eCampusOntario Open Competency Toolkit by Dennis Green and Carolyn Levy is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

eCampusOntario Open Competency Toolkit by Dennis Green and Carolyn Levy is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

There is a lot of activity and growing interest internationally around micro-learning opportunities, which includes both micro-credentials and digital badges among others. eCampusOntario has been working to support micro-learning opportunities over the last several years, and this toolkit is part of an initiative to support the development of common, open competency frameworks for in-demand sectors of the labour market. These competency frameworks will support the development of micro-learning opportunities in alignment with the eCampusOntario Micro-Credential Principles and Framework and form a key cornerstone for future workforce development activity.

The COVID-19 pandemic and the resulting economic disruption has magnified the increased need for cross-occupational mobility, as some sectors are facing a lengthy recovery, while others are seeing sudden and unanticipated increased demand for workers with the right skills. While the development of common competency frameworks is not intended as a direct response to post-COVID workforce recovery and realignment, having such frameworks in place will provide for both horizontal (cross-sectoral and cross-occupational) and vertical (within occupations and sectors) skill progression, certification, and career pathways for Canadians from all walks of life.

Other jurisdictions, such as Europe, Australia and New Zealand have well defined nationally validated competency and qualification frameworks but such a formalized system is lacking in Canada at the moment. The US, although it lacks a formal national competency and qualification framework, has amassed a large amount of data within its O*Net system that tracks occupational requirements across a number of domains, from abilities, interests, knowledge and skills, to work environments, context and values. There are also a number of international initiatives underway to look at better ways of aligning competency definitions, terminology, and micro-learning opportunities across the globe, all of which will lead to more consistent and responsive ways to react to the rapid pace of change in the workforce.

Through this toolkit, eCampusOntario is developing the foundation, structure and tools to support the iterative development of open competency frameworks. If this is done well, it will pave the way for much more consistent and efficient work in this area for years to come. The result? Increased efficiency in both time and cost for others building common competency frameworks across in-demand industry sectors.

A major challenge that comes with developing competency frameworks across multiple industry sectors is ensuring that a common language and tools exist for the development of complementary competency libraries that are open, shared, and scalable. The language that is used in different sectors to describe the same skills or similar work activities varies, and industry sectors or occupational groups (such as professional associations) often develop their competency frameworks in silos. Duplication of effort and lack of transferability become stumbling blocks.

Compounding this are issues that persist with many sets of existing competency frameworks and occupational standards. These include lagging content development and revision cycles, misalignment between standards and assessment tools, and reliance on very small groups of people during input and validation processes. Often this stems from a combination of factors, but it is something that can be addressed by a well thought out and methodical approach to developing competency definitions and frameworks. This toolkit is intended to help address these issues.

In addition to supporting well-constructed competency frameworks, this toolkit is also intended to increase the openness of competency frameworks. By open, we mean that resources, tools and practices are free of legal, financial, and technical barriers and can be fully used, shared and adapted in the digital environment.

This toolkit was developed using a design and validation process that includes contact with both industry and education, in order to develop relationships that will support the socialization of the resources upon completion.

The toolkit is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-SA 4.0) license , and is intended to be shared and revised. As we will explore within the various sections of the toolkit, competency frameworks and the tools that are used to develop them need to be fluid, living, and breathing documents that can adapt to change and evolve over time.

This toolkit has two main purposes. The first is to foster the development of open competency frameworks that can be shared across industry sectors and for different end users. From this perspective, the toolkit may be used in different ways by different people. Some examples include:

The second purpose is to provide guidelines and good practices for people developing competency frameworks. There are sections of the toolkit dedicated to developing and writing competency descriptions as well as ways of grouping and clustering competencies to build frameworks.

We recommend that you begin with the Chapter on “Defining Competence.” This chapter outlines key terminology used in this toolkit and provides definitions for the terms “competent” and “competencies.” Even if you are experienced in developing competency frameworks, it’s important to grasp how these terms are being applied within the toolkit. Given the lack of agreed use of the terminology across sectors, it’s important to establish a shared understanding for the purpose of developing open competency frameworks. Once you are familiar with the terms, feel free to access the chapters as you need. If you are new to competency frameworks, it’s probably best to work through each chapter sequentially.

This toolkit would not have been possible without the support of eCampusOntario and a team of people representing a wide range of perspectives. We also want to thank the many people who participated in the review and validation of this toolkit who are not listed specifically.

These include:

Project Team

Dennis Green

Carolyn Levy

Our Working Group Members

Vivian Forssman

Lyne Marcil

Fiona McArthur

Judene Pretti

Evan Tapper

eCampusOntario Staff

Emma Gooch

Lena Patterson

Cindy Ly (Cover design)

Graphics

Caroline Mayhew

eCampusOntario is a not-for-profit organization funded by the Government of Ontario that supports Ontario’s colleges, universities, and Indigenous institutes. We build systems that are open, collaborative, and responsive to shifts and opportunities in the educational landscape to connect our campuses to the future of learning.

In this section we will look at the basis for competency frameworks, both broadly and more specifically within the context of this toolkit.

What do we mean by competence?

How does competence change over time?

Defining competence is no easy task. There is wide variation regarding the use of the term and oftentimes this causes confusion when trying to develop a competency framework. Given the lack of shared understanding, it is necessary to define it for use in this toolkit. According to the Oxford English Dictionary , Competence (noun) “is the ability to perform to a specified standard.” Competence involves successful performance in the world of work and learning. Effective performance requires both the skills to function effectively and the knowledge and attributes (attitudes and values) to apply those skills in routine and non-routine situations.

The term ‘competent’ (adjective) is used to describe individuals or groups (such as a competent person or a competent organization) and can be used in both broad and narrow contexts.

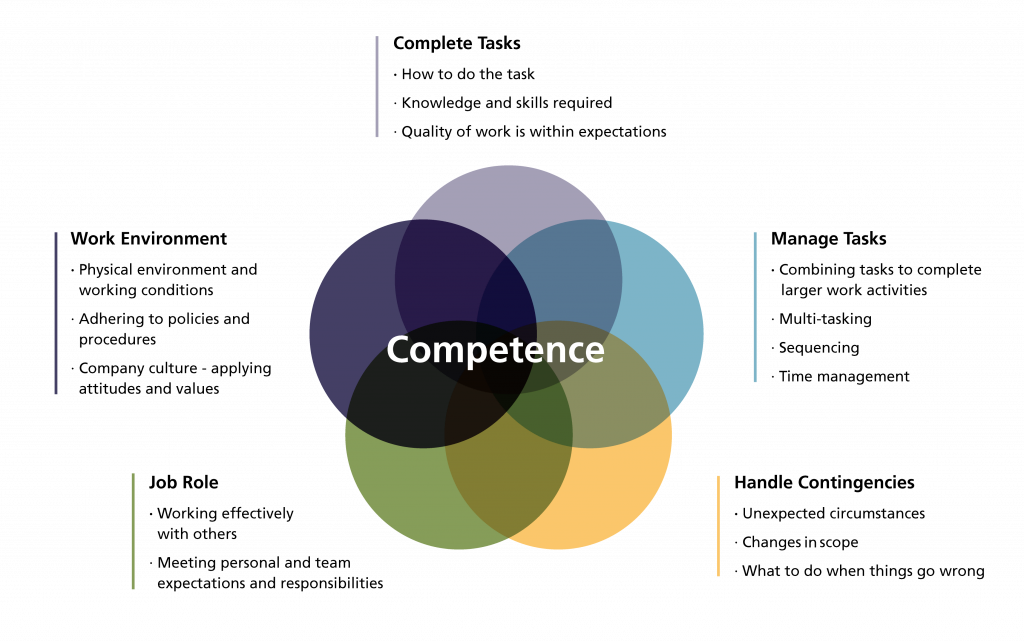

Being competent means being able to perform a task or an activity consistently over time and in different situations. To determine consistent performance it’s important to consider the following: :

These situational factors are important when developing competency frameworks. It’s also important to note that competence changes over time; for example, if a situation changes the level of competence required to perform to the agreed standard may change. Competence is fluid in nature and should be considered at all stages of competency framework development.

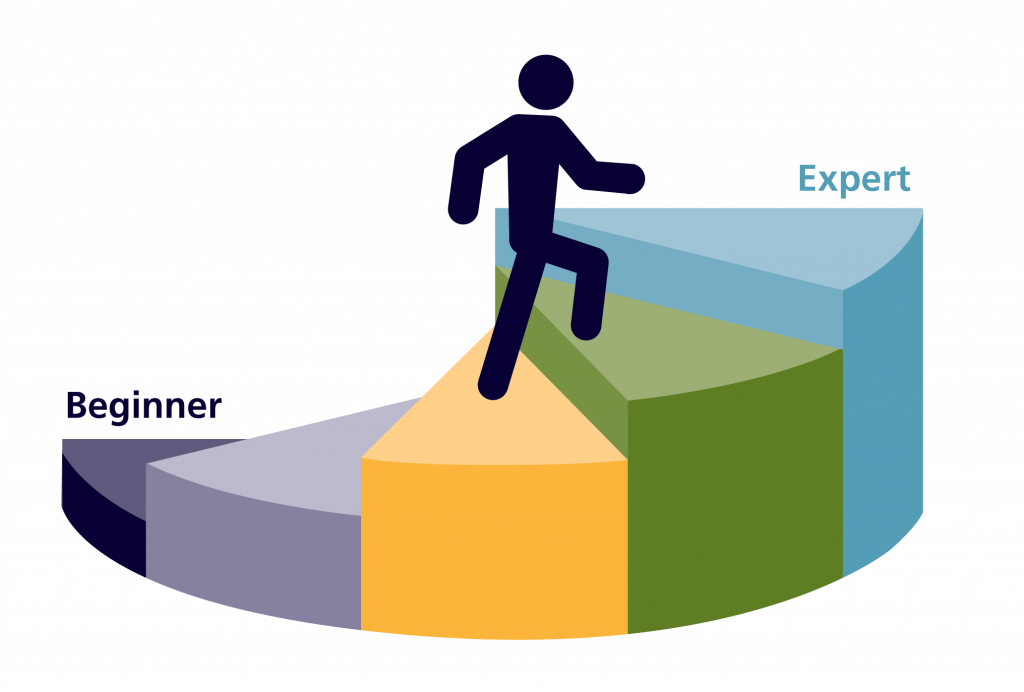

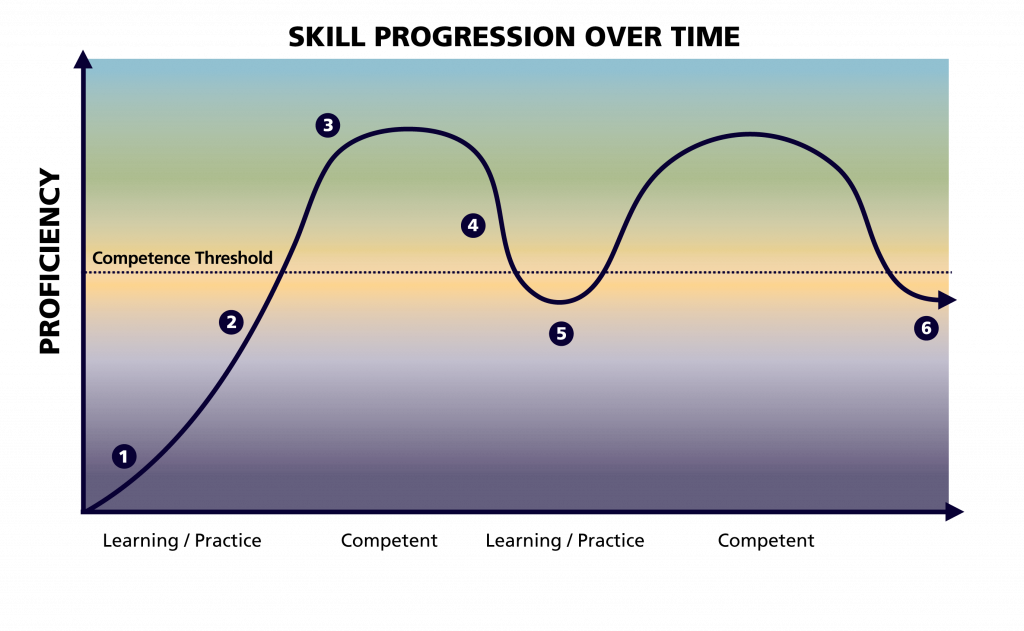

If there is one thing to keep in mind, it’s that competence itself is fluid and occurs as we learn to do things. There are many different descriptions of what that the journey towards competence looks like, but there are a few common themes on the continuum from beginner to expert (a proficiency scale).

