Visit Audio Recordings for the audio version of this section.

- Describe emotional intelligence.

- Describe personality types and tools used to describe them.

- Describe the relationship between leadership style and personality types.

- Describe people skills that are necessary for negotiation and conflict resolution.

- Describe how work is delegated.

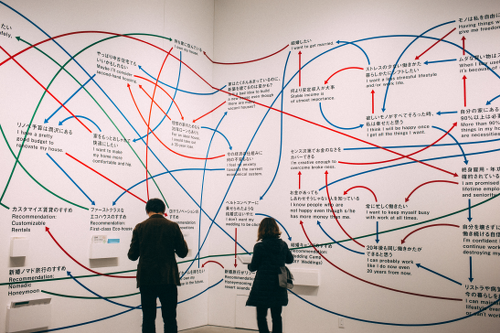

- Describe individual goals that are related to personality types.

Working with other people involves dealing with them both logically and emotionally. A successful working relationship between individuals begins with appreciating the importance of emotions and how they relate to personality types, leadership styles, negotiations, and setting goals.

Image by Christina Wocintechchat-com

Emotional Intelligence

Emotions are both a mental and physiological response to environmental and internal stimuli. Leaders need to understand and value their emotions to appropriately respond to the client, project team, and project environment. Daniel Coleman1 discussed emotional intelligence quotient (EQ) as a factor more important than IQ in predicting leadership success. According to Robert Cooper and Ayman Sawaf, “Emotional intelligence is the ability to sense, understand, and effectively apply the power and acumens of emotions as a source of human energy, information, connection, and influence.”2

Emotional intelligence includes the following:

- Self-awareness

- Self-regulation

- Empathy

- Relationship management

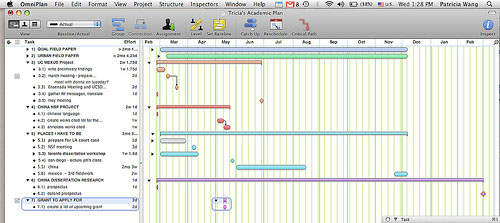

Image by Infusionsoft

Emotions are important to generating energy around a concept, to building commitment to goals, and to developing high-performing teams. Emotional intelligence is an important part of the project manager’s ability to build trust among the team members and with the client. It is an important factor in establishing credibility and an open dialogue with project stakeholders. Emotional intelligence is critical for project managers, and the more complex the project profile, the more important the project manager’s EQ becomes to project success.

Personality Types

Personality types refer to the differences among people in such matters as what motivates them, how they process information, how they handle conflict, etc. Understanding people’s personality types is acknowledged as an asset in interacting and communicating with them more effectively. Understanding your personality type as a project manager will assist you in evaluating your tendencies and strengths in different situations. Understanding others’ personality types can also help you coordinate the skills of your individual team members and address the various needs of your client.

The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) is one of the most widely used tools for exploring personal preference, with more than two million people taking the MBTI each year. The MBTI is often referred to as simply the Myers-Briggs. It is a tool that can be used in project management training to develop an awareness of preferences for processing information and relationships with other people.

Based on the theories of psychologist Carl Jung, the Myers-Briggs uses a questionnaire to gather information on the ways individuals prefer to use their perception and judgment. Perception represents the way people become aware of people and their environment. Judgment represents the evaluation of what is perceived. People perceive things differently and reach different conclusions based on the same environmental input. Understanding and accounting for these differences is critical to successful project leadership.

The Myers-Briggs identifies sixteen personality types based on four preferences derived from the questionnaire. The preferences are between pairs of opposite characteristics and include the following:

- Extroversion (E)-Introversion (I)

- Sensing (S)-Intuition (N)

- Thinking (T)-Feeling (F)

- Judging (J)-Perceiving (P)

Sixteen Myers-Briggs types can be derived from the four dichotomies. Each of the sixteen types describes a preference: for focusing on the inner or outer world (E-I), for approaching and internalizing information (S-I), for making decisions (T-F), and for planning (J-P). For example, an ISTJ is a Myers-Briggs type who prefers to focus on the inner world and basic information, prefers logic, and likes to decide quickly.

