1

Pulling Together: A Guide for Researchers, Hiłḵ̓ala by Dianne Biin, Deborah Canada, John Chenoweth, and Lou-ann Neel is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

The CC licence permits you to retain, reuse, copy, redistribute, and revise this book—in whole or in part—for free for non-commercial purposes providing the author is attributed as follows:

If you redistribute all or part of this book, it is recommended the following statement be added to the copyright page so readers can access the original book at no cost:

Sample APA-style citation (7th Edition):

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-77420-101-5

Print ISBN: 978-1-77420-100-8

Cover image attribution:

Inspired by the annual gathering of ocean-going canoes through Tribal Journeys, Pulling Together, created by Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw artist Lou-ann Neel, is intended to represent the connections each of us has to our respective Nations and to one another as we Pull Together. Working toward our common visions, we move forward in sync so we can continue to build and manifest strong, healthy communities with foundations rooted in our ancient ways.

Thank you to all of the writers and contributors to the guides. We asked writers to share a phrase from their Indigenous languages on paddling or pulling together…

‘alhgoh ts’ut’o ~ Wicēhtowin ~

kən limt p cyʕap ~ si’sixwanuxw ~ ƛihšƛ ~

Alh ka net tsa doh ~ snuhwulh ~

Hilzaqz as q̓íǧuála q̓úsa m̓ánáǧuala wíw̓úyalax̌sṃ ~

k’idéin át has jeewli.àat ~ Na’tsa’maht ~

S’yat kii ga goot’deem ~ Yequx deni nanadin ~

Mamook isick

Thank you to the Indigenization Project Steering Committee, project advisors, and BCcampus staff who offered their precious time and energy to guide this project. Your expertise, gifts, and generosity were deeply appreciated.

Verna Billy-Minnabarriet, Nicola Valley Institute of Technology

Jo Chrona, First Nations Education Steering Committee

Marlene Erickson, College of New Caledonia, BC Aboriginal Post-Secondary Coordinators

Jan Hare, University of British Columbia

Colleen Hodgson, Métis Nation British Columbia

Deborah Hull, project co-chair, Ministry of Advanced Education and Skills Training

Janice Simcoe, project co-chair, Camosun College, I-LEAD

Kory Wilson, British Columbia Institute of Technology

Dianne Biin, project manager and content developer

Michelle Glubke, senior manager

Lucas Wright, open education advisor

|  |

Dedicated to Dr. Deborah Canada, who was a Métis–Swampy Cree researcher and educator and dean of Academic Programs at Nicola Valley Institute of Technology.

BCcampus Open Education believes that education must be available to everyone. This means supporting the creation of free, open, and accessible educational resources. We are actively committed to increasing the accessibility and usability of the textbooks we produce.

The web version of this resource has been designed to meet Web Content Accessibility Guidelines 2.0, level AA. In addition, it follows all guidelines in Appendix A: Checklist for Accessibility of the Accessibility Toolkit – 2nd Edition. It includes:

| Element | Requirements | Pass? |

|---|---|---|

| Headings | Content is organized under headings and subheadings that are used sequentially. | Yes |

| Images | Images that convey information include alternative text descriptions. These descriptions are provided in the alt text field, in the surrounding text, or linked to as a long description. | Yes |

| Images | Images and text do not rely on colour to convey information. | Yes |

| Images | Images that are purely decorative or are already described in the surrounding text contain empty alternative text descriptions. (Descriptive text is unnecessary if the image doesn’t convey contextual content information.) | Yes |

| Tables | Tables include row and/or column headers that have the correct scope assigned. | Yes |

| Tables | Tables include a title or caption. | Yes |

| Tables | Tables do not have merged or split cells. | Yes |

| Tables | Tables have adequate cell padding. | Yes |

| Links | The link text describes the destination of the link. | Yes |

| Links | Links do not open new windows or tabs. If they do, a textual reference is included in the link text. | Yes |

| Links | Links to files include the file type in the link text. | Yes |

| Audio | All audio content includes a transcript that includes all speech content and relevant descriptions of non-speach audio and speaker names/headings where necessary. | N/A |

| Video | All videos include high-quality (i.e., not machine generated) captions of all speech content and relevant non-speech content. | N/A |

| Video | All videos with contextual visuals (graphs, charts, etc.) are described audibly in the video. | N/A |

| H5P | All H5P activities have plain text alternatives. | Yes |

| H5P | All H5P activities that include images, videos, and/or audio content meet the accessibility requirements for those media types. | N/A |

| Formulas | Formulas have been created using LaTeX and are rendered with MathJax. | N/A |

| Formulas | If LaTeX is not an option, formulas are images with alternative text descriptions. | N/A |

| Font | Font size is 12 point or higher for body text. | Yes |

| Font | Font size is 9 point for footnotes or endnotes. | Yes |

| Font | Font size can be zoomed to 200% in the webbook or eBook formats. | Yes |

While the guide itself meets accessibility guidelines, it links to a number of external resources that may not. This includes websites, PDFs, and videos that only have automatically generated captions.

We are always looking for ways to make our textbooks more accessible. If you have problems accessing this textbook, please contact us to let us know so we can fix the issue.

Please include the following information:

You can contact us one of the following ways:

This statement was last updated on April 23, 2021.

The Accessibility Checklist table was adapted from one originally created by the Rebus Community and shared under a CC BY 4.0 License.

This resource is available in the following formats:

You can access the online webbook and download any of the formats for free here: Pulling Together: A Guide for Researchers, Hiłḵ̓ala. To download the book in a different format, look for the “Download this book” drop-down menu and select the file type you want.

| Format | Internet required? | Device | Required apps | Accessibility Features | Screen reader compatible |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Online webbook | Yes | Computer, tablet, phone | An Internet browser (Chrome, Firefox, Edge, or Safari) | WCAG 2.0 AA compliant, option to enlarge text, and compatible with browser text-to-speech tools, videos with captions | Yes |

| No | Computer, print copy | Adobe Reader (for reading on a computer) or a printer | Ability to highlight and annotate the text. If reading on the computer, you can zoom in. | Unsure | |

| EPUB and MOBI | No | Computer, tablet, phone | Kindle app (MOBI) or eReader app (EPUB) | Option to enlarge text, change font style, size, and colour. | Unsure |

| HTML | No | Computer, tablet, phone | An Internet browser (Chrome, Firefox, Edge, or Safari) | WCAG 2.0 AA compliant and compatible with browser text-to-speech tools. | Yes |

The webbook includes three interactive H5P activities. If you are not using the webbook to access this resource, this content will not be included. Instead, your copy of the text will provided a link to where you can access that content online.

However, the interactive activities are also provided in alternate formats for people not using the webbook. They have been made available in a static format in the Appendix A and B.

Even if you decide to use a PDF or a print copy to access the book, you can access the webbook and download any other formats at any time.

A Guide for Researchers is part of Pulling Together, an open professional learning series developed for staff across post-secondary institutions in British Columbia. Guides in the series include Foundations Guide; A Guide for Leaders and Administrators; A Guide for Curriculum Developers; A Guide for Teachers and Instructors; A Guide for Front-line Staff, Student Services, and Advisors; and A Guide for Researchers.

These guides are the result of the Indigenization Project, a collaboration between BCcampus and the Ministry of Advanced Education and Skills Training. The project was supported by a steering committee of Indigenous education leaders from B.C. universities, colleges, and institutes, the First Nations Education Steering Committee, the Indigenous Adult and Higher Learning Association, and Métis Nation British Columbia.

These guides are intended to support the systemic change occurring across post-secondary institutions through Indigenization, decolonization, and reconciliation. A guiding principle from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada process states why this change is happening.

