojibwe people inhabit a great area around the Great Lakes and some have migrated to the plains or to areas further south. This has resulted in the need to adapt to different environmental conditions, which has influenced aspects of life such as art, ceremony and dress. For example, the Ojibwe that migrated towards the southern regions of their territories – Michigan, Illinois, Wisconsin, and Ontario – were able to establish larger, more permanent villages and began to cultivate plants such as corn, beans, squash, and tobacco. The Ojibwe people who lived in the northern Great Lakes region had a shorter growing season and poor soil so tended to rely on hunting and gathering for their food sources. They would harvest wild rice and maple sugar. Woodland Ojibwe were skilled hunters and trappers as well as fishermen. Ojibwe people still engage in hunting, trapping and fishing practices although their methods may have changed over the years.

The Ojibwe were very resourceful using what was available from their environment as building materials and for household items. For example, birch bark was used for almost everything: utensils, storage containers, and canoes. Birch bark was also used as a building material to cover the wigwam. It was an excellent building material because it was sturdy, lightweight and portable so that when the family moved it was easy to disassemble their wigwam and re-assemble it in their new location.

Clothing and moccasins were made from the hide of animals, particularly deer and moose, which also served as their food sources. During the winter months, the Ojibwe spent much of their time inside the wigwams. The winter was a time of storytelling and for working on their clothing. The women would decorate their moccasins with quill and moose hair designs, often taking designs from the environment such as floral patterns that are distinctive to the woodland people.

Ojibwe life was centered around the land and the seasons. For example, in the winter months the tribe would separate into their extended family units and travel to their hunting camps. In this way, they could hunt in a specific territory without competition from other hunters and ensure that over-hunting would not occur. In the summer, they would return to their summer homes where fish, wild rice and berries were abundant.

The Greater Sudbury area is situated on the traditional territory of the Atikameksheng Anishnawbek. Like many traditional territories, Atikameksheng has its own stories related to the land and environment that existed long before the arrival of settlers to this area. They had their own system of governance, their own educational systems, their own stories, their own ways of knowing and being and their own ways of relating to the land around them and to the Anishnawbek from surrounding traditional territories. All of this contributes to the unique identity of the peoples from this traditional territory. Similarly, each First Nation community in the surrounding Anishnawbek territories have their own history and stories that set them apart from each other but there are also many similarities between the peoples of the Anishnawbek territories.

The Atikameksheng Anishnawbek are descendents of the Ojibwe, Algonquin and Odawa Nations. In 1850, Chief Shawenekezhik, on behalf of the Atikameksheng Anishnawbek, signed the Robinson-Huron Treaty, granting the British Crown and their people (Royal Subjects) a right to occupy and share the lands of the Anishnawbek. The Robinson-Huron Treaty will be discussed in the next chapter. The Anishnawbek have a special relationship to the land that can be difficult for non-Indiegnous people to understand.

The following excerpt from an Interview with Art Petahtegoose from Atikameksheng Anishnawbek describes the relationship between the Anishnewbek and land including animal and plant life:

At the time when the white man came, was a time when the mind of the Anishnawbek was knowing that language carries within it what the people were living. When we take a look at gift giving and we go out to harvest the moose, go out to harvest the bear, go out to harvest the berries, and go out to harvest the fish, the animal and the berry in being harvested one must not view it as one being more important than the other and that is what you see in the living Anishinabe people. If you’re going to go out to harvest berries there is a need to give tobacco, there is a need to give medicine in return for the taking of that life. When you are looking at land as being a form of life, and look at concepts of death, we really don’t see death we see life giving life. My life is coming from that fish, my life is coming from that plant, my life is coming from that water, so that object is carrying life within it which is able to nurture me (Art Petahtegoose, personal communication 2018).

