Student-Centered Learning: Subversive Teachers and Standardized Worlds by McMaster University is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Student-Centered Learning: Subversive Teachers and Standardized Worlds by McMaster University is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

P.K. Rangachari/Stacey Ritz

“When you set out for Ithaka ask that your way be long/Full of adventure, full of instruction.” So begins C.P. Cavafy’s oft-quoted poem, Ithaka. Though the metaphor of a journey has often been used for a student’s passage through an educational system, it applies equally well to their teachers. Promises and perils dot their way. Student-centered learning is often touted as a panacea for educational ills but can quickly slide into self-indulgence. So, teachers need to steer carefully through the twin Scylla of standardised tests and the Charybdis of self-indulgent learning.

This collection is a tribute to Delsworth Harnish, a master navigator through the treacherous waters of academia. He knew all the rules and broke them with impunity. He set up programmes that fostered self-directed learning and was quite averse to standardised testing, which he felt stifled true learning. He had a particular fondness for Postman and Weingartner’s Teaching as a Subversive Activity. When we decided to gather together essays to honour his memory, we asked contributors to consider several themes. These included the possibilities of promoting student-centred learning in a standard-based world, dimensions of subversive teaching in our troubled times, and the subtler notion of justice.

We asked contributors to think about these issues and write about them in a personal way. We wanted the essays to capture Del’s interests but be true to his spirit as well. He was quirky, often elliptic and impatient with the pedantic formal. We gave licence to the contributors to write about these themes in any way they chose. We wanted an unprescribed collection, even to the point of having no set pattern for the references, in case authors chose to use them.

Bacon felt that “Some books are to be tasted, others to be swallowed, and some few to be chewed and digested.” What readers make of this collection is up to them. We wanted this book to be browser-friendly. The essays in this book have no set style—many are riffs on the themes we have mentioned, others take on a more formal hue. If it all adds up to a patchwork quilt, so be it. Del Harnish would have liked it that way.

A sincere thanks to Dr. Stacey Ritz for continuing support and encouragement, Joanne Kehoe for all her help in making the collection coherent and readable, Chris Lombardo for his inspiring cover design, and the Canadian tax-payers who support publicly-funded Universities such as McMaster University.

John Kelton

For a long time, Del Harnish worked down the hall from me, but we barely knew each other. He did his work in virology. I did mine in haematology. We crossed paths, but oddly, none of our interactions stuck in my memory. Then I met the real Del, the shadowy secret agent, and he would be a vivid character in my life for the duration of our friendship.

I was walking across campus one night. It was dark and still, with a thick fog resting heavily on the ground. Coming up to MUMC I could see someone at the back of the medical centre. He was leaning at an angle against the building, one leg bent back against the wall. He was smoking a sinister-looking black cigarette. As I approached, this mysterious figure took a long drag, tilted his head back and blew the smoke up to feed the fog.

He looked like a character from a black-and-white Bergman movie—a spy, a cat burglar, an agent provocateur!

“Del,” I said, “is that you?”

“Yes,” he replied.

“What are you doing?”

“Thinking,” he said. I was soon to learn that when Del was thinking—which was almost always—amazing things would inevitably follow. In fact, for the next 30 years, I watched Del embrace the role of covert operative and agent provocateur based largely on the power of his thinking. He may have started in virology, but he found his calling in education. He set aside the linear discipline of basic research and moved into a field and a role where his devilish imagination would not be constrained. He always carried with him valuable lessons learned in the lab—the power of a well-framed question, for example—but a figure who could look that cool smoking in the fog was destined for something different than the grind of laboratory work.

Predictably, every time I retold the story of that fateful, foggy encounter, Del would belt out his wonderful laugh. I was never sure if he was laughing at the circumstances of the meeting, at his own image, or at the obvious delight I took in telling the tale.

Around the dawn of the new millennium, our Faculty was looking for someone to lead a novel program called the Bachelor of Health Sciences. With some hesitation, Del took the position and quickly displayed his immense capacity for disruptive and constructive innovation. As the program’s founding assistant dean from 2000 to 2015, he excelled as an educator and champion of inquiry-based, student-centred pedagogy. His vision and character defined the program’s trail-blazing reputation and helped make it the most sought-after undergraduate program in the country.

If ever there was the perfect job for a person who tolerated university rules while dedicating himself to anarchy, it was Del’s job. He would often remark that education should be a full-contact sport. He was a man who loved the scuffling and high sticking in the corners around the pedagogical goal.

Del had a prodigious mind and a formidable memory for the most microscopic and tedious rules and regulations … provided they supported his argument of the day. And when it would be brought to his attention that there was an opposing perspective on the same guidelines, he would give his half smile and simply say, “Well, that’s one interpretation.” One of Del’s several subversive mottos was, “Don’t bend the rules. Break them.” He would often begin his morning with the question, “What kind of trouble can I cause today?” He would just as often end the afternoon by declaring, “The rest of the day is cancelled, due to a lack of interest on my part.”

As the BHSc program evolved into national prominence, Maclean’s magazine declared it to be the finest undergraduate program in Canada and Del soon arrived in my office full of pride, pointing to the article. He said, “You know what’s best about this? Every student arrives wanting to go to medical school and by the time I’m done with them, most realize there are better things to do with their lives.”

His leadership style was ambitious and idealistic, inspiring many. As the vice-dean of undergraduate health sciences education from 2015 to 2018, he was a visionary leader in launching collaborative cross-Faculty programs. Yet, as his influence, profile, and impact expanded, he maintained a delightful inability to suffer fools gladly, and I learned emphatically that I was a frequent inductee into his gallery of dunces. However, the curmudgeon in Del was always quickly overrun by the obvious joy he derived from the colleagues and students who were drawn to him like steel filings to a magnet. It was even more obvious that he adored his wife Liz and children Shaundra and Lauren. Outside of work, you never saw Del without Liz, unless he was at Home Depot.

Del Harnish was one of our country’s most decorated educators. He earned several McMaster and national awards for curriculum development and was a 3M Teaching Fellow, Canada’s highest award for university pedagogy. Yet, these resumé virtues describe Del the same way the word “orange” describes a sunset. Del wasn’t a biography, he was an experience. He was qualitative … and the essence of that quality was that he is irreplaceable.

There are things in life we can read and hear about, but we cannot truly understand until we experience them ourselves. Not coincidentally, these are the most encompassing, confounding, and transforming experiences—things like falling in love, becoming a parent, discovering something revolutionary. With these experiences, we never truly understand until they happen … and Del was a happening.

For someone who loudly professed his love of all things “messy,” Del’s office was surprisingly neat and tidy. I was confused by this juxtaposition until I realized that the order in his office allowed visitors to notice the important things. To me, the most important was a simply hung photograph of our dear friend Del surrounded by his beloved, inspired and inspiring students.

That is the Del Harnish I remember and celebrate.

Harold B. White, III

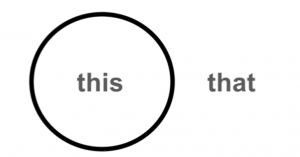

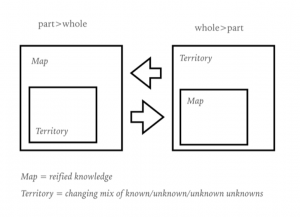

H2O is not water. For that matter, neither is “water”. These coupled, seemingly nonsensical statements that I had written on the board before class perplexed a large majority of my biochemistry students. Discussion among students of the meaning of the statements introduced them to the unfamiliar pedagogy of Problem-Based Learning. They were about to encounter this new way of learning after years of experience with traditional, information-dense, stand-and-deliver science courses to which they had become

comfortable. While the symbolic chemical formula, H2O, conveys information of importance to a chemist, there is much more to the substance we call water, and personal experience influences individual perceptions. As Korzybski emphasized, “the word is not the thing.” Consider the differing perceptions of “water” by a biochemist, an environmental engineer, a meteorologist, a sailor, a farmer, a limnologist, a sanitation worker, an architect, a swimmer, a parent, a politician, an Inuit, or a Bedouin? A more nuanced understanding of “water” develops with experience, discussion, and exposure to different perspectives. Likewise, learning biochemistry or any other subject involves learning and communicating in the language of the discipline. We construct meaning, and that influences how we think, work, and behave.