Reconciliation requires constructive action on addressing the ongoing legacies of colonialism that have had destructive impacts on Aboriginal peoples’ education, cultures and languages, health, child welfare, the administration of justice, and economic opportunities and prosperity. (2015, p. 3)

We all have a role to play. As noted by Universities Canada, “[h]igher education offers great potential for reconciliation and a renewed relationship between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people in Canada” (2015). Similarly, Colleges and Institutes Canada notes that “Indigenous education will strengthen colleges’ and institutes’ contribution to improving the lives of learners and communities” (2015). These guides provide a way for all faculty and staff to Indigenize their practice in post-secondary education.

The Indigenization Project can be described as an evolving story of how diverse people can journey forward in a canoe (Figure 0.1). In Indigenous methodology, stories emphasize our relationships with our environment, with our communities, and with each other. To stay on course, we are guided by the stars in the sky, with each star a project principle: deliver holistically, learn from one another, work together, share strengths, value collaboration, deepen the learning, engage respectfully, and learn to work in discomfort. As we look ahead, we do not forget our past.

The canoe holds Indigenous people and the key people in post-secondary education whose roles support, lead, and build Indigenization. Our combined strengths give us balance and the ability to steer and paddle in unison as we sit side by side. The paddles are the open resources. As we learn to pull together, we understand that our shared knowledge makes us stronger and makes us one.

The perpetual motion and depth of water reflects the evolving process of Indigenization. Indigenization is relational and collaborative and involves various levels of transformation, from inclusion and integration to infusion of Indigenous perspectives and approaches in education. As we learn together, we ask new questions, so we continue our journey with curiosity and optimism, always looking for new stories to share.

We hope these guides support you in your learning journey. As open education resources, they can be adapted to fit local contexts, in collaboration with Indigenous Peoples who connect with and advise your institution. We expect that as more educators use and revise these guides, they will evolve over time.

A Guide for Researchers looks at systemic change of research by exploring research practice and process with Indigenous Peoples and knowledge. This change rests with researchers and teachers of research methods in post-secondary education. The Kwaḱwala term hiłḱala means one who is allowed or has permission. The term reflects a researcher’s responsibility and ongoing role in Indigenous research. While it takes a person a lifetime to develop into this role, it is not done alone: there are helpers, guides, and teachers along the way.

This guide is a helper for Indigenous and non-Indigenous researchers and those responsible for post-secondary research. You can use the guide in various ways:

This guide can be used as part of a learning community or in a group learning experience, adapting and augmenting it to include Indigenization pathways at your institution for Indigenous students and communities.

A Guide for Researchers is not a definitive resource, as First Nations, Métis, and Inuit perspectives and approaches are diverse across the province. We invite you to augment it with your own stories and examples and, where possible, include Indigenous voices and perspectives from your area in the materials.

To learn more about Indigenous-Canadian relationships since contact, please see the Foundations Guide.

Note: For a technical description of how to adapt this guide please see Appendix C: Adapting this Guide.

The following Indigenous faculty and advocates wrote this guide:

This guide was brainstormed and drafted during a weekend design retreat. As we got to know one another during the first day, we acknowledged the role that Indigenous leaders, matriarchs, and knowledge keepers have played to bring Indigenous research forward. They have maintained a standard of respect, integrity, honour, and trust when forging and building new relationships. Today, they help focus our work. The knowledge, protocols, and processes they share ensures collaborative research can rebuild our communities and create places where we stand together. We thank them for the teachings they provide us, as it gives us strength to work in spaces of resistance.

We also want to thank BCcampus and the Ministry of Advanced Education and Skills Training for providing this space to come together and share our experiences on Indigenous research and traditional knowledge protection with post-secondary institutions. We thank the research areas of these post-secondary institutions for their commitment and the good work they can do to assist with Indigenization and reconciliation.

A Guide for Researchers is intended for the following audiences and learners:

Each researcher approaches research with a different way of knowing, being, and doing. There is no one way of conducting Indigenized research, because it is based on place, relationships, and shared values.

To create a trusting relationship with Indigenous communities, researchers need to acknowledge the importance of using Indigenous language to build shared meaning. Gregory Cajete (2000), a Tewa scholar, stresses the importance of language to Indigenous Peoples: “Indigenous people are people of place, and the nature of place is embedded in their language” (p. 74). In British Columbia, there are 34 languages spoken across the province, as well as Michif and Chinook Jargon. This number does not include the many dialects of each language and language family, which are increasing as First Nations communities are reclaiming and revitalizing their language.

Almost all Indigenous languages have similar words or phrases that are used for proper introductions. Depending on the situation and context, introductions can either follow a formal protocol or be an everyday or common greeting. As we go through this resource together, let us begin by setting a context and building a dialogue. Gilakas’la is a Kwaḱwala phrase that translates in several ways depending on the context in which it is spoken. It can be a welcome or greeting, a form of engagement, or to give thanks, because it translates to “Come, breathe of the same air.” Inherent in understanding the meaning of Gilakas’la is knowing that we are coming together for some purpose. We tell each other our names, where we are from, and our family and ancestral lineage. After we announce our intentions and where we come from, we can then enter into a discussion to clarify the purpose we wish to embark upon together. In this same way, we see this guide as a form of introducing ourselves. Gilakas’la.

This section provides a brief background on ways research is evolving in Canada to be inclusive of, and responsible to, Indigenous voice, knowledge, and people. You will also see how recent institutional change processes are shaping how post-secondary institutions can support and lead changes in research processes.

Purpose of this section

This section looks at the various protocols and principles developed to bring Indigenous voice and expertise into collaborative research. Topics include:

This section can take up to 2 hours to complete on your own. Some group activities can occur over an academic semester.

Indigenous knowledge holders, wisdom keepers, Elders and scholars come to the academy with a worldview that has been 10,000 years in the making, and continues to grow and evolve.

– Michael Bopp, Lee Brown, Jonathan Robb, 2017, p. 6

Indigenous cultures, knowledge systems, and worldviews grew out of relationships with the land, from observation of cycles and patterns on the land, in the skies, and on the water to learning the behaviour of animals and recognizing how humans interact and build experiences. Observation and experimentation enabled a set of principles and practices that manifest as stories, laws, protocols, and approved practices, which provide a way to coexist in holistic and sustainable ways. As Gregory Cajete, a Tewa scholar, stated at a 2015 Banff Centre event, “The focus of native science … [is] finding ways to resonate with the natural world and the natural order.” These processes exist today in spite of contact and colonial legacies.

As a country, we have much to learn from Indigenous Peoples. However, the colonial mindset has viewed Indigenous Peoples as “the other,” as almost-humans with knowledge and physical resources to be extracted and used to build a new world. This mindset allowed settler researchers to research Indigenous Peoples without recognition of responsibility, conditions imposed on Indigenous Peoples by colonization. The marginalization of Canada’s Indigenous population was systematic and deliberate, resulting in catastrophic health conditions for people living on reserves across Canada (Daschuk, 2013). Poor health conditions, systemic assimilation, and general racism gave rise to new policies to remove Indigenous children from reserves for their education in residential schools. The poor health conditions on reserves coupled with poor educational experiences in the residential school system led to “new ‘unnatural’ pathologies, such as AIDS, diabetes, and suicide emerging under physical and social constraints experienced by Aboriginal communities today” (Daschuk, 2013, p. 186). Deficit-based research into these pathologies often involved unethical research practices on Indigenous peoples’ bodies, their cultures, and their knowledge. These research practices allowed such atrocities as:

While research on Indigenous Peoples has occurred since contact, recent geopolitical and societal shifts have influenced researchers and research disciplines to better consider how to work with and for Indigenous Peoples. Diligent, groundbreaking Indigenous scholars such as Linda Tuhiwai Smith, Sean Wilson, Margaret Kovach, and Kathy Absolon have shared perspectives, knowledge, and Indigenous research pathways. Furthermore, since the 1970s, Indigenous leaders have demanded rights and access to responsible and collaborative research. Research protocols and guidelines began to shift in the 1990s in Canada and across the globe. Many protocols developed to date are within the health field and were steered by Indigenous organizations such as the National Aboriginal Health Organization (ceased operations in 2012) and the First Nations Information Governance Centre. Other protocols developed relate to environmental sciences and biosecurity research – organizations such as the Inuit Knowledge Centre ensure research in Nunavut is co-developed, led, and supported by Inuit communities.

