“Time is the only commodity that matters.”

– Randy Pausch

My favorite aspect of time is its equality. Regardless of our race, religion, or age, all of us have the same amount of time in a day, week, month and year. Wealthy people cannot buy more time and poor people do not receive less time. A minute for a tall person is the same amount of time for a short person. An hour for a woman is the same amount of time for a man. Regardless of how many languages someone speaks, their sexual orientation, ethnicity, educational background, income or experience, we all have 365 days in a year. Some people will live longer than others, but when comparatively measuring how much time humans have with each other, we all have the same amount.

Time is a popular philosophical concept. You may have heard some of the following sayings:

- Time flies when you are having fun

- That is a waste of time

- Time is money

- We have all the time in the world

- That was an untimely death

- The time is right

- I’m having the time of my life

- Time heals all wounds

- We have some time to kill

What do the sayings mean to you?

Time is also how we keep track of when we’re supposed to be and where we’re supposed to be (work, home, class, meeting friends and family, etc.). Think about how many measures of time you have in your home (clocks, watches, cell phones, TVs, DVRs, computers, microwaves, ovens, thermostats, etc.). It is obvious time is important to us.

Time: A Limited and Precious Commodity

We cannot go back in time. If I used my time poorly last Wednesday, I can do nothing to get it back. Other commodities may allow for accumulating more or starting over, but time does not. We cannot “save” time nor earn more time.

“If you had a bank that credited your account each morning with $86,400, but carried no balance from day to day and allowed you to keep no cash in your account, and every evening cancelled whatever part of the amount you had failed to use during the day, what would you do? Draw out every cent, of course! Well, you have such a bank, and its name is time. Every morning it credits you with 86,400 seconds. Every night it writes off as lost whatever of these you have failed to invest to good purpose. It carries no balance; it allows no overdrafts. Each day it opens a new account with you. Each night it burns the record of the day. If you fail to use the day’s deposit, the loss is yours. There is no going back. There is no drawing against the morrow. You must live in the present – on today’s deposit. Invest it so as to get the utmost in health and happiness and success.”

– Anonymous

Technically, time cannot be managed, but we label it time management when we talk about how people use their time. We often bring up efficiency and effectiveness when discussing how people spend their time, but we cannot literally manage time because time cannot be managed. What we can do though, is find better ways to spend our time, allowing us to accomplish our most important tasks and spend time with the people most important to us.

Human babies do not come with instruction manuals. There is nothing to follow to know how we are supposed to spend our time. Most of us spend our time doing a combination of what interests us, what is important to us and what we feel we “have” to do.

What is your relationship with time? Are you usually early, right on time or late? Do you find yourself often saying, “I wish I had more time?” Are you satisfied with your relationship with time or would you like to change it?

The Value of Time

It is also important to determine how much your time is worth to you. If someone were to negotiate for an hour of your time, how much would that be worth to you? We often equate time with money. Many of us work in positions where we are paid by the hour; this gives us some gauge of what we are worth to our employers. Some items we purchase because we think they are of good value for their price. Others we pass on. Are some hours of your day more important or more valuable than others? Why? Are you more productive in the morning or in the evening? Once people realize how valuable time is, they often go to great lengths to protect it because they understand its importance. How much would you pay for an additional hour in a day? What would you do with that time? Why?

What is the value of your time? How much is an hour of your time worth? If someone were to pay you $10 to do a job, how much time would that be worth? $20? $50?

How Do I Allocate My Time?

“Lack of direction, not lack of time is the problem. We all have 24 hour days.”

– Zig Ziglar

Most of us know there are 24 hours in a day, but when I ask students how many hours are in a week, many do not know the answer. There are 168 hours in a week (24 hours multiplied by seven days). I don’t believe that it is imperative that students know how many hours are in a week, but it helps when we start to look at how much time we have in a week, how we want to spend our time and how we actually spend our time.

