Cover Image

1

1

Capacity to Connect: Supporting Students’ Mental Health and Wellness by Gemma Armstrong, Michelle Daoust, Ycha Gil, Albert Seinen, Faye Shedletzky, Jewell Gillies, Barbara Johnston, and Liz Warwick is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

© 2021 BCcampus

Capacity to Connect: Supporting Students’ Mental Health and Wellness was adapted from Capacity to Connect: Supporting Students from Distress to Suicide. © Vancouver Island University. It was shared under a memorandum of understanding with BCcampus to be adapted as an open education resource.

The Creative Commons license permits you to retain, reuse, copy, redistribute, and revise this book – in whole or in part – for free, providing the author is attributed as follows:

This adaptation includes changes and additions that are © 2021 by Jewell Gillies, Barbara Johnston, and Liz Warwick and are licensed under a CC BY 4.0 license.

A list of adaptations appears at the end of each chapter.

If you redistribute all or part of this book, it is recommended that the following statement be added to the copyright page so readers can access the original book at no cost:

Sample APA-style citation:

This resource can be referenced in APA citation style (7th edition) as follows:

Cover image attribution:

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-77420-120-6

Print ISBN: 978-1-77420-119-0

This resource is a result of the BCcampus Mental Health and Wellness Project funded by the Ministry of Advanced Education and Skills Training.

2

The web version of Capacity to Connect: Supporting Students’ Mental Health has been designed with accessibility in mind by incorporating the following features:

In addition to the web version, this book is available in a number of file formats including PDF, EPUB (for e-readers), MOBI (for Kindles), and various editable files. Here is a link to where you can download the guide in another format. Look for the “Download this book” drop-down menu to select the file type you want.

Those using a print copy of this resource can find the URLs for any websites mentioned in this resource in the footnotes.

While we strive to ensure that this resource is as accessible and usable as possible, we might not always get it right. Any issues we identify will be listed below.

There are currently no known issues.

The web version of this resource has been designed to meet Web Content Accessibility Guidelines 2.0, level AA. In addition, it follows all guidelines in Accessibility Toolkit: Checklist for Accessibility. The development of this toolkit involved working with students with various print disabilities who provided their personal perspectives and helped test the content.

3

Capacity to Connect: Supporting Students’ Mental Health and Wellness was developed under BCcampus’s Mental Health and Wellness Projects from funding by the Ministry of Advanced Education and Skills Training and guidance from an advisory group of students, staff, and faculty from B.C. post-secondary institutions. The purpose of the projects is to provide access to education and training resources for faculty and staff to better enable them to support post-secondary students with their mental health and wellness.

4

We gratefully acknowledge that this facilitator’s guide and the associated presentation have been adapted from Vancouver Island University’s training Capacity to Connect: Supporting Students from Distress to Suicide, which was developed by Vancouver Island University counsellors with input from Lyndsay Wells and Heather Owen, Vancouver Island Crisis Society. Recognition also goes to Heather Hyde, who developed the British Columbia Institute of Technology resource Identifying and Referring Students in Difficulty.

Thank you is extended to the B.C. Ministry of Advanced Education and Skills Training for their support, to BCcampus for their collaborative leadership, to the Mental Health and Wellness Advisory Group, and to the adaptation authors and collaborators whose knowledge and expertise informed this adapted version. See Appendix 3 for the list of authors, contributors, and advisory group members.

The authors and contributors who worked on this resource are dispersed throughout British Columbia and Canada, and they wish to acknowledge the following traditional, ancestral, and unceded territories from where they live and work, including Algonquin Anishinabeg Territory in Ottawa, Ontario; xʷməθkwəy̓əm (Musqueam), Skwxwú7mesh (Squamish), and Səl̓ílwətaʔ/Selilwitulh (Tsleil-Waututh) territories in Vancouver, BC; Syilx Okanagan Territory in Kelowna B.C.; Lekwungen/Songhees territories in Victoria, BC; and the Kʷikʷəƛ̓əm (Kwikwetlem), xʷməθkwəy̓əm (Musqueam), Skwxwú7mesh (Squamish), Stó:lō and Səl̓ílwətaʔ/Selilwitulh (Tsleil-Waututh) Nations in Port Moody, B.C. We honour the knowledge of the peoples of these territories.

5

Capacity to Connect: Supporting Students’ Mental Health and Wellness is an open educational resource (OER) and licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, unless otherwise indicated. You may retain, reuse, revise, remix, and redistribute this resource without permission. If you revise or remix the resource, it is important to include the copyright holder of the original resource and the authors of this adapted version.

6

This guide is for facilitators to present a two-hour workshop to post-secondary faculty, staff, or anyone wanting to learn more about supporting student mental health and wellness. It includes presentation notes, group and reflection activities, and scenarios to give participants a chance to practice. We invite you to augment the training with your own stories and examples.

Throughout the workshop there are notes and tips on ways to adapt the activities. There are also two resources (Handout 1 and Handout 2) that facilitators can give to participants at the end of the session. You may want to format these handouts according to your institution’s guidelines (e.g., colours, fonts, logos, etc.). You may also adapt the information in them to reflect the needs and concerns of the group you are addressing.

For a detailed breakdown of the workshop, see the Detailed Agenda.

This workshop also has PowerPoint slides that you can download at Preparing for the Session and use while giving the presentation. The slides can easily be formatted to meet your institution’s guidelines or slide deck templates. You can adjust the slides to fit the needs of your presentation. You may also want to add slides or create handouts about the contact information of counselling services, campus helplines, Indigenous student centres, and other services on your campus that support students.

This guide is for facilitators presenting a synchronous session either in-person or online, but anyone who wants to learn more about supporting student mental health can take this training online. You do not need to be a facilitator to discover, reflect upon, and use the information and resources provided in this guide. We welcome everyone and hope you find this guide of use in whatever way makes the most sense for you.

7

Student life is a time of change, uncertainty, and challenges. Many post-secondary students are living away from home for the first time and are learning to balance very busy academic schedules with managing finances, building their social circles, and figuring out their interests and future careers. The stress of post-secondary education is felt by all students at some point, and it can be overwhelming for some.

When the National College Health Assessment surveyed Canadian students in 2019, they found that students’ academic performance of was adversely affected by stress (42%), anxiety (35%), sleep difficulties (29%) and depression (24%) within the past 12 months. This same study found that 16% of students had seriously considered suicide over the prior year at least one time.American College Health Association. (2019). American College Health Association-National College Health Assessment II: Canadian Reference Group executive summary Spring 2019. Silver Spring, MD: American College Health Association. People in their late teens and early 20s are also at the highest risk of all age groups for mental illness; in these years, first episodes of psychiatric disorders like major depression are most likely to appear.Queen’s University. (2012). Report of the principal’s commission on mental health. https://www.queensu.ca/principal/sites/webpublish.queensu.ca.opvcwww/files/files/CMHFinalReport.pdf

Post-secondary institutions are taking these statistics seriously and working to address students’ mental health and find ways to better support them. Everyone has a role to play. As faculty and staff have frequent contact with students, we are often in a position to recognize when a student may be struggling. Responding with empathy and knowing how to connect a student to campus services and resources such as counselling services can be critical factors in supporting a student in distress.

This training is an introduction to what we can all do to support students’ mental health and well-being. The presentation starts with a discussion of mental health and wellness and looks at ways to promote resilience. The training then provides advice on how to recognize and respond to a student in distress and how to refer students to the other supports.

I

1

This section provides ideas and suggestions for facilitating both in-person and online training sessions. This includes:

A set of presentation slides is available to accompany both in-person and online workshops. These slides can be adjusted to meet the needs of your participants and formatted to meet your institution’s guidelines or slide deck templates. You can download the slides here: BCcampus, Capacity to Connect: Supporting Students’ Mental Health and Wellness [PPTX].

There are also two handouts available for download. Handout 1: Wellness Wheel, Handout 2: Supporting Students in Distress.

To prepare to facilitate this workshop, please consider the following:

You will need the following:

Facilitating conversations about mental health and well-being can be challenging. Participants likely bring many different experiences, assumptions, ideas, and worries about how best to support students who are struggling with these issues.

It’s important to create a space where people feel safe and supported so they share and listen to others with respect and empathy. This section offers ideas and tips for creating such an environment, but facilitators also have a time limit in which to present material. It’s important to keep an eye on the clock and know how, and when, to direct people’s attention to the next topic.

As mental health and wellness affects all parts of our lives, participants may bring up related issues or concerns. Below are some questions that might come up during the presentation, with suggestions for responses. The goal is to acknowledge people’s comments, thank them for their contribution, and point them to resources they may find helpful. Then the discussion can move back to the specific topic at hand.

An interactive or media element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://opentextbc.ca/capacitytoconnect/?p=36

Why isn’t this institution doing more to support students struggling with mental health and wellness?

Why do I have to be responsible for students’ mental health and well-being? We have counselling services for that.

I tried to help a student and it went badly.

What about the support for the mental health and well-being of faculty and staff?

This agenda provides suggested timings for activities, but facilitators should feel free to adjust these, including adding a short break as needed.

| Activity | Time |

|---|---|

Welcome

|

3 min |

Workshop Overview

|

2 min |

| Opening Activity | 4 min |

Wellness Wheel

|

15 min |

Mental Health Continuum

|

7 min |

Mental Health Statistics

|

5 min |

| Introduction to Three Rs Framework | 1 min |

First R: Recognizing

|

10 min |

Second R: Responding

|

20 min |

Third R: Referring

|

8 min |

Maintaining Boundaries

|

15 min |

Practice

|

20 min |

Summary and Conclusion

|

10 min |

2

This section describes how to welcome participants and prepare them to engage with the material. This includes:

An interactive or media element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://opentextbc.ca/capacitytoconnect/?p=35

These slides are available for use with this section of the presentation. For information about downloading presentation slides, see Preparing for the Session.