The Indigenous Research Protocols, Policies, and Declarations Timeline provides a snapshot of key pieces of policy and legislation that have shifted ethical research practice with Indigenous Peoples.

An interactive or media element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://opentextbc.ca/indigenizationresearchers/?p=465

Note: If you are not using the online version of this guide, you can find the timeline in Appendix A: Indigenous Research Protocols, Policies, and Declarations Timeline

Self-determination in a research agenda becomes something more than a political goal. It becomes a goal of social justice which is expressed through and across a wide range of psychological, social, cultural and economic terrains. It necessarily involves the processes of transformation, of decolonization, of healing and of mobilization as peoples. The processes, approaches and methodologies … are critical elements of a strategic [Indigenous] research agenda.

– Linda Tuhiwai Smith, 1999, p. 116

Interconnected, relational, and intersected are ways to describe an Indigenous research approach. These ways of knowing, being, and doing describe a non-linear approach to the research process as ontology, epistemology, axiology, and methodology and are “inseparable and blend from one into the next” (Wilson, 2008, p. 70).

In a Western research approach, action and participatory research come forward as critical research approaches that involve the participant, yet the researcher maintains control of the depth and type of interaction and manages data gathering and analysis.

In an Indigenous research approach, participants guide and embody the research process and results. Ownership, control, access, and protection of the data is held by the community, not the researcher. The researcher is part of the process of research in that they hold the ceremony or act of research. They intersect between the academy or funder and the community, and they ensure the relationships built in the research process continue past the project. This responsibility is ongoing, as many researchers who practice Indigenous research are part of the community or allies of the Indigenous community. As Indigenous voice gains prominence in research, these approaches are expanding the ways research can be held as a transformative change process. However, Indigenous voice and knowledge in research has required a few other processes to shift practice.

Since “The Green Report” was published in 1990 (British Columbia Ministry of Advanced Education Department, 1990), public post-secondary institutions in B.C. have tried to provide Indigenous space and voice and increase Indigenous learner success. The recommendations in the report have shaped current educational policy and created a foundation for dialogue and processes to emerge. These processes or approaches are Indigenization, decolonization, and reconciliation, and each holds various levels of importance in institutions due to relationships and partnerships with First Nations and Métis educational authorities and communities. These processes directly impact, inform, and guide how research can become a reciprocal and relational process. There has also been an increase in Indigenous graduates with bachelor’s, master’s, and doctoral degrees. Many of these graduates give back by either leading community-based research, becoming instructors in post-secondary institutions, or taking on educational leadership roles in institutions. Their ability to build a bridge between Indigenous communities and public post-secondary institutions makes them leading voices that support and guide Indigenization, decolonization, and reconciliation.

Indigenization involves the meaningful inclusion of Indigenous voice and perspective at various levels of the institution and provides space for Indigenous pedagogy to occur in the classroom. Indigenization is strengths based and acknowledges that both Indigenous and Western knowledge and perspectives are valid, authentic, and complementary. Indigenization works in a collaborative environment and acknowledges that there can be multiple approaches to support learner success. Institutions are exploring how to bring Indigenous epistemologies and pedagogies into practice to benefit all learners, not only Indigenous learners. Indigenization occurs in phases, best described by David Newhouse, an Onondaga scholar, at a 2015 SFU-UBC Graduate Student Symposium as follows:

The process of decolonization entails remembrance. … Remembering is an obligatory ingredient for the completion of the past in a manner that is respectful and honours the losses as we honour the strength of the ancestors and acknowledge their gifts to our present generation. Remembering means drawing on the strengths of my own past from which I can carve a future. It is the past that carries us into the future and contributes to the journey of the present. As human beings, we Siksikaitsitapi see ourselves as cosmic, because we are interconnected, related to all of the time and to all that there is.

– Betty Bastien, 2004, p. 47

Decolonization recognizes the power imbalances and the harm of normalizing Western knowledge in education as the only way of knowing and seeing all other knowledge systems and practices as lesser and invalid. Decolonizing practice is social-justice focused and strives to create places of truth-telling, revealing places of discomfort and challenging the status quo (Corntassel, 2011; Tuck & Yang, 2012). It does not mean we place ourselves into binary positions, but instead that we create spaces where similarities and differences can be explored and understood (Battiste, 2005). Decolonizing practice is not only for non-Indigenous researchers and educators to identify and challenge racist and unjust process and practice; it also requires vigilance from Indigenous communities to ensure Indigenous knowledge and practice are recognized, validated, and protected.

This process has gained prominence due to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada’s work to redress the legacy of residential schools. The 94 Calls to Action [PDF]. provide specific recommendations on ways to transform and change education and research; many post-secondary institutions are currently creating ways to address these calls to action. Reconciliation requires both Indigenous and non-Indigenous people to identify, recognize, acknowledge, and accept their respective responsibilities to change relationships, build common understanding, and make genuine, long-lasting change to Canadian society.

In this section, you have briefly examined the history of policies and processes that shape and support Indigenous voice and knowledge in post-secondary institutions. You have also reviewed the Research Protocols, Policies, and Declarations Timeline showing how Indigenous Peoples have created a voice in research at local, national, and international levels. The following activities are an opportunity for you to explore your research process and how it is affected and influenced by Indigenous perspectives and protocols.

Activities

Type: Individual

Time: 1 hour

Explore the Indigenous Research Protocols, Policies, and Declarations Timeline. (Note: If you are not using the online version of this guide, you can find the timeline in Appendix A.) As you are developing your research idea, what protocols and declarations influence and affect your research? Think of not only data gathering but also results dissemination.

Even if your research does not involve Indigenous knowledge or people, list two or three strategies from Indigenous protocols that can affect and influence your research design.

Type: Individual

Time: 45 minutes

Read the paper DNA on Loan: Issues to Consider when Carrying Out Genetic Research with Aboriginal Families and Communities [PDF] by Laura Arbour and Doris Cook about the Nuu-chah-nulth experience. Consider the following questions:

Type: Group

Time: 1–3 hours

In your institution or research location, conduct an internet scan of First Nations, Métis, and Inuit community resources included in the Indigenous Research Protocols, Policies, and Declarations Timeline. (Note: If you are not using the online version of this guide, you can find the timeline in Appendix A.) As a group, discuss the following:

Type: Group

Time: Ongoing

Host a reading group. Select one of the publications below to discuss positionality and researcher responsibility in an era of reconciliation:

Type: Individual or group

Time: 1–5 hours

Watch the 30-minute presentation Indigenous Knowledge and Western Science in which Cajete shares similarities and differences between Indigenous knowledge and Western science. Reflect and discuss in a circle dialogue:

The purpose of any ceremony is to build stronger relationships or bridge the distance between aspects of our cosmos and ourselves. The research that we do as Indigenous people is a ceremony that allows us a raised level of consciousness and insight into our world. Let us go forward together with open minds and good hearts as we further take part in this ceremony.

