Moon of the Crusted Snow: Reading Guide

Moon of the Crusted Snow: Reading Guide by Anna Rodrigues and Kaitlyn Watson is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

OE Lab at Ontario Tech University

Moon of the Crusted Snow: Reading Guide by Anna Rodrigues and Kaitlyn Watson is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

1

Ontario Tech University acknowledges the lands and people of the Mississaugas of Scugog Island First Nation. We are thankful to be welcomed on these lands in friendship. The lands we are situated on are covered under the Williams Treaties and the traditional territory of the Mississaugas, a branch of the greater Anishinaabeg Nation, including Algonquin, Ojibway, Odawa and Pottawatomi. These lands remain home to a number of Indigenous nations and people.

2

This book is best viewed via the online, Pressbooks format. However, a pdf format is also made available. There are hyperlinks throughout the resource linking to additional resources, videos embedded in the sections, as well as passages copied from the book. This is not an electronic version of Moon of the Crusted Snow.

There are seven themes developed from the book’s content, however, they are not exhaustive. Each theme will include some or all of the following:

You may choose to use this resource as a thematic guide based on the subject or course you are teaching. You may also use this to accompany a chapter-by-chapter analysis of Moon of the Crusted Snow and use the resources, discussion questions, and activities as they arise out of the novel.

3

Thank you to the students employed by the OE Lab for working hard to make this book a reality. Congratulations on your achievement!

Editors: Abida Choudhury, Hasan Ahmad, Noopa Kuriakose, Pranjal Saloni, Shreya Patel

Project Managers: Rebecca Maynard, Sarah Stokes

Suggested Attribution for This Work: Rodrigues, Anna & Watson, Kaitlyn. Moon of the Crusted Snow: Reading Guide. OE Lab at Ontario Tech University, 2021, licensed under a CC BY NC SA 4.0 International License, unless otherwise noted.

Ontario Tech University is proud to host the OE Lab – a student-run, staff-managed group that brings content and technological expertise to the timely creation of high quality OER that will be used directly in an Ontario Tech course by Ontario Tech students.

If you adopt this book, you will be using a work created by students as an experiential learning and employment opportunity. Please let us know if you are using this work by emailing oer@ontariotechu.ca.

4

Moon of the Crusted Snow by Waubgeshig Rice is a fictional novel that looks at how an Anishinaabe First Nation, in northern Ontario, deals with an unknown event that leaves the community isolated, without power or phone service, and limited food sources as winter sets in.

In 2018, Dr. Anna Rodrigues approached author Waubgeshig Rice with the idea of collaborating on an open educational guide for his novel, Moon of the Crusted Snow, when she discovered that OERs for books written by Indigenous authors were lacking. That collaboration resulted in an online educational guide launching in 2019 that was well received by educators across Canada. In early 2021, Waubgeshig and Anna decided to update the guide and, at that time, Dr. Kaitlyn Watson, from the Teaching and Learning Centre at Ontario Tech University, joined the project. As part of this update, themes from the original resource have been expanded and a new theme which explores connections between the novel and the global pandemic have been added.

In December 2018, Waubgeshig Rice sat down with ![]() Shelagh Rogers from The Next Chapter to discuss his recently published book, Moon on the Crusted Snow.

Shelagh Rogers from The Next Chapter to discuss his recently published book, Moon on the Crusted Snow. ![]() The Next Chapter is a Canadian Broadcast Corporation radio program focused on Canadian writers and songwriters.

The Next Chapter is a Canadian Broadcast Corporation radio program focused on Canadian writers and songwriters.

Waubgeshig Rice is an author and journalist from Wasauksing First Nation on Georgian Bay. His first short story collection, Midnight Sweatlodge, was inspired by his experiences growing up in an Anishinaabe community and won an Independent Publishers Book Award in 2012. His debut novel, Legacy, followed in 2014, with a French translation published in 2017. His latest novel,

Moon of the Crusted Snow, became a national bestseller and received widespread critical acclaim, including the Evergreen Award in 2019. His short stories and essays have been published in numerous anthologies.

His journalism experience began in 1996 as an exchange student in northern Germany, writing articles about being an Indigenous youth in a foreign country for newspapers back in Canada. He graduated from Ryerson University’s journalism program in 2002. He spent most of his journalism career with the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation as a video journalist, web writer, producer and radio host. In 2014, he received the Anishinabek Nation’s Debwewin Citation for excellence in First Nation Storytelling. His final role with CBC was host of Up North, the afternoon radio program for northern Ontario. He left daily journalism in 2020 to focus on his literary career.

He currently lives in Sudbury, Ontario with his wife and two sons, where he’s working on the sequel to Moon of the Crusted Snow. To learn more about Waubgeshig Rice, please visit his ![]() website.

website.

I

“Aged Boreal Forest” by MIKOFOX ⌘ Reject Fear, Go Outdoors, Live Healthy is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

In the novel, Moon of the Crusted Snow, a First Nation community in northern Ontario deals with the sudden disappearance of communications and then power, severing their ties to the South. As winter approaches, many in the community realize they aren’t as prepared as they should be due to their reliance on technology and modern conveniences. As people struggle through the winter months, it becomes clear that the key to survival may be found in reconnecting, as a community, with the land.

Environmental Studies, Indigenous Studies, History, Law Studies, and Literature Studies

In the coming weeks, the temperature would drop and the snow would come. Soon after, the lake would freeze over and the snow and ice would be with them for six months. Like people in many other northern reserves, they would be isolated by the long, unforgiving season, confined to a small radius around the village that extended only as far as a snowmobile’s half tank of gas. (page 11)

Despite the hardship and tragedy that made up a significant part of this First Nation’s legacy, the Anishnaabe spirit of community generally prevailed. There was no panic on the night of this first blizzard, although there had been confusion in the days leading up to it. Survival had always been an integral part of their culture. It was their history. The skills they needed to persevere in this northern terrain, far from their original homeland farther south, were proud knowledge held close through the decades of imposed adversity. They were handed down to those in the next generation willing to learn. Each winter marked another milestone. (page 48)

1. Before reading the book, reflect on what land-based knowledge means to you. Ask this question again after reading the book. How has your understanding of land-based knowledge changed?