Most models of skill acquisition look at proficiency scales as being linear, but in actuality, the journey can be more circular or branching, depending on a number of variables, such as complexity, pace of change, and the frequency that the activity is put into practice.

For example, let’s take a common activity that a large number of adults can do competently – driving a car – and see how this model of skill progression applies.

Keep this journey in mind (e.g. beginner to expert) as we look at how to develop a competency framework.

There may be situations where some competencies are critical to performing a work activity, in which case having confidence in the individual’s ability becomes a significant factor. For these situations, how often and in what manner the competency is being measured is important. Descriptions of competent performance are necessary so that the expected performance can be measured. Assessment is not always directly built into a competency framework, but the structure of how competencies are written needs to make assessment possible. Without this, there are too many variables, and the link between measuring competent performance and an individual’s demonstrated actions may be broken.

Another reason why competence is important is that different job roles may have different requirements in terms of the level of proficiency required in the same area. For example, many jobs have an expectation that everyone has a basic level of proficiency in using common office applications like word processing, spreadsheets, and presentation software. Certain roles may require different levels of competence, as those in marketing and communications might require expert proficiency in using presentation software, and finance roles may require expert proficiency in using spreadsheets. Moving between roles often requires some additional learning and practice in order to meet those expectations.

The need to identify the level of proficiency and to construct competencies that allow for assessment are reasons for having well-defined competency statements and descriptions.

A competency describes the ability to use a set of related knowledge, skills, and attributes required to successfully perform activities and tasks in a defined setting. This might seem straightforward but there is no agreed upon definition of competency. As the workplace and educational sectors debate the use of the term, we are going to propose some definitions that will help you build a competency framework.

For the purposes of this toolkit and for clarity, we differentiate between:

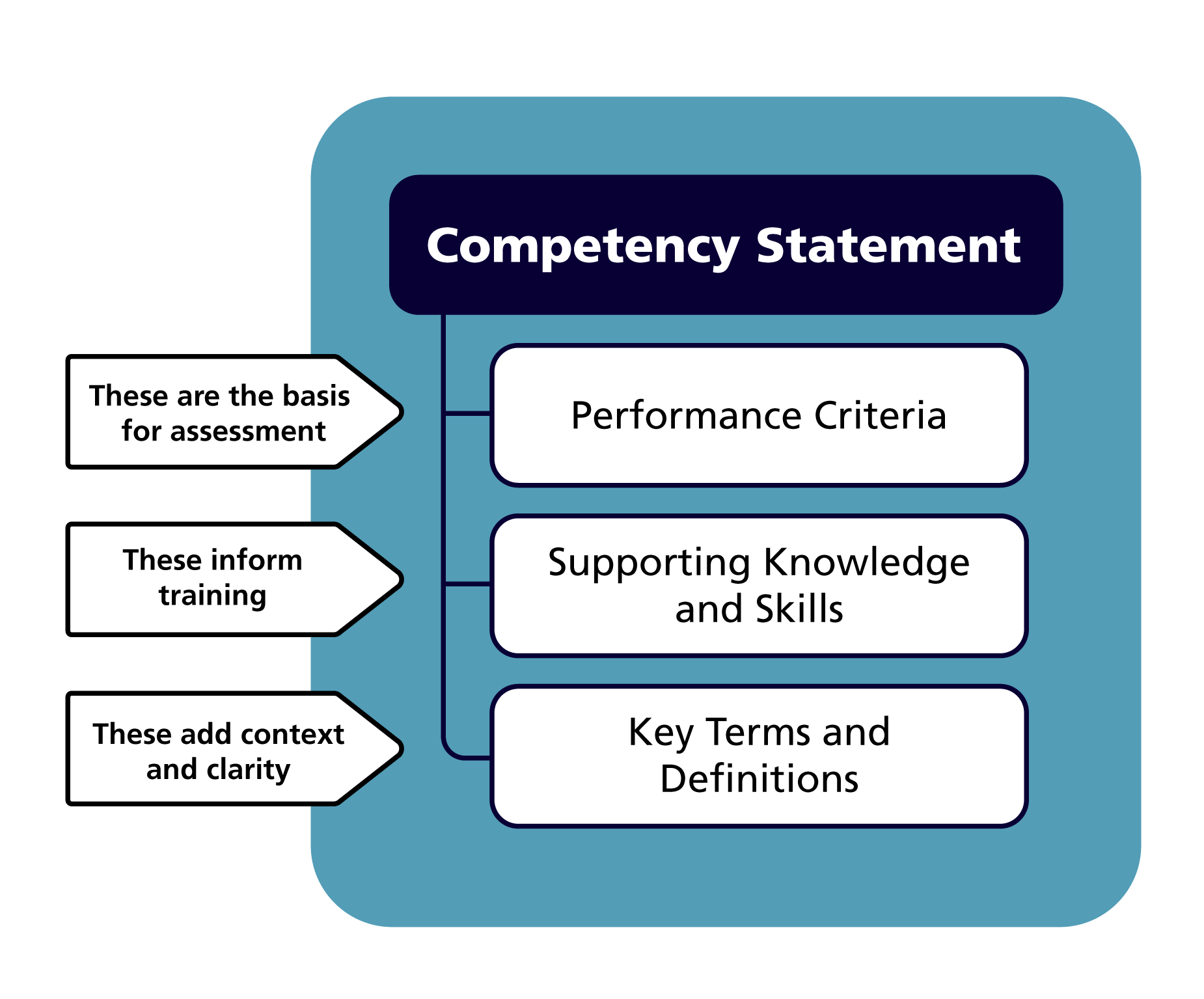

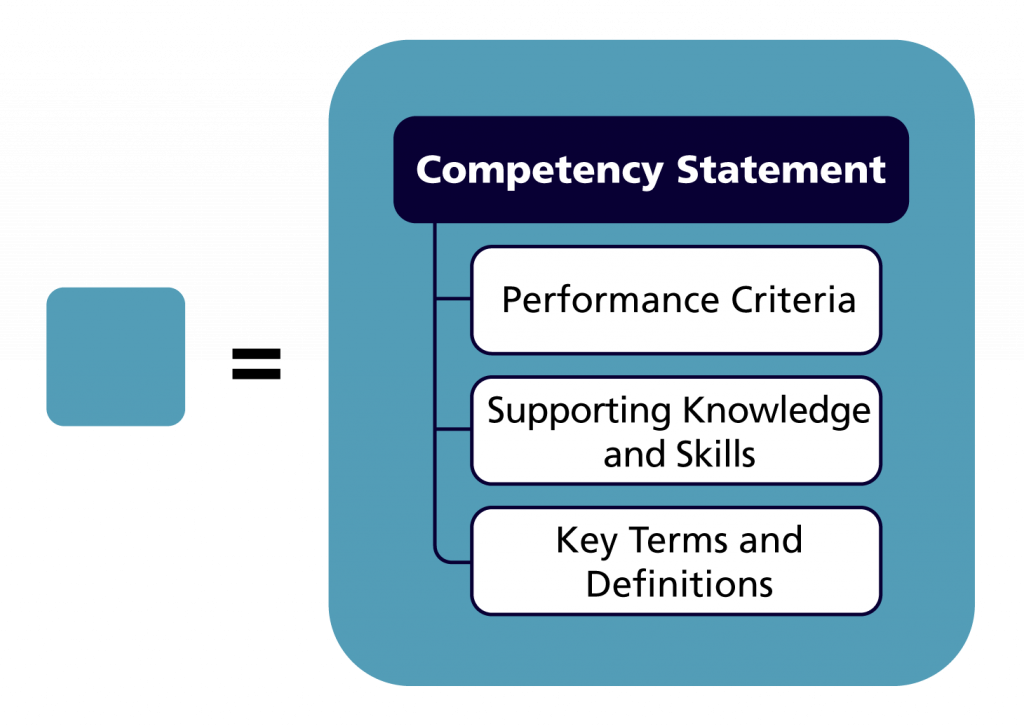

When using this toolkit, we will refer to individual competencies (or a competency) as consisting of:

While this interpretation is far from universal, it lays the groundwork for using competencies as a foundational piece of a competency framework.

Competencies are comprised of some key components:

