- 8 Ps of services marketing

Refers to product, place, promotion, pricing, people, programming, partnership, and physical evidence.

- Adventure tourism

Outdoor activities with an element of risk, usually somewhat physically challenging and undertaken in natural, undeveloped areas.

- adventure tourism

Outdoor activities with an element of risk, usually somewhat physically challenging and undertaken in natural, undeveloped areas.

- Advertorial

Print content (sometimes appearing online) that is a combination of an editorial feature and paid advertising.

- advertorial

Print content (sometimes appearing online) that is a combination of an editorial feature and paid advertising.

- Agritourism

Tourism experiences that highlight rural destinations and prominently feature agricultural operations

- agritourism

Tourism experiences that highlight rural destinations and prominently feature agricultural operations

- Ancillary revenues

Money earned on non-essential components of the transportation experience including headsets, blankets, and meals.

- ancillary revenues

Money earned on non-essential components of the transportation experience including headsets, blankets, and meals.

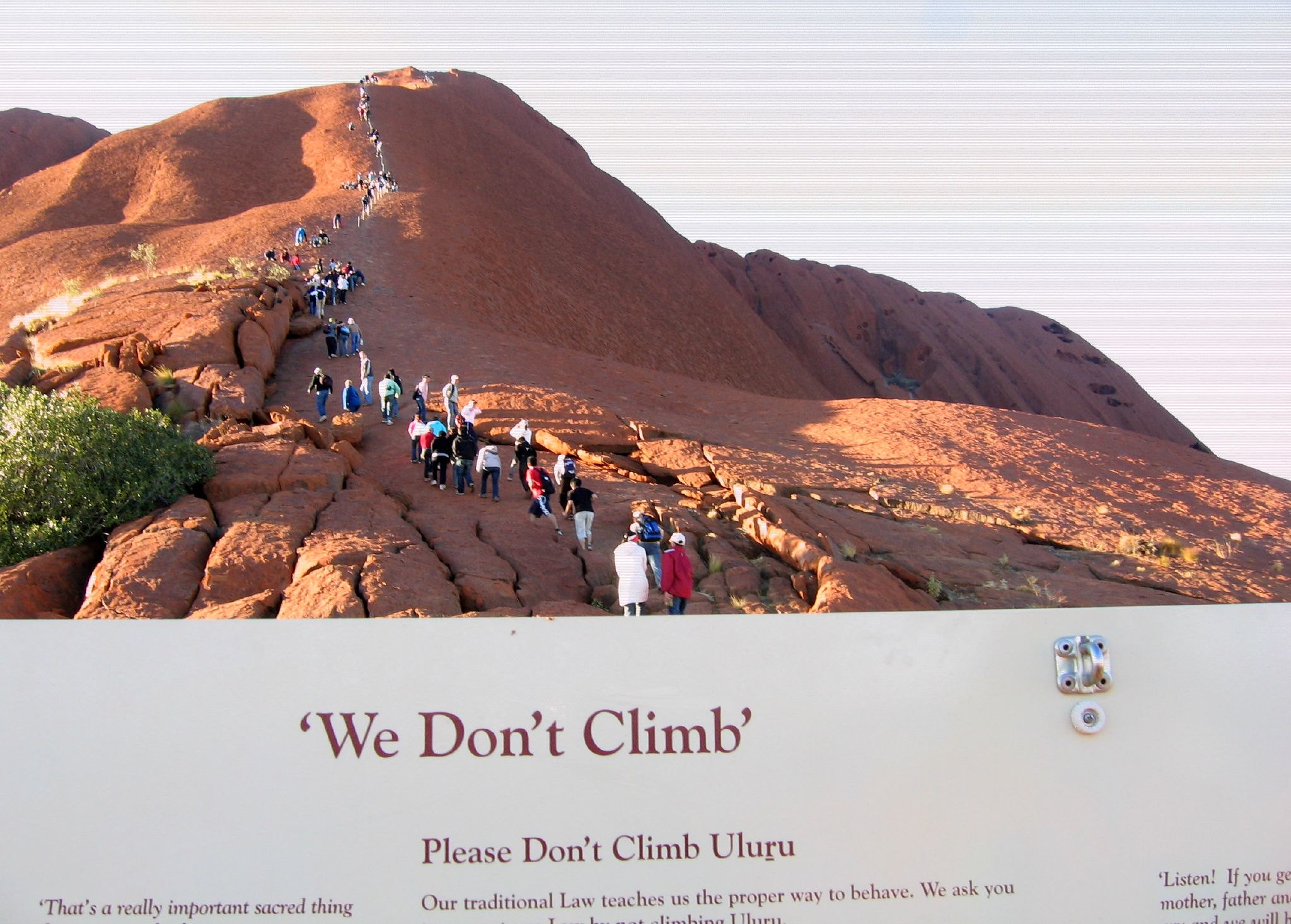

- Appropriation

The action of taking something for one's own use, typically without the owner's permission.

- appropriation

The action of taking something for one's own use, typically without the owner's permission.

- Art museum

Museums that collect historical and modern works of art for the educational purposes and to preserve them for future generations.

- art museum

Museums that collect historical and modern works of art for the educational purposes and to preserve them for future generations.

- Art museums

Museums that collect historical and modern works of art for educational purposes and to preserve them for future generations.

- Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC)

A forum that brings together countries from the Asia Pacific region (including Canada), and which has a Tourism Working Group that looks at policy development in a tourism context.

- Assets

Items of value owned by a business to be used in the production and service of the experience.

- assets

Items of value owned by a business to be used in the production and service of the experience.

- Association of Canadian Mountain Guides (ACMG)

Canada's only internationally recognized guiding association, offering a range of certifications.

- Association of Canadian Travel Agencies (ACTA)

A trade organization established in 1977 to ensure high standards of customer service, engage in advocacy for the trade, conduct research, and facilitate travel agent training.

- Authentic Indigenous Artisan Program

Protects Indigenous artists by identifying three tiers of artwork based on the degree to which Indigenous people have participated in their creation; a tool to combat cultural appropriation.

- Authenticity of experience

A hot topic in tourism that started with MacCannell in 1976 and continues to today; discussion of the extent to which experiences are staged for visitors.

- authenticity of experience

A hot topic in tourism that started with MacCannell in 1976 and continues to today; discussion of the extent to which experiences are staged for visitors.

- Avalanche Canada

A not-for-profit society that provides public avalanche forecasts and education for back country travellers venturing into avalanche terrain, dedicated to a vision of eliminating avalanche injuries and fatalities in Canada.

- Average cheque

Total sales divided by number of guests served.

- average cheque

Total sales divided by number of guests served.

- Average daily rate (ADR)

Average guest room income per occupied room in a given time period.

- average daily rate (ADR)

Average guest room income per occupied room in a given time period.

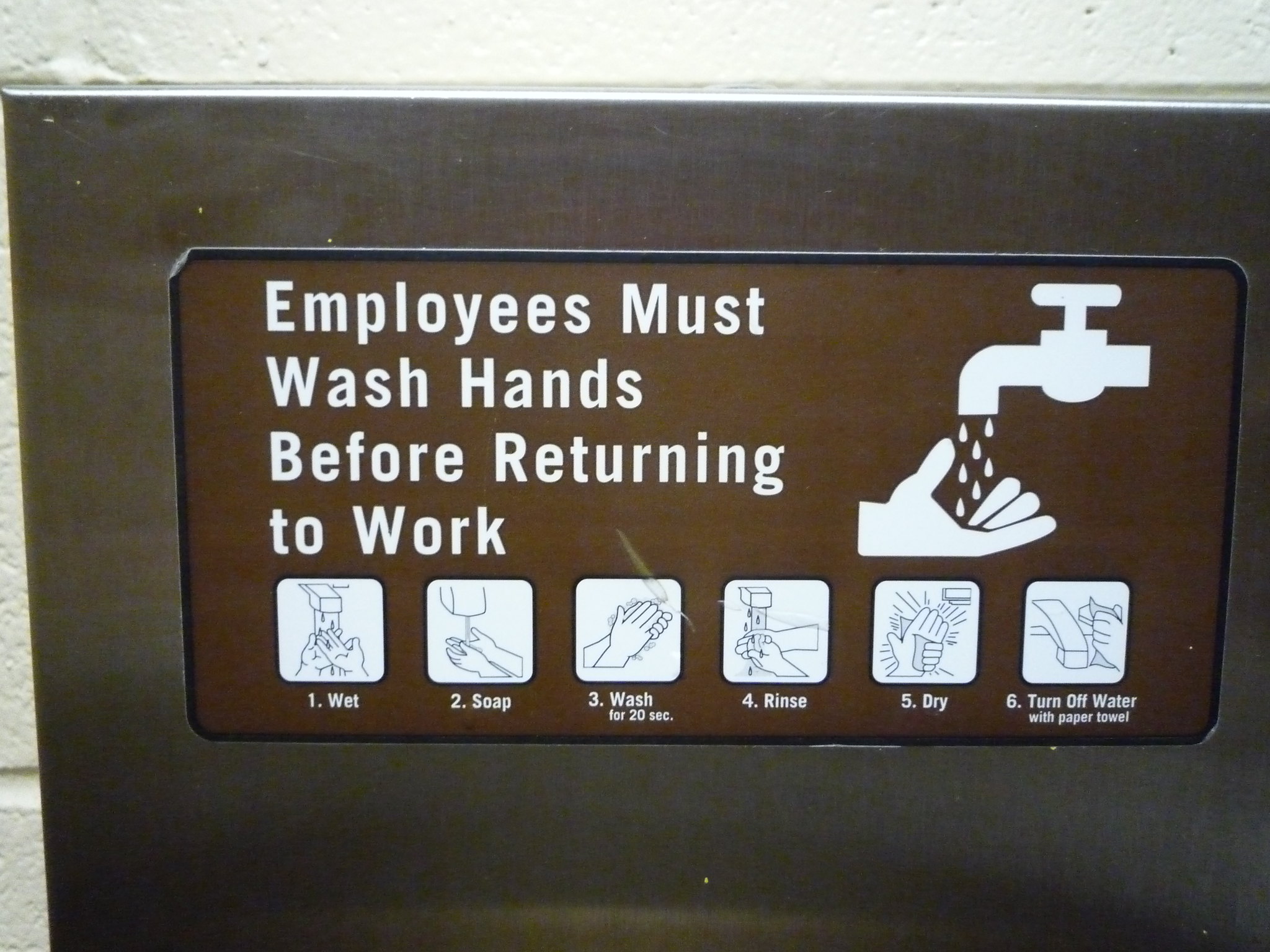

- Back of house

Food production areas not accessible to guests and not generally visible; also known as heart of house

- back of house

Food production areas not accessible to guests and not generally visible; also known as heart of house

- BC Hospitality Foundation (BCHF)

Created to help support hospitality professionals in their time of need; now also a provider of scholarships for students in hospitality management and culinary programs.

- BC Hotel Association (BCHA)

The trade association for BC's hotel industry, which hosts an annual industry trade show and seminar series, and publishes InnFocus magazine for professionals.

- BC Lodging and Campgrounds Association (BCLCA)

Represents the interests of independently owned campgrounds and lodges in BC.

- BC Parks

The agency responsible for management of provincial parks in British Columbia.

- BC Restaurant & Foodservices Association (BCRFA)

Representing the interests of more than 3000 of the province's foodservice operators in matters including wages, benefits, and liquor licenses, and other relevant matters.

- Beverage costs

Beverages sold in liquor-licensed operations; this usually only includes alcohol, but in unlicensed operations, it includes coffee, tea milk, juices, and soft drinks.

- beverage costs

Beverages sold in liquor-licensed operations; this usually only includes alcohol, but in unlicensed operations, it includes coffee, tea milk, juices, and soft drinks.

- Blue Sky Policy

Canada’s approach to open skies agreements that govern which countries’ airlines are allowed to fly to, and from, Canadian destinations.

- Botanical garden

A garden that displays native and/or non-native plants and trees, often running educational programming.

- botanical garden

A garden that displays native and/or non-native plants and trees, often running educational programming.

- Breach in the standard of care

Failure of a defendant to work to the recognized standard.