2. How do you feel connected to the land around you? How does the environment sustain you (mentally, physically, emotionally, spiritually)?

3. In your current context, how is your daily life shaped by the land and/or your environment, in big ways and small?

1

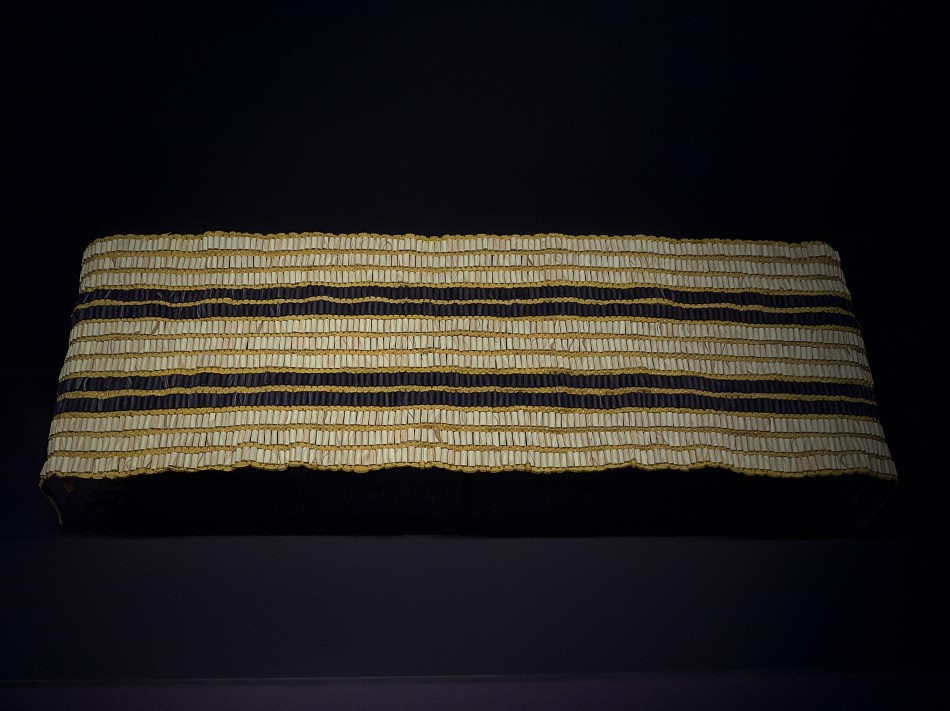

“Guswenta ‘Two Row’ Wampum Belt (Replica)” by keycmndr (aka CyberShutterbug) is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Treaties are the original agreements between Indigenous and settler peoples. One of the earliest agreements was the Two Row Wampum between the Haudenosaunee and the Dutch in 1613. Not all treaties were signed by the government in good faith and treaty relationships continue to evolve today as Indigenous nations seek to rightfully claim what has been denied to them. For example, the ![]() Robinson-Huron Treaty First Nations are currently involved in litigation to increase annuity payments.

Robinson-Huron Treaty First Nations are currently involved in litigation to increase annuity payments.

Not all land in Canada has been ceded through the treaty.

![]() We Are All Treaty People is a comprehensive module developed by Jean Paul Restoule. It shares about treaties from pre-contact to contemporary times and contains reflective questions and activities.

We Are All Treaty People is a comprehensive module developed by Jean Paul Restoule. It shares about treaties from pre-contact to contemporary times and contains reflective questions and activities.

The Government of Canada offers ![]() information about treaties as well as

information about treaties as well as![]() original treaty texts. These can be used as primary sources.

original treaty texts. These can be used as primary sources.

The Government of Ontario offers an ![]() interactive resource that allows you to click onto different treaty areas in the province. Type in your address and find what treaty land you live on.

interactive resource that allows you to click onto different treaty areas in the province. Type in your address and find what treaty land you live on.

1. How have Indigenous peoples been impacted by historic and modern treaties? How is this evident in the book?

2. How have non-Indigenous peoples been impacted by historic and modern treaties? How do non-Indigenous peoples benefit as Treaty peoples?

1. Ask students if they know the name of the traditional territory that they live on. This website can help students find that information, along with the traditional languages spoken in the area:![]() Native-Land.ca

Native-Land.ca

2. Find a First Nations community in northern Ontario, like where the book is based (hint: you can use the Ontario interactive treaty map shared above). Research the treaty negotiations for this community. Investigate the journey the community has taken from their ancestral grounds to where their reserve is now located. In what ways has their community been impacted?

2

“File:Winter-boreal-forest-Trondheim.jpg” by Orcaborealis is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

Indigenous peoples’ relationship to the land we now call Canada has existed for millennia. While colonization and modernity have impacted this relationship, there are individual and community-wide efforts of renewal and revitalization.

“But in just a couple of generations, a lot of people have moved away from winter preparations like hunting and gathering wood, and have become more reliant on the amenities that bring them closer to the world to the south. So when they lose many of these conveniences, it’s a sobering wake-up call to re-examine their roles and responsibilities to the land and their community as Anishinaabeg.

Part of it goes back to what I mentioned earlier about putting a different lens on post-apocalyptic experiences and why an Indigenous perspective is crucial to consider. Nations and cultures have survived since time immemorial on this land without the fragile luxuries we’re so dependent on today. If and when those things disappear, the answer to survival will be in the land, as it has always been. Also, a personal reason for driving this message home was to remind myself to reconnect with the land. I grew up on the rez with lots of land-based knowledge, but I’ve lost a lot of that since I’ve lived in cities for two decades now.”

Evan ate southern meats when he had to, but he felt detached from that food. He’d learn to hunt when he was a boy out of tradition, but also necessity. It was harder than buying store-bought meat but it was more economical and rewarding. Most importantly, hunting, fishing, and living on the land was Anishinaabe custom, and Evan was trying to live in harmony with the traditional ways. (page 6)

He would have liked to have kept the hide intact. If his dad and a couple of his cousins or buddies were with him, they could have loaded the whole moose onto a truck and done all the skinning and cleaning at home. There they could clean and eventually tan the hide to use for drums, moccasins, gloves, and clothing. (page 7)

The Assembly of First Nations is the national advocacy group for First Nations in Canada. They are also interested in ![]() Honouring the Earth.

