Professional Communications: Foundations

Professional Communications: Foundations by Olds College is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Professional Communications: Foundations by Olds College is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

1

I thought it easier to include all the info here. This way, you just need to log in to Pressbooks to get all the info you need for our collaboration on Wendy Ward’s open textbook adoption.

Thank you again for lending your support; I hope you find Pressbooks easy to use and might even see use for it in your own Library. Just a couple of background things on Pressbooks:

For a consistent table of contents (TOC) and easier student navigation, many sections across chapters are the same. By using H1 in formatting, these headings will appear in the TOC. For instance: Learning Outcomes, Key Takeaways & Check In, and References are all H1. Longer chapters, with multiple concepts also use H1 to help chunk up the content.

And since I mentioned chapters, it’s likely time to discuss a quirkiness of Pressbooks. What we think of as chapters are actually Parts in Pressbooks. For our purposes, each module is a Part and each Chapter is a chapter as per the original resource e.g., http://www.procomoer.org/writing/.

I removed the Topics section of each chapter; it seemed a tad cluttered as up front information and was often redundant to the learning objectives.

That’s enough for now! We will go through everything in person where it will make much more sense.

Take care,

Peggy

An interactive or media element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/foundationsprofcomms/?p=1205

2

I

1

The chapters in this module include:

The focus of this module is on establishing important foundational skills to address the complexities of communicating in the modern-day professional environment. Although work contexts and technology are continually changing, the key principles of communication remain the same and as relevant as ever.

By completing this module, you should understand how audience characteristics and choice of words and | or images affect the crafting of meaningful messages. You should learn how to choose an appropriate delivery method for your message and how to use feedback to measure and improve its success. This module will stress key principles of professional communication.

You can apply the knowledge and skills developed in this module to a variety of communication contexts.

Communication is key to your success—in relationships, at work, as a citizen of your country, and throughout your lifetime. Your ability to communicate comes from experience, and experience can be an effective teacher. This module, and the related communication course it is part of, will provide you with some experiences to help you communicate effectively in a professional context where change is rapid and you are expected to keep up. Whether you are (re-)entering the workforce or feel the need to brush up on your communication skills, this module should help you understand professional communication fundamentals that you can apply to your own context.

You did not learn to text in a day and did not learn all the shorthand—from LOL (laugh out loud) to BRB (be right back)—right away. In the same way, learning to communicate well requires you to observe and get to know how others have expressed themselves, then adapt what you have learned to your current task—whether it’s texting a brief message to a friend, presenting your qualifications in a job interview, or writing a business report.

Effective communication takes preparation, practice, and persistence. There are many ways to learn communication skills. The school of “hard knocks” is one of them. But in the business environment, a “knock” (or lesson learned) may come at the expense of your credibility through a blown presentation to a client.

This module contains a compilation of information and resources, such as readings, articles, activities, videos, and infographics, offering you a trial run that allows you to try out new ideas and skills before you have to use them in “real life.” Listening to yourself or perhaps the comments of others may help you reflect on new ways to present or perceive thoughts, ideas, and concepts. The net result is your growth; ultimately, your ability to communicate in business will improve, opening more doors than you might anticipate.

Chapters within module centre on overarching learning goals. Goals are further described in terms of (a) specific knowledge, skills, and attitudes required to achieve the goals, and (b) specific learning outcomes that serve as evidence of achieving learning goals. The learning goals in this module are at an introductory level and are relevant to introductory communication tasks.

The learning goals for this module are that upon completing the readings and activities presented in this module, you should be able to do the following:

Upon successfully completing this module, you should:

Understand the following:

Know the following:

Be able to do the following:

Upon successfully completing this module, you should be able to:

2

Upon completing this chapter | module, you should be able to:

Think about communication in your daily life. When you make a phone call, send a text message, or like a post on Facebook, what is the purpose of that activity? Have you ever felt confused by what someone is telling you or argued over a misunderstood email? The underlying issue may very well be a communication deficiency.

There are many current models and theories that explain, plan, and predict communication processes and their successes or failures. In the workplace, we might be more concerned about practical knowledge and skills than theory. However, good practice is built on a solid foundation of understanding and skill. For this reason this module will help you develop foundational skills in key areas of communication, with a focus on applying theory and providing opportunities for practice.

The word communication is derived from a Latin word meaning “to share.” Communication can be defined as “purposefully and actively exchanging information between two or more people to convey or receive the intended meanings through a shared system of signs and (symbols)” (“Communication,” 2015, para. 1).

Let us break this definition down by way of example. Imagine you are in a coffee shop with a friend, and they are telling you a story about the first goal they scored in hockey as a child. What images come to mind as you hear their story? Is your friend using words you understand to describe the situation? Are they speaking in long, complicated sentences or short, descriptive sentences? Are they leaning back in their chair and speaking calmly, or can you tell they are excited? Are they using words to describe the events leading up to their big goal, or did they draw a diagram of the rink and positions of the players on a napkin? Did your friend pause and wait for you to to comment throughout their story or just blast right through? Did you have trouble hearing your friend at any point in the story because other people were talking or because the milk steamer in the coffee shop was whistling?

All of these questions directly relate to the considerations for communication in this module:

Before we examine each of these considerations in more detail, we should consider the elements of the communication process.

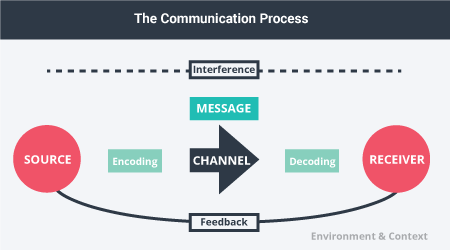

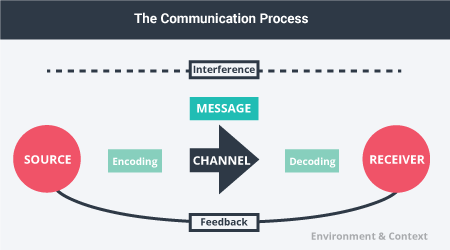

The Communication Process by L. Underwood

The communication process includes the steps we take in order to ensure we have succeeded in communicating. The communication process comprises essential and interconnected elements detailed in the figure above. We will continue to reflect on the story of your friend in the coffee shop to explore each element in detail.

Source: The source comes up with an idea and sends a message in order to share information with others. The source could be one other person or a group of people. In our example above, your friend is trying to share the events leading up to their first hockey goal and, likely, the feelings they had at the time as well.

Message: The message is the information or subject matter the source is intending to share. The information may be an opinion, feelings, instructions, requests, or suggestions. In our example above, your friend identified information worth sharing, maybe the size of one of the defence players on the other team, in order to help you visualize the situation.

Channels: The source may encode information in the form of words, images, sounds, body language, etc. There are many definitions and categories of communication channels to describe their role in the communication process. This module identifies the following channels: verbal, non-verbal, written, and digital. In our example above, your friends might make sounds or use body language in addition to their words to emphasize specific bits of information. For example, when describing a large defence player on the other team, they may extend their arms to explain the height or girth of the other team’s defence player.

Receiver: The receiver is the person for whom the message is intended. This person is charged with decoding the message in an attempt to understand the intentions of the source. In our example above, you as the receiver may understand the overall concept of your friend scoring a goal in hockey and can envision the techniques your friend used. However, there may also be some information you do not understand—such as a certain term—or perhaps your friend describes some events in a confusing order. One thing the receiver might try is to provide some kind of feedback to communicate back to the source that the communication did not achieve full understanding and that the source should try again.

Environment: The environment is the physical and psychological space in which the communication is happening (Mclean, 2005). It might also describe if the space is formal or informal. In our example above, it is the coffee shop you and your friend are visiting in.

Context: The context is the setting, scene, and psychological and psychosocial expectations of the source and the receiver(s) (McLean, 2005). This is strongly linked to expectations of those who are sending the message and those who are receiving the message. In our example above, you might expect natural pauses in your friend’s storytelling that will allow you to confirm your understanding or ask a question.

Interference: There are many kinds of interference (also called “noise”) that inhibit effective communication. Interference may include poor audio quality or too much sound, poor image quality, too much or too little light, attention, etc. In our working example, the coffee shop might be quite busy and thus very loud. You would have trouble hearing your friend clearly, which in turn might cause you to miss a critical word or phrase important to the story.

Those involved in the communication process move fluidly between each of these eight elements until the process ends.

Now that we have defined communication and described a communication process, let’s consider communication skills that are foundational to communicating effectively.

An interactive or media element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/foundationsprofcomms/?p=1021

An interactive or media element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/foundationsprofcomms/?p=1021

McLean, S. (2005). The basics of interpersonal communication. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Communication. (n.d.). In Wikipedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Communication.

3

Upon completing this chapter, you should be able to:

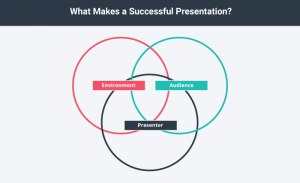

The communications landscape changes rapidly over time, but one criterion for successful communication remains the same: the importance of knowing who your audience is and understanding their needs. Imagine you want to give a presentation to people in your department at work. You likely know your colleagues’ personalities and what they expect of you. You might know their education levels and you are sure they understand all of your company-specific jargon. You think delivering your message should be easy, except many of them are so comfortable with you, they decide to skip your presentation because you took for granted that they would be interested. On the other hand, if you had to present to the board of directors, you might need to do more homework on who they are and what they expect from you. In other words, it is always important to get to know your audience as much as possible to give yourself the best chance at communicating successfully.