It is important to note that there is no best type and that effective interpretation of the Myers-Briggs requires training. The purpose of the Myers-Briggs is to understand and appreciate the differences among people. This understanding can be helpful in building the project team, in developing common goals, and communicating with project stakeholders. For example, different people process information differently. Extraverts prefer face-to-face meetings as the primary means of communicating, while introverts prefer written communication. Sensing types focus on facts, and intuitive types want the big picture.

On larger, more complex projects, some project managers will use the Myers-Briggs as a team-building tool during project start-up. This is typically a facilitated work session where team members take the Myers-Briggs and share with the team how they process information, what communication approaches they prefer, and what decision-making preferences they have. This allows the team to identify potential areas of conflict, develop communication strategies, and build an appreciation for the diversity of the team.

It should be taken into consideration that the MBTI has encountered significant academic criticism related to its validity and reliability. Research by Pittenger illustrates that there is insufficient data to support the MBTI’s claim that there is a total of 16 unique types of personality and further suggests that “there is no convincing evidence to justify that knowledge of type is a reliable or valid predictor of important behavioural conditions.”3 While the MBTI may be beneficial in understanding stereotypical personality traits, it falls short of capturing a person’s full individuality.4

Another theory of personality typing is the DISC method, which rates people’s personalities by testing a person’s preferences in word associations in the following four areas:

- Dominance/Drive—relates to control, power, and assertiveness

- Inducement/Influence—relates to social situations and communication

- Submission/Steadiness—relates to patience, persistence, and thoughtfulness

- Compliance/Conscientiousness—relates to structure and organization

One project team in South Carolina used colour-coded badges for the first few weeks of the project to indicate Myers-Briggs type. For this team, this was a way to explore how different team members processed information, made decisions, and took action.

Understanding the differences among people is a critical leadership skill. This includes understanding how people process information, how different experiences will influence the way people perceive the environment, and how people develop filters that allow certain information to be incorporated while other information is excluded. The more complex the project, the more important the understanding of how people process information, make decisions, and deal with conflict. There are multiple personality-type tests that have been developed and explore different aspects of people’s personalities. It might be prudent to explore the different tests available and utilize the one(s) that are most beneficial for your team.

Leadership Styles

Leadership style is a function of both the personal characteristics of the leader and the environment in which the leadership must occur, and a topic which several researchers have attempted to understand. Robert Tannenbaum and Warren Schmidt5 described leaders as either autocratic or democratic. Harold Leavitt6 described leaders as pathfinders (visionaries), problem solvers (analytical), or implementers (team oriented). James MacGregor Burns7 conceived leaders as either transactional (focused on actions and decisions) or transformational (focused on the long-term needs of the group and organization).

Fred Fiedler8 introduced his contingency theory, which is the ability of leaders to adapt their leadership approach to the environment. Most leaders have a dominant leadership style that is most comfortable for them. For example, most engineers spend years training in analytical problem solving and often develop an analytical approach to leadership.

A leadership style reflects personal characteristics and life experiences. Although a project manager’s leadership style may be predominantly a pathfinder (using Leavitt’s taxonomy), most project managers become problem solvers or implementers when they perceive the need for these leadership approaches. The leadership approach incorporates the dominant leadership style and Fiedler’s contingency focus on adapting to the project environment.

No particular leadership approach is specifically appropriate for managing a project. Due to the unique circumstances inherent in each project, the leadership approach and the management skills required to be successful vary depending on the complexity profile of the project. However, the Project Management Institute published research that studied project management leadership traits9 and concluded that good communication skills and the ability to build harmonious relationships and motivate others are essential. Beyond this broad set of leadership skills, the successful leadership approach will depend on the profile of the project. For example, a transactional project manager with a strong command-and-control leadership approach may be very successful on a small software development project or a construction project, where tasks are clear, roles are well understood, and the project environment is cohesive. This same project manager is less likely to be successful on a larger, more complex project with a diverse project team and complicated work processes.

Matching the appropriate leadership style and approach to the complexity profile of the project is a critical element of project success. Even experienced project managers are less likely to be successful if their leadership approach does not match the complexity profile of the project.