Welcome participants and open with a territory acknowledgement. If you’re unsure of your territory, the website Native-Land.ca is a helpful resource.

Territory Acknowledgement and Indigenous Ways of Knowing and Being

A meaningful territory acknowledgement allows us to develop a closer and deeper relationship with not only the land but also the traditional stewards and peoples whose territories we reside, work, live, and prosper in.

Acknowledging the territory within the context of mental health and well-being can open a person’s perspective on traditional ways of knowing and being, stepping out of an organizational structure and allowing participants to delve into their own perceptions, needs, and abilities.

Territory acknowledgements are designed as the very first step to reconciliation. What we do with the knowledge of whose traditional lands we are on is the next important step.

Some questions to consider as you acknowledge your territory:

Should your institution have an approved territory acknowledgement please use that to open the session; however, we invite you to consider how to make that institutional statement more personal and specific to you, in that moment and in the work you are about to delve into with your participants.

After the welcome, introduce yourself. You could ask participants to very briefly introduce themselves, or you may want to start the session with a short participant check-in as a way to invite people into a learning space. You could ask participants to share very brief introductions or do an online poll that asks people to choose the type of weather that matches how they are feeling. There are many different ways to have participants check in with themselves and the group, and we invite you to use questions and reflections that are meaningful to you and the group.

Review the overall goal of this presentation: to help faculty and staff develop the knowledge, skills, perspectives, and confidence to support student mental health and wellness.

After participating in the presentation, participants will be able to:

Participants will leave this session with a clear understanding of their role in responding to students in distress and have basic tools for approaching and referring students to campus resources.

Suggest that as people engage with the presentation, they reflect and think about how the information might apply to situations they have already had with students, or situations that they can imagine coming up in their role as faculty or staff.

Encourage people to provide feedback and share their input during the discussions as this helps improve the learning opportunities.

Encourage people to jot down notes during reflection activities. Encourage them to ask questions if they have any questions during the session.

Let everyone know that after the presentation, they will have access to printable (PDF) handouts of a Wellness Wheel worksheet and a handout on how to respond to students in distress. If possible, have a handout with contact information of your institution’s support services for students.

If you are giving this session online, remind online participants that they can turn off their cameras and move around the room during the session. Ask them to be mindful of using the mute button to reduce noise in the online space.

Most importantly, invite people to do whatever they need to take care of themselves throughout the presentation. Acknowledge this may be a difficult topic for some and suggest that participants do what they need to in order to care for themselves. Remind people that everyone is human and is touched in some way by the topics discussed in the presentation. People should feel free at any time to pause, take a break, stretch, and ground themselves.

For example, if a participant needs to leave or if some people prefer not to share, it’s okay. For in-person sessions, you could suggest that if a participant does need to leave a session that they give a thumbs up as they go to let you know they’re okay. Tell everyone that if you don’t see a thumbs up, you’ll ask a colleague to look for the participant outside the session to make sure they are all right.

Also, remind participants that they can share at the level that they feel comfortable with. Suggest that if anything comes up in the session that feels too important or difficult to handle on their own, people shouldn’t hesitate to reach out to the appropriate services – a counselling office or an employee assistance program – to debrief or discuss it further.

Understanding the Role of Faculty and Staff

Because faculty and staff interact with students frequently, they are often in a position to recognize when a student may be in distress. Responding with empathy and knowing how to connect a student to campus services and resources such as counselling services can be critical factors in supporting students’ mental health and well-being.

However, it’s important to emphasize that staff and faculty are not expected to act as a counsellor and should never try to diagnose a mental health issue. There are services on campus or in the community that support students who are struggling or in distress.

To effectively support students who are struggling, faculty and staff do need to be aware of the signs and symptoms of mental health issues. This session is to clarify what faculty and staff can do to support students’ mental health and wellness.

II

3

An interactive or media element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://opentextbc.ca/capacitytoconnect/?p=44

These slides are available for use with this section of the presentation. For information about downloading presentation slides, see Preparing for the Session.

Brainstorming Activity

To open, ask people to jot down what they think of when they think of mental health and wellness. (If online, ask people to add one or two thoughts into chat.) Ask people to briefly share.

The Public Health Agency of Canada defines mental health as “the capacity of every individual to feel, think, and act in ways that enhance their ability to enjoy life and deal with challenges. It is a positive sense of emotional and spiritual well-being that respects the importance of culture, equity, social justice, interconnections, and personal dignity.”Public Health Agency of Canada. (n.d.). Mental health and wellness. https://cbpp-pcpe.phac-aspc.gc.ca/public-health-topics/mental-health-and-wellness

Mental health is essential to overall health and influenced by the many different factors. We can all work to restore our mental health and wellness.