– Shawn Wilson, 2008, p. 11

For this section, you will explore how Indigenizing research is interconnected and relational. You will consider current knowledge-protection issues and recognize the steps to take when including Indigenous language in your research. You will also use an interconnected and intersected model and process called SPECIALTYPATHLIST.

Purpose of this section

This section provides a way to look and think critically about the scope of protocols and practice in research and how it can shape working relationships. Topics include:

This section can take up to 4 hours to complete on your own. Some group activities can occur over an academic semester.

When accessing Indigenous knowledge for research in the arts, cultural practices, scientific knowledge, kinship and social systems, ceremonial practices, and other forms of oral Indigenous knowledge, it is important to review and understand copyright and intellectual property laws (both domestic and international). This is to ensure the intellectual property and copyright of Indigenous knowledge keepers is protected and to identify any collective community rights, as defined by the Indigenous community. For instance, many research projects include a project logo – an image or illustration to represent the spirit and intent of the research. Some researchers use existing images, while others commission specific designs. If the researcher is using Indigenous artwork, then copyright and intellectual property rights have to be affirmed prior to publishing the research.

In the Western academic tradition, copyright is used to protect written resources produced by a person (or team). However, such copyright laws are problematic for Indigenous cultures. Within many Indigenous knowledge systems, oral permission is required before accessing cultural materials or practices such as legends, stories, songs, designs, crests, photographs, audiovisual materials, and dances. These practices and materials are owned and transferred by specific individuals, families, or groups within their respective Nations. Permission to use them is contextual to the researcher’s relationship with the owners, the intent of the research, and how the practices or materials will be shared. Permission may be specific to a single use; if you are adjusting your research for a different context, then permission will need to be secured again.

Protocols that exist around the use of Indigenous resources are specific to place, people, and time; hence, there is no generic code of conduct when working with Indigenous Peoples. Each First Nations, Métis, and Inuit community will have principles, practices, systems, and processes that flow from their community’s respective laws and traditions. This does not mean that Indigenous knowledge systems and art cannot be used, but researchers need to seek permission and properly cite and situate the knowledge used in their research before using Indigenous knowledge systems and expressions. Learning about these protocols from the community you are working with will contribute to the content and context of the research partnership agreement. Researchers need to build connections with Indigenous communities and knowledge keepers to seek oral permission. This may be challenging at times, and it may take time, but it is the responsibility of all researchers. If you or your institution has not obtained permission, it is important to investigate and secure permission from relevant individuals, families, authorities, agencies, and organizations.

Researchers should review and understand domestic and international laws and declarations to ensure the copyright and intellectual property rights of Indigenous artists and knowledge keepers are protected, as well as any collective community rights defined by the Indigenous community.

There is currently no single source of information about Indigenous Peoples and copyright and intellectual property. There are, however, several resources that provide practical guidance and tools for researchers about traditional and contemporary arts in all disciplines: visual, music and song, dance, theatre, storytelling, and new media. In a 20-minute JCUCairns TEDx talk from 2016, Terri Janke, an Indigenous lawyer and activist from Australia, discusses the potential of collaboration. True Tracks: Create a Culture of Innovation with Indigenous Knowledge documents a way to acknowledge and respect Indigenous cultural expression and knowledge through collaboration, consent, attribution, and protection.

In British Columbia and across all of North America, Indigenous languages continue to be endangered – some critically endangered, meaning they may be lost within the next generation. As a result, many communities view language revitalization as a top priority in various planning and research processes.

Researchers who want to incorporate an Indigenous language into their project need to ensure they are guided by the Indigenous community that speaks the language. As language conveys Indigenous culture, the more a researcher knows and understands the language of the community, the better the chances of creating a trusting relationship with community members. It is helpful to know that different communities that speak the same language will have dialect differences. There can also be different writing systems (orthographies) that are used by each language family or group. In some cases, a language family or group may use one or two different orthographies; for example, among Kwaḱwala and Liḱwala speakers (the same language family), two systems are used. Many (but not all) Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw communities use the U’mista orthography (an orthography created by the community) for Kwaḱwala learning resources; however, Liḱwala speakers use the International Phonetic Alphabet (an orthography created by Western linguists) when creating language learning resources. The First Peoples’ Cultural Council shares information about the diversity of Indigenous languages spoken across the province and highlights current language revitalization projects. The nuance of how a language is written and conveyed will be important in your research, especially if it is going to be shared with language keepers and teachers.

It is important to ensure a traditional language is used only with the direct involvement, permission, and guidance of the community. As referenced in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s final report, Indigenous languages belong to the communities and should be used only if those communities approve of their use. This addresses protocol around the use of an Indigenous language. It is also important to have a community’s involvement, because translation of research ideas from English to an Indigenous language is not always a straightforward matter of translating words and phrases, but rather a process of ensuring ideas and worldviews are reflected in the choice of words.

In terms of individual commitment, researchers should also consider seeking direction from a fluent speaker to learn an appropriate greeting and farewell. This will demonstrate their commitment to learning and respecting protocols and help to build a trusting relationship.

Using Indigenous cultural objects as metaphors (for example, a basket weaving or a totem pole) may seem like an effective way to visually relate a research idea, but it is important to first consult with the First Nations, Métis, or Inuit communities that hold the intellectual property rights – that is, the traditions from which you are creating a metaphor from – and seek guidance and permission to do so. Not seeking permission and guidance on the appropriate use of an Indigenous cultural object or practice is cultural appropriation. Misappropriation is a one-sided process in which one entity benefits from using another group’s intellectual and cultural property without that group’s permission or giving something in return.

To avoid misappropriation, it is important to connect with the First Nations, Métis, or Inuit community from which the metaphor originates, as the cultural reference may be considered sacred to that community, or it may be owned by specific families and not appropriate for use as a research metaphor. It is also important to ensure the metaphor is used correctly. Inaccurate information about many Indigenous metaphors has developed over time among non-Indigenous people. For example, the totem pole has frequently been used as a metaphor for order, with the bottom referencing a less important concept, but this is wrong. Many First Nations communities that have created totem poles for countless generations consider the bottom figure as important as all other figures, because it is regarded as the figure that holds all of the others up.

The Medicine Wheel is another metaphor that is often used inaccurately. There is a tendency to assume that there is only one model for the Medicine Wheel, when in fact there are many models. Medicine Wheels may have different colours, which may be seen in a different sequence around the circle, and different animals may also be represented on different Medicine Wheels. Relevance and place are important to consider when using this research metaphor. If you use a Medicine Wheel that represents Dakota beliefs in a Cree community research project, you are not respecting the Cree community, as the colours and meaning of each realm are different. To ensure you are using a metaphor that represents the beliefs of the Indigenous community you are working with, approach people who belong to the community and ask them to direct you to the community’s cultural stewards, who can guide you on the appropriate use of images and meanings.

Incorrectly using a metaphor has the potential of negatively impacting the research project and the relationship with community. Think Before You Appropriate: Things to Know and Questions to Ask in Order to Avoid Misappropriating Indigenous Cultures [PDF] is a guide created through Simon Fraser University’s multi-year Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC) project, Intellectual Property Issues in Cultural Heritage Project, that explores responsible and ethical collaborations.

Post-secondary Indigenous educators Dianne Biin (Tsilhqot’in) and Lou-ann Neel (Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw) designed the community planning tool SPECIALTYPATHLIST during their years as Indigenous community developers and researchers to help with developing programs, projects, policies, and events. This checklist focuses on interconnections and builds project and approach relevancy by helping researchers consider all aspects that may be affected by a project.