The early relationships between Indigenous peoples and the settlers is described by McGregor (1999) in his book “Wiigwaaskingaa.” Fur trade in the interior areas covered in south-central Ontario resulted from the competition between the French and English fur trading companies. McGregor (1999) indicated that by the early 1500s, beaver pelts had become a precious commodity for the fur trade in the St. Lawrence area and eastward. Overharvesting of beaver left the region depleted. The Wendat (Huron) seized the opportunity to bring beaver pelts from the interior to the trading companies. Samuel de Champlain was among the first French explorers to establish alliances with the Huron and Odawa and to use the trading routes established by Indigenous people. English fur traders soon entered into the pursuit over the monopoly of the fur trade, establishing alliances with the Iroquois which resulted in war between the Iroquois and the Wendat. By the 1780s, the rivalry between the English and the French fur trading companies continued to pit nation against nation for the control of the interior.

According to the history provided by McGregor (1999), one of the first sites of the the Wiigwasskingaa community was at LaCloche Island, named the Bell Rocks (Sinmedweek) because when certain rocks were struck they would ring like a bell. According to oral tradition, these rocks were used as an early warning device to warn of impending attack from nations from the south. Oral tradition indicates that this village was abandoned as they (the villagers) suffered a great tragedy and the dead were buried and the survivors moved away to “Wiigwaaskingaa M’Nising” (Wardrope Island).

By the 1830s, the fur trade was on the wane and was replaced by the timber industry. The villagers began to cut trees for the lumber company. This significantly changed the landscape. At one time, the island was covered with huge birch trees and as time progressed there were fewer trees on the north end of the island.

The signing of the Robinson-Huron Treaty once again promoted a move for the people of Wiigwasskingaa. The villagers were moved to a tract of land (reserve) between two rivers – Whitefish River and Wanabitaseke. In 1906, the community was moved one final time to its present location.

As stated in the previous chapter, according to Nabigon (2006), waabanong (the east) represents new beginnings, new life, vision, birth, food and spring. The teachings associated with this direction are also about feelings. On the positive side of the medicine wheel are good feelings and on the negative side of the medicine wheel, the teachings are related to feeling inferior. The teachings from this direction help us to know and understand each other.

Whether someone comes from the perspective of an Indigenous or non-Indigenous person, it is important to understand the impacts of colonial history. For the Indigenous person, learning about colonial history creates feelings of hurt, anger and possibly shame. For the non-Indigenous person, learning about this history can lead to feelings of remorse and guilt. Some people, whether Indigenous or not, might say that ‘this was a thing of the past’ and prefer to forget about this colonial history.

The Calls to Action from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission recommend that Canadians move towards reconciliation of this colonial history. This involves learning about this colonial history, the true history, not the history that has been presented in history books. It is about ‘re-righting’ the history from an Indigenous perspective. It is about creating a new beginning in Indigenous/non-Indigenous relations and ‘re-storying’ that colonial history as a step towards reconciliation.

This chapter will look at colonial history including the treaty making era, more specifically the Robinson-Huron Treaty area, the area in which Atikameksheng Anishnawbek and Whitefish River First Nation are situated. We will also examine the impacts of the Indian Act, the residential schools and the child welfare system on Indigenous peoples.

When you have worked through the material in this chapter, you will be able to do the following:

Indigenous peoples had organized themselves in federations and confederations through the development of treaties with one another long before the arrival of the Europeans. Treaties were considered sacred and given the highest respect; failure to honour them would result in economic difficulties, political instability, and war (Borrows, 1996). The creation of treaties was not a new concept for Indigenous peoples.

The earliest forms of treaties that have occurred between the settlers and Indigenous peoples in Canada took the form of diplomatic relationships in establishing economic and military alliances. Since that time, treaty making has evolved from creation of alliances to peace and friendship treaties, to land transfer agreements, and finally to the comprehensive land claim agreements that currently take place between the Crown and Indigenous peoples. The wide-ranging, long-standing impacts of these treaties are still affecting the relationships between Canada and Indigenous peoples today.

The Two-Row Wampum Belt (Guswentah) has become known as one of the earliest peace and friendship treaties. The terms of this treaty, made with the Dutch in 1613, signify agreement to live in peace and an understanding that neither would interfere with the internal government of the other. Another peace and friendship treaty was negotiated between the Mi’kmaq and Maliseet peoples of the east coast. Under this treaty, the Mi’kmaq and Maliseet were assured that their religious practices would be undisturbed in return for the promise of peaceful relations. There have been three major treaty making eras since the 16th century, each marked by a specific type of treaty and each having a significant impact on the relationship between Indigenous peoples and the government of Canada. The first form of treaties that were negotiated between Indigenous peoples and the federal government were the Peace and Friendship treaties (1725-1752). These first treaties were negotiated between European nations and First Nations people in order to establish peace and cooperation. There were no land cessions until the 1752 and 1760-61 treaties were signed where a specific trade clause was included. The purpose of these treaties were to re-establish normal relations between the parties after military conflicts.