Our individual perceptions of “education” vary even more widely than our perceptions of “water”, which, at least, is a recognizable substance. What constitutes “good” or “bad” education depends on the goals, methods, and experiences of the perceiver. Half a century ago, in the midst of the social unrest accompanying the Vietnam War, Neil Postman and Charles Weingartner’s perception of education resulted in their scathing criticism of education as practiced in the United States at the time, as outlined in their book Teaching as a Subversive Activity. They advocated student-centred pedagogy in which learning emerged from students engaging problems relevant to them and society. Students would learn how to learn through the process of asking questions and pursuing relevant knowledge, independent of particular disciplines or assertions by authority figures. This would prepare them for decision making in a rapidly changing world in which the future could not be anticipated.

Education exposes students to new objects, processes, concepts, and ideas that all have words associated with them and, in turn, expand the realm of thought. Knowing goes beyond simple definitions. To think and participate in any discipline requires knowledge and use of its language. Providing definitions to memorize, like “a colorless, transparent, odorless liquid that is the basis for the fluids of living organisms,” is insufficient. Students must use words in context and internalize the nuanced meanings associated with them in order to communicate effectively with others who also have similar (but not necessarily identical) understanding. “Student-centred education” means different things to different people, but it shifts the focus from “teacher-centred education” to learning rather than telling.

Knowledgeable, independent thinkers threaten the status quo. They challenge the politics of their parents, question the beliefs of their religious leaders, evaluate the qualifications of candidates, expose unfair practices, disregard most advertising, and are willing and open to consider alternatives. Little wonder that those in positions of power are suspicious of and wish to silence minds that question. According to Postman & Weingartner (1969), the purpose of education should be to create an environment that cultivates independent thinkers. Such goals were radical 50 years ago and are still radical in many quarters today. However, numerous teachers now practice constructivist, student-centred pedagogy that aligns with much of the “subversive” agenda.

One of many quotable quotes in Teaching as a Subversive Activity is “…once you have learned how to ask questions—relevant and appropriate and substantial questions—you have learned how to learn and no one can keep you from learning whatever you want or need to know.” Regardless of the discipline, the curriculum should have this single goal. As expressed by Postman & Weingartner (1969), every course should expect students to liberate their curiosity, ask substantive questions, and develop refined “crap detectors.”

Imagine a course in which the instructor places a glass of water in front of the students and asks them to generate 100 questions, evaluate the substance and quality of those questions, and use them to guide a semester of study? I think that Del Harnish would be excited about such a course.

References

Postman, N. & Weingartner. (1969). Teaching as a Subversive Activity. New York, NY: Delta Publishing Co., Inc.

David Harris

I confess that I did not know Dr. Del Harnish, but I have gained an understanding of him from the written words and respect of his colleagues. Dr. Harnish was a true believer in student-centred learning, and he lived it through his work in the BHSc program at McMaster. In the commentaries, it is clear that Dr. Harnish aimed to prepare his students for the uncertainty, troubles, and opportunities that were so aptly outlined in Teaching as a Subversive Activity, written almost 50 years ago (Postman & Weingartner, 1969). This led me to ask myself, “are we in medical education doing enough to prepare future physicians for the uncertainty they will face in the future?”

Although the field of medicine seems to be fully alive with uncertainty, I was blind to this concept for many of my first years teaching physiology at a medical school. My first interaction with this concept (although I did not recognize it at the time) took place in the classroom when I observed a very successful nephrologist and hypertension specialist respond “I don’t know” to a student question. Up until that moment, I don’t believe that I had seen any faculty member make such a statement in front of medical students—at the time, most of us viewed this type of uncertainty as chum in the water for an upcoming feeding frenzy. Despite my presumptions, the circling sharks did not appear. Although I would not have termed it “uncertainty” at the time, I learned as a junior faculty member that it was okay to say “I don’t know”.

My first formal introduction to the world of uncertainty took place at a conference where Dr. Andrew Olsen spoke about the topic. In his presentation, he spoke about a young female patient who had right upper quadrant pain. Her parents took her to several physicians and the running diagnosis of a gallstone was considered. Ultrasounds were ordered to confirm the presence of stones, but no stones were visible. All other symptoms were supportive of this diagnosis, and the surgeons pushed ahead despite emptiness in the gall bladder; they were certain she needed surgery. During the surgery, the patient had a severe hemorrhage that the surgeons could not control, and she died. She was less than 18 years of age. As a new father of two young girls, this story hit home. This death resulted from the inability to say “I don’t know what is wrong” and the inability to recognize when one must slow down in clinical decision making. As patients, we hope that our doctor or our child’s doctor is confident. However, confidence can be tenuous in in the face of uncertainty.

The challenge is how to teach our medical students to realize the uncertainties that percolate through medicine on a daily basis. I teach early in the medical school curriculum, before any patient care exposure and where diseases are presented in a virtual case on a computer monitor. Most of our curriculum is still focused on content delivery rather than developing thought processes. The primary method of assessment at my school, and many others, is the United States Medical Licensing Exam-like multiple choice question; this prepares students for Step 1 of the exam, which is one of the most influential determinants of their residency application. At least one major issue arises from this approach—this exam tests only one domain, knowledge. There is little uncertainty because the answer is either wrong or right. Where, then, do students learn about other important domains such as critical thinking or problem solving? In the current medical school environment where we feel as though we must cover every disease for the student, I would argue that the answer lies in finding alternative ways to promote student-centred learning.

A quote from a colleague of mine, an educational psychologist, has served as my foundation for teaching. She states simply that “if you as a faculty are working harder in the classroom than your students, they are probably not learning.” (Note, this does not include the preparation work done behind the scenes!). My feeling is that lecture is by far the most common pedagogy occurring in medical schools today. The standard lecture (faculty-centred) is the extreme example of the faculty doing the majority of work. Students are not testing their mental models of a process or struggling with a concept. As stated earlier, faculty tend to retreat to this method, driven by the need to provide content and the perception that the standard lecture is the most efficient way to do this. The ever-expanding content in the field of medicine also severely limits the opportunities for student-centred learning and any ability to introduce uncertainty.

So, how do we transition to student-centred learning in medical education? Interestingly, I believe that faculty will be forced to transition if they haven’t already. Not by Deans, accrediting bodies, or other administration, but by the numerous resources that are quickly becoming available for students. Currently, there are numerous companies that are able to deliver content in presentations that are high quality, efficient (student can view in 2x mode), and provide recall or USMLE-like questions relevant to the content. Many faculty feel threatened, viewing these resources as their “replacement”. I feel that these external resources will actually allow faculty more time to focus on higher order thinking (what educator doesn’t desire this?) or clinical reasoning. These resources should also provide faculty time to highlight their experience and show the true uncertainties that their job deals with on an everyday basis. Activities should be developed that have more than one right answer. Let students realize that most choices we make in our lives and careers do not always have “right” answers.