In this chapter you will begin to examine differences between primary, secondary, and hidden audiences. Then, using the AUDIENCE acronym as a tool, you will participate in activities that will help you flesh out information you need to know about your audience in order to persuade, inform, or entertain them. You will have at least three chances to practise your audience analysis skills and get peer feedback. Then, near the end of this chapter, you will craft a message that considers your audience’s needs and expectations. This process will lay the foundation for you to become a communicator who is effective in persuading, informing, or entertaining an audience because you have done your best work in getting to know them, their needs, and expectations first.

Your audience is the person or people you want to communicate with. By knowing more about them (their wants, needs, values, etc.), you are able to better craft your message so that they will receive it the way you intended.

Your success as a communicator partly depends on how well you can tailor your message to your audience.

Your primary audience is your intended audience; it is the person or people you have in mind when you decide to communicate something. However, when analyzing your audience you must also beware of your secondary audience. These are other people you could reasonably expect to come in contact with your message. For example, you might send an email to a customer, who, in this case, is your primary audience, and copy (cc:) your boss, who would be your secondary audience. Beyond these two audiences, you also have to consider your hidden audience, which are people who you may not have intended to come in contact with your audience (or message) at all, such as a colleague who gets a forwarded copy of your email.

An interactive or media element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/foundationsprofcomms/?p=1037

To help you get to know your audience even more, we will begin by working through a set of steps that, together, spell the acronym AUDIENCE. These steps will give you an idea of what questions to ask and what information can be useful in better connecting with your audience.

| A | Analyze | Who is/are the recipients of your message? |

| U | Understand | What is their knowledge about your intended message? |

| D | Demographics | What is their age, gender, education level, position? |

| I | Interest | What is their level of interest/investment in your message (What’s in it for them?) |

| E | Environment | What setting/reality is your audience immersed in, and what is your relationship to it? What is their likely attitude to your message? Have you taken cultural differences into consideration? |

| N | Need | What information does your audience need? |

| C | Customize | How do you adjust your message to your audience? |

| E | Expectations | What are your audience’s expectations? |

These categories of information have been assembled into a job aid to help you conduct your very own audience analyses. As you review the tool, list the traits that apply to you for each section. If you would like to expand this reflection, consider how you might fill this tool out with traits that apply to you in your personal life versus your worklife. What are some methods you might use to find out more about an audience?

For your audience analysis, choose one of the scenarios and fill out the following form. Submit it according to your instructor’s directions.

An interactive or media element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/foundationsprofcomms/?p=1037

NEED THE DOC H5P HERE, BUT N/A

Now let us take a look at putting this tool to use in a scenario. Read the following news story about an executive at a company [http://bit.ly/1Qyqdyy]. Reflect on these questions regarding his email:

| Category of Analysis | Description/Notes |

| Example:To further answer the questions above, we can use the AUDIENCE form to analyze the audience in this scenario and provide a revised message. | |

| AnalyzeWho will receive your message? | Primary: Yahoo employees working on the Daily Fantasy Football development team.Secondary: Other Yahoo employees.

Hidden: Anyone the email could be forwarded to. |

| UnderstandWhat do they already know or understand about your intended message? | Primary: Understands the technical details of Fantasy football.Secondary: May have heard of the project.

Hidden: Knows little of the technical details. |

| DemographicsWhat is their age, gender, education level, occupation, position? | Primary: 20s, 30s, 40s, White/Asian male, educated with bachelors’ or technical degrees and above; mostly IT developers.Secondary: Various ages, gender, mostly educated, and in various positions.

Hidden: Likely an American resident |

| InterestWhat is their level of interest/ investment in your message? (What’s in it for them?) | Primary: Very invested (I’m their boss!).Secondary: Mild interest if they like Fantasy football or the technology behind it.

Hidden: Not very invested. |

| EnvironmentWhat setting/reality is your audience immersed in, and what is your relationship to it? What is their likely attitude to your message? Have you taken cultural differences into consideration? | Primary: Developer setting. Can speak the same IT and corporate culture jargon. Likely to be open to my message because of my position.Secondary: Corporate setting; professionalism expected because of my position. Some may find it funny, others may find it offensive. There may be different corporate cultures in different departments.

Hidden: Could be anyone in the world. Some Americans might find it offensive, others might find it funny. Could potentially include Ice Cube, or other Black people. |

| NeedWhat information does your audience need? How will they use the information? | Primary: Links to get others to participate in the contest staging.Secondary: Instructions on how to get to the staging area for the fantasy football preseason contest staging and explanation of deposit bonus.

Hidden: Information consistent with what they already know about Yahoo’s brand values. |

| CustomizeHow do you adjust your message to better suit your audience? | Primary: Revise to create a more professional tone by removing all references to Ice Cube, hip hop culture, and racially charged elements like Ebonics and the N-word.Secondary: Ensure the contest speaks to the widest variety of employees who can help test the system.

Hidden: Ensure Yahoo’s brand is not damaged, by being above reproach. |

| ExpectationsWhat does your audience expect from you or your message? | Primary: Expects me to be professional and my message to be relevant to their work.Secondary: Expects me to be professional, be competent, and embody company values.

Hidden: Expects me to be professional. |

Subject: Daily Fantasy Football goes live!

Greetings, folks.

Jerry here. I am proud to announce my team is now ready to bring you what you have all been waiting for: Daily Fantasy Football! Starting today, we are going to have NFL preseason contests on staging. Here is how to play:

1) On Desktop: link

2) On iOS: Download the latest dogfood app, which will point to the staging environment.

3) On Android: not yet available

4) Join the Daily Fantasy Football contest before 4 p.m. today: [link]

Please join contests, create contests, invite your friends, and make sure to alert the team at [link] if you find any technical problems.

One more thing: The team is also testing out deposit bonuses! For every dollar you put in, we give you another dollar. If you signed up for Fantasy Football, we give you two dollars. It’s easy money! When you spend money on a contest that runs, your deposit bonus becomes real money at a rate of 4 percent. That means, if you enter a $1 contest, you get 4¢ from your bonus. So try that out and make sure your investment gets returns!

So let’s go for the win-win. Play dogfood Daily Fantasy football so we can all have fun and make some money while we’re at it.

Cheers,

Jerry

When you communicate with an audience, you are normally trying to achieve one or more of the three following broad outcomes:

An interactive or media element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/foundationsprofcomms/?p=1037

An interactive or media element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/foundationsprofcomms/?p=1037

Here are two possible use cases where analyzing your audience will help you improve your communication:

Can you think of others? In both of our suggested use cases, the AUDIENCE tool provides a framework to identify key factors you should consider when creating, revising, or reviewing communications.

Below you will find three scenarios that you can use to practise your ability to identify your audience. Using this Audience Analysis Form, complete an audience analysis for each of the three scenarios below.

An interactive or media element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/foundationsprofcomms/?p=1037

Fill in the Audience Analysis template below and submit it according to your instructor’s directions.

https://h5p.org/h5p/embed/265399

In this chapter you have learned what an audience is and why an awareness of your audience’s needs and expectations is important to communicating your intended message.

You learned to define primary, secondary, and hidden audiences, and thought about ways to persuade, inform, and/or entertain them. You also used the AUDIENCE tool to examine an audience and begin to recognize when the audience and message are mismatched.

You should now be able to create messages that more effectively match your objective to successfully persuade, inform, or entertain. You are also well-positioned to get more practice and/or move on to the next module topic.

An interactive or media element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/foundationsprofcomms/?p=1037

An interactive or media element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/foundationsprofcomms/?p=1037

Wollert Hickman, D. (2014). Audience analysis: Primary, secondary, and hidden audiences. Retrieved from http://writingcommons.org/index.php/2013-12-30-04-56-15/2014-02-04-20-46-53/audience-analysis-primary-secondary-and-hidden-audiences

This chapter is a remix containing content from a variety of sources published under a variety of open licenses, including the following:

4

Upon completing this chapter, you should be able to:

The channel or medium used to communicate a message affects how the audience will receive the message. Communication channels can refer to the methods we use to communicate as well as the specific tools we use in the communication process. In this chapter we will define communication channels as a medium for communication, or the passage of information. In this chapter we will discuss the principal channels of communication, as well as the tools commonly used in professional communication. We will discuss the pros, cons, and use cases for each tool and channel, because, in a professional context, the decision about which channel to use can be a critical one.

Communication channels can be categorized into three principal channels: (1) verbal, (2) written, and (3) non-verbal. Each of these communications channels have different strengths and weaknesses, and oftentimes we can use more than one channel at the same time.

Most often when we think of communication, we might imagine two or more people speaking to each other. This is the largest aspect of verbal communication: speaking and listening. The source uses words to code the information and speaks to the receiver, who then decodes the words for understanding and meaning. One example of interference in this channel is choice of words. If the source uses words that are unfamiliar to the receiver, there is a chance they will miscommunicate the message or not communicate at all. The formality of vocabulary choice is another aspect of the verbal channel. In situations with friends or close co-workers, for example, you may choose more casual words, in contrast to words you would choose for a presentation you are making to your supervisors. In the workplace the primary channel of communication is verbal, much of this communication being used to coordinate with others, problem solve, and build collegiality.