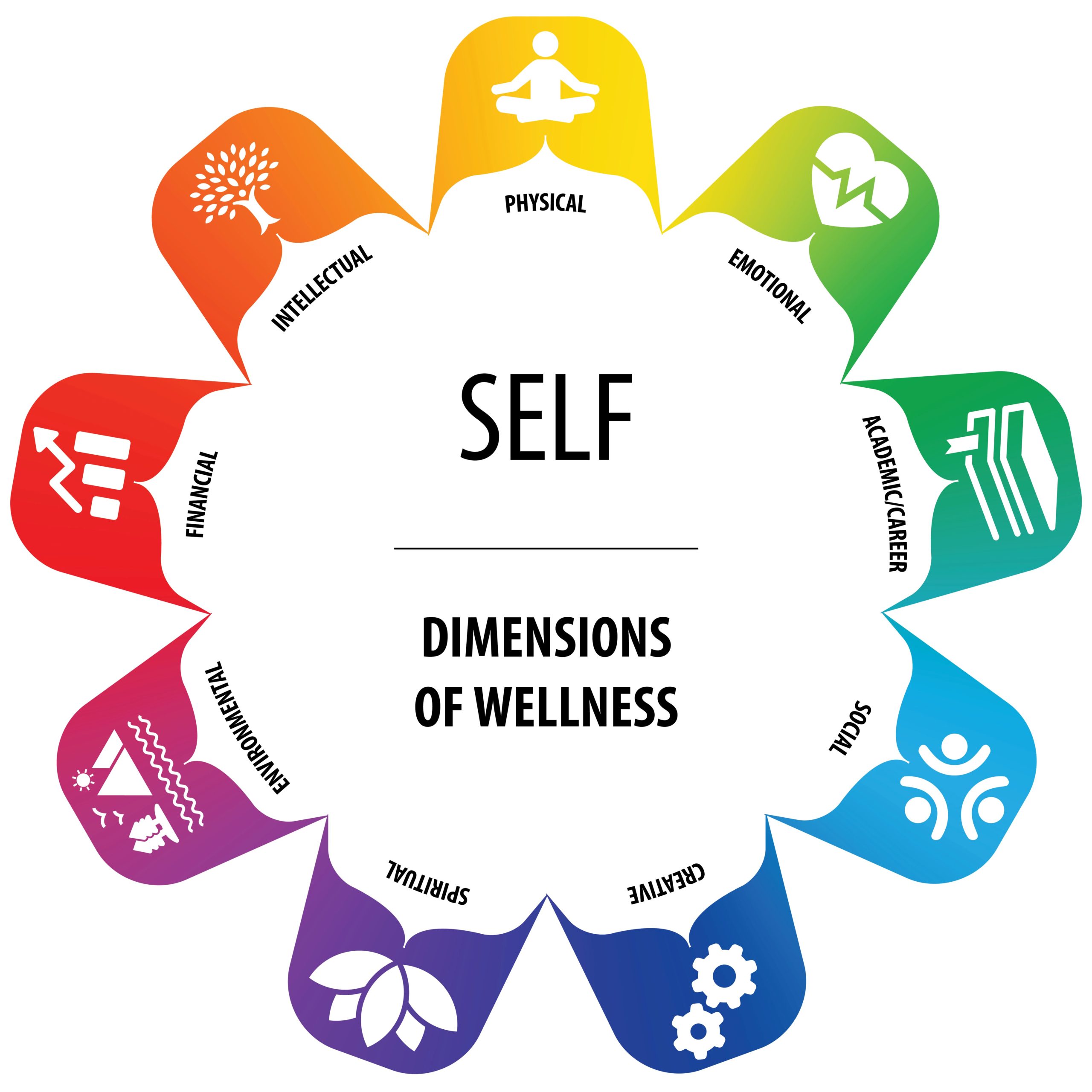

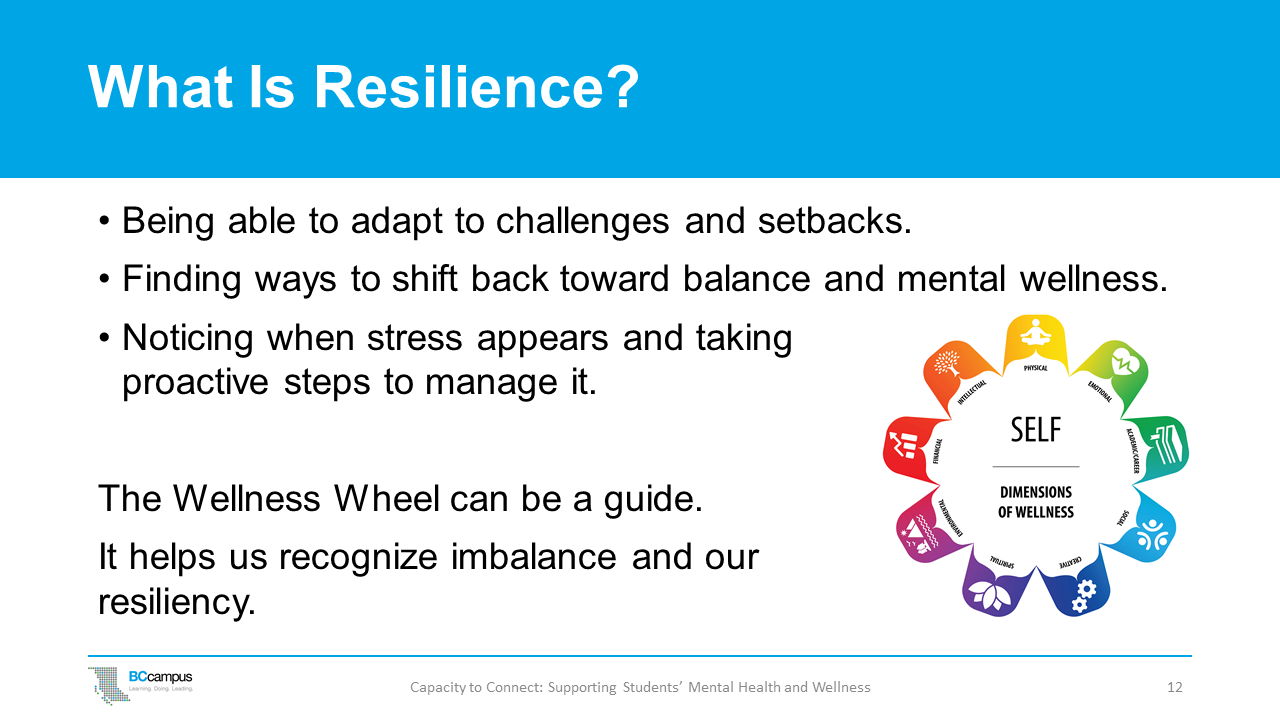

The Wellness Wheel aligns with Indigenous traditional practices that view individuals holistically, recognizing that wellness means being in a state of balance with the physical, emotional, academic/career, social, creative, spiritual, environmental, financial, and intellectual aspects of your life.

The Wellness Wheel is not a static concept, but a way of viewing the many dimensions that support wellness. There are things we can all do as individuals to improve our own mental health and well-being, and how we manage our wellness is an ongoing reflective practice.

The Wellness Wheel helps us to see what aspects might be falling in and out of balance in our lives. We can try our best to be flexible and respond to aspects of well-being that may need additional care or attention. Using the concepts in the Wellness Wheel can help us visualize our journey and assist in not only mitigating stressful circumstances, but also in recognizing areas of our lives in which we are thriving.

An interactive or media element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://opentextbc.ca/capacitytoconnect/?p=44

The following dimensions make up this Wellness Wheel:

Physical wellness: Taking care of your body through physical activity, nutrition, sleep, and mental well-being. For example:

Emotional wellness: Making time to relax, reduce stress, and take care of yourself. Paying attention to both positive and negative feelings and understanding how to handle these emotions. For example:

Academic/career wellness: Expanding your knowledge and creating strategies to support continued learning. For example:

Social wellness: Taking care of your relationships and society by building healthy, nurturing, and supportive relationships and fostering a genuine connection with those around you. For example:

Creative wellness: Valuing and actively participating in arts and cultural experiences as a means to understand and appreciate the surrounding world. For example:

Spiritual wellness: Taking care of your values and beliefs and creating purpose in your life. For example:

Environmental wellness: Taking care of what is around you. Living in harmony with the Earth by taking action to protect it and respecting nature and all species. For example:

Financial wellness: Learning how to successfully manage finances to be financially responsible and independent. For example:

Intellectual wellness: Being open to exploring new concepts, gaining new skills, and seeking creative and stimulating activities. For example:

Resilience means being able to adapt to life’s challenges and setbacks. When something is out of balance in our lives or we’re experiencing stress, resilience helps us to shift back toward balance and mental wellness. It’s the ability to adapt to difficult situations and it can help protect us from various mental health issues, such as depression and anxiety. Resilience isn’t about avoiding or ignoring challenges in life; rather, it’s noticing when stress appears and taking proactive steps to manage the stress and pressure.

The Wellness Wheel can help us recognize what might be causing stress or pressure in our lives. It also reminds us of our own resilience and strengths; while we may be struggling in one area, we may be doing well in many other areas.

Traditional Healing Practices

In many Indigenous cultures across Turtle Island (what we now call North America), Indigenous Peoples have used natural resources as a source of healing and ceremonial medicine since time began. These traditional healing practices are ways many Indigenous people restore balance and build resilience.

Below is one perspective on maintaining balance and wellness from Kwakwa̱ka̱’wakw culture. You can share this with your group or consider reaching out to Indigenous Elders or Knowledge Keepers in your community to learn more about local traditional healing practices that you could share with participants.

In my culture, we use the roots of a yarrow plant steeped in hot water to make tea to soothe stomachaches, headaches, colds, and diarrhea. We steam cedar branches in a pot on the stove to help with respiratory distress. We burn sage to smudge and cleanse ourselves, our space, or items of negative energies or spirits. When we have painful or negative emotions or when grief, sadness, or loss overwhelms us, we are taught to go back to the land, to go back to the water, to reconnect with the universe’s life force. Doing this through ceremony can be simple or elaborate; we can do this in private or within a trusted community.

One way we refer to these medicines is as helpers. Water is a common helper many people use, going to a natural body of water and submerging themselves entirely so the water cleanses them head to toe. If you do not have access to natural bodies of water, stand in the shower – not a bath that you soak in, but a shower to let the water run over you. This can be a time to speak to your helper and share with it your burdens; tell it what is weighing you down and ask for the help you need, allowing all the negativity to flow off you with the water. End with words of gratitude for the support of that helper.

As each Indigenous community has its own sacred connections to its territory and the medicines and plants that thrive there, we encourage you to seek out Knowledge Keepers in your area to learn more. Observe protocol by approaching the Elder or Knowledge Keeper with deep respect and an offering of tobacco (loose tobacco as it comes in the pouch from any general store is sufficient) while asking them to share with you what their traditional helpers may be. Not all ceremonial or cultural knowledge can be shared freely with people outside the community, as some sacred knowledge is kept for the community alone. But what can be shared will be shared with a good heart, as it helps all peoples come together in harmony.

—Jewell Gillies is Musgamagw Dzawada’enuxw of the Kwakwa̱ka̱’wakw Nation (Ukwana’lis, Kingcome Inlet, B.C.).

Small Group Activity

Divide the participants into small groups and ask each group to consider one or more aspects of the Wellness Wheel to discuss:

4

This section looks at the difference between mental health and mental illness and introduces the Mental Health Continuum, which illustrates how we can all move from healthier to more disrupted levels of functioning and back.

This section also looks at marginalized groups that are at higher risk of experiencing mental health challenges and face greater barriers to getting help.

An interactive or media element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://opentextbc.ca/capacitytoconnect/?p=51

These slides are available for use with this section of the presentation. For information about downloading presentation slides, see Preparing for the Session.

Mental health is a term that is often used interchangeably with mental health issues or mental illness, but they are not the same.

As we discussed, mental health is the capacity of every individual to feel, think, and act in ways that enhance their ability to enjoy life and deal with challenges.

Mental health issues refer to diminished capacities – whether cognitive, emotional, attentional, interpersonal, motivational, or behavioural – that interfere with a person’s enjoyment of life or adversely affect interactions with society and environment. Feelings of low self-esteem, frequent frustration or irritability, burnout, feelings of stress, or excessive worrying, are all examples of common mental health problems.Stephens, T., Dulberg, C., & Joubert, N. (1999). Mental health of the Canadian population: A comprehensive analysis. Chronic Diseases in Canada, 20(3): 118–126. Most people will experience mental health issues like these at some point in their life.

Mental illnesses are conditions that affect a person’s thinking, feeling, mood, or behaviour, such as depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), bipolar disorder, or schizophrenia. Such conditions may be occasional or long-lasting (chronic) and affect someone’s ability to relate to others and function each day.

Mental health is more than the absence of mental illness. It includes our emotional, psychological, and social well-being. It is influenced by many factors, and it affects how we handle the normal stresses of life and relate to others.

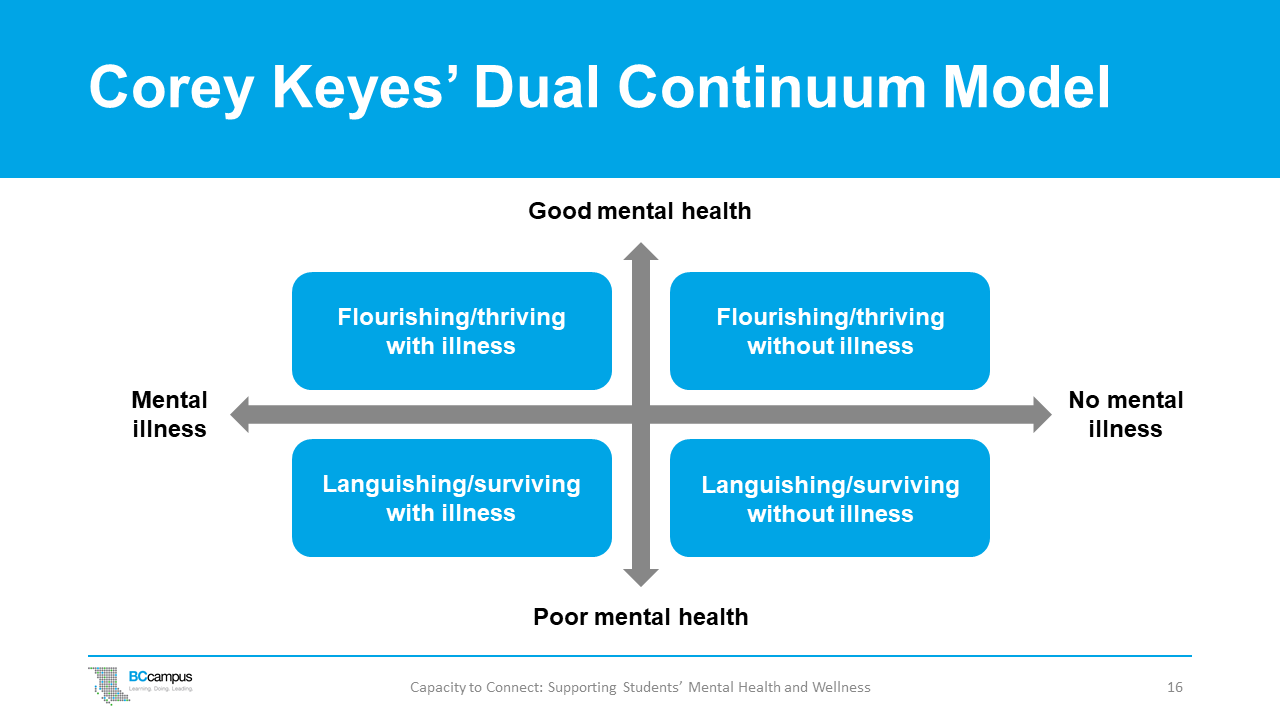

A person diagnosed with a mental illness can have good mental health and be flourishing and thriving. Likewise, a person can be languishing or experiencing poor mental health and not be diagnosed with a mental illness. The Corey Keyes Dual Continuum Model illustrates this.

