Advancing Intercultural Competence for Global Learners

Advancing Intercultural Competence for Global Learners by cmcwebb is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Advancing Intercultural Competence for Global Learners by cmcwebb is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

I

1

Welcome to Advancing Intercultural Competence for Global Learners. This program is divided into three interconnected modules to nurture your intercultural competence more holistically.

The estimated time-to-completion is four hours per module, totalling 12 hours for the entire program.

Mossholder, T. (2019). Group of people taking picture. Pexels. https://www.pexels.com/photo/group-of-people-taking-picture-3063478/

You may choose to complete the modules independently if you want to focus on a specific area of development, although the best learning experience comes from a combination of the three modules. Whatever you choose, we encourage you to engage with the content, take time to reflect on what you are learning, be open to new perspectives, and use the strategies suggested in your everyday interactions.

The three modules follow a student-engagement approach where you involve yourself with the content through self-reflection, interactive activities with automatic feedback, summaries of key points, and strategies to support your intercultural development as a global learner.

In every module, you will find interactive activities, definitions, and questions for reflection. You can also follow the links to the Glossary section at any time to expand your knowledge, review terms, or just to have an overview of the concepts used across the three modules.

In this section, you will explore two key concepts, global learner and intercultural competence (IC), in an interactive way. This will help you gain a better understanding of what the program is focused on and what you can expect when interacting with the content.

It is important to ensure you understand what is meant by a global learner to have a clearer idea of what you are aiming for as you immerse yourself in the intercultural learning process.

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/interculturalcompetence/?p=508#h5p-21

How close was your understanding of global learner to the definition provided? In what way was it similar? How was it different? In what way does being a global learner help you in your personal and professional life?

Although we often hear these two terms used interchangeably, they are, in fact, not the same, as explained below:

Intercultural (e.g., competence, communication, engagement) focuses on a deeper understanding of interactions between cultures and the mutual exchange of ideas from a more holistic and comprehensive perspective.

Cross-cultural (e.g., communication, studies, or interactions) involves comparisons of different cultures around a particular aspect; for example, work values in Switzerland versus Saudi Arabia, or how people greet each other in Canada compared to Spain.

Since our program content is not limited to comparisons across cultures, you will see references to intercultural competence, communication, studies, interactions, engagement, and so on. Your objective is to develop a better understanding of what happens within, around, and beyond interactions, to equip you with ways to learn about different perspectives, to help you develop skills, and overall to support your intercultural learning journey.

Intercultural competence is a complex process—a multi-faceted set of abilities—that influence the way we interact and think, what we do and avoid doing, the decisions we make, and how all of these affect our own group as well as cultural others.

Perhaps you already have a notion of intercultural competence; even if you do not, there are ideas around it that we need to clarify. Let’s start with that!

Examine each statement below and decide whether they are true or false in terms of your own understanding of intercultural competence.

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/interculturalcompetence/?p=508#h5p-22

Intercultural competence development…

Well done!

Now you have a better understanding of what the program is about and what you can expect. Start engaging with the content in the modules and enjoy the journey!

2

II

3

This module focuses on helping you create awareness of your own and others’ cultural selves while introducing strategies to suspend judgement when you perceive people to be different from you. Through the content and interactive exercises, you will engage with real-life examples to understand and appreciate multiple cultural perspectives, as well as to develop the skill of self-reflection, which are important in intercultural interactions.

By the end of this module, you will be able to:

You can refer to the glossary at any time to find definitions of these and other keywords:

Culture, Iceberg Theory, Ethnocentrism, Bias, Stereotype, Microaggression

4

Our very survival has never required greater cooperation and greater understanding among all people from all places than at this moment in history. And when that happens — when people set aside their differences, even for a moment, to work in common effort toward a common goal; when they struggle together, and sacrifice together, and learn from one another — then all things are possible.

United States of America (USA) President Barack Obama (Commencement speech, University of Notre Dame, 2016)

Culture hides much more than it reveals, and strangely enough what it hides, it hides most effectively from its own participants. Years of study have convinced me that the real job is not to understand foreign culture, but to understand our own.

Edward T. Hall, Anthropologist

5

A self-awareness and identity wheel serves as a visual representation of the different parts of an individual’s personal, social, and cultural characteristics; it illustrates the construction of our self-perception and identity. Understanding ourselves by being aware of our identities and perspectives is a steppingstone to understanding how other identities are constructed and how we relate to others.

At the centre of the wheel, you find your unconscious self, comprising who you are as an individual and the elements of your identity that are mostly static and unchangeable. On the outside, you find your conscious development and how you describe yourself based on achievements and what you have gained through studying or working formally and informally. Your geography helps you position yourself in relation to where you live and how you relate to your surroundings. Your choices involve that part of your identity that reflects how you navigate your adult life and the decisions you make along the way. Your perceptions refer to your self-awareness regarding how you believe you are perceived and how you perceive others. Your engagement highlights the way you relate to others around, who is included in your circle of friends, and the extent to which you reach out of your circle of commonality. A part of your identity that combines experiences and challenges is represented as your struggles, which you should learn to recognize to help you understand other people’s pains and troubles. Finally, your goals are part of your identity because they represent what drives you and what you are aiming for, whether at the personal, cultural, or societal level.

The graphic below expands on how these elements of your identity are defined. Click on each one to learn more about them. As you read, think about how you would define your own identity within each element.

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/interculturalcompetence/?p=75#h5p-71

Create your own self-awareness profile to help you build a visual of your own self-awareness and identities. The aim is to help you further understand intersectionality, how we belong to many groups at the same time, and how we relate to our surroundings.

To do this, look at the various categories below and write your own answers to each of the eight sections on a separate paper or on your word processor. Alternatively, print out the Word document My Self-Awareness and Identity Profile and complete the activity there.

Click on each card below to see some prompts to help you think about what to write. Think about this activity as a picture of your current personal, social, and cultural identity. Focus on who you are now and make sure the words or phrases you use reflect your present self, as your holistic self-identity can change over time.

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/interculturalcompetence/?p=75#h5p-32

Explore the following self-awareness and identity profiles from two other people. As you read through them, think about how similar or different your own responses are. Identify ways in which your self-awareness and identity profiles connect based on each of the eight elements listed.

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/interculturalcompetence/?p=75#h5p-34

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/interculturalcompetence/?p=75#h5p-35

People’s identities are multi-layered and complex. Each one of us—even if we are from the same town and went to the same places growing up—will have different experiences, outlooks, and goals. When meeting someone you perceive to be different, it is unfair to rely on the way you think they are without having had the opportunity to engage and connect with them. You would be surprised by how many ways our multi-layered identities can connect. In addition, even if you feel you cannot connect with someone due to what you consider right or wrong, there is much more to a person than you could ever imagine. Perhaps talking about your differences can help you appreciate how others think. You do not need to become someone else to understand people, and you do not need to agree with them to gain a better understanding of how others perceive themselves and their identities. Moreover, it is key to remember that if you only connect with those who are similar to you, you will not learn about the world, what is out there, who people really are, and the changes needed in society.

