The pristine quality of Robert McCausland’s work (1856-1923) solidified the McCausland firm’s reputation in stained glass. After extensive study in England and Europe, Robert returned to Toronto to become the chief designer and in 1881, partner in his father, Joseph’s stained glass studio. After the stained-glass department of the McCausland firm was made a separate company under Robert in 1897, the first commission Robert worked on his own was a large window in Toronto’s third City Hall. The studio rose in prominence and, given the McCauslands’ Anglican faith, became the preferred Canadian stained glass maker for Anglican and occasionally Roman Catholic churches in Ontario. Robert’s connection with leading studios and their designers in England lead numerous highly skilled English-trained artists, members of the prestigious British Society of Master Glass Painters, to work for McCausland.

Five generations of McCauslands have overseen the work of the firm: Joseph (active 1850-1896); Robert (active 1897-1923); Alan (active 1923-1952); Gordon (active 1952-1968); and Andrew (active 1969–present). Many of the artists, like Nathaniel Theodore Lyon and William Meikle, worked for McCausland before venturing into their own successful studios.

Bibliography

“About Us”. Robert McCausland Limited. 2014. https://www.eternalglass.com/.

Aylott, Chris. “Stained Glass Windows Follow History’s Footsteps.” Canadian Churchman (October 1986): 12-13.

Burns, Patrick. “Robert McCausland Limited, Toronto, founded 1857.” Institute for Stained Glass on Canada. https://www.glassincanada.org/news/article-2/.

Keeble, L.Corey & Alice Hamilton. “Robert McCausland Limited Honoured by the City of Toronto.” The Leadline (Fall 1981): 4-5.

Mattie, Joan. The Stained Glass of Robert McCausland Ltd. Ottawa: Canadian Parks Service, 1991.

McCausland, Andrew & Alice Hamilton. “Robert McCausland Ltd. of Toronto.” Stained Glass 80.2 (Summer 1985): 136-139.

McCausland Limited. On the Making of Stained Glass Windows. Toronto: Robert McCausland Limited, 1913.

Spicer, Elizabeth. Trumpeting Our Stained Glass: The Church of St. John the Evangelist, London, Ontario. London: St. John the Evangelist, 2008.

“Stained Glass Windows.” Pages of Weston History. http://omeka.tplcs.ca/omeka_weston/exhibits/show/architecture/stained-glass-windows.

Robert McCausland Limited, Christ Blessing the Children. St. John the Evangelist, London, Ontario, 1932 (Photograph: Anahí González).

Christ Blessing the Children

Artist: Robert McCausland Limited, Toronto, 1932. Releaded October 18, 1980.

Dedication: “To the Glory of God and in Loving Memory of Stephen Grant, 1847 – 1923, and of His Wife Julia Christian, 1846-1932. Erected by Their Children, 1932.”

The diptych windows depict the story of Christ blessing the children from the Gospels, which is connected to the debate concerning whether children should be blessed prior to confirmation within the Christian traditions. According to the story, mothers and fathers present their children to Christ for blessing but his disciples raise objections as shown by Peter and John’s attempts to disperse them from being blessed. Indeed, in the windows, John can be seen making a gesture towards Christ, while Peter recoils a hand to his mouth in disapproval. Christ counters the disciples’ objections with the famous quote from Matthew 19:14, “Suffer little children, and forbid them not, to come unto me: for of such is the Kingdom of Heaven.” The subject was complicated further during the Protestant Reformation. Scenes of the subject were popularized by Lucas Cranach the Elder, a good friend of Martin Luther, as a commentary on the Catholic traditions and as a depiction of the theme of the free dispensation of divine grace, an essential part of Lutheranism.

Robert McCausland Limited, East Window: Christ Blessing the Children. St. John the Evangelist, London, Ontario, 1932 (Photograph: Anahí González).

On the left, three small children with their parents are being presented to Christ to be blessed. On the right, Christ receives the children, as shown by a small child clothed in gold. Typical of McCausland’s style, the background contains trees and other natural elements along with canopies on top of and borders around the window.

