Settler Colonialism in Acadie/Mi'kma'ki by Daniel Samson; Thomas Peace; and Renée Girard is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Settler Colonialism in Acadie/Mi'kma'ki by Daniel Samson; Thomas Peace; and Renée Girard is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

1

This is where we start our introduction!

Playing here. The interface is identical to WordPress.

I

1

Welcome to Acadie… or is it Mi’kma’ki… or Nova Scotia?

As we hope you will find over these modules, this is a question that does not have a straight forward answer. From the first day that Europeans set foot in the region, its definitions have been disputed and contested. For the Mi’kmaq, who have lived in this place since time immemorial, it has never ceased to be Mi’kma’ki. For French colonists, who called this place home for several generations before their forced removal from their farms, this place came to be known as Acadie. For the English, who first made a claim to this space in 1621 under European law, this place was called Nova Scotia.

Since the early seventeenth century, French and English interests have fought over this place. In fact, on three occasions during the seventeenth century, the English claimed nominal jurisdiction over the region. Neither empire, though, was significantly invested enough in the region to make a deep and lasting influence. Though after 1632, France worked to establish settlers in the Kespukwitk region of Mi’kma’ki – at the place they called Port Royal – this settlement grew slowly and between 1654 and 1670 – after the English captured the small settlement – it grew more-or-less independently from France. It was only in the 1680s and 1690s that France began to take more serious interest in the colony, issuing land grants and expanding its administrative purview. Alongside population growth at Port Royal, Acadian families moved away from this initial settlement, starting new communities at Beaubassin and Minas.

Tensions between England and France continued throughout these waning decades of the seventeenth century, with English attacks on Acadie hastening in the dawning years of the eighteenth century. In 1710, Port Royal was successfully captured and, in the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht, the British (as the English were known after 1708, following their union with Scotland) claimed mainland Acadie, while the French continued to occupy the Mi’kmaw districts of Unama’kik and Epekwitk. During all of this fighting and diplomacy, neither European kingdom directly engaged the Mi’kmaq in these discussions. Upon notice of this decision, Mi’kmaw leaders were upset that European powers would take such actions without their consent. When combined with events in Europe, this resistance made the middle of the eighteenth century one of the bloodiest moments in the region’s history.

In this lesson, we we will introduce you to the eighteenth-century world of Mi’kma’ki/Acadie/Nova Scotia using arcGIS online StoryMaps. Through this mapping tool, and two mid-eighteenth century primary sources, we will show you the landscape over which many of these histories took place.

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this lesson, you should be able to:

The activities in this lesson are embedded in the storymap below. You can work through this storymap within this online book or you can open the storymap in a new window. Opening in a new window will make the lesson easier to work through. Open storymap in a new window.

One or more interactive elements has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view them online here: https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/digitaldisruptions/?p=251

This module used historical GIS to demonstrate to you the power of digital mapping and the opportunities that GIS software provides for helping you imagine the past. The place that we are studying in this course was not understood in a singular way during the eighteenth century. Mi’kmaq, Acadian, French, English/British, and many others saw this places through very different eyes. With this in mind, we can use documents like the two you read here to help better represent these diverse realities, while also helping to better situate you – as students new to this time and place – into the geography of Maritime Canada.

2

1. Introduction

Usually, in a history course, we begin at the beginning, or at least early in the time period. In this case we need to start near the middle because the situation at the time was changing, and (frankly) pretty confusing. But it’s important that you understand the basic context of the story, so you know what’s going on. In this course we want you to think about a big theme ( settler colonialism), using a specific method (digital tools), in a specific place and time (Acadie/Mi’kma’ki in the first two thirds of the 18th century). But that basic issue of who’s doing what where – that is, “what happened” – is really important. But as we’ll see in this lesson, where it happened is equally important.

In 1710, British forces captured Port Royal, the capital of Acadie. In the subsequent peace (the Treaty of Utrecht, 1713), Acadia “with its ancient boundaries” was passed permanently to British control. That seems straightforward enough, except no one had ever determined where the boundaries were.

In the age of Google maps, we tend to take the information on maps for granted. They show us how to get somewhere, how to avoid traffic, and how long our journey will be. They seem fairly objective – it just represents what stuff is where – although we discover fairly quickly that algorithms can alter what information we’re offered: there’s that Thai restaurant you hadn’t known you were looking for until it popped up, and look, just yesterday I was scouting camping equipment and there’s MEC!

The map at the head of this page wants us to take its information for granted. Across that broad region now commonly identified as the Canadian Maritime provinces is written “New Scotland”. But look at our next map (below ) at this detail from Vicenzo Coronelli’s 1688, America Settentrionale, which shows that space as partly “Acadia”, and partly “Les Etchemins”. So why are the two maps so different? And who are the Etchemins? Which one is right? Or is either? And how can we tell?

Maps can tell stories and have points of view; they don’t always show you what is, but what the mapmaker wants you to see. This issue was very much on the mind of colonial officials in Britain and France in the 1750s as they struggled to define clearly what were the boundaries of Acadie, or Nova Scotia depending on your point-of-view. In 1710, British and New England troops captured Port Royal, the capital of the French colony of Acadie. Three years later, the subsequent peace treaty signed in Utrecht, Belgium, granted Acadie to the British. But where exactly was Acadie?

Like many treaties, the Treaty of Utrecht seemed straightforward. There was little doubt then, as now, that “the ancient limits of Acadie” centred on what we today call Nova Scotia. But beyond that little was clear. The British had captured the colonial capital, Port Royal, but after the treaty confirmed their possession they did little more than administer the town. Indeed, most Acadians were farmers living between 20 and 100 km away. They had little interaction with British officials and the British made little effort to govern these French Catholics. Most Acadians went on with their farming lives; many prospered in the new conditions of peace with “les Anglais”. By the 1740s, Acadians out-numbered the English-speaking Protestants by over 10 to 1. The British believed they were the sovereign power in what they called Nova Scotia, but in terms of governmental power, their reach was small.

Militarily, the British were perhaps even weaker. The Mi’kmaq, along with their Wabanaki allies in what is today New Brunswick and northern New England, were without doubt the preeminent military power in all that area. And yet, as we’ll see, their views, and in some ways even in their existence, played little role in drafting the maps, or the political understandings that would emerge in the period. In this instance, what we don’t see may be at least as important as what the mapmaker chose to show.

This module asks you to explore the same question that occupied those colonial administrators and diplomats: what was this place called Acadie? Where exactly was it located? Where were its boundaries?

Article 12 of the Treaty of Utrecht seems clear enough:

The most Christian King shall take care to have delivered to the Queen of Great Britain, on the same day that the ratifications of this treaty shall be exchanged, solemn and authentic letters, or instrument, by virtue whereof it shall appear, that the island of St. Christopher’s is to be possessed alone hereafter by British subjects, likewise all Nova Scotia or Acadie, with its ancient boundaries, as also the city of Port Royal, now called Annapolis Royal, and all other things in those parts.

For over forty years after the signing of the treaty of Utrecht in 1713, British and French diplomats attempted several times to establish the correct boundaries. And what about Mi’kma’ki? And the broader lands of the Wabanaki confederacy?

Unlike the administrators, you don’t need to draw lines on a map. You just need ask, in the mid-18th-century, who/what defined this place? These places? What does seem clear is that neither the British or the French held clear control of this territory. There were local areas where control seemed evident, but it was far from unimpeded power. Here, we’re following the ideas of historian Elizabeth Manke that it might helpful to think less about sovereign colonial states and more helpful to think about “spaces of power” – locations in this larger territory that the British dominated, ones that the French (or Acadians?) dominated, and ones that the Mi’kmaq dominated. Those spaces weren’t often clearly delineated on maps, but for us as historians looking back on that time it might make more sense to think about spaces rather than than states.

This lesson takes you through two short exercises where you’ll assess some of the evidence regarding the boundaries and territories of the British, French, and Mi’kmaq in the middle of the 18th century.

You’ll then write a short (500 word) reflection on the dispute, and how we should understand how the available evidence both helps and hinders a full understanding of the region in this period.

Hint: Ask yourself what it means that neither the British or the French could produce cartographic evidence of their own sovereignty – that the maps produced at the time were, as historian Jeffers Lennox argues – fictions, more the products of imperial aspirations and imaginations than of concrete realities.

2. Documents:

In these documents, we’ll begin working with hypothes.is, an annotation tool that facilitates close reading and discussion while reading online documents and webpages. [INSTRUCTIONS – is it the public account, or inside our text?]

We’ll be using this tool several times in the course and we hope you’ll develop some good discussions. But to get us started, and to illustrate something of its logic, we’ll use the following template:

In each lesson/document, we’ll ask you some general questions to get you started. Then, using hypothes.is, we ask you to read the documents and write three sets of annotations [i.e., not the three things we’re about to outline, but three items you identify for discussion].

– Share something of interest (either personal or scholarly) within the text. Something that caught your attention as being important or relevant to understanding the broader topic.

– Make a connection between one passage and another (explain [are how your point connects to another text in the lesson, or another text read in the course),

– Respond to or expand on someone else’s connection or point of interest.

There aren’t many wrong answers here, but there are better, more careful/thoughtful observations. Don’t be afraid to ask questions (good questions are as good as good answers!).