The second major form of treaties were the Land Transfer treaties. This era began with the Proclamation of 1763, which opened the way to enter into negotiations focused on land transfers. Initially the land transfer treaties were negotiated with the intent of peaceful establishment of an agricultural colony as well as to compensate the allies of First Nations for their losses incurred during the war with the Americans. Later, the nature of the land transfer treaties changed in response to an expanding settler population and the need for more farming land, as well as natural resources such as forestry and mining. Land transfer treaties in Ontario were enacted between 1764-1930 with the intent of encouraging more farming and mining.

The third period of treaty making began in 1973 with the Calder Case, a Supreme Court decision which affirmed Indigenous land rights. This lead to the development of land claims agreements. The purpose of these agreements was to settle outstanding land claims. These agreements also recognize Indigenous rights to self-government.

The interactive timeline below presents some maps that show the various treaty areas of the historical treaties of Canada, pre-1975:

An interactive or media element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here: https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/movementtowardsreconciliation/?p=250

Click on the following link to access the timeline in a new window:

The Seven Years War (1756–63) (the War of Conquest) was a culmination of a century-long battle between France and Britain for domination of North America and world supremacy. The Seven Years War is significant because it is the first global war (Europe, India, and America) fought at both land and sea and it was a crucial turning point in Canadian history.

In North America, the state of war between the French and the British had been going on since 1754. Early in the war, the French (aided by Canadian militia and Indigenous allies) were defeating the British, having captured a number of their forts. On the European front, the Seven Years War pitted the major powers of Britain (allied with Prussia and Hanover) against France (allied with Austria, Sweden, Saxony, Russia, and eventually Spain). Britain concentrated its efforts in Europe but its main aim was to destroy France as a commercial rival, therefore Britain focused its efforts on attacking the French navy and colonies in North America. France, on the other hand, was committed to fighting in Europe (defending Austria), leaving few resources to defend the North American colonies. Huge amounts of money, material and men had been invested in this conflict, leaving both powers exhausted.

In 1758, The British were successful in capturing Louisbourg. They also captured Québec City in 1759 and Montréal in 1760. In 1763, the Treaty of Paris of 1763, formally ceded Canada to the British. Thus, the Seven Years War lay the foundation for biculturalism in Canada.

After the Seven Years War, Britain was the dominant European power in North America, controlling all commercial fur trade but not having full control over the continent. Britain needed to create stable, peaceful relations with First Nations people if they were to remain successful in controlling the colonies. In 1763, King George III issued a Royal Proclamation announcing how the colonies would be administered. Under this proclamation, all lands to the west became the “Indian Territories”; Indian people reserved all unceded territories or land purchased from them, settlement or trade could occur only with the permission of the Indian Department, and only the Crown could purchase land provided there was official sanction from interested Indian people in a public meeting. The Royal Proclamation is significant because it was the first time that Indian rights to lands and title were recognized.

The need by the British government to stabilize the western frontier was fueled by news that an Odawa chief Obwandiyag (also known as Pontiac) was organizing an Indigenous confederacy to demonstrate that Indigenous peoples were still masters of their ancestral lands, despite the British victory over the French army. Pontiac organized an alliance with the Potawatomis and Hurons, convincing them that if they did not stand together, the British would destroy them through malady, small pox or poison. Pontiac’s short lived war of one month sent the British reeling after a series of victories. The British threatened the Indigenous people with smallpox. This resulted in the disintegration of Pontiac’s alliances. Pontiac’s war is significant in that Pontiac foresaw the problems that would impact Indigenous peoples for generations to come.

Up until the late 18th century, commercial and military needs continued to form the basis of the relationship between First Nations people and the Crown. The British government recognized the powerful position of the Indigenous peoples and realized that Indigenous interests needed protection if British commercial interests were to flourish in the interior.