Ultimately, we need to realize that faculty are not the “gate keepers” of knowledge as they were in the past. Medical educators must shift the responsibility of learning to the learner. To do this, we must have confidence that the students will be able to “get” something without us feeling the need to tell them everything. Let students use more efficient content delivery methods to buy them time. This frees time for faculty to share our greatest asset, experience. Who knows? This just might give students the time to explore new, improved methods for optimizing patient care, which should be a goal for all.

References

Postman, N. & Weingartner. (1969). Teaching as a Subversive Activity. New York, NY: Delta Publishing Co., Inc.

Joshua Koenig and Ashley Marshall

“There have been plenty of days when I have spent the working hours with scientists and then gone off at night with some literary colleagues. I mean that literally. I have had, of course, intimate friends among both scientists and writers. It was through living among these groups and much more, I think, through moving regularly from one to the other and back again that I got occupied with the problem of what, long before I put it on paper, I christened to myself as the ‘two cultures’. For constantly I felt I was moving among two groups—comparable in intelligence, identical in race, not grossly different in social origin, earning about the same incomes, who had almost ceased to communicate at all, who in intellectual, moral and psychological climate had so little in common…”. C.P. Snow, The Two Cultures, 1959 [1]

Authors’ Positionality

Joshua Koenig is a doctoral candidate studying at the McMaster Immunology Research Centre. He instructs courses in the Bachelor of Health Sciences program including: Introductory Immunology, Cell Biology, and Child Health. Josh sees the enduring fjord between science and the humanities and aspires to embody what C.P. Snow described as the bridge between “two cultures.” Josh’s expertise comes from his experience as a student and educator at an Ontario university.

Ashley Marshall is a professor of communications at Durham College, who obtained both a B.A. and M.A. from McMaster University. With the mentorship of Henry Giroux, Ashley’s research is rooted in public intellectualism and public pedagogy. Ashley’s humanities expertise widens the conversation about student-centric learning by conceptualizing intersectionality, neoliberalism, and equity. Ashley’s analysis comes from her position as a faculty member in the Ontario community college system.

Can one truly promote student-centred learning in a standards-based world?

No.

In this essay, we will define what we call student-centred learning, some of the key standards used to evaluate education, and who benefits from them. Lastly, we will explore how education perpetuates the standards-based world and discuss the potential that true student-centred education has moving forward.

In 1993, Alison King, then associate professor of education in the College of Education at California State University in San Marcos, gave a polemical review of where the focus should lie in teaching and learning, claiming that instructors should be less of a “sage on the stage” and more of a “guide on the side [2].” Since then, this conversation about the role of the instructor has continued and been reframed. Student-centred learning is the opposite of “teacher-centred learning,” where the instructor is the “sage on the stage” who harbours information and is entrusted to disseminate their wisdom to a (usually large) classroom of students. In contrast, student-centred approaches shift the focus of education from the instructor to the students. In student-centred models, instructors are viewed as facilitators who encourage and empower students to gain skills in self-directed and peer-to-peer learning. Student-centred approaches value hard and soft skill development and allow students to pursue their interests (not the instructor’s), and generally oppose learning to strict curricula or standardized evaluation criteria—adaptations of the Socratic teaching method. The 20th century ushered in pedagogical theorists who sought to re-integrate the Socratic method into the educational system and laid the foundation for what we know as constructivism, or specifically, “student-centred learning.” This movement had many forerunners (bell hooks, Maria Montessori, Paulo Freire, Neil Postman, John Dewey, etc.), and was primarily inspired by a need to assuage power imbalances, autocracy, and oppression within the learning environment. So, when attempting to define student-centred learning, we must also acknowledge an important tenant of its origin: these forerunners prioritized injection of democracy, equality, and subjectivity—inherently radical social objectives. Therefore, it is pertinent to label student-centred learning as borne from social justice.

Please note, we use standards and metrics synonymously throughout the text below.

Institutional Metrics

In April 2019, the incumbent Ontario government handed down their expectations for Ontario higher education funding. According to The Globe and Mail, “Ontario’s new performance-based funding model for colleges and universities will focus on 10 metrics that include employment and graduation rates, the amount of research and industry funding the institutions receive and the demonstrated skills of their students [3].” These metrics are loosely defined and still quite young—their impact in the classroom is yet to be seen—and therefore they will not be a focus of critique here. However, what we can glean from this change to higher education metrics is the ideology which led to their introduction: according to Minister Merrilee Fullerton, there is a “need to have performance-based funding and outcomes funding in order to keep the economy going the way it needs to go, allowing students to find jobs2.” This “outcomes” deliverable is what makes the college system attractive to some students and to some employers: there is an applied learning and a hands-on methodology that aids students who learn best this way. Meanwhile, the university system is often characterized as being “too theoretical,” or “too abstract” for the “real world,” which is echoed in the ideology behind these changes to funding.

As educators, which we would define as lifelong students, supporting the economy and ushering students toward finding jobs is a gross devaluation of higher education. For education to come even remotely close to being student-centred, the endgame cannot be employment, or employment alone. If education that “keep[s] the economy going the way it needs to go” is needed, then as a society we must also realize, explicitly, that we are workers first and people second. Is such a Manichean [4] divide even possible? Because we are analyzing “metrics,” the humanity of the students drops out of the equation: they are regarded as tuition dollars first, instead of curious, passionate, embodied people with real experiences and with material engagement with economic structures such as capitalism, racism, precarity, poverty, disability, and myriad oppression. So, with that, we assert that students are also people. We assert that Ontario’s “performance-based” metrics do not account for the human-aspects of the student experience.

Looking at the equation more closely, we realize that under today’s market logics, at the level of the institution, profit margins are the main tool used to evaluate educational programs. At the university level, students pay tuition, tuition goes to administration, administration pays the instructors, instructors teach the students. Sage-on-the-stage education delivered to large classes is, therefore, financially valuable to the institution (and prioritized above humanism, dialogue, intellectualism, or social transgression). The instructor salary for a single course can accumulate profit through many hundreds of heads of tuition dollars. In contrast, student-centred education is typically delivered in small classes and therefore is a less viable educational structure from a profit perspective. Charting a student’s progression takes time and energy from instructors. Establishing goals with students and evaluating their progress requires one-on-one time with students that is not possible as class sizes grow. Evaluations are typically not as simple as massified multiple choice questionnaires—creativity and curricular development are required. Constant re-evaluation of courses to match students’ needs requires dedication and legwork. All these activities require time and are therefore expensive, and again, deprioritized. Efforts to massify student-centred learning are presently a focus of educational research but, ultimately, most of these efforts fail. From our view, this failure occurs because student-centred learning is not meant to be massified. By this metric, student-centred education fails the standards-based world.

There is a complicated argument to be made: sage-on-the-stage education can produce profits that can be used to offer other very important social services to students, like hiring support workers for mental health services, hiring academic advisors to guide students, or even to support smaller student-centred programs that may not be as lucrative on their own. Further, in Canada, profits are used to hire scientists who generate societally valuable research. Nonetheless, the institutional and government metrics applied to education today are capitalist metrics that are used as an argument to provide a lower quality of education and to dissuade students from pursuing interests that motivate them in favour of those perceived to be economically beneficial.

Individual Metrics

The standards that students strive for are generally 1) grades, 2) a degree/diploma, and 3) employment. Grades are utilized as a “sorting” mechanism, in which an employer, scholarship granting agency, professional school, etc. can presumably judge the value of a person (or as some would impassively put it, the “quality of a candidate”) based on their grade scores. To this day, grades are used as a “realistic” metric for student success. And yet, grades are a relatively poor predictor of job success [5]. Our own institutions, which utilize grade-based evaluation, mistrust the output of grades from high schools and are reported to assign multipliers to “correct” student grades to ensure students from schools are “equally competitive” for acceptance to their premier programs [6], which raises the question: why do we think this is a valuable metric at all?