- breach in the standard of care

Failure of a defendant to work to the recognized standard.

- BRIC

An acronym for the growing economies of Brazil, Russia, India, and China.

- BRICS

The acronym for the BRIC countries with the addition of South Africa.

- British Columbia Golf Marketing Alliance

A strategic alliance representing 58 regional and destination golf resorts in BC with the goal of having BC achieve recognition nationally and internationally as a leading golf destination.

- British Columbia Government Travel Bureau (BCGTB)

The first recognized provincial government organization responsible for the tourism marketing of British Columbia.

- British Columbia Guest Ranchers Association (BCGRA)

An organization offering marketing opportunities and development support for BC's guest ranch operators.

- British Columbia Lottery Corporation (BCLC)

The crown corporation responsible for operating casinos, lotteries, bingo halls, and online gaming in the province of BC.

- British Columbia Snowmobile Federation (BCSF)

An organization offering snowmobile patrol services, lessons on operations, and advocating for the maintenance of riding areas in BC.

- Business Events Industry Coalition of Canada (BEICC)

An advocacy group for the meetings and events industry in Canada.

- Camping and RVing British Columbia Coalition (CRVBCC)

Represents campground managers and brings together additional stakeholders including the Recreation Vehicle Dealers Association of BC and the Freshwater Fisheries Society.

- Canada West Ski Areas Association (CWSAA)

Founded in 1966 and headquartered in Kelowna, BC, CWSAA represents ski areas and industry suppliers and provides government and media relations as well as safety and risk management expertise to its membership.

- Canada’s West Marketplace

A partnership between Destination BC and Travel Alberta, showcasing BC travel products in a business-to-business sales environment.

- Canada’s West Marketplace

A partnership between Destination BC and Travel Alberta, showcasing BC travel products in a business-to-business sales environment.

- Canadian Association of Tour Operators (CATO)

A membership-based organization that serves as the voice of the tour operator segment and engages in professional development and networking in the sector.

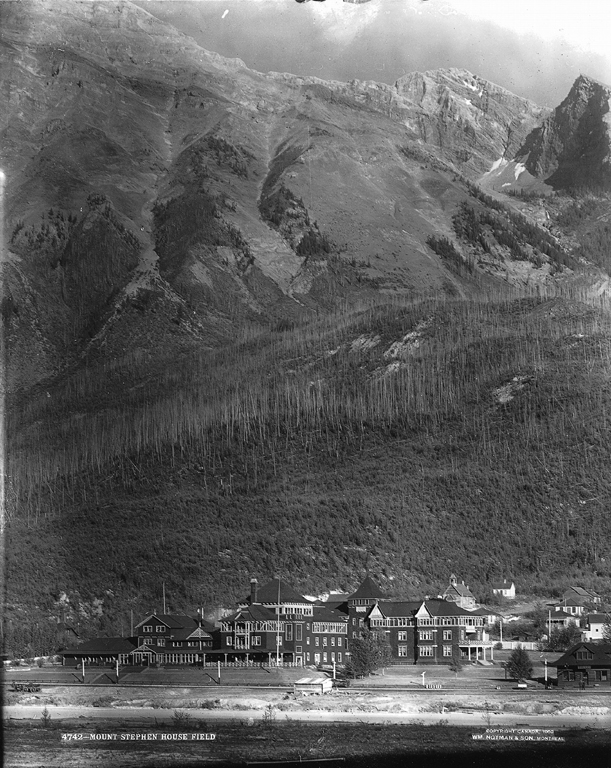

- Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR)

A national railway company widely regarded as establishing tourism in Canada and BC in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

- Canadian Ski Guide Association (CSGA)

Founded in British Columbia, an organization that runs a training institute for professional guides, and a separate non-profit organization representing CSGA guide and operating members.

- Canadian Sport Tourism Alliance (CSTA)

Created in 2000, an industry organization funded by the CTC, now Destination Canada, to increase Canadian capacity to attract and host sport tourism events.

- Canadian Tourism Commission (CTC)

The previous (old) name for Destination Canada.

- Capacity

The ability of a person to enter into a legal agreement; depends on the age and mental state of the person (among other factors).

- capacity

The ability of a person to enter into a legal agreement; depends on the age and mental state of the person (among other factors).

- Captured patrons

Consumers with limited selection or choice of food or beverage provider given their occupation or location.

- captured patrons

Consumers with limited selection or choice of food or beverage provider given their occupation or location.

- carbon offsetting

A market-based system that provides options for organizations to invest in green initiatives to offset their own carbon emissions.

- Carbon offsetting

A market-based system that provides options for organizations to invest in green initiatives to offset their own carbon emissions.

- Career planning

A series of deliberate steps with outcomes to help individuals achieve their short- and long-term career goals.

- career planning

A series of deliberate steps with outcomes to help individuals achieve their short- and long-term career goals.

- Carrying capacity

The maximum number of a given species that can be sustained in a specific habitat or biosphere without negative impacts.

- carrying capacity

The maximum number of a given species that can be sustained in a specific habitat or biosphere without negative impacts.

- Causation

A strong link between the actions of the defendant and the injury to the plaintiff.

- causation

A strong link between the actions of the defendant and the injury to the plaintiff.

- co-op education

A special program offered by a college/university in which students alternate work and study, usually spending a number of weeks in full-time study and a number in full-time employment away from the campus.

- Co-op education

A special program offered by a college/university in which students alternate work and study, usually spending a number of weeks in full-time study and a number in full-time employment away from the campus.

- Collaborative consumption

Also known as the sharing economy, a blend of economy, technology, and social movement where access to goods and skills is more important than ownership (e.g., Airbnb).

- collaborative consumption

Also known as the sharing economy, a blend of economy, technology, and social movement where access to goods and skills is more important than ownership (e.g., Airbnb).

- Commercial Bear Viewing Association of BC (CBVA)

Promoters of best practices in sustainable viewing, training, and certification for guides, and advocating for land use practices.

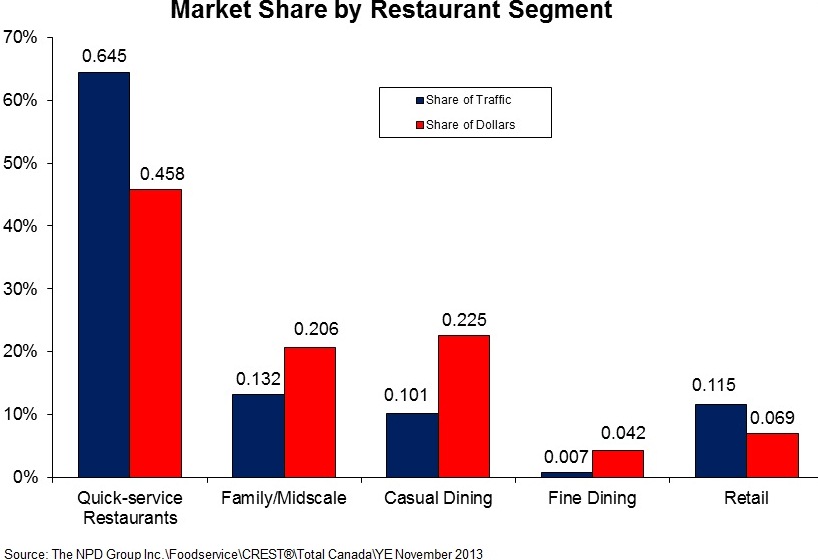

- Commercial foodservice

Operations whose primary business is food and beverage.

- commercial foodservice

Operations whose primary business is food and beverage.

- commercial general liability insurance

The most common type of liability insurance that provides coverage for litigation; generally legal costs and personal injury settlements arising from a lawsuit are covered.

- Commercial general liability insurance

The most common type of liability insurance that provides coverage for litigation; generally legal costs and personal injury settlements arising from a lawsuit are covered.

A DMO that represents a city or town.

- community destination marketing organization (CDMO)

A DMO that represents a city or town.

Small-scale gaming establishments, typically in the form of bingo halls.

- community gaming centres (CGCs)

Small-scale gaming establishments, typically in the form of bingo halls.

- Competitive set

A marketing term used to identify a group of hotels that include all competitors that a hotel’s guests are likely to go to consider an alternative to the company (minimum of three).

- competitive set

A marketing term used to identify a group of hotels that include all competitors that a hotel’s guests are likely to go to consider an alternative to the company (minimum of three).

- Conferences

Business events that have specific themes and are held for smaller groups than conventions.

- conferences

Business events that have specific themes and are held for smaller groups than conventions.

- Conflict management

The practice of being able to identify and handle conflicts sensibly, fairly, and efficiently.

- conflict management

The practice of being able to identify and handle conflicts sensibly, fairly, and efficiently.

- conscious consumerism

Refers to consumers using their purchasing power to shape the world according to their values and beliefs.

- Conscious consumerism

Refers to consumers using their purchasing power to shape the world according to their values and beliefs.

- consideration

The value exchanged between parties in the contract (money, services, or waiving legal rights).

- Consideration

The value exchanged between parties in the contract (money, services, or waiving legal rights).

- conventions

Business events that generally have very large attendance, are held annually in different locations each year, and usually require a bidding process.

- Conventions

Business events that generally have very large attendance, are held annually in different locations each year, and usually require a bidding process.

- costs per occupied room (CPOR)

All the costs associated with making a room ready for a guest (linens, cleaning costs, guest amenities).

- Costs per occupied room (CPOR)

All the costs associated with making a room ready for a guest (linens, cleaning costs, guest amenities).

- cross-utilization

When a menu is created to make multiple uses of a small number of staple pantry ingredients, helping to keep food costs down.

- Cross-utilization

When a menu is created to make multiple uses of a small number of staple pantry ingredients, helping to keep food costs down.

- Crown land

Land owned and managed by either the provincial or federal governments.

- Crown land tenure

Rights given to commercial organizations to operate on Crown land.

- Cruise BC

A multi-stakeholder organization responsible for the development and marketing of British Columbia as a cruise destination.

- Cruise Lines International Association (CLIA)

The world’s largest cruise industry trade association with representation in North and South America, Europe, Asia and Australasia.

- culinary tourism

Tourism experiences where the key focus is local and regional food and drink, often highlighting the heritage of products involved and techniques associated with their production.

- Culinary tourism

Tourism experiences where the key focus is local and regional food and drink, often highlighting the heritage of products involved and techniques associated with their production.

- cultural commodification

The drive toward putting a monetary value on aspects of a culture.

- Cultural commodification

The drive toward putting a monetary value on aspects of a culture.