3. Maps

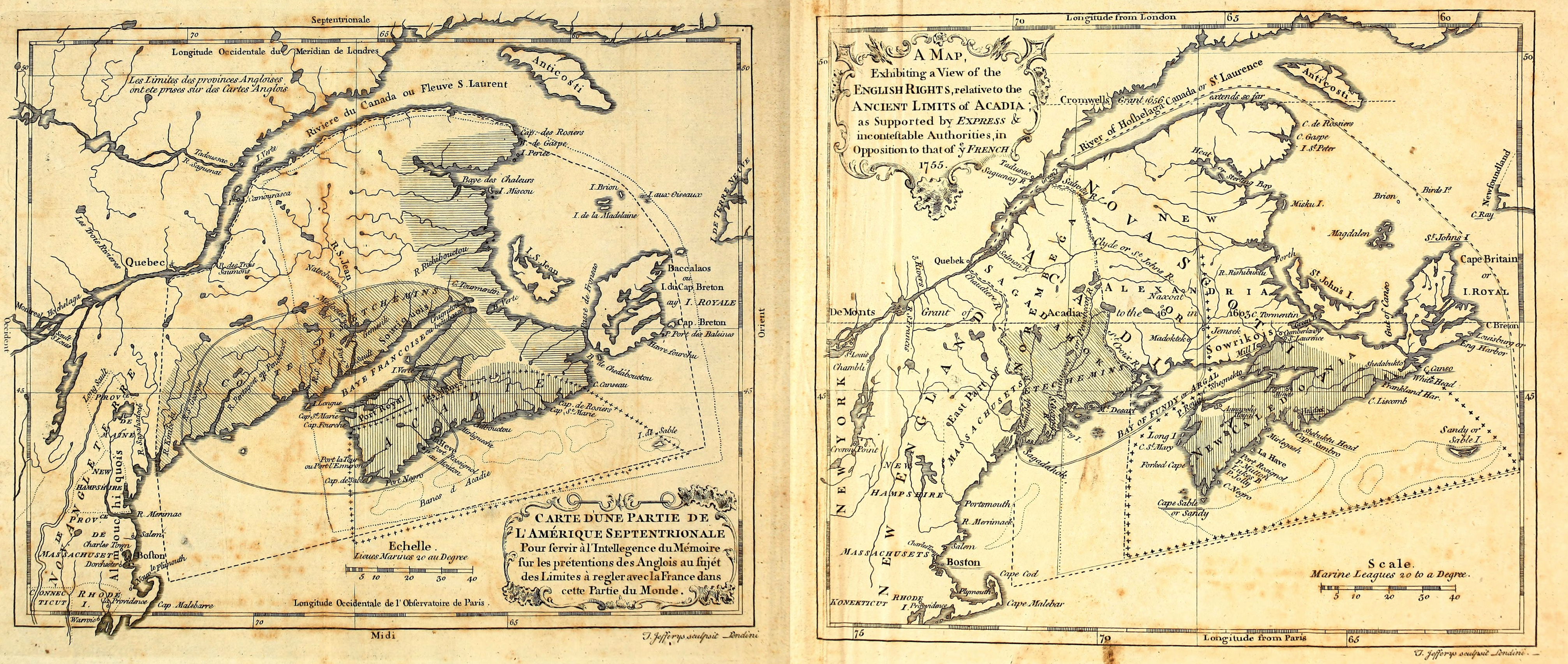

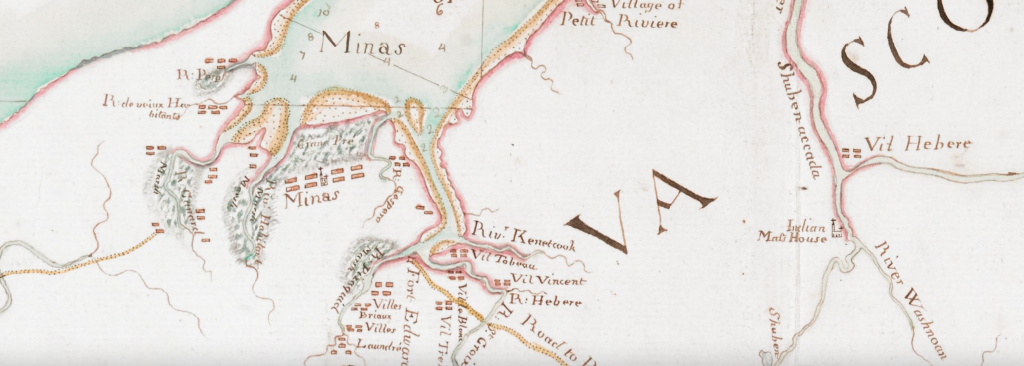

The maps immediately below are from the Memorials [cited above], they’re not easy to read (not least because the keys are printed elsewhere!] but you can see (a) very different identifications of where Acadie was positioned, and (b) on the British map (right hand side) a bolder Anglicised ascription of “Nova Scotia” and its separate provinces of “New Alexandria” and “New Caledonia”.

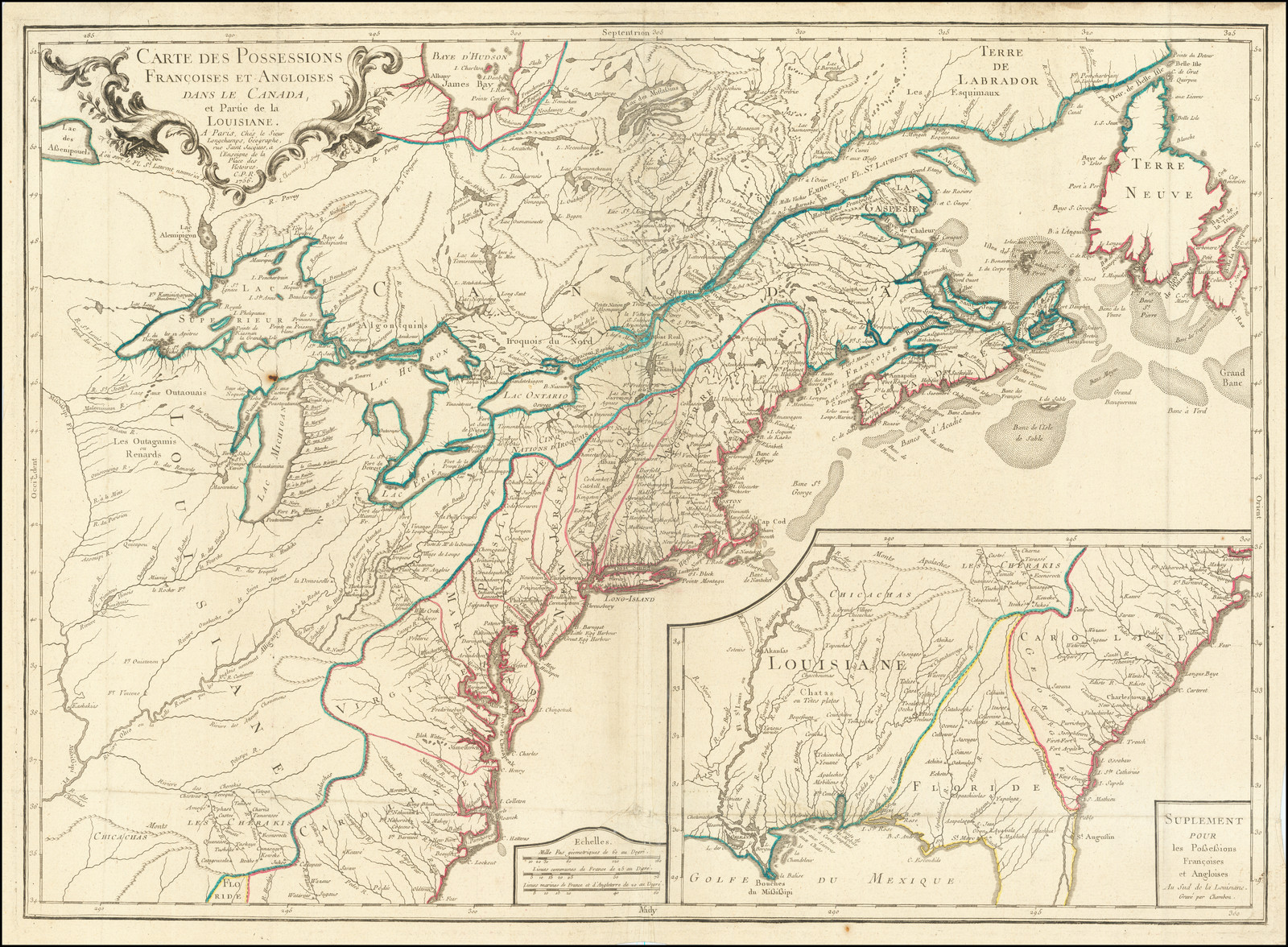

Contrast Mitchell’s A map of the British and French dominions in North America (1755) with Longchamps, Carte Des Possessions Francoises et Angloises dans le Canada et Partie de la Louisiane . . . 1756. [Note that the links under “Source” take you to hi-res versions where you can see mcuh great er detail.] Can you identify what marks Mitchell’s interpretation as representing the British viewpoint?

– – – – – – – – –

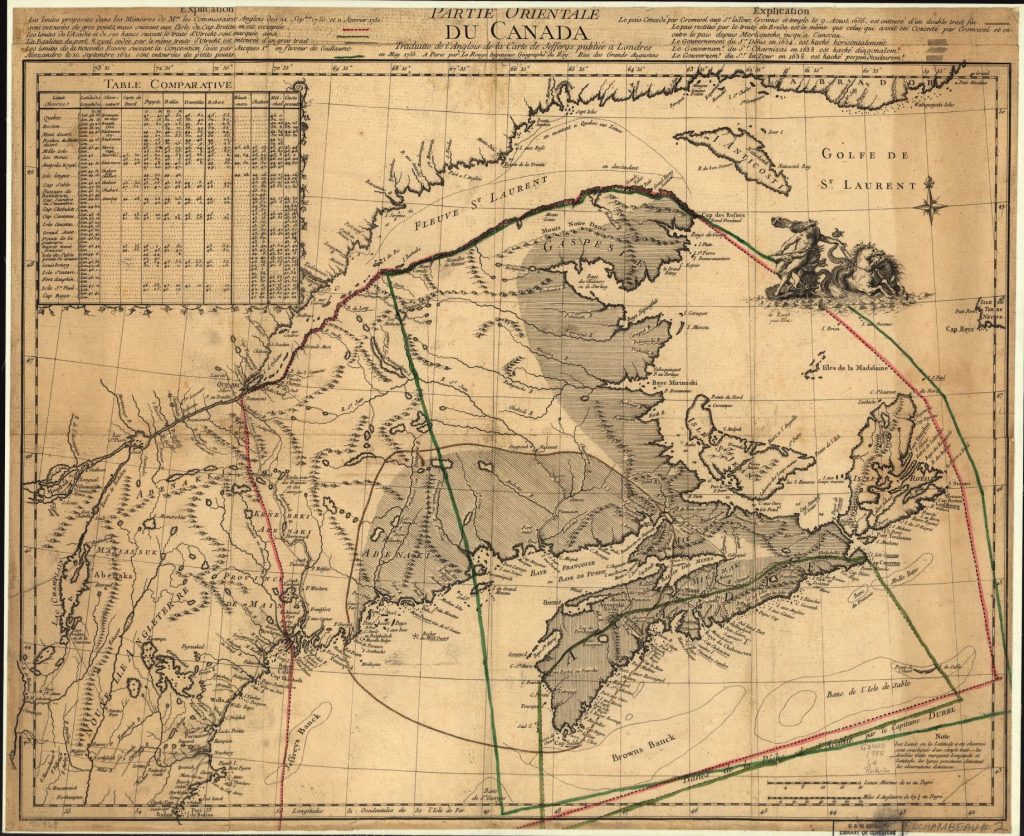

Thomas Jefferys, Partie orientale du Canada, traduitte de l’anglois de la carte de Jefferys publiée a Londres en May 1755.