Reach out to someone from a different cultural group—perhaps an acquaintance or someone new from the university or your workplace. Strike up a conversation and come from a place of curiosity, learn about the other person and be ready to share about your own identity, whatever feels comfortable. This will help you find commonalities where you perhaps saw mostly differences.

6

Culture is a very complex term; there is no single definition that encompasses everything that culture is because it spans every aspect of our lives as social beings. We may hear terms such as organizational culture, team culture, and material culture, and we refer to ancient cultures or the fine arts as culture. However, what does it mean when we talk about belonging to a culture or several cultures? How does this allow us to distinguish cultures around the globe?

Take a moment to think about what culture means to you. What do you understand by culture?

If someone asks you to explain what you mean by culture, what would you say?

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/interculturalcompetence/?p=89#h5p-1

For our purposes, we will understand culture as

“An accumulated pattern of values, beliefs, and behaviours, shared by an identifiable group of people with a common history and verbal and nonverbal symbol systems”

What examples of culture that you listed are included in this definition? Is there something you did not consider?

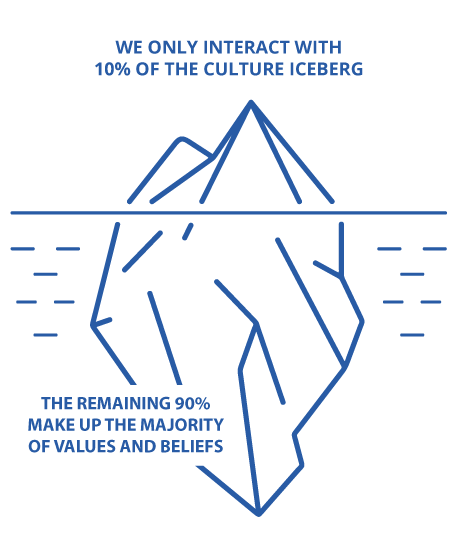

Anthropologist Edward T. Hall (1976) used a visual representation of an iceberg to create a better understanding of culture and its components. Hall explains that, at the top of the iceberg, there are cultural elements one can perceive with the senses. They are learned or acquired consciously, they can change relatively easily, they can be observed, they are tangible, and one may be able to describe them without having extensive experience in another culture. Conversely, at the bottom of the iceberg, there are elements one cannot perceive with the senses. They are learned or acquired unconsciously, they are hard to change, they are intangible, and one cannot describe and understand them without having extensive experience in another culture.

Watch the video “Cultural Iceberg” (1’51”) that explains Hall’s theory. As you watch, try to think about more examples you would incorporate at the top and bottom of the iceberg.

When we first interact with people from a different cultural background (at home and abroad), we are only interacting with the top 10% of the culture iceberg. That is the tip of the iceberg.

Iceberg by Oleksandr Panasovskyi from NounProject.com and licensed under CC BY 3.0. Colours changed and labels added.

It is common to make assumptions or develop ideas about other cultural groups without really understanding their internal or deep culture. That is, the remaining 90% that makes up the majority of our values and beliefs.

Look at the words listed below. Each one represents an element of culture. Decide whether they could be expected to be either at the top or bottom of the iceberg based on the descriptions below.

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/interculturalcompetence/?p=89#h5p-2

Hall’s Culture Iceberg shows how elements on the surface are visible, palpable, and easier to adapt to or learn. As examples, consider how you have expanded your appreciation of music in a different language or dialect, how you have incorporated foods from other cultures into your regular meals, or how you have read literary works from writers around the globe. This is considerably easy to do while making conscious decisions to observe, try, or participate in a different cultural experience.

However, what happens with the elements at the bottom of the iceberg? As we grow up, we internalize our culture’s way of thinking and being. In addition, we internalize our culture’s values, ways of behaving, attitudes, philosophical concepts, approaches to work and study, ways to understand and forge relationships, family dynamics, how to show respect, and so on. It is here, at the core of our cultural background, that most intercultural misunderstandings take place because we cannot see and understand these elements when we first meet each other.

Only through exposure and openness to cultural learning can we create meaning and understand how these elements are similar or different to our core culture’s ways of thinking, reasoning, behaving, and even feeling, which define what is considered right and wrong within each cultural group.

Think about a time when you travelled somewhere and met someone from another culture:

Retrieved from https://thenounproject.com/search/?q=iceberg&i=2258187 and licensed under CC BY 3.0. Colours changed and labels added.

7

From childhood, we are socialized into our culture and learn about what constitutes right or wrong. At the same time, we are constantly surrounded by outlooks and teachings from our family or school and are exposed to images and content from films, news, the internet, opinions we hear from other people, and so on. These sources constantly influence us and shape the attitudes we have toward ourselves and others.

Before engaging in the activity below, take a moment to think about how you feel toward difference; this could be about doing things in a different way, having a different opinion, or having a cultural background different from yours. How open are you to living in a diverse neighbourhood? How comfortable do you feel learning about doing things differently or seeing things from a different perspective?

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/interculturalcompetence/?p=95#h5p-4

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/interculturalcompetence/?p=95#h5p-23

Look at the statements that seem more acceptable to you, why do you think that is? What about those you marked as unacceptable? What bothers you about them? Below, you will learn about the messages statements such as these may convey.

At some point in our lives, each one of us holds ethnocentric attitudes because we rely on what we know to be right based on our upbringing—what we learned as we were growing up. We can clearly see this when we observe or interact with people from other cultures and we start forming ideas about what they do right or wrong.

Ethnocentrism is the belief that one’s culture is better or superior to others, that the way we do things is right, and the way others do things, act, or behave is wrong. It is a very limiting view that leads people to make unfair assumptions about other cultural groups and impedes the appreciation of different ways of being and behaving.

The statements in the activity above show different degrees of ethnocentrism. In some, a simple change in phrasing would make a big difference. For example, instead of saying, “Hebrew and Arabic are written backwards,” it would be better to say, “Hebrew and Arabic are written from right to left.” This is a more accurate way of describing what you see that removes hidden criticism: “If it’s not written the way I do it (in English, for example), it is backwards.” Remember that for someone who grew up writing from right to left, that is the normal and correct way to write, and, from that view, perhaps English seems to be written backwards.

Taking another example from the activity, if someone says, “Nepalese food is gross,” it is quite unfair to people who grew up with it and enjoyed eating it. By the same token, the food you eat could be really strange to some people. Therefore, it would be better to say, “Nepalese food is very different from what I am used to,” which is a fair statement. Other statements in the activity are politically charged or express views that require a shift in thinking; these would take more time to inspire change. It is important to start by realizing how the way we say things can indeed be unfair or inaccurate and convey an ethnocentric tone—this should help you work toward changing an ethnocentric attitude.

Ethnocentric attitudes can hide behind expectations about others and comments in everyday conversations, as well as in advertising, curriculum content at school and university, policies, and even laws. To see this in context, watch this advertisement of Cadillac coupe 2014 and answer the three questions that follow.

Watch the 2014 Cadillac ELR TV Commercial, ‘Poolside’ (0’56”), a commercial from Cadillac.

Write your answer in the space provided.