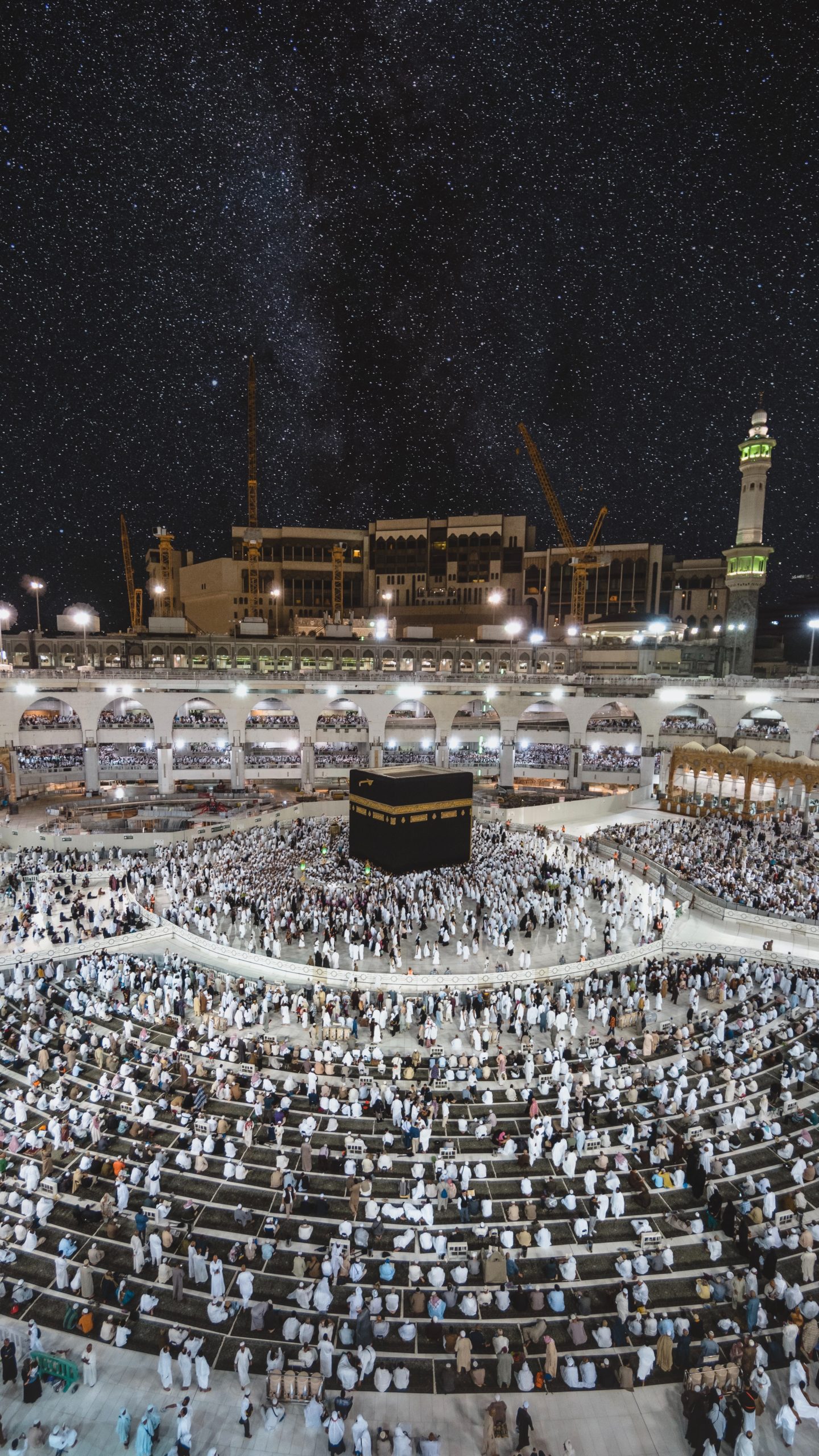

- cultural/heritage tourism

When tourists travel to a specific destination in order to participate in a cultural or heritage-related event.

- Cultural/heritage tourism

When tourists travel to a specific destination in order to participate in a cultural or heritage-related event.

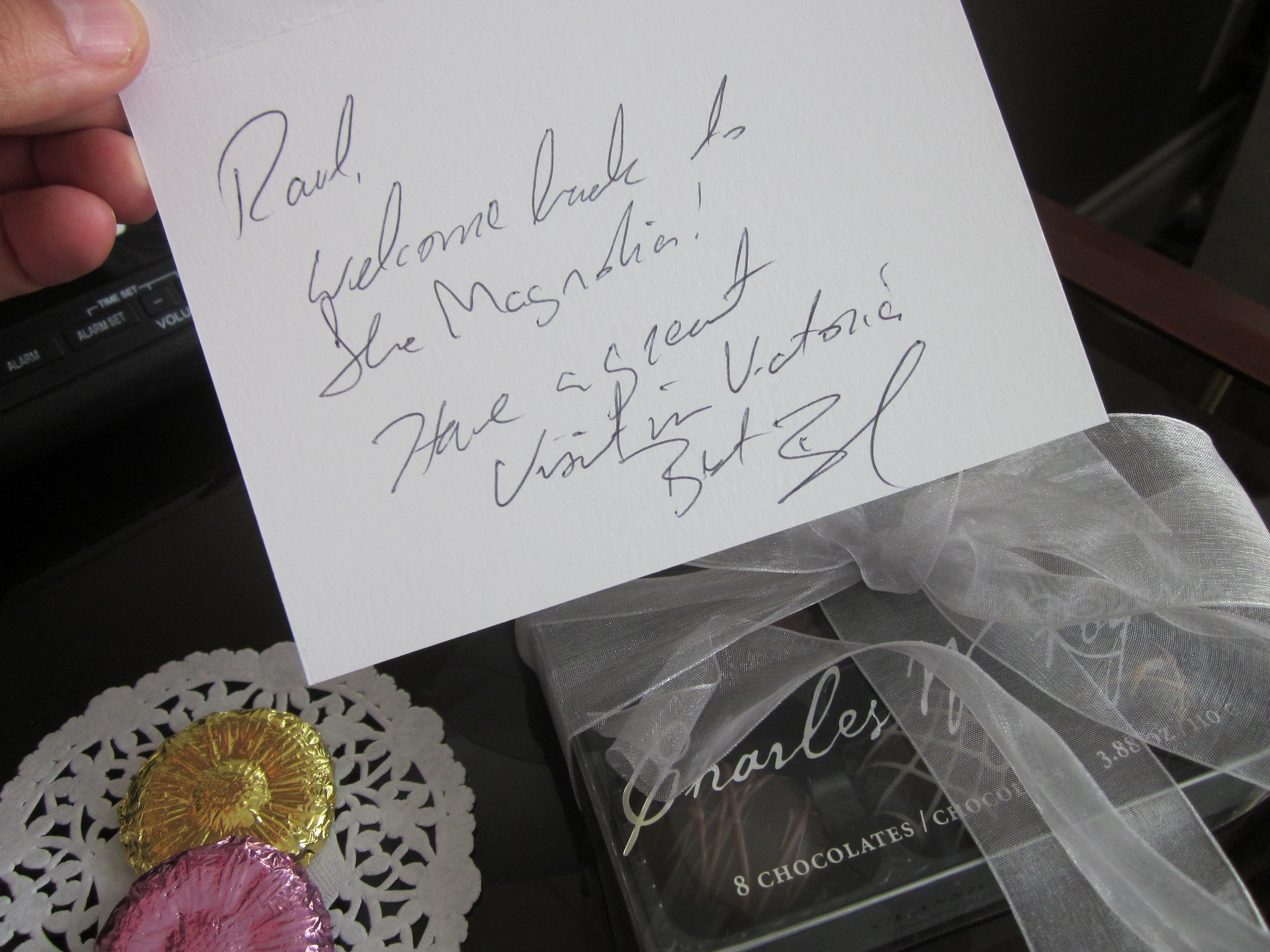

- Customer lifetime value (CLV)

A view of customer relationships that looks at long-term cycle of customer interactions, rather than at single transactions.

- customer lifetime value (CLV)

A view of customer relationships that looks at long-term cycle of customer interactions, rather than at single transactions.

- customer needs

Gaps between what customers have and what they would like to have.

- Customer needs

Gaps between what customers have and what they would like to have.

- customer orientation

Positioning a business or organization so that customer interests and value are the highest priority.

- Customer orientation

Positioning a business or organization so that customer interests and value are the highest priority.

- customer relationship management (CRM)

A strategy used by businesses to select customers and to maintain relationships with them to increase their lifetime value to the business.

- Customer relationship management (CRM)

A strategy used by businesses to select customers and to maintain relationships with them to increase their lifetime value to the business.

- customer wants

Needs of which customers are aware.

- Customer wants

Needs of which customers are aware.

- Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People

A 2007 statement that set forth the minimum standards for the survival, dignity, and well-being of the indigenous peoples of the world.

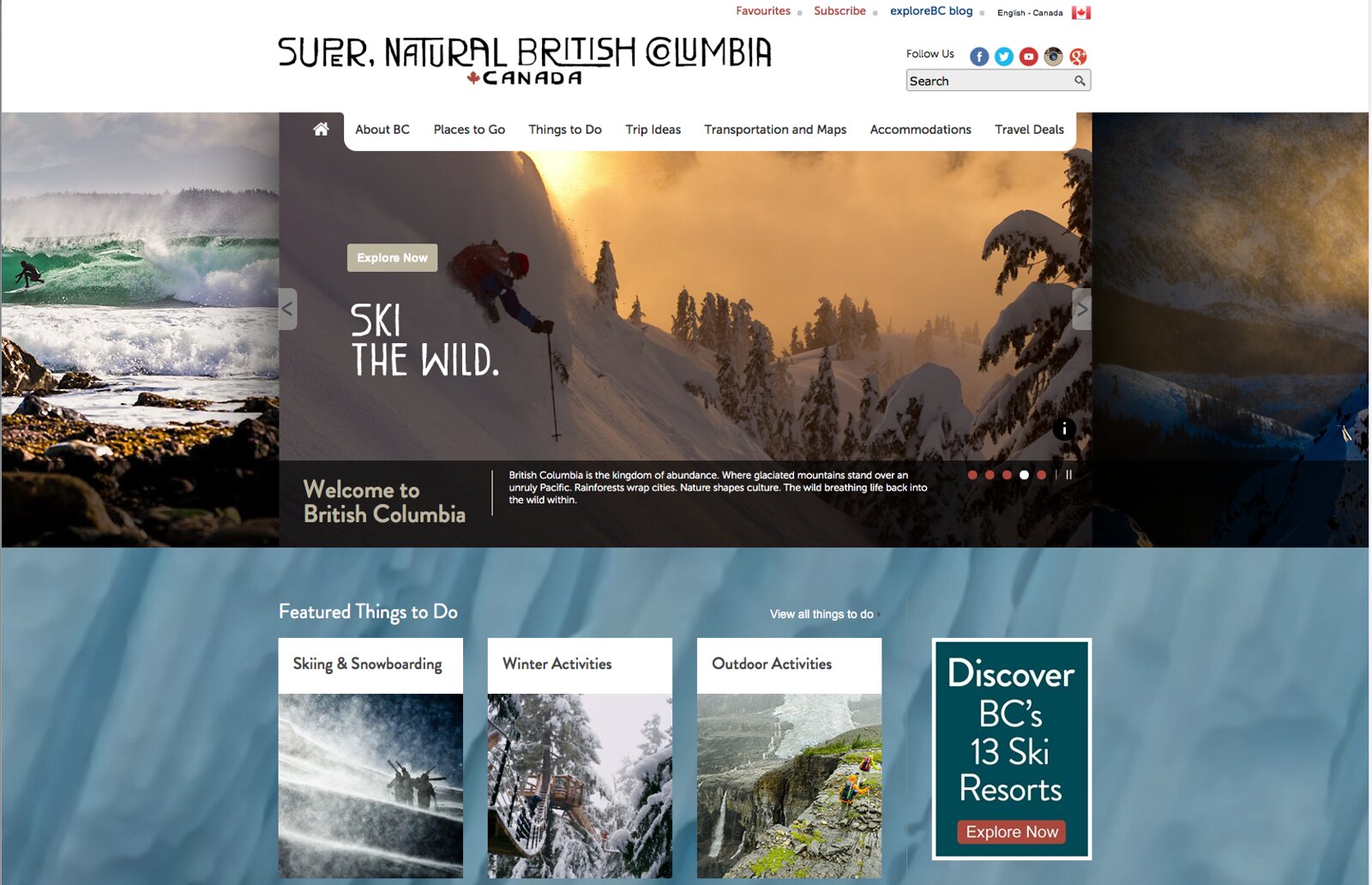

- Destination BC

The provincial destination marketing organization (DMO) responsible for tourism marketing and development in BC, formerly known as Tourism BC.

- Destination Canada

Destination Canada, is a Crown corporation previously known as the Canadian Tourism Commission (CTC). Destination Canada is responsible for promoting Canada in both domestic and foreign markets. Destination Canada also works with private companies, travel services providers, meeting professionals, and government organizations to help leverage Canada’s tourism brand and provide the industry with valuable visitor data.

- destination management company (DMC)

A company that creates and executes corporate travel and event packages designed for employee rewards or special retreats.

- Destination management company (DMC)

A company that creates and executes corporate travel and event packages designed for employee rewards or special retreats.

- destination marketing organization (DMO)

Also known as a destination management organization; includes national tourism boards, state/provincial tourism offices, and community convention and visitor bureaus.

- Destination marketing organization (DMO)

Also known as a destination management organization; includes national tourism boards, state/provincial tourism offices, and community convention and visitor bureaus.