https://www.loc.gov/resource/g3400.ar003100/

Dotted lines represent British (larger) and French (smaller) definitions of Nova Scotia/Acadie.

https://collections.leventhalmap.org/search/commonwealth:hx11z489p

Cyprian Southack, The Harbour and Islands of Canso. Part of the boundaries of Nova Scotia. To His Excellency Richard Phillips Esq. Captain General and Governor in Chief in and over his Majesties Province of Nova Scotia or Acadia (1720).

Partie orientale du Canada, traduitte de l’anglois de la carte de Jefferys publiée a Londres en May 1755.

A general topography of North America and the West Indies. Being a collection of all the maps, charts, plans, and particular surveys, that have been published of that part of the world, either in Europe or America.

Elizabeth Mancke, “Spaces of Power in the Early Modern Northeast,” in New England and the Maritime Provinces: Connections and Comparisons, edited by Stephen J. Hornsby and John G. Reid (Kingston and Montreal, McGill-Queen’s Press, 2005), 32–49.

Jeffers Lennox, Homelands and Empires: Indigenous Spaces, Imperial Fictions, and Competition for Territory in Northeastern North America, 1690-1763 (Toronto:,University of Toronto Press, 2017).

II

3

Settlers began arriving in Mi’kma’ki from France after 1632. For the most part, these people settled at Tewopskik, the Mi’kmaw name for the river presently known as Annapolis. The French called this place Port Royal and they labelled the river the Dauphin. As the population expanded, colonists built small settlements along the river rather than living more centrally around France’s fortifications. At its furthest extent, Acadian farms stretched for about 30 kilometres up river.

Rather than transforming forests into fields, the Acadians instead built earthen walls around the river’s extensive salt marshes. These walls – known as dykes – held back the tidal waters, which at this place rise about 15 ft to 18 ft. Once enclosed and drained, the marshes could dry out, desalinate, and then be used for growing crops.

In the settlement’s early days the population was small and grew slowly. By the early 1670s, the population had risen to about 350 people, or around 67 families. It did not take long, however, for the population to out grow this region. Within the decade, Acadian families expanded to other places around the Bay of Fundy. Like Tewopskik, the places where the Acadians settled tended to have very high tides and large expanses of tidal salt marshes. By the 1680s, Acadians had built new homes along Jijikwtuk, Setnuk, Knektkuk, Maqmekwitk, Amaqapskiket, We’kopekitk, and Siknikt. These were Mi’kmaw places, that the Acadians renamed Minas, Pisiquid, Cobequid, and Beaubassin among several other smaller places.

With a growing population, and continued political turmoil, France increasingly sought to understand who was living in this isolated colony. The first census of the Acadian population was taken in 1671, after French administrators returned to the region following sixteen years of putatively English rule. From that time on, censuses were taken of the French population in 1679, 1687, 1693, 1695, 1698, 1701, 1703, 1707, 1714, 1720, 1728, 1731, 1733, 1735, 1737, 1739, 1749, and 1752.

Censuses in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries were not like they are today. Sometimes censuses provide only basic information about a community, such as the total number of people, while at other times they provide considerably more information about the community itself. These more detailed censuses can provide us with important information about everyday life in Acadie. They must, however, be used cautiously.

There are three questions you must bear in mind when using this type of source:

Despite these challenges, censuses can be incredibly useful tools for understanding and learning about a population. In the three activities in this unit, we introduce you to three different style of census and some basic tenets of historical demography. As you work through each activity, create a single document that compares each census with the others. What does the structure of each census tell us about the purpose for which it was created?

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this lesson, you should be able to:

MS Excel

ArcGIS

One or more interactive elements has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view them online here: https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/digitaldisruptions/?p=38

Activity 1: The Gargas Census, 1687-88

This census was taken by a man who visited Mi’kma’ki only for a brief time. In 1687, Gargas, a French official charged with keeping the colony’s records, toured the colony and compiled this statistical table. We have transcribed and translated this document into an MS Excel spreadsheet. In doing so, to verify the transcription, we used formulas to double check the arithmetic. Cells in orange indicate places where Gargas’s math was wrong. Using the corrected data (the spreadsheet) let’s examine late-seventeenth century Acadian and Mi’kmaw society by comparing three different metrics: sex ratios, and the ratio of total population to livestock and land cleared.

To calculate a ratio take the total of one group and divide it by the total of another. For example, the ratio of Acadian male to female people along the Tewopskik was 231:219 or 1.05 males for each 1 female. The ratio of Acadians to Mi’kmaq in the area was 450:36 or 12.5 Acadians for each Mi’kmaq. If we look at livestock (horned animals) the ratios look a little different. This ratio of horned animals to Acadians is 580:450 or 1.29 horned animals for each Acadian. The ratio for woolen animals to Acadians was 687:450 or 1.53 woolen animals per Acadian. Finally, the ratio of arpents of land cleared relative to the Acadian population was 299:450 or 0.66 arpents per Acadian.

We have provided you with these numbers from Tewopskik as an example. In this activity, create similar ratios for the communities of Les Mines, Chicnitou, Pentagouet, Chibouctou, La Heve, Cape Sable, and Cape Breton.

Activity 2: The Gaulin Census, 1708

This census was taken about twenty years later the census in Activity 1. In 1708, Antoine Gaulin, a Catholic missionary charged with working in Mi’kma’ki, recorded the names, ages, and family structure of the Mi’kmaq with whom he was familiar. The census counts Mi’kmaq living in communities at Port Royal, Cape Sable, La Heve, Mines, Mouscoudabouet, Cape Breton, and Cheguenitou. Pierre La Chasse, the Jesuit missionary at Pentagouet also enumerated the Penobscot there. This part of the census though is a little different. La Chasse did not record people’s ages and grouped them by household rather than family. Two other communities of Indigenous Peoples were also enumerated, the Kennebec on the Kennebec River and the Wolastoqiyik on the Wolastoq River. There, however, the census taker only listed men who could bear arms and therefore did not provide enough information to adequately understand the population.

In this activity, we would like you to develop an expertise about one of the Mi’kmaq communities enumerated by Gaulin. In addition to calculating sex ratios, for this activity you should also create an age pyramid like the one displayed in the Documents section below. This graph was build using this spreadsheet. Replace this data with the data specific to the community that you examined.

Once complete, write a short 250 paragraph answering these two questions: How does this census reshape your understanding of this region? What does this census teach us about the role of the Catholic Church in Mi’kma’ki?

Activity 3: The Le Roque Census, 1752

In 1752, the Sieur Joseph de la Roque, the King’s Surveyor in Isle Royale was commissioned to tour all of the ports, harbours, and creeks on Isle Royale (Unamakik/Cape Breton Island). In conducting his survey, la Roque listed all of the people he encountered in his travels, their ages and family relationships. You will notice that this census is considerably different than the other two types of enumerations. As a narrative census, la Roque presents us with rich detail about the diverse French settlements on Isle Royale. In this activity we would like you to choose one of the communities la Roque enumerated. From the information that he provides, build a spreadsheet that allows you to compare this census with the other two that you have studied. Can you calculate sex ratios, build age pyramids, and conduct other calculations that allow you to compare these communities with each other and those from elsewhere in the region several decades earlier?

In his census, la Roque also provides considerable geographic information about these communities and the people who live there. Using ARCgis online, create a map of the geographic information about your community. To do this, click on the “map” tab on the top the dashboard of your public ARCgis online account. Once your map has opened, click on the “add” tab in the top left hand corner and click on “Add Map Notes.” Name your notes after the community you have chosen and remember to save your map. Now that you have created this map and layer add whatever geographic information you think is useful to display by making points, lines, or areas. Here, you may want to consider from where people came, documenting la Roque’s travels, and other types of information that can be geographically represented.

4

The Catholic Church was a pivotal institution in Mi’kma’ki and Acadie but was slow to grow over the seventeenth century. Some of the first Europeans to visit this area were Catholic priests like Pierre Biard and Enemond Masse but, because of regular conflict with the English, it was not until the 1680s that the church began to establish itself in the region, with local parish churches taking root in places like Minas and Beaubassin. Though they were never well supported, these parish churches played a significant role in structuring daily and seasonal life, especially after 1713, when Britain allowed Catholic priests to continue working in the space they now called Nova Scotia.

By the 1710s, the Catholic church was well entrenched in the culture of the region. As we have already seen with the 1708 census, by that decade missionary Antoine Gaulin had begun to lay the groundwork for the church’s relationship with the Mi’kmaq. If you refer back to the documents we studied in lesson 1, you can also see the importance of the church in how Acadian society was structured around parishes. A parish is a geographical unit, centred around a church and usually – though not always in Acadie – assigned a priest. In a place like Acadie, and a time period like the eighteenth century, the parish church was usually the only institutional structure in a community. As such, it served both a religious role, but also a political, and social role as well.