SPECIALTYPATHLIST was developed over decades of working in and with First Nations communities, agencies, and organizations across British Columbia. It supports Indigenous community development, arts revitalization, and residential school healing through cultural practice. This planning tool is more in-depth and relational than a business STEEP analysis (social, technological, economical, environmental, and political) or an appreciative inquiry SOAR approach (strengths, opportunities, aspirations, and results). This tool enables Indigenous voice to be involved in the research design, data gathering, and dissemination of results.

In 2000, Neel and Biin used SPECIALTYPATHLIST for a multi-funder action research and training project that lasted over two years. Knowledgeable in the Ways of Song began as an idea to digitize archival collections of songs from the Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw peoples. The project became more complex when many community members said they were having difficulties accessing archival recordings to revitalize.

What started out as a simple idea to digitize songs became a multi-layered process involving training community members how to recover, restore, and re-record songs from one family’s collection. SPECIALTYPATHLIST helped researchers determine the depth of this project during the planning stage. The researchers explored how digitizing can be a model for Indigenous family recovery, revitalization, and skills development. They worked with youth, master singers who were fluent language speakers, Elders, archivists, recording studios, and MIDI music technicians to restore two songs back to a family.

Once the model was tested, community members who had been trained were able to support their families in restoring songs. The reciprocity, generosity, respect, and relevance of the project was realized only by using SPECIALTYPATHLIST.

SPECIALTYPATHLIST is an acronym for the following aspects a researcher should consider when undertaking a research project within an Indigenous community:

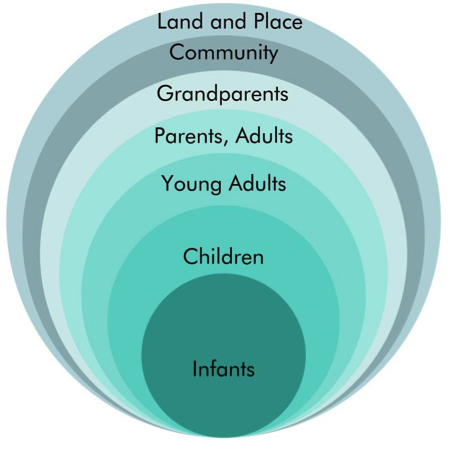

The following diagrams demonstrate how to use this planning tool to initiate dialogue with various members of a community and acknowledge how land and place affect the design and delivery of a project. In Figure 2.2, consultations and conversations are not hierarchical but instead organic in the process of determining the depth and relevance of a project. Figure 2.3 shows the benefits and impacts of a project beyond the initial scope of the project. While these categories change in importance, they provide a basis for ways to solidify your research idea and intention.

Note: If you are not using the online version of this guide, you can find the annotated diagrams information (Figure 2.2, Figure 2.3) in Appendix B.

An interactive or media element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://opentextbc.ca/indigenizationresearchers/?p=484

Figure 2.2: Consultations and conversations using SPECIALTYPATHLIST within a community to determine project parameters and influences. This diagram can be viewed in Appendix B.

An interactive or media element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://opentextbc.ca/indigenizationresearchers/?p=484

Figure 2.3: Using SPECIALTYPATHLIST as a Dialogue Tool with Community Authorities. This diagram can be viewed in Appendix B.

SPECIALTYPATHLIST has many benefits, including:

In this section, you gained some depth in how an Indigenized research project can be planned. You have also been made aware of the importance of how metaphor and imagery can help a research project gather, analyze, and disseminate results in a respectful way. The following activities examine how you can make your research interconnected, respectful, relational, responsible, and reciprocal.

Activities

Type: Individual

Time: 1 hour

Review the Canadian Copyright Act, the Status of the Artist Act, and the website of the Canadian Artists’ Representation/Le Front des artistes canadiens to learn more about the rights of artists and best practices and standards around the use of artworks.

Review the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) and the Calls to Action of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). Interpret how UNDRIP and the TRC Calls to Action relate to community negotiation and protocols in relation to your research project from beginning to end.

Visit the Intellectual Property Issues in Cultural Heritage, Canada Council for the Arts Research Library, and the World Intellectual Property Organization websites. Check the resources, reports, and proceedings sections, and identify at least three resources that inform your research project.

Type: Individual or group

Time: 1–4 hours

Visit the First Peoples’ Cultural Council website and identify various community agencies and resources for language revitalization and learning to look for resources that relate to your research project.

Connect with a First Nations, Métis, or Inuit community to explore how various words and phrases might be translated. Note any differences between the literal meanings of English words and phrases and those from the Indigenous language. Consider how this might change the research goals, objectives, and activities.

Type: Individual

Time: Ongoing

Read Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor (Tuck & Yang, 2012) and reflect on what needs to be “unsettled” in your research design and process for gathering and sharing data. Are there areas of your research design that are collaborative and respectful?

Type: Individual

Time: Ongoing

Using SPECIALTYPATHLIST, explore who needs to be involved in the research partnership agreement. For example, use the list to ask if there are any social, political, economic, cultural, or other benefits or implications of this research.

Type: Group

Time: 1–5 hours

Locate research and other examples of where an Indigenous tradition was used as a metaphor. Locate resources created by the Indigenous community from which the tradition is derived and contrast its use as a metaphor.

Type: Group

Time: Ongoing

Type: Group

Time: Ongoing

If you have developed a research inquiry, present it to various audiences (e.g., instructors, students, advisors), and gauge response and understanding of intent.

Type: Group

Time: 1–3 hours

Watch this half-hour video from Julie Bull, Inuk researcher, The Intersection of People, Policies and Priorities in Indigenous Research Ethics. Discuss the following questions about research approach:

In this section, you will consider Indigenous approaches to research from an ethical perspective. Developing a strong ethical stance requires conversations and agreements prior to starting research. Research ethics boards or committees in post-secondary institutions may require a research agreement that upholds Indigenous ownership, control, access, and protection of research involving Indigenous Peoples and communities. These boards and committees may also have such considerations only when the research funder requires them to do so. Most institutional practice falls somewhere in between. First Nations and Métis communities and sometimes urban organizations may also have separate agreements or protocols. At times, you will need to walk and negotiate between different requirements and assumptions. In this section, you will navigate ethical considerations of Indigenous research and be introduced to a community relationship toolkit that holds responsible, respectful, and protective measures.

Purpose of this section

This section provides you with some insights into successful community relationship building. Topics include:

This section could take you 2–4 hours depending on the depth of collaboration and permissions to gain in your research. Group activities can take up to 3 hours to complete.

In November of 2016, I had the pleasure of visiting Haida Gwaii. I was travelling to visit students enrolled in a Bridging to Trades program in Skidegate. On my way home I was waiting in the Massett Airport to fly back to Vancouver. While there I started a conversation with some young students from a university in the Lower Mainland who happened to be doing some research in Haida Gwaii. Since I had attended a community event the previous evening, I asked the students if they had had the opportunity to attend some activities in the communities and meet some of the locals. The students mentioned that although they were on the island for a number of weeks, they did not ever have that opportunity. I was struck by this as I feel that the most important aspect the students would have come away with was a relationship with the Indigenous people of the islands. I do realize that we have very strict research protocols, however, by not fostering relationships, we are not creating spaces for reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples in this country. Any type of research is applicable to reconciliation if we want it to be!