- Destination mountain resorts

Large-scale mountain resorts where the draw is the resort itself; usually the resort offers all services needed in a tourism destination.

- destination mountain resorts

Large-scale mountain resorts where the draw is the resort itself; usually the resort offers all services needed in a tourism destination.

- dine-and-dash

The term commonly used in the industry for when a patron eats but does not pay for his or her meal.

- Dine-and-dash

The term commonly used in the industry for when a patron eats but does not pay for his or her meal.

- direct climate impacts

What will occur directly as a result of changes to the climate such as extreme weather events.

- Direct climate impacts

What will occur directly as a result of changes to the climate such as extreme weather events.

- Dive Industry Association of BC

A marketing and advocacy organization protecting the interests of divers, dive shops, guides, dive instructors, and diving destinations in BC.

- diversity

A term used by some in the industry to describe the makeup of the industry in a positive way; acknowledging that tourism is a diverse compilation of a multitude of businesses, services, organizations, and communities.

- Diversity

A term used by some in the industry to describe the makeup of the industry in a positive way; acknowledging that tourism is a diverse compilation of a multitude of businesses, services, organizations, and communities.

- Domestic Independent Traveler (DIT)

a person travelling in their home country that creates their own itinerary and travel plans with out the aid of a travel agent or organization, this may include using the resources of online and bricks and motor supplier resources.

- domestic independent traveller (DIT)

A person travelling in their home country who creates their own itinerary and travel plans without the aid of a travel agent or organization. This may include using the resources of online and brick-and-mortar suppliers.

- duty to care

The relationship between the plaintiff and defendant (monetary, supervisory, custodial or otherwise) that requires a responsibility on behalf of one party to care for the other.

- Duty to care

The relationship between the plaintiff and defendant (monetary, supervisory, custodial or otherwise) that requires a responsibility on behalf of one party to care for the other.

- e-commerce

Electronic commerce; performing business transactions online while collecting rich data about consumers.

- E-commerce

Electronic commerce; performing business transactions online while collecting rich data about consumers.

A model that calculates the amount of natural resources needed to support society at its current standard of living.

- Ecological footprint

A model that calculates the amount of natural resources needed to support society at its current standard of living.

- emerging markets

Markets for BC that are monitored and explored by Destination BC — China, India, and Mexico.

- Emerging markets

Markets for BC that are monitored and explored by Destination BC -- China, India, and Mexico.

- Employment Standards Act

Defines legal requirements around employment such as minimum wage, breaks, meal times, vacation pay, statutory holidays, age of employment, and leave from work.

- entertainment

(As it relates to tourism) includes attending festivals, events, fairs, spectator sports, zoos, botanical gardens, historic sites, cultural venues, attractions, museums, and galleries.

- Entertainment

(As it relates to tourism) includes attending festivals, events, fairs, spectator sports, zoos, botanical gardens, historic sites, cultural venues, attractions, museums, and galleries.

- Environmental accreditation or certification

A voluntary system that establishes environmental standards and regulates adherence to reducing environmental impacts.

- Environmental Assessment Office

The provincial agency responsible for reviewing large projects occurring on Crown land in BC.

- environmental management

Policies and procedures designed to protect natural values while providing a framework for use.

- Environmental management

Policies and procedures designed to protect natural values while providing a framework for use.

- environmental stewardship

The practice of ensuring natural resources are conserved and used responsibly in a way that balances the needs of various groups.

- Environmental stewardship

The practice of ensuring natural resources are conserved and used responsibly in a way that balances the needs of various groups.

- Eskimo

A term once used by non-Inuit people to describe Inuit people; no longer considered appropriate.

- ethnic restaurant

A restaurant based on the cuisine of a particular region or country, often reflecting the heritage of the head chef or owner.

- Ethnic restaurant

A restaurant based on the cuisine of a particular region or country, often reflecting the heritage of the head chef or owner.

- event

A happening at a given place and time, usually of some importance, celebrating or commemorating a special occasion; can include mega-events, special events, hallmark events, festivals, and local community events.

- Event

A happening at a given place and time, usually of some importance, celebrating or commemorating a special occasion; can include mega-events, special events, hallmark events, festivals, and local community events.

- Excursionist

same-day visitors in a destination. Their trip typically ends on the same day when they leave the destination.

- excursionist

A same-day visitor to a destination. Their trip typically ends on the same day when they leave the destination.

- experiential learning

Learning that takes place when a student directly participates in experiences designed for a learning purpose. Takes place both inside and outside of the classroom, and involves reflection as well as action.

- Experiential learning

Learning that takes place when a student directly participates in experiences designed for a learning purpose; takes place both inside and outside of the classroom; and involves reflection as well as action.

- export-ready criteria

The highest level of market readiness, with sophisticated travel distribution trade channels, to attract out-of-town visitors and highly reliable service standards, particularly with groups.

- Export-ready criteria

The highest level of market readiness, with sophisticated travel distribution trade channels, to attract out-of-town visitors and highly reliable service standards, particularly with groups.

- exposure avoidance

A risk control technique that avoids any exposure to that particular risk.

- Exposure avoidance

A risk control technique that avoids any exposure to that particular risk.

- fad

Something taken up in a finite, short amount of time. Can represent a valuable business opportunity, but investment can be risky.

- Fad

Something taken up in a finite, short amount of time – can represent a valuable business opportunity, but investment can be risky.

- familiarization tours (FAMs)

Tours provided to overseas travel agents, travel agencies, RTOs, and others to provide information about a certain product at no or minimal cost to participants. The short form is pronounced like the start of the word "family" (not as each individual letter).

- Familiarization tours (FAMs)

Tours provided to overseas travel agents, travel agencies, RTOs, and others to provide information about a certain product at no or minimal cost to participants — the short form is pronounced like the start of the word family (not as each individual letter).

- family/casual restaurant

A restaurant type that is typically open for all three meal periods, offering affordable prices and able to serve diverse tastes and accommodate large groups.

- Family/casual restaurant

A restaurant type that is typically open for all three meal periods, offering affordable prices and able to serve diverse tastes and accommodate large groups.

- festival

Public event that features multiple activities in celebration of a culture, an anniversary or historical date, art form, or product (food, timber, etc.).

- Festival

Public event that features multiple activities in celebration of a culture, an anniversary or historical date, art form, or product (food, timber, etc.).

- Fine dining restaurant

Licensed food and beverage establishment characterized by high-end ingredients and preparations and highly trained service staff.

- fine dining restaurant

Licensed food and beverage establishment characterized by high-end ingredients and preparations and highly trained service staff.

- First Nation

One of the three recognized groups of Canada's Aboriginal peoples (along with Inuit and Métis).

- First Nations

One of the three recognized groups of Canada's Indigenous peoples (along with Inuit and Métis).

- First Nations land

Land under Aboriginal title or that is managed by First Nations.

- FirstHost

An Indigenous tourism workshop focusing on hospitality service delivery and the special importance of the host, guest, and place relationship.

- Food and beverage (F & B)

Type of operation primarily engaged in preparing meals, snacks, and beverages, to customer order, for immediate consumption on and off the premises.

- food and beverage (F & B)

Type of operation primarily engaged in preparing meals, snacks, and beverages, to customer order, for immediate consumption on and off the premises.

- Food cost

Price including freight charges of all food served to the guest for a price (does not include food and beverages given away, which are quality or promotion costs).

- food cost

Price including freight charges of all food served to the guest for a price (does not include food and beverages given away, which are quality or promotion costs).

- Food primary

A licence required to operate a restaurant whose primary business is serving food (rather than alcohol).

- food primary

A licence required to operate a restaurant whose primary business is serving food (rather than alcohol).

- Foodie

A term (often used by the person themselves) to describe a food and beverage enthusiast.

- foodie

A term (often used by the person themselves) to describe a food and beverage enthusiast.

- Foreign Independent Traveler (FIT)

a person travelling outside their home country that creates their own itinerary and travel plans with out the aid of a travel agent or organization, this may include using the resources of online and bricks and motor supplier resources.

- foreign independent traveller (FIT)

A person travelling outside their home country who creates their own itinerary and travel plans without the aid of a travel agent or organization. This may include using the resources of online and brick-and-mortar suppliers.

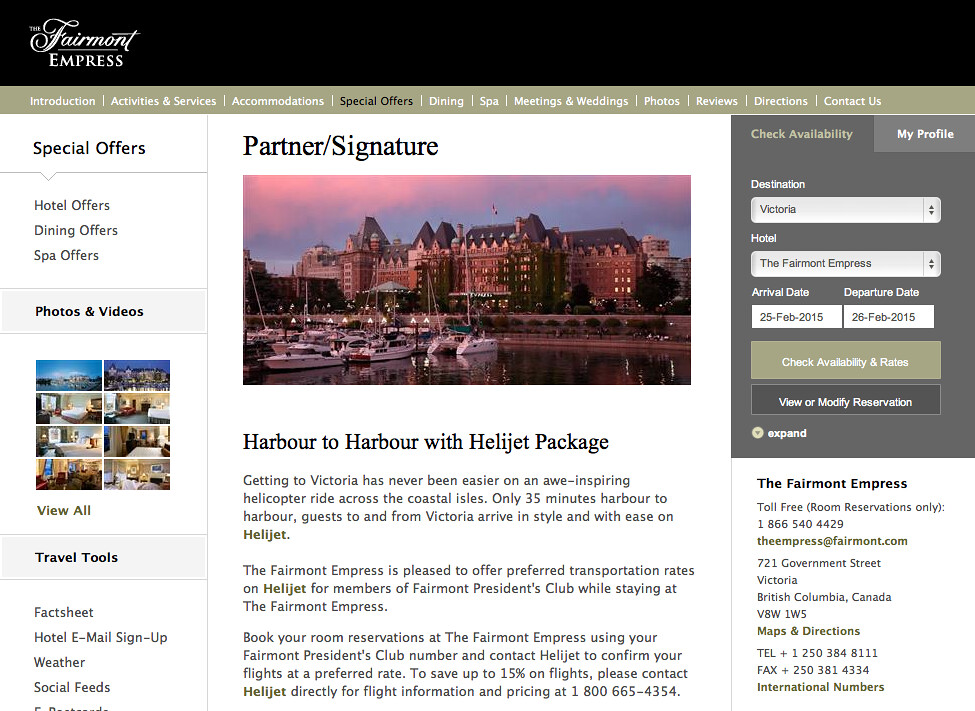

- Fractional ownership

A financing model that developers use to finance hotel builds by selling units in one-eighth to one-quarter shares.

- fractional ownership

A financing model that developers use to finance hotel builds by selling units in one-eighth to one-quarter shares.

- Fragmentation

A phenomenon observed by some industry insiders whereby the tourism industry is unable to work together towards common marketing and lobbying (policy-setting) objectives.

- fragmentation

A phenomenon observed by some industry insiders whereby the tourism industry is unable to work together towards common marketing and lobbying (policy-setting) objectives.

- Franchise

Enables individuals or investment companies to build or purchase a business and then buy or lease a brand name under which to operate; also can include reservation systems and marketing tools.

- franchise

Enables individuals or investment companies to build or purchase a business and then buy or lease a brand name under which to operate; also can include reservation systems and marketing tools.

- Franchisee

An individual or company buying or leasing a franchise.

- franchisee

An individual or company buying or leasing a franchise.

- Franchisor

A company that sells franchises.

- franchisor

A company that sells franchises.

- Front of house

Public areas of the establishment; in quick service it includes the ordering and product serving area.

- front of house

Public areas of the establishment. In quick service, it includes the ordering and product serving area.

- Full-service restaurants

Casual and fine dining restaurants where guests order food seated and pay after they have finished their meal.

- full-service restaurants

Casual and fine dining restaurants where guests order food seated and pay after they have finished their meal.

- Fully independent traveller (FIT)

A traveller who makes his or her own arrangements for accommodations, transportation, and tour components; is independent of a group.

- fully independent traveller (FIT)

A traveller who makes his or her own arrangements for accommodations, transportation, and tour components and is independent of a group.

- Globalization

The movement of goods, ideas, values, and people around the world.

- globalization

The movement of goods, ideas, values, and people around the world.