The American War of Independence and the subsequent recognition of the United States of America in 1783 severely impacted the relationship between the British and Indigenous peoples. The loss of the war resulted in approximately 30,000 United Empire Loyalist refugees seeking new land for settlement in the remaining British colonies in North America. In addition, Indigenous people who had fought alongside the British, especially the Six Nations of the Iroquois Confederacy, were also dispossessed by the war. This resulted in the development of a series of land surrender treaties along the St. Lawrence River and down around the Great Lakes, allowing for peaceful establishment of an agricultural colony. At the same time, Indigenous allies were compensated for their losses through the establishment of two reserves for the Six Nations, one at the Bay of Quinte, and the other along the Grand River in an effort to maintain military alliances between the British and Indigenous peoples. This is significant because it strengthened alliances between the British and the Indigenous peoples. When the War of 1812 broke out, Indigenous peoples fought alongside the British to protect against the invasion of the Americans in what is now known as southern Ontario.

Prior to the 1850s, the majority of treaty making in what is now known as Ontario focused exclusively on the Southern Great Lakes and the St. Lawrence River. The need to develop treaties in the Upper Great Lakes was driven by the need for new lands for agricultural settlement and the growing interest from mining companies to explore the lands of the Upper Great Lakes for possible mineral deposits.

Beginning in the 1840s, mining companies sought and acquired licenses from the colonial government to mine in the region even though there were no treaties surrendering the lands. The Anishinaabek of the Upper Great Lakes firmly believed the colony had no rights to the lands. In 1847, to remedy the situation, they petitioned the Governor General for compensation for the lands lost to mining. In 1848, after an investigation into their complaints, the colonial government recommended that treaty negotiations for the lands of the Lakes Superior and Huron watershed take place. In 1849, a violent clash erupted between the First Nations warriors and miners at Batchawana Bay, forcing the colonial officials to move quickly to address the claim and a treaty meeting was scheduled for late summer 1850. The result of this meeting was the signing of the Robinson-Huron Treaty. This treaty covers a large area from the shores of Batchawana Bay on Lake Superior to the shores of Lake Huron, an area that ranges from Sault Ste. Marie eastward and south to Penetanguishene, inclusive of the Sudbury/Manitoulin region of Ontario.

The Robinson Treaty was named after William Benjamin Robinson, a former fur trader from the Muskokas who was tasked with buying up as much land as possible in the upper lakes watershed including the north shore of Lake Huron and the eastern shore of Lake Superior. In the fall of 1850, after an exploratory trip through the proposed surrender lands around Lakes Huron and Superior, Robinson began treaty negotiations with Indigenous communities in the Sault Ste. Marie area. Robinson was prepared to offer a one time payment of £4,000 and a £1,000 per annum thereafter for the territory around the lakes. This offer was refused by the Indigenous leaders of Indigenous nations living around Lake Huron. who had requested a £10 per person annuity and also a large reserve tract. Since Robinson could not persuade the Lake Huron nations to change their position, he negotiated a separate treaty with the Lake Superior nations and then used the Lake Superior treaty as leverage to open negotiations with the Lake Huron nations, indicating that those nations that did not sign would not receive anything.

The differences between the Robinson treaties and preceding ones that were negotiated in Upper Canada is that instead of negotiating for small parcels of land, the Robinson treaties involved the surrender of huge tracts of land with different and disparate groups. In addition, the annuity payments negotiated with the Robinson Treaties changed from yearly lump sum payments to yearly payments in cash going to individual band members. Other terms negotiated were the setting aside of reserve lands for each individual signing group, as well as hunting and fishing rights throughout the treaty territory so long as there was no mining and resource development or settlement. The Robinson treaties were the first treaties to bundle all these elements together effectively, becoming the model upon which subsequent treaties were negotiated.