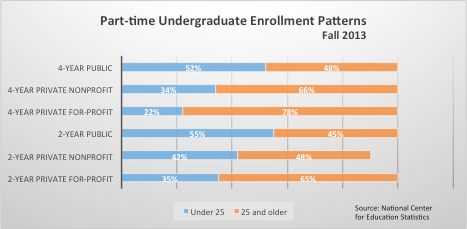

One challenge for many students is the transition from the structure of high school to the structure of college. In high school, students spend a large portion of their time in class (approximately 30 hours in class per week), while full-time college students may spend only one-third of that time in class (approximately 12 hours in class per week). Further, college students are assigned much more homework than high school students. Think about how many times one of your high school teachers gave you something to read during class. In college, students are given more material to read with the expectation that it is done outside of class.

This can create challenges for students who are unable to set aside proper study time for each of their courses. Keep in mind for full-time students: your college educational day should not be shorter than your high school day.

Hourly Recommendations (per Week)

Work | Units | Study Time | Total |

40 | 6 | 12 | 58 |

30 | 9 | 18 | 57 |

20 | 12 | 24 | 56 |

I use this table frequently in counseling appointments, classes and orientations. It’s a guide for students that provides an idea of how much time students spend with work and school, and what experts recommend for a specific amount of work hours that correlates with a specific number of units. I like to ask students how they spend their week. Students always know their work hours and their class times. These are easy to place in a schedule or on a calendar because they are predetermined. But study time is the one area that consistently is left out of a student’s schedule. It takes initiative to include it in a student’s busy week and self-discipline to stick to it. Here’s a tip: Write your study time into your schedule or calendar. It’s important to do this because it’s easy to skip a study session or say to yourself, “I’ll do it later.” While there would likely be an immediate consequence if you do not show up for work, there is not one if you fail to study on Tuesday from 3pm-4pm. That consequence may take place later, if the studying is not made up.

It is widely suggested that students need to study approximately two hours for every hour that they spend in class in order to be successful. Thus, if I am taking a class that meets on Mondays and Wednesdays from 4pm-5:30pm (three hours per week), I would want to study outside of class six hours per week. This is designed as a guide and is not an exact science. You might need to spend more time than what is recommended if you are taking a subject you find challenging, have fallen behind in or if you are taking short-term classes. This would certainly be true if I were to take a physics class. Since I find learning physics difficult, I might have to spend three or four hours of study time for each hour of class instruction. You also might need to study more than what is recommended if you are looking to achieve better grades. Conversely, you might need to spend less time if the subject comes easy to you (such as sociology does for me) or if there is not a lot of assigned homework.

Keep in mind that 20 hours of work per week is the maximum recommended for full-time students taking 12 semester units in a term. For students working full-time (40 hours a week), no more than six units is recommended. The total is also a very important category. Students often start to see difficulty when their total number of hours between work and school exceeds 60 per week. The amount of sleep decreases, stress increases, grades suffer, job performance decreases and students are often unhappy.

How do you spend your 168 hours in a week?

- Child Care

- Class

- Community Service / Volunteer

- Commuting / Transportation

- Eating / Food Preparation

- Exercise

- Family

- Friends

- Household / Child Care Duties

- Internet / Social Media / Phone / Texting

- Party

- Recreation / Leisure

- Relationship

- Sleeping

- Spirituality / Prayer / Meditation

- Study

- Video Games

- Watching TV or Movies, Netflix, Youtube

- Work / Career

There is also the time it takes for college students to adjust to college culture, college terminology, and college policies. Students may need to learn or relearn how to learn and some students may need to learn what they need to know. What a student in their first college semester needs to know may be different than what a student in their last college semester needs to know. First semester students may be learning where classrooms are, building hours and locations for college resources, and expectations of college students. Students in their last semester may be learning about applying for their degree, how to confirm they have all of their requirements completed for their goal, and commencement information. Whatever it is students may need to learn, it takes time.

Fixed Time vs. Free Time

Sometimes it helps to take a look at your time and divide it into two areas: fixed time and free time. Fixed time is time that you have committed to a certain area. It might be school, work, religion, recreation or family. There is no right or wrong to fixed time and everyone’s is different. Some people will naturally have more fixed time than others. Free time is just that—it is free. It can be used however you want to use it; it’s time you have available for activities you enjoy. Someone might work 9am-2pm, then have class 3pm-4:30pm, then have dinner with family 5pm-6pm, study 6pm-7pm and then have free time from 7pm-9pm. Take a look at a typical week for yourself. How much fixed time do you have? How much free time? How much fixed and free time would you like to have?