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/interculturalcompetence/?p=95#h5p-5

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/interculturalcompetence/?p=95#h5p-6

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/interculturalcompetence/?p=95#h5p-7

8

How would you describe people from Italy, Japan, or Mexico? What about Indigenous people from Canada or from another country? What attitudes and behaviours come to mind when you think about a Black person? What stereotypes do people have about your own cultural group? There is no shortage of stereotypes about cultural groups; they have managed to filter into our everyday lives. We may not see or be quite conscious about stereotypes, but they are always around us. One of the challenges about eliminating stereotypes is that they are very easy to perpetuate through unfair comments, jokes, inaccurate advertisements, media, and so on. Stereotypes can support a vicious circle of false beliefs directed at different cultural groups while creating a social stigma among those very groups. For this reason, we must understand them; to deconstruct stereotypes, we need to face them.

Think about the associations you make in terms of cultural attributes, icons, values, or behaviours for the following people. What stereotypes can you identify for each one of them?

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/interculturalcompetence/?p=100#h5p-30

Looking back at the stereotypes you identified, consider the following questions:

Unless you have travelled extensively, immersed yourself in another culture, have a continuous relationship with people from other countries, or have taken time to study other cultures, it is likely that what you know about other people comes from external influences: Something you watched in a film, repeated iconography added to advertisements, products, or displayed in shops, or they could originate from something you heard from a relative at the dinner table, from a friend’s comments, or even based on a single event you experienced.

When we have limited awareness or knowledge of other cultures, we tend to rely on stereotypes as sources of information. By doing this, we perpetuate ideas of groups that do not reflect reality.

Stereotypes are overgeneralizations of perceived behaviours applied to an entire group based on limited observations and an oversimplification of ideas.

Some stereotypes may seem positive. For example, “Black people are great athletes, Latin Americans are great dancers, Japanese women are hard-working,” but they are still overgeneralizations of potential attributes associated with a group. One of the problems this creates is that when we meet someone from that group, we expect them to be like their stereotype and feel disappointed when they are not.

It is important to consider that within each cultural or national context, racial stereotypes tend to favour and highlight the positive and desirable attributes of the dominant race or group (e.g., White Canadians) while devaluing or limiting the appreciation of minority groups (e.g., Black Canadians, Indigenous peoples, Southeast Asians, and so on). Stereotypes can and often lead to unfair treatment of people because of the assumptions and attitudes they produce. Stereotypes may become prejudice, which further becomes actions that contribute to discrimination.

Prejudice is a preconceived opinion of a group that is not based on reason or derived from experience through interactions. It means having negative opinions of others without sufficient knowledge. Prejudice results from constantly relying on unfair representations of a group and lead to hatred or discrimination.

Discrimination is an unjust action or unfair treatment of a person or a group on the grounds of their identity. For instance, based on race, sex, ability, or origin.

Constantly relying on unfair representations of a group affects the way we interact with and judge other people. This can work on an unconscious level, but can also turn into policy, where unjust practices can hide. In addition, stereotypes are damaging to people because they can put pressure on members of culturally diverse groups to be more like members of the dominant group.

Watch this TED Talk by Canwen Xu, “I’m not your Asian stereotype” (9’38”) and pay attention to the examples she provides and her discussion on conforming to or confronting the dominant group. Keep in mind that, although her example addresses a Chinese-American identity, her story reflects the experience of people across many countries. As you watch, think about your own experience and pressures around you and how this may reflect the experience of people you know that perhaps you have not considered before.

To follow up, think about the following questions and enter your answer in the space provided.

Based on Canwen Xu’s talk…

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/interculturalcompetence/?p=100#h5p-9

Canwen Xu’s talk makes reference to the American melting pot, an idea embraced in the United States in the 20th century that continues to be supported by many, where cultural differences “melt down” to create a single, strong national identity. The expectation is that people who are different should assimilate into the culture and be more like the mainstream American. The problem with this is that it assumes that assimilating into the American culture is the most a person can aspire to while diluting or suppressing one’s cultural background. The pressure to conform is present across all levels and contexts where, in order to succeed, people must try to be more like the dominant White majority.

In comparison, in the Canadian context, the idea of multiculturalism was also borne in the 20th century and emerged as an object of national conversation. However, instead of supporting the cultural assimilationist views of the United States, it encouraged the appreciation of individual cultures, thus fostering ethnic diversity. This perspective intends to foster better understanding and respect across cultures by appreciating differences instead of expecting assimilation, creating a nation of proud Canadians that are free to speak their language and practice their culture. Still, the Canadian dream of multiculturalism has a long way to go until equity and respect across cultures are fully enacted in everyday life.

Think about your own situation and experience:

9

Tankilevitch, P. (2020). Sandwich Slice with Creamy Peanut Butter Spread. Pexels. https://www.pexels.com/photo/bread-food-sandwich-toast-5419208/

Throughout our lives, we are constantly influenced by people (e.g., friends, family, peers, teachers, co-workers), traditional media (e.g., films, news, TV shows), social media (e.g., Twitter, TikTok, Facebook, Instagram), and single/multiple experiences of our own. Our brains are constantly absorbing all the information around us and categorizing it, creating associations that we automatically rely on. For example, when many people in North America hear “peanut butter and…” the immediate association is “jam,” as this has been part of their background.

In a similar way, our brain creates associations of people and actions or descriptions based on the input around us. This is how this annoying wiring of our brains stores links about all the information we process. Any links we create between people from different backgrounds based on what we hear, read, or see in relation to, for instance, a White woman, an Indigenous person, a South African national, a Scandinavian man, or a Vietnamese grandmother are then translated into biases, affecting the way we act, react, and the attitudes we develop toward other people.

Bias is an unsupported judgement—an automatic association in our brain that demonstrates underlying attitudes in favour or against other people. It happens outside our conscious awareness and affects how we relate to and react to others.

In other words, we all have biases, but most of the time, we are not aware of them. Taking time to understand the bias we hold about other people—those immediate associations our brain makes when we see, think about, or meet cultural others—can help us change our attitudes and what influences our decisions. The key is to be aware of what they are and to avoid relying on them. Remember: You cannot control your bias, but you can control your reaction.

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/interculturalcompetence/?p=104#h5p-10

In their talk, Myers mentions the Implicit Association Test (IAT).

Stereotypes and bias can have a deep impact on racialized groups because they perpetuate an inaccurate representation of a group without taking into consideration the individual, the context, and their experience. Ignoring the need to understand cultural others while relying on bias and stereotypes can have a detrimental effect on society because bias and stereotypes can, in fact, lead to discrimination. How does this happen?

It starts with an inaccurate belief: an imprecise idea of a group based on a single observation (stereotype). Once this belief is in our minds, our brain will create associations based on that observation (bias), which in turn will come into our minds when we see or hear about someone from a given cultural group. At this point, an idea has lodged into our minds that will affect how we perceive another group, how we relate to them, and the potential decisions we may make that can affect that group.