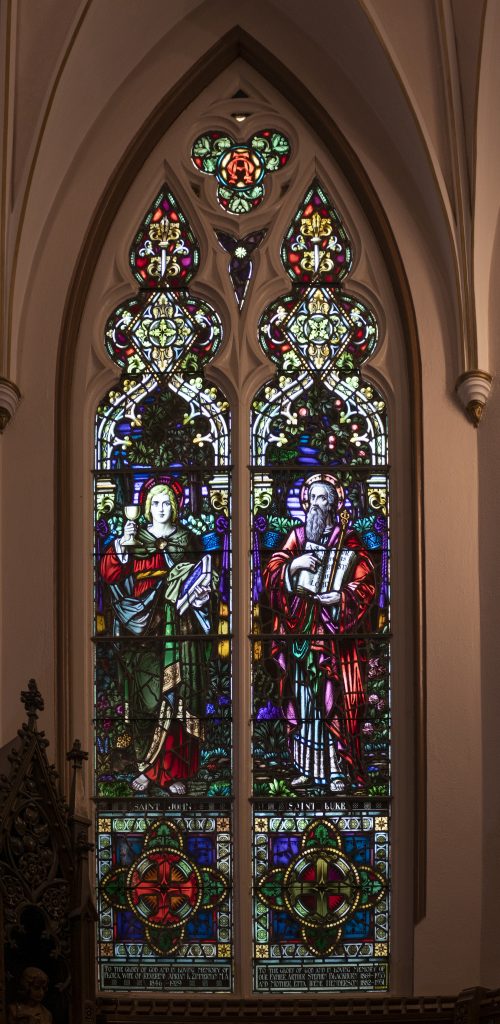

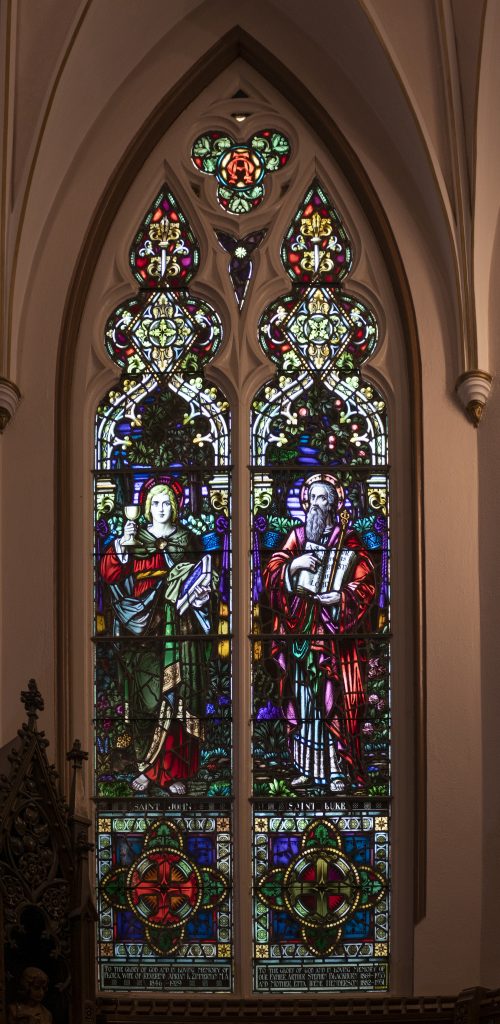

Robert McCausland Limited, St. John the Evangelist and St. Luke. St. John the Evangelist, London, Ontario, 1936 (Photograph: Anahí González).

