Ambachtscheer, K. P. (2016). The future of pension management: Integrating design, governance, and investing. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Ariely, D. (2018, February 13). Tricking yourself to save [Audio podcast]. BBC World Service. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/w3csw8d9

Baldwin, B. (2017). The pensions Canadians want: The results of a national survey. Report on a Survey Prepared for the Canadian Public Pension Leadership Council. Retrieved from: http://cpplc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/2017-034_cpplc-report_the-pensions-canadians-want_20170501.pdf

Blinch, M. (2018, May 1). Underfunded pensions: How to fight back. The Globe and Mail. Retrieved from https://beta.theglobeandmail.com/report-on-business/underfunded-pensions-how-to-fight-back/article4289586/?ref=http://www.theglobeandmail.com&

Bloom, P. (2015, July 27). People don’t actually want equality. The Atlantic Magazine. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2015/10/people-dont-actually-want-equality/411784/

Bossaerts, P. (2009). What decision neuroscience teaches us about financial decision making. Annual Review of Financial Economics, 1. 383-404. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.financial.102708.141514

Bosworth, B., Burtless, G., & Steuerle, E. (2000). Lifetime earnings patterns, the distributions of future social security benefits, and the impact of pension reform. Social Security Bulletin, 63(4), 74-98.

Bowles, H., & Gintis, H. (1998, December 1). Is Equality Passé? The Boston Globe. Retrieved from http://bostonreview.net/samuel-bowles-herbert-gintis-is-equality-passe

Brown, D. E. (1991). Human Universals. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

Buckholtz, J.W., & Marois, R. (2012). The roots of modern justice: Cognitive and neural foundations of social norms and their enforcement. Nature Neuroscience, 15(2012), 655-551. doi: 10.1038/nn.3087

Carter, R. M., Meyer, J. R. & Huettel, S. A. (2010). Functional neuroimaging of intertemporal choice models: A review. Journal of Neuroscience, Psychology, and Economics, 3(1), 27-45. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0018046

Collins, J. M. (2010). A review of financial advice models and the take-up of financial advice. Working Paper WP 10-5. Madison, WI: Centre for Financial Security, University of Wisconsin-Madison. Retrieved from https://centerforfinancialsecurity.files.wordpress.com/2011/02/2010-a-review-of-financial-advice-models-paper.pdf

Constitution Act, 1982. Justice Laws Website, Retrieved from http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/Const/page-15.html

Contract. (n.d.) Business Dictionary. Retrieved from http://www.businessdictionary.com/definition/contract.html

Corning, P. (2011). The Fair Society: The Science of Human Nature and the Pursuit of Social Justice. [Kindle Edition] Kindle Locations 1443-1444).

Corning, P. (2015). The Science of human nature. The Journal of Natural and Social Philosophy, 11(1), 15-40. Retrieved from https://www.cosmosandhistory.org/index.php/journal/article/view/466

D’Agostino, F., Gaus, G., & Thrasher, J. (2017). Contemporary approaches to the social contract. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved from https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2017/entries/contractarianism-contemporary/

Dawkins, R. (1976). The Selfish Gene. London, UK: Oxford University Press.

Dicken, T. (2013, August 2). Five ideas from “The Social Contract” that supports a socialist society. The Socialist. Retrieved from http://www.thesocialist.us/the-socialist-contract-five-ideas-from-of-the-social-contract-that-support-a-socialist-society/

Dixon, J., & Hyde, M. (2003). Public pension privatization: Neo-classical economics, decision risks and welfare ideology. International Journal of Social Economics, 30(5), 633-650. https://doi.org/10.1108/03068290310471899

EBRI (2016)

EBRI (2017)

Fehr, E. & Camerer, C. F. (2007). Social neuroeconomics: The neural circuitry of social preferences. Trends in Cognitive Science, 11(10), 419-427. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2007.09.002

Finke, M. S., Huston, S. J., & Winchester, D. D. (2011). Financial advice: Who pays. Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, 22(1), 18-26.