Identifying, Organizing and Prioritizing Goals

The universal challenge of time is that there are more things that we want to do and not enough time to do them.

I talk to students frequently who have aspirations, dreams, goals and things they want to accomplish. Similarly, I ask students to list their interests at the beginning of each of my classes and there is never a shortage of items. But I often talk to students who are discouraged by the length of time it is taking them to complete a goal (completing their education, reaching their career goal, buying a home, getting married, etc.). And every semester there are students that drop classes because they have taken on too much or they are unable to keep up with their class work because they have other commitments and interests. There is nothing wrong with other commitments or interests. On the contrary, they may bring joy and fulfillment, but do they get in the way of your educational goal(s)? For instance, if you were to drop a class because you required surgery, needed to take care of a sick family member or your boss increased your work hours, those may be important and valid reasons to do so. If you were to drop a class because you wanted to binge watch Grey’s Anatomy, play more Minecraft, or spend more time on Facebook, Twitter, or Instagram, you may have more difficulty justifying that decision, but it is still your decision to make. Sometimes students do not realize the power they have over the decisions they make and how those decisions can affect their ability to accomplish the goals they set for themselves.

I am no exception. I have a long list of things that I want to accomplish today, tomorrow, next week, next month, next year and in my lifetime. I have many more things on my list to complete than the time that I will be alive.

Identifying Goals

Recently, there has been a lot of attention given to the importance of college students identifying their educational objective and their major as soon as possible. Some high schools are working with students to identify these goals earlier. If you are interested in career identification, you may wish to look into a career decision making course offered by your college. You may also wish to make an appointment with a counselor, and/or visit your college’s Career Center and/or find a career advice book such as What Color is Your Parachute? by Richard N. Bolles.

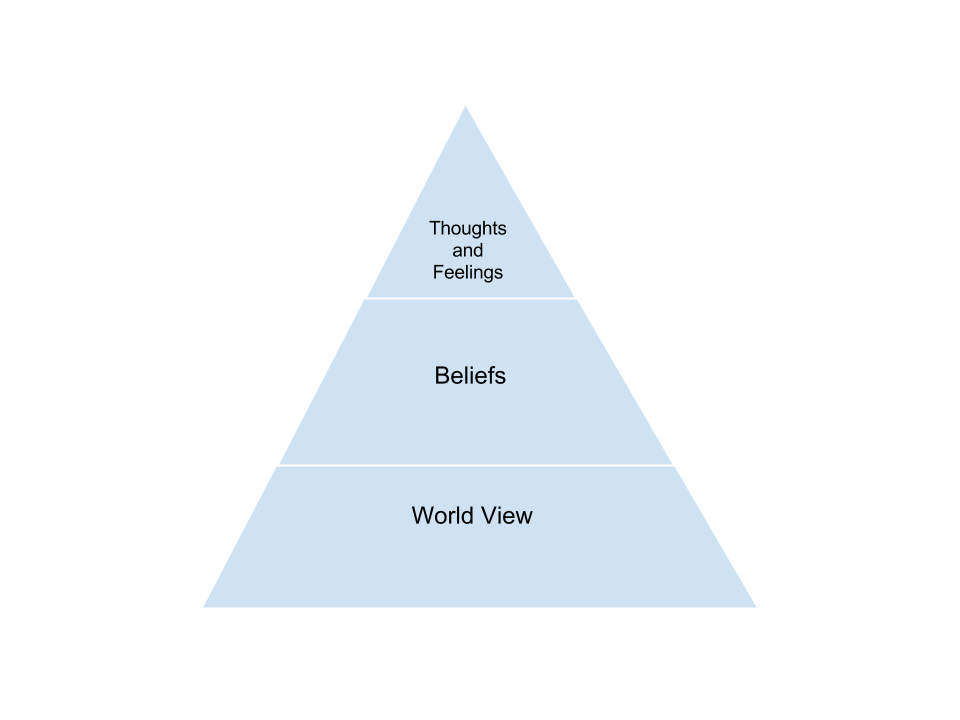

Goal identification is a way to allow us to keep track of what we would like to accomplish as well as a mechanism to measure how successful we are at achieving our goals. This video gives modern practical advice about the future career market.