According to Darrell Boissoneau (ONgov, 2017), president of Shingwauk Kinoomaage Gamig and member of the Bawating (Garden River) community, pre-confederation treaties are treaties that were made before Canada existed. Bawating is the community where the Robinson-Huron Treaty was signed. The pre-confederation treaties are living documents because they were signed in sacred ceremonies. Boissoneau recalls a different version of the development of the Robinson-Huron Treaty making process which is slightly different from the version told from the government perspective. Chief Shingwauk, from Bawating, instigated the treaty. There was some mining development in Mica Bay, in the northern region of Lake Superior, that was happening without the consent of the Anishinaabe people. Chief Shingwauk had petitioned the government to negotiate a treaty but the treaty wasn’t forthcoming quickly enough so he canoed up to Mica Bay with some warriors and scared the miners with a few shots from a cannon. This action pressured the government to enter into treaty negotiations.

Indigenous people were mining well before the arrival of the Europeans. They used various minerals to fabricate tools, weapons, art and other artifacts. There is also evidence that copper trading existed in the Lake Superior area approximately 6000 years ago. As early as 700-1000 BP (Before Present), the Little Passage people (Beothuks) developed chert beds and used the chert (a rock very similar to flint) to make arrowheads and other tools such as scrapers and knives (Pastore, 1998). Indigenous people were also mining silver in the Cobalt area approximately 200 years before arrival of the Europeans.

Greater Sudbury, one of the world’s major mining industries, is known for its large deposits of nickel, copper, palladium, gold and other metals. More recently is the discovery of Chromium. Why is Greater Sudbury so rich in all these metals? Approximately 1.8 billion years ago, a comet collided with the planet forming what is now known as the Sudbury Basin: a crater that is 39 miles long, 19 miles wide and 9.3 miles deep. Greater Sudbury is also known for being one of the locations having the best agricultural land in Northern Ontario due to the high mineral content of the floor of the basin.

Mining occured in the Greater Sudbury area long before the settlers arrived and before the development of the mining industry.There is archeological evidence that the Plano cultures that existed approximately 11,000 years ago used quartzite mined in the Sheguiandah area to fashion tools and weapon heads (Jewiss, 1983). Subsequently, the Northern Shield Cultures used copper and silver to make tools, weapons and jewelry for trade. The minerals that were extracted by these early cultures also provided opportunity for trade relations between other Indigenous cultures thus establishing trade routes throughout Northern Ontario.

According to the Sudbury Mining Journal (1890), mining in Greater Sudbury was discovered accidentally by a young man named McConnell when he got lost while out looking for timber for the Canadian Pacific Railway. The Sudbury Mining Journal contains a wealth of information about mining in Sudbury – the development of the mines; uncertainty about the permanency of mining; the location and range of minerals; the impact of mining laws; the need for a mining act that would encourage people to stay in Canada; the land entitlement process; and a look into a prospectors life.

The following excert from an Interview with Art Petahtegoose from Atikameksheng Anhisnawbek (2018) describes the differences in how Anishinawbek view the land and how the land is viewed by non-Indigenous people. The impact of not understanding the importance of the relationship to the land can have deveasting effects on peoples ability to survive. For example, the gold mine that was operating on Long Lake in the 1900s and again in the 1930s operating on Atikameksheng Anishinabek territory created high levels of arsenic that was leaching into the surrounding waters affecting the recreational area for both the Anishnawbek and non-Indigenous people in the area.

“When we think about what was here before coming into contact with European nations there was a level of thought that was very abstract yet at the same time very sustaining for our population that gave us a way to live on the land, which kept the land green. So we end up living with the lakes and the waters and the land, and what has shifted has a lot to do which he practices in living. So when we look at industry, the hope is that industry will go green. It is going to take some time to get there because technology that we rely on to keep nature green will become better. But if we look at Vale as one example, back in the 1960 time, the hurting years of the Milling operation when they were smelting on the open ground of the ore as it is run through the plant and they are extracting the gold and the nickel and other metals, the toxic gases and run-offs which was emitted through the burning on the rock began to kill the rivers and vegetation. The space where we live and the beings we are have been put into a very narrow niche in surviving, and we have become dependent on that niche but if we start turning that thought upside down we threatened ourselves that kind of understanding is in what is in our way of seeing. Our place in the cosmos is very delicate, so the ultimate question is what do we do? The teachings become important, understanding what that teaching is saying we have got to be able to translate it from our language into forms which can be shared to the modern world. we have to get out of the fear because it is something that our parents did not have, they begin to self doubt. We should not doubt ourselves with the teachings because there is a knowledge there that we need to appreciate.” (Art Petahtegoose, personal communication, 2018)