Honouring the Earth.

The ![]() United Nations plays a role in supporting Indigenous peoples around the world in their pursuit of self-determination and land rights.

United Nations plays a role in supporting Indigenous peoples around the world in their pursuit of self-determination and land rights.

This source from ![]() Trent University’s Indigenous Environmental Studies and Sciences programs shares other relevant links about Indigenous connection to the land.

Trent University’s Indigenous Environmental Studies and Sciences programs shares other relevant links about Indigenous connection to the land.

This ![]() short doc by Ryan McMahon from the Canadian Broadcast Corporation’s Stories from the Land series shares about the last commercial net fishermen in Rainy Lake, found in northwestern Ontario.

short doc by Ryan McMahon from the Canadian Broadcast Corporation’s Stories from the Land series shares about the last commercial net fishermen in Rainy Lake, found in northwestern Ontario.

This ![]() short doc from the same series shares about the significance of corn soup to the Haudenosaunee.

short doc from the same series shares about the significance of corn soup to the Haudenosaunee.

1. The novel begins with Evan hunting a moose. In what ways is Evan connecting with his Anishinaabe identity when harvesting the moose?

2. On page 107, Justin Scott says that he knows how to live on the land. On page 124, Justin goes hunting with Evan, Dan, Isaiah, and Jeff. Compare and contrast Justin’s way of living on the land with Evan’s.

3. Identify examples of the ways in which characters use their land-based knowledge?

1. Evan remarks how hunting for meat is harder than buying it but it is more economical and rewarding (page 6). Elsewhere in the book, Dan and Evan tan a moose hide (page 21). ![]() This video shows the traditional way of harvesting deer by a member of the Lac Du Flambeau Band of Lake Superior Chippewa.

This video shows the traditional way of harvesting deer by a member of the Lac Du Flambeau Band of Lake Superior Chippewa.

Reflect on the ways that the characters in the book and person in this video provide for their family and community. Compare this to the ways that small-scale farmers approach agriculture, and then to large-scale farming.

2. Reflect on the cost of groceries in your own community. Identify the general cost of some produce, dairy, meat, canned goods, and household products. Conduct internet research on the cost of food in northern Ontario and into the far north. Compare the cost of living in each place. How do you think this impacts Indigenous well-being in northern communities?

3. Aileen urges Evan to learn about the medicines found on the land (page 147). In this video, Joseph Pitawanakwat discusses traditional medicines.

Find examples of modern medicines that come from the traditions of Indigenous peoples in Canada and around the world.

3

The Water Walker – Joanne Robertson

The Elders Are Watching – David Bouchard

Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants – Robin Wall Kimmerer

The Indigenous Fight for Environmental Justice, from Colonization to Standing Rock – Dina Gilio-Whitaker

No Surrender: The Land Remains Indigenous – Sheldon Krasowski

The Inconvenient Indian: A Curious Account of Native People in North America – Thomas King

II

“Broken land” by jlaguna is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

Colonialism is a prevalent theme throughout the novel. The lasting impacts of colonial policies and practices by the state, such as land theft, displacement, loss of Indigenous languages, and residential schools, are felt by every member of the community where this story takes place. The community’s relationship with the South, including characters that arrive in the First Nation community from the South, represents the broader colonial legacy in Canada.

Colonialism is a global phenomenon, but the impacts are not homogenous. In what is currently called Canada, Indigenous peoples, including First Nations, Métis, and Inuit, have been impacted by colonialism in all aspects of life. Therefore, the theme of colonialism has broad curriculum connections, not limited to the following: History, Literature Studies, Indigenous Studies, Law Studies, Sociology, and Anthropology.

“I wanted to portray Evan as a rez “everyman” who embodies the paradox of modern Indigenous life, like many of us who grew up in a First Nation do. Within just a couple of generations, culture and language are scrubbed from his community due to the brutal impacts of colonialism. Even though he didn’t endure the violence of residential schools himself, because his grandparents did, very little of his Anishinaabe identity was passed down to him. It’s the common intergenerational trauma of these terrible assimilative measures. Fortunately, he still has links to the old ways, and they become clearer and more important during this crisis. But basically, I wanted to convey that there are a lot of people like Evan, wanting to learn about being Anishinaabe but finding it hard to connect with those old ways even though they live immersed in an Indigenous community.”

“I think the truths about this country’s history are still emerging, and until there’s a more complete picture of the impact the formation of Canada continues to have on Indigenous people, reconciliation won’t happen. I’m not even totally sure what reconciliation means in the sense of a way forward, anyway. It means different things to different people. The residential school saga only really became common knowledge within the last decade. And even now there are people who deny its violent and merciless legacy. It’s frustrating to see those ignorant ideas and perspectives come to light.

And there are many more moments in recent history that aren’t understood by everyday Canadians. The Sixties Scoop only really made mainstream news in the last five or six years or so. Non-Indigenous people aren’t aware of treaty history and how those agreements predate Canadian confederation. There’s little awareness of the diversity of the cultures and languages of Indigenous nations on this land. The list goes on. Part of the design of settler colonialism that created this country was to keep people in the dark about all of these things.”

It was supposed to be a dry community. Alcohol had been banished by the band council nearly two decades ago after a snarl of tragedies. Young people had been committing suicide at horrifying rates in the years leading up to the ban, most abetted by alcohol or drugs or gas or other solvents. And for decades despairing men had gotten drunk and beaten their partners and children, feeding a cycle of abuse that continued when those kids grew up. It became so normal that everyone forgot about the root of this turmoil: their forced displacement from their homelands and the violent erasure of their culture, language and ceremonies. (page 44)

Somehow Evan had known that the cigarettes and free-flowing booze would lead back to Scott. Scott hadn’t been in the community long, but rumour had it that he was the man to go to if you’d run out of smokes or alcohol. He had somehow concealed a decent supply of vices in those hard cases he towed from the South. (page 131)

Our world isn’t ending. It already ended. It ended when the Zhaagnaash came into our original home down south on that bay and took it from us. That was our world. When the Zhaagnaash cut down all the trees and fished all the fish and forced us out of there, that’s when our world ended. They made us come all the way up here. This is not our homeland! But we had to adapt and luckily we already knew how to hunt and live on the land. We learned to live here. (page 149)

This short video provides a guide to appropriate language when referring to Indigenous Peoples in Canada.