- Greenwashing

The act of claiming a product is "green" or environmentally friendly solely for marketing and promotional purposes.

- greenwashing

The act of claiming a product is "green" or environmentally friendly solely for marketing and promotional purposes.

- Guide Outfitters Association of BC (GOABC)

Established in 1966 to promote and preserve the interests of guide outfitters, who take hunters out into wildlife habitat; publishers of Mountain Hunter magazine.

- HelloBC

Online travel services platform of Destination BC providing information to the visitor and potential visitor for trip planning purposes.

- Heterogeneous

Variable, a generic difference shared by all services.

- heterogeneous

Variable: a generic difference shared by all services.

- Hidden job market

Employment opportunities that aren't posted through traditional channels, but rather arise because of a person's connections and relationships.

- hidden job market

Employment opportunities that aren't posted through traditional channels, but rather arise because of a person's connections and relationships.

- Homogenizing

Making the same, as in the effect of tourism helping to spread Western values, rendering one culture indistinguishable from the next.

- homogenizing

Making the same, i.e., the effect of tourism helping to spread Western values, rendering one culture indistinguishable from the next.

- Hospitality

The accommodations and food and beverage industry groupings.

- hospitality

The accommodations and food and beverage industry groupings.

- Hotel Association of Canada (HAC)

The national trade organization advocating on behalf of over 8,500 hotels.

- Hotel Guest Registration Act

Requires hotel keepers to register guests appropriately, which includes noting the guest’s arrival and departure dates, home address, and type and licence number of any vehicle.

- Hotel Keepers Act

Allows an accommodation provider to place a lien on guest property for unpaid bills, limits the liability of the hotel keeper when guest property is stolen and/or damaged, and gives the provider authority to require guests to leave in the event of a disturbance.

- Hotel type

A classification determined primarily by the size and location of the building structure, and then by the function, target markets, service-level, other amenities and industry standards.

- hotel type

A classification determined primarily by the size and location of the building structure, and then by the function, target markets, service-level, other amenities and industry standards.

- In country

A term to describe using a local-ownership approach in order for the wealth generated from tourism to stay in a destination.

- in country

A term to describe using a local-ownership approach in order for the wealth generated from tourism to stay in a destination.

- Inbound tour operator

An operator who packages products together to bring visitors from external markets to a destination.

- inbound tour operator

An operator who packages products together to bring visitors from external markets to a destination.

- Incentive travel

A global management tool that uses an exceptional travel experience to motivate and/or recognize participants for increased levels of performance in support of organizational goals.

- incentive travel

A global management tool that uses an exceptional travel experience to motivate and/or recognize participants for increased levels of performance in support of organizational goals.

- Indian (or Native Indian)

A legal term in Canada. It has been used to describe Indigenous people, but is now considered inappropriate.

- Indigenous cultural experiences

Experiences that are offered in a manner that is appropriate, respectful, and true to the Indigenous culture being portrayed.

- Indigenous cultural tourism

Indigenous tourism that incorporates Indigenous culture as a significant portion of the experience in a manner that is appropriate, respectful, and true (see Indigenous cultural experiences).

- Indigenous peoples

Groups specially protected in international or national legislation as having a set of specific rights based on their historical ties to a particular territory, and their cultural or historical distinctiveness from other populations. Indigenous peoples are recognized in the Canadian Constitution Act as comprising three groups: First Nations, Métis, and Inuit.

- Indigenous tourism

Tourism businesses that are majority owned and operated by First Nations, Métis, and Inuit.

- Indigenous Tourism Association of BC (ITBC)

the organization responsible for developing and marketing Indigenous tourism experiences in BC in a strategic way; marketing stakeholder members are over 51% owned and operated by First Nations, Métis, and Inuit

- Indigenous Tourism Association of Canada (ITAC)

A consortium of over 20 Indigenous tourism industry organizations and government representatives from across Canada.

- Indigenous Tourism BC (ITBC)

The organization responsible for developing and marketing Indigenous tourism experiences in B.C. in a strategic way. Marketing stakeholder members are over 51% owned and operated by First Nations, Métis, and Inuit.

- Indirect environmental change impacts

What will occur indirectly as a result of climate change, including damages to infrastructure.

- indirect environmental change impacts

What will occur indirectly as a result of climate change, including damages to infrastructure.

- Influencers

individuals with a strong online presence and following who can use their knowledge, authority, and relationships with followers to share brand-aligned content and inspire travellers to visit or purchase

- influencers

Individuals with a strong online presence and following who can use their knowledge, authority, and relationships with followers to share brand-aligned content and inspire travellers to visit destinations or purchase products.

- Informational interview

A short appointment where you learn about an employer, or a specific role, from someone already established in the field.

- informational interview

A short appointment where you learn about an employer or a specific role from someone already established in the field.

- Inherent risk

Risk that is inherent to the activity and that cannot be removed.

- inherent risk

Risk that is inherent to the activity and that cannot be removed.

- Injury

Proof the plaintiff did in fact receive an injury resulting in damage; can be bodily injury or property damage.

- injury

Proof the plaintiff did in fact receive an injury resulting in damage; can be bodily injury or property damage.

- inseparable

In relation to goods and services. Services cannot be separated from the service provider as the production and consumption happens at the same time.

- Intangible

Untouchable, a characteristic shared by all services.

- intangible

Untouchable: a characteristic shared by all services.

- Integrated marketing communications (IMC)

Planning and coordinating all the promotional mix elements and internet marketing so they are as consistent and as mutually supportive as possible.

- integrated marketing communications (IMC)

Planning and coordinating all the promotional mix elements and internet marketing so they are as consistent and as mutually supportive as possible.

- Intentional torts

Assault, battery, trespass, false imprisonment, nuisance, and defamation.

- intentional torts

Assault, battery, trespass, false imprisonment, nuisance, and defamation.

- Interactive media

Online and mobile platforms.

- interactive media

Online and mobile platforms.

- International Air Transport Association (IATA)

The trade association for the world’s airlines.

- International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO)

A specialized agency of the United Nations that creates global air policy and helps to develop industry capacity and safety.

- International Festivals and Events Association (IFEA)

Organization that supports professionals who produce and support celebrations for the benefit of their respective communities.

- Internship

Short-term, supervised work experience in a student’s field of interest for which the student may earn academic credit.

- internship

Short-term, supervised work experience in a student’s field of interest for which the student may earn academic credit.

- Interpersonal factors

The influence of cultures, social classes, family, and opinion leaders on consumers.

- interpersonal factors

The influence of cultures, social classes, family, and opinion leaders on consumers.

- Inuit

One of the three recognized groups of Canada's Indigenous peoples (along with First Nation and Métis), from the Arctic region of Canada.

- Larrakia Declaration

A set of principles developed to guide appropriate Indigenous tourism development.

- Liquor and Cannabis Regulation Branch (LCRB)

The BC government agency responsible for legislation and control of alcohol and cannabis sales, service, manufacture, import, and distribution in the province.

- Liquor Control and Licensing Act

Defines the ways in which alcohol can be made, imported, purchased, and consumed in BC.

- Liquor Control and Licensing Branch (LCLB)

The BC government agency responsible for legislation and control of alcohol sales, service, manufacture, import, and distribution in the province.

- Liquor primary licences

The type of licence needed in BC to operate a business that is in the primary business of selling alcohol (most pubs, nightclubs and cabarets fall into this category).

- liquor primary licences

The type of licence needed in BC to operate a business that is in the primary business of selling alcohol (most pubs, nightclubs and cabarets fall into this category).

- Loss reduction

A risk control technique that reduces the severity of the impact of the risk should it occur.

- loss reduction

A risk control technique that reduces the severity of the impact of the risk should it occur.

- Low-cost carrier (LCC)

An airline that competes on price, cutting amenities and striving for volume to achieve a profit.

- low-cost carrier (LCC)

An airline that competes on price, cutting amenities and striving for volume to achieve a profit.

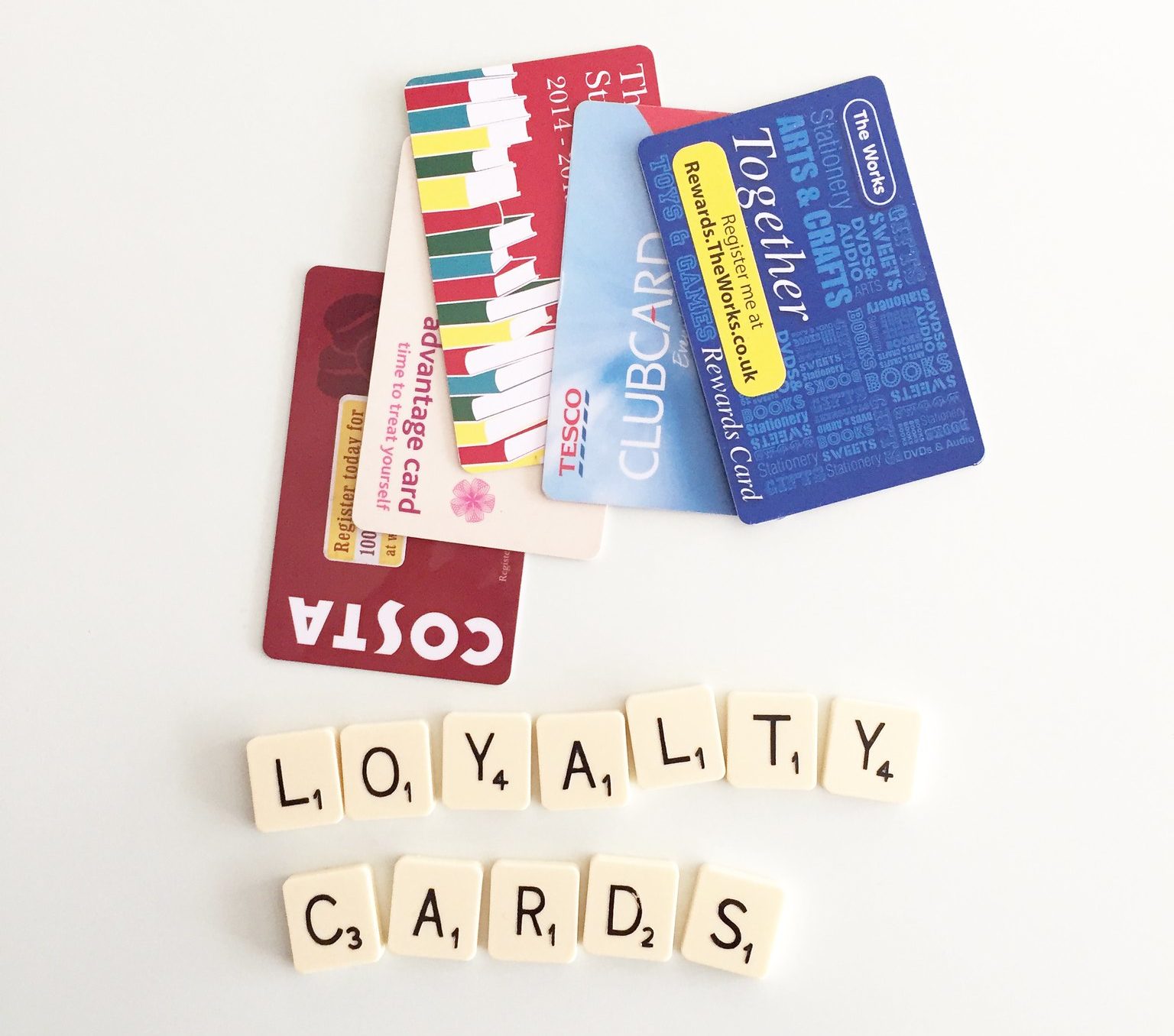

- Loyalty programs

Programs that identify and build databases of frequent customers to promote directly to them, and to reward and provide special services for those frequent customers.

- loyalty programs

Programs that identify and build databases of frequent customers to promote directly to them, and to reward and provide special services for those frequent customers.

- Marae

A communal or sacred centre that serves a religious and social purpose in Polynesian societies.

- marae

A communal or sacred centre that serves a religious and social purpose in Polynesian societies.

- Market segmentation

Specific groups of people with a similar profile, allowing marketers to target their messaging.