Fisher, I. (1930). The theory of interest, as determined by impatience to spend income and opportunity to invest it. New York, NY: Macmillan. Retrieved from http://files.libertyfund.org/files/1416/Fisher_0219.pdf

Fletcher, S. (2017, July 7). Citizen’s dialogue on Canada’s future: A 21st century social contract. [online dialogue] posted to https://participedia.net/en/cases/citizens-dialogue-canada-s-future-21st-century-social-contract-2

Friedman, M. (1957). A theory of the consumption function. New York, NY: Princeton University Press. Retrieved from http://www.nber.org/chapters/c4405.pdf

Government of Canada. (2017, April 11). Canada Pension Plan enhancement. Retrieved from https://www.canada.ca/en/services/benefits/publicpensions/cpp/cpp-enhancement.html

Government of Ontario. (2018, August 23). Guaranteed Annual Income System payments for seniors. Retrieved from https://www.ontario.ca/page/guaranteed-annual-income-system-payments-seniors

Gray, A. (2009). Rousseau’s form of socialism. Auburn, AL: Mises Institute. Retrieved from https://mises.org/library/rousseaus-form-socialism

Grech, A. G. (2017). Comparing state pension reforms in EU countries before and after 2008. Journal of International and Comparative Social Policy, 33(3), 225-239. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/21699763.2017.1363075

Greene, J. & Haidt, J. (2002). How (and where) does moral judgment work? Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 6(12), 517-523. Retrieved from http://faculty.virginia.edu/haidtlab/articles/greene.haidt.2002.moral-judgment.pub024.pdf

Griffith, M. F. (1997). John Locke’s influence on American government and public administration. Journal of Management History, 3(3), 224-237.

Hung, A., & Yoong, J. (2010). Asking for help: Survey and experimental evidence on financial advice and behavior change. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Working Paper Series WR-714-1.

Hyde, M., & Shand, R. (2017). Retirement, pensions and justice. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Krebs, J. R., & Davis, N. B. (1981). An introduction to behavioural ecology. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates Incorporated.

Li, M., & Tracer, David P. (2017). Interdisciplinary perspectives on fairness, equity, and justice. New York: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-58993-0

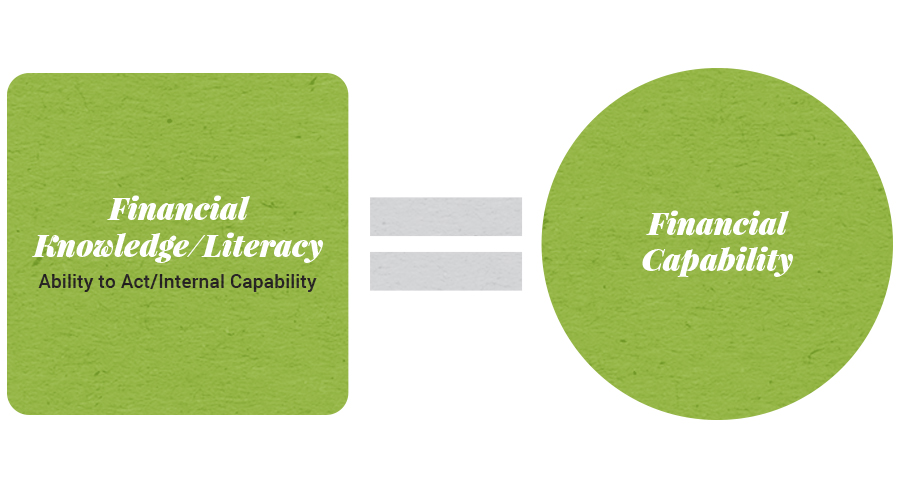

Lusardi, A. (2012, October 4). Financial literacy or financial capability? [blog post] Retrieved from

http://annalusardi.blogspot.com/2012/10/financial-literacy-or-financial.html

Macdonald, N. (2016, September 13). A very short list of Canadian values. CBC News. Retrieved from http://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/neil-macdonald-kellie-leitch-values-survey-1.3759075

Mason, G. (2018, January 19). The inexcusable treatment of Sears employees: A cautionary tale. The Globe and Mail. Retrieved from https://www.theglobeandmail.com/opinion/the-inexcusable-treatment-of-sears-employees-a-cautionary-tale/article37661479/

Mata, R., Pachur, T., von Helversen, B., Hertwig, R., Rieskamp, J., & Schooler, L. (2012). Ecological rationality: a framework for understanding and aiding the aging decision maker, Frontiers in Neuroscience, 6(19). doi: https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2012.00019

Mayers, A. (2014, August 17). Why there’s global urgency to enhance pensions: Mayers. The Toronto Star. Retrieved from https://www.thestar.com/business/personal_finance/retirement/2014/08/17/why_theres_global_urgency_to_enhance_pensions_mayers.html.