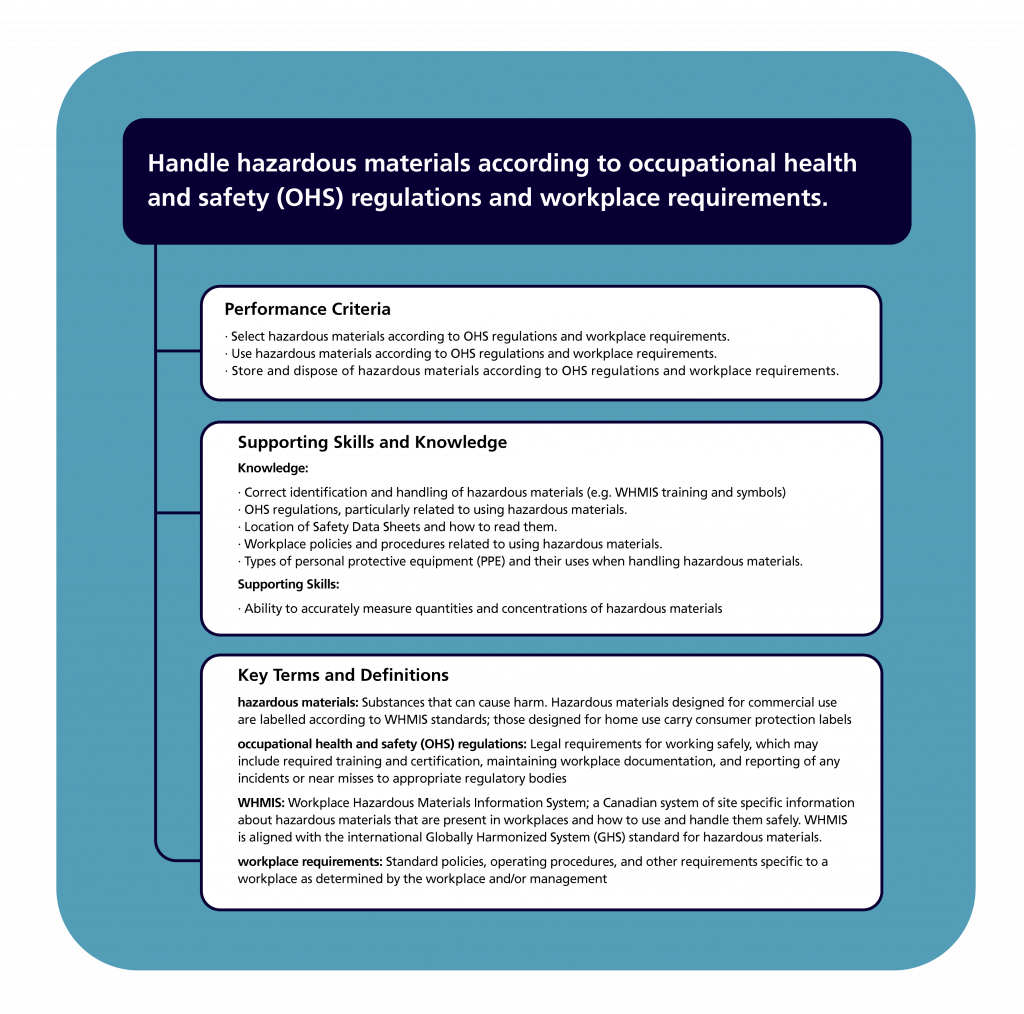

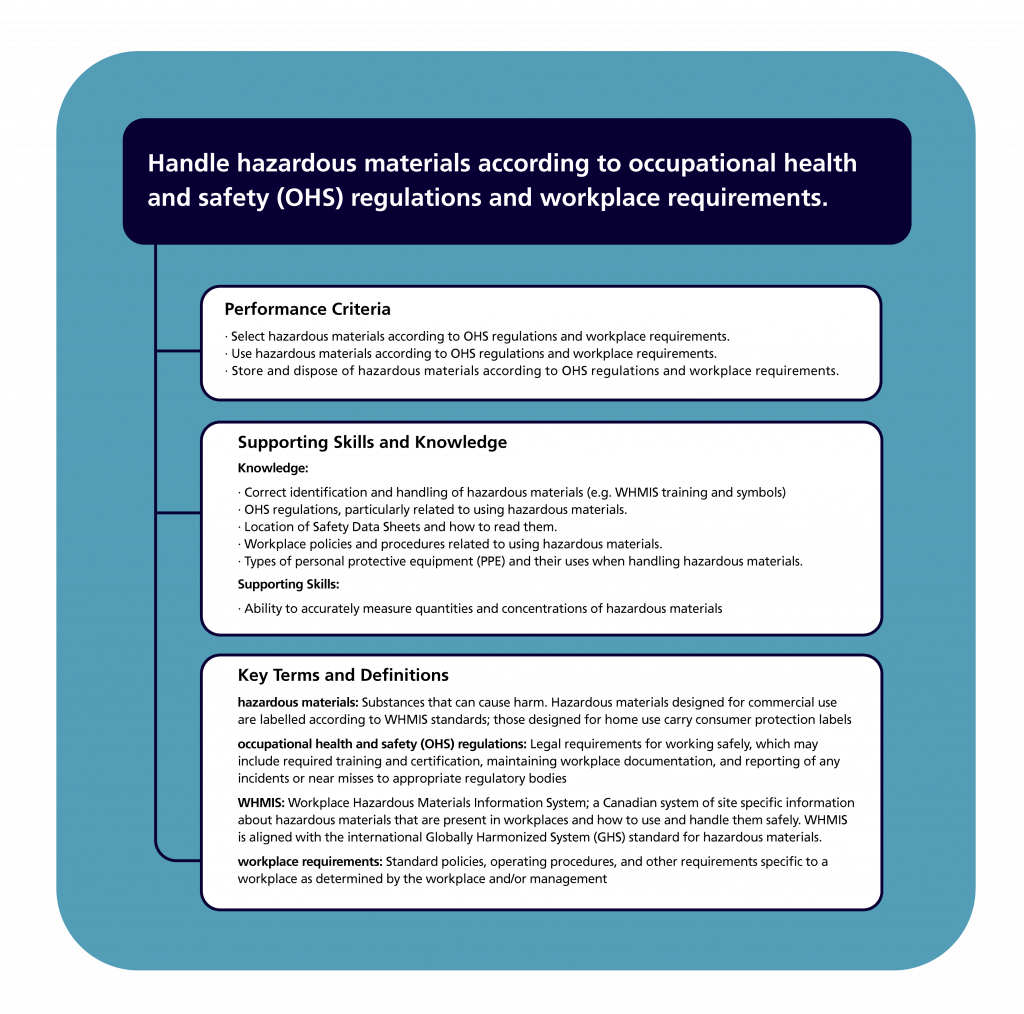

Take a moment to review the sample competency below which includes examples for each of the structural components.

Handle hazardous materials according to Occupational Health and Safety (OHS) regulations and workplace requirements.

Knowledge:

Skills:

| hazardous materials | Substances that can cause harm. Hazardous materials designed for commercial use are labelled according to WHMIS standards; those designed for home use carry consumer protection labels |

| occupational health and safety (OHS) regulations | Legal requirements for working safely, which may include required training and certification, maintaining workplace documentation, and reporting of any incidents or near misses to appropriate regulatory bodies |

| WHMIS | Workplace Hazardous Materials Information System; a Canadian system of site specific information about hazardous materials that are present in workplaces and how to use and handle them safely. WHMIS is aligned with the international Globally Harmonized System (GHS) standard for hazardous materials. |

| workplace requirements | Standard policies, operating procedures, and other requirements specific to a workplace as determined by the workplace and/or management |

When it comes to creating or revising a competency framework, it’s important to consider the components of each competency. To ensure that you capture the necessary information to build your competency framework, we propose the following components, which align with the templates we provide in the toolkit.

Title (or Name) – A short name that identifies the competency and is useful in distinguishing it in the framework. Taking the action verb and context from the competency statement is a good place to start.

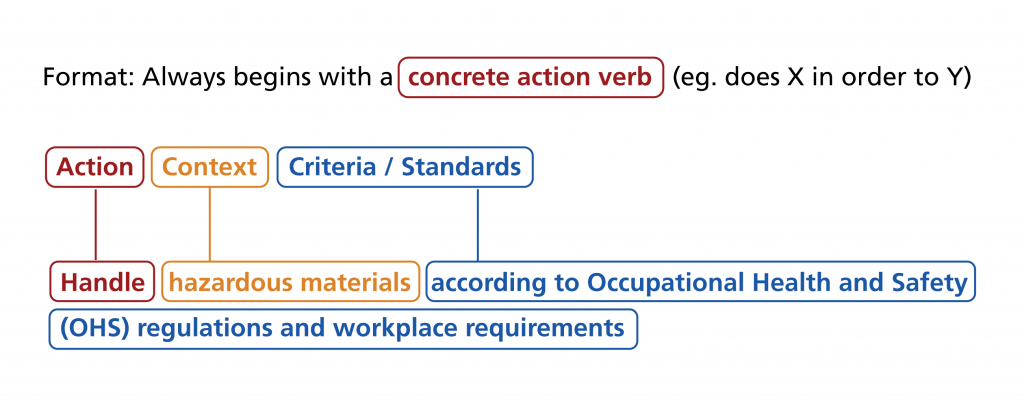

Competency Statement – A descriptive statement that states what a competent individual is doing, and in what context.

Defining Terms:

Concrete Action Verb = a measurable verb that states actions which can be observed and measured when used in the context of an activity or task.

Context = What the nature of the action is (i.e. the object of the verb)

Criteria/Standards = specify the criteria for expected performance (e.g. to what level, to which standard, scope etc.)

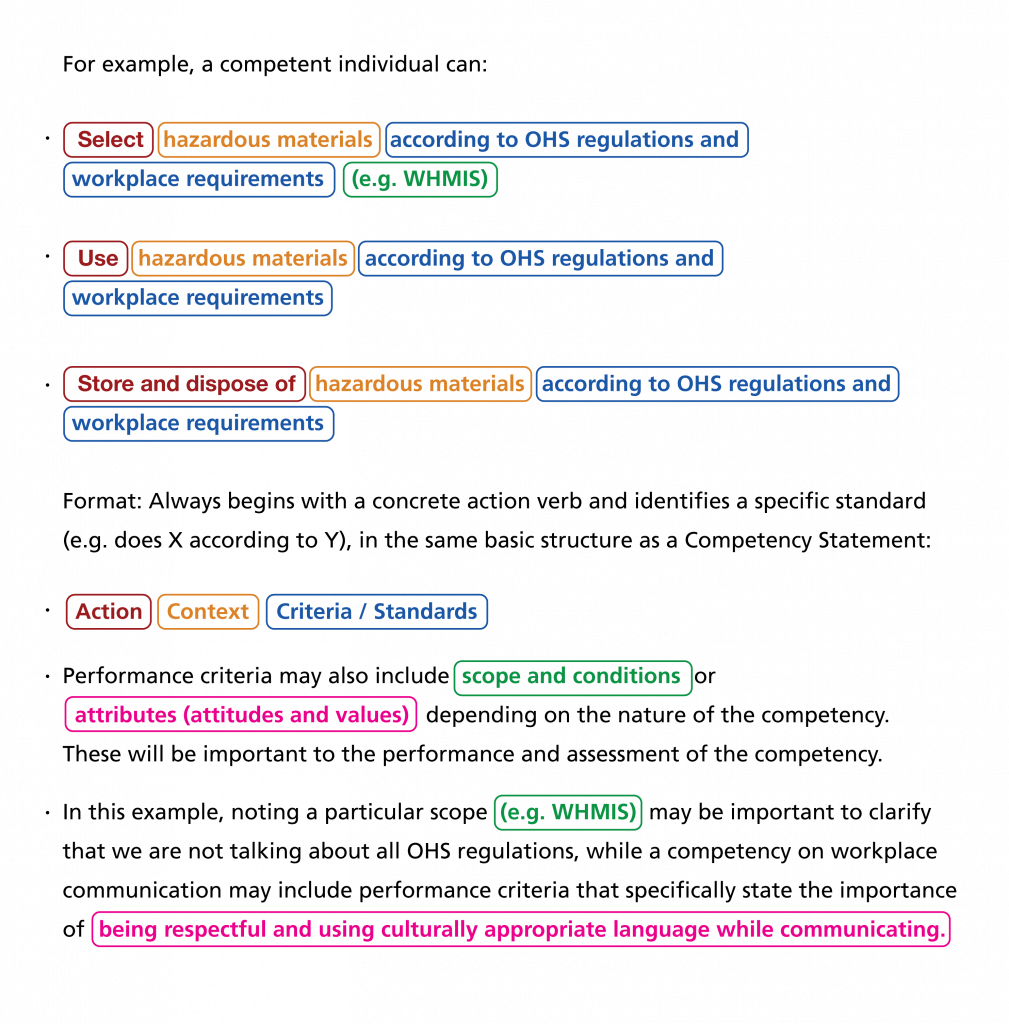

Performance Criteria – A list of measurable outcomes required to demonstrate proficiency in the competency.

Note: Expected performance criteria can look very similar to a competency statement. So, what’s the difference? Expected performance criteria are all the observable behaviours or sets of activities that a person must be able to do to demonstrate the competency. In order to achieve the competency listed above in the competency statement, the performance criteria list what a competent individual can do. In particular “handling” would include selecting, using, storing, and disposing of hazardous materials.

For example, a competent individual can:

Supporting Knowledge and Skills – What do you need to know, and be able to do in order to achieve the competency? These inform training requirements and learning outcomes.

Key Terms and Definitions – A list of key terms and definitions required to provide clarity about the descriptors used in the competency and/or performance criteria statements. Such terms are often bolded in the statements or compiled in a central glossary. Definitions can limit scope or identify variations in scope.

The crucial information you need to have for developing a competency framework is:

What you include in your framework beyond these key components depends on the purpose of the framework and who is using it. The next section goes into more depth on the purpose of frameworks, which will help guide the development of your framework, and the additional components below are included in the templates and examples we provide in the toolkit.

Context and Examples – These are not always included in the description of individual competencies but are important to a framework. The templates found in the appendix includes places to capture this information.

Learning Content / Links

Assessments

Connections to (or within) a Competency Framework – Categories and other links

Next, we’ll look at competency frameworks, their uses, and their key components.

What are competency frameworks?