The relationship between the British and Indigenous peoples changed fundamentally after the War of 1812. Indigenous peoples were no longer needed as military allies. New ideas about this relationship began to take hold. Ideas of British superiority began to emerge fueled by missionaries who believed that Indigenous peoples were ‘savage.’ The role of the government shifted from acknowledging the original peoples of the territories to one where the original peoples were in need of being saved. The government felt that it was their duty to bring Christianity and agriculture to Indigenous peoples. This task became the responsibility of the Indian Department, whose role shifted from solidifying military alliances to encouraging Indigenous peoples to abandon their traditional ways of life in favour of becoming more agricultural and sedentary, just like the British. The Indian Act was created to assimilate Indigenous peoples into mainstream society and contained policies intended to terminate the cultural, social, economic, and political distinctiveness of Indigenous peoples.

To be federally recognized as an Indian either in Canada or the United States, an individual must be able to comply with very distinct standards of government regulation… The Indian Act in Canada, in this respect, is much more than a body of laws that for over a century have controlled every aspect of Indian life. As a regulatory regime, the Indian Act provides ways of understanding Native identity, organizing a conceptual framework that has shaped contemporary Native life in ways that are now so familiar as to almost seem “natural.” (Lawrence, 2003)

The Indian Act originally administered by the Indian Department through Indian Agents has gone through numerous amendments since its creation in 1876. It is now administered by Indian and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC), formerly the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development (DIAND). The Indian Act (1876) is a Canadian federal law that granted the federal government exclusive rights to create legislation regarding Indian status, bands and Indian reserves (Milloy, 2008). In other words, who qualifies to be “Indian.” Under this legislation, the federal government regulated every aspect of life for registered Indians and reserve communities ranging from the imposition of governing structures such as band councils, to control over the rights of Indians to practice their culture and traditions.

Take some time to explore one of the resources identified in the expanding your knowledge section below about the Indigenous perspective on the Indian Act.

Prior to contact, Indigenous peoples had their own rich bodies of knowledge. There was an understanding of the special relationship between knowledge holders/keepers and those seeking knowledge. Knowledge was transmitted from one generation to another through the passing of stories through oral tradition. Indigenous people understood the importance that the next generation played in linking the past and the future. Children were raised with the understanding that they would have a responsibility to carry forward our oral history and our culture to the next generation. Unless you understand the incredible value of the system that existed before the imposition of residential school system, you can never truly understand what was taken from Indigenous peoples.

The residential school system was a powerful force introduced by the church and the government to ‘do away with the Indian Problem.’ The belief was that if you could disconnect the child from their influences (family and community) and instill a different belief system, then they could be absorbed into the ‘body politic.’ In other words, they would become like everyone else.

Sir Hector-Louis Langevin was among the first architects of the residential schools system, which was designed to assimilate Indigenous children into Euro-Canadian culture. In 1883, Langevin presented a proposal to develop three “Indian industrial schools” in the North-West Territories based on the success of these schools in the United States. His model included separation from their parents in order for the schools to be effective:

“The fact is, that if you wish to educate those children you must separate them from their parents during the time they are being educated. If you leave them in the family they may know how to read and write, but they still remain savages, whereas by separating them in the way proposed, they acquire the habits and tastes — it is to be hoped only the good tastes — of civilized people.” (Désilets & Skikavich, 2017, Residential Schools section, para. 2)

An article by CBC news (2017), reports that Indigenous leaders want the name Langevin removed from the block that houses the Prime Minister’s Office, citing that it is named after a strong proponent of the Indian Residential School system. Langevin strongly believed that residential schools were the most expeditious way to assimilate First Nations children into Euro-Canadian society. Indigenous MPs stated that the block should be renamed so that this constant reminder of the devastating effects of the residential schools is removed.