If stereotypes and bias are not challenged, we will continue to be prejudiced towards others, and that prejudice will ultimately continue to benefit some members of the society (the dominant group) while stigmatizing others. What follows is a series of actions that are based on prejudice. That is, discrimination based on race, place of origin, accent (or other factors) that impede advancement, promotion, access, and equal treatment. In other words, those actions become obstacles to achieve equity. What starts with an inaccurate idea or belief turns into an attitude or behaviour, resulting in actions referred to as discrimination.

What can you do? Be intentional about deconstructing stereotypes and avoid relying on them. Check your own biases, do not let them guide your actions, and take time to make relations with people from other cultural groups. This will help you gain an understanding of their perspectives and have a more accurate idea of their cultural makeup and experiences.

Have you ever been a victim of discrimination?

Can you think of examples in past or recent events where a person or group was discriminated against based on stereotypes, bias, preconceptions, or prejudice?

Keep that example of a situation in mind and use the following questions to guide your reflection.

For the situation you’ve identified, reflect on these questions:

Try these strategies based on the three suggestions in Vera Myers’ TED talk:

10

Beyond ethnocentrism, stereotypes, and biases, we often hear, say, and do things that may carry a negative or derogatory meaning and are therefore understood as microaggressions.

Through their research, psychologists Derald W. Sue and Lisa Spanierman (2020) developed a list of categories describing microaggressions that can help us understand how they appear in our interactions. As you read the summary below, think of other examples that may apply to each category.

The effect of microaggressions is real, and psychologists have compared them to “death by a thousand cuts” because these everyday slights indeed affect the victim’s mental health and create a toxic environment at school, work, and even within our personal circles. Another problem with microaggressions is that, if left unchecked, they can be normalized, and the types of offences and actions can become more severe.

Use the descriptions for the categories of microaggressions listed above and then look at the examples listed below. Decide to which category each set of microaggressions belongs.

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/interculturalcompetence/?p=108#h5p-11

After completing the activity, go back and read the examples of microaggressions.

Consider this situation:

You are working on a class project with a group of peers. Everyone is from the same racial background and country except for you. After meeting together to pool all your work, one of your peers says, “Wow, you actually understood the concepts and got the work done. I’m impressed; I didn’t expect that.” The microaggression behind this interaction suggests your peer did not think of you as capable of doing the work or having a clear understanding of the ideas involved. How would you react? You have three options:

Consider the following situations. Explain what is wrong with each one and describe what you would do or say in each case:

Your Japanese roommate, Keiko, invites a (White) friend over for dinner. During the conversation, the guest asks Keiko, “Can I borrow your kimono for Halloween?”

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/interculturalcompetence/?p=108#h5p-28

A French-Canadian woman is in front of you in line at a store. She is trying to pay, but the cashier has a hard time understanding what the woman is asking. After the transaction is complete and it’s your turn to pay, the cashier says to you, “They should get rid of their accent.”

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/interculturalcompetence/?p=108#h5p-31

In the situations above, you witnessed some examples of microaggressions. What are some strategies you might use to deal with them? Review the suggestions below for ideas:

Jordan, B. (2020). Say Sorry. Unsplash. https://unsplash.com/photos/joYk8q_An0o

If you realize you have said or done something that could have made someone uncomfortable, or you unwillingly offended someone, make sure not to let it slide. Own up to it and recognize your misstep. Things may happen at a conscious or unconscious level, but you must take steps to understand what happened and apologize; this allows you to practice understanding, grow emotionally, develop empathy, and help you become more interculturally aware.

If you realize you committed a microaggression or someone else points it out, the first thing you may feel is shock, followed by defensiveness or perhaps superficial remorse. If you find yourself in this situation, these are five steps you can take to address it:

11

This module focused on helping you create awareness for others’ and your own cultural self while introducing strategies to suspend judgement when you perceive people to be different from you. Through content and interactive exercises, you engaged with real-life examples that encouraged you to understand, and appreciate multiple cultural perspectives, as well as develop the skill of self-reflection, which are all important for intercultural competence development.

The following self-assessment will help you synthesize your understanding of concepts around awareness, perceptions, attitudes, the importance of developing intercultural awareness, strategies to deal with bias, stereotypes and microaggressions, and different ways of dealing with challenging intercultural situations. As you prepare to do this self-assessment, keep the following in mind:

Read the following statements and select the concept they are describing [7 points].

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/interculturalcompetence/?p=116#h5p-14

Answer the following questions based on your understanding [15 points].

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/interculturalcompetence/?p=116#h5p-15

Decide whether the following statements are True or False [10 points].

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/interculturalcompetence/?p=116#h5p-16

How would you change the following questions or statements to make them more appropriate? [10 points].

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/interculturalcompetence/?p=116#h5p-29

Read the following situations and identify the issue with the question, statement or attitude. Then, describe the strategy you would use to deal with the situation [18 points].

1. You and your partner, both professionals, just moved to the country and rented an apartment in the centre of the city. The landlord comes around to give you another set of keys, and he asks jokingly, referring to both of you, “Am I going to be harbouring illegal aliens?”

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/interculturalcompetence/?p=116#h5p-18

2. You and a group of friends go out for dinner and have a good time together. Everyone is enjoying themselves. Amidst the conversation, one of your White friends says to your Black friend, “You are not like other Black people.”

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/interculturalcompetence/?p=116#h5p-19

3. An Inuk student in your class is talking to you and a fellow classmate about their experience at the mall where shop clerks kept following them around while browsing. Your classmate says, “I’m sure you imagined it, I’ve never seen that happening.”

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/interculturalcompetence/?p=116#h5p-20

World by Balyanbinmalkan from thenounproject.com and licensed under CC BY 3.0.

World Delivery by DailyPM from thenounproject.com and licensed under CC BY 3.0.

Name Tag by Icon Lauk from thenounproject.com and licensed under CC BY 3.0.

Pointing by Magicon from thenounproject.com and licensed under CC BY 3.0.

Food by Kiran Shastry from thenounproject.com and licensed under CC BY 3.0.

12

Jasper, S. (2018, January 12). H&M—blatant racism or a crass lack of (inter)cultural competence? A Pond Apart. https://apondapart.com/intercultural-competence

Nadal K. L. (2014). A guide to responding to microaggressions. CUNY FORUM, 2(1), 71-76. Retrieved from https://archive.advancingjustice-la.org/sites/default/files/ELAMICRO%20A_Guide_to_Responding_to_Microaggressions.pdf

TEDx Talks. (2019, May 13). It’s time to re-imagine Canada’s ‘nice’ identity | Riley Yesno | TEDxUofT [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dZih64Z2wxQ

Wisconsin Technical College System [WTCSystem]. (2020, May 26). Responding to microaggressions [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HrCgBLoMxTQ

III

13

This module is focused on helping you deepen your knowledge and understanding of culture and how it influences interactions between people from the same or different cultures. You will explore values as indicators of cultural tendencies, gain an understanding of how cultural orientations are used to explain general tendencies across cultures, and you will learn about the role of nonverbal communication in intercultural contexts. This module encourages you to develop a global perspective while identifying ways to expand your knowledge about other cultures through engagement, relatability, and intentionality.