The show ![]() First Contact follows six non-Indigenous Canadians with stereotypical views about Indigenous peoples. The group travels across Canada over 28 days to learn the truths of Indigenous experience in colonial Canada. The show has also faced some

First Contact follows six non-Indigenous Canadians with stereotypical views about Indigenous peoples. The group travels across Canada over 28 days to learn the truths of Indigenous experience in colonial Canada. The show has also faced some ![]() controversy for the ways it relies on Indigenous peoples reliving their pain to teach others. This tension presents an important reminder that seeking information from reputable sources is an important first step in learning about Indigenous peoples’ histories, cultures, and perspectives.

controversy for the ways it relies on Indigenous peoples reliving their pain to teach others. This tension presents an important reminder that seeking information from reputable sources is an important first step in learning about Indigenous peoples’ histories, cultures, and perspectives.

1. In what ways is Justin Scott a metaphor for colonizers and colonization?

2. Do you agree with Aileen when she says to Evan that their community has already experienced the apocalypse (page 149)? Justify your answer.

4

“Cree students and teacher in class at All Saints Indian Residential School, (Anglican Mission School)… / Élèves cris et leur professeure au Pensionnat indien de All Saints, (École missionnaire anglicane)…” by BiblioArchives / LibraryArchives is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Residential schools existed in Canada for over 150 years, preceded by other types of colonial institutions which attempted to extinguish Indigenous languages, cultures, and ways of being. Schools existed across the country, with children as young as five years old being removed from their family and community, to attend school for months, and sometimes years, at a time. These schools were mired by emotional, physical, sexual, and spiritual abuse, with many not surviving, as well as poor educational outcomes. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada completed extensive research and engagement with Indigenous communities to document this significant part of Canada’s history and published its final report in 2015.

(2:43) “A lot of communities like the one in this story are overcoming the negative, brutal impacts of being colonized, being displaced from their homelands and having children taken away and really being shamed out of their culture and being legislated out of their culture in many ways.”

(3:02) “There’s a healing process that is ongoing and I think that is prevalent in a lot of First Nations in Canada today. They are at some point in that healing journey. Some people are reclaiming the language, the culture, the traditions, hunting, fishing and aspects like that but they aren’t quite there.”

It had become protocol to open any community event or council meeting with a smudge. This protocol had once been forbidden, outlawed by the government and shunned by the church. When the ancestors of these Anishinaabe people were forced to settle in this unfamiliar land, distant from their traditional home near the Great Lakes, their culture withered under the pressure of the incomers’ Christianity. The white authorities displaced them far to the north to make way for towns and cities.

But people like Aileen, her parents, and a few others had kept the old ways alive in secret. They whispered the stories and the language in each other’s ears, even when they were stolen from their families to endure forced and often violent assimilation at the church-run residential schools far away from their homes. They had held out hope that one day their beautiful ways would be able to re-emerge and flourish once again. (page 53)

In this video, you can learn from Julie Pigeon, Turtle Clan, about smudging.

To learn about the history of residential schools please see the following websites:

![]() Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s Final Report

Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s Final Report

![]() National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation

National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation

![]() Where are the Children? Resource

Where are the Children? Resource

This ![]() Canadian Geographic resource uses Google Earth to explain residential schools in Canada.

Canadian Geographic resource uses Google Earth to explain residential schools in Canada.

This OER shares about the ![]() Shingwauk Residential School in what is called Sault Ste. Marie.

Shingwauk Residential School in what is called Sault Ste. Marie.

![]() Four Faces of the Moon is a stop-motion animation documentary by Amanda Strong. The documentary focuses on the impact colonization had on her family. The film is narrated in French.

Four Faces of the Moon is a stop-motion animation documentary by Amanda Strong. The documentary focuses on the impact colonization had on her family. The film is narrated in French.

![]() What is Reconciliation? From Facing History & Ourselves.

What is Reconciliation? From Facing History & Ourselves.

An interactive or media element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here: https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/moonofthecrustedsnow/?p=248

|

Youth |

Adults

|

|

|

Fiction |

|

|

|

|

|

| Non-Fiction | |

|

|

|

CBC’s Sunday Edition. |

|

5

Unsettling Canada: A National Wake-Up Call – Arthur Manuel & Grand Chief Ronald M. Derrickson

The Reconciliation Manifesto: Recovering the Land, Rebuilding the Economy – Arthur Manuel & Grand Chief Ronald M. Derrickson

III

“Naked” by TrotterFechan is licensed under CC BY 2.0

The Anishinaabe First Nation in the novel is strong and resilient although most of the members of this community are still dealing with the past and present effects of colonialism. Community in this story is also about the strength of family and cultural ties in a time of crisis.

Social Work, Anthropology, Sociology, Education, Literature Studies, Indigenous Studies

“I only ever wanted to tell this story from the perspective of the people in the community. It was really important to me to give the Anishinaabe characters the primary voice because I wanted to highlight their sense of community and relationship with the land as a means to survive.”

“It’s an homage to the everyday people on reserves across Canada. Those are the people that I don’t think get as much attention as they should because they’re laying the foundation or upholding the foundation of community just by being themselves and trying to live on the land in a good way and trying to bring culture back.”

“In the end though, despite all the death and despair this community experiences, they ultimately come together when they need to. And the spirit of survival is strong, thanks to everything they already endured as a result of colonialism. I believe in the resilience of Anishinaabe people and Indigenous nations as a whole.”