The first residential school in New France (what is now known as Quebec) was established in 1620 by the Recollets – a religious order from France whose ultimate goal was to christianize and civilize (Miller, 1996). Following the Royal Proclamation of 1763, Indigenous leaders such as Peter Jones, John Sunday and Chief Shingwauk envisioned an education system based on partnership and mutual benefit that would place Indigenous people on terms with non-Indigenous people, allowing for meaningful participation in society. However, this view was not supported by all. The government of the day, along with focus on religious instruction and agriculture, proposed an educational system that would assimilate Indigenous people into mainstream society.

The imposition of the Indian Act was the first attempt of the government to assimilate Indigenous people into mainstream society. When this did not happen, the policy shifted to placement of children in residential schools in order to assimilate them into colonial culture. In 1920, an amendment to the Indian Act (1876) made attendance at state-sponsored schools mandatory for all school age children; this was enforced by truant officers. Living conditions in residential schools were horrendous with children living in overcrowded, underfunded facilities resulting in widespread disease and many preventable deaths (Bryce, 1922; Milloy, 1999). In addition, Indigenous children were also subject to widespread sexual abuse (Milloy, 1999; Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, 1996).

Art Petahtegoose (personal communication, 2018) tells a different story of the residential school and the impacts that it had in his community as told to him by his father. In his version of the story, residential schools were put in place because Indigenous people were viewed as a threat to the economy. The Indigenous way of life is not a threat if one understands Anishnawbe teachings and how these teachings provide guidance for living life in a good way. Petahtegoose also talks about reconnecting to Mother Earth as a way of healing from the pain and suffering that resulted from that residential school experience.

Our children being put into the residential schools and the people being subjected to that Indian Act law, the school and that law were designed to erase those knowledge systems, those world views because they were viewed as a threat to the economy. This is in part of what we faced and what we saw and interpreted, it is not a threat and if you take time to study and look closely what is carried within those teachings you begin to see that judgment was made without having gone through those considerations. That’s what we faced in the church, the church that was brought to us, was imposed and our people question what do you think you were doing? There was no consideration and the settlers had said that was just us, and we cannot live like that. My father would always remind the priest or government agent about the way I am living, I am happy with, the way that I have been nurtured, what I understand, is what I know. I know nothing of your government or about your church, what I have seen coming from them has been causing me pain and to recover from that pain I go out into the land and connect with Mother Earth. (Art Petahtegoose, personal communication, 2018)

The following link takes you to a CBC news article about the demands from Indigenous leaders to change the name of Langevin Block, the office of the Prime Minister on Parliament Hill:

Indigenous Leaders Want to Strip Name of Residential School Proponent from Langevin Block

For more information on the residential schools, visit the following link:

Legacy of Hope Foundation

Take some time to view the ‘Where are the children’ video available from the following link, which is a story of the history of residential schools:

Where Are the Children? Healing the Legacy of the Residential Schools (27:49)

A silenced voice is now speaking! The following video shares the stories of Richard Hall & Verna Grozier and their attitudes towards the residential school experience. This video contains some disturbing material about the residential school experience:

Our Stories… Our Strength

The following link provides a timeline about the residential schools in Canada:

100 Years of Loss

“Speaking My Truth” is a compilation of stories as told by survivors of the residential school system. These insights into the residential school experience help one to truly understand the devastating impacts of this system on the lives of Indigenous people. The impacts do not erase with time. Indigenous people live with the experience on a daily basis. It affects their lives and the lives of people around them. These stories are difficult to read and one may feel shame about their ancestor’s role in the experience. However, according to Rogers (2012), to feel no shame would be a real shame. Be prepared for graphic stories and seek help from professionals if the stories impact you on an emotional level.

Speaking my Truth: Reflections on Reconciliation & Residential School

The following is a useful education guide:

Residential Schools in Canada – Education Guide

Indigenous families and communities had their systems for caring for their children based on their cultural practices, laws, and traditions. Children were viewed as gifts from the creator and the parents’ responsibility was to raise the spirit of the child. Extended family were closely involved in the raising of the child. Traditional child rearing practices were disrupted by the imposition of colonial policies such as the Indian Act and the establishment of the residential school system.

According to Milloy (1999), in addition to being a force of assimilation, the residential schools served as mechanisms for state care for neglected and abused Indigenous children. When the residential school system began to phase out during the second half of the 20th century, responsibility for Indigenous child welfare shifted to the child welfare system.