A lesser discussed issue is the social side of grading. From various perspectives, the education system perpetuates oppression against many demographics. For example, a prevalent notion remains that students who experience disability are not meant for the university environment. We have heard stories like the following, told numerous different ways and many times over: a colleague of ours likened a student with disabilities to a short basketball player. From their view, a short basketball player stands no chance of making it to the NBA. This colleague’s worldview dictates that some people are born for basketball, others are not, and that is how it should be. Students with alternative learning needs, in this analogy, should not have equal access to education—something that is their legal right in Canada (see AODA [7]).

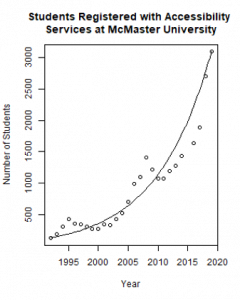

Contrary to our colleagues’ assertions, short players continue to have integral roles in the NBA. Muggsy Bogues, Isaiah Thomas, Kyle Lowry—all players well below the league average of 6’7’’ and often considered “too short for basketball”—have had stellar careers in the NBA. They have succeeded in spite of their “limitation,” for example, through their ability to shoot the ball and set up plays. Further, they succeed because of being short through the additional benefits of being quick, agile, and able to move in ways that their taller peers cannot. Similarly, students with disabilities are present and, in fact, many excel in higher education. These students have found ways to succeed despite their disabilities, and sometimes despite lapses and barriers in institutional support. However, the institution has done little, if anything, to consider the added value these students have because of their disability; students with disabilities offer unique perspectives and desirable skill sets that should be represented in academia and professional spheres. Present models of evaluation are not equipped to deal with this nuance, especially considering that for many instructors, we are still at the stage of othering marginalized perspectives as “unfit for the institution.” Addressing these concerns is increasingly pressing as the number of students with alternative needs is increasing at an exponential rate in higher education (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Number of students registered with McMaster University’s Student Accessibility Services over time. These data could have many explanations including: increasing support for students with alternative needs in high school, increased awareness for diagnosis, or potential increases in mental health disorders. Data collated from Ministry Reports [Available at: https://sas.mcmaster.ca/ministry-reports/].

A very similar story could be told about people of colour, queer folk, members of minority religions, women-identified individuals, and low-income populations, all of whom are still subject to systemic oppression that limit their engagement in higher education. As an example, the class of medical students accepted in 2016 at the University of Toronto had only one Black student in a class of 259 (0.4%) despite nearly 9% of Torontonians self-identifying as Black [8]. These are oppressed communities who have useful skill sets and experiences but live an existence outside of what the institution is designed for, who need accommodation, and yet must compete for the same metric: grades. Despite the adversity that these individuals face, the A+ they receive is valued as equal to any other A+, context largely ignored. Conventional wisdom dictates that students who do not achieve high grades are not as intelligent as their peers and are not as deserving of scholarships, coveted co-operative education placements, nor jobs. But we assert, through our experience, that the students who achieve an A+ are not always smarter, more deserving, more dedicated, or better members of society. Those who have a privileged place in society, those who don’t need to work while being in school, aren’t at risk of sexual abuse, who can move freely without discrimination, who do not have to dedicate significant mental faculties to their social position, are oriented to excel in higher education. They achieve high grades, and continue their social ascent, having already started with an advantage. Grades, as a metric, do not work for everyone. Grades fail hard-working students.

As educators we have relegated experiences to a “personal” sphere, which is expected to remain compartmentalized and distant from “learning.” This model ignores the thoughts, emotions, experiences, traumas, and successes of the student—the very essence of what engages them in humanity. Rejecting this model, forerunners of student-centred education have argued that the individual as a whole, not just as a student, should be at the centre of their (life-long) educational experience. This is where student-centred education fails, again, in a world of fetishized metrics. How do we reasonably evaluate a student’s experiences? What is an A+ in working through trauma? What grade do we give someone when they incorporate new content into their existence? What is the grade value of developing a new, intangible skill such as compassion? We advocate for broader conversations about “alternative assessments,” with the hope that these nuanced and intersectional approaches, which are largely rooted in Indigenous practices, become more mainstream and more respected. Instead of “alternative,” our ambition is that collaborative evaluation, discussion circles, inquiry (asking questions perhaps without finding answers), recognizing “traditional knowledge keepers” (Elders) as experts, and other forms of authentic assessment become part of faculty development.

In summary, we have discussed how standards/metrics are systematically valued, and then used to evaluate both educational programs and their students. We have also pointed out, from a theoretical and social perspective, how these metrics continue to fail students. We think, therefore, that the question should shift from “can we promote student-centred learning in a standards-based world?” to “what are we presently doing to promote the standards-based world?” and “how might a revolution of values impact institutions?”

Marshall MacLuhen famously wrote “the medium is the message” to explain how the “character” of a medium can have a greater impact on the individual than the content conveyed through the medium [9]. While MacLuhen applied this primarily to post-modernism and its media, such as newspapers, radio, and television, Postman and Weingartner expanded the theory to include the classroom as a medium. They deduced “…that the critical content of any learning experience is the method or process through which the learning occurs [10].” When we consider the current process of higher education, it is quite clear how standards remain at the forefront of society. No matter what educators tell students about taking their classes seriously, getting out what they put in, and encouraging students towards deep, interest-based learning, the output of most (if not all) higher education programs is some form of metric: institutional profit, employability, grades, and diplomas/degrees. The process of learning is largely ignored, students are expected to be proficient in the same material, to demonstrate that they can regurgitate that material, but with no real follow up that they have truly learned that material. The system, especially in teacher-centred education, tells these individuals to maximize effort on achieving standards and minimize effort into any other aspect, especially in actually “doing work.” The institution outlines the rules of engagement, the terms of success, and the conditions of a student’s exit. The students have minimal (if any) say in these matters.

Our institutions host students during important, formative years in their intellectual development and, even in the most student-centred of programs, instil in them a confining ruleset. The medium has told them that their agency for change is low and that conformity is ideal. These students, alienated [11], relegate into the periphery any need to critique everyday life and renew humanity with critical thought. They become absorbed into a system which dictates what is acceptable; a machine, from the outset, governed by standards. Standards become normalized, even expected. These same students go out into the world, vote, perpetuate the importance of “employability” and “performance-based funding,” without critically evaluating who wins in these systems and who continues to be left out (or, in more blunt terms, oppressed). They become the citizenry incapable of seeing themselves as either part of a larger problem or having the potential to be a part of a solution. After all, they are workers, not people. Our educational institutions are a fundamental reason that the standards-based world exists.

To challenge the “standards-based world” requires a revolution in values, difficult critical thought, and dialogue at the level of the institutions who, as they have historically done, should guide the intellectual revolution. The academy—every faculty member, every staff member, administrator, teaching assistant, and student—are members of society. If these individuals continue to believe that the present standards are static, that there is no alternative, then it will continue to be so.