Uses for competency frameworks

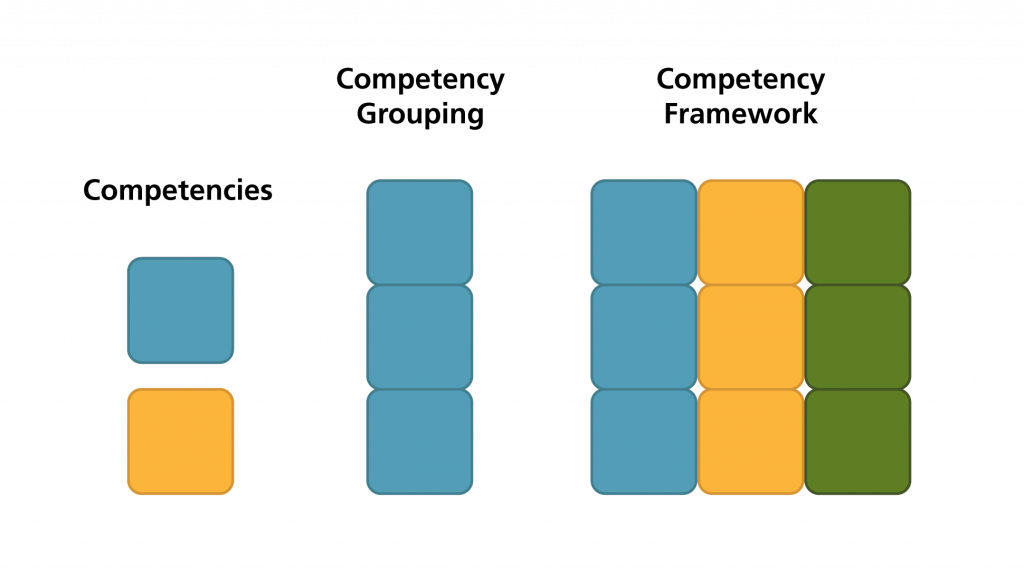

Competency frameworks are simply a combination of competencies that have been organized in some fashion, and usually consist of a minimum of three components:

A competency framework may also include additional information, depending on its use case and intended audience. These could include information on specific occupations or sectors, link to training and/or certification requirements, or may identify skill or competency areas that overlap with other frameworks, etc.

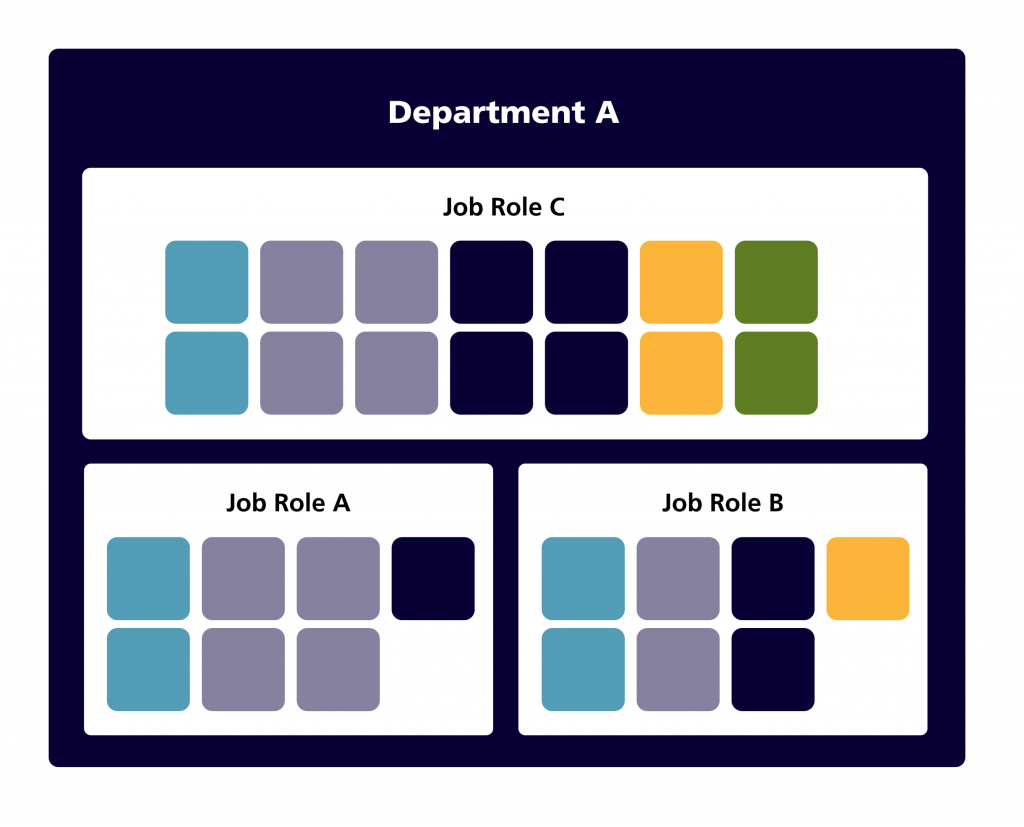

Competency frameworks can be big or small, and evolve over time. The simplest and smallest example of a competency framework might be a job description. It outlines the skills, knowledge, and attributes required for a single position, but likely will include some common, shared competencies that relate to other positions, and some functional or technical competencies specific to the role.

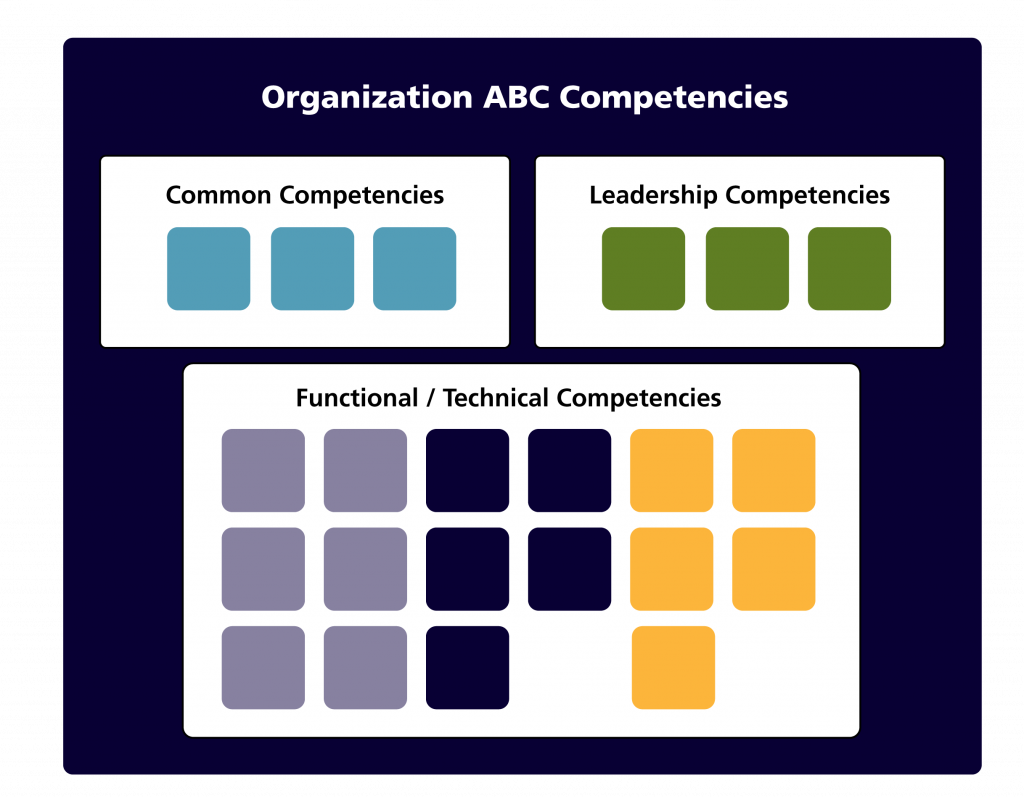

Although a competency framework that includes a single job description is unlikely, an organization may well have a small framework that includes all the competencies required across multiple job roles within each department and across the whole organization.

At the opposite end of the spectrum, a competency framework that covers an entire continent, like the European Skills/Competences, qualifications and Occupations framework (ESCO) consists of over 13,000 competencies tied to thousands of occupations and qualifications, and is extremely complex in the number of hierarchies and layers of information (taxonomies) that it contains.

Later on in the toolkit we’ll look specifically at ways to use competencies and groups of competencies within a framework.

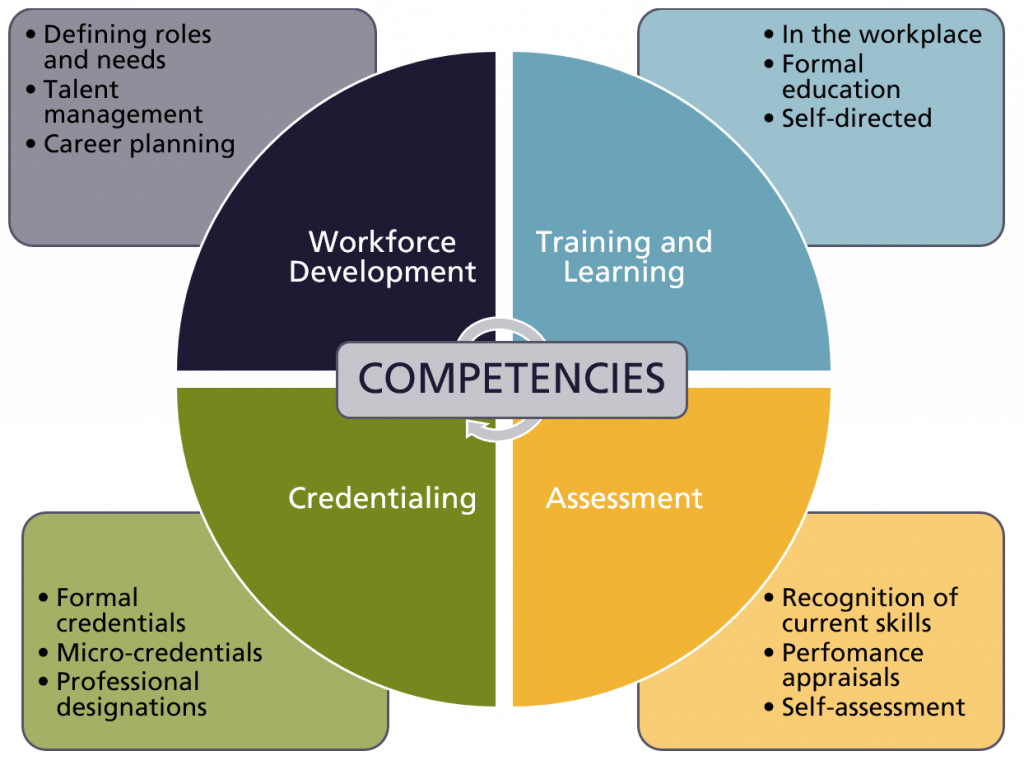

Competency frameworks define the competencies needed to identify, evaluate, and recognize effective performance, typically in the workplace as attached to a job role or occupation. While the range of uses for competency frameworks is wide (some lists include over 100 end uses), there are a few common reasons why a competency framework may be developed, all of which may be applied in either a workplace or an educational context. The language used in each of those settings may vary, but there are four main contexts and primary uses.

| Context | Use |

| Training and Learning | Developing individuals and teams through teaching and learning activities |

| Assessment | Evaluating individual and team performance in formal and informal ways |

| Credentialing | Recognizing achievements and issuing records of achievement |

| Workforce Development | Identifying individual, organizational and sectoral needs, career planning, and managing talent |

Well-designed competency frameworks support training and learning, assessment, credentialing, and workforce development in different ways. All of these uses are also interrelated, as credentialing and workforce development include some form of training or learning and assessment.

Most competency frameworks are connected to occupations and/or job roles in some way. Among frameworks that are built around occupations and job roles, the focus, structure, and use varies greatly, primarily driven by the type of organizations and stakeholders developing and using the framework.

Many competency frameworks are built around an occupation or group of related occupations in an industry sector. They define expected behaviours and performance associated with occupations, as well as outlining career progression between occupations and competencies that are common to many or all of the occupations within the framework. These may form the basis for licensing, continued professional development, specialization, or may link directly to courses and/or certifications issued by the same body that developed and manages the framework. Users of such a framework may include people working in the sector and/or specific occupations; people who are involved in delivering training and certification; and people looking to enter a career in one of the related occupations.

Larger organizations may have their own competency frameworks, which have been developed specifically for the purposes of workforce planning, performance management, and career progression. These frameworks typically focus less on formal certifications and tie directly into performance review cycles and professional development. Company-wide values or desired attributes often will be defined as core competencies within a framework of this nature. Users of this type of framework would include people in HR, employees and management within the organization, those designing or delivering training for the organization, and job seekers.