Each project phase may also require a different leadership approach. During the start-up phase of a project, when new team members are first assigned to the project, the project may require a command-and-control leadership approach. Later, as the project moves into the conceptual phase, creativity becomes important, and the project management takes on a more transformational type leadership approach. Most experienced project managers are able to adjust their leadership approach to the needs of the project phase. Occasionally, on very large and complex projects some companies will bring in different project managers for various phases of a project. Changing project managers may bring the right level of experience and the appropriate leadership approach, but is also disruptive to a project. Senior management must balance the benefit of matching the right leadership approach with the cost of disrupting established relationships.

On a project to publish a new textbook at a major publisher, a project manager led a team that included members from partners that were included in a joint venture. The editorial manager was Greek, the business manager was German, and other members of the team were from various locations in the United States and Europe. In addition to the traditional potential for conflict that arises from team members from different cultures, the editorial manager and business manager were responsible for protecting the interest of their company in the joint venture.

The project manager held two alignment or team-building meetings. The first was a two-day meeting held at a local resort and included only the members of the project leadership team. An outside facilitator was hired to facilitate discussion, and the topic of cultural conflict and organizational goal conflict quickly emerged. The team discussed several methods for developing understanding and addressing conflicts that would increase the likelihood of finding mutual agreement.

The second team-building session was a one-day meeting that included the executive sponsors from the various partners in the joint venture. With the project team aligned, the project manager was able to develop support for the publication project’s strategy and commitment from the executives of the joint venture. In addition to building processes that would enable the team to address difficult cultural differences, the project manager focused on building trust with each of the team members. The project manager knew that building trust with the team was as critical to the success of the project as the technical project management skills and devoted significant management time to building and maintaining this trust.

Leadership Skills

Einsiedel10 discussed the qualities of successful project managers. The project manager must be perceived to be credible by the project team and key stakeholders. The project manager can solve problems. A successful project manager has a high degree of tolerance for ambiguity. On projects, the environment changes frequently, and the project manager must apply the appropriate leadership approach for each situation.

A successful project manager must have good communication skills. Barry Posner11 connected project management skills to solving problems. All project problems were connected to skills needed by the project manager:

- Breakdown in communication represented the lack of communication skills.

- Uncommitted team members represented the lack of team-building skills.

- Role confusion represented the lack of organizational skills.

The research indicates that project managers need a large number of skills. These skills include administrative skills, organizational skills, and technical skills associated with the technology of the project. The types of skills and the depth of the skills needed are closely connected to the complexity profile of the project. Typically on smaller, less complex projects, project managers need a greater degree of technical skills. On larger, more complex projects, project managers need more organizational skills to deal with the complexity. On smaller projects, the project manager is intimately involved in developing the project schedule, cost estimates, and quality standards. On larger projects, functional managers are typically responsible for managing these aspects of the project, and the project manager provides the organizational framework for the work to be successful.

Listening

One of the most important communication skills of the project manager is the ability to actively listen. Active listening is placing oneself in the speaker’s position as much as possible, understanding the communication from the point of view of the speaker, listening to the body language and other environmental cues, and striving not just to hear, but to understand. Active listening takes focus and practice to become effective. Active listening enables a project manager to go beyond the basic information that is being shared and to develop a more complete understanding of the information.

A client just returned from a trip to Australia where he reviewed the progress of the project with his company’s board of directors. The project manager listened and took notes on the five concerns expressed by the board of directors to the client.

The project manager observed that the client’s body language showed more tension than usual. This was a cue to listen very carefully. The project manager nodded occasionally and clearly demonstrated he was listening through his posture, small agreeable sounds, and body language. The project manager then began to provide feedback on what was said using phrases like “What I hear you say is…” or “It sounds like.…” The project manager was clarifying the message that was communicated by the client.

The project manager then asked more probing questions and reflected on what was said. “It sounds as if it was a very tough board meeting.” “Is there something going on beyond the events of the project?” From these observations and questions, the project manager discovered that the board of directors meeting did not go well. The company had experienced losses on other projects, and budget cuts meant fewer resources for the project and an expectation that the project would finish earlier than planned. The project manager also discovered that the client’s future with the company would depend on the success of the project. The project manager asked, “Do you think we will need to do things differently?” They began to develop a plan to address the board of directors’ concerns.