Gathering wood was a year-round process on the rez. People went into the bush to cut down spruce, oak, and maple to bring home for their own use or to sell. The band employed its own crew to provide wood for the elderly and others who needed help, and Evan brought any leftover wood home whenever he could. (pages 32-33)

Aileen was sitting at the kitchen table, sipping from the tea she had promised Evan. She still had an old wood cookstove in her kitchen and she could handle keeping it stoked, but she was too frail now to load the furnace in the basement. The main floor was toasty and it comforted Evan to know that Aileen was okay. He took off his jacket and placed it on the back of the wooden chair across from the elder. She put down her cup and smiled at him through her big glasses. “Everything okay down there?” she asked. Evan looked down at the full cup in front of him, then to hers. She had wrapped her thin, wrinkled fingers around the hot glass for warmth. The sleeves of her pink sweater were fraying at the end.

“Yeah, everything looks good. You got lots of wood still,” he replied. “Izzy will be by tonight to top it up.”

“I really appreciate you boys doing this for me. Chi-miigwech.”

“It’s nothing, Auntie. We’re happy to help.” (page 146)

1. Compare the community depicted in the novel to what you have seen or heard about First Nations in Canada. How are they similar and/or different? Where have some of your ideas about First Nations communities come from?

2. In what ways are members of this community equipped to deal with the aftermath of the blackout due to having been subjected to colonialism? In what ways are they challenged?

6

“Silouette” by Whenleavesfall is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

The concept of family in the novel extends beyond one’s immediate family members, to include community and relations with other-than-human-beings.

“We hear and see a lot of sensational stories in the mainstream media about Indigenous people living in communities across the country, and we rarely get a glimpse of those everyday experiences of maintaining a healthy family and surroundings. On the spectrum of contemporary Indigenous experiences, most Canadians are only exposed to extreme opposite ends. They either see Indigenous people as victims or tragic figures, or as exceptional triumphs who’ve overcome all odds (whatever that means). We rarely see the everyday people who make communities flourish. So in a crisis like in this book, Evan (or my real life friends and family back home) would be better suited to pull everyone through.”

… more rabbits would be snared through the winter. It was more than enough for his family of four, but he planned to give a lot of the meat away. It was the community way. He would share with his parents, his siblings and their families, and his inlaws, and would save some for others who might run out before winter’s end… (page 6)

He sat down and generously poured rye into the plastic cup in front of him, adding ice and ginger ale. Nicole mixed rum and Coke. Like many people in the community who still drank, they didn’t talk about it. It was easier to ignore all the sadness and despair that had come to their families because of alcohol if they just pushed it out of their minds. (pages 44-45)

To conserve precious resources, the families did most things together, rotating the hosting responsibilities. The idea was to save on firewood and food by living more communally. (page 171)

This ![]() video, Last Call Indian, is based on the life of Sonia Bonspille Boileau. She shares about the intersection of family, identity, community, and colonialism. Please be aware, based on language in the Indian Act, this film uses the word Indian.

video, Last Call Indian, is based on the life of Sonia Bonspille Boileau. She shares about the intersection of family, identity, community, and colonialism. Please be aware, based on language in the Indian Act, this film uses the word Indian.

1. Evan interacts with his father, Dan, tanning a hide on page 21 and we meet Evan’s brother on page 33. How, and why, might these relationships be different?

2. How do you describe Evan’s relationship with his parents, wife, and children? How does his Anishinaabe identity and community shape this relationship?

7

“Meeting room stencil graffiti” by clagnut is licensed under CC BY 2.0

The Chief and Band Council of the First Nation community in the novel play a large role in the way the community manages the blackout. Band Councils were imposed by the federal government through the Indian Act. Some communities today maintain a Band Council and traditional governance structure.

The band council and senior staff held their executive meetings here, and it was always where they hosted visiting dignitaries and potential business partners – a government official coming to tour the results of a funding announcement, or a corporation looking to invest in resource extraction. (pages 77-78 )

Connection to the world to the south could be disrupted easily, so the chief and council of the time had passed a resolution outlining a well-maintained and updated cache of goods that could keep upwards of five hundred people fed for at least two years. Few people besides councillors knew the extent of it or where it was stored, although its existence was generally known. (page 96)

The Band Council in the community where the book is set plays an important role in keeping the community organized. This link provides information about Bands and how they came to be. ![]() What is a Band?

What is a Band?

The Indian Act was first passed in 1876, consolidating pre-Confederation laws pertaining to “Indians.” ![]() The Indian Act is still relevant today.

The Indian Act is still relevant today.

In this video, ![]() The Indian Act explained, Bob Joseph discusses his book 21 Things You May Not Know About the Indian Act: Helping Canadians Make Reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples a Reality.

The Indian Act explained, Bob Joseph discusses his book 21 Things You May Not Know About the Indian Act: Helping Canadians Make Reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples a Reality.

![]() I am Indigenous – videos of seven Indigenous community builders in Ontario.

I am Indigenous – videos of seven Indigenous community builders in Ontario.

![]() The Pass System – This documentary looks at how policies put in place by the Indian Act gave powers to Indian agents to decide who could leave the reserve and for how long through a system of written permits.

The Pass System – This documentary looks at how policies put in place by the Indian Act gave powers to Indian agents to decide who could leave the reserve and for how long through a system of written permits.

8

I Sang You Down From The Stars – Tasha Spillett-Sumner

21 Things You May Not Know About the Indian Act – Bob Joseph

Black Water: Family, Legacy, and Blood Memory – David Robertson – With ![]() interviews on Unreserved, The Next Chapter, and Q with Tom Powers

interviews on Unreserved, The Next Chapter, and Q with Tom Powers

IV

“birch bark heart” by targut is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Indigenous concepts of gender and sexuality have been impacted by colonialism. Colonial attitudes towards gender and sexuality were imposed on Indigneous communities, in particular through the Indian Act and the Chief and Band Council system.

Gender Studies, History, Anthropology, Sociology, Education, and Law Studies

(11:03) “I think it’s important to really highlight the elder women in our communities who have really held things together despite all these other things that have happened.”