Meslin, E. M., Carroll, A. E., Schwartz, P. H., Kennedy, S. (2014). Is the social contract incompatible with the social safety net? Revisiting a key philosophical tradition. Journal of Civic Literacy, 1(1), 1-15.

Retrieved from https://journals.iupui.edu/index.php/civiclit/article/download/16668/17201.

Messacar, D. (2017, February 13). Economic Insights: Trends in RRSP Contributions and Pre-retirement Withdrawals, 2000 to 2013. Retrieved from https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/catalogue/11-626-X2016064

Miller, M, Reichelstein, J., Salas, C., Zia, B. (2014). Can You Help Someone Become Financially Capable? A Meta-Analysis of the Literature. Policy Research Working Paper No. 6745. World Bank, Washington, DC. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/16833

Mitchell, O. S., & Turner, J. (2010). Human capital risk and pension outcomes. In R. P. Hinz, P. Antolin, R. Heinz, J. Yermo (Eds.). Evaluating the financial performance of pension funds (pp. 119-151). Wash., DC: World Bank.

Modigliani, F. (1966). The Life Cycle Hypothesis of Saving, the Demand for Wealth and the Supply of Capital. Social Research, 33(2). 160-217.

Montizaan, R., Cörvers F., De Grip, A., & Dohmen, T. (2012). Negative reciprocity and retrenched pension rights. Retrieved from https://www.uni-kassel.de/fb07/fileadmin/datas/fb07/5-Institute/IVWL/Forschungskolloquium/SS12/Montizaan_paper_reciprocity_04-07-2012.pdf

Office of the Auditor General of Ontario (2016). Section 4.01 Accounting Treatment of Pension Funds. Annual Report 2016. Volume 1 (pp. 672-692). Toronto, ON: Queen’s Printer for Ontario. Retrieved from http://www.auditor.on.ca/en/content/annualreports/arreports/en16/2016AR_v1_en_web.pdf

Office of Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada (2015). Registered Pension Plans (RPP) and other types of savings plans – coverage in Canada. Retrieved from http://www.osfi-bsif.gc.ca/Eng/Docs/fs_rpp_2015.pdf

Punko, N. (2015). “Held to a Higher Standard” – Should Canada’s Financial Advisors Be Held to a Fiduciary Standard? Applied Project Final Proposal APRJ – 699. Retrieved from http://dtpr.lib.athabascau.ca/action/download.php?filename=mba-15/open/punkon-aprj-final.pdf

Rawolle, S. (2013). Understanding equity as an asset to national interest: Developing a social contract analysis of policy. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 34 (2), 231-244, https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2013.770249

Retraite Québec (n.d.) The retirement pension under the Québec Pension Plan. Retrieved from https://www.rrq.gouv.qc.ca/en/retraite/rrq/Pages/calcul_rente.aspx

Sandbrook, W., & Gosling, T. (2014). Pension reform in the United Kingdom: The unfolding NEST Story. Rotman International Journal of Pension Management, 7(1). Retrieved from https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2449791

Schillington, R. (2016). An Analysis of the Economic Circumstances of Canadian Seniors. Ottawa, ON: Broadbent Institute. Retrieved from http://www.broadbentinstitute.ca/an_analysis_of_the_economic_circumstances_of_canadian_seniors

Schwittay, A. (2014). Designing development: Humanitarian design in the financial inclusion assemblage. Political and Legal Anthropology Review, 37(1) 29-47. doi: 10.1111/plar.12049.

Shapira, Z. & Venza, I. (2001). Patterns of Behavior of Professionally Managed and Independent Investors. Journal of Banking & Finance, 25(8), 1573–1587.

Sherraden, M. S. (2013). Building blocks of financial capability. In J. Birkenmaier, M. S.