One element of verbal communication is tone. A different tone can change the perceived meaning of a message. Table 1.3.1, “Don’t Use That Tone with Me!” demonstrates just how true that is. If we simply read these words without the added emphasis, we would be left to wonder, but the emphasis shows us how the tone conveys a great deal of information. Now you can see how changing one’s tone of voice can incite or defuse a misunderstanding.

| Placement of Emphasis | Meaning |

| I did not tell John you were late. | Someone else told John you were late. |

| I did not tell John you were late. | This did not happen. |

| I did not tell John you were late. | I may have implied it. |

| I did not tell John you were late. | But maybe I told Sharon and Jose. |

| I did not tell John you were late. | I was talking about someone else. |

| I did not tell John you were late. | I told him you still are late. |

| I did not tell John you were late. | I told him you were attending another meeting. |

Don’t use that tone with me! Based on Kiely, M. (1993)

What you say is a vital part of any communication, but what you don’t say can be even more important. Research also shows that 55 percent of in-person communication comes from non-verbal cues, such as facial expressions, body stance, and smell. According to one study, only 7 percent of a receiver’s comprehension of a message is based on the sender’s actual words; 38 percent is based on paralanguage (the tone, pace, and volume of speech), and 55 percent is based on non-verbal cues such as body language (Mehrabian, 1981).

Research shows that non-verbal cues can also affect whether you get a job offer. Judges examining videotapes of actual applicants were able to assess the social skills of job candidates with the sound turned off. They watched the rate of gesturing, time spent talking, and formality of dress to determine which candidates would be the most successful socially on the job (Gifford, Ng, and Wilkinson, 1985). For this reason, it is important to consider how we appear in the professional environment as well as what we say. Our facial muscles convey our emotions. We can send a silent message without saying a word. A change in facial expression can change our emotional state. Before an interview, for example, if we focus on feeling confident, our face will convey that confidence to an interviewer. Adopting a smile (even if we are feeling stressed) can reduce the body’s stress levels.

Generally speaking, simplicity, directness, and warmth convey sincerity, and sincerity is key to effective communication. A firm handshake given with a warm, dry hand is a great way to establish trust. A weak, clammy handshake conveys a lack of trustworthiness. Gnawing one’s lip conveys uncertainty. A direct smile conveys confidence. All of this is true across North America. However, in other cultures the same firm handshake may be considered aggressive and untrustworthy. It helps to be mindful of cultural context when interpreting or using body language.

Smell is an often overlooked but powerful non-verbal communication method. Take the real estate agent who sprinkles cinnamon in boiling water to mimic the smell of baked goods in her homes, for example. She aims to increase her sales by using a smell to create a positive emotional response that invokes a warm, homelike atmosphere for her clients. As easy as it is for a smell to make someone feel welcome, the same smell may be a complete turnoff to someone else. Some offices and workplaces in North America ban the use of colognes, perfumes, or other fragrances to aim for a scent-free work environment (some people are allergic to such fragrances). It is important to be mindful that using a strong smell of any kind may have an uncertain effect, depending on the people, culture, and other environmental norms.

In business, the style and duration of eye contact people consider appropriate varies greatly across cultures. In the Canadian culture, looking someone in the eye (for about a second) is considered a sign of trustworthiness. However, in other countries, eye is perceived differently. For instance, in Asian culture, eye contact can be seen as insubordinate e.g., between student and teacher.

The human face can produce thousands of different expressions. Experts have decoded these expressions as corresponding to hundreds of different emotional states (Ekman, Friesen, and Hager, 2008). Our faces convey basic information to the outside world. Happiness is associated with an upturned mouth and slightly closed eyes; fear, with an open mouth and wide-eyed stare. Flitting (“shifty”) eyes and pursed lips convey a lack of trustworthiness. The effect facial expressions have on conversation is instantaneous. Our brains may register them as “a feeling” about someone’s character.

The position of our body relative to a chair or another person is another powerful silent messenger that conveys interest, aloofness, professionalism—or lack thereof. Head up, back straight (but not rigid) implies an upright character. In interview situations, experts advise mirroring an interviewer’s tendency to lean in and settle back in her seat. The subtle repetition of the other person’s posture conveys that we are listening and responding.

In contrast to verbal communications, written professional communications are textual messages. Examples of written communications include memos, proposals, emails, letters, training manuals, and operating policies. They may be printed on paper, handwritten, or appear on the screen. Normally, a verbal communication takes place in real time. Written communication, by contrast, can be constructed over a longer period of time. Written communication is often asynchronous (occurring at different times). That is, the sender can write a message that the receiver can read at any time, unlike a conversation that transpires in real time. There are exceptions, however; for example, a voicemail is a verbal message that is asynchronous. Many jobs involve some degree of writing. Luckily, it is possible to learn to write clearly (more on this in the Plain Language chapter and the writing module).

The three principal communication channels can be used “in the flesh” and in digital formats. Digital channels extend from face-to-face to video conferencing, from written memos to emails, and from speaking in person to using telephones. The digital channels retain many of the characteristics of the principal channels but influence different aspects of each channel in new ways. The choice between analog and digital can affect the environment, context, and interference factors in the communication process.

An interactive or media element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/foundationsprofcomms/?p=1074

Information richness refers to the amount of sensory input available during a communication. For example, speaking to a colleague in a monotone voice with no change in pacing or gestures does not make for a very rich experience. On the other hand, if you use gestures, tone of voice, pace of speech, etc., to communicate meaning beyond the words themselves, you facilitate a richer communication. Channels vary in their information richness. Information-rich channels convey more non-verbal information. For example, a face-to-face conversation is richer than a phone call, but a phone call is richer than an email. Research shows that effective managers tend to use more information-rich communication channels than do less effective managers (Allen and Griffeth, 1997; Fulk and Body, 1991; Yates and Orlikowski, 1992). The figure below illustrates the information richness of different information channels.

| Channel | Information Richness |

| Face-to-face conversation | High |

| Videoconferencing | High |

| Telephone | High |

| Medium | |

| Mobile devices | Medium |

| Blogs | Medium |

| Letter | Medium |

| Written documents | Low |

| Spreadsheets | Low |

Adapted from Daft and Lenge, 1984; Lengel and Daft, 1988

Like face-to-face and telephone conversation, videoconferencing has high information richness because receivers and senders can see or hear beyond just the words—they can see the sender’s body language or hear the tone of their voice. Mobile devices, blogs, letters, and memos offer medium-rich channels because they convey words and images. Formal written documents, such as legal documents and spreadsheets (e.g., the division’s budget), convey the least richness, because the format is often rigid and standardized. As a result, nuance is lost.

When determining whether to communicate verbally or in writing, ask yourself, Do I want to convey facts or feelings? Verbal communications are a better way to convey feelings, while written communications do a better job of conveying facts.

Picture a manager delivering a speech to a team of 20 employees. The manager is speaking at a normal pace. The employees appear interested. But how much information is the manager transmitting? Not as much as the speaker believes! Humans listen much faster than they speak.

The average public speaker communicates at a speed of about 125 words per minute. That pace sounds fine to the audience, but faster speech would sound strange. To put that figure in perspective, someone having an excited conversation speaks at about 150 words per minute. Based on these numbers, we could assume that the employees have more than enough time to take in each word the manager delivers. But that is the problem. The average person in the audience can hear 400–500 words per minute (Leed and Hatesohl, 2008). The audience has more time than they need. As a result, they will each be processing many thoughts of their own, on totally different subjects, while the manager is speaking. As this example demonstrates, verbal communication is an inherently flawed medium for conveying specific facts. Listeners’ minds wander. Once we understand this fact, we can make more intelligent communication choices based on the kind of information we want to convey.

The key to effective communication is to match the communication channel with the goal of the message (Barry and Fulmer, 2004). Written media is a better choice when the sender wants a record of the content, has less urgency for a response, is physically separated from the receiver, does not require much feedback from the receiver, or when the message is complicated and may take some time to understand.

Verbal communication makes more sense when the sender is conveying a sensitive or emotional message, needs feedback immediately, and does not need a permanent record of the conversation. Use the guide provided for deciding when to use written versus verbal communication.

| Use Written | Use Verbal |

| to convey facts | to convey emotions |

| to provide a permanent record | when you do not need a permanent record |

| when you do not need a timely response | when the matter is urgent |

| when you do not need immediate feedback | when you need immediate feedback |

| to explain complicated ideas | for simple, easy-to-explain ideas |

Written versus Verbal Communication

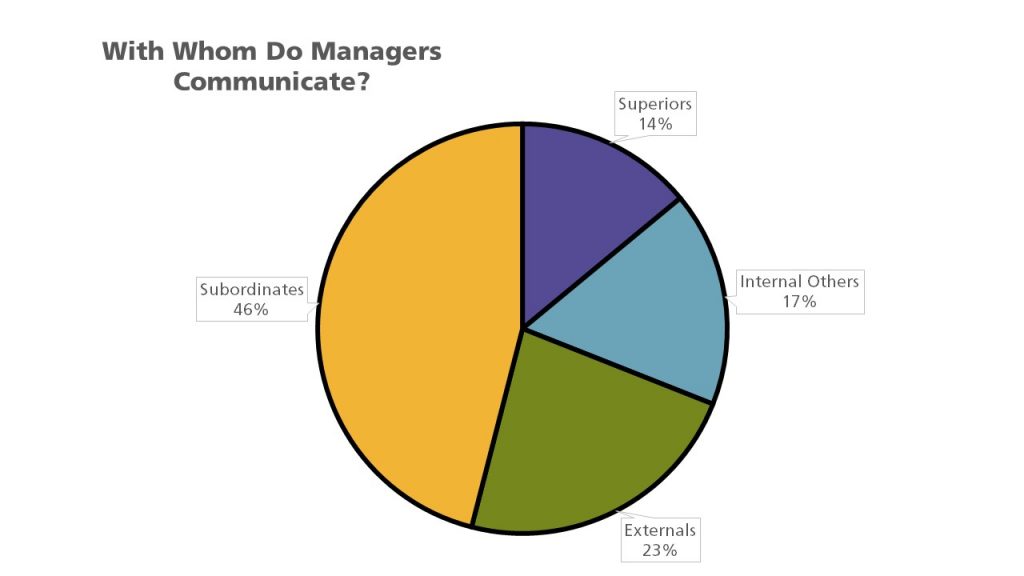

Information can move sideways, from a sender to a receiver—for example, from you to your colleague. It can also move upward, such as to a superior; or downward, such as from management to subordinates.