As we have argued, this metrics-based world actively excludes, devalues, and hinders its populace and therefore must be changed. The answer, we propose, is a shift in the medium. By engaging in student-centred, non-compartmentalized, feeling, thinking, experiencing education, we are telling students, through the medium, that they are not simply workers but instead are individuals whose experiences are valuable. It tells individuals that they are an integral part of society who can enact change, and that a part of that change can be to shift value away from broken metrics. As Henri Lefebvre has said, “Our age is, in especial degree, the age of criticism, and to criticism everything must submit. Religion through its sanctity, and law-giving through its majesty, may seek to exempt themselves from it. But they then awaken suspicion, and cannot claim the sincere respect which reason accords only to that which has been able to sustain the test of free and open examination [12].” The free and open examination that Lefebvre seeks of institutions which hold influence is the same free and open examination we desire both of and in academies of higher learning. A belief in the status quo is a powerful mysticism that allows for these metrics and standards to remain inert. However, it is through Othered knowledge that the academy is becoming increasingly critiqued, and it is from the labour of these marginalized students and their allies that a reform of what students learn, and how they learn it, is on the horizon.

We will reiterate the first word of this essay: No, true student-centred learning cannot exist in a standards-based world. This is by design; it was never meant to. We propose this world is not desirable and suggest the use of student-centred learning as a radical tool to promote a shift in values towards dismantling the standards-based world.

AM would like to acknowledge Russell Means, who taught her that “Marxism is as alien to [her] culture as capitalism” too, and showed her how to be an ally to the Indigenous peoples. In honour of Means’s memory and in observance of Othered knowledges and what we can learn from them, what we can teach, AM champions Black oral traditions while also echoing Means: “…I detest writing. The process itself epitomizes the European concept of ‘legitimate’ thinking; what is written has an importance that is denied the spoken. My culture, the Lakota culture, has an oral tradition, so I ordinarily reject writing. It is one of the white world’s ways of destroying the cultures of non-European peoples, the imposing of an abstraction over the spoken relationship of a people.” AM also thanks her tireless team, The Rhizome Project: Kristen Shaw, Julia Theberge, Natasha Kowalskyj, Kevin Taghabon, and Tyler Pollard.

We would like to acknowledge Claudia Spadafora for critically editing this essay.

JK would like to thank P.K. Rangachari, Stacey Ritz, Margaret Secord, Stelios Georgiades, and Manel Jordana for endless opportunities, guidance, conversation, and support. JK also thanks AM, from whom he has learned more than he could ever repay. JK was fortunate to study and engage in projects under the supervision of Del Harnish, and hopes he picked up enough of Del’s mischief in the time he spent with him.

References

[1] Snow, C. P. (Charles Percy), 1905-1980. (1959). The two cultures and the scientific revolution. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

[2] King, A. (1993). From sage on the stage to guide on the side. College teaching, 41(1), 30-35.

[3] Friesen, J. (2019, April 19). New metrics for Ontario university and college funding include employment and graduation rates. The Globe and Mail. Retrieved from https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-new-metrics-for-ontario-university-and-college-funding-include/

[4] Referring to Manichean religious beliefs about duality. Typically, about a good, spiritual world of light and an evil, material world of darkness. Read as “is such a black and white divide even possible?”

[5] Roth, P. L., BeVier, C. A., Switzer III, F. S., & Schippmann, J. S. (1996). Meta-analyzing the relationship between grades and job performance. Journal of applied psychology, 81(5), 548.

[6] Cain, P. (2018, September 13). One university’s secret list to judge applicants by their high schools – not just their marks. Global News. Retrieved from https://globalnews.ca/news/4405495/waterloo-engineering-grade-inflation-list/

[7] Accessibility for Ontarians With Disabilities Act, 2005, SO 2005, c 11, <http://canlii.ca/t/52pzh> retrieved on 2019-11-28

[8] Statistics Canada. 2016. Census Profile, 2016. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 98-316-X2016001. Ottawa. Version updated June 2019. Ottawa. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/prof/index.cfm?Lang=E, Nov 28, 2019.

[9] McLuhan, M. (1964). Understanding media: The extensions of man. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

[10] Postman, N. & Weingartner. (1969). Teaching as a Subversive Activity. New York, NY: Delta Publishing Co., Inc.

[11] “By making alienation ‘the key concept in the analysis of human situations since Marx’, Lefebve was opening philosophy to action: taken in its Kantian sense, critique was not simply knowledge of everyday life, but knowledge of the means to transform it” (Critique of Everyday Life, 6).

[12] Kanapa, J. (1947) Henri Lefebvre ou la philosophie vivante. La Pensee, no. 15.

Chaya Gopalan

My teaching career started with the traditional podium-style lecture, using chalk and a blackboard, just like I was taught. I soon realized that my approach had to change, as I was influenced by the body of evidence suggesting that lecture alone is not an effective way to promote deep and lasting student learning (Haxhiymeri & Kristo, 2014; Johnson, 2011; Lang, 2014). The lecture-based method of teaching has proven to be less engaging than inquiry-based education (Butzler, 2014; Larsen et al., 2019; Persky & Pollack, 2011; Rawekar et al., 2013; Simonson, 2014). Studies suggest that the lack of mechanisms to ensure intellectual engagement with the lecture results in a decline of student concentration after 10 to 15 minutes (Haxhiymeri & Kristo, 2014). Moreover, traditional lectures are not well-suited for teaching higher-order skills, such as application, analysis, and synthesis (Huxham, 2005; Young, Robinson & Alberts, 2009). An evidence-based, student-centred classroom that is rich in opportunities for collaboration and active learning contributes to student success (Freeman et al., 2014; Johnson, 2011; Kuh, 2007). Influenced by the literature, my peers, and educational conferences, I soon incorporated informal group activities and formative assessments into my teaching.

Recent advancements in educational technology, access to an increasing volume of scientific information, and a shift in expectations among millennial learners call for an alternative instructional approach (Johnson & Romanello, 2005; Mangold, 2007; Smith, 2014). As educational technology was transforming, I embraced the opportunity and became an early adopter of learning management systems, computerized exams, and lecture capture devices, among others.

Student-centred learning strategies have been shown to mitigate the limitations of the standard transmittal model of education by promoting student engagement and improving knowledge retention (Clark et al., 2011). Thus, the informal group activities that I once used as active learning techniques were replaced by formal, team-based learning activities. The use of team-based learning in the classroom was clearly engaging to the students. However, it also posed a new problem—not having enough time to cover the content, especially in my content-heavy health sciences courses. As I searched for a way to alleviate the constraint of time, a solution surfaced: the flipped classroom.

The flipped classroom revolves around assigning content in the form of readings, recorded lectures, and practice questions prior to class sessions. Students have their first exposure to content on their own, and class time is spent applying their new knowledge to real world situations. The in-class portion of flipped teaching (FT) offers an opportunity to work closely with students and explain particular questions in different forms to provide students with a multi-faceted approach to learning. The FT method also offers peer teaching, which is yet another opportunity for students to learn the content. FT is a hybrid educational format that shifts traditional lectures out of class, freeing up class time for student-centred learning. In this model, the students are first exposed to lecture content in their individual space (outside of class) using instructor-provided study materials such as guided readings and lecture videos. Later, under the guidance of the instructor, clarification, review, and problem-solving occurs in the group space (the classroom). According to the underlying theory and empirical studies, the FT model helps to overcome several challenges related to traditional lecture-based teaching. In a didactic lecture setting, students may be hesitant to ask questions, they may be multitasking, or they may not capture all of the key details because of the lack of repetition or the inability to type/write at speed while processing the information. In the FT mode, on the other hand, students may access content anytime from anywhere, and they can pace themselves by re-watching a video or revisiting the content. Thus, by allowing students to learn challenging material at their own pace, FT prevents cognitive overload of new information (Clark et al., 2011). Furthermore, FT provides a great opportunity to engage students in critical thinking through application, analysis, and synthesis, especially because the pressure of content coverage is now shifted to outside of class (Krathwohl, 2002; McLaughlin et al., 2014; O’Flaherty & Phillips, 2015). Furthermore, FT repetitively introduces concepts, thus bolstering student preparedness and student engagement in learning (Estes et al., 2014). The FT model is particularly helpful for students who are struggling to learn difficult topics (University of the Pacific, 2019). Overall, the FT method expects the students to be active participants in the course.