Governments and government organizations use competency frameworks for a range of uses, mostly linked to workforce planning on a macro scale. These frameworks are often broken down by sectors or occupational groups that are national in scope and sometimes tie into national and even international qualification frameworks. These frameworks are used for strategic decision making for things like the education system, career planning by those entering the workforce, and may form the basis for the evaluation of an individual’s skills for the purposes of immigration, skill recognition, or transferability between occupations.

Increasingly, the education system (both in the K-12 and post-secondary contexts) is using competencies and competency frameworks to link educational pathways and outcomes with workforce demands and career paths. Generally speaking, this has been most widely used in connecting existing external competency frameworks to formal learning, rather than developing new competency frameworks. This trend is certainly on the rise in North America and well-established in other jurisdictions that have strong national systems that connect competencies and qualifications.

Educational institutions and/or government bodies (such as Ministries of Education) are also developing high level overarching competencies that are not directly connected to a field of study. These frameworks tend to focus on broad and transferrable competencies that they are looking to develop in all students that will ultimately serve them well long after graduation, regardless of their career path.

This wide range of uses strengthens the case for competency frameworks to be open and accessible. Competencies span job roles, occupations and sectors, and development cycles for competency frameworks have different drivers. By collaborating and sharing our insights, we make the development and revision of competencies over time easier for everyone and give people the freedom to revisit and revise similar competencies to meet their specific needs and use cases.

Let’s preface this by saying that there are many different reasons and uses for competency frameworks, as outlined in the previous chapter, and there are multiple ways to build a framework depending on its ultimate purpose. At a minimum, if you have a number of competencies and some form of organization or structure, you have a competency framework but each component within the framework has a specific purpose. These components include, but are not limited to:

These are the fundamental building blocks of any competency framework. We talked earlier about the importance of defining competencies and what the different parts of a competency description do. Competencies themselves form the basis for evaluation and inform learning and training needs; however, without a defined structure and organization competencies are limited in how effectively they can be used. Imagine a pile of building materials without any plans, and you have an analogy for competencies without structures.

In order to make individual competencies particularly useful to the end user, they need to be organized in a logical fashion. We’ll talk more about grouping and clustering competencies in the next chapter, but structures and hierarchies may include:

In addition to structures and hierarchies, connections between competencies, assessments and training/learning are important in creating holistic assessment and determining learning/training requirements. Connections between similar competencies either in the same framework or in a different framework create pathways for career progression and transferability. As an example, a competency about working safely in one industry sector or occupation could be linked to a similar competency in a different occupation or sector, and include information about any gap training or up-skilling required due to difference in scope or application.

The grouping and clustering of competencies can take a variety of forms, and often this is done according to an occupation or a job role. That is not to say that there is only one way to cluster groups of competencies, and creating structures that allow for competencies to be applied across different industries, occupations, and roles is important when designing a common competency framework. Competencies and groups of competencies can also be used for the purposes of designing training and credentialing, which may or may not align directly with the needs of a specific workplace, occupation, or sector.

Some different approaches that are commonly used include:

There is no universal approach to grouping competencies, and most large frameworks will have competencies categorized in multiple ways. For example, a framework for an occupation may also break down the competencies used in that occupation according to themes or groupings of related competencies. Large competency frameworks often rely on the use of metadata such as keywords and tags to cross-reference information, but also rely on technology such as a web-based interface connected to a database or library of competencies. What becomes increasingly important, especially the larger a framework, is that the information can be tracked and managed effectively, and that individual competencies are viewed as building blocks for larger structures.

To understand how competencies act as a building blocks, think of the difference between a jigsaw puzzle and a Lego® set. Both are comprised of pieces that are designed to fit together to form a larger whole, but a jigsaw puzzle only has one possible combination. A Lego® set, even if purchased to assemble a specific project, has pieces that can be disassembled and rearranged in an infinite number of ways to form new structures.

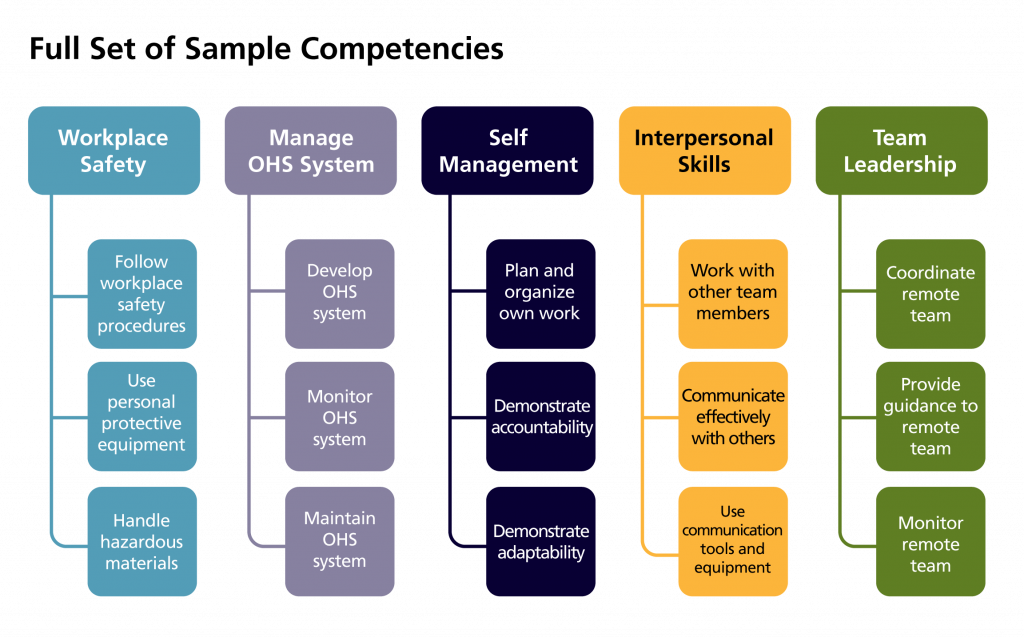

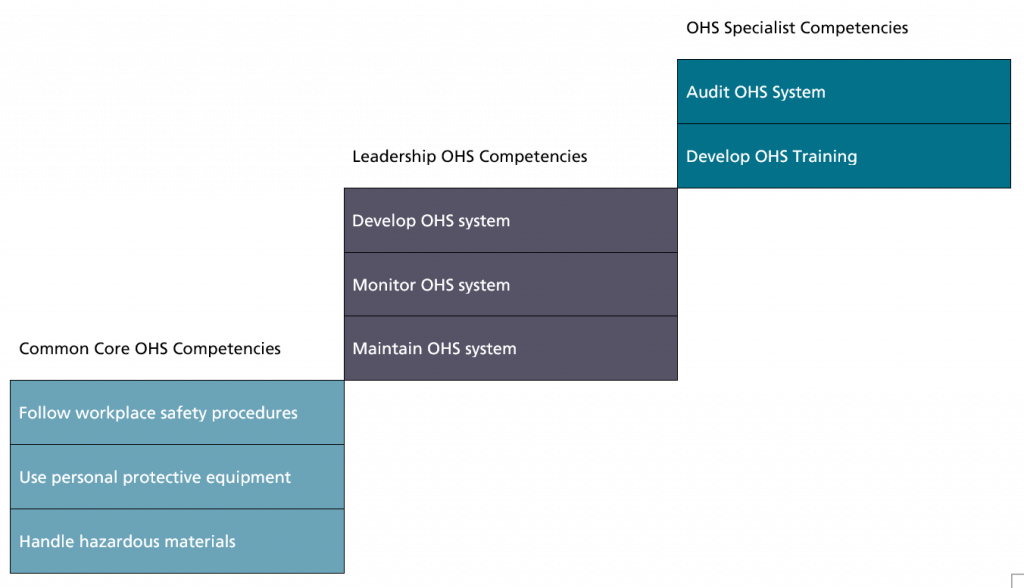

Here is an example of related competencies, and how they can be viewed as a group covering one topic; a larger group with subdivisions for multiple topics; as a group split into two separate competency units aligned with different roles and levels of responsibility; or as an individual competency. This group of competencies, arranged by theme, might apply to multiple job roles or to an occupation or sector as well.

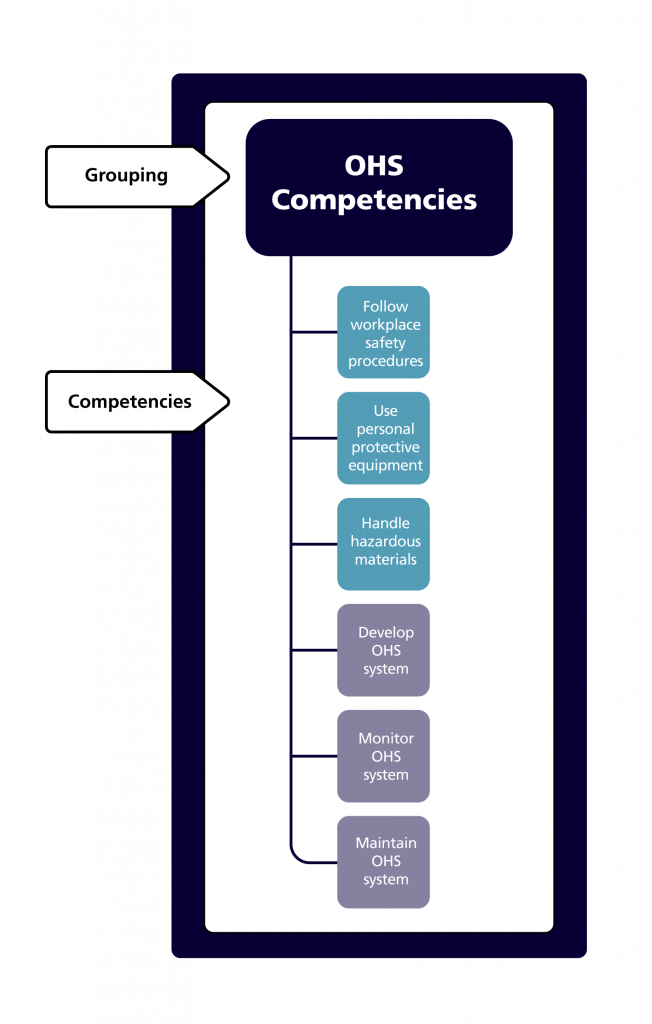

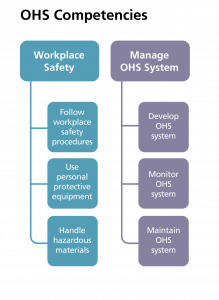

This example shows all of the workplace safety competencies within a framework.