Through active listening, the project manager was able to develop an understanding of the issues that emerged from the board meeting and participate in developing solutions. Active listening and the trusting environment established by the project manager enabled the client to safely share information he had not planned on sharing and to participate in creating a workable plan that resulted in a successful project.

In the example above, the project manager used the following techniques:

- Listening intently to the words of the client and observing the client’s body language

- Nodding and expressing interest in the client without forming rebuttals

- Providing feedback and asking for clarity while repeating a summary of the information back to the client

- Expressing understanding and empathy for the client.

Active listening was important in establishing a common understanding from which an effective project plan could be developed.

Negotiation

When multiple people are involved in an endeavour, differences in opinions and desired outcomes naturally occur. Negotiation is a process for developing a mutually acceptable outcome when the desired outcome for each party conflicts. A project manager will often negotiate with a client, with team members, with vendors, and with other project stakeholders. Negotiation is an important skill in developing support for the project and preventing frustration among all parties involved, which could delay or cause project failure.

Vijay Verma12 suggests that negotiations involve four principles:

- Separate people from the problem. Framing the discussions in terms of desired outcomes enables the negotiations to focus on finding new outcomes.

- Focus on common interests. By avoiding the focus on differences, both parties are more open to finding solutions that are acceptable.

- Generate options that advance shared interests. Once the common interests are understood, solutions that do not match with either party’s interests can be discarded, and solutions that may serve both parties’ interests can be more deeply explored.

- Develop results based on standard criteria. The standard criterion is the success of the project. This implies that the parties develop a common definition of project success.

For the project manager to successfully negotiate issues on the project, he or she should first seek to understand the position of the other party. If negotiating with a client, what is the concern or desired outcome of the client? What are the business drivers and personal drivers that are important to the client? Without this understanding, it is difficult to find a solution that will satisfy the client. The project manager should also seek to understand what outcomes are desirable to the project. Typically, more than one outcome is acceptable. Without knowing what outcomes are acceptable, it is difficult to find a solution that will produce that outcome.

One of the most common issues in formal negotiations is finding a mutually acceptable price for a service or product. Understanding the market value for a product or service will provide a range for developing a negotiation strategy. The price paid on the last project or similar projects provides information on the market value. Seeking expert opinions from sources who would know the market is another source of information. Based on this information, the project manager can then develop an expected range from the lowest price that would be expected within the current market to the highest price.

Additional factors will also affect the negotiated price. The project manager may be willing to pay a higher price to assure an expedited delivery or a lower price if the delivery can be made at the convenience of the supplier or if payment is made before the product is delivered. Developing as many options as possible provides a broader range of choices and increases the possibility of developing a mutually beneficial outcome.

The goal of negotiations is not to achieve the lowest costs, although that is a major consideration, but to achieve the greatest value for the project. If the supplier believes that the negotiation process is fair and the price is fair, the project is more likely to receive higher value from the supplier. The relationship with the supplier can be greatly influenced by the negotiation process and a project manager that attempts to drive the price unreasonably low or below the market value will create an element of distrust in the relationship that may have negative consequences for the project. A positive negotiation experience may create a positive relationship that may be beneficial, especially if the project begins to fall behind schedule and the supplier is in a position to help keep the project on schedule.

Negotiation on a Textbook Adoption Project

After difficult negotiations on an open textbook adoption project in Indiana, the project management team met with the publisher and asked, “Now that the negotiations are complete, how can we help you get more adoptions?” Although this question surprised the publisher, the team had discussed how information would flow, and confusion in expectations and unexpected changes always cost the supplier more money. The team developed mechanisms for assuring good information and providing early information on possible changes and tracked the effect of these efforts during the life of the project.

These efforts and the increased trust enabled the publisher to increase adoptions on the project, and the publisher made special efforts to meet every project expectation. During the life of the project, the publisher shared several ideas about how to reduce total project costs and increase efficiencies. The positive outcome was the product of good partner management by the project team, but the relationship could not have been successful without good faith negotiations.

Conflict Resolution

Conflict on a project is to be expected because of the level of stress, the lack of information during the early phases of the project, personal differences, role conflicts, and limited resources. Although good planning, communication, and team building can reduce the amount of conflict, conflict will still emerge. How the project manager deals with the conflict results in the conflict being destructive or an opportunity to build energy, creativity, and innovation.