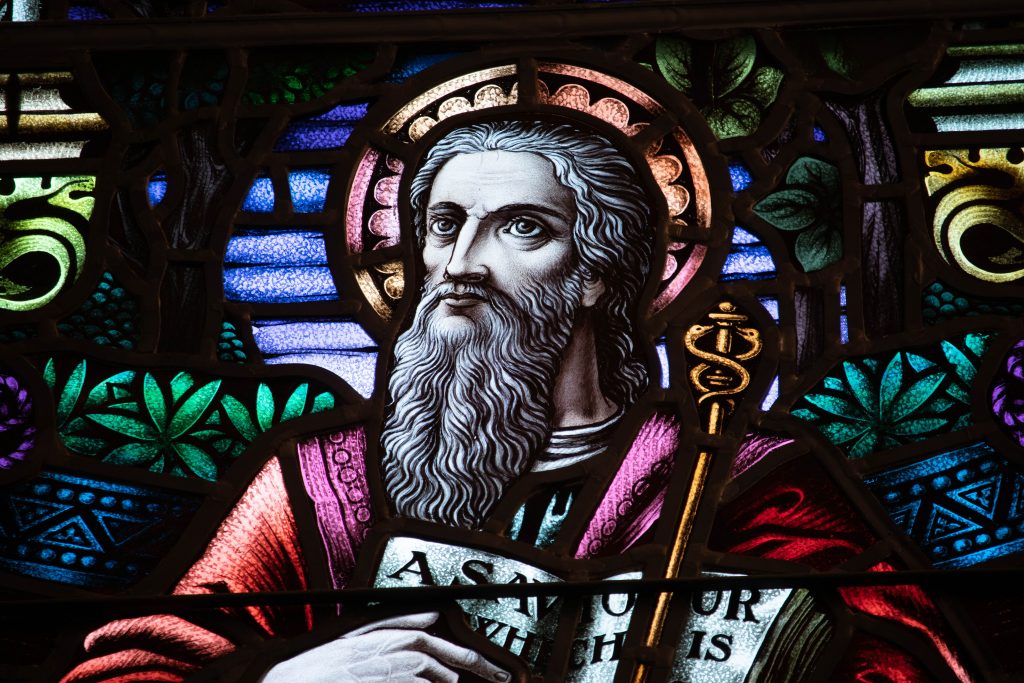

Saint Luke

Robert McCausland Limited, Toronto, 1936

“To the Glory of God and in Loving Memory of Our Father, Arthur Stephen Blackburn, 1869 – 1935 and Mother, Etta Irene Henderson, 1882 – 1931.”

Unveiled: February 28, 1937

Donors: Miriam and Walter Blackburn

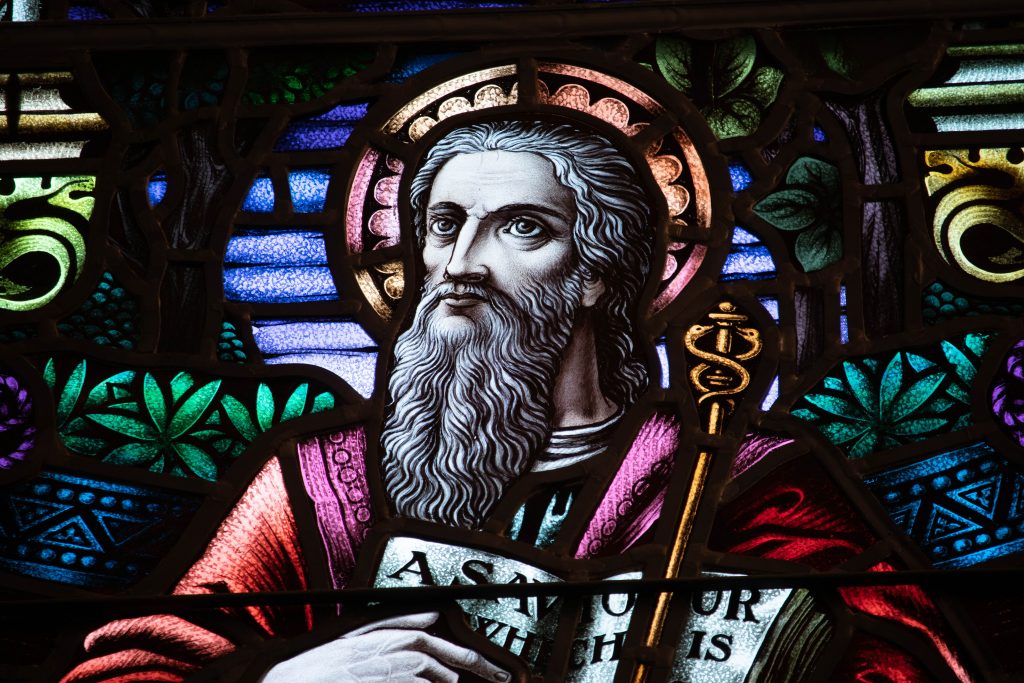

Luke, the author of the Gospel of Luke and the Acts of the Apostles, carries the book of his Gospel in one hand. As the patron saint of artists and physicians, he holds the staff of Aesculapius, the Greek god of healing. Luke was a companion of Paul and mentioned in the letters of Paul as the “beloved physician” (Colossians 4:14). Along with connections with Paul, Luke is also associated with Mary as the important events in her life, like the Annunciation, are described only in his gospel.

Robert McCausland Limited, Detail: St. Luke. St. John the Evangelist, London, Ontario, 1936 (Photograph: Anahí González).

The Blackburn family has a long and dedicated relationship with St. John’s church, to the London Free Press, and to the city itself. Josiah Blackburn launched a daily newspaper on May 15, 1855. [1] In 1900, his son, Arthur Stephen became secretary-treasurer of the business and then president following his brother Walter Josiah’s death in 1920. Arthur Stephen married Etta Irene Henderson of Wardsville married in 1902. Etta was active in a Red Cross committee that set up a clothing supply depot for civic relief in London circa 1918. Their son, Walter Juxon continued the newspaper as the editor for many years and his daughter, Martha Blackburn-Hughes, ran the Blackburn Communications Group until her death in 1992.