Video: Success in the New Economy, Kevin Fleming and Brian Y. Marsh, Citrus College:

A Vimeo element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here: https://press.rebus.community/blueprint2/?p=292

Educational Planning

There has also been focused attention on the importance of educational planning.

Education plans developed with a counselor help students determine and explore a program of study and have proven to facilitate student success.

Students can follow educational plans like a road map so they can see how to complete required classes in the most efficient and logical order based on their educational goals.

Educational planning may appear to be simple: identifying the program of study and then figuring out which courses are required to complete it.

Graphics courtesy of Greg Stoup, Rob Johnstone, and Priyadarshini Chaplot of The RP Group

However, it can often be extremely complex. Many students have multiple goals. One student might be interested in more than one of these goals: earn multiple degrees, transfer to a four-year college or university, prepare for graduate school, start a minor, or complete requirements for several transfer schools.

Students also have different strengths. Some might be strong in English. Some students excel in Math. Others might be strong in Science, Arts and Humanities, or Social Sciences. Educational planning takes these strengths (and weaknesses) into consideration. Students are encouraged to take English and Math early, as statistics show that those students will be more successful. But the order of courses taken for students with different strengths could vary even if the students have the same goal. There is not a one-size-fits-all solution.

Educational planning may be further complicated by availability of courses a college or university offers, the process in which a student may be able to register for those courses and which sections fit into students’ schedules. Transcript evaluations (if students have attended previous colleges or universities), assessment of appropriate English or Math levels and prerequisite clearance procedures may also contribute to the challenge of efficient educational planning.

Further, students have different priorities. Some students want to complete their goals in a certain amount of time. Other students may have to work full-time and take fewer units each semester. Educational planning might also consider student interests, skills, values, personality, or student support referrals. Grade point average requirements for a student’s degree, transfer or specific programs are also considered in educational planning.

While some students may know what they want to do for their career, and have known since they were five years old, many students are unsure of what they want to do. Often, students aren’t sure how to choose their major. A major is an area of concentration in which students will specialize at a college or university. Completing a major requires passing courses in the chosen concentration and degrees are awarded that correlate with students’ majors. For instance, my bachelor’s degree in Sociology means that my major was Sociology.

It is OK to not know what major you want to pursue when you start college, but I suggest careful research to look into options and narrow them down to a short list of two or three. Talking with a counselor, visiting your college’s Career Center, or taking a college success class may help with your decisions.

Seventy percent of students change their major at least once while in college and most will change their major at least three times. It is important for students to find the best major for them, but these changes may make previous educational plans obsolete.

The simple concept and road map often ends up looking more like this:

Graphics courtesy of Greg Stoup, Rob Johnstone, and Priyadarshini Chaplot of The RP Group

Due to the complicated nature of educational planning, a counselor can provide great value for students with assistance in creating an educational plan, specifically for each individual student. If you have not done so already, I highly recommend you meet with a counselor and continue to do so on a frequent basis (once per semester if possible).

How To Start Reaching Your Goals

Without goals, we aren’t sure what we are trying to accomplish, and there is little way of knowing if we are accomplishing anything. If you already have a goal-setting plan that works well for you, keep it. If you don’t have goals, or have difficulty working towards them, I encourage you to try this.

Make a list of all the things you want to accomplish for the next day. Here is a sample to do list:

- Go to grocery store

- Go to class

- Pay bills

- Exercise

- Social media

- Study

- Eat lunch with friend

- Work

- Watch TV

- Text friends

Your list may be similar to this one or it may be completely different. It is yours, so you can make it however you want. Do not be concerned about the length of your list or the number of items on it.

“Obstacles are things a person sees when he takes his eyes off his goal.”

– E. Joseph Cossman

You now have the framework for what you want to accomplish the next day. Hang on to that list. We will use it again.

Now take a look at the upcoming week, the next month and the next year. Make a list of what you would like to accomplish in each of those time frames. If you want to go jet skiing, travel to Europe or get a bachelor’s degree: Write it down. Pay attention to detail. The more detail within your goals the better. Ask yourself: what is necessary to complete your goals?