The status of the sender can affect the receiver’s attentiveness to the message. For example, a senior manager sends a memo to a production supervisor. The supervisor, who has a lower status within the organization, will likely pay close attention to the message. But the same information conveyed in the opposite direction might not get the same attention. The message would be filtered by the senior manager’s perception of priorities and urgencies.

Requests are just one kind of communication in a professional environment. Other communications, both verbal or written, may seek, give, or exchange information. Research shows that frequent communications with one’s supervisor is related to better job performance ratings and overall organizational performance (Snyder and Morris, 1984; Kacmar, Witt, Zivnuska and Guly, 2003). Research also shows that lateral communication done between peers can influence important organizational outcomes such as turnover (Krackhardt and Porter, 1986).

With Whom Managers Spend Time Communicating At Work by L. Underwood. Adapted from Luthans and Larsen, 1986

External communications deliver messages to individuals outside an organization. They may announce changes in staff, strategy, or earnings to shareholders; or they might be service announcements or ads for the general public, for example. The goal of an external communication is to create a specific message that the receiver will understand and/or share with others. Examples of external communications include the following:

Public relations professionals create external communications about a client’s product, services, or practices for specific receivers. These receivers, it is hoped, will share the message with others. In time, as the message is passed along, it should appear to be independent of the sender, creating the illusion of an independently generated consumer trend or public opinion.

The message of a public relations effort may be B2B (business to business), B2C (business to consumer), or media related. The message can take different forms. Press releases try to convey a newsworthy message, real or manufactured. It may be constructed like a news item, inviting editors or reporters to reprint the message, in part or as a whole, and with or without acknowledgment of the sender’s identity. Public relations campaigns create messages over time, through contests, special events, trade shows, and media interviews in addition to press releases.

Advertisements present external business messages to targeted receivers. Advertisers pay a fee to a television network, website, or magazine for an on-air, site, or publication ad. The fee is based on the perceived value of the audience who watches, reads, or frequents the space where the ad will appear.

In recent years, receivers (the audience) have begun to filter advertisers’ messages through technology such as ad blockers, the ability to fast-forward live or recorded TV through PVRs, paid subscriptions to Internet media, and so on. This trend grew as a result of the large amount of ads the average person sees each day and a growing level of consumer weariness of paid messaging. Advertisers, in turn, are trying to create alternative forms of advertising that receivers will not filter. For example, The advertorial is one example of an external communication that combines the look of an article with the focused message of an ad. Product placements in videos, movies, and games are other ways that advertisers strive to reach receivers with commercial messages.

A website may combine elements of public relations, advertising, and editorial content, reaching receivers on multiple levels and in multiple ways. Banner ads and blogs are just a few of the elements that allow a business to deliver a message to a receiver online. Online messages are often less formal and more approachable, particularly if intended for the general public. A message relayed in a daily blog post will reach a receiver differently than if it is delivered in an annual report, for example.

The popularity and power of blogs is growing. In fact, blogs have become so important to some companies as Coca-Cola, Kodak, and Marriott that they have created official positions within their organizations titled Chief Blogging Officer (Workforce Management, 2008). The real-time quality of web communications may appeal to receivers who filter out a traditional ad and public relations message because of its prefabricated quality.

Customer communications can include letters, catalogues, direct mail, emails, text messages, and telemarketing messages. Some receivers automatically filter bulk messages like these; others will be receptive. The key to a successful external communication to customers is to convey a business message in a personally compelling way—dramatic news, a money-saving coupon, and so on. Customers will think What’s in it for me? when deciding how to respond to these messages, so clear benefits are essential.

Different communication channels are more or less effective at transmitting different kinds of information. Some types of communication range from high richness in information to medium and low richness. In addition, communications flow in different directions within organizations. A major internal communication channel is email, which is convenient but needs to be handled carefully. External communication channels include PR/press releases, ads, websites, and customer communications such as letters and catalogues.

You should aim for 100% on these five questions to ensure you understand key concepts.

An interactive or media element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/foundationsprofcomms/?p=1074

5

Upon completing this chapter, you should be able to:

No matter who your audience is, they will appreciate your ability to write using plain language. This is a key skill in any professional setting. Plain language writing—and speaking—will help you to get your message across clearly and concisely. This chapter will introduce you to the principles of plain language and allow you to practise them.

To communicate professionally, you need to know when and how to use either active or passive voice. Although most contexts prefer the active voice, the passive voice may be the best choice in certain situations. Generally, though, passive voice tends to be awkward, vague, wordy, and a grammatical construct you should avoid in most cases.

To use active voice, make the noun that performs the action the subject of the sentence and pair it directly with an action verb.

Read these two sentences:

Matt Damon left Harvard in the late 1980s to start his acting career.

Matt Damon’s acting career was started in the late 1980s when he left Harvard.

In the first sentence, left is an action verb that is paired with the subject, Matt Damon. If you ask yourself, “Who or what left?” the answer is Matt Damon. Neither of the other two nouns in the sentence—Harvard and career—”left” anything.

Now look at the second sentence. The action verb is started. If you ask yourself, “Who or what started something?” the answer, again, is Matt Damon. But in this sentence, the writer placed career—not Matt Damon—in the subject position. When the doer of the action is not the subject, the sentence is in passive voice. In passive voice constructions, the doer of the action usually follows the word by as the indirect object of a prepositional phrase, and the action verb is typically partnered with a version of the verb to be.

The following sentences are in passive voice. For each sentence, identify

An interactive or media element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/foundationsprofcomms/?p=1094

An interactive or media element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/foundationsprofcomms/?p=1094

Decide whether each of the following sentences is active or passive.

An interactive or media element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/foundationsprofcomms/?p=1094

Two sentences can say the same thing but leave a different impression based on the choice of verb. Which of the following sentences gives you the most vivid mental picture?

Most of us would agree that sentence B paints a better picture.

Try to express yourself with action verbs instead of forms of the verb to be. Sometimes it is fine to use forms of the verb to be, such as is or are, but it is easy to overuse them (as in this sentence—twice). Overuse of these verbs will make your writing dull.

Read each of the following sentences and note the use of the verb to be. Think of a way to reword the sentence to make it more interesting by using an action verb before you expand to view the suggested revision.

An interactive or media element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/foundationsprofcomms/?p=1094

A point of confusion that sometimes comes up when people discuss the passive voice is the use of expletive pronouns. A sentence with expletive pronouns often starts with “There is …” or “There are ….” Many people mistakenly think that expletive pronoun sentences are a form of passive voice, but they are not.

To understand the difference, please read the “Avoid Expletive Pronouns” section under Principle 5.

Even though the passive voice might include an action verb, the action verb is not as strong as it could be, because of the sentence structure. The passive voice also causes unnecessary wordiness. Read the following sentences and think of a way to reword each using an action verb in active voice. Then look at the suggested revision for each case.

An interactive or media element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/foundationsprofcomms/?p=1094

Writing in active voice is easy once you understand the difference between active and passive voice. Make sure you always define who or what did what. If you use forms of the verb to be with your action verb, consider the reason for your choice. If you are writing in progressive tense (“Carrie is walking to my house”) or perfect progressive tense (“Melissa will have been married for four years by then”), you will need to use helping verbs, even in active voice.

Sometimes passive voice is the best option. Consider the following acceptable uses of passive voice.

When you do not know who or what is responsible for the action:

Example: Our front-door lock was picked.

Rationale: If you do not know who picked the lock on your front door, you cannot say who did it. You could say a thief broke in, but that would be an assumption; you could, theoretically, find out that the lock was picked by a family member who had forgotten to take a key.

When you want to hide the person or thing responsible for the action, such as in a story:

Example: The basement was filled with a mysterious scraping sound.

Rationale: If you are writing a dramatic story, you might introduce a phenomenon without revealing the person or thing that caused it.

When the person or thing that performed the action is not important:

Example: The park was flooded all week.

Rationale: Although you would obviously know that the rainwater flooded the park, saying so would not be important.

When you do not want to place credit, responsibility, or blame:

Example: A mistake was made in the investigation that resulted in the wrong person being on trial.

Rationale: Even if you think you know who is responsible for a problem, you might not want to expose the person.

When you want to maintain the impression of objectivity:

Example: It was noted that only first-graders chose to eat the fruit.

Rationale: Research reports in certain academic disciplines attempt to remove the researcher from the results, to avoid saying, for example, “I noted that only first graders….”

When you want to avoid using a gendered construction, and pluralizing is not an option:

Example: If the password is forgotten by the user, a security question will be asked.

Rationale: This construction avoids the need for the cumbersome “his or her” (as in “the user forgets his or her password”).

Inappropriate word choices will get in the way of your message. For this reason, use language that is accurate and appropriate for the writing situation. Omit jargon (technical words and phrases common to a specific profession or discipline) and slang (invented words and phrases specific to a certain group of people), unless your audience and purpose call for such language. Avoid using outdated words and phrases, such as “Dial the number.” Be straightforward in your writing rather than using euphemism (a gentler, but sometimes inaccurate, way of saying something). Be clear about the level of formality each piece of writing needs, and adhere to that level.