Sherraden, & J. Curley (Eds.), Financial capability and asset development: Research, education, policy, and practice (pp. 3–43). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Steeve, J. (2018, May 11). Benefits and pension for all: why Canada needs a new social contract. The Globe and Mail. Retrieved from https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/national/time-to-lead/benefits-and-pensions-for-all-why-canada-needs-a-new-social-contract/article15348751/

Stevens, J. R. (2010). Rational decision making in primates: The bounded and the ecological. In M. L. Platt & A. A. Ghanzafar (Eds.) Primate Neuroethology (pp 98-116). New York: Oxford University Press. Retrieved from http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/psychfacpub/531

Social Contract Theory. (n.d.) Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved from http://www.iep.utm.edu/soc-cont/ .

Statistics Canada (2017, November 29). Labour in Canada: Key results from the 2016 Census. Retrieved from https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/171129/dq171129b-eng.htm.

Steeve, J. (2018, May 11). Benefits and pension for all: Why Canada needs a new social contract. Toronto Globe and Mail. Retrieved from https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/national/time-to-lead/benefits-and-pensions-for-all-why-canada-needs-a-new-social-contract/article15348751/

Thaler, R. H., & Sunstein, C. R. (2008). Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

The Law Handbook. (2018). What is a contract? Retrieved from http://www.lawhandbook.org.au/2018_07_01_01_what_is_a_contract/ .

Vallier, K. (2011, January 17). OPR, CH.I.1: Social morality. [blog post]. Retrieved from http://publicreason.net/2011/01/17/opr-chi1-social-morality/

Wambi, I. (2015). The relevance of Thomas Hobbes’ theory of social contract to the modern world, Retrieved from https://www.academia.edu/10987040/Relevance_of_the_Social_Contract_Theory_to_the_Modern_World?auto=download

Wartzman, R. (2017). The end of loyalty: The rise and fall of good jobs in America. NY, NY: PublicAffairs.