An interactive or media element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://opentextbc.ca/capacitytoconnect/?p=51

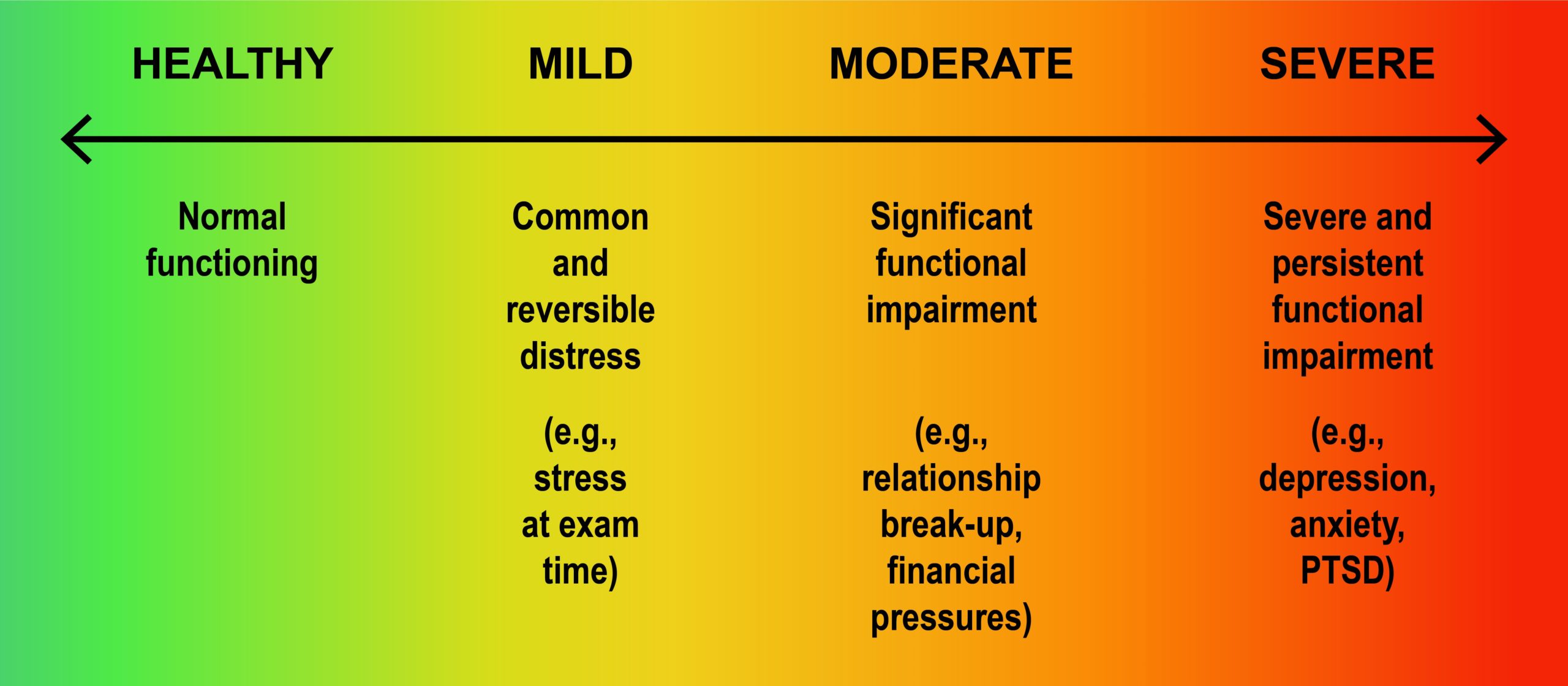

The Mental Health Continuum is another way to think about mental health. All of us have a mental health life; we all experience changes in our mood, changes in our level of anxiety – from life stressors or from crises – and those changes can be considered on a spectrum or a continuum. On this continuum, we can move from healthier to more disrupted levels of functioning and back. At each level, there are resources to promote health and reduce disruption.

On one end of the continuum, we have times when our health is good, we can cope with whatever comes our way, and we can do the things we need or want to do. We would describe that as healthy functioning. Thinking back to the Wellness Wheel, this is when everything is mostly in balance on the wheel or in our lives.

There are moments in our lives when we have what we call predictable or common stress. These experiences of stress are to be expected at times in our lives – they may be common and reversible, and they are usually temporary, such as the stress students experience during exam time. Students can maintain hope that when it’s all over, they’ll likely feel a lot better – the stressor will come to end and there is usually some relief.

We all have times when we feel down or stressed or frightened. Most of the time those feelings pass. Sometimes a person may just need someone to talk to and to be reminded that they are resilient and have other strengths, even though they may be struggling in one part of their life.

The next level is moderate disruption, which signifies more severe impairment to one’s mental health. Here the disruption is becoming more serious, and it is affecting other parts of a person’s life and their ability to function. A relationship break-up or financial pressures could cause more moderate disruption. On the Wellness Wheel, several areas of wellness are impaired and there is a more serious imbalance.

Severe disruption is when a person is unable to cope on their own because of significant and persistent functional impairment. They may need to take time off, and to seek professional help from a counsellor, doctor, or the hospital because of a mental illness such as anxiety, depression, or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

When we talk about mental health, we also need to be aware of factors like race, sexual orientation, social class, age, disability, and gender and the unique life experiences and stressors that accompany them. Some students face inequality, discrimination, and violence because of their race, gender orientation, or disability. These unique and specific stressors impact mental and physical health, and these students often experience greater mental health burdens and face more barriers to accessing care.

By providing a culturally safe environment, we can all play a role to ensure that each student feels their personal, social, and cultural identity is respected and valued.

Both undergraduate and graduate international students are often under a lot of pressure and the stakes are often very high for them. Their tuition is expensive, they’ve travelled a long way to attend a post-secondary institution in B.C., and they feel a lot of pressure to do well academically. They may be struggling to adjust to a new culture or learn English, and they may be missing home, family, and friends. The understanding of mental health and wellness differs between cultures, and international students may have a different understanding of how mental health impacts academic performance, and they may not be aware of the support systems available to them when they arrive.

Indigenous students may be struggling as they adjust from living in a community where they are surrounded by family and neighbours who share the same culture and spiritual beliefs to living in an urban academic setting. They may be the first generation to pursue post-secondary education, and they may be missing their home, family, Elders, and community. The impact of residential schools and other colonial policies have created ongoing adversity for Indigenous people, and there is evidence that this has created intergenerational trauma. Many Indigenous students may also lack trust in educational and health care institutions because of the negative or traumatic experiences they or family and friends have experienced in the past.

People who are LGBTQ2S+ (lesbian, gay, bi-sexual, transgender, queer, Two-Spirit) are at a much higher risk than the general population for mental health disorders, substance abuse, and suicide.U.S. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. (n.d.). Healthy people 2020: Lesbian, gay, and transgender health. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/lesbian-gay-bisexual-and-transgender-health Homophobia and negative stereotypes about being LGBTQ2S+ can make it challenging for a student to let people know this important part of their identity. When people do openly express this part of themselves, they worry about the potential of rejection from peers, colleagues, and friends, and this can exacerbate feelings of loneliness. Their health needs may be unique and complex, and health care settings can feel unsafe or uncomfortable for some.

Many students live with some form of physical, cognitive, sensory, mental health, or other disability. Students of all abilities and backgrounds deserve post-secondary settings that are inclusive and respectful. Unfortunately, many institutions are not designed to fully support people who need extra accommodation, and students with a disability frequently encounter accessibility challenges and extra barriers to achieving academic success. In addition to navigating the complex environment of a post-secondary institution that is not set up for them, students with a disability also often have to combat negative stereotypes, bias, and discrimination. These many extra challenges can take their toll on mental health.

Black, Indigenous, and other racialized students have likely faced racism and discrimination multiple times throughout their lives. Racism can encompass a range of words and actions, from the overt racism of violence or slurs to microaggressions (everyday, subtle interactions that demean or put down a person based on their race). Sometimes microaggressions are not intentional, but they can still be very harmful, and they are a form of racism that many students experience. These repeated negative interactions can be overwhelming at times, especially in post-secondary spaces where a student could reasonably assume they would be free from any form of bullying, harassment, or discrimination.

Racism and discrimination in various forms can have a significant impact on a student’s mental health and can lead to increased risk of depression or suicide, increased levels of anxiety and stress-related illnesses, and post-traumatic stress disorder.

Reflection Activity

Ask participants to think about the students they work with and consider the stresses that may be specific to certain groups.

5

This section provides general statistics on mental health in Canada as well as specific information about young adults.