(35:27) “… Justin Scott, he embodies that toxic masculinity that is inherent in settler colonialism to begin with because he is very much an allegory for settling the land, overtaking it and exploiting it. At the core of that is the spirit of trying to conquer things and take things over, manipulate them … that’s the essence of toxic masculinity.”

(36:02) “On the other hand Evan, I think what I was trying to get at with him and his family is that there are healthy, functional families on reserves and these are the stories that we aren’t hearing enough of in the mainstream … and by and large, modeled after my own family. I grew up in a healthy and safe environment. That was also an antidote to toxic masculinity at the same time. The women in both my families, my father’s and mother’s, were by and large the leaders … that was normal and I don’t think we see it enough in art, in culture and the mainstream media.”

(38:38) “He’s young (referring to Evan), he’s in his early to mid-twenties, so he still has a lot to learn and I think I didn’t want to portray him as the hero because even though he does have an instrumental role in keeping order and keeping everyone fed, there’s this whole network of people behind him who are doing a lot of the heavy lifting too. He’s just a product of that, a product of a good sense of community and of people who are trying to do the right thing, look out for each other in the face of catastrophe.”

The boy was eager to join his father on his first hunt but that was still a few years away. Evan first went on an actual hunt with his own father when he was nine, after spending years learning about the land. He had shot his first buck that fall. They didn’t offer tobacco when they killed animals to eat back then – Evan only learned about that ceremony years earlier, when an elder took it upon herself to teach him and some of the other young people the old ways. (page 14)

Evan thought of Nicole at home, trying to prepare herself for the skills they would need if the power was gone for good while struggling to keep the children occupied. (page 147)

Conversation between Aileen and Evan

“What about your bazgim?”

“Oh, she’s tired, but she’s getting by. She really appreciates all the things you are teaching her about the old medicine ways, but she still gets stuck at home a lot with the kids while I’m out here doing stuff.”

“Well, you should make sure you spend more time with her. Go for a walk in the bush. When the spring comes, ask her to show you some of the medicines. She’ll know a lot now, if she remembers all the stuff from when I used to take her and all the young girls out there. It will be important if we don’t get any new supplies in from the hospital down south.” (page 147)

This CBC short doc, Wiigwaasabak: The Tree of Life, from Ryan McMahon shares about the relationship between art, community, culture, and family from the perspective of several Anishinaabe kwe in northern Ontario.

This short doc ![]() Zaasaakwe showcases the strong familial and social ties found within the community.

Zaasaakwe showcases the strong familial and social ties found within the community.

This video segment from ![]() Indigenous Concepts of Gender, a module within the massive open online course “Indigenous Canada” available from University of Alberta on Coursera, shares about Indigenous traditions and the impacts of colonialism.

Indigenous Concepts of Gender, a module within the massive open online course “Indigenous Canada” available from University of Alberta on Coursera, shares about Indigenous traditions and the impacts of colonialism.

![]() Gunn, B. L. (2017). Will the gendered aspects of Canada’s colonial project be addressed? Centre for International Governance Innovation. Retrieved from https://www.cigionline.org/articles/will-gendered-aspects-canadas-colonial-project-be-addressed.

Gunn, B. L. (2017). Will the gendered aspects of Canada’s colonial project be addressed? Centre for International Governance Innovation. Retrieved from https://www.cigionline.org/articles/will-gendered-aspects-canadas-colonial-project-be-addressed.

Ribbon skirts, created and worn by Indigenous women, are symbols of resilience and sacredness. In this video Myra Laramee explains the teachings and history of ribbon skirts. ![]() Skirt Teachings with Myra Laramee

Skirt Teachings with Myra Laramee

1. Evan Whitesky and Justin Scott represent two very different models of masculinity. Explain what you think these two different models are by using examples from the book.

2. Did the families portrayed in the novel seem different from what you expected a First Nation family might be like? If yes, what were those differences?

3. “The colonial process in Canada impacted Indigenous men and women differently” (Gunn, 2017, para. 10). Using examples from the novel, explain what you think the above statement means.

9

Highway of Tears: A True Story of Racism, Indifference, and the Pursuit of Justice for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls – Jessica McDiarmid

A Recognition of Being: Reconstructing Native Womanhood – Kim Anderson

Red River Girl: The Life and Death of Tina Fontaine – Joanna Jolly

The Final Report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG) reveals that persistent and deliberate human and Indigenous rights violations and abuses are the root cause behind Canada’s staggering rates of violence against Indigenous women, girls and 2SLGBTQQIA peoples. The two volume report calls for transformative legal and social changes to resolve the crisis that has devastated Indigenous communities across the country.

![]() Reclaiming Power and Place: The Final Report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG).

Reclaiming Power and Place: The Final Report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG).

V

“Trees Talk” by star_cosmos_bleu is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

There are over 70 Indigenous languages spoken in Canada today. As a result of colonization, there are concerns that many of these languages are going extinct. The author weaves Anishinaabemowin, the language of the Anishinaabe and one of the oldest Indigenous languages in North America, throughout the novel.

Languages and Linguistics, Education, Indigenous Studies, Anthropology, History, and Sociology

(2:16) “It was important to me as an Anishnaabe person to try to reflect some of the language to the best of my own ability. It was just about reflecting the day-to-day parlance that thrives in a lot of our communities … there is some decent knowledge still in a lot of places of Anishinaabemowin … it exists. It’s part of council meetings and family gatherings but just to have it live on the page, especially in a book, that is somewhat widely distributed, that a lot of non-Indigenous people will read, I just wanted them to know what the language looks like.”

“Within just a couple of generations, culture and language are scrubbed from his community due to the brutal impacts of colonialism. Even though he didn’t endure the violence of residential schools himself, because his grandparents did, very little of his Anishinaabe identity was passed down to him. It’s the common intergenerational trauma of these terrible assimilative measures. Fortunately, he still has links to the old ways, and they become clearer and more important during this crisis. But basically, I wanted to convey that there are a lot of people like Evan, wanting to learn about being Anishinaabe but finding it hard to connect with those old ways even though they live immersed in an Indigenous community.”