By the end of this module, you will be able to:

You can refer to the glossary at any time to find definitions of these and other keywords:

Cultural universals, Intercultural knowledge, Cultural values, Cultural orientations, Nonverbal communication

14

ka-kí-kiskéyihtétan óma, namoya kinwés maka aciyowés pohko óma óta ka-hayayak wasétam askihk, ékwa ka-kakwéy miskétan kiskéyihtamowin, iyinísiwin, kistéyitowin, mina nánisitotatowin kakiya ayisiniwak, ékosi óma kakiya ka-wahkotowak.

Realize that we as human beings have been put on this earth for only a short time and that we must use this time to gain wisdom, knowledge, respect, and the understanding for all human beings, since we are all related.

Cree (First Nations) Proverb

There’s no such thing as a model or ideal Canadian. What could be more absurd than the concept of an “all Canadian” boy or girl? A society which emphasizes uniformity is one which creates intolerance and hate […] What the world should be seeking, and what in Canada we must continue to cherish, are not concepts of uniformity, but human values: compassion, love, and understanding.

Pierre Trudeau, 15th Prime Minister of Canada

It is not our differences that divide us. It is our inability to recognize, accept, and celebrate those differences.

Audre Lorde, American writer

15

Intercultural competence involves awareness of self and other cultures, knowledge of cultures beyond surface elements (e.g., music, dance, language, food, or traditions), the ability to change perspectives and attitudes, the capacity to identify unjust actions and behaviours, the intentionality to learn from experience and about other people’s experiences, and the development of skills to help individuals adapt to situations and be more effective and respectful when interacting across cultures.

One may hear people affirm they are already culturally competent, that they have intercultural experience, and that they are interculturally successful, but intercultural competence is not about attaining a level, a mark, or passing a test that shows you are ready for intercultural interactions. Rather, it is a lifelong process wherein you continue to have opportunities to gain knowledge and develop skills and embrace the opportunities you have for immersing yourself in different cultural contexts at home and abroad.

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/interculturalcompetence/?p=639#h5p-36

2. Take a closer look at the statements and consider how they may reflect your own experience. As you read the feedback provided on the back of each card, consider how each of these experiences or perspectives could be better used to expand your intercultural knowledge or what you could do now to help you appreciate other people’s perspectives. [Statements 1-7 are from C. Lantz-Deaton and I. Golubeva (2020), pp. 11-17.]

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/interculturalcompetence/?p=639#h5p-37

Karpovich, V. (2021). A Man Listening on His Headphones while Packing His Clothes. Pexels. https://www.pexels.com/photo/a-man-listening-on-his-headphones-while-packing-his-clothes-7365337/

Rossi, G. (2019). White and Black Sailing Ship Print Ceramic Plate. Pexels. https://www.pexels.com/photo/white-and-black-sailing-ship-print-ceramic-plate-1815385/

Kobruseva, O. (2020). Keurig Hot Cafe Escapes Cafe Caramel Box. Pexels. https://www.pexels.com/photo/keurig-hot-cafe-escapes-cafe-caramel-box-5408920/

Suhorucov, A. (2021). Diverse women stacking hands on wooden table. Pexels. https://www.pexels.com/photo/diverse-women-stacking-hands-on-wooden-table-6457563/

Shvets, A. (2020) Women in White Dress Shirt. Pexels. https://www.pexels.com/photo/women-in-white-dress-shirt-4672299/

Shvets, A. (2020) Women With Arms Raised and Holding Hands. Pexels. https://www.pexels.com/photo/women-with-arms-raised-and-holding-hands-4557817/

Wilcox, K. (2018). Four Men Sitting on Platform. Pexels. https://www.pexels.com/photo/four-men-sitting-on-platform-923657/

Burrows, M. (2021). Crop student writing in agenda at desk with laptop. Pexels. https://www.pexels.com/photo/crop-student-writing-in-agenda-at-desk-with-laptop-7129007/

McBee, D. (2018). High Angle Shot of Suburban Neighborhood. Pexels. https://www.pexels.com/photo/high-angle-shot-of-suburban-neighborhood-1546168/

Shvets, A. (2020) Woman Wearing Face Mask at Airport. Pexels. https://www.pexels.com/photo/woman-wearing-face-mask-at-airport-3943883/

16

Expanding intercultural knowledge involves learning more in depth about other cultures to understand, for example, how people think, what is important to them, why they behave in a certain way given a certain situation, and what efficient communication looks like.

There are different ways to expand intercultural knowledge that include awareness of your own culture (e.g., your attitudes, values, expectations, and behaviours), learning about other cultures (e.g., traditions, values, ways of being, and perspectives on an issue), sociolinguistic knowledge (e.g., how culture influences language and communication styles), and having a better grasp of global and local contexts (e.g., politics, history, economics, what is happening in other places, and how an issue is addressed).

How much do you know about other cultures around the globe? Take the short quiz, Test your knowledge of cultures around the world! to help you think about types of intercultural knowledge. Each of the prompts in the quiz refers to a general observation or tendency: something that is commonly done in a country with possible exceptions. Make sure to carefully read the feedback provided for each question. If you make mistakes, you can go back and try again!

17

What elements are common across all cultures? What are things that everybody needs or does regardless of their background? Independently of our background, there are everyday activities, values, and cultural expressions that are present across cultures. We all share commonalities, known as cultural universals; the differences emerge in how we express them. In other words, when they become culture-specific.

To understand the difference between a cultural universal and a culture-specific activity, consider this example discussing the family unit:

“Every human society recognizes a family structure that regulates sexual reproduction and the care of children. Even so, how that family unit is defined and how it functions vary. In many Asian cultures, for example, family members from all generations commonly live together in one household. In these cultures, young adults will continue to live in the extended household family structure until they marry and join their spouse’s household, or they may remain and raise their nuclear family within the extended family’s homestead. In many Western countries, by contrast, individuals are [generally] expected to leave home and live independently for a period before forming a family unit consisting of parents and their offspring.”

Little, 2014, pg. 82

Learning to distinguish between a cultural universal (e.g., family structure and sexual reproduction) and socio-cultural characteristics associated with a group or subgroup (e.g., nuclear vs extended families, same sex or different sex parents) will help you gain a better idea of how behaviours, values, and knowledge are defined within a given culture and across cultures.

Look at the items in the following list and classify the elements into cultural universals (elements present in all cultures) or culture-specific attributes (behaviours specific to certain cultures):

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/interculturalcompetence/?p=658#h5p-38

To expand your knowledge of human activities and traits present around the world, explore the following list of cultural universals. As you read, it may be useful to think about how any of these examples may be expressed in different cultures based on your own cultural background and what you know about other cultural groups. For example, in mainstream North American cultures, wearing black is common during funeral rites, whereas in some Eastern countries, the colour associated with these rites is white.

18

We start learning values from childhood and, as we grow into adulthood, values continue to pervade our lives and create meaning in different contexts. For example, as children, we may learn to respect our parents. As teenagers, we learn rules about what is appropriate when interacting with friends. Then, as adults, we learn about levels of formality and expectations from us as employees.