The NMC Horizon Report: 2014 Higher Education edition selected FT as one of their near‑term technologies that are expected to achieve widespread adoption in one year or less (Johnson et al., 2014). Team-based learning and case-based learning, when combined with FT, are among other approaches that not only maximize student learning but also to help students develop positive interdependence, accountability, and skills in communication and collaboration.

Retrieval is the reclamation of information that improves knowledge and strengthens skills through long-term meaningful learning (Karpicke, 2012). Repeated retrieval through exercises involving inquiry of information in a variety of settings and contexts is known to improve learning, and the FT model allows an abundance of repetition (Balota et al., 2006; Fritz et al., 2007). One crucial part of the FT model is in the design of class activities to engage students in learning and critical thinking (McLaughlin et al., 2014; O’Flaherty & Phillips, 2015). Another key factor that determines the success of FT is whether students complete pre-class assignments to immerse themselves in their in-class activities.

Pre-Class Activities

The utilization of resources by students typically meets significant resistance (Hessler, 2017). Students have a tendency, in general, to not complete pre-class assignments. Many factors can contribute to why students avoid taking advantage of their pre-class resources. Students may lack interest, motivation, or time to fulfill pre-class requirements, especially if the content is too challenging or not appealing. In addition, spending several hours outside of class towards pre-class resources requires self-discipline, good time management skills, and time commitment. The lack of time commitment from students results from being accustomed to the traditional lecture-based approach (Saumier, 2016). Even when the amount of work expected of them does not vary between teaching methods, students may perceive an increase in their workload with FT (Kember, 2004). Thus, the amount of work that students feel they must put into a FT course to succeed might be higher than the amount of work that they believe is necessary to keep up and to achieve the same outcome in a regular course (Deslauriers et al., 2019). The barriers to student preparedness could be overcome by designing activities that are challenging but achievable, including course content that is relevant and linked to their success, a positive atmosphere, and clear communication of student expectations (O’ Flaherty & Phillips, 2015). Assuming that students are successfully utilizing resources before their in-class session, the carefully designed active learning strategies in the classroom create opportunities for deeper understanding through application and analysis of the content.

A low-stake assessment helps instill a sense of accountability and encourages students to complete pre-class assignments. Primary factors to focus on for the pre-class content’s assessment is to test factual details and to remain on a knowledge level of Bloom’s Taxonomy (Krathwohl, 2002). Assessments of pre-class content could come in a variety of formats but are commonly quizzes, worksheets, or questions embedded into the lecture video that the students are expected to utilize in their preparation for in-class work.

In-Class Activities

The assessment of pre-class content not only provides a glimpse of student preparation but also reveals the topics with which the students typically struggle. Instructors must review students’ pre-class performance prior to scheduled class time to discuss those topics with which the students struggled. In addition, instructors should open the floor by providing an opportunity for students to identify topics that were not clear to them. Discussing those topics will allow more time to explain difficult topics in-depth. This review activity during face-to-face meetings also provides the chance for the instructor to reach out to students if they are not participating in the pre-class assignments.

The primary focus of FT is not only on pre-class assignments and assessments, but also on the in-class activities and assessments in which students will partake. Using this approach, instructors can guide students into a deeper understanding and comprehension of the material. Whereas pre-class assessments are meant to facilitate lower-order learning, in-class assessments and discussions focus on higher-order learning. Teachers who have had experience with FT recommend to not add more lecture material than originally planned during the scheduled in-class time (Hessler, 2017). With students coming prepared using pre-class content, it may seem like there is more time and that class can move along more quickly. Instead of adding extra content, however, one now has time for interactive in-class activities, discussion, and assessments at a more in-depth level.

In-class activities and assessments can take a variety of forms, such as discussing a case study, using clicker questions, problem sets, building a model, and many more. In addition to the delivery of course content, the active learning that takes place in the classroom shifts the focus from the teacher to the student and to student engagement with the material. Through active learning techniques and modeling by the teacher, students shed their traditional role as passive receptors by actively participating while attaining knowledge and skills; as a result, they are able to apply their knowledge and skills more meaningfully (Haxhiymeri & Kristo, 2014). Many studies have used group exercises in class (Gopalan, 2019; Gopalan & Klann, 2017; Hessler, 2017). Group work provides opportunities for students to meaningfully discuss, listen, write, read, and collaborate on the content, ideas, and issues of a specific topic.

Evaluation of Flipped Teaching

It is recommended that teachers collect students’ feedback on how students felt during the new process of learning in the FT method. A qualitative student survey early in the semester allows students to voice their concerns. It is not uncommon for faculty to become discouraged when asking students for their opinion early in their experience of an FT course, but this feedback is valuable because of its ability to provide information that can help improve the process. It can also offer new information that was not originally anticipated. Indeed, the topic of evaluations often brings more questions than answers. Finding valid and reliable evaluation tools to measure the effectiveness of FT may be a challenge. The use of standardized exams, such as unit exams, midterms, finals, and board exams, will most likely continue to be the mainstream evaluation method for student knowledge outcomes (Kuh et al., 2005).

With the appropriate design of pre-class and in-class assessments, instructors will have a greater chance of conducting a successful flipped classroom. Dedication, being open to feedback, and allowing enough time to prepare materials appropriately is crucial to success. With continued research on how to properly implement successful FT, this approach could soon become the norm for all students and faculty, just as it is for me.

Acknowledgements

Anna Rever’s assistance with literature and editing is sincerely appreciated.

References

Balota, D.A., Duchek, J.M., Sergent-Marshall, S.D. & Roediger III, H.L. (2006). Does expanded retrieval produce benefits over equal-interval spacing? Explorations of spacing effects in healthy aging and early stage Alzheimer’s disease. Psychology and Aging 21: 19–31.

Butzler, K. B. (2014). Flipping at an open enrollment college. ACS CHED CCCE 1–17.

Clark, R. C., Nguyen, F. & Sweller, J. (2011). Efficiency in learning: Evidence-based guidelines to manage cognitive load. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

Deslauriers, L., McCarty, L. S., Miller, K., Callaghan, K.,& Kestin, G. (2019). Measuring actual learning versus feeling of learning in response to being actively engaged in the classroom. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 166: 19251–19257.

Estes, M. D., Ingram, R. & Liu, J. C. (2014). A review of flipped classroom research, practice, and technologies. Higher Education 4: 7

Fritz, C. O., Morris, P.E., Nolan, D. & Singleton, J. (2007). Expanding retrieval practice: An effective aid to preschool children’s learning. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology 60: 991–1004.

Gopalan, C. (2019). Effect of flipped teaching on student performance and perceptions in an introductory physiology course. Advances in Physiology Education 43: 28–33. doi:10.1152/advan.00051.2018.

Gopalan, C. & Klann, M.C. (2017). The effect of flipped teaching combined with modified team-based learning on student performance in physiology. Advances in Physiology Education: in press.

Haxhiymeri, V. & Kristo, F. (2014). Teaching through lectures and achieve active learning in higher education. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences 5: 456.

Hessler, K. (2017). Flipping the nursing classroom: Where active learning meets technology. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Huxham, M. (2005). Learning in lectures do ‘interactive windows’ help? Active Learning in Higher Education 6: 17–31.