David Whetton and Kim Cameron13 developed a response-to-conflict model that reflected the importance of the issue balanced against the importance of the relationship. The model presented five responses to conflict:

- Avoiding

- Forcing

- Collaborating

- Compromising

- Accommodating

Each of these approaches can be effective and useful depending on the situation. Project managers will use each of these conflict resolution approaches depending on the project manager’s personal approach and an assessment of the situation.

Most project managers have a default approach that has emerged over time and is comfortable. For example, some project managers find the use of the project manager’s power the easiest and quickest way to resolve problems. “Do it because I said to” is the mantra for project managers who use forcing as the default approach to resolve conflict. Some project managers find accommodating with the client the most effective approach to dealing with client conflict.

The effectiveness of a conflict resolution approach will often depend on the situation. The forcing approach often succeeds in a situation where a quick resolution is needed, and the investment in the decision by the parties involved is low.

Two senior managers both want the office with the window. The project manager intercedes with little discussion and assigns the window office to the manager with the most seniority. The situation was a low-level conflict with no long-range consequences for the project and a solution all parties could accept.

Sometimes office size and location is culturally important, and this situation would take more investment to resolve.

In another example, the client rejected a request for a change order because she thought the change should have been foreseen by the project team and incorporated into the original scope of work. The project controls manager believed the client was using her power to avoid an expensive change order and suggested the project team refuse to do the work without a change order from the client.

This is a more complex situation, with personal commitments to each side of the conflict and consequences for the project. The project manager needs a conflict resolution approach that increases the likelihood of a mutually acceptable solution for the project. One conflict resolution approach involves evaluating the situation, developing a common understanding of the problem, developing alternative solutions, and mutually selecting a solution. Evaluating the situation typically includes gathering data. In our example of a change order conflict, gathering data would include a review of the original scope of work and possibly of people’s understandings, which might go beyond the written scope. The second step in developing a resolution to the conflict is to restate, paraphrase, and reframe the problem behind the conflict to develop a common understanding of the problem. In our example, the common understanding may explore the change management process and determine that the current change management process may not achieve the client’s goal of minimizing project changes. This phase is often the most difficult and may take an investment of time and energy to develop a common understanding of the problem.

After the problem has been restated and agreed on, alternative approaches are developed. This is a creative process that often means developing a new approach or changing the project plan. The result is a resolution to the conflict that is mutually agreeable to all team members. If all team members believe every effort was made to find a solution that achieved the project charter and met as many of the team member’s goals as possible, there will be a greater commitment to the agreed-on solution.

In our example, the project team found a new way to accomplish the project goals without a change to the project scope. On this project, the solution seemed obvious after some creative discussions, but in most conflict situations, even the most obvious solutions can be elusive.

Delegation

Delegating responsibility and work to others is a critical project management skill. The responsibility for executing the project belongs to the project manager. Often other team members on the project will have a functional responsibility on the project and report to a functional manager in the parent organization. For example, the procurement leader for a major project may also report to the organization’s vice president for procurement. Although the procurement plan for the project must meet the organization’s procurement policies, the procurement leader on the project will take day-to-day direction from the project manager. The amount of direction given to the procurement leader, or others on the project, is the decision of the project manager.

If the project manager delegates too little authority to others to make decisions and take action, the lack of a timely decision or lack of action will cause delays on the project. Delegating too much authority to others who do not have the knowledge, skills, or information will typically cause problems that result in delay or increased cost to the project. Finding the right balance of delegation is a critical project management skill.

When developing the project team, the project manager selects team members with the knowledge, skills, and abilities to accomplish the work required for the project to be successful. Typically, the more knowledge, skills, abilities, and experience a project team member brings to the project, the more that team member will be paid. To keep the project personnel costs lower, the project manager will develop a project team with the level of experience and the knowledge, skills, and abilities to accomplish the work.