We constantly see what is around us (e.g., events, behaviours, attitudes, actions, reactions, and values) through our own cultural lenses; this is what makes sense for us. However, when we notice a different way of doing things outside of what we know to be correct, we often interpret the behaviour as wrong, inappropriate, or offensive. If we take the time to “change” our cultural lenses and view things from the perspective of other people or groups, we will realize that they are also following the rules of what is considered right through their own cultural lenses.

Tsukata, R. (2020). Trendy Sunglasses Placed on Wooden Table. Pexels. https://www.pexels.com/photo/trendy-sunglasses-placed-on-wooden-table-5472304/

As we interact with people, we have opportunities to expand our knowledge and gain an understanding of others’ outlooks and ways of being. We can then use what we have learned to try to see things through other people’s cultural perspectives. It is important to remember that the different lenses you use are not limited to people from a different culture, this is also applicable to understand values, history, and experiences of people around you, including second generation immigrants, Indigenous groups, racialized individuals, as well as Black, White, Asian people, and so on. In addition, we make further adjustments to our lenses when we consider the intersectionality of our identities, including socioeconomic background, education, gender, and sexual orientation, among others, where we belong to different subgroups that make up who we are as individuals. Being able to change our perspectives across intercultural and intersectional lines allows us to develop a better understanding of perspectives from our own and other people’s standpoints, further paving the way to gain knowledge about complex issues.

Sees, E. (2019). Round Mirror. Pexels. https://www.pexels.com/photo/round-mirror-2853432/

Watch the TED talk by Julien S. Bourrelle: Learn a new culture (13’19”). Bourrelle is a Canadian engineer who learned to adjust his cultural lenses as he interacted with people in the countries where he lived. As you watch, think about your own experiences in situations where you did not understand what happened—where people reacted in a way you did not expect—and how you can adapt your own perspective to gain knowledge while engaging more successfully with others. You are encouraged to take notes you can later refer to, or simply focus on listening to the speaker while thinking about how the content applies to you.

Based on Bourrelle’s talk, select the best answer to the question:

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/interculturalcompetence/?p=667#h5p-39

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/interculturalcompetence/?p=667#h5p-40

Values are complex and differ from one culture to another within groups, organizations, universities, towns, neighbourhoods, and so on. At any one time, we follow several sets of values that reflect who we are as cultural beings and as members of a society. In addition, people also hold a set of personal values that drive their thinking and way of being. It is important to distinguish between cultural values, based on group tendencies, and personal values, based on what is important to you and what drives or influences your decisions.

Are you aware of your value orientations? Read the following statements and reflect on your own upbringing and what you learned from, for example, your parents, grandparents, and teachers. Which of the options better reflects what you were taught as you were growing up? Note that there are no right or wrong answers; this activity is intended to help you reflect on your values and what is important to you before you seek to better understand other people’s value orientations.

[Adapted from Stringer, D., & Cassiday, P. (2003). 52 activities for exploring values differences. Intercultural Press. pp. 35-36, 43.]

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/interculturalcompetence/?p=667#h5p-41

The values by which we live are not limited to what we learned as part of our cultural socialization. They also include organizational (e.g., university or workplace) and personal values. Although culture is the driving factor for our behaviours, remember that personality, experiences, and the context of situations also play an important role in our interactions and ways of being.

19

Raymond, N. (2013). Nunavut Grunge Flag. Flickr. https://www.flickr.com/photos/80497449@N04/7384683500 licensed under CC BY 3.0.

How much do you know about the Inuit people of Canada? Where do they live? What is their history? What is important for them in life? What are their struggles and challenges? Where have you learned about them? NOTE: Inuit means people and refers to the whole group, the community; Inuk refers to a single person; Inuktitut is the language of the Inuit.

Visit the Indigenous Peoples Atlas of Canada and spend about 5-7 minutes (or more if you wish) browsing through the site to learn more about the Inuit of Canada.

Noahedits. (2020). Inuit languages and dialects. Wikimedia. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Inuit_languages_and_dialects.svg licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

Next, visit “The Inuit Way: A Guide to Inuit Culture” [a pdf which opens in a new window] produced by Pauktuutit Inuit Women of Canada (2006) to introduce and help readers understand the cultural foundations of the modern Inuit. Take this opportunity to learn about the Inuit people. Spend about 5 minutes browsing through the pages. As you do this, think about the following:

GRID-Arendal. (2013). Inuit woman carrying her child, Clyde River, Nunavut Canada. Flickr. https://www.flickr.com/photos/gridarendal/31247360974 licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Read the section on “Traditional Inuit values” on pages 31-40 of “The Inuit Way: A Guide to Inuit Culture” and answer the True/False questions that follow.

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/interculturalcompetence/?p=672#h5p-42

It is likely that there are cultural groups or subgroups within your own country that you know little about. These could be in your immediate vicinity, neighbourhood, community, city, or province. They could speak, for example, English, French, Russian, Turkish, Cantonese, or Swahili. Take time to read about these groups from different perspectives, using different sources that include (particularly) an insider and also an outsider perspective. Use that information to gain knowledge and remember to be wary of sources that rely on profiles that may unfairly describe people.

20

Cultural orientations or dimensions refer to generalizations or archetypes that allow us to study the general tendencies of a cultural group. This is helpful when we are trying to understand how most people in a cultural group tend to act or tend to think. By approaching generalizations in this way, we avoid creating stereotypes.

Studying cultural orientations will help you expand your knowledge and make more sense of how other people may think and others’ potential reasons for acting in a certain way. Remember that it is not about identifying what is the right or wrong way of behaving; it is about how we understand each other across cultures.

The following cultural orientations are informed by the work of Fons Trompenaars and Charles Hampden-Turner (orientations 1-5 and 7), and Edward T. Hall (orientations 6 and 8). These orientations combine values, behaviours, and attitudes to create dimensions that help us explain and understand generalizations across cultural groups.

As you explore these cultural orientations, keep in mind that:

How do we see ourselves in relation to others?

Individualism

Created by Griffin Mullins

from Noun Project

licensed under CC BY 3.0

Communitarianism / Collectivism

Created by Blake Thompson

from Noun Project

licensed under CC BY 3.0

Can you identify the value orientations in these statements? [Statements adapted from Lantz-Deaton & Golubeva, 2020, p. 39]

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/interculturalcompetence/?p=679#h5p-43

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/interculturalcompetence/?p=679#h5p-44

Print out the worksheet How I Understand Myself Based on Cultural Orientations [a link to a Word document] or on a piece of paper draw a horizontal line and mark the middle with an X or a vertical line. On each side, write “individualism” and “communitarianism” as shown below. Based on what you have learned, with what orientation do you feel more affinity? Do you feel your outlook and way of being and behaving are closer to one more than the other? Does it have elements of both? Where do you find yourself most of the time?

Mark with an “X” or a dot where you see yourself in relation to these orientations and, on the margins, write one or two examples of influences you had that moved you towards that orientation: for example, your background, family, education, type of work, organization, life experience, and so on.

Individualism __________________|__________________ Communitarianism

Save the sheet, you will use it later.

How do we define what is fair?