Jargon and slang both have their places. Using jargon is fine as long as you can safely assume your readers also know the jargon. For example, if you are a lawyer writing to others in the legal profession, using legal jargon is perfectly fine. On the other hand, if you are writing for people outside the legal profession, using legal jargon would most likely be confusing, and you should avoid it. Of course, lawyers must use legal jargon in papers they prepare for customers. However, those papers are designed to navigate within the legal system and may not be clear to readers outside of this demographic.

Examples:

Jargon: I need to hammer out this report by tomorrow.

Alternative: I need to type up this report by tomorrow.

Euphemism: My uncle is vertically challenged.

Alternative: My uncle is only five feet tall.

Unless there is a specific reason not to, use positive language wherever you can. Positive language benefits your writing in two ways. First, it creates a positive tone, and your writing is more likely to be well-received. Second, it clarifies your meaning, as positive statements are more concise. Take a look at the following negatively worded sentences and then their positive counterparts, below.

Examples:

Negative: Your car will not be ready for collection until Friday.

Positive: Your car will be ready for collection on Friday.

Negative: You did not complete the exam.

Positive: You will need to complete the exam.

Negative: Your holiday time is not approved until your manager clears it.

Positive: Your holiday time will be approved when your manager clears it.

Avoid using multiple negatives in one sentence, as this will make your sentence difficult to understand. When readers encounter more than one negative construct in a sentence, their brains have to do more cognitive work to decipher the meaning; multiple negatives can create convoluted sentences that bog the reader down.

Examples:

Negative: A decision will not be made unless all board members agree.

Positive: A decision will be made when all board members agree.

Negative: The event cannot be scheduled without a venue.

Positive: The event can be scheduled when a venue has been booked.

When you write for your readers and speak to an audience, you have to consider who they are and what they need to know. When readers know that you are concerned with their needs, they are more likely to be receptive to your message, and will be more likely to:

Your message will mean more to your reader if they get the impression that it was written directly to them. When you sit down to write, either for a paper or a presentation, consider the audience analysis tool presented earlier in this module.

Then try to answer these questions in your writing with user-friendly language. Speaking directly to the audience using you-oriented language helps to personalize the message and make it easier to understand. Using the second-person pronoun you tells your reader that the message is intended for them. You might be inclined to use he, she, or they instead, but those terms are not as direct or personal. Using the pronoun you makes the message feel relevant.

Consider the following sentences:

Which one is more inviting? Most people will find the second sentence more friendly and inviting because it addresses the reader directly.

When you write, ask yourself, “Why would someone read this message?” Often, it is because the reader needs a question answered. What do they need to know to prepare for the upcoming meeting, for example, or what new company policies do they need to abide by? Think about the questions your readers will ask and then organize your document to answer them.

It is easy to let your sentences become cluttered with words that do not add value to your message. Improve cluttered sentences by eliminating repetitive ideas, removing repeated words, and editing to eliminate unnecessary words.

Unless you are providing definitions on purpose, stating one idea twice in a single sentence is redundant. Read each example below and think about how you could revise the sentence to remove repetitive phrasing. Then look at the suggested revision.

Examples:

Original: Use a very heavy skillet made of cast iron to bake an extra-juicy meatloaf.

Revision: Use a cast-iron skillet to bake a juicy meatloaf.

Original: Joe thought to himself, I think I’ll make caramelized grilled salmon tonight.

Revision: Joe thought, I think I’ll make caramelized grilled salmon tonight.

As a general rule, you should try not to repeat a word within a sentence. Sometimes you simply need to choose a different word. But often you can actually remove repeated words. Read this example and think about how you could revise the sentence to remove a repeated word that adds wordiness. Then check out the revision below the sentence.

Example:

Original: The student who won the cooking contest is a very talented and ambitious student.

Revision: The student who won the cooking contest is very talented and ambitious.

If a sentence has words that are not necessary to carry the meaning, those words are unneeded and can be removed. Read each example and think about how you could revise the sentence; then check out the suggested revisions.

Examples:

Original: Andy has the ability to make the most fabulous twice-baked potatoes.

Revision: Andy makes the most fabulous twice-baked potatoes.

Original: For his part in the cooking class group project, Malik was responsible for making the mustard reduction sauce.

Revision: Malik made the mustard reduction sauce for his cooking class group project.

Many people create needlessly wordy sentences using expletive pronouns, which often take the form of “There is …” or “There are ….”

Now, if you remember, pronouns (e.g., I, you, he, she, they, this, that, who, etc.) are words that we use to replace nouns (i.e., people, places, things), and there are many types of pronouns (e.g., personal, relative, demonstrative, etc.). However, expletive pronouns are different from other pronouns because unlike most pronouns, they do not stand for a person, thing, or place; they are called expletives because they have no “value.” Sometimes you will see expletive pronouns at the beginning of a sentence, sometimes at the end. Look at the following expletive constructs:

Examples:

The main reason we should generally avoid writing with expletive pronouns is that they often cause us to use more words in the rest of the sentence than we have to. Also, the empty words at the beginning tend to shift the more important subject matter toward the end of the sentence. The above sentences are not that bad, but at least they are simple enough to help you understand what expletive pronouns are. Here are some more examples of expletive pronouns, along with better alternatives.

Examples

Original: There are some people who love to cause trouble.

Revision: Some people love to cause trouble.

Original: There are some things that are just not worth waiting for.

Revision: Some things are just not worth waiting for.

Original: There is a person I know who can help you fix your computer.

Revision: I know a person who can help you fix your computer

While not all instances of expletive pronouns are bad, writing sentences with expletives seems to be habit forming. It can lead to trouble when you are explaining more complex ideas, because you end up having to use additional strings of phrases to explain what you want your reader to understand. Wordy sentences, such as those with expletive pronouns, can tax the reader’s mind.

Example

Original: There is a button you need to press that is red and says STOP.

Revision: You need to press the red STOP button. Or: Press the red STOP button.

Of course, most rules and guideline have exceptions, and expletive pronouns are no different. In many cases common expressions, particularly if they are short, are not worth revising—especially in live communications such as presentations, lectures, and speeches.

Examples:

There is no place I’d rather be.

There are good days, and there are bad days.

There is no way around this.

How many ways are there to solve this puzzle?

The above sentences use expletive pronouns but are fine because they are short and easy on the reader’s mind. In fact, revising them would make for longer, more convoluted sentences!

So when you find yourself using expletives, always ask yourself if omitting and rewriting would give your reader a clearer, more direct, less wordy sentence. Can I communicate the same message using fewer words without taking away from the meaning I want to convey or the tone I want to create? Practise evaluating your own writing and playing with alternative ways to say the same thing.

Do not confuse expletive pronouns with passive voice (as also noted briefly in Principle 1: Use the Active Voice). Both expletive sentences and passive voice use forms of the verb to be, often result in wordiness, and sometimes obscure important information, but they are not the same thing grammatically. The following example should help to clear up any mix-up between the two.

Example:

The following sentence uses passive voice:

It is passive because the subject of the sentence (people) are not the doers of the verb called. The active agent who will be “calling” is missing. Are you to call upon these people, or will someone else call upon them?

But the following example uses an expletive pronoun and is not in passive voice, because it has an active agent (you) doing the “calling”:

But even though passive voice and expletive constructs are not the same, it is possible—but rarely advisable—to write a sentence that uses both!

The active agent doing the “calling” is, once again, missing; and the sentence starts with the expletive “There are.” What a convoluted sentence!

A better sentence that uses neither passive voice nor expletive pronouns would be:

Ah! Much better!

In this chapter, you have recognized plain language as a way to get your message across clearly and concisely when writing and speaking. You have identified five principles of plain-language writing: use active voice, use common words instead of complex words, use a positive tone when possible, write for your reader, and keep words and sentences short. You should now be ready to get more practice using the questions in this chapter, or move on to the next topic.

Aim to achieve 100% on these final, check in questions. Good luck!

An interactive or media element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/foundationsprofcomms/?p=1094

Attribution Statement (Plain Language)

This chapter is a remix containing content from a variety of sources published under a variety of open licenses, including the following:

6

Upon completing this chapter, you should be able to:

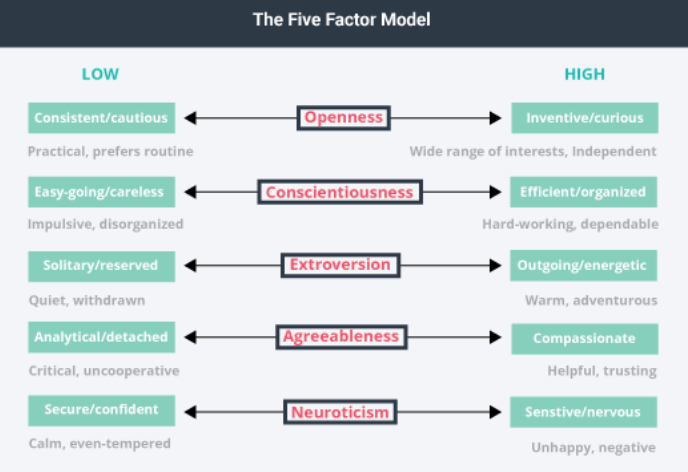

It may be a cliché to say, “A picture is worth a thousand words,” but visual images have power. Good communication is a multisensory experience. Children first learning how to read often gravitate toward books with engaging pictures. As adults we graduate to denser books without pictures, yet we still visualize ideas to help us understand the text. Advertisers favour visual media—television, magazines, and billboards—because they are the best way to hook an audience. Websites rely on colour, graphics, icons, and a clear system of visual organization to engage Internet surfers. Visuals bring ideas to life for many readers and audiences in multiple ways:

Source: (Picardi, 2001)

This chapter discusses how to use different kinds of visual aids effectively.