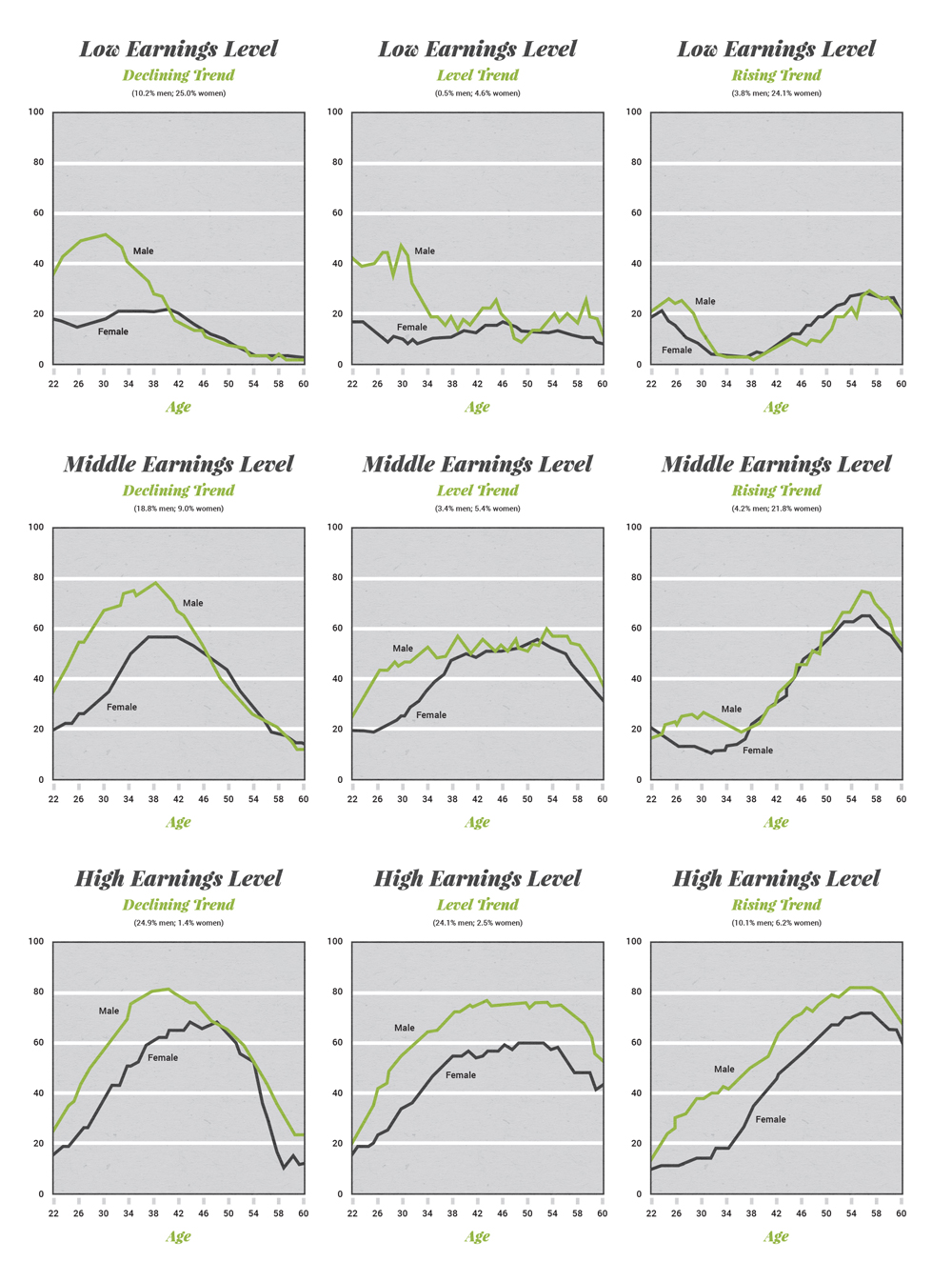

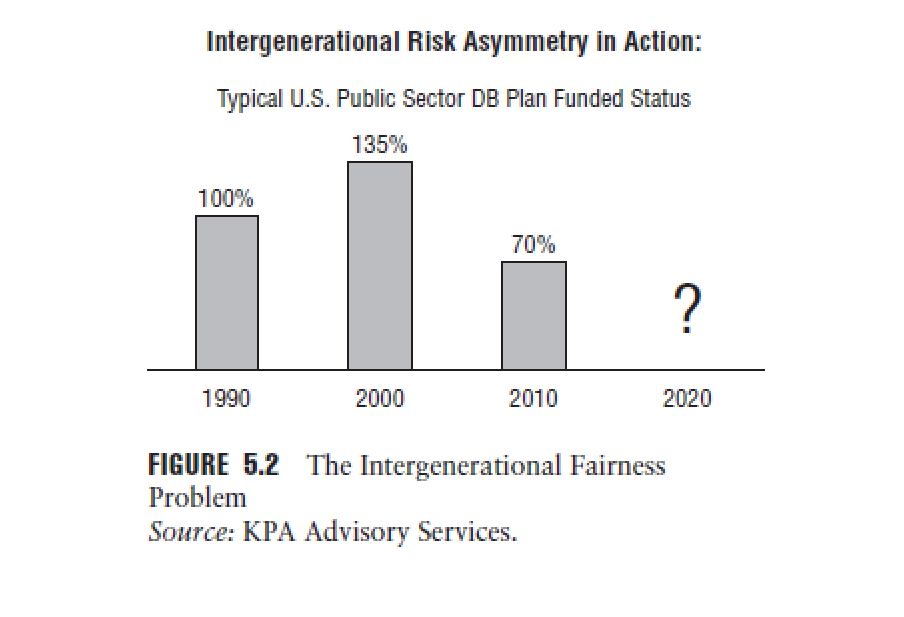

Figure 8. The Intergenerational Fairness Problems

Figure 8. The Intergenerational Fairness Problems