Universalism

Created by Adrien Coquet

from Noun Project

licensed under CC BY 3.0

Particularism

Created by Davo Sime

from Noun Project

licensed under CC BY 3.0

Read each situation carefully and then reflect on the questions that follow. Focus on which position you would take and how this may look from another person’s perspective, then write a short explanation of your position based on the questions asked.

Situation 1

An international student from India at a university in Switzerland approaches his professor to ask if it would be possible to submit an assignment a bit later since he just started working on it. The professor politely explains that it is not possible to offer an extension because that would be unfair to the rest of the students. The student highlights how well he is doing in the class, how much he participates, and the good relationship he has with the professor. As a reply, the professor explains that although he is a brilliant student and they have a good relationship, this does not mean the rules can be bent in the student’s favour.

[Examples adapted from Moser, 2021]

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/interculturalcompetence/?p=679#h5p-45

Situation 2

You are riding in a car driven by a close friend when he hits a pedestrian. You know he was going at least 60 km/h where the maximum allowed speed is 30 km/h. There are no witnesses. His lawyer says that if you testify under oath that he was only driving 30 km/h, it may save him from serious consequences.

[Examples adapted from Moser, 2021]

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/interculturalcompetence/?p=679#h5p-46

Studies have shown that when presented with similar cultural dilemmas, people from Switzerland, Canada, the USA, and Scandinavian countries generally lean on the importance to follow and abide by rules to create consistency and fairness. People in countries such as Venezuela, South Korea, Russia, and China generally pause to think about how fairness could be interpreted depending on the situation presented. These differences do not mean that certain people may or may not follow rules based on their culture, it means that we consider different things when defining what is fair.

Indicate on the worksheet where you see yourself in relation to these orientations. Write one or two examples of influences you have had that helped you move you towards that orientation.

Universalism __________________|__________________ Particularism

How do we get things done? How far do we get involved?

Task (specific)

Created by Tresnatiq

from Noun Project

licensed under CC BY 3.0

Relationship (diffuse)

Created by Tresnatiq

from Noun Project

licensed under CC BY 3.0

Which of the following are examples of task or relationship orientations?

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/interculturalcompetence/?p=679#h5p-47

Remember that when it comes to cultural orientations you do not “belong” to either one or the other. You may have general leanings towards one when you consider everything you do. However, you may still have elements of the other orientation based on what works best within your culture, your organization, and your personal life. As an example, if you work on a project with peers from Germany and Peru, it is very likely that the German nationals will emphasize the need for clear roles, instructions, and processes before spending time learning more about other people in the team. Conversely, your Peruvian peers may be more comfortable focusing on building a relationship, taking time to talk about each other, before you focus on project work. In this case, the key is to find a balance that works for everyone.

Indicate on the worksheet where you see yourself in relation to these orientations. Write one or two examples of influences you have had that helped you move you towards that orientation.

Task (specific) __________________|__________________ Relationship (diffuse)

How do we view status and hierarchy? Do we have to prove ourselves to receive status or is it given to us?

Achievement (egalitarian)

Created by Kervin Markle

from Noun Project

licensed under CC BY 3.0

Ascription (hierarchy)

Created by Neha Tyagi

from Noun Project

licensed under CC BY 3.0

Consider the following situations carefully and then reflect on the questions that follow. Focus on how you feel within the context of each situation and reflect on how you would react to or deal with the different ways of engaging in each meeting.

Situation 1 – Achievement (egalitarian)

You obtain your degree and are then offered a job in Denmark that corresponds with your qualifications and competence. When invited to discuss issues in a meeting, you notice that anyone, from the student intern to the VP, can participate or challenge decisions because everyone has the competence and/or capacity to do so.

Situation 2 – Ascription (hierarchy)

Examples adapted from Moser, 2021

You obtain your degree and are offered a job in Dubai that clearly reflects your qualifications and experience. During meetings, you notice you are encouraged to speak out, but only if you correspond with your peer in terms of seniority, gender, or social status.

It may be useful to think about the way you were raised—what your parents and professors expected from you. For example, if you were expected to always obey your parents without question, to refrain from interrupting professors in class, and to use titles when referring to your teachers (e.g., Dr. Lee or Prof Johnson), it is likely you are more comfortable with what constitutes an ascription orientation (often observed in people from India, China, and Japan). Conversely, if you are encouraged to voice your ideas, regardless of your gender or background, even if they seem to be against what your parents or professors think, and are comfortable calling your teachers by their first names (e.g., Allina or George), you may be leaning towards an achievement orientation (commonly seen in Canada and the United States).

Indicate on the worksheet where you see yourself in relation to these orientations. Write one or two examples of influences you have had that helped you move you towards that orientation.

Achievement (egalitarian) __________________|__________________ Ascription (hierarchy)

How do we express emotions? How do we manage them?

Affective (emotional)

Created by Vectoriconset10

from Noun Project

licensed under CC BY 3.0

Neutral

Created by Vectoriconset10

from Noun Project

licensed under CC BY 3.0

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/interculturalcompetence/?p=679#h5p-48

Research identifies people from Scandinavia, Russia, and South Korea as having the tendency to control their emotions when in public contexts. In contrast, many people from Latin America, Southern Italy, and most Middle Eastern countries seem to have a tendency to express their emotions more freely.

In addition to cultural orientations, personalities and the context of the situation also affect how people react, whether we are comfortable showing our feelings or trying to maintain a neutral exterior. Furthermore, cultures cannot be one or the other. The amount of visible emoting (the ease with which we display our feelings) differs greatly across cultures and, just as it happens with any other orientation, all actions, reactions, and interactions will be influenced by factors other than cultural tendencies.

Indicate on the worksheet where you see yourself in relation to these orientations. Write one or two examples of influences you have had that helped you move you towards that orientation.

Affective __________________|__________________ Neutral

How do we define and approach time?

Sequential time (monochronic)

Created by ProSymbols

from Noun Project

licensed under CC BY 3.0

Synchronous time (polychronic)

Created by Razmik Badalyan

from Noun Project

licensed under CC BY 3.0

Can you decide what time orientation is illustrated in the following situations?

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/interculturalcompetence/?p=679#h5p-49

The sequential time/monochronic orientation has often been observed in countries like Germany, Switzerland, Canada, and England. While the synchronous time/polychronic orientation seems to be common in countries like India, Colombia, French Polynesia, and Nigeria. It is important to remember that in addition to the overall tendencies towards one or another way to construct time, there will be variations across countries.

An important note about past-present-future orientations:

How we orient ourselves with regards to time goes beyond what is considered being punctual and our preference for focusing on one or several projects at the same time. How we regard time affects our outlook, where we look to identify goals, what is important for us to preserve or change, and what we consider when planning for the future. For example:

Indicate on the worksheet where you see yourself in relation to these orientations. Write one or two examples of influences you have had that helped you move you towards that orientation.

Sequential time(monochronic) _______________|_______________ Synchronous time (polychronic)

How do we relate to our environment?