It includes suggestions about finding and using statistics that best reflect the lived experience of your institution’s students, faculty, and staff.

An interactive or media element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://opentextbc.ca/capacitytoconnect/?p=56

These slides are available for use with this section of the presentation. For information about downloading presentation slides, see Preparing for the Session.

Mental illness is common and in any given year, one in five people will experience a mental health problem or illness.Mental Health Commission of Canada. (2012).Changing directions, changing lives: The mental health strategy for Canada. Calgary: Author. This means that if we count all of our friends, family, associates, people we work with, students in our classrooms, or even ourselves, we’re going to encounter a significant number of people who have a mental health problem or illness.

People in their late teens and early twenties are at the highest risk for mental illness; in these years, first episodes of psychiatric disorders like major depression are most likely to appear.Queen’s University. (2012). Report of the principal’s commission on mental health; Mental Health Commission of Canada. (2012). Changing directions, changing lives: The mental health strategy for Canada. Calgary, AB We know that mental health problems actually create more lost time from work and more lost pleasure in life than any physical health conditions.Canadian Psychological Association. (2006). Out of the shadows at last: Transforming mental health, mental illness and addiction services in Canada: A review of the final report of the Standing Senate Committee on Social Affairs, Science and Technology; Warren Sheppell Research Group. (2005). Workplace mental health indicators: An EAP’s perspective. https://www.shepellfgi.com/EN-US/AboutUs/News/Research%20Report/pdf/ir_mentalhealthindicators_enreport.pdf Mental health problems can be hugely disabling.

According to the Mental Health Commission of Canada, only one in three people (and only one in four children or youth) who experience a mental health problem or illness say that they have sought and received services and treatment. This means a lot of people who need treatment and support are not seeking help.

The National College Health Assessment collects data related to health and health behaviours of post-secondary students across Canada and the U.S. In 2019, the study of Canadian students found that over the prior year at least one time:American College Health Association. (2019). American College Health Association-National College Health Assessment II: Canadian Reference Group, executive summary spring 2019. Silver Spring, MD: American College Health Association.

Pursuing a post-secondary education is often a demanding and stressful time. These stressors can play a role in a student’s mental well-being and contribute to increased risk for mental health problems.

You need to give participants only a few statistics to illustrate that mental health issues are prevalent. There may be statistics on student mental health at your institution that you can use. Check with counselling services, student services, or Indigenous student services to see if they have statistics specific to your student population.

As you select and present statistics, you might want to consider using:

The arrival of COVID-19 upended the functioning of post-secondary institutions around the world. This created new challenges and stresses for students, faculty, and staff, as well as the larger community. While the pandemic will end, there are other global factors, such as the environmental crisis, that have a great impact on students’ mental health; you may want to find statistics on this.

If you want to address the stressors of COVID-19, here are some statistics about the effect it’s having on mental health.

From the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, Statistics Canada reports:Statistics Canada. (2020, May 27). Canadian’s mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Daily. https://www150.stacan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/200527/dg200527/dg200S27b-eng.htm

Also, in a May 2020 a Canadian Alliance of Student Associations study of 1,000 post-secondary students found the following:

Reflection Activity

Notice for yourself, do any of those statistics surprise you?

What thoughts have come up for you so far as you think about the prevalence of mental health issues?

III

6

An interactive or media element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://opentextbc.ca/capacitytoconnect/?p=62

These slides are available for use with this section of the presentation. For information about downloading presentation slides, see Preparing for the Session.

The Three Rs Framework – recognize, respond, refer – is an important way that we can support students. The first R is recognize. How do we recognize when someone is distressed and struggling? Thinking about your students and any times you might have been concerned about them, what are some signs you have noticed that they may be experiencing distress, which we define as more than predictable day-to-day stress? What did you notice? (Make the key point: the main sign is a change in a student’s presentation.)

Students often give us clues about the state of their wellness through either their words, body language, or actions. What are some signs of distress that you’ve noticed in students?

Either share the slide “Recognizing Signs of Distress” or write “Academic, Behavioural, Physical, Emotional” on the board and invite participants to share signs of distress that they’ve noticed in students. (For online sessions, ask participants to write their responses in chat.) You could also refer back to the exercise done earlier, where participants identified different behaviour changes they might see when there is an imbalance in the wheel.

Some possible signs that a student is not doing well include:

Academic signs

Emotional signs

Physical signs

Behavioural signs

Now let’s shift to talk a little more about suicide, which may be a concern for anyone trying to support students who are in crisis. A student could give warning signs such as:

For more information on signs that a person is considering suicide, see the IS PATH WARM tool, which is based on research from the American Association of Suicidology and used worldwide. It’s available on the Canadian Association for Suicide Prevention website. This tool helps you think about some of the signs that a student could show if they are thinking about suicide and need help. It is important to remember that faculty and staff are not in a position to diagnose and are not expected to act as a counsellor, but if they are aware of the signs, they can help refer the student so they get the help they need.

You now have a sense of some signs of distress that you may see in students, and you have all seen and experienced some of these before. This is the first step: Recognizing.

7

An interactive or media element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://opentextbc.ca/capacitytoconnect/?p=69

These slides are available for use with this section of the presentation. For information about downloading presentation slides, see Preparing for the Session.

The second R is respond. Start this section with a reflection activity.

Reflection Activity

Think of a time when you were mildly or moderately upset or distressed yourself. Perhaps think back to when you were a post-secondary student. Reflect on what you needed or hoped for at that time. What did you need or want from others? Please take a couple minutes to write some of your thoughts. (Give participants a few minutes.)

Then ask participants to share one of the things they needed or wanted from others when they were upset or distressed (remind them not to share the details of the event itself).

If you are presenting online, ask participants to put their answers in the chat box, and read the responses from chat.

Then ask them to share one thing that wasn’t or would not have been helpful. (If you are presenting online, ask participants to put their answers in the chat box.)

You have all had experiences with various responses when you were distressed. From your own life experience, you have developed an understanding of what is helpful that you can draw on when you are responding to students. The responses you have identified as helpful are examples of an empathic response.

This short video from well-known sociologist Brené Brown demonstrates how to respond in a helpful, compassionate way – empathy in action. (Show the Brené Brown video or share the link in chat): Brené Brown on Empathy.

Video Reflection Activity

After the video, remind participants that there is not a script you need to follow, nor one way that will always work. The most important thing is to be yourself and to be authentic – and this can include being honest when you’re not sure what to say.

The role of an empathetic listener is not to “fix” the student or tell them how to respond. Instead it is to listen and try to help them find appropriate support. Your expression of concern may be a critical factor in saving a student’s academic career or life.

In many cases it’s not the things we have to say that make the difference, it’s the things that we allow the other person to say and get off their chest that will make room for more life-affirming options to come forth. Just being there, giving support, and offering a listening ear can help create a turning point for a student who is struggling.

When responding to students in distress, consider an appropriate balance of desire to help and provide solutions and respect for students’ autonomy and their own capacity.

Before you talk to a student, make sure you are in a private place to have the conversation. Here are some suggestions:

You don’t need to “fix” the student, and you are not expected to act as the counsellor. You can assist many students simply by listening and referring them for further help.

Ask the group: what comes up for you when you consider asking about suicide? Invite them to share (either in person or in chat for online) and address answers, which may include:

Validate all responses, reinforcing the notion that it is frightening to ask about suicide. Reinforce that one of the greatest fears most people have about asking is, what if a student says “yes”?

One concern that people often have is that if they bring up suicide and a student isn’t considering it, they may start thinking about it as an option. That is untrue. Asking about suicide will not put the thought into someone’s mind. It can give the person a sense of relief – for example, “Finally, someone has seen my pain” – or give them permission to open up further about something they have been keeping hidden.

If you do ask about suicide, it can be helpful to be open and direct in your questioning – this approach will convey a level of comfort. If a student says they are contemplating suicide, here are some ways to be helpful:

Reinforce that it isn’t the expectation that everyone ask about suicide. If a participant is still nervous or uncomfortable with the question, that’s okay. It’s okay to have limits. Within your role, the expectation is that you would help get the student connected to someone who will ask.

8

An interactive or media element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://opentextbc.ca/capacitytoconnect/?p=73

These slides are available for use with this section of the presentation. For information about downloading presentation slides, see Preparing for the Session.

Let’s talk now about the third R, referring students for further support. Often a few minutes of effective listening are enough to help a student feel cared about. If their distress is more significant and they are open to accessing more support, there are several services that can help. Knowing what these services are and how to contact them will help you in your role.

If you have a list with names and contact information for these services at your campus, share this information with participants.

Below are some of the services available at most campuses.