- market segmentation

Specific groups of people with a similar profile, allowing marketers to target their messaging.

- Market-ready business

A business that goes beyond visitor readiness to demonstrate strengths in customer service, marketing, pricing and payments policies, response times and reservations systems, and so on.

- market-ready business

A business that goes beyond visitor readiness to demonstrate strengths in customer service, marketing, pricing and payments policies, response times and reservations systems, and so on.

- Marketing

A continuous, sequential process through which management plans, researches, implements, controls, and evaluates activities designed to satisfy the customers’ needs and wants, and its own organization’s objectives.

- marketing

A continuous, sequential process through which management plans, researches, implements, controls, and evaluates activities designed to satisfy the customers’ needs and wants, and its own organization’s objectives.

- Marketing orientation

The understanding that a company needs to engage with its markets in order to refine its products and services, and promotional efforts.

- marketing orientation

The understanding that a company needs to engage with its markets in order to refine its products and services, and promotional efforts.

- Mass media

The use of channels that reach very large markets.

- mass media

The use of channels that reach very large markets.

- Meeting Professionals International (MPI)

A membership-based professional development organization for meeting meeting and event planners.

- Meetings, conventions, and incentive travel (MCIT)

All special events with programming aimed at a business audience.

- meetings, conventions, and incentive travel (MCIT)

All special events with programming aimed at a business audience.

- Métis

One of the three recognized groups of Canada's Indigenous peoples (along with First Nation and Inuit), meaning "to mix."

- Ministry of Environment

The provincial ministry responsible for the environment in BC.

- Ministry of Environment and Climate Change Strategy

The provincial ministry responsible for the environment in BC.

- MINT

An acronym for the countries of Mexico, Indonesia, Nigeria, and Turkey.

- Moment of truth

When a customer’s interaction with a front line employee makes a critical difference in their perception of that company or destination.

- moment of truth

When a customer’s interaction with a front line employee makes a critical difference in their perception of that company or destination.

- Monoculture

A farming practice that depletes the soil and encourages the use of pesticides and fertilizers for increased production.

- monoculture

A farming practice that depletes the soil and encourages the use of pesticides and fertilizers for increased production.

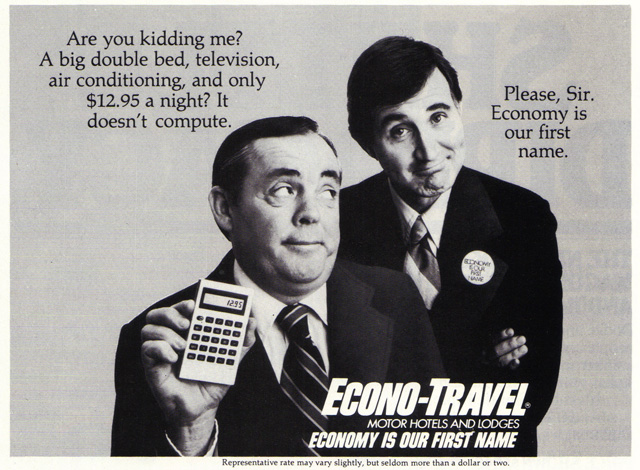

- motel

A term popular in the last century, combining the words "motor hotel"; typically designed to provide ample parking and easy access to rooms from the parking lot.

- Motel

A term popular in the last century, combining the words "motor hotel"; typically designed to provide ample parking and easy access to rooms from the parking lot.

- National Airports Policy (NAP)

The 1994 policy that saw transfer of 150 airports from federal control to communities and other local agencies, essentially deregulating the industry.

- Nature-based tourism

Tourism activities where the motivator is immersion in the natural environment; the focus is often on wildlife and wilderness area.

- nature-based tourism

Tourism activities where the motivator is immersion in the natural environment; the focus is often on wildlife and wilderness area.

- Nearby markets

Markets for BC, identified by Destination BC as BC, Alberta, and Washington State, characterized by high volume and strong repeat visitation.

- nearby markets

Markets for BC, identified by Destination BC as BC, Alberta, and Washington State, characterized by high volume and strong repeat visitation.

- Negligence

Failing to meet a reasonable standard of care toward others despite being required to do so.

- negligence

Failing to meet a reasonable standard of care toward others despite being required to do so.

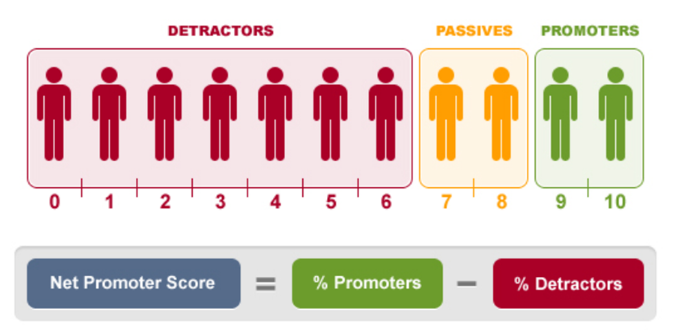

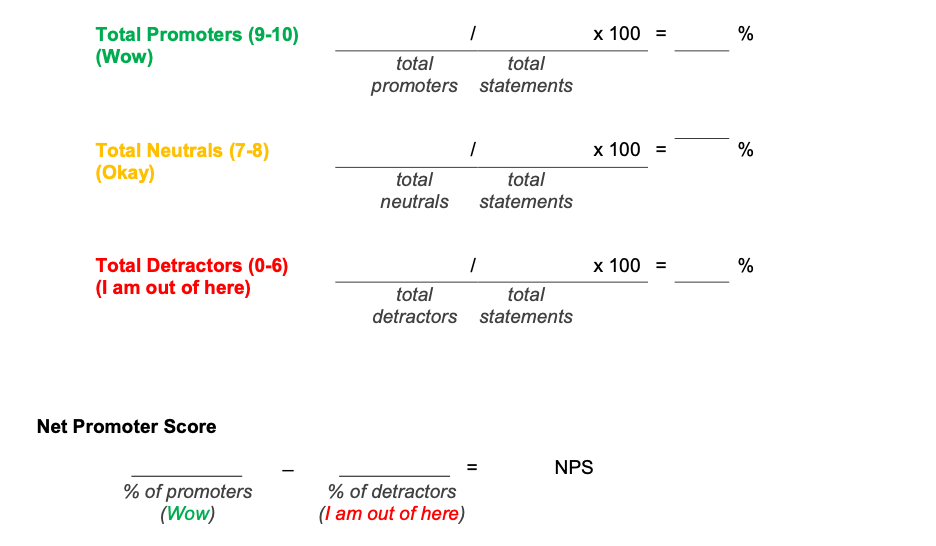

- Net promoter score (NPS)

A metric designed to monitor customer engagement, reflecting the likelihood that travellers will recommend a destination to friends, family, or colleagues.

- net promoter score (NPS)

A metric designed to monitor customer engagement, reflecting the likelihood that travellers will recommend a destination to friends, family, or colleagues.

- Networking

Creating relationships within a sector for the purpose of enhancing and developing one’s professional identity.

- networking

Creating relationships within a sector for the purpose of enhancing and developing one’s professional identity.

- Next Eleven

A term for the countries Bangladesh, Egypt, Indonesia, Iran, Mexico, Nigeria, Pakistan, the Philippines, South Korea, Turkey, and Vietnam.

- Non-commercial foodservice

Establishments where food is served, but where the primary business is not food and beverage service.

- non-commercial foodservice

Establishments where food is served, but where the primary business is not food and beverage service.

- North American Indian

A term used to describe First people in the United States, still used today.

- North American Industry Classification System (NAICS)

A way to group tourism activities based on similarities in business practices, primarily used for statistical analysis.

- Occupancy

Percentage of all guest rooms in the hotel that are occupied at a given time.

- occupancy

Percentage of all guest rooms in the hotel that are occupied at a given time.

- Occupiers Liability Act

Specifies responsibilities for those that occupy a premise such as a house, building, resort, or property to others on their property.

- Off-road recreational vehicle (ORV)

Any vehicle designed to travel off of paved roads and on to trails and gravel roads, such as an ATV (all-terrain vehicle) or Jeep.

- off-road recreational vehicle (ORV)

Any vehicle designed to travel off of paved roads and on to trails and gravel roads, such as an ATV (all-terrain vehicle) or Jeep.

- Online travel agent (OTA)

A service that allows the traveller to research, plan, and purchase travel without the assistance of a person, using the internet on sites such as Expedia.ca or Hotels.com.

- online travel agent (OTA)

A service that allows the traveller to research, plan, and purchase travel without the assistance of a person, using the internet on sites such as Expedia.ca or Hotels.com.

- Open skies

A set of policies that enable commercial airlines to fly in and out of other countries.

- open skies

A set of policies that enable commercial airlines to fly in and out of other countries.

- Operating supplies

Generally includes reusable items including cutlery, glassware, china, and linen in full-service restaurants.

- operating supplies

Generally includes reusable items including cutlery, glassware, china, and linen in full-service restaurants.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)

An organization of 31 member countries who gather to discuss a range of policy issues, with a special committee dedicated to tourism.

- organizational culture

Ways of acting, values, and beliefs shared within an organization.

- Organizational culture

Ways of acting, values, and beliefs shared within an organization.

- Out-of-home (OOH)

Channels in four major categories: billboards, transit, alternative outdoor, and street furniture.

- out-of-home (OOH)

Channels in four major categories: billboards, transit, alternative outdoor, and street furniture.

- outbound tour operator

An operator who packages and sells travel products to people within a destination who want to travel abroad.

- Outbound tour operator

An operator who packages and sells travel products to people within a destination who want to travel abroad.

- outdoor recreation

Recreational activities occurring outside; generally in undeveloped area.

- Outdoor recreation

Recreational activities occurring outside; generally in undeveloped area.

- Outdoor Recreation Council of BC (ORC)

A not-for-profit organization that promotes the benefits of outdoor recreation, represents the community to government and the general public, advocates and educates about responsible land use, provides a forum for exchanging information, and connects different outdoor recreation groups.

- Parks Canada

The federal agency responsible for management of national parks, historic sites, and marine conservation areas.

- passenger load factor

A way of measuring how efficiently a transportation company uses their vehicles on any given day, calculated for a single flight by dividing the number of passengers by the number of seats.

- Passenger load factor

A way of measuring how efficiently a transportation company uses their vehicles on any given day, calculated for a single flight by dividing the number of passengers by the number of seats.

- passive customer

A guest who is satisfied (won't complain, but won't celebrate the business either).

- Passive customer

A guest who is satisfied (won't complain, but won't celebrate the business either).

- PEEST

An acronym for political, economic, environmental, social, and technological forces.

- Perceived risk

The perception of the risk level of the practice, activity, or event; varies greatly from person to person.

- perishable

Something that is only good for a short period of time, a characteristic shared by all services.

- Perishable

Something that is only good for a short period of time, a characteristic shared by all services.

- Personal attributes

Describe what you are like aa a person/employee, such as your attitude, personality type, and so on.

- personal attributes

Descriptions of what someone is like as a person/employee, such as their attitude, personality type, and so on.

- personal factors

The needs, wants, motivations, previous experiences, and objectives of consumers that they bring into the decision-making process.

- Personal factors

The needs, wants, motivations, previous experiences, and objectives of consumers that they bring into the decision-making process.

- PESTLE

An acronym for political, economic, social, technological, legal and environmental forces.

- pop-up restaurants

Temporary restaurants with a known expiry date hosted in an unusual location, which tend to be helmed by a well-known or up-and-coming chef and use word-of-mouth in their promotions.

- Pop-up restaurants

Temporary restaurants with a known expiry date hosted in an unusual location, which tend to be helmed by a well-known or up-and-coming chef and use word-of-mouth in their promotions.

- practicum

Practical experiences outside the classroom, supported by professionals in a workplace environment.

- Practicum

Practical experiences outside the classroom, supported by professionals in a workplace environment.

- PRICE concept

An acronym that helps marketers remember the need to plan, research, implement, control, and evaluate the components of their marketing plan.

- primary costs

Food, beverage, and labour costs for an F&B operation.