The most important work of the church was to ensure that the people living in this place received Catholicism’s Holy Sacraments. Though records of Mass and first communion were either not kept or have not survived, the church was much more diligent in recording baptisms, marriages, and burials. By the turn of the eighteenth century, the recording of these rites of passage had become part of Catholic law and these church records served a purpose not unlike a birth certificate, marriage license, or death certificate do today. Unlike today, though, the rules about the keeping of these records developed during a time when church and state were deeply intertwined. Knowing when a person was born, married, and died was important information for legal proceedings (such as inheritance) and state building (such as taxes). The church – with its local footprint in a parish – served as a tool for recording and safe keeping this information.

Much like the censuses explored in the last chapter, parish registers can be difficult sources to use. On the surface, each record appears to convey very little information. Usually all that is noted in these records are the names of participants, the date, their relationship to each other, the type of religious event (usually baptisms, burials, and marriages), and the name of the priest. Individually, these records provide very little information about a community. Taken together, however, these records can be much more powerful, revealing to us important information about prominent individuals and families within a community.

To get a feel for parish registers, we have transcribed and translated 22 parish records for you. These records are from the Acadian community of Beaubassin during the early-1720s. Hand-written, and in French, there are thousands of these records available. These twenty two were selected as being both representative of the larger collection and yet they are also unique given that they also include a handful of Mi’kmaw participants.

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this lesson, you should be able to:

Analysis 1: Read through these records and make a list of the information that we can learn from this type of record.

Analysis 2: Create a spreadsheet that records all of the dates noted in the records. How might we be able to use this information to discern information about the people whose lives are recorded in these registers.

To develop a deeper understanding of what parish records can teach us, we will use the open source tool Gephi to build a basic social network.

If you have not done so already, download and open Gephi.

Gephi is a fairly straight forward program that helps reveal connections between records. To do social network analysis with Gephi, you need two types of information:

For these religious acts, there are four types of relationships we will use:

The word “Act” is used for relationships that are unclear. In these cases, all we know is that these two people appeared in the same record together; the record does not provide any additional information about the relationship between these nodes.

Now, let’s build up the files that we will need to import into Gephi to conduct our social network analysis. To do this, you will need to create several comma-separated value (CSV) files. It is easiest to do this in MS Excel. Just make sure that when you are saving your file, you make the file type .csv rather than using Excel’s default setting. If you know how to build an Excel file, go ahead; if you’re new to Excel, watch this quick video introduction to Excel.

To help better organize this information, we will use the first baptism in the transcriptions that we have provided to you as our example:

“On the first day of the month of June of the year seventeen hundred twenty-three I the undersigned René Charles de Breslay Missionary priest and parish pastor of Lisle de St. Jean and other dependencies and vicar general of Monsignor bishop of kebec baptized for lack of a parish priest and doing the curial functions of this parish of Beaubassin Joseph son of Michel Chikaguet sauvage Mikmaque and of Marguerite Bernard his wife aged about one month The godfather Guillaume sire inhabitant of this parish The Godmother Anne Blanchard wife of claude Bourgeois also inhabitant of the said parish which declared not to know how to sign, as required by the ordinance.”

To transform this record into information that is readable through Gephi, make a table like this that includes all of the information you know about each person. This will become the basis for your Node Attributes table. Be sure to save it as a .csv file (call it Beaubassin Node Attributes)

| Record | ID | Role | Ethnicity |

| 1 | Joseph | Baptized | M |

| 1 | Michel Chikaguet | Father | M |

| 1 | Marguerite Bernard | Mother | M |

| 1 | Guillaume Sire | Godparent | F |

| 1 | Anne Blanchard | Godparent | F |

| 1 | Claude Bourgeois | Spouse of Anne Blanchard | M |

One difference between this table and the record itself is that we have chosen to record Marguerite Bernard as Mi’kmaq. We have made this choice because Marguerite’s identity is not otherwise noted. Though it might be more accurate to list her identity as uncertain, if you look at the next record we have transcribed, cécile – wife of François 8abniketch – it is clear that she is Mi’kmaq (though again without annotation). We have chosen to interpret the identity of ethically unidentified married partners and children as the same as their ethnically identified partners or parents. These are important decisions that need to be made in advance, in order to ensure your records are consistent and that your methods are transparent.

As you build this table there are some records that provide more detail than what we have provided in this example. One good example is the role of the ondoié. This French word is difficult to translate. It refers to someone other than a Priest who performed a baptism. The term ondoiement means “emergency baptism.” Give some consideration to how you will add people in this role to your tables.

Once complete, you will want to standardize your records. To do this, click on the “data” tab at the top of your screen. Click on “sort.” In the menu, sort by “Name.” Now scroll through your records to ensure that there are no records that will lead to confusion. For any person with the same name but clearly two different people (such as the two Anne’s in baptismal records 12 and 13), rename them using numbers to distinguish one person from the other. Because it is clear that this is not the same “Anne” being baptized, use the label “Anne – 1” for the person in Act 12 and “Anne – 2” for the person in Act 13. Keep note of these decisions in a separate file as you conduct your work. This way you will be able to remind your future self about the decision you made here. If you were doing a larger project, you would also want to consult the work of genealogists like Bona Arsenault and Stephen White.

Once you have made this table, it is easier to identify the relationships involved in each baptism. Now, it is time to make your relationships table (call it Beaubassin Relationships). Here, starting with your primary person (Joseph, in this case), record each of the relationships found in this record. Your table should look like this, with the person in the source column decreasing in frequency as you work through each participant. For this record, each person should appear five times. Here is what the table should look like:

| Record ID | Source | Relationship | Target |

| 1 | Joseph | Child | Michel Chikaguet |

| 1 | Joseph | Child | Marguerite Bernard |

| 1 | Joseph | Godparent | Guillaume Sire |

| 1 | Joseph | Godparent | Anne Blanchard |

| 1 | Joseph | Act | Claude Bourgeois |

| 1 | Michel Chikaguet | Spouse | Marguerite Bernard |

| 1 | Michel Chikaguet | Act | Guillaume Sire |

| 1 | Michel Chikaguet | Act | Anne Blanchard |

| 1 | Michel Chikaguet | Act | Claude Bourgeois |

| 1 | Marguerite Bernard | Act | Guillaume Sire |

| 1 | Marguerite Bernard | Act | Anne Blanchard |

| 1 | Marguerite Bernard | Act | Claude Bourgeois |

| 1 | Guillaume Sire | Act | Anne Blanchard |

| 1 | Guillaume Sire | Act | Claude Bourgeois |

| 1 | Anne Blanchard | Spouse | Claude Bourgeois |

You’re almost ready to do some social network analysis. Before you import your spreadsheets into Gephi, there are a few additional changes you need to make.

In the first .csv (Excel) file (Node Attributes), you will notice that it is comprised of four columns: Record, ID, Role, and Ethnicity. This file will create the nodes in the social network we will build. A node is the entity (in this case a person) who enters into a relationship with another node. Gephi will have difficulty reading this file because you have two Annes. Before making any changes, save the file under a different file name. Then, to make the file more legible, remove all of the duplicated people (ensuring that you have numbered people who are distinct). Taking this action also means you need to remove the “Record” and “Role” columns because they are no longer necessary.

You can now import this file. To do this, click on the word “File” in the top left-hand corner, then click on “import spreadsheet.” Click on the Node Attributes file and follow the instructions. Once complete, your screen should look like this:

There is nothing yet here to analyze; it’s simply a random graph of all the people included in your “Beaubassin Node Attributes” file.

Now it is time to add the relationships between each of the nodes/people. For this, you will use the “Beaubassin Relationships” file. This file creates what are called “edges.” An edge forms the relationship between two nodes. The two most important columns in this file are “source” and “target.” As you have likely noticed, these columns list the same names as the “ID” column in the “Node Attribute” file. The “source” and “target” columns determine the nodes in relationship with each other. The “Relationship” column gives an attribute to the relationship. In this case, it describes the relationship between the two nodes (child, parent, spouse, and “act”).

In order for the software to read your file, you need to have an additional column: “type”. You will need to add this column between the “Relationship” and “Target” columns. This additional column determines whether the edge is directed or undirected. For our purposes we are using undirected edges and do not need to consider this further at this time. Just enter “undirected” in this column on each of the rows (use cut and paste). Your table should now look like this:

| Record ID | Source | Type | Relationship | Target |

| 1 | Joseph | Undirected | Child | Michel Chikaguet |

| 1 | Joseph | Undirected | Child | Marguerite Bernard |

| 1 | Joseph | Undirected | Godparent | Guillaume Sire |

| 1 | Joseph | Undirected | Godparent | Anne Blanchard |

| 1 | Joseph | Undirected | Act | Claude Bourgeois |

| 1 | Michel Chikaguet | Undirected | Spouse | Marguerite Bernard |

| 1 | Michel Chikaguet | Undirected | Act | Guillaume Sire |

| 1 | Michel Chikaguet | Undirected | Act | Anne Blanchard |

| 1 | Michel Chikaguet | Undirected | Act | Claude Bourgeois |

| 1 | Marguerite Bernard | Undirected | Act | Guillaume Sire |

| 1 | Marguerite Bernard | Undirected | Act | Anne Blanchard |

| 1 | Marguerite Bernard | Undirected | Act | Claude Bourgeois |

| 1 | Guillaume Sire | Undirected | Act | Anne Blanchard |

| 1 | Guillaume Sire | Undirected | Act | Claude Bourgeois |

| 1 | Anne Blanchard | Undirected | Spouse | Claude Bourgeois |

Use the same process as you just did for “Beaubassin Node Attributes” to load the “Beaubassin Relationships” file into Gephi. This time, though, when you get to the “Import Report” (the third pop-up) change the selection on the bottom right of the pop up box from “New workspace” to “Append to existing workspace.”

Once complete, your screen should look like this:

Now you have a social network graph to explore. Before doing so, though, click on the “Data Laboratory” to see how Gephi has merged your two files.

Returning to the graph, make navigating the graph easier by changing the node colours to represent ethnicity. To do this, click on “partition” underneath “Nodes” and “Edges” in the top left side of the screen (“nodes” should be shaded dark grey). A drop down box will appear. Click on “ethnicity.”