(24:43) “The Ojibwe that is in the book is sort of reflective of my own skills, like the things that I’m able to say, in my circles. My younger brother is a fluent speaker and he’s a teacher. So I consulted with him on a lot of those things. Grammar means a lot in Ojibwe, it is very technical and complicated.”

He still felt a little awkward, saying this prayer of thanks mostly in English, with only a few Ojibwe words peppered here and there. But it still made him feel good to believe that he was giving back in some way. Evan expressed thanks for the good life he was trying to lead. He apologized for not being able to pray fluently in his native language and asked for a bountiful fall hunting season for everyone. (pages 4-5)

Nicole closed the children’s book, Jidmoo Miinwaa Goongwaas, and kissed the top of Nangohns’s head. “There you go, my little star,” she said, switching from the Anishinaabemowin in the book to English. “Now you know about the squirrel and the chipmunk. You two stay put, I’ll be right back up.” (page 48)

The children were learning their language earlier and better than their parents had. Evan and Nicole has grown up in an era when Ojibwe wasn’t spoken much with the younger generation at home. It was only two generations before Nicole and Evan that speaking Ojibwe was punished at the church-run schools that imprisoned stolen children, and the shame attached to it lingered. Evan and Nicole had vowed to make things different for their kids. They had given them Anishinaabemowin names with pride – Maiingan meant “wolf” and Nangohns “little star.” (page 128)

Aileen was the last of the generation raised speaking Anishinaabemowin, with little English at all. She was one of only a few dozen left who could speak their language fluently. She remembered the old ways and a lot of the important ceremonies. She had more knowledge than everyone else about the traditional lives of the Anishinaabeg. (pages 146-147)

The crust of the snow he broke was thicker than his snowshoes. He kicked up frozen shrapnel each time he raised a foot. A fine powder lay underneath. The conditions made him think of the specific time of year. There’s a word for this, he thought, trying to remember with each high step across the hard snow. His knees raised as if to rev his mind into higher gear. He looked up to the lumpy clouds in the hope that the word would emerge like a ray of sunlight through overcast sky.

“Onaabenii Giizis,” he proudly proclaimed out loud. “The moon of the crusted snow.” (page 152)

![]() This article Language Warriors Needed: Miskwaanakwad on Anishinaabemonwin Revitalization is an interview between MUSKRAT Magazine writer, Erica Commanda, and Miskwaanakwad Manoominii, Anishinaabemowin language speaker from Wasauksing First Nation.

This article Language Warriors Needed: Miskwaanakwad on Anishinaabemonwin Revitalization is an interview between MUSKRAT Magazine writer, Erica Commanda, and Miskwaanakwad Manoominii, Anishinaabemowin language speaker from Wasauksing First Nation.

![]() The Ojibwe People’s Dictionary is a searchable, talking Ojibwe-English dictionary that features the voices of Ojibwe speakers.

The Ojibwe People’s Dictionary is a searchable, talking Ojibwe-English dictionary that features the voices of Ojibwe speakers.

![]() First Voices is a suite of web-based tools and services designed to support Indigenous peoples engaged in language archiving, language teaching, and culture revitalization.

First Voices is a suite of web-based tools and services designed to support Indigenous peoples engaged in language archiving, language teaching, and culture revitalization.

![]() Lorena Sekwan Fontaine on the question, Where do Indigenous Languages fit into Canada’s National Identity?

Lorena Sekwan Fontaine on the question, Where do Indigenous Languages fit into Canada’s National Identity?

1. What are the connections between the language(s) that you speak and your identity?

2. How would you feel if you were told that speaking English (or French) was forbidden and that you were to now speak in another language that is unfamiliar to you?

3. Many Indigenous languages are on the verge of extinction in Canada. Why is it important to ensure these languages survive? How can you ensure these languages are preserved and learned by future generations?

10

100 Days of Cree – Neal McLeod

Anishnaabemowin (Ojibew) Language Book – Gordon Shawanda

Book list of First Nation Language Readers

VI

“Symbol of the Anishinaabe People” by sturgill is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

In the book, some of the characters are more connected to their culture than others, however Anishinaabe culture permeates their modern community in the way they conduct community meetings, show respect for Elders, and in their connection to the land.

Indigenous Studies, Education, Cultural Studies, History, Anthropology, and Sociology

“Boozhoo, mino shkwaa naagweg kina wiya,” he began. “Good afternoon, everybody. Chi-miigwech for coming down here today. As you all know, we’ve been having some problems with power and satellite connections, so we’re here to give you an update. First though, I’d like to call up our elder Aileen to start this meeting with a smudge and a prayer.” (page 51)

But people like Aileen, her parents, and a few others had kept the old ways alive in secret. They whispered the stories and the language in each other’s ears, even when they were stolen from their families to endure forced and often violent assimilation at the church-run residential schools far away from their homes. They had held out hope that one day their beautiful ways would be able to re-emerge and flourish once again. (page 53)

The grey haze of the sage smoke hovered over the boardroom. The medicine continued to burn in the abalone shell on another table in the corner, pumping the healing aroma into the air. (page 77)

![]() Unreserved is a radio program for Indigenous community, culture, and conversation.

Unreserved is a radio program for Indigenous community, culture, and conversation.

![]() Tuesday Teachings from CBC’s Unreserved are short videos that share the knowledge of Indigenous communities.

Tuesday Teachings from CBC’s Unreserved are short videos that share the knowledge of Indigenous communities.

Bannock is a food that is mentioned in the novel.

![]() History of Bannock on CBC’s Unreserved

History of Bannock on CBC’s Unreserved

![]() Bannock, wild meat and indigenous food sovereignty on CBC’s Unreserved

Bannock, wild meat and indigenous food sovereignty on CBC’s Unreserved

Smudging is described in the novel (page 52). To learn about this ceremony, watch Julie Pidgeon share about smudging.

The title of the book references one of the thirteen moons of the year (moon of the crusted snow). Based on location and culture, different communities have different teachings for the moons.

This video describes the thirteen moons in Anishinaabemowin.