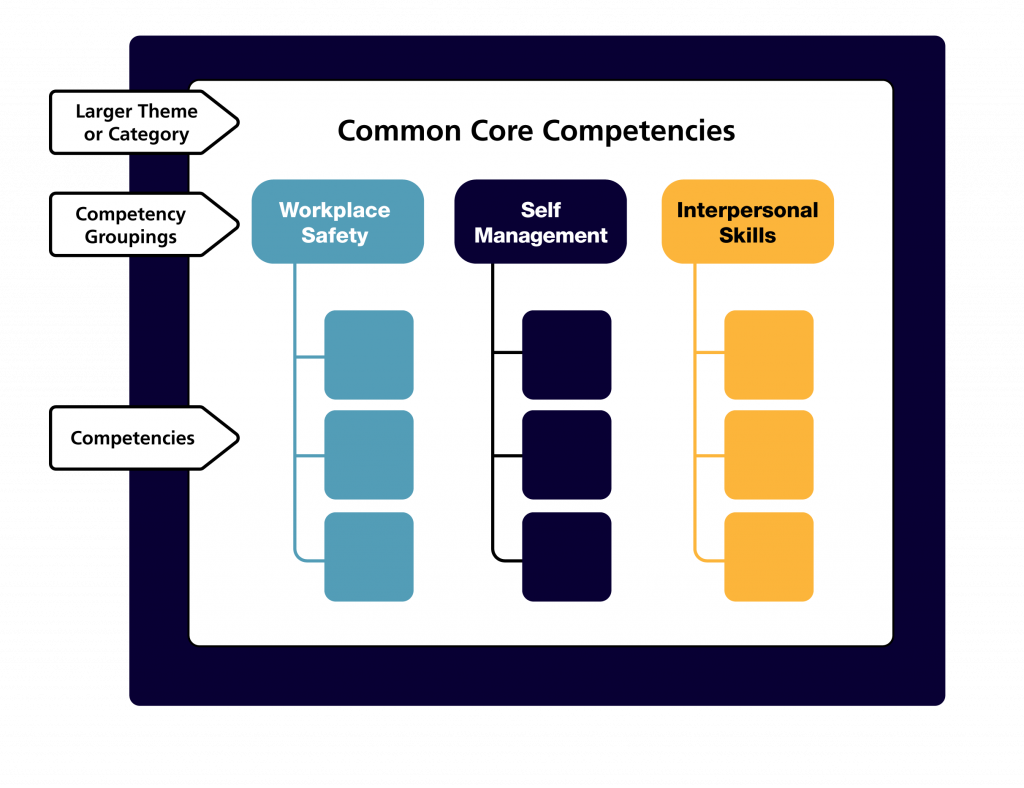

This example shows how the Workplace Safety competencies might be a part of a larger category or theme within a framework, such as common core competencies that all workers must have, regardless of job role or occupation.

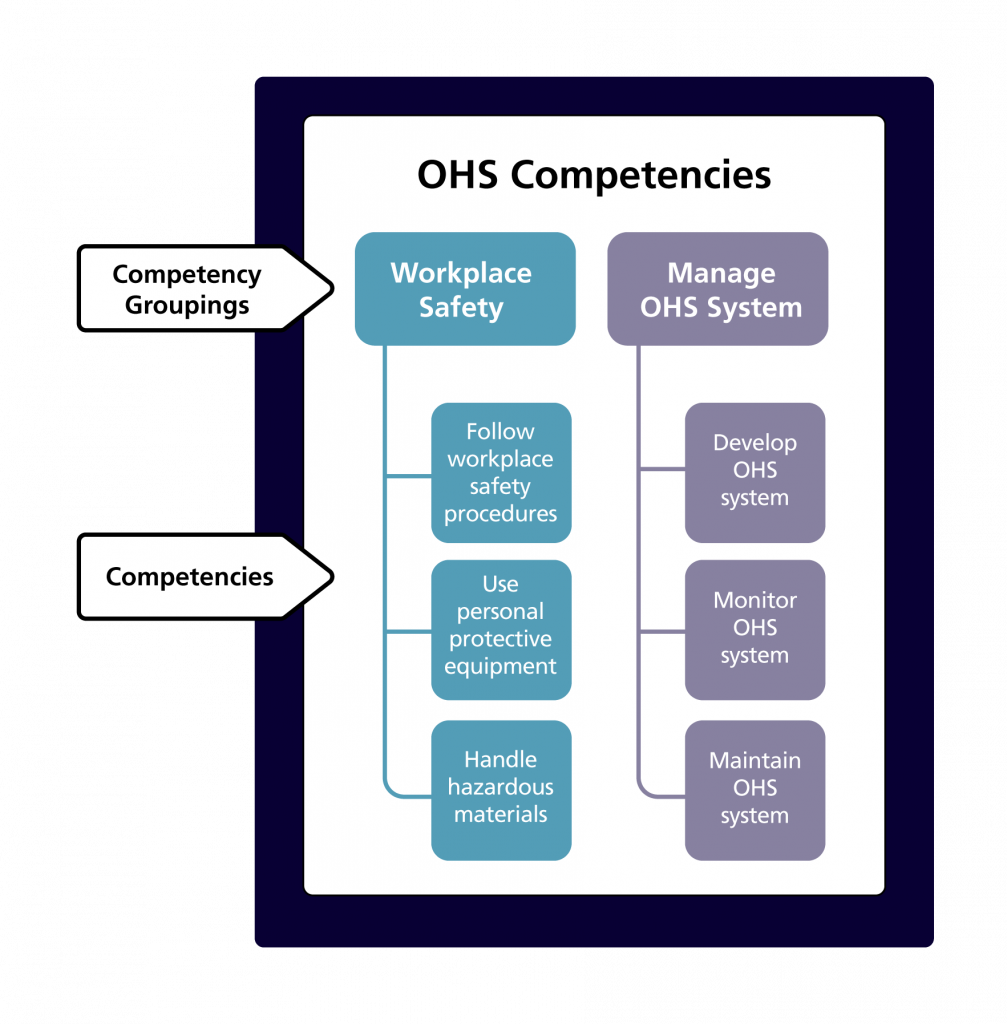

This example separates out the workplace safety competencies that apply to all workers, and those that may only apply to managers and others responsible for the workplace’s safety system.

Here’s an example of one competency from the previous list in detail, including the expected behaviours (performance criteria), supporting knowledge and skills, and some key terms and definitions.

Descriptions of context with accompanying examples may appear in a framework as additional information about a group of competencies or a specific competency, depending on the structure and intended use of the framework. This can be helpful in highlighting how the competencies are applied in the real world, identify any new and emerging trends, or to help those in designing realistic ways to assess the competency or group of competencies. For example, safety competencies are often evaluated in conjunction with other activities, as they are used regularly and for a number of different tasks.

Examples:

(This applies to the whole group of workplace safety competencies.)

(These apply specifically to using hazardous materials.)

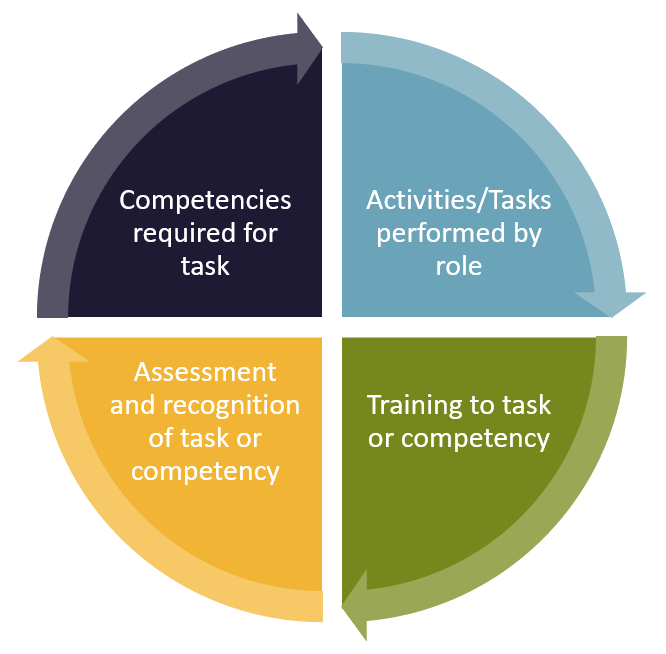

In this section, we’ll look closer at how competencies are used within a framework. We’ll start with some specific use cases and examples, and then look at how these relate to the broad uses we discussed in the first section.

Workforce development: relating competencies to job roles, activities and tasks

Training and learning: relating competencies to formal and informal learning activities

Assessment: relating competencies to evaluation of performance

There are many use cases for competency frameworks, which will determine how you go about creating or adapting your framework. We have identified some different use cases to give you an idea of how people use competency frameworks. We framed these use cases by asking the following questions:

Who will be using the toolkit?

What problem are they trying to solve?

What context will they be using it for?

How will this help?

The examples in the following pages illustrate how a competency framework can be used for a variety of applications. We will be relating them to the four major themes we identified earlier.

| Context | Use |

| Training and Learning | Developing individuals and teams through teaching and learning activities |

| Assessment | Evaluating individual and team performance in formal and informal ways |

| Credentialing | Recognizing achievements and issuing records of achievement |

| Workforce Development | Identifying individual, organizational and sectoral needs, career planning, and managing talent |

These of course, are interrelated, as competencies relate to job roles and work activities/tasks, training, and assessment.

High level context: Job roles are generally defined around assigned tasks and activities, and therefore, the competencies required to perform in the role. These may be used to recruit people with the competencies required for a certain role, to identify emerging skill needs, and to coordinate ongoing talent management such as career growth and succession planning.

Examples:

Who: Employer

What problem: The organization has grown and it’s difficult to describe and evaluate job roles and performance expectations across departments.

What context: I would like to develop a set of defined competencies that everyone in the organization needs to address all the tasks involved. Also, competencies specific to job roles and work activities are required.

This will help: By providing templates and resources to help us develop these competencies internally, using vetted and validated approaches

Who: Industry group in an emerging field

What problem: There is no consistent and validated information on the occupations in our emerging field, making it difficult to convey our workforce development needs

What context: I would like to develop a set of defined competencies and typical job roles/occupations in our field so that there is consistency across the industry

This will help: By providing a validated approach to developing competencies and competency frameworks, we will define our occupations in a way that has been developed and reviewed by national contributors

Both of these use cases focus on developing competencies in relation to activities and tasks in the workplace. To help you define the competencies required for an activity or task it’s important to understand the difference between the two.

Task and activities both require competencies to perform or complete them, but generally speaking:

This understanding of the relationship between competencies and activities and tasks is important when it comes to creating competencies. To determine the competencies required to perform an activity, you need to watch or speak with someone who knows how to complete the activity. Normally, the person(s) will show you (or outline) a set of tasks that are needed to complete the activity. At this point, you will be able to start identifying the competencies (e.g. knowledge, skills and attributes) that are required to successfully complete the activity.

You will probably find that many of the tasks that you identify will also help you to determine how to assess the performance and determine any training requirements. This helps to frame your competencies.

Let’s look at an activity that many of us do every day – prepare and serve a meal.

Preparing a meal is an activity, which may include several tasks:

What are the competencies we need in order to complete this activity? Preparing a meal is not a competency, but it does draw on certain competencies that apply to all cooking and/or baking activities:

Process for creating competencies related to work activities::

High level context: Competencies provide clear definitions of expected performance, and therefore can be used to inform the training and learning needs of individuals, teams, and organizations. Training and learning may be formal, such as structured courses and programs of study, or informal, such as a personal development plan in the workplace.

Examples:

Who: College or university teams (curriculum developers, teaching and learning centres, faculty, continuing education leaders, Deans)

What problem: We have heard that we need to incorporate competencies into our programming, but don’t know what that means.

What context: Hoping to build competencies into new programming, or approach existing programming with a competency lens to “uncover” latent competencies that may be eligible to turn into micro-learning opportunities.

This will help: By providing a baseline of information to understand how to identify and speak about a competency vs. a learning outcome.

Who: Employer (e.g. HR department, Managers, Executives)

What problem: We need to connect ongoing professional development to our organization’s needs and job roles.

What context: I would like to develop a professional development framework for all of our employees that can link the competencies we need with both internal and external training.

This will help: By providing a validated process to align competencies with formal learning and training needs.

If you are working in the training and learning sector, you might have been challenged with trying to explain the difference between a competency and learning outcome. Learning outcomes relate closely to competencies and often sound very similar. However, there are two major distinctions.

Learning outcomes may encompass one or many competencies in order to achieve the outcome and the competencies may be repeated in multiple contexts. For example, developing competence in problem-solving may be carried out over a number of courses associated with various learning outcomes.

Process:

If no formal learning is required:

If formal learning is required:

A few questions to consider for formal learning:

If the learning activities and outcomes are designed as a component of developing underlying skills and/or knowledge, but will not result in the ability to demonstrate all of the performance criteria for the competency, then any criteria that need to be developed externally should be identified.

The Learning Design Canvas in the Templates section is a helpful tool to get you started.

High level context: Assessing competencies is critical when determining performance proficiency. It’s important to ensure that competencies are being measured in context with the activities and tasks that require them, and by the individuals and teams using them.