- Primary costs

Food, beverage, and labour costs for an F&B operation.

- print media

Newspapers, magazines, journals, and directories.

- Print media

Newspapers, magazines, journals, and directories.

- private land

Any land where private property rights apply in BC.

- Private land

Any land where private property rights apply in BC.

- Profit

The amount left when expenses (including corporate income tax) are subtracted from sales revenue.

- profit

The amount left when expenses (including corporate income tax) are subtracted from sales revenue.

- Psychographics

psychological characteristics, such as an individuals attitudes, beliefs, values, motivations, and behaviours

- psychographics

Psychological characteristics, such as an individuals attitudes, beliefs, values, motivations, and behaviours.

- Public galleries

Art galleries that do not generally collect or conserve works of art; rather, they focus on exhibitions of contemporary works as well as programs of lectures, publications and other events.

- public gallery

An art gallery that does not generally collect or conserve works of art. Rather, it focuses on exhibitions of contemporary works, as well as programs of lectures, publications, and other events.

- quick-service restaurant (QSR)

An establishment where guests pay before they eat; includes counter service, take-out, and delivery.

- Quick-service restaurant (QSR)

An establishment where guests pay before they eat; includes counter service, take-out, and delivery.

- Railway Safety Act

A 1985 Act to ensure the safe operation of railways in Canada.

- real risk

The actual risk of the practice, activity, or event; generally determined by statistical evidence.

- Real risk

The actual risk of the practice, activity, or event; generally determined by statistical evidence.

- receptive tour operator (RTO)

Someone who represents the products of tourism suppliers to tour operators in other markets in a business-to-business (B2B) relationship.

- Receptive tour operator (RTO)

Someone who represents the products of tourism suppliers to tour operators in other markets in a business-to-business (B2B) relationship.

- recreation

Activities undertaken for leisure and enjoyment.

- Recreation

Activities undertaken for leisure and enjoyment.

- regional destination marketing organization (RDMO)

In BC, one of the five DMOs that represent a specific tourism region.

- Regional destination marketing organization (RDMO)

In BC, one of the five DMOs that represent a specific tourism region.

- regional mountain resorts

Small resorts where the focus is on outdoor recreation for the local communities; may also draw tourists.

- Regional mountain resorts

Small resorts where the focus is on outdoor recreation for the local communities; may also draw tourists.

- Resort Associations Act

Developed to provide opportunities to fund a variety of promotional services for a community; the act defines what it means to be a resort community.

- Restaurants Canada

Representing over 30,000 food and beverage operations including restaurants, bars, caterers, institutions, and suppliers.

- revenue

Sales dollars collected from guests.

- Revenue

Sales dollars collected from guests.

- revenue per available room (RevPAR)

A calculation that combines both occupancy and ADR in one metric.

- Revenue per available room (RevPAR)

A calculation that combines both occupancy and ADR in one metric.

- ridesharing apps

Applications for mobile devices that allow users to share rides with strangers, undercutting the taxi industry.

- Ridesharing apps

Applications for mobile devices that allow users to share rides with strangers, undercutting the taxi industry.

- risk

The possibility for loss or harm.

- Risk

The possibility for loss or harm.

- risk management

Practices, policies, and procedures designed to minimize or eliminate unacceptable risks.

- Risk management

Practices, policies, and procedures designed to minimize or eliminate unacceptable risks.

- risk retention

The level of risk that is retained by the company through a conscious decision-making process.

- Risk retention

The level of risk that is retained by the company through a conscious decision-making process.

- risk transfer

A risk mitigation strategy where the risk is transferred to a third party through contract or insurance.

- Risk transfer

A risk mitigation strategy where the risk is transferred to a third party through contract or insurance.

- Sea Kayak Guides Alliance of BC

Representing more than 600 members in the commercial sea kayaking industry, providing operating standards, guide certification, advocacy, and government liaison services.

- self insuring

The practice of an operation retaining the risk rather than transferring through insurance; may be a conscious choice or a necessity based on lack of available coverage.

- Self insuring

The practice of an operation retaining the risk rather than transferring through insurance; may be a conscious choice or a necessity based on lack of available coverage.

- self-assessment

Informal and formal methods of gathering information about yourself to make career decisions.

- Self-assessment

Informal and formal methods of gathering information about yourself to make career decisions.

- service learning

Course-based, credit-bearing educational experience in which students participate in organized service that meets community needs, and reflect on the service.

- Service learning

Course-based, credit-bearing educational experience in which students participate in organized service that meets community needs, and reflect on the service.

- service recovery

What happens when a customer service professional takes actions that result in the customer being satisfied after a service failure has occurred.

- Service recovery

What happens when a customer service professional takes actions that result in the customer being satisfied after a service failure has occurred.

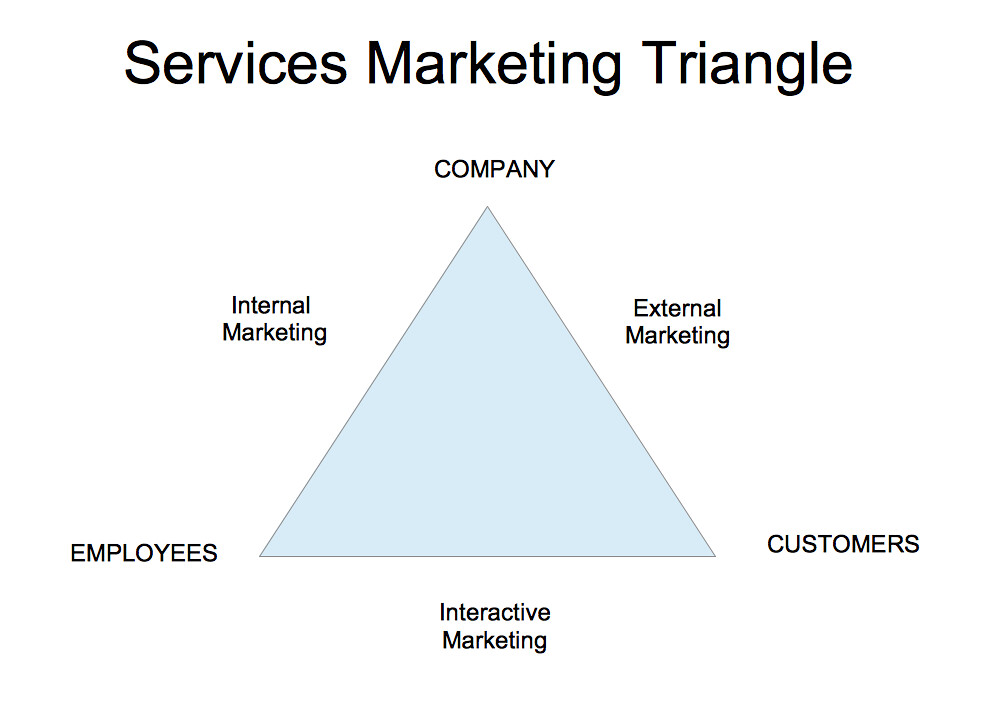

- services marketing

Marketing that specifically applies to services such as those provided by the tourism and hospitality industries, differs from the marketing of goods.

- Services marketing

Marketing that specifically applies to services such as those provided by the tourism and hospitality industries, differs from the marketing of goods.

- services marketing triangle

A model for understanding the relationship between the company, its employees, and the customer; differs from traditional marketing where the business speaks directly to the consumer.

- Services marketing triangle

A model for understanding the relationship between the company, its employees, and the customer; differs from traditional marketing where the business speaks directly to the consumer.

- SERVQUAL

A technique developed to measure service quality.

- Sharing economy

An internet-based economic system in which consumers share their resources, typically with people they don’t know, and typically in exchange for money.

- sharing economy

An internet-based economic system in which consumers share their resources, typically with people they don’t know, and typically in exchange for money.

- SMERF

An acronym for the social, military, educational, religious, and fraternal segment of the group travel market.

- Social Exchange Theory

describes how tourists and hosts’ behaviours change as a result of the perceived benefits and threats they create during interaction

- social exchange theory

A theory that describes how tourists' and hosts’ behaviours change as a result of the perceived benefits and threats they create during interaction.

- Social media

Refers to web-based and mobile applications used for social interaction and the exchange of content.

- social media

Refers to web-based and mobile applications used for social interaction and the exchange of content.

- Societal marketing

Marketing that recognizes a company's place in society and its responsibility to citizens (or at least the appearance thereof).

- societal marketing

Marketing that recognizes a company's place in society and its responsibility to citizens (or at least the appearance thereof).

- Society for Incentive Travel Excellence (SITE)

A global network of professionals dedicated to the recognition and development of motivational incentives and performance improvement.

- Sport tourism

Any activity in which people are attracted to a particular location as a participant, spectator, or visitor to sport attractions, or as an attendee of sport-related business meetings.

- sport tourism

Any activity in which people are attracted to a particular location as a participant, spectator, or visitor to sport attractions, or as an attendee of sport-related business meetings.

- Stewardship

having the duty of and then actively participating in the careful management of resources

- stewardship

Having the duty of and then actively participating in the careful management of resources.

- Sustainable development

Planning and development that is mindful of future generations while meeting society’s needs today.

- sustainable development

Planning and development that is mindful of future generations while meeting society’s needs today.

- Tangible

Goods the customer can see, feel, and/or taste ahead of payment.

- tangible

Goods the customer can see, feel, and/or taste ahead of payment.

- Technical skills

Skills and knowledge required to perform specific work.

- technical skills

Skills and knowledge required to perform specific work.

- Third space

A term used to describe F&B outlets enjoyed as "hang out" spaces for customers where guests and service staff co-create the experience.

- third space

A term used to describe F&B outlets enjoyed as "hangout" spaces for customers, where guests and service staff co-create the experience.

- Tip-out

The practice of having front-of-house staff pool their gratuities, or pay individually, to ensure back-of-house staff receive a percentage of the tips.

- tip-out

The practice of having front-of-house staff pool their gratuities, or pay individually, to ensure back-of-house staff receive a percentage of the tips.

- Top priority markets

Markets for BC identified as a top priority for Destination BC -- Ontario, California, Germany, Japan, United Kingdom, South Korea, Australia -- which are characterized by high revenue and high spend per visitor.

- top priority markets

Markets for BC identified as a top priority for Destination BC — Ontario, California, Germany, Japan, United Kingdom, South Korea, Australia — which are characterized by high revenue and high spend per visitor.

- Total Quality (TQ)

Integrating all employees, from management to front-level, in a process of continuous learning towards increasing customer satisfaction.

- total quality (TQ)

Integrating all employees, from management to front-level, in a process of continuous learning towards increasing customer satisfaction.

- Total quality management (TQM)

A process of setting service goals as a team.

- total quality management (TQM)

A process of setting service goals as a team.

- Tour operator

An operator who packages suppliers together (hotel + activity) or specializes in one type of activity or product.

- tour operator

An operator who packages suppliers together (hotel + activity) or specializes in one type of activity or product.

- Tourism

Tourism according the the UNWTO is a social, cultural and economic phenomenon which entails the movement of people to countries or places outside their usual environment for personal or business/professional purposes.

- tourism

Tourism according the the UNWTO is a social, cultural and economic phenomenon which entails the movement of people to countries or places outside their usual environment for personal or business/professional purposes.

- Tourism carrying capacity (TCC)

The maximum number of people that can visit a specific habitat in a set period of time without negative impacts, and without compromising the visitor experience.

- tourism carrying capacity (TCC)

The maximum number of people that can visit a specific habitat in a set period of time without negative impacts, and without compromising the visitor experience.

- Tourism Industry Association of BC (TIABC)

A membership-based advocacy group formerly known as the Council of Tourism Associations of BC (COTA).

- Tourism Industry Association of Canada (TIAC)

The national industry advocacy group.

- Tourism marketing system

An approach that guides the planning, execution, and evaluation of tourism marketing efforts (PRICE concept is an approach to this).

- tourism marketing system

An approach that guides the planning, execution, and evaluation of tourism marketing efforts (PRICE concept is an approach to this).

- Tourism paradox

The concept that tourism operations destroy its very requirements for success -- a pristine natural environment.