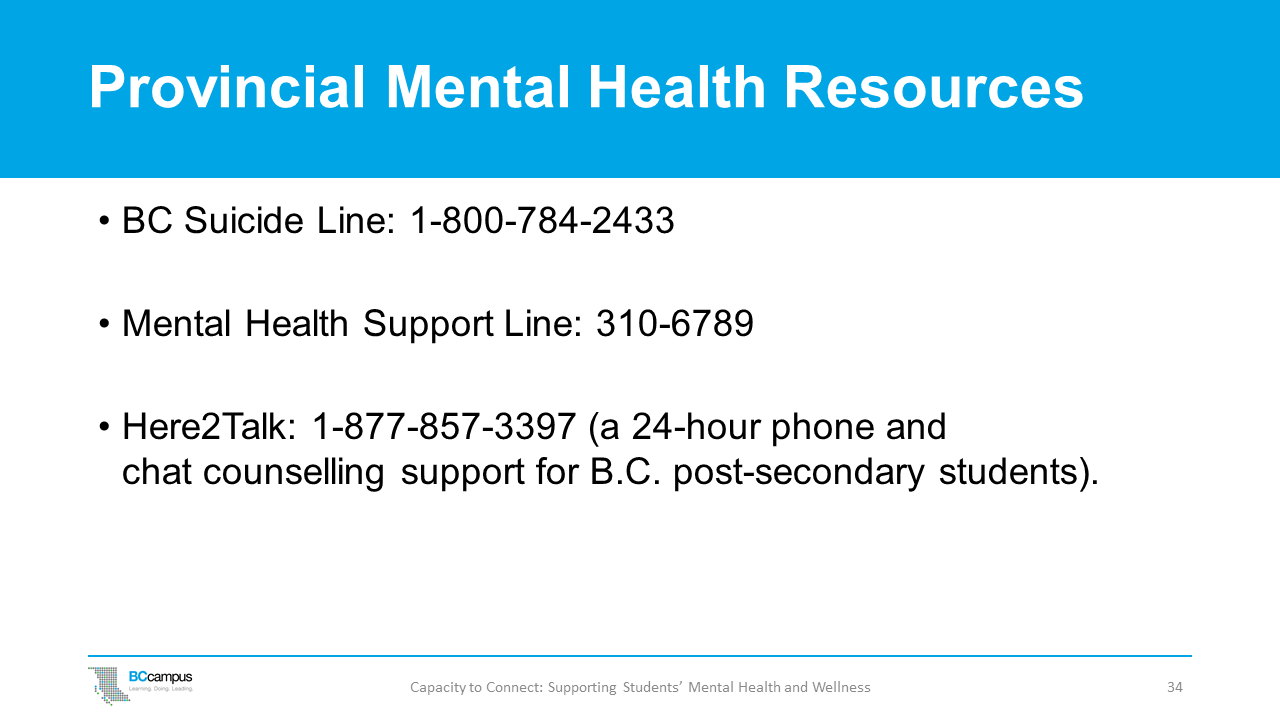

Some larger campuses have a crisis line for students. If your institution does not have this service, there are also provincial crisis and suicide lines that have 24/7 support. These crisis lines also provide support to anyone who is helping a student in distress and needs to talk to someone and debrief.

Some provincial supports include:

If You’re Concerned for a Student’s Immediate Safety

If it’s an emergency situation, such as the student has taken pills, is experiencing psychosis, or is a danger to themselves or others, call 911 and campus security.

If it’s not an emergency, but you are concerned, it can be helpful to offer to contact support services on the student’s behalf while they are with you. You may also offer to walk with the student to counselling services.

Sometimes a student may not want to see a counsellor or refuses help.

Your first step in these cases will be to consider safety: is anyone at risk of immediate harm, whether it’s the student or someone else? If so, share your concerns with a counsellor or someone who can help ensure safety. If a student expresses thoughts about suicide, you don’t have to carry that knowledge alone or assess the risk yourself – consult, refer, and if the risk is imminent, then contact emergency services.

If there is no risk of harm to anyone, keep in mind that ultimately it is the individual’s right to choose whether to seek help. Individuals are resilient and often come to their own solutions or find their own supports when they are ready.

Ensure you are supported! Talk to friends, family, other instructors, an Elder, or a counsellor to share your concerns and decide how to proceed.

Please be aware that if you refer a student to Counselling Services and are hoping to follow up to find out about the student, it is up to the student to give consent to release information.

Unless a student gives permission, faculty and staff won’t be notified of what has happened.

9

An interactive or media element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://opentextbc.ca/capacitytoconnect/?p=77

These slides are available for use with this section of the presentation. For information about downloading presentation slides, see Preparing for the Session.

When helping students, it is important to remember to maintain your own boundaries. Recognize what you can and can’t do, given the limitations of your role, and be clear with others. Refer students as appropriate and access your own support when needed.

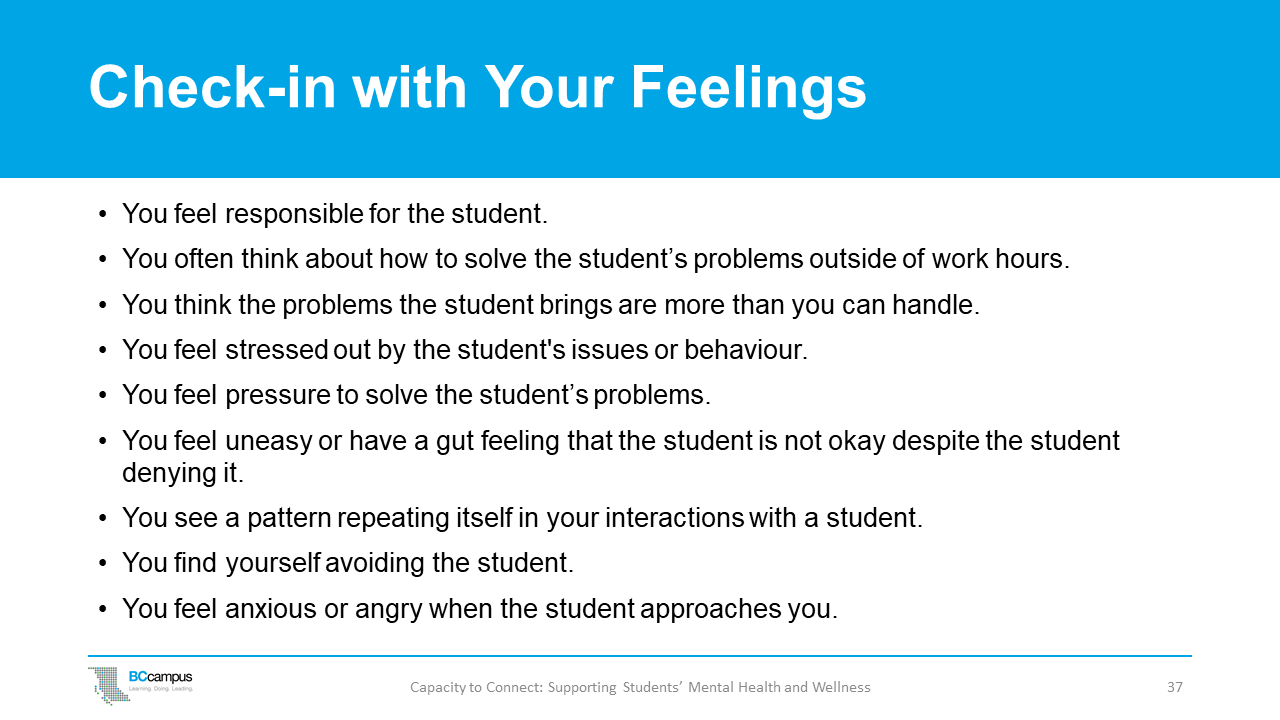

We’re going to consider a list of some feelings people might have as they try to support a student. These feelings may be signs that you are taking on too much and not maintaining boundaries. You may need to step back, consult, and take time for self-care. As you read this list, check in with your body and notice which of these resonate with you. They may remind you of an experience you’ve had with a student.

All of the above responses are common, and we can all likely relate to many.

We all have our limits of comfort challenged in different ways. When you notice any of these responses within yourself, it may be time to consult or refer.

We encourage you to consult with your colleagues, chairs, deans, or others whom you trust. Counsellors can meet with staff and faculty who are concerned about a student and are unsure how to handle the situation. You can also call a crisis line if you have serious concerns about a student. You are encouraged to consult when:

Brainstorming Activity

Ask participants to jot down a few ideas about how they can take care of themselves while still being open and available to offer support to students.

(If online, ask people to add one or two thoughts into the chat.)

IV

10

In this section, you’ll find examples of scenarios you can use, either in person or online, to provide opportunities for participants to practise using the knowledge they’ve gained.

These scenarios provide helpful tips on what to say to students in different situations. If you don’t have time for practice and discussion, try to allow some time to briefly review some of the responses. You can provide the scenarios as a handout or PDF (see Handout 2: Supporting Students in Distress).

Scenarios Pairs Activity

Ask participants to work in pairs to talk through some possible things to say to the student. Give the participants one of the six scenarios provided below to discuss together. (For online sessions, use breakout rooms.)

We’ve provided six scenarios of students who need support. Working in pairs, you can either role play or discuss together how you might respond and offer support to the student in this scenario. This is a chance to think through how to express your care and concern for the student and offer support and any further resources that seem appropriate. Also consider the perspective of the student, referring to the Wellness Wheel.

Questions to discuss as a group:

An important thing to remember is that you don’t have to have all the answers for students, and you don’t have to act as a counsellor. You can really support students by opening up a conversation, showing your care and respect, and inviting them to access support services.

The following six scenarios offer participants opportunities to think about and practise responding to situations of students in distress. People may also want to read and reflect on them in their own time.

Encourage participants to use these scenarios as starting points, not scripts, for discussions and continued thought about how we can respond with empathy to students while recognizing and honouring their strengths and capacity to achieve balance.

An interactive or media element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://opentextbc.ca/capacitytoconnect/?p=80

A student has just found out they failed an exam and starts to cry while talking to their instructor.

I can see that you are upset about the exam. I can hear the disappointment in your voice. You’ve said that you don’t feel that you can stay to attend the class, but I’m concerned about having you leave like this. I want to support you, but I have to teach this class right now. I wonder if you’d be willing to talk to a counsellor? It’s confidential. Would it help you to have someone from class or a friend walk over with you? Who will you ask? Let me call Counselling Services and tell them to expect you.

An Indigenous student comes into your office upset. They disclose to you that a close relative has just died unexpectedly, and they are stressed about how to ask their instructors for leave time from classes to go home for the ceremony and funeral. They explain to you that cultural protocols regarding the death of a family member are elaborate and can take up to a week or more to complete. They feel overwhelmed because they want to be home with their family and community, but they also have upcoming projects due in many of their courses. They express feelings of hopelessness during this interaction.

I am so sorry to hear about your loss; dealing with grief while trying to manage other responsibilities can be so challenging. I commend you for your resilience in such a difficult time; you are actively looking for support and that is important to honour in yourself.