Now, change the edge colours to represent the type of relationship. To do this, click on the word “Edges” above the word “Partition.” Click on “Partition” again and choose “interaction.” Now your graph is a little easier to understand. Your screen should look something like this:

Another way to interpret the graph is to look at what is called “degree.” Beside the words “Nodes” and “Edges” on the left, you will notice a symbol with three circles. Click on it. Then click on “ranking.” Then choose “degree.” In the boxes that appear keep “min” at 1 and raise “max” to 14. You should now see three larger nodes. In the graph box, click on the icon with an arrow and question mark, then click on one of the larger nodes. The box on the left will provide you with information about this node. If you have done everything right, this should be Michel Poirier, Francois Poirier, or Michel Bourk – 1. Use this clicker to explore other parts of the graph.

Next play around with the layouts in the bottom left hand corner of the screen.

Turning to the right of the screen, run the various statistical tools listed there. As you run these tools, Gephi will analyze our network. You will see numbers appear as you click these buttons. If you turn back to “Data Laboratory” you will also see that Gephi has provided analysis for each of your nodes. You can rank each of these categories to learn more about your specific network. The following list describes some of the basic categories for you to explore:

Now that you have explored the basic functionality of Gephi, return to your initial list of information that you gleaned from these twenty-two parish records.

Now that you have done a little bit of social network analysis, why not investigate social networks at Port Royal using the Port Royal parish registers available through the Government of Canada’s Open Data project.

III

5

Since the beginning of Christianity, religious men and women have travelled the world to spread the word of their God to convince pagans and those they saw as infidels to embrace their faith. The encounter with America opened up a new reservoir of souls to harvest and stimulated the creation of “missions” throughout the newly discovered continent.

Like the other Catholic powers, Spain and Portugal, France intricately linked conversion and colonization in what they considered their civilizing mission. Once the project of establishing a colony took form, the French monarch, referred to as “the Most Christian King,” quickly encouraged the conversion of the Indigenous peoples. Bringing the word of God to New France would save souls and help control the Indigenous population once they joined the great catholic family. Otherness in the seventeenth century was not a question of race but more one of allegiance. If you recognized the rule of the French King and the Pope, you were considered a French subject. And the number of subjects a ruler had reflected the magnitude of his power.

Both men and women from different religious congregations came to New France. However, they had different occupations. The nuns devoted themselves to education and medical assistance. Missionary work, which often implied living with Indigenous people, was primarily masculine. The first missionaries to arrive in Acadie/Mi’kma’ki were members of Recollect, the Jesuit and the Capuchin orders. They were joined towards the end of the seventeenth century by secular priests, Sulpicians and members of the Missions Étrangères. While they had different approaches, they were all dedicated to a common mission, the spiritual salvation of Indigenous people.

The first challenge they faced was to find an efficient way to convey the message of their God to non-sedentary populations whose language they did not know. How could they introduce the gospel to people with whom they could barely communicate? The missionaries soon realized their only option was to learn the different languages. The best way to do that was to live with the Indigenous people, which implied travelling with them, as the Mi’kmaq and the Wolastoqiyik were not sedentary. While some priests remained in parishes to serve the settlers, missionaries constantly moved from one settlement to another as their hosts settled close to the sea during summer for their fishing activities and moved inland in winter to hunt. However difficult life this life was, it gave them the occasion to create strong links with the Indigenous communities they were serving and to observe their customs.

From their initial presence in Acadia, missionaries had to provide regular reports to their superiors in France, Rome and eventually Quebec. Some of those reports were published as Relations, although only after a certain amount of editing. These documents are valuable ethnographic work, even if some of the authors’ biases twist the image they give of the Indigenous communities. The missionaries’ correspondence, where they describe their experience among the Mi’kmaq, Wolastoqiyik and Abenaki, is another document that provides relevant information about life in Acadie/Mi’kma’ki. They reveal not only the success but also the difficulties and frustrations the religious men face in their effort to carry out their mission.

Although the deep desire to save souls was their main incentive, the conversion of the Mi’kmaq, Wolastoqiyik and Abenakis to Catholicism was part of a broader imperial project. Providing new subjects for the King of France would help prevent the spread of the protestant heresy in North America. Because of their close connection to the Indigenous nations of Acadie/Mi’kma’ki and the influence they could exert, the French authorities used the missionaries to prevent them from allying themselves with the English. Meanwhile, the English saw the missionaries as a menace and the main reason why the Acadians and Indigenous people would not take the oath of allegiance.

The political situation affected the work of missionaries who actively participated in the French-English conflict, some even joining their Indigenous allies in war expeditions against the English. In Acadie/Mi’kma’ki, the missionaries served France as well as God.

In lesson 3.1, you will find relations and letters written by some missionaries who stayed with the different Indigenous communities throughout the 17th and 18th centuries. The first three documents are from Jesuits: Pierre Biard, Julien Perrault, and André Richard. The Jesuits were a well-organized religious order whose main objective was the evangelization of infidels. They had missions in Europe, Asia, and South America. The following two are from the Capuchin Ignace de Paris and the Recollect Chrestien LeClercq, both from mendicant orders part of the Franciscan family. The last three are from missionaries from the Missions Étrangères de Paris, an order also devoted to evangelization.

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this lesson, you should be able to:

Those documents will allow you to understand the many challenges those missionaries faced. You will also find very different perceptions of the Mi’kmaq.

This lesson consists of 3 parts, detailed in the tabs below

One or more interactive elements has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view them online here: https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/digitaldisruptions/?p=40

Julien Perrault, “Relation of certain details regarding the Island of Cape Breton and its Inhabitants”, 1635. In Reuben Gold Thwaites, The Jesuit Relation and Allied Documents vol. VIII (Cleveland, Burrows Brother Company, 1897), p.157-167.

André Richard, “Of what Occurred at Miscou”, 1644 in In Reuben Gold Thwaites,

Ignace de Paris, excerpt from “ Letter from the Capuchin Father R. P. Ignatius ” in PH. F. Bourgeois, Les Anciens Missionnaires de l’Acadie Devant l’histoire ( Shédiac, Presses du moniteur acadien, 1910), p.88-97.

Chrestien LeClercq, New Relation of Gaspesia, 1691, excerpts from chapter VII, “On the Ignorance of the Gaspesians”, William F. Ganong, trans. (Toronto, The Champlain Society, 1910), p. 131-135.

Louis-Pierre Thury, extract from “a letter from Sieur de Thury, missionary, October 11. 1698”

Pierre Maillard., Letter Oct 1rst, 1738 and Letter Oct 13th, 1751, and Maillard letter to grand vicar Lalane.Pierre

Jean-Louis Le Loutre, Letter Oct 1rst, 1738.

6

As you have seen in lesson 1, missionaries’ letters inform us of the social dynamics that prevailed in Acadia. As privileged witnesses, they provide glimpses of the daily life of the Mi’kmaq, the Wolastoqiyik and the Abenakis with whom they had to share their life. They illustrate the many difficulties the missionaries faced while trying to adapt to life among people whose visions of the world were not shaped by western and Christian tenets. While distorted by eurocentric lenses, their testimonies serve as valuable ethnographic documents.

In lesson 2, you will access other types of documents that provides valuable information on the interaction of the Indigenous, French and English populations in Acadie/Mi’kma’ki; captivity narratives, deed of sales of enslaved people.

You will find that some of the words used in this lesson’s documents are considered offensive and expressions of racism. We have left them because they are part of the original texts and historical context.

As you have noticed in previous documents, we have left the word “Sauvage” in French. The English translation “savage,” generally used for this word, is misleading as it implies a dimension of violence and cruelty that does not correspond to the french meaning. The word “Sauvage” comes from the Latin silva, which means forest. It referred in the early modern world to ‘wild’ plants as opposed to cultivated plants and people who lived in the forest. Through time it took the meaning of ‘uncivilized’. It is a pejorative and homogenizing term that has generally been used to describe Indigenous people without referring to their nations or their names. It has contributed to the dehumanization of Indigenous peoples.

In the captivity narratives, you will notice that both Rowlandson and Gyles refer to Indigenous women as ‘squaw’. The term is an adaptation of an Algonquin word meaning woman. However, it has become offensive because of its usage to demean and objectify Indigenous women.

The term ‘negro’ is another sensitive word. The Spanish first used it as an evolution from the Latin word ‘niger’, which translates as black. Like the other terms mentioned above, it has been used as a pejorative way to amalgamate all people of African descent and has a strong racist connotation. In a similar way the term Panis, which is supposed to refer to a specific Indigenous nation in the Illinois, was applied to all enslaved Indigenous people in New France.

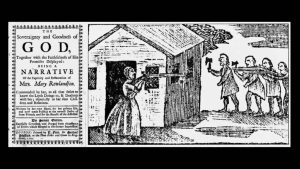

First activity; Using Voyant tool, you will analyze and compare two captivity narratives.

and

John Gyles, Memoirs of odd adventures, strange deliverances, etc., in the captivity of John Giles, Esq., commander of the garrison on Saint George River (Boston, in N.E. Printed and sold by S. Kneeland and T. Green, in Queenstreet, over against the prison, 1736).

https://archive.org/details/memoirsoddadven01gylegoog/page/n4/mode/2up

***

Captivity narratives were very popular in the 17th and 18th centuries to the point of becoming a literary genre. The stories written by men and women who had returned from captivity provided fascinating stories filled with drama, action and emotion. Some read like adventure stories, while others were reminiscent of religious journeys.

For the New England colonists, Rowlandson and Gyles’ narratives related to their familiar world, a violent environment torn by conflicts and wars and where being taken as a prisoner was a common risk.

You may wonder about the relation between the testimonies of two Puritans from New England and Acadie/Mi’kma’ki. As you have seen in Module 1, the definition of territories was not as clear as French and English maps lead us to believe. While both empires attempted to control areas comprised between now Cape Cod and the northern part of Acadie/Mi’kma’ki, it was still Indigenous land and deeply interconnected.

Mary and her three children were captured in February 1676 by a group of Algonquian-speaking Wampanoags, Narragansetts and Nipmucs during the conflict known as King Philip’s war, or Metacom’s war (1675-1676), one of the bloodiest conflicts in American history. The hostilities arose from an accumulation of frustration provoked by the relentless encroachment of English newcomers on Indigenous land. Both sides committed atrocities, and the relationship between the English settlers and Indigenous peoples was deeply affected.