On smaller, less complex projects, the project manager can provide daily guidance to project team members and be consulted on all major decisions. On larger, more complex projects, there are too many important decisions made every day for the project manager to be involved at the same level, and project team leaders are delegated decision-making authority. Larger projects, with a more complex profile, will typically pay more because of the need for the knowledge and experience. On larger, more complex projects, the project manager will develop a more experienced and knowledgeable team that will enable the project manager to delegate more responsibility to these team members.

The project manager must have the skills to evaluate the knowledge, skills, and abilities of project team members and evaluate the complexity and difficulty of the project assignment. Often project managers want project team members they have worked with in the past. Because the project manager knows the skill level of the team member, project assignments can be made quickly with less supervision than with a new team member with whom the project manager has little or no experience.

Delegation is the art of creating a project organizational structure with the work organized into units that can be managed. Delegation is the process of understanding the knowledge, skills, and abilities needed to manage that work and then matching the team members with the right skills to do that work. Good project managers are good delegators.

Adjusting Leadership Styles

In the realm of personality traits, remember that they reflect an individual’s preferences, not their limitations. It is important to understand that each individual can still function in situations for which they are not best suited. It is also important to realize that you can change your leadership style according to the needs of your team and the particular project’s attributes and scope.

For example, a project leader who is more Thinking (T) than Feeling (F) (according to the Myers-Briggs model) would need to work harder to be considerate of how a team member who is more Feeling (F) might react if they were singled out in a meeting because they were behind schedule. If a person knows their preferences and which personality types are most successful in each type of project or project phase, they can set goals for improvement in their ability to perform in those areas that are not their natural preference.

Another individual goal is to examine which conflict resolution styles are least comfortable and work to improve those styles so that they can be used when they are more appropriate than your default style.

- Emotional intelligence is the ability to sense, understand, and effectively apply emotions.

- Two common tools for describing personality types are DISC (Dominance, Influence, Steadiness, and Conscientiousness) and the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI). The MBTI is the most common. It rates personalities on the position between extremes of four paired terms: Extroversion (E)-Introversion (I), Sensing (S)-Intuition (I), Thinking (T)-Feeling (F), and Judging (J)-Perceiving (P).

- Leadership styles are usually related to the personality of the leader. The type of leadership style that is most effective depends on the complexity and the phase of the project.

- Negotiation and conflict resolution require skill at listening and an understanding of emotional intelligence and personality types.

- Delegation is the art of creating a project organizational structure that can be managed and then matching the team members with the right skills to do that work.

- Individual goals can be set for improving abilities that are not natural personality strengths to deal with projects and project phases.

[1] Daniel Goleman, Emotional Intelligence (New York: Bantam Books, 1995).

[2] Robert K. Cooper and Ayman Sawaf, Executive EQ, Emotional Intelligence in Leadership and Organizations (New York: Perigree Book, 1997), xiii.

[3] David G. Myers, Psychology 10th edition (Worth Publishers, 2013).

[4] David J. Pittenger, “The Utility of the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator,”. Review of Educational Research 63, no. 4 (1993): 467-488.

[5] Robert Tannenbaum and Warren Schmidt, “How to Choose a Leadership Pattern,” Harvard Business Review 36 (1958): 95–101.

[6] Harold Leavitt, Corporate Pathfinders (New York: Dow-Jones-Irwin and Penguin Books, 1986).

[7] James MacGregor Burns, Leadership (New York: Harper & Row, 1978).

[8] Fred E. Fiedler, “Validation and Extension of the Contingency Model of Leadership Effectiveness,” Psychological Bulletin 76, no. 2 (1971): 128–48.

[9] Qian Shi and Jianguo Chen, The Human Side of Project Management: Leadership Skills (Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute, Inc., 2006), 4–11.

[10] Albert A. Einsiedel, “Profile of Effective Project Managers,” Project Management Journal 18 (1987): 5.

[11] Barry Z. Posner, “What It Takes to Be a Good Project Manager,” Project Management Journal 18 (1987): 32–46.

[12] Vijay K. Verma, Human Resource Skills for the Project Manager (Sylvia, NC: PMI Publications, 1996), 145–75.

[13] David Whetton and Kim Cameron, Developing Management Skills (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, 2005).

New cover design, updated fonts, and enhanced list of Glossary terms.

New cover design, updated fonts, and enhanced list of Glossary terms.