Are there any cultural supports here that I can assist you in connecting with? Have you spoken with the staff in Indigenous Services? As for advocating for your needs with your instructors for leave time, I am happy to help you navigate that process – there are ways to make a request to your instructors for an extension on any class work or assignments. Shall we map out how you can email your instructors? Would you like me to connect you with Indigenous Services? I can introduce you to the staff there if you don’t already know them. I think they’ll be really receptive to supporting you in your request to the instructors as well and might have community or cultural supports that you can use.

An international student who is on probation has just failed an exam. The student fears they will be suspended and forced to go back to their home country, but they would be a disgrace to their family and they couldn’t face them. The student says that they can’t see any other option but to end it all.

I can see that you are upset about the exam. I can hear the disappointment in your voice and understand the fear about what will happen for you. When you say you might end it, I wonder if you mean you are thinking about suicide? I want to support you to be safe and to have a good outcome from this challenging time. I wonder if you’d be willing to talk to a counsellor? It’s confidential and I think it’s a wise thing to do. I’d like to walk over there with you.

If the student refuses, you could say, Another option is for us to call the crisis line together right now so you can talk with them and find out about some resources.

If the student says no, you could say, I care about you and am worried about you, so for me to feel comfortable, I need to have someone contact you to see how you’re doing and help support you.

A student presents as agitated and tearful. The student just found out they didn’t get a student loan. They talked to their parents, who are clear about not giving them money. They have paid their fees for courses but will not have enough money to get through the semester and are considered dropping out.

I’m sorry that you are having such a difficult time. I can see how upsetting this is to you and how much you want to take these classes. Have you spoken about your concerns with someone at the Financial Aid office? Are you aware of where they are located? Have you spoken to the chair of your department or to Academic Advising?

Do you have anyone to talk to about this? Perhaps you’d find it helpful to talk with someone in Counselling Services about making a plan for next steps. They are just down the hall. I can walk you there if you like. If you need support after hours you can also call the crisis line for support; here is their number.

A student who has disclosed to you in the past that they are transgender approaches you in tears. When you ask what is happening, they tell you that they were home with their family over the holiday break and they “came out” to their family. The family’s response was not supportive, and the student tells you their parents made hurtful and derogatory comments during the discussion. The student makes statements like “This is so difficult. I can’t keep going like this,” and ”I don’t know why I even try anymore; my own parents don’t love me or accept me for who I am.” I am tired of having to validate myself and who I am.” They share other more general feelings of loneliness and hopelessness.

Thank you for sharing this with me, I can appreciate this is such a difficult time for you and this has a significant impact on your well-being. While I don’t personally know what it’s like to identify in the LGBTQ2S+ community and not have the support or acceptance of your family, I can appreciate that this is a fundamentally important aspect of your well-being. Do you have any ideas on how I might be able to support you through this?

Have you connected with our Pride Centre or Student Union office on campus? I am happy to walk you over there now if you would like.

I have heard you make some statements around feeling hopeless and losing a sense of purpose in your life generally. Are you having any thoughts of self-harm or suicide? We have counselling services on campus that are confidential and free for all students; can I walk you down to their office so you can meet them and see if it would be a good fit to talk with one of their team?

If the student says no you, could say: Another option is for us to call the crisis line together right now so you can talk with them and find out about some resources.

I want you to know that I support you; you are a valued and important member of our campus community. I would like to support you in any way that I can to know that you are seen, valued, and celebrated here on campus.

You noticed a student in class who has been wearing the same clothes on a few occasions and looks somewhat dishevelled. They appear tense at times and other times they’ve seemed sleepy in class. Last class you walked by them and wondered if you smelled alcohol. They have been handing in their assignments but doing mediocre, and their grades have been dropping. The most recent assignment wasn’t handed in. You feel concerned but not sure if all of these observations are enough reason to act.

Thank you for meeting with me. I’ve been feeling concerned about how you are doing. I can see that you are motivated to be here as your attendance has been good. At the beginning you seemed enthusiastic about the material and discussions. However you seem tense and tired. Your grades have been going down and your last assignment was late. Last class I wondered if I smelled alcohol. I wonder how you are doing and I’m concerned you are going through a challenging time that is interfering with your ability to do as well as you can at school.

I’m glad that we are talking, although I feel that it’s beyond my scope/role to talk to you in detail about what’s happening. I’ve found that in times of challenge it’s helpful to get support for myself. Seeking help is courageous, not weak, and shows you are committed to working through the hard times. Do you have someone you can talk to? Have you considered accessing Counselling Services to talk or find out about resources? It’s confidential.

There are other supports on campus, and I wonder if you are aware of them and if anything would be useful to you. The campus website lists all of the student resources in one place: I’m happy to show it to you. The crisis line is also good to know about as they can provide support and ideas of community resources.

11

An interactive or media element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://opentextbc.ca/capacitytoconnect/?p=84

These slides are available for use with this section of the presentation. For information about downloading presentation slides, see Preparing for the Session.

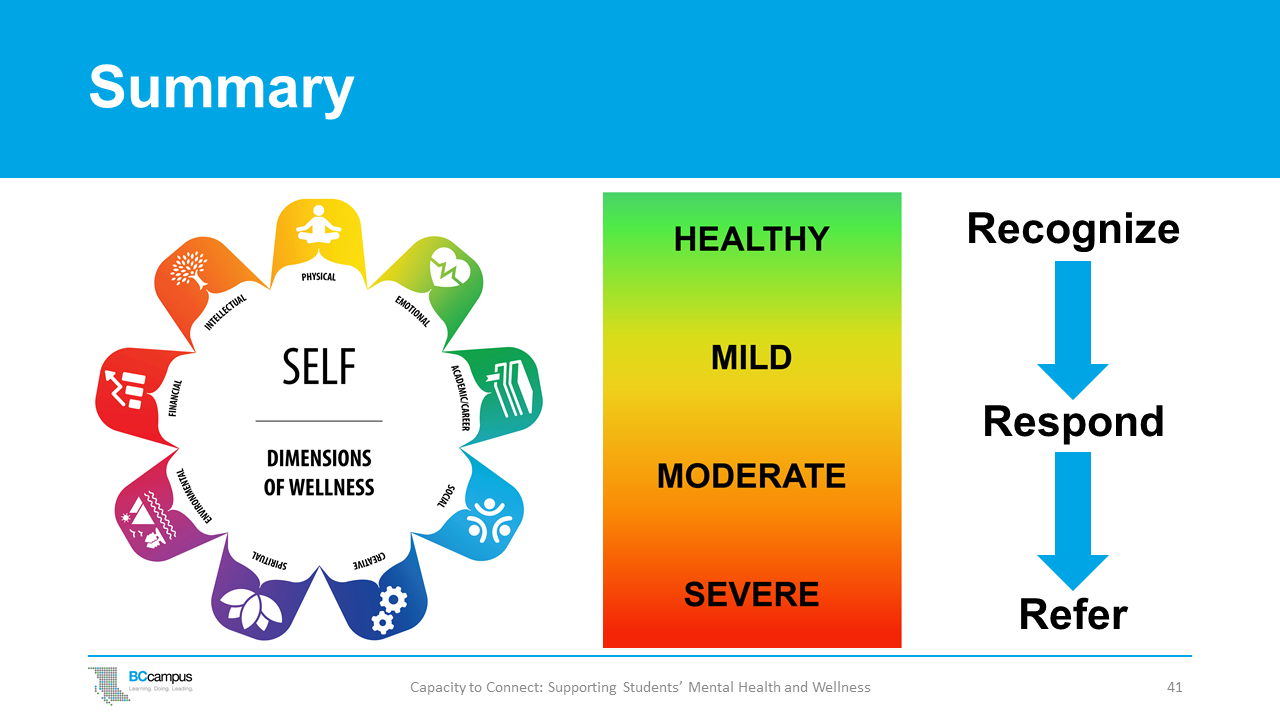

To close the session, review the Wellness Wheel, the Mental Health Continuum, and the Three Rs Framework.

Review everything you’ve talked about: how to recognize signs of distress in students, how to respond empathically while considering your own limits and a balance of care and respect, and how to refer to appropriate supports for you and for students.

If you haven’t already shared resources, hand out or share the links to any resource sheets available as well as campus and community resources and Handouts 1 and 2.

You might also like to read aloud the Maya Angelou quote to conclude the session.

“I’ve learned that people will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel.”

—Maya Angelou

Invite questions and comments.

1

Handout 1 is a two-page PDF of a Wellness Wheel worksheet for faculty and staff to share with students who are experiencing stress and feeling overwhelmed. It shows the Wellness Wheel and gives descriptions and examples of the nine dimension of wellness.

Download the Wellness Wheel Worksheet:

Physical wellness: Taking care of your body through physical activity, nutrition, sleep, and mental well-being. For example:

Emotional wellness: Making time to relax, reduce stress, and take care of yourself. Paying attention to both positive and negative feelings and understanding how to handle these emotions. For example:

Academic/career wellness: Expanding your knowledge and creating strategies to support continued learning. For example:

Social wellness: Taking care of your relationships and society by building healthy, nurturing, and supportive relationships and fostering a genuine connection with those around you. For example:

Creative wellness: Valuing and actively participating in arts and cultural experiences as a means to understand and appreciate the surrounding world. For example:

Spiritual wellness: Taking care of your values and beliefs and creating purpose in your life. For example:

Environmental wellness: Taking care of what is around you. Living in harmony with the Earth by taking action to protect it and respecting nature and all species. For example:

Financial wellness: Learning how to successfully manage finances to be financially responsible and independent. For example:

Intellectual wellness: Being open to exploring new concepts, gaining new skills, and seeking creative and stimulating activities. For example:

Wellness Wheel Handout. Adapted from Okanagan College. Wellness peer ambassador handbook. Kelowna, B.C.: Okanagan College.