In 1951, the Indian Act was amended to include the “general law of applicability” (Section 88), which meant that provincial or territorial child welfare legislation could now be applied on-reserve. Initially, the provinces and territories could intervene on-reserve only in extreme emergencies. Under this new arrangement, the allocation of federal funds now allowed for the delivery of provincial and territorial support for on-reserve services. The result was a massive and permanent removal of Indigenous children from their homes and communities and placement in foster care and/or adoption. According to the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (1996), over 11,000 Indigenous children were adopted between 1960 and 1990, a period coined the ‘Sixties Scoop.’

In response to the wide scale removal of Indigenous children from their homes and communities, as well as the horrific treatment of Indigenous children by provincial and territorial child welfare authorities, Indigenous groups began to explore the possibility of developing their own on-reserve, federally funded child welfare agencies (Auditor General of Canada, 2008).

In 1979, Northern Ontario Indian Bands began to raise concerns about the increasing numbers of Indigenous children in the care of Children’s Aid Societies. In December 1981, in response to these concerns, the Chiefs of Ontario endorsed the following Resolution:

“That the child welfare agencies of Ontario and Manitoba shall not remove our children from our reserves and shall return to their Bands those of our children whom they have removed in the past; and that we the Indian Nations in Ontario shall create our own Indian Child Welfare laws, policies and programs, based on the protection of the family and the preservation of their Indian culture within the Indian family.” (Dilico Anishinabek Family Care, 2018)

First Nations child and family service agencies have been in existence since the early 1980s. In Northern Ontario, Weechi-it-te-win Family Services was the first Indigenous organization to receive its child welfare mandate in 1983. Anishinaabe Abinoojii Family Services has been providing prevention services since 1986 and was the first mandated children’s aid society on reserve in the province of Ontario in 1991. Dilico Ojibway Child and Family Services received its mandate as a Native Children’s Aid Society in 1995.

In 1995, Kina Gbezghomi Child and Family Services, whose head office was located in Wikwemikong, was in the process of applying for society mandate but this was put on hold because the Ministry of Community, Family and Children’s Services, in collaboration with Indian Northern Affairs Canada, initiated a review of all Native Child Welfare agencies in Ontario. This affected the five Native agencies providing protection services as well as those that had pre-mandate status. As a result of this review process, the Ministry of Community, Family and Children’s Services issued a “moratorium” halting any future designations of Native Child Welfare agencies in Ontario. Major concerns expressed in the final report related to accountability mechanisms around the transfers of funds and delivery of service from the transferring agent to First Nation communities.

The number of Indigenous child welfare agencies has expanded since the government lifted its moratorium on the designation of new agencies. Indigenous child welfare agencies are challenged with complying with Directive 20-1 (a national funding formula directed at Indigenous child welfare agencies), provincial standards and strict controls on funding. Despite this, there is continued growth in the number of Indigenous child welfare agencies and their scope is expanding to include both on- and off-reserve populations as well.

Indigenous communities are recognizing that western mainstream approaches to child welfare are not working with their members as the developmental theories used fail to acknowledge ‘spirit.’ Indigenous approaches to addressing child welfare issues incorporate the worldview, cultural structures, and cultural attachment opportunities into service provision. Indigenous communities are moving towards a strong culturally restorative, bi-cultural practice model that incorporates both worldviews and their subsequent philosophies (Simard & Blight, 2011).

The following link takes you to the Weechi-it-te-win Family Services website. Take a few minutes to explore this website. What is your first impression of this website? How friendly is the website to Indigenous people?

Weechi-it-te-win Family Services

The teachings of Zhawaanong (the south) include: Time, relationships, youth, and patience. The positive side of the medicine wheel talks about creating good relationships. It takes time to build good relationships with people (Nabigon, 2006). The opposite of building good relationships is described as envy. When people are envious, they are said to want to have what others have but are not willing to work for it. Therefore, to build good relationships one must work for it. Indigenous people have worked hard to create spaces where they can use the gifts that have been given to them – traditions, culture, healing practices, governance systems, and ways of being and knowing. Many non-Indigenous people are drawn to the services offered by Indigenous organizations because of their holistic approaches and their ability to provide culturally relevant programs and services.