– John Chenoweth, personal communication, 2017

Ethics are considered to be a set of practices and social behaviours based on values. Indigenous research ethics respect leadership and require developing trusting relationships. While there is much diversity among Indigenous Peoples and Nations overall, Indigenous ethics resonate with the values of honour, trust, honesty, and humility; they reflect commitment to the collective and embody a respectful relationship with the land. It is the responsibility of the researcher to identify how Indigenous ethics can influence research design and process.

In Indigenous communities, the process of ethical thinking begins at birth with storytelling as the primary learning process. Storytelling is used to guide behaviour and solidify belonging and responsibility to the family, community, and larger world. Through stories, a child develops identity and learns about moral responsibility. Through stories, the community articulates and embraces its shared valued system or mindset. Ethical thinking emerges from a community’s customs, teachings, and ideals. Researchers must take this mindset into account when conducting research in Indigenous communities and with Indigenous participants.

In The Seven Sacred Teachings of White Buffalo Calf Woman, Bouchard and Martin (2009) explain how Indigenous teachings involve notions of taking care of one another, collective decision-making, and sustainability. All are based on a value system that locates itself within the Anishinaabe seven grandfather sacred teachings. The sacred teachings of respect, bravery, honesty, humility, truth, wisdom, and love are significant guidelines that resonate in most Indigenous cultures. The teachings are represented by seven sacred animals each having a special gift to help the people understand and to maintain a connection to the land and to each other. The values embodied in the teachings coupled with storytelling, and articulated through Indigenous language, reinforce Indigenous ways of being and doing. In other words, fortifying ethical thinking lends itself to ethical practice.

Researchers need to understand and recognize the significance of Indigenous shared values and the community conventions that accompany them. Understanding Indigenous thought requires taking time to learn the ways of the Indigenous community you are working with and locating it within the core principles of the Tri-City Council Policy Statement, version 2 (TCPS 2), which include respect for persons, concern for welfare, and justice. Learn by connecting with community Elders, knowledge keepers, and leaders as a natural prelude to conducting a research study. Ensure your research study will benefit community life. Know how the roles and responsibilities of the Elders and leaders (both hereditary and elected) shape protocols, and recognize the kinship and other governance systems will influence who is involved and when research can occur.

Furthermore, it is critical to know that Indigenous Peoples’ experience with Canada carries a legacy of oppression and colonization. The devastating impacts of residential schools, the child welfare systems, and other colonial experiences have created deep losses for Indigenous Peoples. Indigenous participants in your research may be vulnerable to experiences of secondary or retriggered trauma. You must be very careful when planning and doing research that involves personal or intergenerational loss. If you are doing research about child welfare or residential schools, you will need to consider that Indigenous people tend to experience the loss of a child or children from a family and community as a loss to the Nation. This is demonstrated by Dr. Deborah Canada who provided a Métis mindset in her research, The Strength of the Sash: The Métis Peoples’ Model of Child Welfare [PDF].

While there are commonalities between Indigenous research and Western research philosophy, there are some fundamental differences. The Western academy’s notion of freedom often links to freedom in inquiry, opinion, and the disbursement of information. Indigenous concepts of freedom focus on how the people convey stories, or collect data, as a lending of knowledge to the researcher, and they have the freedom to determine how it is placed in the research. Clearly, although both entities share a notion of freedom, the action applied is different.

Researchers need to apply particular considerations when conducting research with Métis people. The researcher must be able to clarify that Métis research is different from other Indigenous research because of the unique experiences of Métis peoples. It is critically important to understand the diversity among Métis peoples. To mitigate ethical dilemmas in conducting Métis research, review the Principles of Ethical Métis Research [PDF]. Suffice to say, Métis research, like other Indigenous research, makes a difference in the lives of Indigenous Peoples and therefore should be approached mindfully and carefully.

Researchers must also take into account the ethical rules of each community as well as the concept of non- invasiveness. Respecting the role of leadership is a must and a way to move the research to another level. One of the most significant roles of leadership is to ensure that the community remains the owner of Indigenous knowledge and the community maintains the right of control and access. Without the support of leadership, research can be seen as a mis-inquiry into Indigenous knowledge and ways of life.

The ethics of Indigenous research are complex and require much preparation, but research plays an extremely important role in social transformation and reconciliation. Do this work well and you may be gifting a collaborative future.

Protocols for First Nations, Métis, and Inuit communities are unique to each community. While there may be some similarities in practices, it is important to learn about the protocols of the community you will be working with on your research project.

While many communities have participated in research projects previously, and some communities have developed their own research protocols, others may not have engaged with post-secondary institutions or other organizations on research projects and may not have formal written protocols directly related to research. Researchers need to talk with community leaders about the community’s experience with research and what guidelines are in place. You will need to ensure you can adhere to existing community protocols and practices or work closely with community representatives to develop protocols as part of reaching a formal, written agreement prior to commencing research activities.

Indigenous communities have been researched over and over again, and more often than not this has occurred without consultation or permission. Some Indigenous communities may be distrustful of researchers, and you may have to learn about their past experiences. Sit quietly and listen; do not defend or explain. Make it clear you are there to hear the community’s voice, and then make respectful inquiries about how – if you get their permission

Asking for permission is a vital component of the process, and you may be required to ask for permission at various levels. Seek support and advice as you move along the permissions processes. As you move through the permissions process, recognize the following:

As you work through this guide, you will begin to realize that there needs to be a conversation and agreement on what you can use in your research to strengthen both the data gathering and analysis. In British Columbia, post- secondary institutions are engaged in and supportive of educational partnerships with Indigenous institutes and educational organizations. A toolkit developed in 2011 provides a way for institutions to engage and accommodate learning partnerships.

The Post-Secondary Education Partnership Agreement Toolkit [PDF] was jointly developed by the Indigenous Adult and Higher Learning Association, the University of Victoria, and the Nicola Valley Institute of Technology. Part 1 provides situational information and history. Part 2 and Appendix 3 have information and procedures that can aid researchers in building a responsible, ethical, reciprocal, and relevant agreement.

In this section, you explored how ethics reflects beliefs and values. How we value and express ethics depends on our own teachings, so we need to create a place of trust and understanding to hold conversations on what research can be. The Post-Secondary Education Partnership Agreement Toolkit is a good way to build your own approach to research agreements. The following activities build on the information shared in this section.

Activities

Type: Individual

Time: 1 hour

Type: Individual

Time: Ongoing

Like First Nations Peoples, Métis Peoples have their own language, rituals, customs, culture, and governance systems. Researchers need to carefully consider this when conducting research with Métis Peoples. Explore the following resource, and see if you can describe the difference between Métis and First Nations culture in your area or region: Canada’s First Peoples: The Métis

Type: Individual

Time: Ongoing

Type: Individual

Time: Ongoing

Type: Individual or group

Time: 1–5 hours

Begin this activity alone, and then gather in a group with four or five other people to share and discuss the following:

In this section, you will explore examples of collaborative and reciprocal research with Indigenous communities. Conducting research that is respectful, relevant, responsible, and reciprocal can be a difficult undertaking (Archibald, 2008; Pidgeon, 2008). Building trust takes time as many Indigenous people mistrust researchers due to the negative legacy of research on the topic of Indigenous Peoples. This section outlines projects as examples to express how Indigenous communities can benefit from reciprocal and interconnected research relationships. The projects, which the authors have contributed to and supported, range from exploring the concept and roles of reconciliation to supporting linguistic visions of Indigenous communities.

Purpose of this section

For this section, you will take what you have learned in the previous sections and see how approaches, agreements, and relationships have Indigenized, decolonized, and reconciled practice. Topics include:

This section will take 2 hours to complete on your own; some groups activities can be done in the classroom or in Indigenous communities with educational partners.