- tourism paradox

The concept that tourism operations destroy its very requirements for success: a pristine natural environment.

- Tourism services

Other services that work to support the development of tourism and the delivery of guest experiences.

- tourism services

Other services that work to support the development of tourism and the delivery of guest experiences.

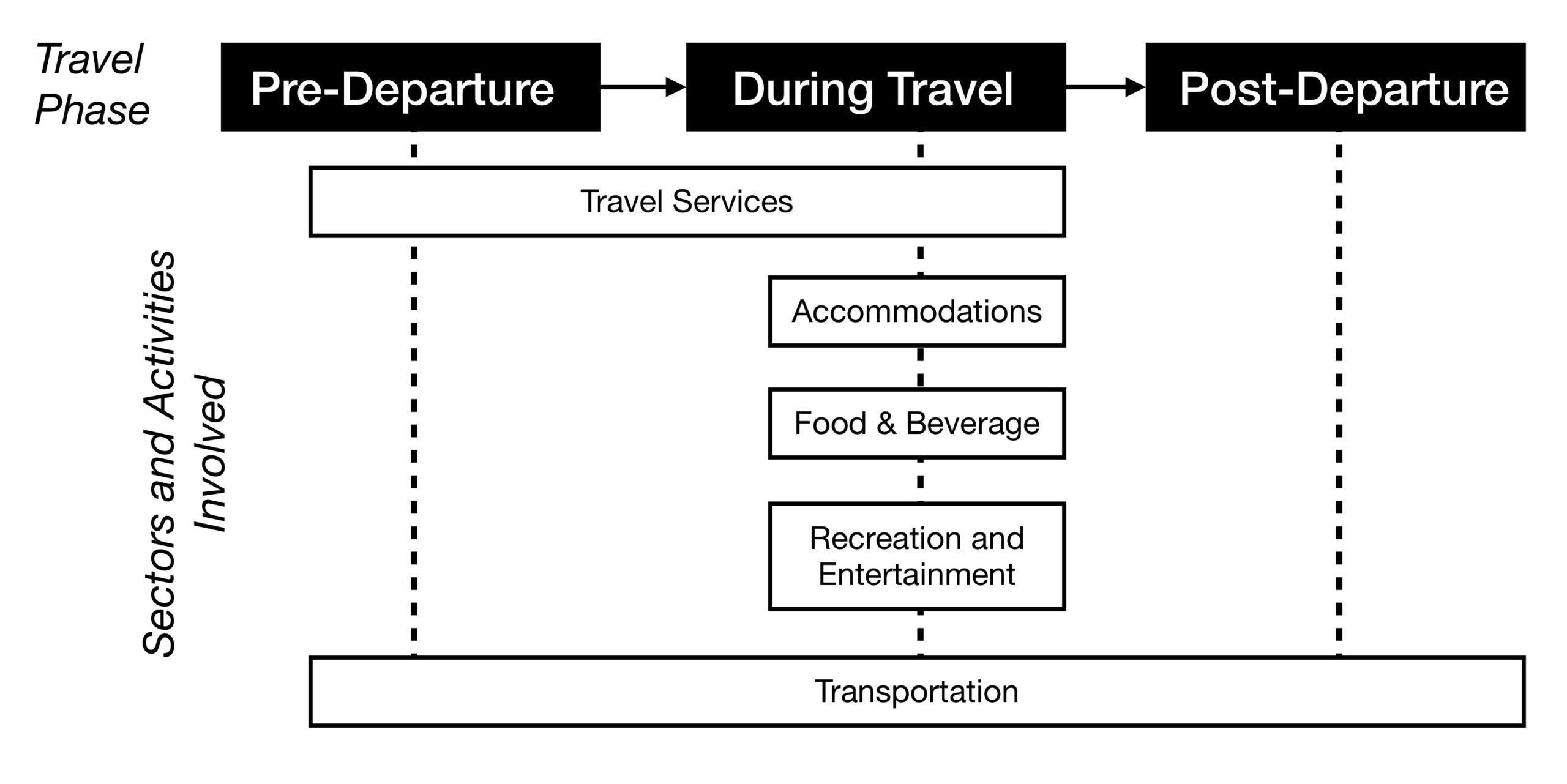

- Tourism Supply Chain

the combination of sectors that supply and distribute the needed tourism products, services, and activities within the tourism system

- tourism supply chain

The combination of sectors that supply and distribute the needed tourism products, services, and activities within the tourism system.

- Tourism world-making

The way in which a place or culture is marketed and/or presented to tourists.

- tourism world-making

The way in which a place or culture is marketed and/or presented to tourists.

- tourist

Someone who travels at least 80 kilometres from his or her home for at least 24 hours, for business or pleasure or other reasons; can be further classified as domestic, inbound, or outbound.

- tourist attraction

A places of interest that pulls visitors to a destination, open to the public for entertainment or education.

- Tourist attractions

Places of interest that pull visitors to a destination, open to the public for entertainment or education.

- Tourist:

Someone who travels at least 80 kilometres from his or her home for at least 24 hours, for business or pleasure or other reasons; can be further classified as domestic, inbound, or outbound.

- trade show or trade fair

Allows a range of vendors to showcase their products and services either to other businesses or to consumers. Can be a standalone event or adjoin a convention or conference.

- Trade shows/trade fairs

Can be stand-alone events, or adjoin a convention or conference and allow a range of vendors to showcase their products and services either to other businesses or to consumers.

- Tragedy of the commons

The tendency of society to overconsume natural resources for individual gain.

- tragedy of the commons

The tendency of society to overconsume natural resources for individual gain.

- Transferable skills

Skills required to perform a variety of tasks that can be transferred from one type of job to another.

- transferable skills

Skills required to perform a variety of tasks that can be transferred from one type of job to another.

- Transportation Safety Board (TSB)

The national independent agency that investigates an average of 3,200 transportation safety incidents across the country every year.

- Travel

moving between different locations for leisure and recreation

- travel

Moving between different locations for leisure and recreation.

- Travel agency

A business that provides a physical location for travel planning requirements.

- travel agency

A business that provides a physical location for travel planning requirements.

- travel agent

An individual who helps the potential traveller with trip planning and booking services, often specializing in specific types of travel.

- Travel agent

An individual who helps the potential traveller with trip planning and booking services, often specializing in specific types of travel.

- Travel Industry Regulation

Part of the BC Business Practices and Consumer Protection Act that outlines the requirements for licensing, financial reporting, and the provision of financial security for travel sales.

- Travel services

Under NAICS, businesses and functions that assist with planning and reserving components of the visitor experience.

- travel services

Under NAICS, businesses and functions that assist with planning and reserving components of the visitor experience.

- Trend

A phenomenon that influences things for a long period of time, potentially shifting the focus or direction of industry and society in a completely different direction.

- trend

A phenomenon that influences things for a long period of time, potentially shifting the focus or direction of industry and society in a completely different direction.

- Unintentional torts

Primarily consist of negligence.

- unintentional torts

Primarily consist of negligence.

- United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People (UNDRIP)

a 2007 United Nations statement that set forth the minimum standards for the survival, dignity, and well-being of the indigenous peoples of the world

- United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO)

UN agency responsible for promoting responsible, sustainable, and universally accessible tourism worldwide.

- Upscale casual restaurant

Emerging in the 1970s, a style of restaurant that typically only serves dinner, intended to bridge the gap between fine dining and family/casual restaurants.

- upscale casual restaurant

Emerging in the 1970s, a style of restaurant that typically only serves dinner, intended to bridge the gap between fine dining and family/casual restaurants.

- Values

An individual’s ways of living and making decisions that is congruent with his or her beliefs and principles.

- values

An individual’s ways of living and making decisions that is congruent with his or her beliefs and principles.

- VFR

An acronym for visiting friends and relatives; a tourism consumer market.

- Visitor centre

A building within a community usually placed at the gateway to an area, providing information regarding the region, travel planning tools, and other services including washrooms and Wi-Fi.

- visitor centre

A building within a community usually placed at the gateway to an area, providing information regarding the region, travel planning tools, and other services including washrooms and Wi-Fi.

- Visitor-ready operation

Often a start-up or small operation that might qualify for a listing in a tourism directory but is not ready for more complex promotions (like cooperative marketing); may not have a predictable business cycle or offerings.

- visitor-ready operation

Often a start-up or small operation that might qualify for a listing in a tourism directory but is not ready for more complex promotions (like cooperative marketing); may not have a predictable business cycle or offerings.

- Volunteering

Performing a service without pay in order to obtain work experience, learn new skills, meet people, contribute to community, and contribute to a cause.

- volunteering

Performing a service without pay in order to obtain work experience, learn new skills, meet people, contribute to community, and contribute to a cause.

- Waiver

A document used as risk management technique where the responsibility for the risk is transferred to the participant through contract and voluntary acceptance of risk.

- waiver

A document used as risk management technique where the responsibility for the risk is transferred to the participant through contract and voluntary acceptance of risk.

- Western Canada Mountain Bike Tourism Association (MBTA)

A not-for-profit organization working towards establishing BC, and Western Canada, as the world's foremost mountain bike tourism destination.

- Western Mountain Bike Tourism Association (MBTA)

A not-for-profit organization working towards establishing BC, and Western Canada, as the world's foremost mountain bike tourism destination.

- Wilderness Tourism Association (WTA)

An organization that advocates for over 850 nature-based tourism operators in BC, placing a priority on protecting natural resources for continued enjoyment by visitors and residents alike.

- Wine tourism

Tourism experiences where exploration, consumption, and purchase of wine are key components.

- wine tourism

Tourism experiences where exploration, consumption, and purchase of wine are key components.

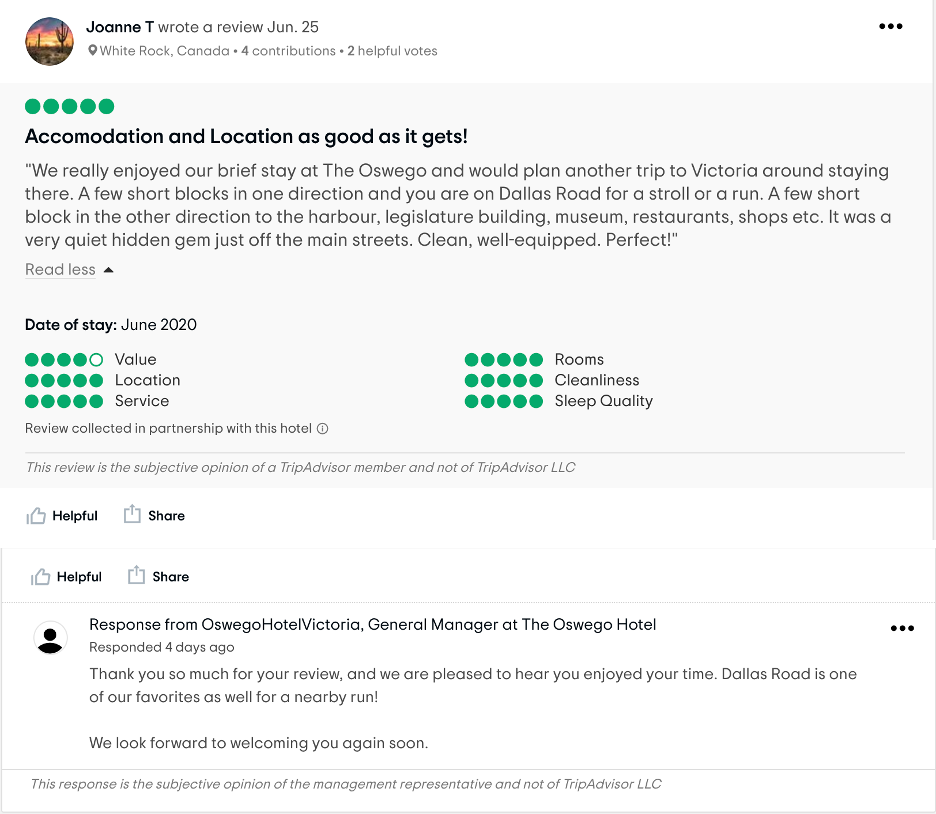

- Word of mouth