2

Handout 2 is a resource to help faculty and staff recognize some signs and symptoms of students in distress. It provides tips on how to refer a student in distress for further assistance. It also include six scenarios of students in distress and suggested scripts for how to talk to these students and refer them to other services.

Download this handout:

Student life is a period of unique change filled with challenging events. As a member of the post-secondary community, you may identify and have the opportunity to support students who are struggling with issues that affect their mental health and well-being. This handout will help you recognize some signs and symptoms of students in distress. It provides tips on how to refer a student in distress for further assistance through Counselling Services or other appropriate resources.

A common indicator of distress is change – behaving or reacting in ways that are not typical for an individual.

“I noticed you were tearful in class today.”

“I noticed that your grades have dropped.”

“Is everything okay?”

Listen in non-judgmental fashion.

“Is there something I can do to help you?”

“It sounds like you’re feeling overwhelmed.”

“What you’re feeling is normal…other students are having similar experiences.”

Provide students with information on campus services:

If possible, walk the student to the support services if you have a serious concern.

“Would you like me to help you connect with resources on campus?”

“Would you like to call together and book an appointment?”

“Seeking help through Counselling Services is confidential.”

“Would you like me to walk with you to the support services?”

Accessing services is voluntary, unless the situation is urgent and the student is not safe on their own.

Is anyone at risk of immediate harm? If yes, call 911 and then Campus Security.

You will be able to assist many distressed students on your own by simply listening and referring them for further help. Some students will, however, need much more than you can offer. Below are some signs to look for that may suggest the assistance of a professional is warranted:

Your ability to respond to students who need help will be influenced by your personal style and the role you play at your institution. When helping students, it is important to remember to maintain your own boundaries. Recognize what you can and can’t do given the limitations of your role. Refer students as appropriate and access your own support when needed.

Staff of the various Student Services on campus can meet with staff and faculty who are concerned about a student and are unsure how to handle the situation. You are encouraged to consult when:

TRUST YOUR INSTINCTS and respond if a student situation leaves you feeling worried, alarmed, or threatened. If you are unsure, please consult. Once the student is supported, ensure that you are supported, while maintaining the confidentiality of the student. Talk to friends, family, Elders, colleagues.

The following six scenarios offer participants opportunities during the workshop to think about and practise responding to situations of students in distress. People may also want to read and reflect on them in their own time.

We encourage people to use these scenarios as starting points, not scripts, for discussions and continued thought about how we can respond with empathy to students while recognizing and honouring their strengths and capacity to achieve balance.

A student has just found out they failed an exam and starts to cry while talking to their instructor.

I can see that you are upset about the exam. I can hear the disappointment in your voice. You’ve said that you don’t feel that you can stay to attend the class, but I’m concerned about having you leave like this. I want to support you, but I have to teach this class right now. I wonder if you’d be willing to talk to a counsellor? It’s confidential. Would it help you to have someone from class or a friend walk over with you? Who will you ask? Let me call Counselling Services and tell them to expect you.

An Indigenous student comes into your office upset. They disclose to you that a close relative has just died unexpectedly, and they are stressed about how to ask their instructors for leave time from classes to go home for the ceremony and funeral. They explain to you that cultural protocols regarding the death of a family member are elaborate and can take up to a week or more to complete. They feel overwhelmed because they want to be home with their family and community, but they also have upcoming projects due in many of their courses. They express feelings of hopelessness during this interaction.

I am so sorry to hear about your loss; dealing with grief while trying to manage other responsibilities can be so challenging. I commend you for your resilience in such a difficult time; you are actively looking for support and that is important to honour in yourself.

Are there any cultural supports here that I can assist you in connecting with? Have you spoken with the staff in Indigenous Services? As for advocating for your needs with your instructors for leave time, I am happy to help you navigate that process – there are ways to make a request to your instructors for an extension on any class work or assignments. Shall we map out how you can email your instructors? Would you like me to connect you with Indigenous Services? I can introduce you to the staff there if you don’t already know them. I think they’ll be really receptive to supporting you in your request to the instructors as well and might have community or cultural supports that you can use.

An international student who is on probation has just failed an exam. The student fears they will be suspended and forced to go back to their home country, but they would be a disgrace to their family and they couldn’t face them. The student says that they can’t see any other option but to end it all.

I can see that you are upset about the exam. I can hear the disappointment in your voice and understand the fear about what will happen for you. When you say you might end it, I wonder if you mean you are thinking about suicide? I want to support you to be safe and to have a good outcome from this challenging time. I wonder if you’d be willing to talk to a counsellor? It’s confidential and I think it’s a wise thing to do. I’d like to walk over there with you.

If the student refuses, you could say, Another option is for us to call the crisis line together right now so you can talk with them and find out about some resources.

If the student says no, you could say, I care about you and am worried about you, so for me to feel comfortable, I need to have someone contact you to see how you’re doing and help support you.

A student presents as agitated and tearful. The student just found out they didn’t get a student loan. They talked to their parents, who are clear about not giving them money. They have paid their fees for courses but will not have enough money to get through the semester and are considered dropping out.

I’m sorry that you are having such a difficult time. I can see how upsetting this is to you and how much you want to take these classes. Have you spoken about your concerns with someone at the Financial Aid office? Are you aware of where they are located? Have you spoken to the chair of your department or to Academic Advising?

Do you have anyone to talk to about this? Perhaps you’d find it helpful to talk with someone in Counselling Services about making a plan for next steps. They are just down the hall. I can walk you there if you like. If you need support after hours you can also call the crisis line for support; here is their number.

A student who has disclosed to you in the past that they are transgender approaches you in tears. When you ask what is happening, they tell you that they were home with their family over the holiday break and they “came out” to their family. The family’s response was not supportive, and the student tells you their parents made hurtful and derogatory comments during the discussion. The student makes statements like “This is so difficult. I can’t keep going like this,” and “I don’t know why I even try anymore; my own parents don’t love me or accept me for who I am.” I am tired of having to validate myself and who I am.” They share other more general feelings of loneliness and hopelessness.

Thank you for sharing this with me, I can appreciate this is such a difficult time for you and this has a significant impact on your well-being. While I don’t personally know what it’s like to identify in the LGBTQ2S+ community and not have the support or acceptance of your family, I can appreciate that this is a fundamentally important aspect of your well-being. Do you have any ideas on how I might be able to support you through this?

Have you connected with our Pride Centre or Student Union office on campus? I am happy to walk you over there now if you would like.

I have heard you make some statements around feeling hopeless and losing a sense of purpose in your life generally. Are you having any thoughts of self-harm or suicide? We have counselling services on campus that are confidential and free for all students; can I walk you down to their office so you can meet them and see if it would be a good fit to talk with one of their team?

If the student says no, you could say: Another option is for us to call the crisis line together right now so you can talk with them and find out about some resources.

I want you to know that I support you; you are a valued and important member of our campus community. I would like to support you in any way that I can to know that you are seen, valued, and celebrated here on campus.

You noticed a student in class who has been wearing the same clothes on a few occasions and looks somewhat dishevelled. They appear tense at times and other times they’ve seemed sleepy in class. Last class you walked by them and wondered if you smelled alcohol. They have been handing in their assignments but doing mediocre, and their grades have been dropping. The most recent assignment wasn’t handed in. You feel concerned but not sure if all of these observations are enough reason to act.

Thank you for meeting with me. I’ve been feeling concerned about how you are doing. I can see that you are motivated to be here as your attendance has been good. At the beginning you seemed enthusiastic about the material and discussions. However you seem tense and tired. Your grades have been going down and your last assignment was late. Last class I wondered if I smelled alcohol. I wonder how you are doing and I’m concerned you are going through a challenging time that is interfering with your ability to do as well as you can at school.

I’m glad that we are talking, although I feel that it’s beyond my scope/role to talk to you in detail about what’s happening. I’ve found that in times of challenge it’s helpful to get support for myself. Seeking help is courageous, not weak, and shows you are committed to working through the hard times. Do you have someone you can talk to? Have you considered accessing Counselling Services to talk or find out about resources? It’s confidential.

There are other supports on campus, and I wonder if you are aware of them and if anything would be useful to you. The campus website lists all of the student resources in one place: I’m happy to show it to you. The crisis line is also good to know about as they can provide support and ideas of community resources.

3

Gemma Armstrong

Michelle Daoust

Ycha Gil

Faye Shedletzky

Albert Seinen

Jewell Gillies

Barbara Johnston

Liz Warwick

Brie Deimling, Royal Roads University

Amy Haagsma, West Coast Editorial Associates

Michelle Glubke, BCcampus

Lehoa Mak, Simon Fraser University

Brenda McKay, Vancouver Island University

Josephine McNeilly, Vancouver Island University

Kaitlyn Zheng, BCcampus

Okanagan College Student Services Division

Tara Black, Simon Fraser University

Andrei Bondoreff, Ministry of Advanced Education and Skills Training

Kelly Chirhart, Ministry of Advanced Education and Skills Training

Heidi Deagle, North Island College

Brie Deimling, Royal Roads University

Rafael de la Peña, College of New Caledonia

Brin Dunphy, College of New Caledonia

Kate Gates, Vancouver Community College

Eva Gavaris, Okanagan College

Michelle Glubke, BCcampus

Thierry Iradukunda, North Island College

Kate Jennings, Vancouver Island University

Nina Johnson, Thompson Rivers University

Melissa Lafrance, Simon Fraser University

Lehoa Mak, Simon Fraser University

Michael Mandrusiak, British Columbia Institute of Technology

Brenda McKay, Vancouver Island University

Shelley McKenzie, University of Northern British Columbia

Josephine McNeilly, Vancouver Island University

Karen Mason, North Island College

Laurie Michaud, North Island College

Declan Robinson Spence, BCcampus

Doris Silva, College of the Rockies

4