With those lists completed, take into consideration how the best goals are created. Commonly called “SMART” goals, it is often helpful to apply criteria to your goals. SMART is an acronym for Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Realistic and Timely. Perform a web search on the Internet to find out more about “SMART” goals. Are your goals SMART goals? For example, a general goal would be, “Achieve an ‘A’ in my anatomy class.” But a specific goal would say, “I will schedule and study for one hour each day at the library from 2pm-3pm for my anatomy class in order to achieve an ‘A’ and help me gain admission to nursing school.”

Now revise your lists for the things you want to accomplish in the next week, month and year by applying the SMART goal techniques. The best goals are usually created over time and through the process of more than one attempt, so spend some time completing this. Do not expect to have “perfect” goals on your first attempt. Also, keep in mind that your goals do not have to be set in stone. They can change. And since over time things will change around you, your goals should also change.

Another important aspect of goal setting is accountability. Someone could have great intentions and set up SMART goals for all of the things they want to accomplish. But if they don’t work towards those goals and complete them, they likely won’t be successful. It is easy to see if we are accountable in short-term goals. Take the daily to-do list for example. How many of the things that you set out to accomplish, did you accomplish? How many were the most important things on that list? Were you satisfied? Were you successful? Did you learn anything for future planning or time management? Would you do anything differently? The answers to these questions help determine accountability.

Long-term goals are more difficult to create and it is more challenging for us to stay accountable. Think of New Year’s Resolutions. Gyms are packed and mass dieting begins in January. By March, many gyms are empty and diets have failed. Why? Because it is easier to crash diet and exercise regularly for short periods of time than it is to make long-term lifestyle and habitual changes.

Randy Pausch was known for his lecture called “The Last Lecture,” now a bestselling book. Diagnosed with terminal pancreatic cancer, Pausch passes along some of his ideas for best strategies for uses of time in his lesser known lecture on time management. I don’t believe there is someone better suited to teach about time management than someone trying to maximize their last year, months, weeks and days of their life.

Video: Time Management, Randy Pausch.

A YouTube element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here: https://press.rebus.community/blueprint2/?p=292

Organizing Goals

Place all of your goals, plans, projects and ideas in one place. Why? It prevents confusion. We often have more than one thing going on at a time and it may be easy to become distracted and lose sight of one or more of our goals if we cannot easily access them. Create a goal notebook, goal poster, goal computer file—organize it any way you want—just make sure it is organized and that your goals stay in one place.

Author’s Story

I learned this lesson the hard way. Some years ago, I used sticky notes all the time. I think they are a great invention and believe they help me stay organized. But one day when I was looking for a phone number I realized that I had sticky notes at work, sticky notes at home and sticky notes in my car. I had so many sticky notes in multiple places that I couldn’t easily find the information I needed. Everyone has a preference of how clean or messy his or her work area is, but if you’re spending time looking for things, it is not the best use of your time. I now keep all of my sticky notes in one place. Further, I always use one and only one point of entry for anything that goes on my calendar. I have also found many advances in technology to assist with organization of information. But I still use physical sticky notes.

Use Technology to your Advantage

Software and apps are now available to help with organization and productivity. Check out Evernote, One Note, or Stickies.

Break Goals into Small Steps

I ask this question of students in my classes: If we decided today that our goal was to run a marathon and then went out tomorrow and tried to run one, what would happen? Students respond with: (jokingly) “I would die,” or “I couldn’t do it.” How come? Because we might need training, running shoes, support, knowledge, experience and confidence—often this cannot be done overnight. But instead of giving up and thinking it’s impossible because the task is too big for which to prepare, it’s important to develop smaller steps or tasks that can be started and worked on immediately. Once all of the small steps are completed, you’ll be on your way to accomplishing your big goals.

What steps would you need to complete the following big goals?

- Buying a house

- Getting married

- Attaining a bachelor’s degree

- Destroying the Death Star

- Losing weight

Prioritizing Goals

Why is it important to prioritize? Let’s look back at the sample list. If I spent all my time completing the first seven things on the list, but the last three were the most important, then I would not have prioritized very well.

It would have been better to prioritize the list after creating it and then work on the items that are most important first. You might be surprised at how many students fail to prioritize.