In this chapter we will be focusing on the following types of visuals:

Source: (Saunders, 1994)

We will describe these in more detail below:

Symbols: Symbols include a range of items that can be either pictographic or abstract. We are surrounded by symbols, but how often do you think about the symbols that communicate with you everyday? What symbols can you see right now in your surroundings? Maybe the icons for the apps on your phone are familiar symbols to you. How about the TV remote control, which uses symbols to indicate the function of its buttons. Company logos lead you to identify the brand before you even read any words. Or look at the tags on your clothing; they use symbols to tell you how to wash and dry the garments as intended.

Icons in Everyday Life by L. Underwood

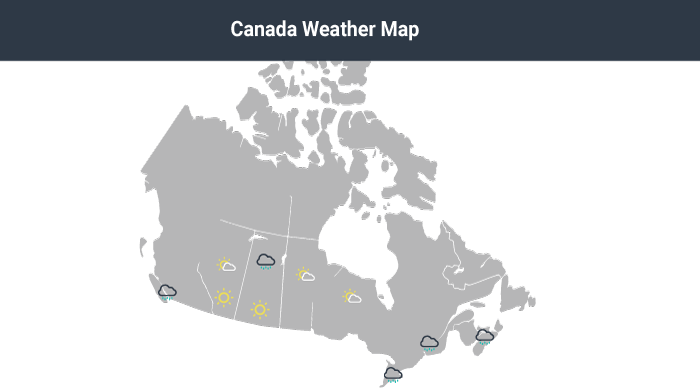

Maps: Maps sometimes include map charts, or statistical maps. Maps are often used to communicate geographical and other information in one visual (Picardi, 2001).