In 2001, the SENĆOŦEN- and Hul′q′umi′num′-speaking people began planning with the linguistics department at the University of Victoria for ways their communities could deliver more language learning opportunities for all age groups.

Because the linguistics department was working closely with these communities on other important language revitalization projects, planning for new approaches continued to involve fluent speakers, language teachers, and language curriculum developers from communities across southern Vancouver Island: (W′SANEĆ (Saanich), Sc’ianew (Beecher Bay), T′Sou-ke (Sooke), Khowutz′un (Duncan), and Stz′uminus (Chemainus).

The project was guided by a steering committee with language speakers from each of the participating communities. The steering committee provided direction and guidance on each of the community-based initiatives undertaken as part of the larger research project.

In addition, the project was developed to ensure several community-based coordinators could be hired to work closely with each community to carry out each initiative. This was important, as it empowered and enabled each community to be responsive to any unanticipated changes and to seek any further guidance it might need from the steering committee and lead investigators.

This project is an excellent example of how tools such as SPECIALTYPATHLIST can be used to work through planning processes between researchers and communities and to enable strategies and actions to be developed in an informed way.

Goals of this research project were to:

Learn more about the Salish CURA project.

In 2016, Selkirk College received a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) grant to conduct research on exploring reconciliation through community college education. Through this research project, Selkirk College addressed the challenge of identifying its role as a public post-secondary institution in the work of reconciliation. Specifically, as a community college located in a rural region with diverse Indigenous communities, Selkirk College asked the question: How does a community college respectfully engage in reconciliation through education with the First Nations and Métis communities in the traditional territories in which it operates?

This research was framed in an Indigenous paradigm where the investigators worked collaboratively with their community members, including First Nations, Métis, and other Indigenous community members (non-status/organizations), and it was participatory, with the cooperation of Elders, residential school survivors, and student and youth groups. These groups decided, along with the lead investigator, how they would prefer the data to be collected. Some of the options for the participatory approach to data collection included focus groups, gatherings, and interviews.

By having a deeper understanding of its role in reconciliation, the college can strive to create a post-secondary education environment that includes authentic Indigenous voice, is based on truth and mutual respect, and follows the values and behaviours that the community identifies. In exploring the meaning of reconciliation, the college recognizes that each First Nations, Métis, and other Indigenous community throughout its operational region requires an independent dialogue to determine the behaviours and values that the community wishes to see reflected in the college’s efforts in reconciliation.

This project was unique in organization and consisted of two research teams, which were led by two Indigenous primary investigators designated by the First Nations. Informed by these values and behaviours, the research team developed tools to implement “systemic change” in education and address the knowledge and values gap for college staff, instructors, and students wanting to understand their role in the reconciliation efforts. These efforts will continue to strengthen the relationships between the First Nations, Métis, and other Indigenous communities and the cluster of post-secondary institutions throughout the B.C. Southern Interior.

Goals of this proposed research project were to:

The research partnership between the Northern Institute of Charles Darwin University, Plant & Food Research of New Zealand, and the Plant Biosecurity Cooperative Research Centre (PBCRC) with Māori and Northern Territory knowledge authorities built an engagement model for how Indigenous communities can support and lead research and environmental management on their traditional territories.

Weeds and noxious plant species and animals introduced to the Australian and New Zealand lands have significantly impacted Indigenous communities’ economic, social, and food land resources. While regulatory authorities and relevant agencies have worked with Indigenous communities, they needed to create an effective and respectful community engagement process that held Indigenous voice and knowledge.

The Aboriginal Indigenous Engagement Model was conceptualized from previous plant biosecurity operations of Mimosa pigra on Aboriginal land in Australia’s Northern Territory, which had buy-in from multiple agencies to eradicate biosecurity incursions. The work by the PBCRC’s Indigenous engagement team in building engagement models for two continents had not been attempted before. As Australian and Māori knowledge keepers converged to discuss cultural knowledge, similarities in the protocols of food preparation came forward.

The Aboriginal Indigenous Engagement Model was designed to draw parallels between the immutable stages and principles of mirrwanna seed processing and the essential steps and principles of effective community engagement. The model included the rationale for each step and the underpinning values in Aboriginal culture. For the Warramirri, Mak Mak Marranunggu, and other Yolŋu language groups, key values include:

The Aboriginal Indigenous Engagement Model builds cross-cultural links and provides a way for communities to respond to biosecurity incursions that threaten traditional cropping practices and force the adoption of alternative cropping, surveillance, and management technologies.

These engagement models have broad application and can target government agencies and officials; research, science, and technology providers; regulatory and industry agencies involved in biosecurity incursions; and community stakeholders. The key is to develop consistency in the process used by these agencies when engaging Indigenous communities and community stakeholders. The research project is now figuring out ways to incorporate these engagement models as protocols and procedures for inclusive and relevant involvement in research and policy.

The careful collection of traditional knowledge from Elders in both Māori and Aboriginal communities created trust, understanding, and a willingness to share details that the research teams could embed in the models. It was also acknowledged that there are situations in which, for cultural reasons, information could not be shared and alternative paths were necessary. This methodology has resulted in models for engagement developed by Indigenous communities for Indigenous communities, thereby increasing the probability of adoption and success.

For more information, see the following websites:

Although these Indigenous-led and Indigenized research examples are not definitive, they provide a snapshot of the innovative, inclusive, and reciprocal work that can occur in research. The following activities are an opportunity for you to once again visit your research idea and explore how to create spaces for self-determination.

Activities

Type: Individual

Time: 1–2 hours

Type: Group

Time: 1 hour

Thank you for joining us on this exploration. As with other Indigenous research guides, this guide focuses on why Indigenous voices and perspectives are needed in research inquiry and practice. We encourage you to engage with Indigenous knowledge keepers and authorities to continue this dialogue

Indigenizing research involves informing yourself about how research has been used to cause harm to Indigenous Peoples and communities. Spending time with this information helps guide you in recognizing the processes that need to be decolonized, such as engagement, inclusion, ownership, and protection of Indigenous knowledge. Indigenizing your process with new research paradigms creates a space for you to consider how to connect your research to Indigenous values. The ceremony of research is announcing your intention, inviting the right people to come together, telling stories, providing a space for work to occur, nourishing our spirit, and recognizing that we walk together in what results from the ceremony of research.

As we opened this guide with an invitation to engage, we close with another Kwak̓wala phrase, la’ams ǥwała’, We are all done now, or You are all finished.

There is a rich and growing body of books, videos, and articles focusing on Indigenizing education. The following resources have been chosen to support the journey outlined in this guide.