Johnson, A. (2011). Actively pursuing knowledge in the college classroom. Journal of College Teaching and Learning 8: 17–30.

Johnson, L., Becker, A.S., Estrada, V. & Freeman, A. (2014). NMC Horizon Report: 2014 Higher Education Edition. Austin, Texas: The New Media Consortium.

Johnson, S. A. & Romanello, M. L. (2005). Generational diversity: teaching and learning approaches. Nurse educator 30: 212–216.

Karpicke, J.D. (2012). Retrieval-based learning: Active retrieval promotes meaningful learning. Current Directions in Psychological Science 21: 157–163.

Kember, D. (2004). Interpreting student workload and the factors which shape students’ perceptions of their workload. Studies in Higher Education 29: 165–184.

Krathwohl, D.R. (2002). A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy: An overview. Theory into Practice 41: 212–218.

Kuh, G.D., Kinzie, J., Schuh, J. H. & Whitt, E. J. (2005). Assessing conditions to enhance educational effectiveness. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Kuh, G.D. (2007). What student engagement data tell us about college readiness. Peer Review 9: 4.

Lang, J. (2014). Learning on the edge: Classroom activities to promote deep learning. Retrieved from https://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/effective-teaching-strategies/learning-edge-classroom-activities-promoting-deep-learning/

Larsen, C.M., Terkelsen, A.S., Carlsen, AM.F. & Kristensen, H.K. (2019). Methods for teaching evidence-based practice: a scoping review. BMC Medical Education 19: 259. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-019-1681-0

Mangold, K. (2007). Educating a new generation: Teaching baby boomer faculty about millennial students. Nurse Educator 32: 21–23.

McLaughlin, J. E., Roth, M. T., Glatt, D. M., Gharkholonarehe, N., Davidson, C. A., Griffin, L. M. & Mumper, R. J. (2014). The flipped classroom: A course redesign to foster learning and engagement in a health professions school. Academic Medicine 89: 236–243.

O’ Flaherty, J. & Phillips, C. (2015). The use of flipped classrooms in higher education: A scoping review. The Internet and Higher Education 25: 85–95.

Persky, A. M. & Pollack, G. M. (2011). A modified team-based learning physiology course. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education 75: 204.

Rawekar, A., Garg, V., Jagzape, A., Despande, V., Tankhiwale, S. & Chalak, S. (2013). Team based learning: A controlled trial of active learning in large group settings. Journal of Dental and Medical Sciences 7: 42–48.

Saumier, L. P. (2016). Improvements of the peer-instruction method: A case study in multivariable calculus. Electronic Journal of Mathematics & Technology 10: 137–153.

Simonson S.R. (2014). Making students do the thinking: Team-based learning in a laboratory course. Advances in Physiology Education 38: 49–55.

Smith J.S. (2014). Active learning strategies in the physician assistant classroom-the critical piece to a successful flipped classroom. The Journal of Physician Assistant Education 25: 46–49.

University of the PACIFIC. (2019). Retrieved from https://www.pacific.edu/about-pacific/newsroom/2019/may-2019/flipped-classroom–luke-lee.html.

Young, M. S., Robinson, S., & Alberts, P. (2009). Students pay attention! Combating the vigilance decrement to improve learning during lectures. Active Learning in Higher Education 10: 41–55.

Jonathan Kibble

When I was in grade school in England in the 1970s and 80s, children were still mostly supposed to be seen but not heard. A swift punishment would often correct the errors in our ways, though the nicer teachers also rewarded our compliance. Teachers and textbooks were our source of knowledge, and their truths were rarely up for debate. This was a learning environment shaped by classical behaviorist learning theory. In 1969, the year before I was born, Postman & Weingartner published Teaching as a Subversive Activity. They envisioned an educational world where learners learned through asking questions (“Inquiry Learning”), with the goal of developing skills to solve real-world problems. Graduates would enter the world with a keenly developed “crap detector” in order to be engaged citizens, thriving in a world full of existential threats.

In Postman & Weingartner’s time, communism and nuclear war were high on the list of Western worries. In our post 9-11 world, these fears have changed to things like terrorism, climate change, and pandemics, but the case for learning to solve a good problem seems just as urgent. One seismic difference in today’s learning environment is how learners receive their information. I was always vexed about the risk of biased information coming from a mass media controlled by a few powerful men. Today, our learners have been liberated by the internet and its social media. Avalanches of information are delivered any time, any place, anywhere. Our new dilemmas are massive information overload, soundbite analysis, and polarization of viewpoints. In this new order, it strikes me that the need for one of those old “crap detectors” is more urgent than ever!

After high school, I began a lifelong habit of avoiding the real world as I went straight off to medical school. There, I literally received wisdom. Lecture upon lecture of wisdom. Looking back, drinking from that fire hose of knowledge largely prevented me from thinking for myself until well into the 1990s. At about that time, I got a scholarship to take a year out of medical school to complete a Bachelor’s degree. It was my first encounter with research, which led me next into a Ph.D. program. For the first time in my educational journey, I was confronted with the need to determine the direction of my own work, to ask questions, and to try to figure out the answers. I was finally doing some of that Inquiry Learning! It was a process that permanently changed who I am. I emerged with the confidence and ability to frame my own questions. I can find good information and assess its validity. I can draw evidence-based conclusions. I can usually work well with other people. Most importantly, I can passionately disagree with you and we can still be friends! Did I have to do a Ph.D. to experience these things? Today, I am a professor in a medical school. My roles have included being responsible for fostering Inquiry Learning, or what we now might call “student-centered learning.” This has been a pathway filled with both joy and pain—and a steady loss of hair!

So, what is student-centered learning? For me it is simply a philosophy that prioritizes the needs and interests of students. Compared to traditional programs, learning is more personalized. Students are allowed to set some of the learning agendas. They experience authentic learning activities, meaning that they get to tackle some real problems in real situations. Student-centered learning commonly includes a lot of social learning in teams. Faculty shape the process and spend more time giving feedback than lectures. The theoretical basis here has switched to social constructivism. Students build new learning on their prior learning. With the help of their teachers, learners internalize the knowledge and skills of their environment. Students take responsibility for their own learning and eventually gain autonomy. Shouldn’t be too hard, right?

For this piece, I was asked to comment on whether one can truly promote student-centered learning in a standards-based world. This gets at the idea of barriers, and one of them is certainly our conventional views on assessment and standards of achievement. My world is indeed constrained by externally imposed standards. Most of my learners are pre-clinical medical students who must get a great score on the United States Medical Licensure Exam (USMLE) Step 1 knowledge test to secure a good residency job later on. My other students are pre-med students who are taking the Medical College Admissions Test to enter medical school. All of these learners have their eyes firmly fixed on the prize of doing well on a standardized test. Doing wholesale student-centered learning in this environment is tough. There is a powerful informal curriculum that often drives the expectation that faculty should simply tell students what they need to know. Exposing these strategic learners to the sometimes messy and seemingly inefficient world of Inquiry Learning can place your teaching evaluations in peril! In this environment, my suggestion is to find the right dose of the medicine.

Much of the time we can easily align with the students’ most proximal goal of passing their external test. We can at least use active and engaging learning pedagogies to help them master the core of knowledge. Instead of just lectures or readings, we can infuse short videos, games, simulations, case problems, collaborative exercises, and the like. We can also use authentic experiences to foster learning of other key competencies that are not on The Test. For example, I can tap into a medical student’s emerging professional identity and have them work some of the time with real patients. Here, they may need to resolve an ethical dilemma, demonstrate reasoning skills to make a diagnosis, or master communication skills to give bad news. There is still good alignment with their ultimate goal of being a clinician, and there is engagement with a real-world problem. We can also reserve part of the overall curriculum footprint for project-based learning or research. In this part of the program, students can follow their own passion and be guided to experience the component parts of the discovery process. Even if you are teaching in a program where conventional knowledge standards are prominent external requirements, the curriculum can still prioritize lifelong learning skills by including inquiry and discovery.