Examples:

Who: Professional association or licensing body

What problem: Skill and competency profiles from different jurisdictions vary in both scope and language, making it difficult to assess similar credentials at face value.

What context: We are developing a framework for evaluating the skills of trained professionals from different jurisdictions against a consistent standard for practice.

This will help: By providing a consistent strategy to assess competence against a defined industry standard.

Who: Employer (e.g. HR department, Managers, Executives)

What problem: We need to connect ongoing professional development to our organization’s needs and job roles.

What context: I would like to integrate assessing competencies required for different roles into our ongoing performance management process.

This will help: By providing a validated process to align competencies with formal learning and training needs.

Assessment and evaluation have different contexts and meanings, depending who you ask. For some, assessment is formal, and evaluation is a more casual, ongoing activity, and for others it’s the reverse. In either case, competencies include supporting information (e.g. performance criteria), which form the basis for assessment, whether through a formal testing process, or through a combination of observation, reflection, and feedback.

What is critical in determining assessment approaches are ensuring:

Process:

This toolkit is not intended to specifically provide guidance in the development of formal assessments, but since assessment may be an intended use of your competency framework it bears mentioning a bit about using proficiency scales and rubrics here.

Proficiency scales and rubrics are key to formal assessment of competencies. Because much of determining competence is related to observing real-world performance, it is important to do everything possible to remove subjectivity from the assessment process.

Proficiency scales set out the range of assessment. They can be very simple – such as a competent/not competent or pass/fail approach, or have multiple levels such as the typical “beginner to expert” scale illustrated earlier. Some assessment approaches will use a numerical scale (e.g. from 1-5 or 1-10, or a percentage), but in any case a rubric is necessary to set the criteria for those doing the assessment. The type of scale usually is linked to the nature of the competency – for example, the assessment of competencies related to safety and high-risk activities often have a binary pass/fail scale attached. You either work safely or you don’t, and there may be a specific threshold that needs to be met to ensure the safety of everyone.

Rubrics specify how to assign a rating to the proficiency scale. For a binary pass/fail they should be specific enough to identify and clarify what was or was not demonstrated during the assessment in order to achieve the result, and for a scale with multiple levels, detail the criteria specific to the attainment of each level. Rubrics are also helpful for people using competency frameworks for ongoing professional development or performance reviews, as they provide detailed information about what is expected.

High level context: Recognizing achievement of competencies is an integral piece of many occupational designations and ongoing professional development.

Examples:

Who: Professional association or licensing body

What problem: Skill and competency profiles from different jurisdictions vary in both scope and language, making it difficult to compare similar credentials.

What context: We need to ensure that those working in our profession have a consistent set of competencies in order to practice professionally.

This will help: By providing a validated approach and structure for developing a competency framework that is linked to both formal credentials and ongoing professional development needs.

Who: College or university teams (curriculum developers, teaching and learning centres, faculty, continuing education leaders, Deans)

What problem: We don’t know how to map our competencies together and how to categorize them in a way that will make sense to grant administrators.

What context: Preparing a grant application to develop multiple micro-credentials that ladder into regular programming.

This will help: By providing a structure to map existing competencies to and demonstrate relationships between them.

A common use for competency frameworks is in defining and relating competencies to licensing requirements and professional designations, which include both formal credentials (such as those issued by a college/university, or regulatory body) and required ongoing professional development (such as endorsements or micro-credentials).

Stucturally, this use of a competency framework is based on workplace and job roles, but the linkages to credentials may vary greatly. In some cases, there are prerequisite educational requirements or credentials that precede entry into an occupation, and these may not necessarily be captured in the competency framework. In other cases, entry to practice has no formal credential requirement, and competencies are developed through a combination of formal learning and on-the job experience.

How competencies are applied in both of these situations are similar, in that there are generally a set of common competencies that apply to a range of activities, or include behaviours expected across the occupation. There is also a work activity/task based structure that identifies the competencies used for different roles and areas of specialty, and in many cases there is a requirement for ongoing re-certification or licensing to ensure currency in the field is maintained.

Process:

High level context: There may be other uses for competency frameworks including uses for policy makers and others that are indirectly related to one of the main categories we have already mentioned. This includes the use of competency frameworks as a valuable research tool.

Examples:

Who: Funding body or agency

What problem: There is no authoritative source to refer my grant applicants to ensure that the applications I get back have a consistent definition and application of competency.

What context: I am developing a funding call for micro-credentials and I want them to all be competency based.

This will help: By providing an authoritative and vetted source of information on competencies that has been developed and reviewed by national contributors.

Who: Student or job seeker

What problem: There is an overwhelming amount information being presented to me about career options and I don’t know where to get a real understanding of different careers.

What context: I would like to know which careers align best with my skills and interests

This will help: By providing clarity on how to interpret competency frameworks and other sets of occupational standards that have similar structure.

Competency frameworks contain valuable information about work activities, the required skills, knowledge and attributes, and educational requirements of different occupations and sectors. Competency frameworks can also be very confusing to interpret, and understanding how they are constructed can help to demystify them.

This section is dedicated to those who are tasked with creating competency frameworks. It includes some guidelines and best practices, as well as more detailed information on how to use and adapt the templates and samples provided to support your development (or evolution) of a competency framework.

Adapting an existing framework

Sample competency framework structures

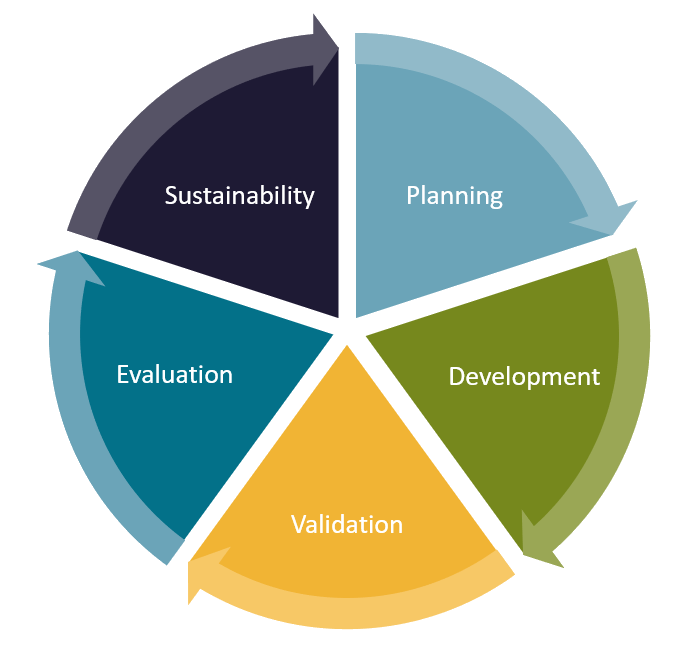

Whether you are planning the development of a brand new competency framework or looking to use the toolkit to update or revise an existing one, there is a recommended process and considerations to ensure that you get the most out of your effort. We will look at these a little further from two points of view in the next chapters:

Whether you are creating or revising a competency framework, the process is much the same. However, for each stage there will be more or less emphasis on certain activities depending on your context.

Below is an outline for the overall process of developing a competency framework.

(Click on each process step heading to show/hide the details for that step)

Templates for this stage: Competency Framework Development Canvas

Included in this stage:

Important considerations at this stage:

Templates for this stage: Competency Authoring Template and Competency Framework Development Workbook

Included in this stage:

Important considerations at this stage:

Included in this stage:

Important considerations at this stage:

Included in this stage:

Important considerations at this stage:

Included in this stage:

Important considerations at this stage:

Perhaps your competency framework is due for revision, or you have had some feedback that your current format is not meeting the needs of some of your users. Whatever the case may be, you can use this toolkit and the templates as a resource to plan and revise an existing framework.

(Click on each process step heading to show/hide the details for that step)

Templates for this stage: Competency Framework Development Canvas

Main activities at this stage:

Important considerations at this stage:

Templates for this stage: Competency Authoring Template and Competency Framework Development Workbook

Main activities at this stage:

Important considerations at this stage:

Main activities at this stage:

Important considerations at this stage:

Main activities at this stage:

If you are building a new competency framework, you are likely not creating everything from scratch. There may be some existing information to draw from, but the toolkit can help you work through the process and provide templates for different stages of the process.

(Click on each process step heading to show/hide the details for that step)

Templates for this stage: Competency Framework Development Canvas

Main activities at this stage:

Important considerations at this stage:

Templates for this stage: Competency Authoring Template and Competency Framework Development Workbook

Main activities at this stage:

Important considerations at this stage:

Main activities at this stage:

Important considerations at this stage:

Main activities at this stage:

Important considerations at this stage:

This section provides some sample competencies that have been created using the templates in the toolkit. We have selected five categories of competencies to illustrate the following:

The sample competencies are listed under each of five categories (or specific areas of competency) listed below:

The sample competencies listed on this page may be downloaded for you to use and/or adapt for your specific purpose. Feel free to download each competency and adapt it to suit your purpose(s).

Click here to download all of the examples and templates in one folder. (Link opens in new tab)

Suggestions for editing/customizing the examples:

Every workplace has requirements for health and safety. While the context and level of risk changes by work environment and job role, these competencies should be applicable in most workplaces. A list of sample competencies follows below and have been categorized based on common core and supervisory contexts. Click on the link to each competency for an example of how it has been defined using the competency template in this toolkit.

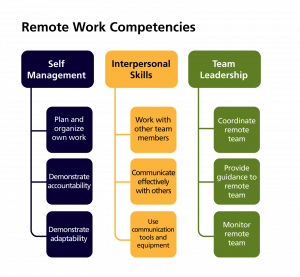

This set builds on many competencies that apply to many workplaces, but the recent pandemic and resulting changes in how we have worked have heightened certain competencies.

The COVID-19 pandemic has forced many people to change the way they work. For many, working remotely is now the norm resulting in the need to transfer skills to complete work tasks from afar. The sample competencies outlined in this section can be applied to any work context; however, they may be applied in a new way given the demands of working remotely. For example, the use of communication equipment and technology has dramatically increased for some people, as has the increased focus on accountability and adaptability. For leaders, managing a team remotely has meant developing new ways to approach work and to keep people engaged while remaining productive.

Common Core Competencies (apply to everyone)

Common Core Competencies (apply to everyone)

Competency framework structures can vary from the very simple to the extremely complex. There is no one way to create a competency framework structure; however, there are better structures than others depending on the intended use. When developing the framework structure, it’s important to consider the purpose and the users of the framework. Does the framework need to be simple in structure for people to use and/or understand? Or do you need to develop a more complex structure to fulfill all the requirements of the intended uses?

Managing information, especially a lot of complex information is critical to making a competency framework useful. Most frameworks will have a defining structure or taxonomy that organizes competencies (and other information as well) from broad groupings into more and more specific groupings. Depending on the framework there may be multiple taxonomies, each with its own purpose. At a minimum, individual competencies should be grouped in a logical manner, and in a way that makes the information easy to find and organize.

Examples of Taxonomies:

Competencies sorted into categories using a structured taxonomy:

Specific Example (Culinary Arts Framework)

Typically, each of the groupings should be logical and manageable. 3-5 competencies in a specific area of competency, and 3-5 SACs in a GAC are a good rule of thumb. If you only have 1 or 2 , then look at how these might be combined with other groupings. If you have 6 or more, consider how they might be divided.

Another way that taxonomies are found in a framework are those organized by work activity or job role/position. Similarly, these may have sub structures.