Internal direction

Created by Adrien Coquet

from Noun Project

licensed under CC BY 3.0

External direction

Created by Adrien Coquet

from Noun Project

licensed under CC BY 3.0

Can you identify the orientations these statements refer to? [Some examples adapted from Moser, 2021]

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/interculturalcompetence/?p=679#h5p-50

People in countries with a tendency for an internal orientation include Israel, the United States, Australia, New Zealand, and Canada. People who often lean towards an external orientation include China, Saudi Arabia, and Spain. As with other orientations, remember that internal and external dimensions are influenced by other orientations, the situation, background, and personal experience. For example, a person may still wish another one “good luck” even if people from that culture have a strong internal orientation. Similarly, a person from a country mostly oriented towards an external orientation will still find value in some competition and will focus on achieving their goals. People do not belong to one or another, elements of both can be found in a group or community.

Indicate on the worksheet where you see yourself in relation to these orientations. Write one or two examples of influences you have had that helped you move you towards that orientation.

Internal direction __________________|__________________ External direction

How important is the context in communication? How much do we rely on context for communication?

Low context

Created by Nareerat Jaikaew

from Noun Project

licensed under CC BY 3.0

High context

Created by verry obito

from Noun Project

licensed under CC BY 3.0

Read the following situation and then reflect on the questions that follow. Position yourself behind both perspectives and then write a couple of sentences reflecting on the questions.

Situation:

(adapted from Lantz-Deaton & Golubeva, 2020, p. 36)

At a small university in Turkey, students are given a somewhat vague verbal assignment by a lecturer to write a 10-page paper on international development that will be due sometime before the end of the term. After class, an exchange student from Canada who has recently arrived approaches the lecturer and begins asking a lot of detailed questions: what the font size should be, if there is a word count, how many references to include, when the exact deadline is, which specific topics should be addressed, and so on. The lecturer becomes tired of all the questions and excuses themselves.

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/interculturalcompetence/?p=679#h5p-51

People from the Middle East, Asia, Africa, and Latin America, have been thought to be more high-context cultures, where there are unwritten rules and messages that cannot always be understood without background knowledge. People from countries with a low-context orientation tend to convey messages explicitly, very little is taken for granted, and the focus is on the words—the verbal message—more than on implicit messages. Countries with a low-context orientation include Canada, the United States, and most of Western Europe.

Indicate on the worksheet where you see yourself in relation to these orientations. Write one or two examples of influences you have had that helped you move you towards that orientation.

Low context __________________|__________________ High context

Take a look at the worksheet you completed and reflect on your orientations as a whole.

Hoffman, G. (2021). Black employee browsing laptop at table with many chairs. Pexels. https://www.pexels.com/photo/black-employee-browsing-laptop-at-table-with-many-chairs-7674998/

Samkov, I. (2020). Group Of People Studying Together. Pexels. https://www.pexels.com/photo/group-of-people-studying-together-5676744/

Aurelius, M. (2020). Photo of Woman Smiling While Using Laptop. Pexels. https://www.pexels.com/photo/photo-of-woman-smiling-while-using-laptop-4064641/

Wiguna, AP. (2018). Man Standing Beside His Wife Teaching Their Child How to Ride Bicycle. Pexels. https://www.pexels.com/photo/man-standing-beside-his-wife-teaching-their-child-how-to-ride-bicycle-1128318/

Fauxels. (2019). Photo Of People Doing Handshakes. Pexels. https://www.pexels.com/photo/photo-of-people-doing-handshakes-3183197/

Fauxels. (2019). Photo Of People Near Wooden Table. Pexels. https://www.pexels.com/photo/photo-of-people-near-wooden-table-3184431/

Pixabay. (2016). Man Holding Chess Piece. Pexels. https://www.pexels.com/photo/battle-board-game-castle-challenge-277124/

Fauxels. (2019). People Discuss About Graphs and Rates. Pexels. https://www.pexels.com/photo/people-discuss-about-graphs-and-rates-3184292/

Und, D. (2018). Photography of People Connecting Their Fingers. Pexels. https://www.pexels.com/photo/photography-of-people-connecting-their-fingers-1023828/

Piacquadio, A. (2020). Collage of portraits of cheerful woman. Pexels. https://www.pexels.com/photo/collage-of-portraits-of-cheerful-woman-3807758/

Piacquadio, A. (2020). Cheerful surprised woman sitting with laptop. Pexels. https://www.pexels.com/photo/cheerful-surprised-woman-sitting-with-laptop-3762940/

Cottonbro. (2020). Man in White Dress Shirt Standing Beside Woman in Pink Long Sleeve Shirt. Pexels. https://www.pexels.com/photo/man-in-white-dress-shirt-standing-beside-woman-in-pink-long-sleeve-shirt-4255412/

21

Nonverbal signals can be classified under different categories based on what they involve. Some examples include eye behaviour (e.g., staring, gazing, blinking, winking, avoiding eye contact), touching behaviour (e.g., hugging, patting, holding, kissing, and punching) proximity to others, facial expressions, posture, appearance and meaning of colours, head and hand movements, pauses and hesitations, and vocalizations (e.g., laughing, sighing, groaning, and shushing). Each of the nonverbal cues we utilize is culturally constructed and may follow unwritten rules. For example, laughing is a cultural universal, but the way this is expressed across cultures is different. Laughing out loud on a public bus may be acceptable in many Latin American countries, but may be seen as disruptive behaviour in Norway or England. Similarly, greeting someone with two kisses may be the common rule in Spain, but those rules may not be applied in the same way in Muslim countries where people also greet each other with two or more kisses.

Watch the video Non-verbal Communication Across Cultures (5’45”), where Prof Alan Jenkins discusses, in the context of business, how understanding nonverbal communication is key when interacting across cultures. Pay attention to the examples he provides.

Answer the following True / False questions based on Prof Jenkins’ talk.

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/interculturalcompetence/?p=887#h5p-52

When we interact interculturally, our body language helps us get a message across and make connections, for example, through touch, closeness, eye contact, head movements, facial expressions, and gestures that indicate openness and interest in what is being said. We may not always be aware of how we come across when interacting with cultural others, therefore we are often quick to make assumptions about other people based on how we interpret their behaviour.

You have learned how unfair this can be. It is not that you or the other person is being disrespectful, forward, ill-intentioned, disinterested, shy, cold, or choosing to ignore your personal space; you are simply using different codes. That is, you are each communicating nonverbally in ways that are not necessarily shared across cultures.

There are numerous categories of nonverbal behaviours. In the following activity, we will explore gestures, personal space, and greetings to help you expand your knowledge and understanding of different ways to interpret nonverbal signals.

What do the following gestures mean to you? Do you know what meaning they may have in other countries? Print out the word worksheet Nonverbal Communication – Hand Gestures and write your interpretation of each gesture.

Now watch the video The Definitions of Hand Gestures Around the World (5’15”). As you watch, check your answers to see if you matched the meaning intended.

Here are further examples of nonverbal communication across different cultures. Have you ever been in a situation where any of these could have influenced the way you felt during an interaction? Can you think of a situation when you could have done something that may have made the other person uncomfortable?

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/interculturalcompetence/?p=887#h5p-100

How big is your bubble? Consider the following situations within the context of pre-pandemic times. Picture them in your mind and think about what you would do, if anything.