[1] As cited in Elizbeth Spicer, Trumpeting Our Stained Glass Windows (London: St. John the Evangelist, 2008), #11.

Robert McCausland Limited, Detail: St. John the Evangelist. St. John the Evangelist, London, Ontario, 1936 (Photograph: Anahí González).

St. John the Evangelist

Robert McCausland Limited, Toronto, 1936

“To the Glory of God and in Loving Memory of Flora, Wife of Reverend Adrian L. Zimmerman, M.A. 1864 – 1929″

Donor: Flora M. Zimmerman

John, who was one of the sons of Zebedee, was called “the disciple whom Jesus loved” six times in the narrative of the Gospel of John. In his left hand, he carries the book of his Gospel. With his other hand, he raises the chalice, in reference to Christ’s words to John in Matthew 20:23: “And he saith unto them, Ye shall drink indeed of my cup, and be baptized with the baptism that I am baptized with; but to sit on my right hand, and on my left, is not mine to give, but it shall be given to them for whom it is prepared of my Father.”

According to Elizabeth Spicer, Flora Zimmerman was a devoted member of the congregation.[1] Her husband, Reverend Adrian L. Zimmerman was an Anglican clergyman and an instructor at Huron College for a brief period. He died on June 7, 1878, at 36, leaving Flora to raise their three children, Flora, Adrian, and Louis Patrick. Her son Louis laid to rest on July 30, 1903, at age 29. She herself died in 1929, and her other son Adrian was buried on June 7, 1933. The last member of the family, Flora M. Zimmerman, had a notable career as a teacher, owner of a school, and later a clerk at Canada Trust. She died June 28, 1940, at age 75.

[1] Elizbeth Spicer, Trumpeting Our Stained Glass Windows (London: St. John the Evangelist, 2008), #12.

Robert McCausland Limited, Detail: St. John the Baptist. St. John the Evangelist, London, Ontario, 1936 (Photograph: Anahí González).

St. John the Baptist

Robert McCausland Limited, Toronto, 1936

Donated by the Congregation

John, the cousin and forerunner of Jesus, is clothed in green to symbolize spring, the triumph of life over death, charity, regeneration of the soul through good deeds and hope. He holds a lamb referencing Christ as the Lamb of God, and a staff with a white banner that symbolizes Christ’s Passion.

As noted, this window was added to The Good Shepherd light created by Joseph McCausland. Added to the larger window in 1936, the central zone was restored and two new panels, depicting the Blessed Virgin Mary and John the Baptist, were installed. The original scheme, design and colourings of the window were not altered. An additional pane of glass was installed on the outside to ensure the preservation of the window.