Arts Law Centre of Australia. (2012, June 12). Indigenous knowledge consultation: Have your say (letter to IP Australia). Woolloomooloo, NSW: Arts Law Centre of Australia. (letter to IP Australia) [PDF]" data-url="https://www.artslaw.com.au/images/uploads/Submission%20to%20IP%20Australia%2014-6-12(1).pdf">https://www.artslaw.com.au/images/uploads/Submission%20to%20IP%20Australia%2014-6-12(1).pdf

Crosby, M. V. (1994). Indian art/Aboriginal title (Unpublished master’s thesis). University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC. https://open.library.ubc.ca/cIRcle/collections/ubctheses/831/items/1.0087525

First Peoples’ Cultural Council. (2014). Report on the status of B.C. First Nations languages 2014 (2nd ed.) Brentwood Bay, BC: First Peoples’ Cultural Council. http://www.fpcc.ca/files/PDF/Language/FPCC-LanguageReport-141016-WEB.pdf

Hansen, S. A., & VanFleet, J. W. (2003). Traditional knowledge and intellectual property: A handbook on issues and options for traditional knowledge holders in protecting their intellectual property and maintaining biological diversity. Washington, DC: American Association for the Advancement of Science. https://community-wealth.org/sites/clone.community-wealth.org/files/downloads/book-hansen-vanFleet.pdf

Law Library of Congress. (2010). New Zealand: Māori culture and intellectual property law. https://www.loc.gov/law/help/nz-maori-culture/nz-maori-culture-and-intellectual-property-law.pdf

National Congress of American Indians Policy Research Centre. (n.d.). Research that benefits Native people: A guide for tribal leaders. https://www.ncai.org/policy-research-center/research-data/NCAIModule1.pdf

World Intellectual Property Organization. (n.d.). Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works. Geneva, Switzerland: World Intellectual Property Organization. http://www.wipo.int/treaties/en/ip/berne/

First Peoples’ Cultural Council. First voices language portal. https://www.firstvoices.com/

Center for Digital Scholarship and Curation, Washington State University. Mukurtu CMS. Indigenous traditional knowledge digital heritage system. Mukurtu is a Warumungu word meaning “dilly bag,” or a safe keeping place for sacred materials. https://mukurtu.org/

University of British Columbia. Indigenous Portal. Highlights faculty-led, student-led, and community-led research projects. http://aboriginal.ubc.ca/research/

University of Northern British Columbia. National Collaborating Centre for Indigenous Health. One of six national public health centres, publicly funded since 2005. https://www2.unbc.ca/nccih

University of Victoria. Centre for Indigenous Research and Community-Led Engagement (CIRCLE). https://www.uvic.ca/research/centres/circle/

Archibald, J. (2008). Indigenous storywork: Educating the heart, mind, body and spirit. Vancouver, BC: UBC Press.

Bastien, B. (2004). Blackfoot ways of knowing: The worldview of the Siksikaitsitapi. Calgary, AB: University of Calgary Press.

Battiste, M. (2005). Indigenous knowledge: Foundations for First Nations. World Indigenous Nations Higher Education Consortium Journal, 2005(1), Article 19251. https://journals.uvic.ca/index.php/winhec/article/view/19251

Benson, E. (2013, October 28). Appropriation (?) of the month: Four rooms and a stone bowl [Blog post]. https://www.sfu.ca/ipinch/outputs/blog/appropriation-month-four-rooms-and-stone-bowl/

Bopp, M., Brown, L., & Robb, J. (2017). Reconciliation within the academy: Why is Indigenization so difficult? Four Worlds Centre for Development Learning. http://www.fourworlds.ca/pdf_downloads/Reconciliation_within_the_Academy_Final.pdf

British Columbia Ministry of Advanced Education Department. (1990). Report of the Provincial Advisory Committee on Post-Secondary Education for Native Learners (The Green Report).

Cajete, G. (2000). Native science: Natural laws of interdependence. Sante Fe, NM: Clear Light Publishers.

Colleges and Institutes Canada. (2015). Indigenous education protocol for colleges and institutes. https://www.collegesinstitutes.ca/policyfocus/indigenous-learners/protocol/

Corntassel, J. (2011, January 12). Indigenizing the academy: Insurgent education and the roles of Indigenous intellectuals [Blog post]. https://www.ideas-idees.ca/blog/indigenizing-academy-insurgent-education-and-roles-indigenous-intellectuals

Daschuk, J. W. (2013). Clearing the plains: Disease, politics of starvation, and the loss of Aboriginal life. Regina, SK: University of Regina Press.

Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami & Nunavut Research Institute (2007). Negotiating research relationships with Inuit communities: A guide for researchers. S. Nickels, J. Shirley, & G. Laidler (Eds.). Ottawa, ON, and Iqaluit, NU: Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami and Nunavut Research Institute.

Mosby, I. (2013). Administering colonial science: Nutrition research and human biomedical experimentation in Aboriginal communities and residential schools, 1942-52. Social History, 36(91), 145–172.

Pidgeon, M. (2008). Pushing against the margins: Indigenous theorizing of “success” and retention in higher education. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, 10(3), 339–360. doi:10.2190/CS.10.3.e

Smith, L. T. (1999). Decolonizing methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. New York, NY: Zed Books Ltd.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2015). What we have learned: Principles of truth and reconciliation. http://www.trc.ca/assets/pdf/Principles%20of%20Truth%20and%20Reconciliation.pdf

Tuck, E., & Yang, K. W. (2012). Decolonization is not a metaphor. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, 1(1), 1–40. https://jps.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/des/article/view/18630

Universities Canada. (2015, June 29). Universities Canada principles on Indigenous education. https://www.univcan.ca/media-room/media-releases/universities-canada-principles-on-indigenous-education/

Wichar, D. (2004, December 16). Nuu Chah Nulth blood returns to west coast. Ha-Shilth-Sa, 31(25), 1–3. https://issuu.com/hashilthsa/docs/25_december_16__2004

Wilson, S. (2008). Research is ceremony: Indigenous research methods. Black Point, NS: Fernwood Publishers.

A trade language spoken across the Pacific Northwest that mixes Chinookan, Nuu-chah-nulth, English, French, and other European languages. It’s also known as Chinuk Wawa.

A recognition of the power imbalances and the harm of normalizing Western knowledge in education as the only way of knowing and all other knowledge systems and practices as lesser and invalid. Deconstructing colonial ideologies involves valuing and revitalizing Indigenous knowledges and approaches and questioning biases and assumptions.

A Kwaḱwala phrase that translates in several ways, depending on the context it is spoken in. It can mean a welcome or a greeting, a form of engagement, or to give thanks, because it translates to “Come, breathe of the same air.” See First Voices: Kwaḱwala Phrases.

A Kwaḱwala term meaning one who is allowed or has permission. The term reflects a researcher’s responsibility and ongoing role in Indigenous research. While it takes a person a lifetime to develop into this role, it is not done alone; there are helpers, guides, and teachers along the way. See First Voices: Kwaḱwala Phrases.

A relational and collaborative process that involves various levels of transformation, from inclusion and integration to infusion of Indigenous perspectives and approaches in education.

Worldviews based on a set of principles and practices that stretch back to when Indigenous Peoples were placed on the land. These manifest as stories, laws, protocols, practices, and agreements and provide a way to coexist in a holistic and sustainable way. These processes exist today, in spite of contact and colonial legacies.

A language spoken by Métis people, mixing words from French, Cree, and Dene.

Ways of interacting with Indigenous people in a manner that respects traditional ways of being. Protocols are unique to each Indigenous culture and are a representation of a deeply held ethical system and traditional ways of doing and relating.

A process that requires both Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples to identify, recognize, acknowledge, and accept their respective responsibilities to change relationships; build common understanding; and make genuine, long-lasting change to Canadian society.

Significant ways of being that are represented by sacred animals that hold special gifts to help people understand and maintain a connection to the land and to each other. The values embodied in the teachings and the stories reinforce an Indigenous mindset.

Indian Control of Indian Education policy paper

States that research must benefit and support First Nations communities’ decisions and planning. Academic researchers are responsible to First Nations communities, and communities must have control of information.

Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples implements Ethical Guidelines for Research

Signifies a change in relationship by implementing research protocols to work with the consent of “Aboriginal Peoples” rather than conduct research about Aboriginal Peoples. Over 350 research projects were conducted between 1991 and 1994 to support the commission’s report.

Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples Report released (five volumes)

Recommends the development of research relationships with Aboriginal Peoples to support self-determination.

Ownership, control, access, and possession (OCAP) standards established

First instance of research standards created by First Nations health professionals for health researchers for ownership, control, access, and possession of data.

Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans (TCPS)