While none of the Wabanaki nations participated in this conflict, they suffered its repercussion as New Englander’s hostility extended indistinctively to all Indigenous nations, affecting their relations with the Mi’kmaq and the Wolastoqiyik. The proximity of the Mi’kmaq to the French made things even worse.

Gyles’ captivity inscribes itself in this context of war and tension between New England, New France and the Wabanaki Confederacy. In August 1689, John Gyles, aged nine, was captured by a party of Wolastoqiyik in Pemaquid, Maine. His mother, sisters and brothers suffered the same fate, but his father was killed during the attack.

Mary Rowlandson spent eleven weeks with her captors, relocating from place to place until her husband ransomed her back. John Gyles’ captivity lasted six years with the Wolastoqiyik. He spent another three years in Acadie/Mi’kma’ki after being sold to a Frenchman before returning to Boston as a free man.

We can imagine how traumatizing these experiences were and how they affected their perception of their captors. Mary’s young child died in her arms. Her other two children were separated from her. She suffered from cold and hunger. While John survived physical torments, he saw his brother tortured to death. Both feared losing their lives. However, as puritans, being incorporated into an Indigenous society AND among Catholics made them dread losing their “Englishness” and their souls as much as their lives. Only their faith in God and their hopes to be eventually ransomed and returned to their people helped them to survive their ordeal.

Despite having privileged access to the daily life of their captors, their testimonies inform us more about the lens they used to translate their experience than the communities they integrated. Having been forced into participation in the life of what they considered uncivilized people, their accounts gave reassurance that one could return. There could be redemption for what was perceived as God’s punishment of sinners. It also proved to the readers that captives could retain their identity and not be contaminated by those they depicted as cruel and barbarous. By over-amplifying specific aspects of Indigenous societies, the captivity narratives contributed perpetuating the stereotypes that fed the image of the ‘savage Indian’.

Download both documents simultaneously in Voyant to compare Mary Rowlandson and John Gyles’ accounts. Look for meaningful words that indicate each author’s particularity. What words stand out in both texts, and how do they reflect the author’s state of mind? What are the differences, the similarities?

How much can we rely on those texts to better understand Indigenous societies ? How does Voyant help you get a better grasp of the text?

Second activity; ????

Rowlandson and Gyles captivity narratives are well known because they were published and provided exciting stories of settlers who had survived and kept their moral integrity after living among those they considered uncivilized. However, many other captivity experiences remain untold, those of the Indigenous and African descent people who were enslaved by the French and the English. We rarely hear their voice but legal documents, primarily deeds of sale or inheritance reveal how they were an inherent part of the Acadian society.

Because of the close trade Acadia had with the West Indies and New England, most of its enslaved people were men and women of African descent. However, Indigenous people were also enslaved.

You will find here documents that inform you about the enslaved people in Acadia. They are treated as commodities, merchandises to be exchanged, so unlike in Rowlandson and Gyles narratives, you will not hear their voices. They remain silent but they were an inherent part of Acadia’s society and participated actively in the colony.

Tool: Voyant Tools [works wrt Gyles et al, but not elsewhere]

Activity: Students will draw out meaningful terms and compare how they are used in both documents.

IV

7

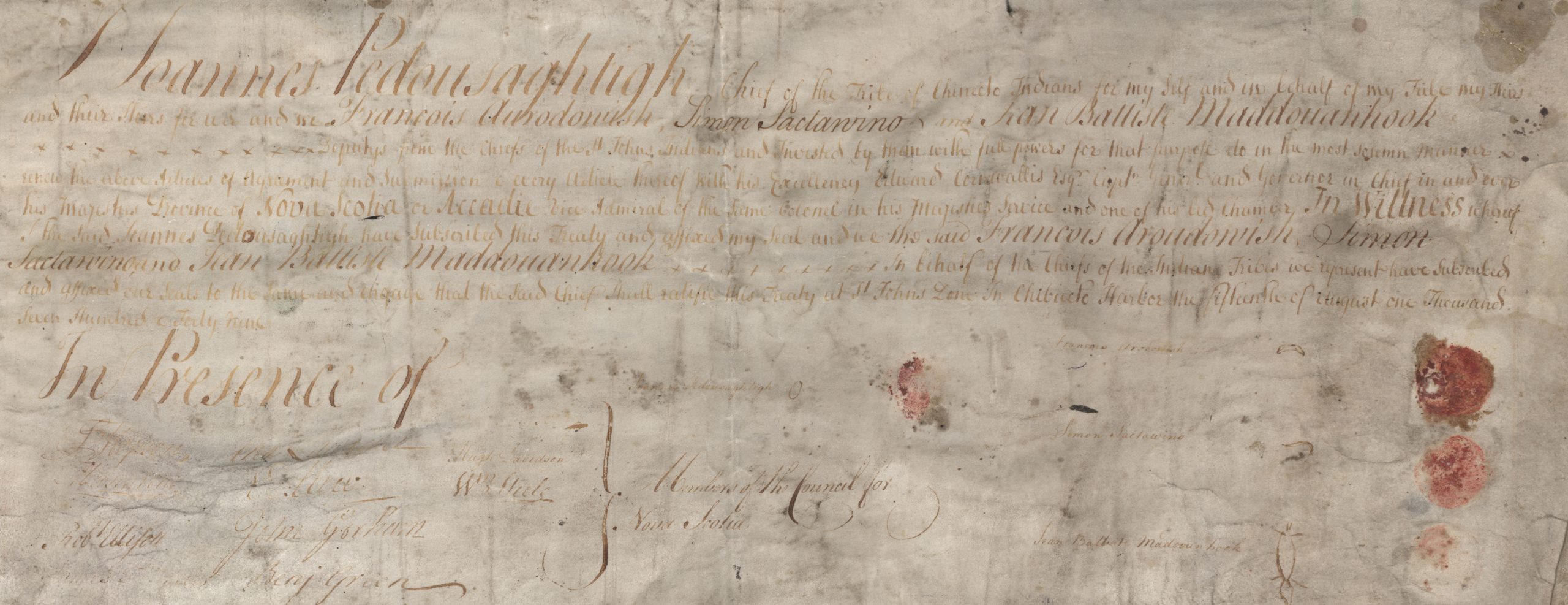

After decades of back-and-forth between French and English claims to Mi’kma’ki, the European geopolitical context changed in 1713. In that year, and 5,000 kilometres away, in the Netherlands, European diplomats came to an agreement that ended the War of Spanish Succession. Though there were no North American diplomats at the meetings that brought about the peace, the resultant Treaty of Utrecht had lasting results in Mi’kma’ki. Just three years before, the British had captured Port Royal (for the fourth time) and – at Utrecht – France and Britain agreed to a division of territory that effectively ripped Mi’kma’ki into two. For the first time since Europeans set foot on Mi’kmaw Homelands, Mi’kma’ki was divided between French and British claims to their Land. The Mi’kmaw regions of Kespukwitk, Sipekne’katik, Eskikewa’kik, and Piktuk were claimed by Britain, while Unama’kik, Epekwitk, Siknikt, and Kespe’k were claimed by France. Despite European agreement about this new geopolitical situation, no one informed the Mi’kmaq. When they learned to what France and Britain had agreed, they were shocked. By what right had the King of France ceded Mi’kma’ki to Britain, they asked.

In this lesson, we will listen to the Mi’kmaq and their Wabanaki allies as they responded to this type of unilateral European action. Though we can assume that there might have been similar tensions before 1713, the small-scale nature of the European presence in Mi’kma’ki meant that evidence of this type of opposition is difficult to find. After this period, with almost every extension of the French or British occupation of Mi’kma’ki, the Mi’kmaq and their allies made their position clear. Listening to their words helps us understand the structures of power at work in the region over the course of the eighteenth century. In their documents we read about how these people envisioned their relationship to the European newcomers, to each other, and to the Land. Though each document was penned by French allies – and have sometimes been dismissed because of this – we see these sources as some of the most direct and clearest articulations of contemporary Indigenous perspectives available to us.

To better understand each of these documents, we are going to return to ArcGIS and ask you to build a storymap that helps interpret how the Mi’kmaq and Wabanaki responded to the Treaty of Utrecht and subsequent British encroachment into Mi’kma’ki. The collected documents will take you from Utrecht and its immediate aftermath through to the founding of Halifax in 1749.

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this lesson, you should be able to:

ArcGIS

One or more interactive elements has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view them online here: https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/digitaldisruptions/?p=50

8

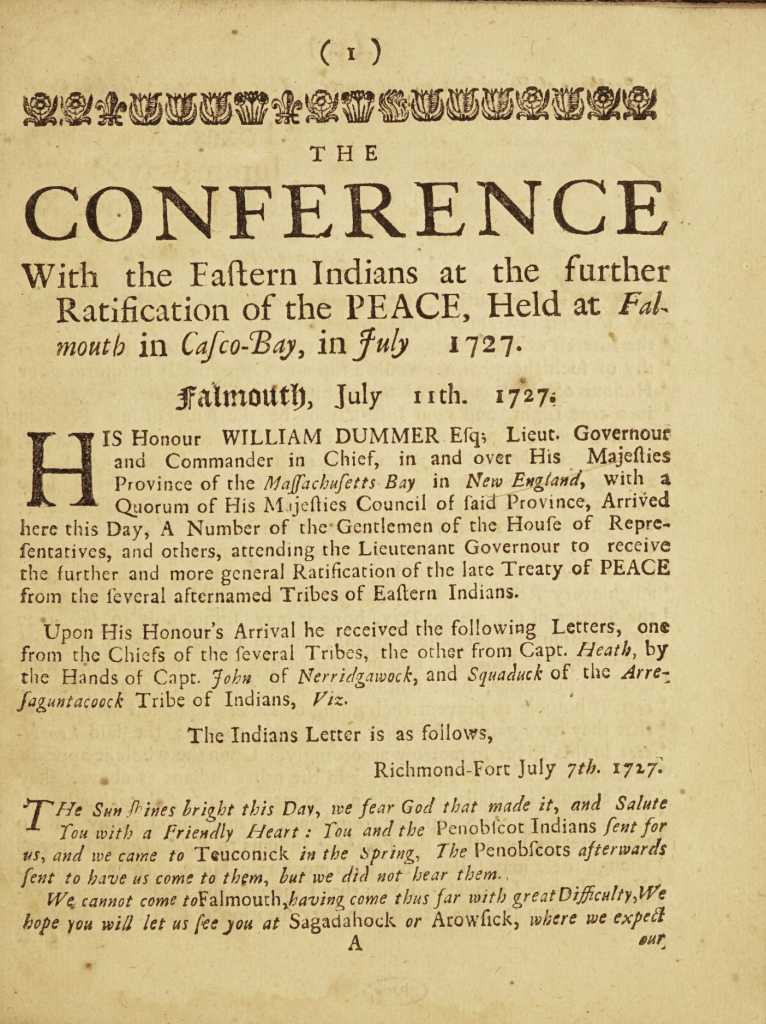

Goal: Comparing Wabanaki- and Mi’kmaw-English/British treaties over time, students will understand the nature of the treaty-making process, its evolution over time, and the changing historical context of those changes. Through this exercise they will develop a lens from which to understand the treaties, and to critically assess the treaty-making process.