Canada Weather Map by L. Underwood

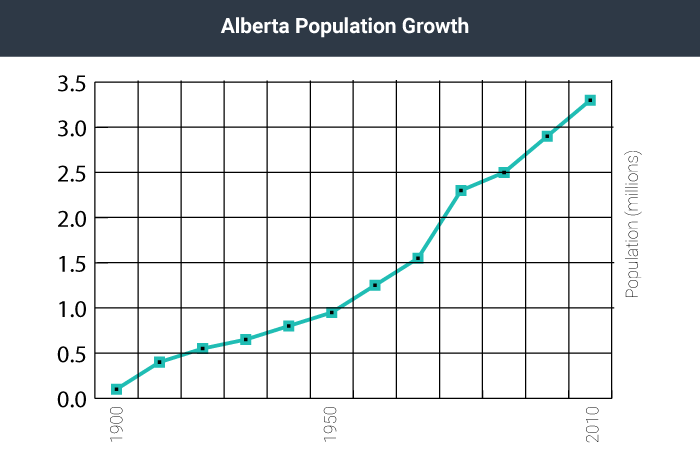

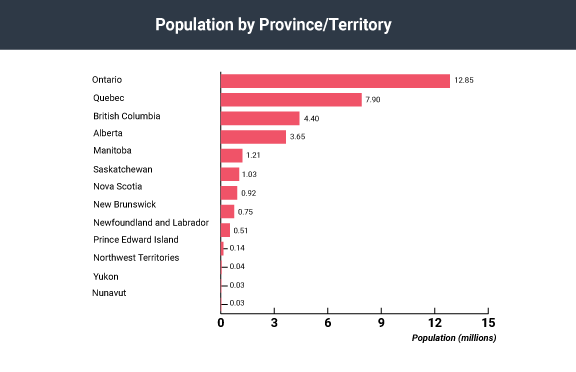

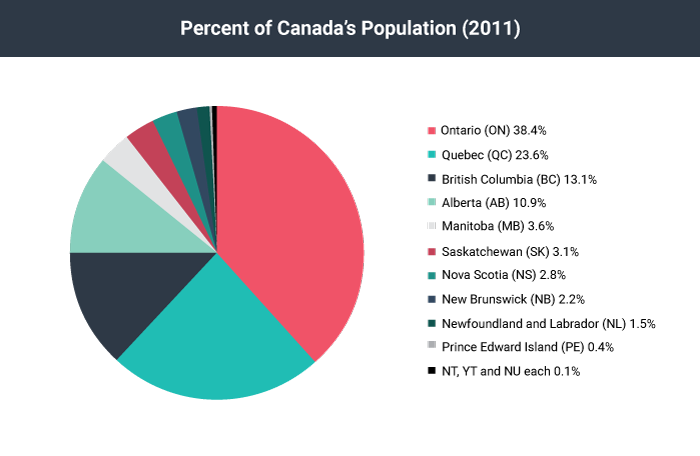

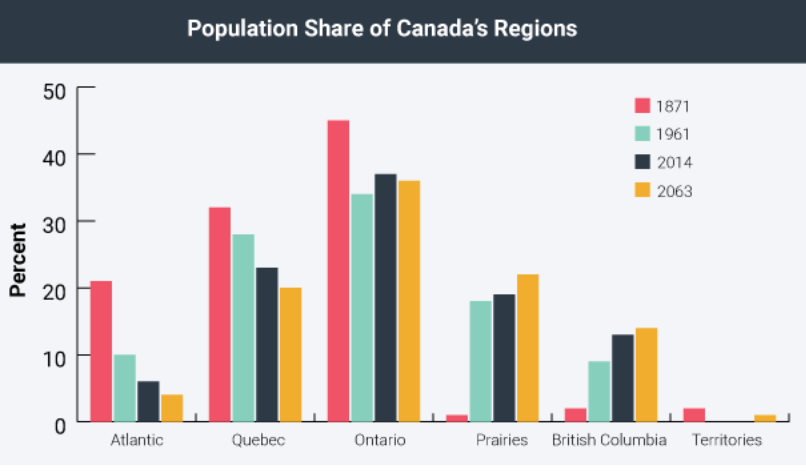

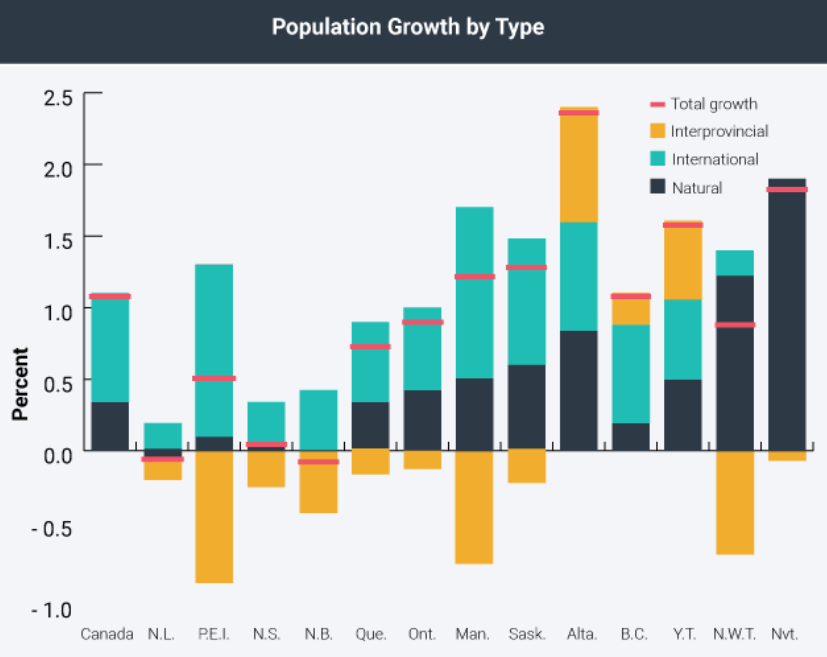

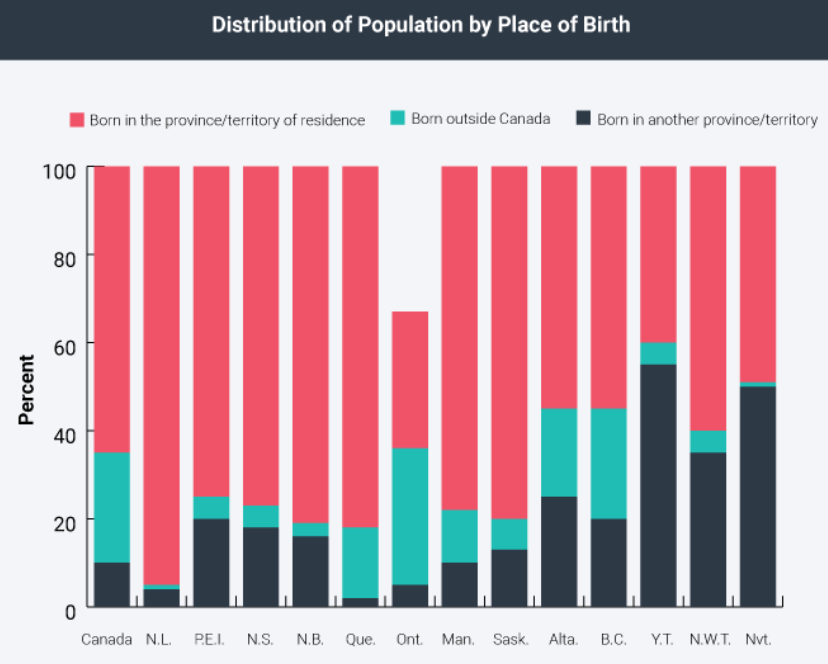

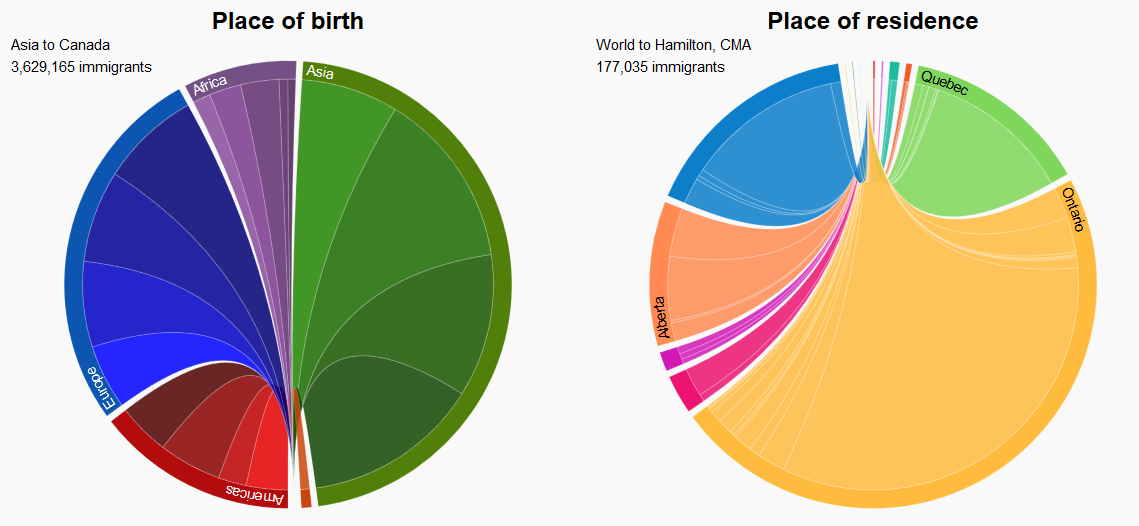

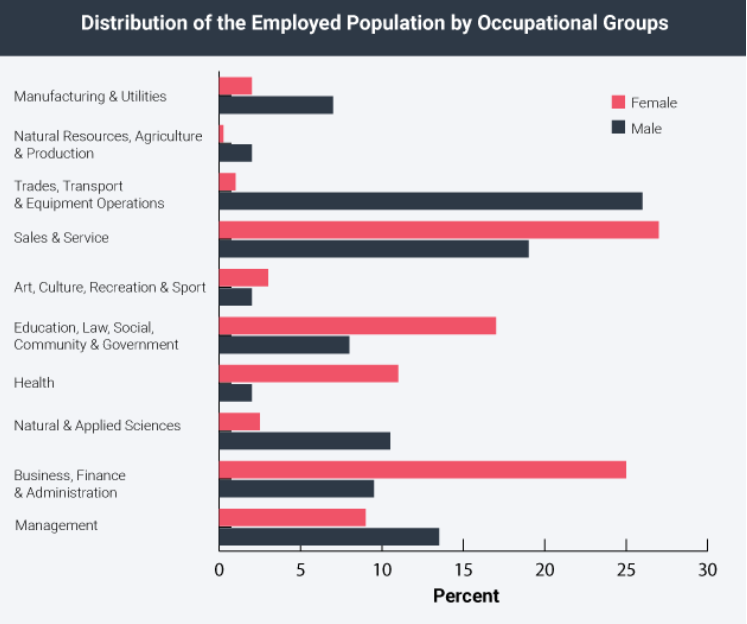

Graphs and Tables: Graphs can take a variety of forms, the most common being line graphs, bar graphs, and pie charts. Each type is better suited to different situations and purposes. For example, line graphs show change quickly, while bar charts are effective to compare data, and pie charts visualize the relation between parts and the whole (Picardi, 2001). Tables can be more effective for situations that call for qualitative data (not just numbers).

Population Growth Line Graph by L. Underwood

Canadian Population Bar Graph by L. Underwood

Percent of Canada’s Population by L. Underwood

Tip: If you are working with numerical information, consider whether a pie chart, bar graph, or line graph might be an effective way to present the content. A table can help you organize numerical information, but it is not the most effective way to emphasize contrasting data or to show changes over time.

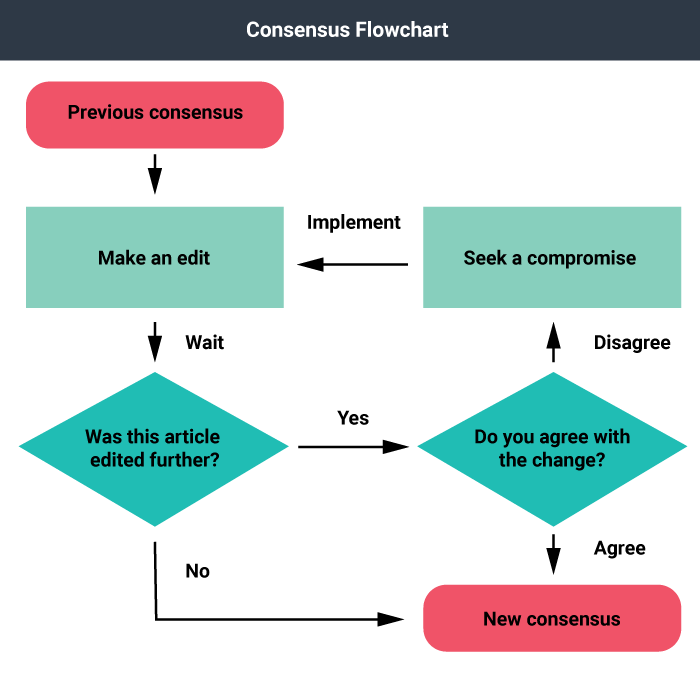

Diagrams: Saunders (1994) describes diagrams as “visuals drawn to represent and identify parts of a whole, a process, a general scheme, and/or the flow of results of an action or process.” One example of a diagram would be a flow chart. Flow charts are often used to show physical processes, such as in a manufacturing facility, or in the decision making procedures of a larger corporation, for example. Flow charts combine the use of text, colour, and shapes to indicate various functions performed in a process.

Consensus Flowchart by L Underwood

Photographs: Photographs (still or moving) depict concrete objects, tell a story, provide a scenario, and persuade an audience.

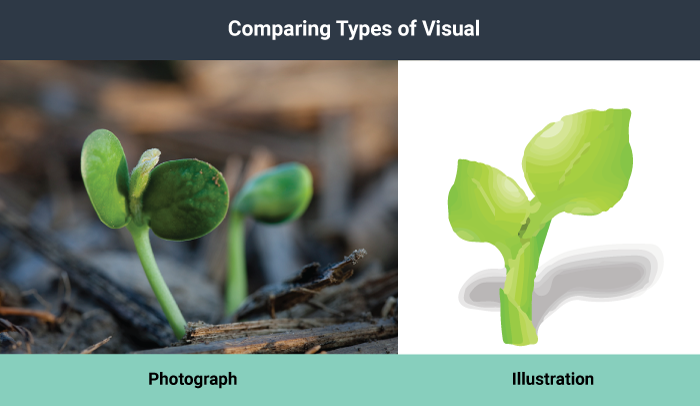

Illustrations: Illustrations can be realistic or abstract. There are instances where a photograph may be too rich in visual elements and a simpler line drawing communicates more quickly and clearly. For example, next time you are in a public building, look around for the fire escape plan. Is it a photograph or a line drawing? Illustrations offer a simpler visual and can be easier to understand than photographs because they filter out unnecessary information.

Comparing Types of Visual by L, Underwood

There are a number of reasons you might consider including visuals in documents, presentations, and other communications. Four reasons are detailed below:

Decorative: Visuals that do not represent objects or actions within the text but are added, instead, for aesthetic effect are considered decorative. Decorative visuals are often added to gain attention or increase the audience’s interest. Visuals can be used this way but can detract from the message you are trying to communicate and, thus, should be used with caution.

Representational: These visuals physically represent or physically resemble objects or actions in the text and are relevant to the content of the text. For example, rather than giving a detailed textual description of a new playground, you might include an image or render of the new playground and use the text to highlight specific features or information.

Analogical: Analogical visuals are used to compare and contrast two things, and explain their likeness or correspondence. For example, a marketing consultant might try to clarify the difference between targeted marketing and mass marketing by including images of a single fisherman with a single fishing rod and line next to an image of a bigger boat with a fishing net. By using the fishing analogy, the marketing consultant is attempting to connect possible prior understanding of the audience, a visual, and the concepts of targeted marketing versus mass marketing.

Organizational: The purpose of organizational images is to provide structure to information, visually define relationships, and illustrate connections. A chart of the hierarchical structure of a company is one example of an organizational image.

Communication professionals have offered their visual preferences for various communication needs. See if you match or agree with their recommendations.

An interactive or media element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here: https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/foundationsprofcomms/?p=1111

There are many considerations to keep in mind when choosing visuals. When possible, use a variety of types of visuals, but remember that any visuals you use should enhance the content of the text. For example, only add photos if viewing the photos will clarify the text. Near each visual, explain its purpose concisely. Do not expect your readers to figure out the values of the visuals on their own.

You have three choices for finding visuals to use in your work. You can search the Internet, use photos you have taken, or create images yourself.