After prioritizing, the sample list now looks like this:

- Go to class

- Work

- Study

- Pay bills

- Exercise

- Eat lunch with friend

- Go to grocery store

- Text friends

- Social media

- Watch TV

One way to prioritize is to give each task a value. A = Task related to goals; B = Important—Have to do; C = Could postpone. Then, map out your day so that with the time available to you, work on your A goals first. You’ll now see below our list has the ABC labels. You will also notice a few items have changed positions based on their label. Keep in mind that different people will label things different ways because we all have different goals and different things that are important to us. There is no right or wrong here, but it is paramount to know what is important to you, and to know how you will spend the majority of your time with the things that are the most important to you.

A Go to class

A Study

A Exercise

B Work

B Pay bills

B Go to grocery store

C Eat lunch with friend

C Text friends

C Social media

C Watch TV

Do the Most Important Things First

You do not have to be a scientist to realize that spending your time on “C” tasks instead of “A” tasks won’t allow you to complete your goals. The easiest things to do and the ones that take the least amount of time are often what people do first. Checking Facebook or texting might only take a few minutes but doing it prior to studying means we’re spending time with a “C” activity before an “A” activity.

People like to check things off that they have done. It feels good. But don’t confuse productivity with accomplishment of tasks that aren’t important. You could have a long list of things that you completed, but if they aren’t important to you, it probably wasn’t the best use of your time.

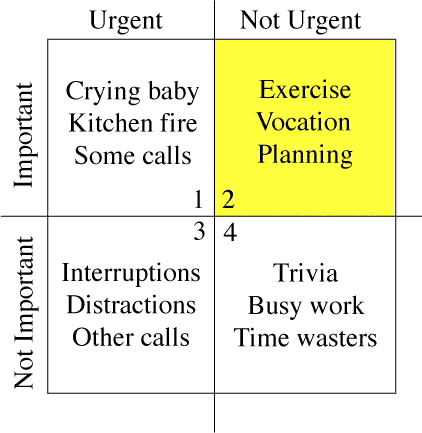

Perform an internet search for “Time Management Matrix images.” The matrix (also referred to in the Randy Pausch video), shows how to categorize your tasks and will help prioritize your goals, tasks, and assignments. Take a look at the matrix and quadrants and identify which quadrant your activities would fall into.

Quadrant I (The quadrant of necessity): Important and Urgent

Only crisis activities should be here. If you have included exams and papers here, you are probably not allowing yourself enough time to fully prepare. If you continue at this pace you could burn out!

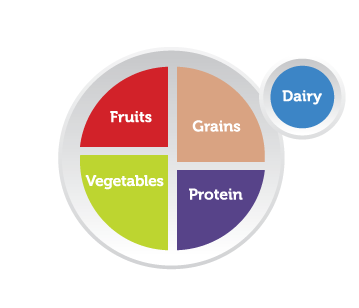

Quadrant II (The quadrant of quality and personal leadership): Important and Not Urgent

This is where you define your priorities. What’s important in your life? What will keep you balanced? For example, you may know that good nutrition, sleep, recreation and maintaining healthy social relationships are important but do you consciously make time for them in your daily or weekly routine? Quadrant II includes your “A” goals. Managing your life and the lifestyle will help you manage your time.

Quadrant III (The quadrant of deception): Not Important and Urgent

While you may feel that activities, such as texting, need your attention right away, too much time spent on Quadrant III activities can seriously reduce valuable study time. This may leave you feeling pulled in too many directions at once.

Quadrant IV (The quadrant of waste): Not Important and Not Urgent

Quadrants three and four include your “C” goals. If you’re spending many hours on Quadrant IV activities, you’re either having a great deal of fun or spending a lot of time procrastinating! Remember, the objective is balance. You may notice I placed social media and texting into this category. You could make a case that social media, texting, Netflix, and Youtube are important, but how often are they urgent? Ultimately, it is up to you to decide what is important and urgent for yourself, but for the context of this textbook, your classes, assignments, preparation, and studying should almost universally be more urgent and important than social media and texting.

Here is an adapted version of the matrix, with an emphasis on quadrant II.

Conclusion

Managing time well comes down to two things. One is identifying (and then prioritizing) goals and the other is having the discipline to be able to work towards accomplishing them. We all have the same amount of time in a day, week, month and year, yet some people are able to accomplish more than others. Why is this? Often, it is because they are able to set goals, prioritize them and then work on them relentlessly and effectively until they are complete.