All nations are governed by treaties. Most often when we think of treaties we think of those that end wars – a peace treaty – but they can be for trade purposes (as just a few years ago when the United States, Mexico and Canada signed a new trade agreement), basic diplomatic matters such as recognising boundaries, or more complex international agreements on everything from environmental standards to limits on nuclear weapons. While quite different in topic, they impose the same forms of legal obligations on all the signatories. As treaties signed between recognised national groups, Canada’s historic treaties with Indigenous peoples are no different.

Between 1725 and 1761, numerous treaties were signed between Great Britain, or its colonial governments in Boston and Halifax, and the Wabanaki peoples of the northeast. They are called Peace and Friendship treaties. For the British, the treaties sought to pacify the Mi’kmaq, and their Wabanaki allies – all traditional allies of the French – from participating in an on-going series of wars over territory in what is today termed eastern Canada and the northeast of the United States. For the Mi’kmaq, the treaties aimed to restrain British, settler incursions into Mi’kma’ki.

Beginning in the 17th century, Britain signed a number of treaties with Indigenous peoples in what is now the US northeast. The most important of these came in the decade after a major war in the 1760s between Indigenous peoples and two British colonies, Rhode Island and Massachusetts. The biggest of these wars is most commonly called King Philip’s War; it was probably the most destructive war in the colonial era. That war ended in 1678, and peace treaties were signed. But as historian Lisa Brooks explains, that war was primarily caused by aggressive land grabs by Massachusetts settlers. In the years after the peace, those land grabs continued, as the New England colonies expanded north along the coast and inland to the west. That expansion also brought the British colonies into conflict with the French colonies to the north (Canada) and the northeast (Acadia). Much of the period between roughly 1680 and 1760 was dominated by on-going wars in western Europe between its two great powers, Britain and France, and these spilled over in northeastern North America. Thus, the land between British and French settlements, whether by land or by sea, was often a war zone. And that war zone was Wabanaki territory.

In one of those later wars, the one European history calls the War of the Spanish Succession (1701-14 – a long war!), Britain captured Port Royal, the administrative capital of Acadia. And in the subsequent peace treaty, Britain was awarded Acadia. As we’ll see in a few weeks, that simple statement was much messier on the ground than on paper. But among a lot of blurred lines, two things were indisputable. First, that the French Catholic Acadians were now, nominally at least, ruled by Britain. We’ll come back to that issue later. Second, “Acadia”, as we’ve seen, was really a series of small agricultural settlements and even smaller fishing settlements. The territory labelled “Acadie” on European maps was still controlled by the Mi’kmaq and other Wabanaki peoples. It was still Mi’kma’ki. The British hold on Acadie was smaller even than that of the French, and so it was imperative that peace be established with the region’s Indigenous peoples. That meant that if Britain wanted to maintain its very tenuous hold on the peninsula, it would need to negotiate treaties with the Mi’kmaq.

We’ll explore the treaties in three exercises.

First, we’ll examine TWO [??] of the actual treaties, one signed in 1725 and another in 1752, and try to understand exactly what they say. The treaties are fundamentally similar, though not identical, They were signed in different times, by different peoples, under different circumstances. We can, however, see some common patterns and some common principles. And legally they’re all still in force. And so our question then is, what does that mean?

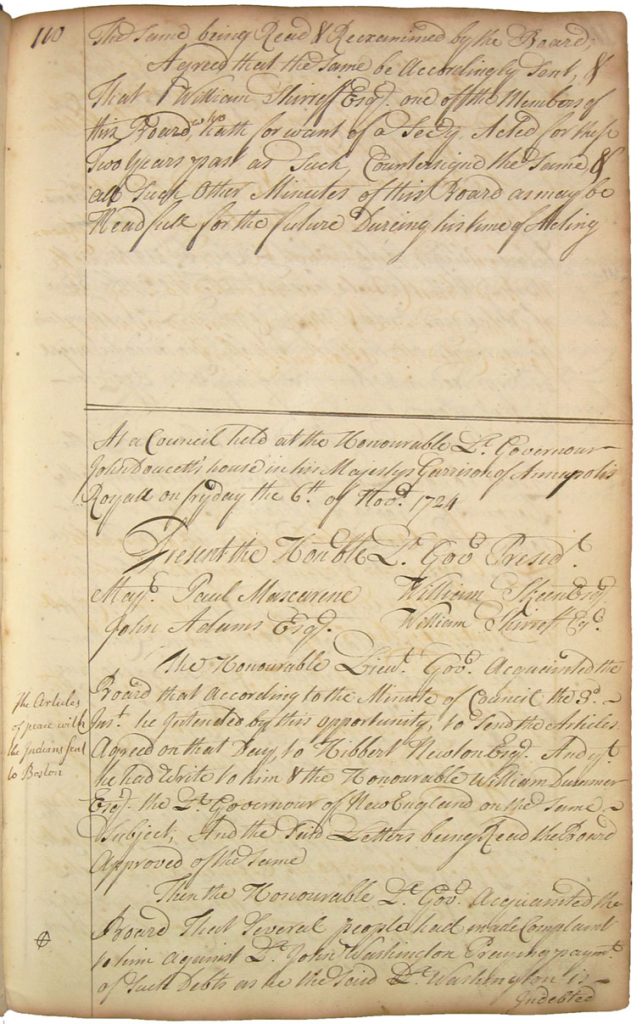

Second, we’ll examine set of records related to the 1725 treaty [BOTH?] and explore the context of the 18th-century colonial-Indigenous treaties as well as the process of making them.

Third, we’ll use Voyant-tools to explore the broader context. Historians are limited by the sources available to them. Most of the documents we’re reading in this lesson come from two sets of records published by archives in Maine and Nova Scotia in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Examining the entire corpus of records, not just the ones we’ve identified as relevant, offers inisghts into the broader historical context and the biases of colonial archives.

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this lesson, you should be able to:

This lesson has three activities.

Activity 1: You’re going to annotate two of the most important treaties signed between the British colonial governments: the Treaty of Boston (1725) and the Treaty of Halifax (1752). Your task here is to understand what the treaties actually say? A treaty is an agreement between two or more people/groups. Does this treaty reflection a conversation? A negotiation? At first glance, the treaties seem fairly clear, pointing to “submission” and other terms suggesting Mi’kmaq surrender. Many of the court cases have turned on whether the treaties were restrictive (limiting what people could do) or positive (enabling activities). Where do you see restrictive or positive language? What kind of treaties are they? Do they end wars? And if so, who won, and what does that mean in the treaties’ terms? Does one side surrender land? Sovereignty? Commit to an alliance? Engage in trade practices?

Using hypothes.is describe and discuss what you see in the treaties and what they appear to mean for the signatories.

Activity 2: The treaties reflect the history and nature of the relationship to that point. What led up to the treaties, the process of actually negotiating the treaties, the difficulties faced negotiating across different languages – indeed, quite different cultures – and the simple problem of getting representative peoples together: all of these factors, and more,

Here you’ll find two sets of documents (one labelled 1725 and the other 1752 [fix “HERE” is only one doc]) related to the negotiations themselves: something of their context (though note we address something of that above in the introduction) and the process by which the treaties were negotiated. One set of documents relates to the 1725 treaty; the other relates to the 1752 treaty. What do these contextual documents tell us about the treaties? Do these change our understanding of the treaties? Do we see evidence of language and cultural challenges? Using hypothes.is annotate one of the two documents. Describe and discuss what you see as evidence that seems important to our understanding of the treaties themselves.

Remember: the Wabanaki are a confederacy, not a nation. Who’s doing the negotiating? How are the other members of the confederacy participating?

Activity 3: Much of the primary source material we use in this course, and all that we use in this lesson, comes not from the original 18th-century documents but from transcriptions made by archives and historical societies in Massachusetts, Nova Scotia, Maine, and Québec. These are fantastic resources and we’re really happy to have them available to us; they make available materials that would otherwise be very inaccessible.

They also provide us with both an opportunity (not just some excerpts here and there, but a substantial body of evidence) and a potential trap (these documents represent selections, what some 19th-century guy [and it was almost invariably, a guy!] chose and edited for us to read). Now, to be clear, we’re not suggesting a conspiracy, just a bias. And if we can identify the bias, and critically evaluate them, we can work within the limits they provide. We can see three fairly obvious potential issues here.

These issues are limits on our research, but they are not insurmountable problems. If we’re aware of those limits, we can think through both the wealth of information still present as well as the absences, and the sometimes misleading details we may encounter.

Thus, in this activity, we ask you to undertake two quick exercises that might allow you to reflect on our sources – the sources we’re using in this course and the wider world of sources. All good historical writing is limited by the quantity and quality of the sources that are available. Here, using Voyant, we’d like you to examine two wider set of documents.