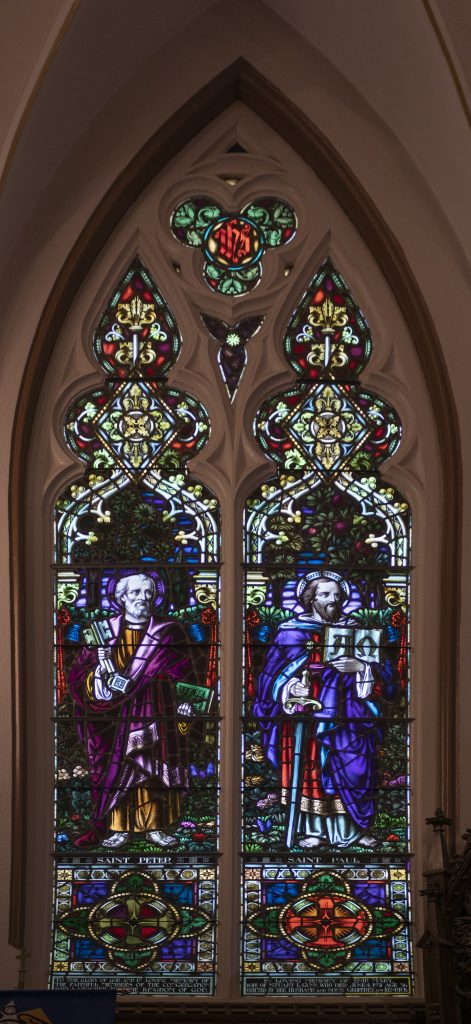

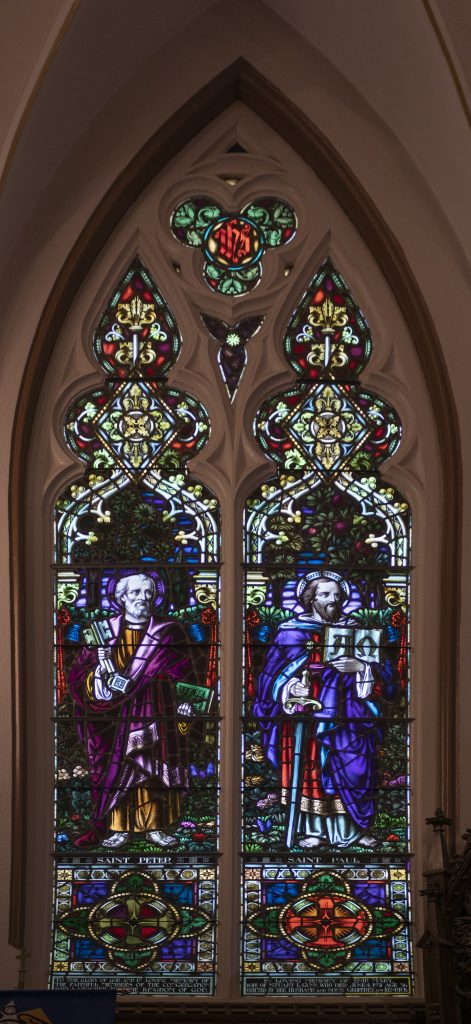

Robert McCausland Limited, St. Peter and St. Paul. St. John the Evangelist, London, Ontario, 1936 (Photograph: Anahí González).

Saint Paul

Robert McCausland Limited, Toronto, 1936

“In Loving Memory of Enid Mary, Wife of Stuart L. Gunn, Who Died June 4, 1931, Age 36. Erected by Her Husband and Sons Geoffery and Kenrick”

One of the most influential figures in Christianity, Paul the Apostle is the patron saint of missionaries, evangelists, writers, and public workers and the author of the principal Epistles of the New Testament. Paul was originally named Saul and was a Roman citizen who presided over the persecutions of the early followers of Christ. Saul famously experienced a powerful vision on the road to Damascus that led to his conversion to Christianity. Upon his baptism, he took the name Paul and then began his famous missions. In the image, Paul holds his symbols, a sword in and an open book with Alpha and Omega on each side.

Robert McCausland Limited, Detail: St. Paul. St. John the Evangelist, London, Ontario, 1936 (Photograph: Anahí González).

Enid Mary (Burton) Gunn was the only daughter of George and Kathryn Burton of Blundlesands, Lancashire, England. According to Spicer, She met Stuart Lowhall Gunn in London, England while serving as a Volunteer Aid Detachment military hospital work and he was a Staff Officer at Canadian Forces Headquarters. [1] They were married as St. James, Piccadilly, in September 1918 and moved to London, Ontario a few months later. Around 1922 the Gunns joined St. John’s, and she became very active in the parish. She was an accomplished musician and had been educated at conservatories in pre-war Berlin. She was also an artist and costume designer for the London Skating Club carnivals. Due to a decline in her health, Enid Gunn returned to England in August 1929 and died in June 1931. Her husband and sons returned to London, Ontario, the following August.

[1] Elizbeth Spicer, Trumpeting Our Stained Glass Windows (London: St. John the Evangelist, 2008), #16.

Robert McCausland Limited, Detail: St. Peter. St. John the Evangelist, London, Ontario, 1936 (Photograph: Anahí González).

Saint Peter

Robert McCausland Limited, Toronto, 1936

“To the Glory of God and in loving memory of the Faithful Members of the Congregation who laboured for the Kingdom of God.”

Donated by the Congregation.

The Apostle of converted Jews, and the patron saint of Fishermen, Peter bears the keys of the Kingdom of Heaven, as promised by Christ (Matthew 16:19). In the image, Peter has the keys of the Kingdom of Heaven in his right hand, while his left hand holds the book of the Gospel.

The window, along with Saint Luke, The Blessed Virgin Mary, and Saint Paul, was installed in new spaces created by the addition of a three-sided apse to the Sanctuary in 1927. At the same time, two panels were added to the Good Shepherd window, representing John the Baptist and the Blessed Virgin Mary.

![Lyon, Petere]](https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/1838/2021/08/28-1024x683.jpg)