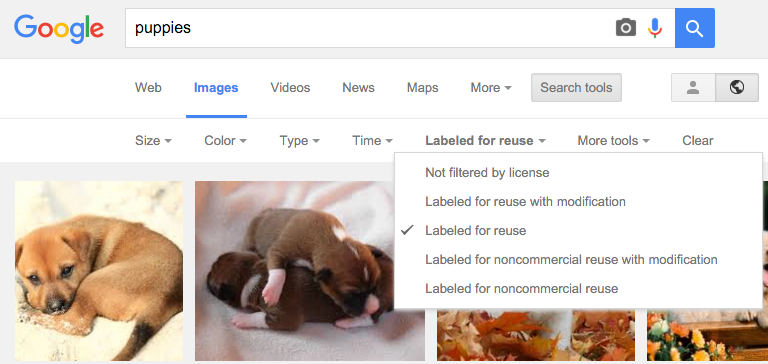

The Internet is a powerful tool you can use to find visuals to complement your work. If you simply click on “images” for your topic in a search engine, you will generate both royalty-free and copyright-protected images. However, if you include a term such as stock images, stock photos, or royalty-free images along with your topic, you will be able to narrow your search to royalty-free items. Some search engines can help you filter your search by license type as well. For example, Google images includes a search tool that allows you to filter the results by license type. We should mention, however, that this tool is not perfect, and you should check the source of the image directly for its licensing requirements. You should not take an image from a search engine unless you are sure that the creator has provided a license that allows you to do so.

Google Image Search Tools Screenshot from Google

When searching Google Images, you can search for images with specific permissions by clicking “Search Tools,” then “Usage Rights.”

You could also use a stock photo website that provides pay-per-use professional photos. Even on these sites you also need to be sure that the creator has provided a license for the image to be used freely in the way you intend to use it (for example, under a Creative Commons license).

Any time an individual or group creates something, such as a visual, they automatically have the rights to that visual and copies of it (i.e., copyright). They do not need to register with any organization in order to get the copyrights for their work; it is assumed as soon as they create it. This means that others are required to seek permission, and often pay a fee, n order to use the work. For example, a photographer might sell one of their photos to a magazine under the condition that they will be paid based on the number of copies printed or sold.

Any time an individual or group creates something, such as a visual, they automatically have the rights to that visual and copies of it (i.e., copyright). They do not need to register with any organization in order to get the copyrights for their work; it is assumed as soon as they create it. This means that others are required to seek permission, and often pay a fee, n order to use the work. For example, a photographer might sell one of their photos to a magazine under the condition that they will be paid based on the number of copies printed or sold.

Creative Commons is a way for creators to share their work with fewer restrictions than copyright alone. There are four distinct conditions available in a Creative Commons license: attribution, share-alike, non-commercial, and no derivatives. Upon creating a work, an author may attach a Creative Commons license that offers a combination of these conditions. The table below outlines the conditions in more detail.

Creative Commons is a way for creators to share their work with fewer restrictions than copyright alone. There are four distinct conditions available in a Creative Commons license: attribution, share-alike, non-commercial, and no derivatives. Upon creating a work, an author may attach a Creative Commons license that offers a combination of these conditions. The table below outlines the conditions in more detail.

Match the images of Creative Commons licenses with what you would be allowed to do with a work bearing that license.

An interactive or media element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here: https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/foundationsprofcomms/?p=1111

When using Creative Commons works, ensure you follow the requirements that the work you are using is licensed under. This often includes identifying the original creator and a link to the Creative Commons license itself.

An image may also be in the Public Domain, meaning that the creator’s intellectual property rights have expired, been forfeited, or are inapplicable. In this case, the image is free to use globally without restriction.

For guidance on how to find Creative Commons materials, using the creative common search portal, see How to Find Creative Commons Materials Using the Creative Commons Search Portal: A Guide for Instructors and Students

You could, of course, use any photographs you take yourself. To avoid rights issues, ask any human subjects included in your photos to sign a waiver giving you permission to use their likenesses. In the case of minors, you need to ask their guardians to sign the permission form.

Similarly, pictures taken by friends or relatives could be available as long as you get signed permission to use the photo as well as signed permission from any human subjects in the photo. Although it might seem silly to ask your sister, for example, to give you signed permission to use her photo or image, you never know what complications you could encounter later on. So, always protect yourself with permission.

A third option is to create your visuals. You do not have to be an artist to choose this option successfully. You can use computer programs to generate professional-looking charts, graphs, tables, flowcharts, and diagrams, or hire a graphic designer to do this for you.

Subject your visuals to the same level of scrutiny as your writing. Keep in mind that if you find one person has a problem with one of your visuals, there will be others who also take exception. On the other hand, remember that you can never please everyone, so you will have to use your judgement.

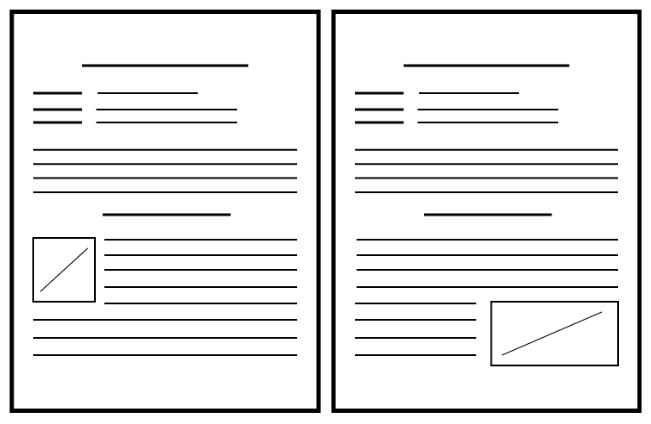

When you insert an image into your text, you must make some physical decisions.

Text Only Document by JR Dingwall

When you insert an image into your text, you must make some physical decisions.

Left and Right Justified Images in a Document by JR Dingwall

Another choice is to move the text down to create page-wide space for the image. In such situations, the image is typically placed above the related text. This format is usually used at the beginning of a document where the image treatment does not break up the text.

Full Justified Image in a Document by JR DIngwall

Incorporating charts, graphs, and other visuals is a way to break up blocks of text using visuals and white space. You can add white space by presenting lists vertically rather than running them horizontally across the page as part of a sentence. Also, leave enough white space around images to frame the images and separate them from the text.

Choose visuals to advance your argument rather than just to decorate your pages. Just as you would not include words that are fluff, you should not include meaningless images. Also, just as you aim to avoid the use of fallacies in your text, you also need to be careful not to use fallacious visuals. For example, if you were arguing for the proposition that big dogs make good pets for families, you might show a picture of a friendly-looking Rottweiler puppy. But if you were against families having big dogs for pets, you might choose an image of a mean-looking adult Rottweiler baring its teeth. Watch out for the use of visuals that sway your opinion in the material you read, and use objective images in your own work.

Thanks to programs such as Adobe Photoshop, you can easily alter a photo, but make sure to do so ethically. For example, say that you are making an argument that a company unfairly hires only young people and disposes of employees as they age. You decide to show a photo of some of the employees to make your point. You take a photo of the company’s employees (both old and young) and crop the original photo to show only the young employees. This cropping choice would be misleading and unethical.

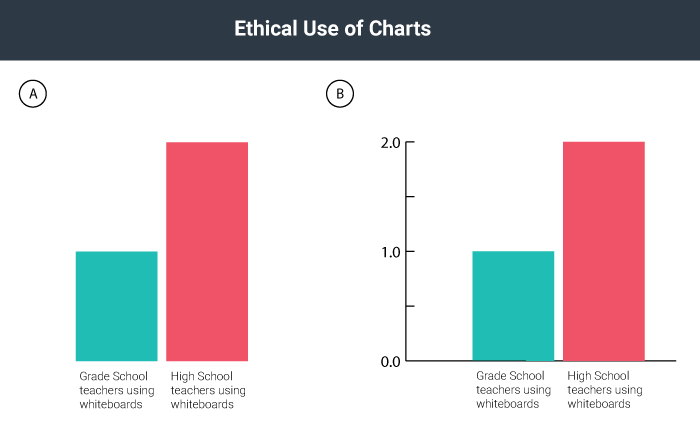

You have probably seen tables or graphs that convey something that is not exactly accurate. For example, the two graphs in the image below could be used as proof that “twice as many” high school teachers as grade school teachers choose to use computer-driven whiteboards. Graph A seems to support this statement nicely. If you look at Graph B, however, you realize that the entire sample includes only two teachers, so “twice as many” means, literally, two rather than one—an inadequate sample that leads to neither impressive nor convincing data. Be very careful not to misrepresent data using tables and graphs, whether knowingly or accidentally.

Ethical Use of Charts by L. Underwood

Visuals, like verbal or written text, can make ethical, logical, and emotional appeals. Two examples of ethical appeals are a respected logo and a photo of the author in professional dress. Graphs, charts, and tables are examples of logical appeals. For the most part, nearly all visuals, because they quickly catch a reader’s eye, operate on an emotional level—even those that are designed to make ethical and logical appeals.

Consider the following options when you choose visuals for your work:

In this chapter you have thought about the reasons to use a visual in your professional documents and have looked at different types of visuals, from diagrams and charts to illustrations and photographs. You have read about the purposes visuals serve and have learned that knowing whether your visual is intended to decorate, represent, analyze, or organize is key to choosing the right type of image.

You have also looked at ways to find and credit images, learning about Creative Commons licensing and exploring ways to fairly use others’ images in your work. You have also learned a little bit about positioning images within your documents and the uses (and abuses) of visual rhetoric.

When you are confident in your ability to use images in your work, move on to the next chapter.

Learning Highlights

An interactive or media element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/foundationsprofcomms/?p=1111

If you would like to read more about finding, using, and attributing Creative Commons–licensed materials, see the following sites:

Picardi, R. P. (2001). Skills of workplace communication: A handbook for T&D specialists and their organizations. Westport, Conn.: Quorum Books, 2001.