First, use Voyant to read the entire volume of documents from which our excerpts were drawn. Half the documents you’re using are from New England and all these from one volume of a collection produced in the late-19th century by the Maine Historical Society. Find the volume [here] and enter the URL into the search box of Voyant-tools. Make use of some of the simple clean-ups (you’ll certainly see some stop words worth adding), and then examine some of the tools we used in Lesson [TWO??]. Voyant gives us a wider view of data contained in that volume; does it confirm what we’ve been reading as we annotate? Does it suggest other possibilities?

Then follow this link which gives you a page with sixteen URLs, one each to sixteen volumes of the Maine collection. Copy and paste all those URLs (at the same time) into Voyant. You’ll be getting an output of the entire corpus of the Maine Historical Society collections. Are the patterns we saw earlier evident here? Are new themes evident? What does this exercise suggest about the place of settler colonialism in the writing of history in the North American northeast over the past century?

Documents

1725 – one document that combines excerpts from the minutes of meetings of the Massachusetts and the Nova Scotia Legislative Councils, 1724-26.

1752 –

OR (as a third activity or a mini-assignment -= map the movement of messages/belts/communications from Boston to Casco, St. Francis, Annapolis, Cape Sable, Wolastoq.

Instructions:

Documents:

There are several of these, though most are in some way a ratification or extension of the 1725 Treaty of Boston (in fact, several simply reiterate the terms of 1725).

Casco Bay, 1727 – https://archive.org/details/conferencewithea00mass_0/page/n5/mode/2up

Portsmouth, 1714 – discusssion of terms, lots of emphasis on truck-houses and beaver prices – comparing prices at Saco (near Portsmouth), Penobscot (up the cast, near modern-day Bangor), and “Port Royal” [Querrebuit, 167]

Mi’kmaq at Boston, Nov 1725 -this version, from Early American Indian documents : treaties and laws, 1607-1789, specifically notes the Cape Sable Indians” to be present. It comes from CO5 – Tom do you have this?

Structure:

negotiations from Boston, December 1725, Annapolis 1725, Halifax 1762

Activity: Using the Hypothes.is annotation tool students will identify the key components of the treaties and how they changed over time.

Two steps: read a process, annotate // read a treaty, annotate // forum discussion?

V

9

The founding of Halifax marked a radical turn in Mi’kma’ki and Acadie. Before 1749, the British presence on the land was fairly marginal. Though they had begun to push beyond the fortifications at Annapolis Royal, for the most part the region was one defined by the Mi’kmaq and their Acadian neighbours. With the establishment of Halifax at Kjipuktuk in 1749, the British presence became much more ubiquitous and contested. Not only did Britain build a new fort there, but with this imperial investment, they also brought settlers in the hundreds. With Halifax, the British established German speaking Protestants at Lunenburg as well. All told, by 1755 there were as many as 5,000 British settlers now living in the colony.

Halifax is emblematic of broader changes in how Europeans thought about empire. As imperial official encountered growing challenges of managing overseas affairs, imperial policies began to change. There were two key consequences of these changes. First, as we saw with treaties, increasingly imperial decisions were made by people with neither a deep understanding of the local context or on-the-ground relationships, making it easier to implement policies that might harm local communities. Second, both empires were willing to invest in North America in unprecedented ways. To protect its economic interests, for example, France built Louisbourg in Unama’kik, as well as several new fortifications in the Lower Great Lakes and along the Mississippi, connecting its colonies of Canada and Louisiana. France also build a new fort at Beaubassin in 1750, known as Fort Beausejour (depicted above) at Beaubassin.

These changes were part of a military contest that by 1749 had already brought considerable violence to the the region. The War of Austrian Succession yielded significant casualties in Mi’kma’ki. Though warfare really only arrived here in the later years of the war, its impact was significant. The French, with Mi’kmaw, Wabanaki, and Wendat allies attacked Annapolis Royal twice unsuccessfully. In 1747, the had more success in a raid on a British encampment at Grand Pre. This victory was relatively insignificant, however, given that just the year before New Englanders had successfully captured Louisbourg. The French position in the region was weak. With the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle peace returned in early 1748 but the lesson learned on both sides was that Mi’kma’ki needed to be militarized. In addition to building at Beaubassin, France reinvested at Louisbourg and fortified Baie Vert (Fort Gaspereaux) and the mouth of the Saint John River. While the British, in addition to building Halifax, extended its military presence to Piziquid (Fort Edward) and Sackville, and also at Beaubassin. By 1751, France’s Fort Beausejour lay only four kilometers across the Missaguash River from Britain’s Fort Lawrence.

Rather than bringing peace, as all of this fort building attests, it is more accurate to state that the 1748 peace caused a pause in the fighting. By 1754, violence between Britain and France was renewed in the Ohio Country (between the Mississippi and Lake Erie) and shortly thereafter it was sparked again in Mi’kma’ki. Beaubassin was the only place in the world where British and French fortifications were located in such close proximity to each other. Further, despite the growing British Protestant population at Halifax and Lunenburg, the French Catholic Acadian population had topped 15,000 people. British officials with limited relationship to either the Acadians or Mi’kmaq feared that with the French military so close, these people would rise up. With a large population of New Englanders (many who were upset that Britain had returned Louisbourg to France), British officials at Halifax and in Boston planned to seize Fort Beausejour.

The attack came in June 1755 and was over almost as quickly as it had begun. The British capture of Fort Beausejour, however, was only the beginning. In addition to removing the French military threat, British and New England officials quickly sought to solve the Acadian problem that had long been a thorn in the colony’s side. Right from Britain’s initial occupation of the fort at Annapolis, tensions over the loyalty of the Acadian population threatened the region’s stability. At issue was whether this French Catholic population would take an oath of allegiance to the British crown. Though it had festered for decades, British administrators had been willing to compromise until the new regime arrived in 1749. With administrators with limited on-the-ground experience, the issue of loyalty flared up again in the 1750s, specifically in the weeks after Beausejour fell. On July 28, 1755 British officials decided to deport the entire Acadian community. By 1763, when the deportation came to a close, over 15,000 people had been forcibly removed to Britain’s American colonies, England, France, Louisiana, and the Caribbean.

This module will introduce you to several accounts written at Beaubassin during the 1750s. Using the digital tools we have drawn upon in earlier modules, you will form an understanding of the circumstances that led to the Acadian Deportation.

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this lesson, you should be able to:

ArcGIS

Activity 1: Carefully read and annotate (using hypothes.is) one of the assigned documents. Do some research about the author and write a 150 word explanation about how useful this source is for understanding the events that took place at Beaubassin in 1755.

Activity 2: Use Voyant Tools to read all of the assigned documents together. What conclusions can we draw about these events from the information Voyant provides you? Does this analysis align well with the work that you conducted in Activity 1?

Activity 3: Use the information that you have learned from Activities 1 and 2, as well as the map included with the documents below, to create a sketch layer in ARCgis online that will help students better understand what took place at Beaubassin in the summer of 1755.

10

Having expelled most Acadian settlers in 1755 and 1758 and negotiated a series of treaties Mi’kmaw and Wabanaki nations, Britain and its colonial officials in Boston and Halifax set about efforts to remake the colony as an Anglo-American place. From a British-New England perspective, they now had a blank slate upon which they could write as they pleased. Part of that process occurred through measured state-led endeavours to properly administer settlement and proper government; part of it was a land grab, a period one notable historian describes as a series of “wild schemes, conflicting claims, and unfulfillable promises that actually hindered the colony’s recovery from the devastations of war and depopulation” [Anderson, CoW, 523]. In many ways it was both.

Though small compared to the rapidly growing New England colonies, Acadians had built a series of successful agricultural settlements. Acadian farms regularly produced surpluses of cattle and wheat that found a ready market in Annapolis Royal and Boston, and from a British perspective more problematically in Louisbourg and Quebec. That made these lands attractive. Knowledge of this was widespread and in fact was one of the reasons the British never pushed hard for the removal of the Acadians after 1713: they knew Acadian crops were vital supports for the feeding the fishery and the military. As we’ve seen, that thinking changed, and now imperial and colonial planners set about putting a British stamp on Mi’kma’ki/Acadie.

One of the most important of these British planners was Charles Morris, a Boston-born army officer who was stationed at Annapolis Royal, and in 1750 was appointed Crown surveyor for the province. His reports and maps outline many of the specific actions that would unfold over the next decade, as well as the general views of British officials in acquired territories. Morris was one of the architects of the expulsion of the Acadians. In a series of reports written between 1749 and 1755, he outlined various schemes for marginalising the Acadians (mostly swamping them with British, New England, Swiss and German Protestant settlers), and renaming places: the Acadian village of Beaubassin became Sackville; the Mi’kmaw settlement of Mirligueche became Lunenburg, and they would be populated not with “Indians” and French Catholics but European Protestants. He quickly shifted his position, however, to simply removing the French Catholics who had farmed those lands for three, sometimes four generations. His 1755 map of the French settlements was very much a tool of identifying the major and minor Acadian settlements and how best to organize their removal. By that point he had become one of the most influential figures in Boston and Halifax. The Surveyor-General had become the most knowledgeable Briton alive on the geography of the province; that knowledge would now allow him to be the principal architect remaking Acadie into Nova Scotia.

This lesson asks you to examine texts and maps related planning Nova Scotia after the Seven Years War. In Acadie/Mi’kma’ki that language, and indeed the story itself, is tricky because it’s not simply European colonizers displacing Indigenous peoples, but of one set of European colonizers dispossessing Indigenous peoples and another set of European colonizers – and this latter group was not an army, but several thousand farmers who had occupied their lands for generations. The relationship between the Acadians and the Mi’kmaw was not the happy to co-existence often presented mythic description of Acadia, but at minimum they had spent decades sharing space without large-scale conflicts and had come to share a common enemy. We can’t explore that relationship in this lesson, but we can explore how the Anglo-Americans saw the the two groups and how they planned for their removal.

These documents will allow you to see the strategies employed by the mapmakers, their aims and how the maps were designed to both reflect existing policy and to envision new approaches and possibilities. In exploring the production of maps, this exercise will enable you to better understand the language and strategy of mapping and its role in turning Mi’kma’ki/Acadie into British Nova Scotia.

LEARNING OUTCOMES

By the end of this lesson you should be able to:

Hypothes.is