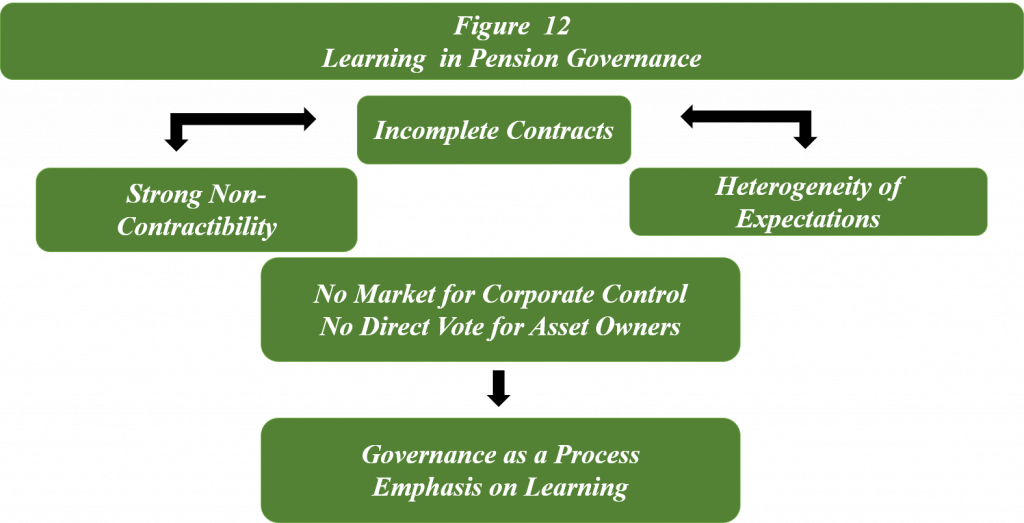

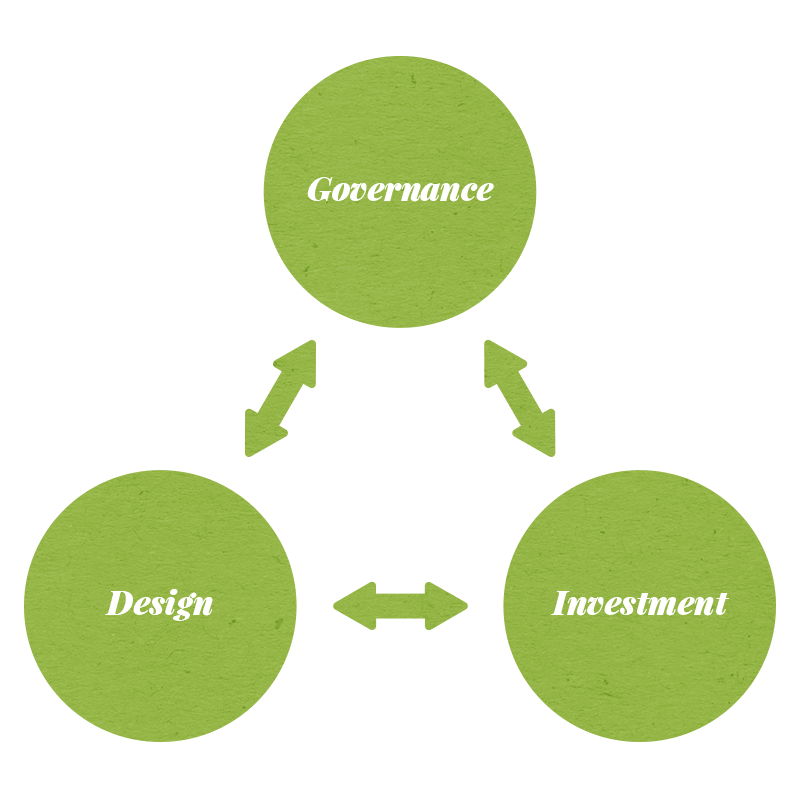

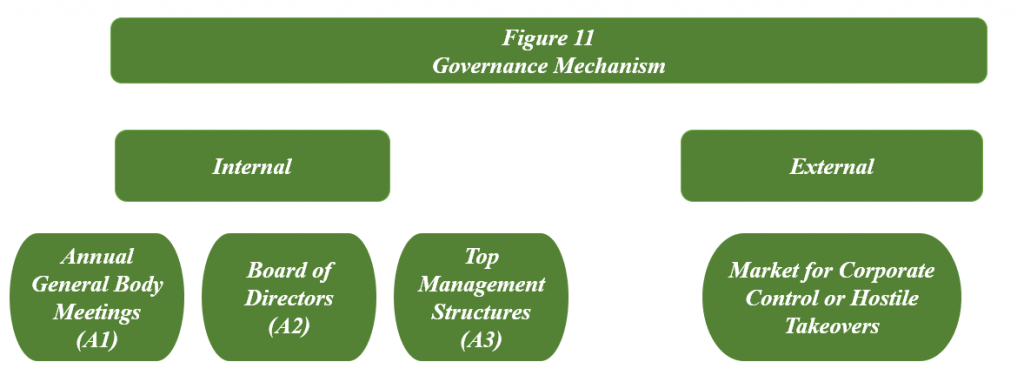

Figure 11. Governance Mechanism

Figure 11. Governance Mechanism