Another challenge in our standards-based world is the narrow traditional viewpoint on how to fairly assess students. The notion of producing an “equal” assessment when we might have one hundred students all doing a different project is not as hard as it first seems. Rubrics that clearly describe the generic elements of hypothesis or question development, information gathering, study design, data collection, data analysis, and interpretation are readily available. After all, life is not a multiple-choice exam (though it is a cumulative one)! Speaking as someone who has given workshops on how to develop excellent multiple-choice exams, I am as much a fan of a good reliability coefficient as the next person, but a more creative mindset is needed to assess student-centered learning outcomes. To assess learners as they develop competencies, best practices include a shift to more frequent, low-stakes assessment with rich feedback about progress. Triangulating several measures over time allows us to determine when students have achieved competence.

This leads me to final thoughts about the challenges we face as faculty in delivering more meaningful learning. Another great prompt for this piece was, “will respecting an individual student’s autonomy as a learner still do justice to all other students, particularly in a world of limited resources?” Part of this we have already discussed—the need to create equitable assessments when students are each doing their own projects. My other thought relates to faculty resources, both in terms of faculty number as well as how we are deployed. There is no doubt that our ability to guide students through the inquiry process is more resource intensive than the traditional information-delivery mode of curriculum. A common issue is simply an adverse faculty-to-student ratio, which at some point does become limiting. These days, faculty spend a lot of time serving compliance systems such as accreditation, financial audit, effort reporting, research ethics, conflict of interest, grant reporting, and a growing list of metrics needed for knowledge managers to assure our excellence. While all of this is well intentioned, it takes us away from our primary missions of teaching and research, and it consumes a lot of human resources that are no longer available to deliver education. My advice is to stop filling out all those forms, as it only encourages them! More seriously, faculty need to be advocates for the education mission at every opportunity, from long range strategic planning to annual budget allocations.

It is not just about the number of faculty but also whether we and the institution both buy in to the idea of student-centered learning. Maybe you are strong enough to be a maverick who can swim against the tide. I did not know them, but I imagine that Postman & Weingartner and the late Del Hamish, who inspired this collection, probably fit this mold very well. Hopefully, you don’t need to be an outlier and your institution already values or even requires Inquiry Learning. Successful transition to student-centered approaches needs good faculty development. We were not raised as professional educators and many of us had those old behaviorists as our role models. We need help to rethink and redesign learning activities, to become better facilitators, to give effective feedback, to assess differently, and so on. Organizational buy-in has several other facets. Institutional values have to be apparent through actions like how we schedule classes, the facilities and resources provided, and the credits available for the work. This prevents a hidden curriculum from developing that pays lip service to, but undermines, student-centered learning efforts. Leadership needs to be supportive of the faculty engaged in this effort so that faculty are liberated to take some risks without the fear of risking their own career advancement, especially if student evaluations dip. We can do excellent student-centered education, even with limited resources, but alignment of philosophy from the curriculum committee, leadership, faculty, and students makes it so much easier.

Fifty years after Postman & Weingartner, we have made progress. In the intervening years, we have seen blue ribbon reports like Vision and Change in Undergraduate Biology Education: A Call to Action make specific recommendations for a shift to student-centered classrooms and for the inclusion of real-world research experiences into the curriculum. Have we fulfilled all of the vision yet? No. But it is no longer subversive to expect that all our learners will graduate with the ability to think and advocate for themselves in a complex world. Over the last 10-15 years, I have met many faculty with the necessary passion and skills to deliver such an educational outcome. In honor of Del Hamish, and the others that came before us, let’s keep moving onwards and upwards together!

References

Bauerle, C., DePass, A. & Lynn, D. ET AL. (2011) Vision and Change in Undergraduate Biology Education: A Call to Action. Final Report of a National Conference Organized by the American Association for the Advancement of Science, July 15–17, 2009, Washington, DC. Washington, DC: American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Postman, N. & Weingartner. (1969). Teaching as a Subversive Activity. New York, NY: Delta Publishing Co., Inc.

Damien Joseph

Can one truly promote student-centred learning in a standards-based world? In theory, no, this would not be possible. The individuals that comprise a classroom are diverse beings with different experiences and interests. Accordingly, we wouldn’t expect everyone to have the same aptitude for the different subjects that we evaluate. Nor should we want this—this is the beauty of student-centred learning. If we are serious about this mode of learning, then we need to do away with standards as we know them. Why belabour the budding physicist with having to excel in English class? Or the passionate artist with chemistry lessons? We all have a natural proclivity for certain things over others, so why not focus on honing the craft we enjoy?

In fact, student-centred learning better fits the world that we are heading towards. That is, as occupations become increasingly automated, there will be a shift towards more creative-based work. And the best way to inform work like this is by drawing upon the unique experiences and lessons that each person possesses. Let each student learn of their own volition and discover for themselves the things that intrigue them. This is how we cultivate life-long learners—by showing them how fun and wondrous an endeavour learning can be.

Not to mention, just because a student may initially be put off by a certain subject, it does not mean that they will never explore it for themselves in the future. As we pursue our interests, we soon discover that there are innumerable threads that connect each interest to other, seemingly disparate, things. For example, the artist who initially detests all things mathematical may find themselves enraptured by the ubiquity of the golden ratio within nature. Then, they may choose to learn more about it to further inform their own artistic works.

However, if we force everything down the throats of students and expect them to be good at everything from the get-go, they may learn to simply hate the things they aren’t immediately good at and avoid these things like the plague. We must avoid this at all costs—especially when grades are a metric upon which many students hinge their self-esteem. As the saying goes, “if you judge a fish by its ability to climb a tree, it will spend its entire life believing that it’s stupid.”

That being said, there is a tremendous amount of value to be derived from an education where one is exposed to all the different areas of study—especially considering that change is a pervasive part of our lives and we may realize that what we initially thought we wanted to pursue was in fact misguided. In this scenario, having a broad education provides an excellent platform to reassess the direction one wants to follow. Using standards that apply equally to everyone is not the way to go about this.

Ideally, we would work with each student to develop a unique education plan for them that would account for their unique aptitudes for different subjects and would allow them to cultivate the hidden potential within them. This would address the problem of students who have trouble picking up a subject being left behind and students who excel being held back from learning at a higher level than what is being provided.

We need to teach students how to think and learn for themselves; not how to learn for a test. We need to teach them how to think critically about problems and find ways to be more creative. Students are losing motivation because they’re far removed from the education they are getting. They aren’t learning for themselves, and the knowledge they gain seldom persists past the exams they write.

The current standards-based education system that is peddled is archaic; it is an artifact of times long past. The world is changing at a rapid rate while our education system is frozen in time. What use is education as we know it if what we learn is outdated by the time we graduate?

Debra L. Klamen

As I began to reflect on the role of student-directed learning in a standards-based world, as Senior Associate Dean of Education and Curriculum at Southern Illinois University School of Medicine (SIUSOM), I immediately began to think about its role in medical education—surely a standards-based environment if ever there was one.

My first emotional response was, “What is its role? Essential!” “Can/Should we promote it? Absolutely!” I hope by the end of this short article you, the reader, will agree with me.