The ![]() OER Our Stories from Centennial College includes a section on the thirteen grandmother moons. You’ll notice some of the moons are different from the video above.

OER Our Stories from Centennial College includes a section on the thirteen grandmother moons. You’ll notice some of the moons are different from the video above.

11

The Mishomis Book: The Voice of the Ojibway – Elder Benton-Banai

Ojibway Heritage – Basil Johnson

A Digital Bundle: Protecting and Promoting Indigenous Knowledge Online – Jennifer Wemigwans

VII

The novel shares the story of a community living through a trying time, and what some characters, as well as the author, refer to as an apocalypse. The community and its leaders find ways to adapt and overcome their new circumstances. As the world moves through the COVID-19 pandemic, this section will evolve.

Anthropology, Education, Literature Studies, History, and Sociology

(11:10) “People who are living in poverty or poor housing or have limited access to secure food and so on, whose worlds have already ended and who are maybe on the brink of their personal worlds ending on a regular basis, like people in those situations understand just how tenuous life really is. I think that people from those backgrounds and with those experiences can be more adept to deal with something like this whereas people who are used to the comforts of modern technology and modern luxuries are having a bit of a harder time with it. So, if anything, I think it provides some perspective, especially for people who are from I guess the dominant core of society and, you know, hopefully they will understand just how loose of a grip we have on everything.”

(5:55) “Like the world we knew a month and a half ago isn’t going to exist anymore. We are not going back to that at all. We are going to emerge from this, whenever that happens in a new sort of era, in a new world altogether. So in some senses, yeah, I think that is an apocalypse. I think death, destruction, really world-ending violence is, I think, a key part of some of that. And that’s what Indigenous people have endured basically all over the world. You know, being displaced, having plagues set upon them, having children forcefully removed, you know, having culture made illegal and with violent consequences to practicing culture and that kind of thing. So I guess I can only really speak to it from an Indigenous perspective, in that it is already part of the indigenous experience, the ending of a world.”

(24:23) “I think the essential conversation people should be having is asking themselves and the people around them what their relationship is with the land that they live on and what’s really happening at this particular moment is this crisis has really highlighted the disconnect, not only between humans and the land that we live on, but also our abilities, you know, um, with all the panic-buying that’s been having happening. People are slowly starting to understand that they are reliant on food coming from elsewhere, whereas there is food in the land around them if they really worked hard enough and tried to make that connection.Right? I think people should be asking themselves, you know, what they’re able to do on the land and how they’re able to sustain it and how they’re able to work with each other to make a good life and a good community on the land.

Evan was surprised to see that the parking lot was packed. Trucks, cars, and snowmobiles were lined up sloppily in front of the store. He saw Nicole’s cousin Chuck lumber out carrying a cardboard box nearly twice as wide as his frame, and he was a big man. Evan watched Chuck put the box in the back of his truck, hop in the cab, and back out of there in a hurry. He got to the front door just as Isaiah was coming through with bulging plastic bags. He looked serious. (pages 59-60)

Walter rose to his feet and attempted to restore order. “Okay, okay, calm down,” he shouted into the racket. “Quiet!” His booming baritone hushed the entire gym. “Nobody’s getting any kind of special treatment. And we’re not gonna keep any food or supplies from anyone. This is a goddamn crisis! We have to act like a community. We’re going to support each other until this all gets sorted out.” (page 114)

Often, Aileen shared a teaching or an old story with the young men when they came to visit. Once in a while, someone would bring a group of children or teens to hear some old Nanabush stories or her memories of the old days. There had been no electricity in this community when she was a child and parents sometimes brought the young ones to her to remind them that life was possible without the comforts of modern technology. Now it was critical that they learn how the old ones lived on the land. (page 148)

This was Evan’s secret project: a shelter in the bush that he had begun the day after the food brawl. A backup, in case he and his family needed refuge from whatever turmoil might eventually consume his community. He had begun by chopping the long, straight narrow spruce trees that would be the pillars and stripping their bark. A few days later, he had sledded out the three thick canvases, one at a time. Each trip took a full morning. He came back a few days after that to dig out a fire pit and drape the tarps over the tipi frame. Here he was, weeks later, beginning to outfit the safe haven. (page 184)

1. What similarities can you draw between the book and real life events? Consider organizing these in a Venn diagram. How did the First Nation respond to upheaval? How have people responded in non-fiction contexts?

1

Dr. Kaitlyn Watson is a Euro-Canadian settler living on Anishinaabe homeland, Williams Treaty Territory. She is currently a Faculty Development Officer in the Teaching and Learning Centre at Ontario Tech University and regularly teaches Bachelor of Education and graduate education courses at universities across Ontario. Kaitlyn’s pedagogical and research interests focus on Indigenous-settler histories and decolonization. Kaitlyn is a secondary school qualified educator licensed by the Ontario College of Teachers.

Dr. Kaitlyn Watson is a Euro-Canadian settler living on Anishinaabe homeland, Williams Treaty Territory. She is currently a Faculty Development Officer in the Teaching and Learning Centre at Ontario Tech University and regularly teaches Bachelor of Education and graduate education courses at universities across Ontario. Kaitlyn’s pedagogical and research interests focus on Indigenous-settler histories and decolonization. Kaitlyn is a secondary school qualified educator licensed by the Ontario College of Teachers.

Dr. Anna Rodrigues is a settler of Portuguese descent who lives on the Traditional and Treaty Lands of the Mississauga Anishinabeg. She is an interdisciplinary educator and visual artist whose research explores how underprivileged communities amplify their voices through creative acts of resistance, whether it be in the form of art, literature, or media production. She is an Associate Graduate Faculty member in the Faculty of Education at Ontario Tech University.

With support from the OE Lab at Ontario Tech:

Sarah Stokes – Supervisor

Rebecca Maynard – OER Lab Assistant

Pranjal Saloni – OER Content Developer

Hasan Ahmad – OER Content Developer

Noopa Kuriakose – OER Content Developer

Abida Choudhury – OER Content Developer

Shreya Patel – OER Content Developer