Taxonomy Example | Specific Example |

By work activity

| Carpentry

|

By occupation

| Medical Occupations

|

By organization

| Large Organization

|

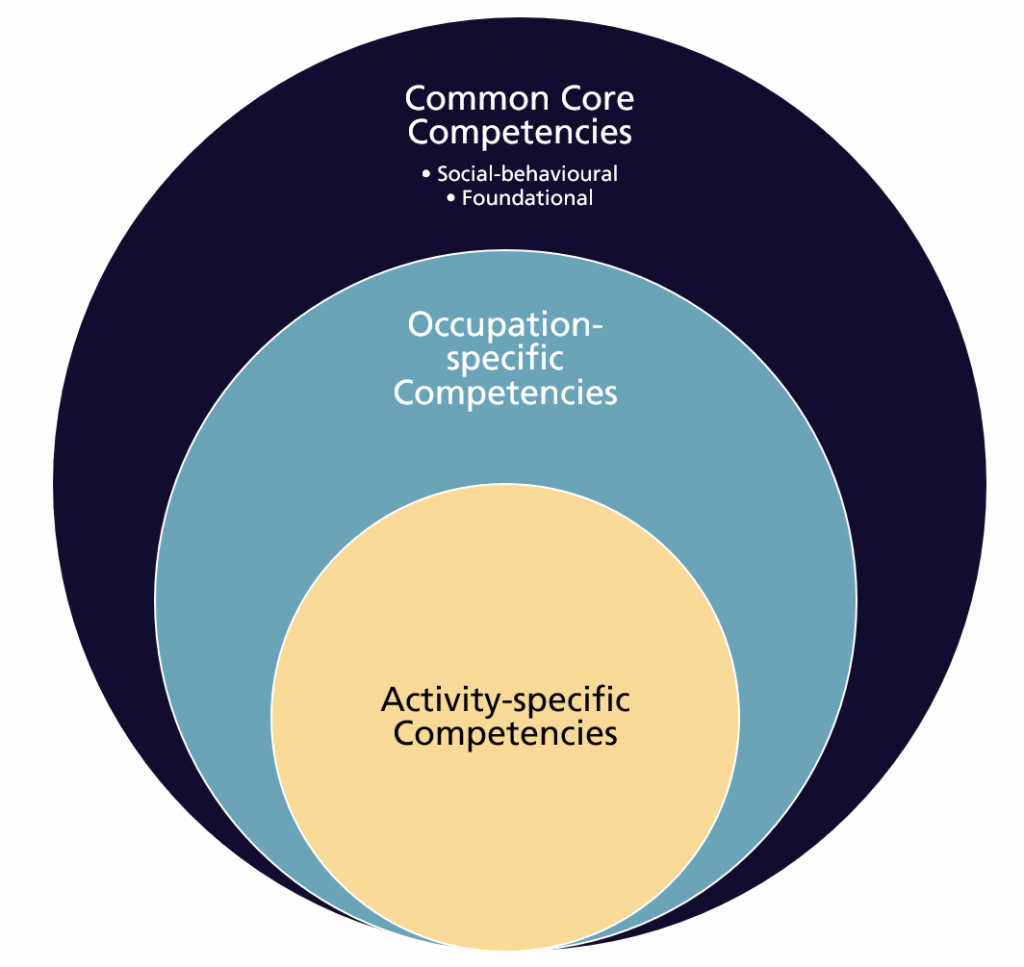

Many frameworks have a set of common core competencies (they might also be referred to as ‘foundational’ competencies) that might apply to a broad range of occupations, job roles, or activities. These often include things like Health and Safety or Interpersonal Skills and may be coupled with requirements for on-boarding or pre-employment training, or tie into well-defined sets of employability skills or essential skills.

Some common core competencies may not be tied to specific occupations or activities. These competencies typically describe attitudes and values that must be used when undertaking any activity. Some people refer to these competencies as social-behavioural; for example, competencies that require a person to conduct activities with a specified attitude. These would be considered overarching to the rest of the occupation-specific or activity-specific competencies.

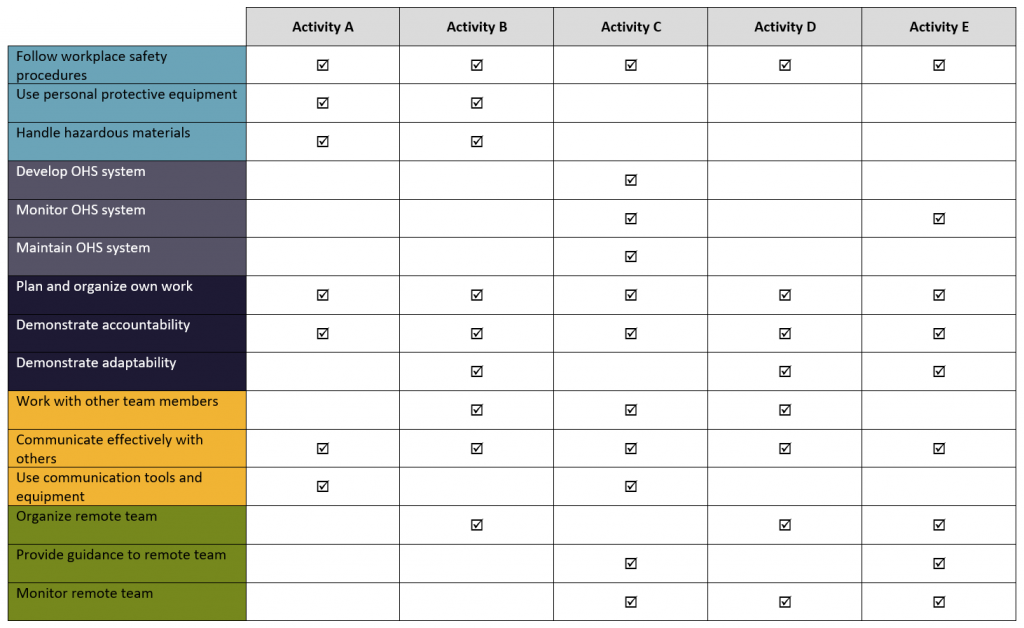

For many frameworks, particularly those linked to occupational performance, there is a need to provide a distinction between the work activities being performed and the competencies that support them. For these, there tends to be a matrix approach where the activities (and tasks that are required to complete the activities) are cross-referenced to a set of competencies. Within this type of structure, the competencies may also have their own hierarchy and groupings. In a framework that contains such a structure, assessments and learning are often aligned with the activities, as opposed to the competencies. Mapping the competencies to the activities will help you identify logical groupings that will help build your competency framework.

Within a group of competencies, there may be relationships that structure some competencies as more advanced, or requiring other competencies as prerequisites. For example, many leadership or supervisory competencies build on foundational competencies or those required for a certain activity. In this example, one must have all of the workplace safety competencies in order to manage the OHS system for the workplace. There may even be additional more advance competencies that only relate to OHS specialists, such as auditing and developing training.

Here are some examples of existing frameworks that use some or all of these structures.

ESDC Skills and Competencies Taxonomy

Essential Competencies for Midwifery Practice

Toronto Region Immigrant Employment Council’s Inclusive Workplace Competencies

IT Professionalism Europe’s e-CF Explorer

European Skills/Competences, qualifications, and Occupations (ESCO)

Ok, so now that you have all of your competencies defined, how do you turn all of that into a completed framework? In order to make a framework usable it needs to contain all of the information necessary for the end users, and be presented in away that it is understood by them as well.

Most frameworks, particularly if there will be a print (or digital downloadable) version available will have some introductory material. Web-based frameworks will generally have a landing page or pages with the same information.

This should include:

This is the main content of the framework.

This should include:

Depending on the complexity of the framework, you may decide to aggregate some common information from competency groupings, such as supporting knowledge and skills that apply to multiple competencies, or context in how a group of competencies is utilized. The goal is clarity and presenting the framework is a way that the end user can access and understand the information easily and for their intended purpose.

Appendices are a good way to store aggregated information that applies to the framework as a whole.

This might include:

Click here to download all of the examples and templates in one folder. (Link opens in new tab)

Individual templates and their uses are identified below:

Competency Framework Development Canvas

What it is: This tool is useful for planning a competency framework, by capturing the intended audience, as well as information you need to develop and maintain your framework

Learning Design Canvas (with instructions)

What it is: A version of the development canvas tool can also be used to design learning, either to go with a competency framework or independently

Competency Authoring Template (blank)

Competency Authoring Template (with instructions)

What it is: This template includes all the fields used for the sample competencies. The version with instructions has some annotations about what to put in each field, and the blank versions is there for you to populate. In practice, it’s easiest to use this template to detail specifics for each competency, and use the workbook below to provide a high level overview of the framework and look for overlap or duplication.

Open Competency Framework Development Workbook

What it is: These spreadsheets allow you to to capture the information about all of your competencies and your framework structure in one place.

Something that an individual or team undertakes effort to complete. Activities may be broad and ongoing, or may require a number of specific tasks, each of which may have its own beginning and end.

The ability to do something successfully or efficiently

The specific and measurable combination of knowledge, skills and attributes that result in the performance of an activity or task to a defined level of expectation or performance standard.

A combination of well defined competencies and hierarchical information on how competencies are grouped and connected to work activities, job roles, assessments and more for various applications.

A set of more than one defined competencies that create a larger component within a competency framework or for a particular use. Competency groupings may be hierarchical and have several layers of sub-groupings, and a single competency may be included in many different groupings.

A descriptive statement that states what a competent individual is doing, and in what context

Concrete action verbs are also known as measurable verbs. They state actions which can be observed and measured when used in context with an activity.

A digital badge is a digitally issued credential that contains structured information that is standardized for easier sharing and can be evaluated and authenticated via embedded links. This leads to trusted recognition for learners and makes their credentials more portable and meaningful.

measurable and observable actions that demonstrate performance of the competency to the expected standard

Learning activities are the things the learner engages in doing to achieve the learning objectives. Learning activities may be lessons, assignments, projects, etc. and may or may not be graded or assessed.

Learning objectives are smaller and more focused than learning outcomes. They state the intended goals for smaller pieces of learning, such as for a single lesson or course module. (e.g. Each lesson in a course will have specific learning objectives.) Objectives usually focus on knowledge acquisition or development of discrete skills; describe process rather than the intended result and are aligned with learning outcomes.

Learning outcomes are broad statements of what someone will be able to do on completion of the learning intervention, usually at the end of a "course" or "program". The learning outcome expresses the integrated learning by a student and explains what the learner will achieve.

Metadata is data that describes or summarizes other data. It provides information about a certain item's content. This may include tags or key words that are attached to a descriptor and therefore can by searched, found easily and are machine readable.

A micro-credential is a certification of assessed learning associated with a specific and relevant skill or competency. Micro-credentials enable rapid retraining and augment traditional education through pathways into regular postsecondary programming.

measurable outcomes required to demonstrate proficiency in the competency

A system for measuring levels of proficiency. Proficiency scales may have a number of defined steps or stages or may be expressed in terms of a percentage compared to the highest level of performance. Proficiency scales are often used for formal assessment of practical tasks, when combined with defined performance criteria and rubrics.

Specifications for grading against a specific scale. Rubrics in the context of assessment of competence should identify specific specific performance that must be demonstrated in order to be granted a specific status or level of achievement in relation to the competency and/or proficiency scale.

The underlying things you must know and be able to do in order to demonstrate the competency. Knowledge and skills alone are not enough to demonstrate competence; they must be applied together within the context of the activity being undertaken.

A specific activity that has a start and an end. Multiple tasks may be required to complete broader work activities, and tasks may in turn have smaller sub-tasks or steps that are required to complete them.

A classification into ordered categories. In competency frameworks, it usually refers to information categorized and arranged in several, increasingly specific levels.

The world of work and learning encompasses activities and expectations that are found in both the workforce and higher education, as well as those that may be done on a volunteer basis but include clear roles, responsibilities, and performance expectations.

Here is a summary of external links found in the toolkit and some that may be helpful for additional reference.

eCampusOntario’s Micro-Credential Principles and Framework

ESDC Skills and Competencies Taxonomy

US Department of Labour’s O*Net Portal

European Skills/Competences, qualifications, and Occupations (ESCO)

Australian Training and Qualifications Framework

New Zealand Qualifications Framework

South African Qualifications Authority

Essential Competencies for Midwifery Practice

Toronto Region Immigrant Employment Council’s Inclusive Workplace Competencies

IT Professionalism Europe’s e-CF Explorer

T3 Innovation Network Learning and Employment Records (LER) Hub

Canada’s Essential Skills (ESDC)

Ontario’s Essential Employability Skills