Literature Review – More Resources to Keep You Going

47

How to Conduct a Literature Review

Aveyard, H. (2019). Doing a literature review in health and social care: A practical guide (Fourth ed.) Open University Press, McGraw-Hill Education.

Jesson, J., Matheson, L., & Lacey, F. M. (2011). Doing your literature review: Traditional and systematic techniques. SAGE.

Ridley, D., Dr. (2008). The literature review: A step-by-step guide for students. SAGE.

Websites

Constructing a Research Question

Alvesson, M., & Sandberg, J. (2013). Constructing research questions: Doing interesting research. SAGE.

DeCarlo, M (2018) Chapter 8: Creating and refining a research question in Scientific Inquiry in Social Work. Open Social Work Education. https://scientificinquiryinsocialwork.pressbooks.com/

Denney, A. S., & Tewksbury, R. (2013). How to Write a Literature Review. Journal of Criminal Justice Education, 24(2), 218–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511253.2012.730617

How to Search

Videos

The National Library of Medicine (2013, February 14). Use MeSH to Build a Better PubMed Query [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uyF8uQY9wys

UTS Library (2021, February 23). Medline Ovid: Advanced Searching [Video]. YouTube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6QQ0MW_jXfM

Websites

Reading Strategies

Greenhalgh T. (1997). How to read a paper. Getting your bearings (deciding what the paper is about). BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 315(7102), 243–246. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.315.7102.243

Sweeney, M. “How to Read for Grad School.” Miriam E. Sweeney, 20 June 2012, https://miriamsweeney.net/2012/06/20/readforgradschool/.

Quality Assessment

Greenhalgh T. (1997). Assessing the methodological quality of published papers. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 315(7103), 305–308. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.315.7103.305

Greenhalgh, T., & Taylor, R. (1997). Papers that go beyond numbers (qualitative research). BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 315(7110), 740–743. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.315.7110.740

Checklists and Tools

Writing

Allen, J. (2019). The productive graduate student writer: How to manage your time, process, and energy to write your research proposal, thesis, and dissertation, and get published (First ed.). Stylus Publishing, LLC.

Denney, A. S., & Tewksbury, R. (2013). How to Write a Literature Review. Journal of Criminal Justice Education, 24(2), 218–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511253.2012.730617

Feak, C. B., & Swales, J. M. (2009). Telling a research story: Writing a literature review. University of Michigan Press.

Holland, K., & Watson, R. (2021). Writing for publication in nursing and healthcare: Getting it right (Second;2; ed.). John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

Walliman, N. (2006). Writing a literature review. In Social research methods (pp. 182-185). SAGE Publications, Ltd,

Website

Official Citation Manuels

APA

American Psychological Association (2020). Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association: The official guide to APA style (Seventh ed.). American Psychological Association.

MLA

Modern Language Association of America. (2021). MLA handbook (Ninth ed.). Modern Language Association of America.

Turabian (Chicago)

Turabian, Booth, W. C., Colomb, G. G., & Williams, J. M. (2018). Manual for Writers of Research Papers, Theses, and Dissertations (9th edition.). University of Chicago Press.

IEEE

IEEE (n.d). IEEE Reference Guide. https://ieeeauthorcenter.ieee.org/wp-content/uploads/IEEE-Reference-Guide.pdf

Vancouver or ICMJE

International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. (2021, December). Recommendations for the Conduct, Reporting, Editing, and Publication of Scholarly Work in Medical Journals. http://www.icmje.org/icmje-recommendations.pdf

Systematic Review – More Resources to Keep You Going

48

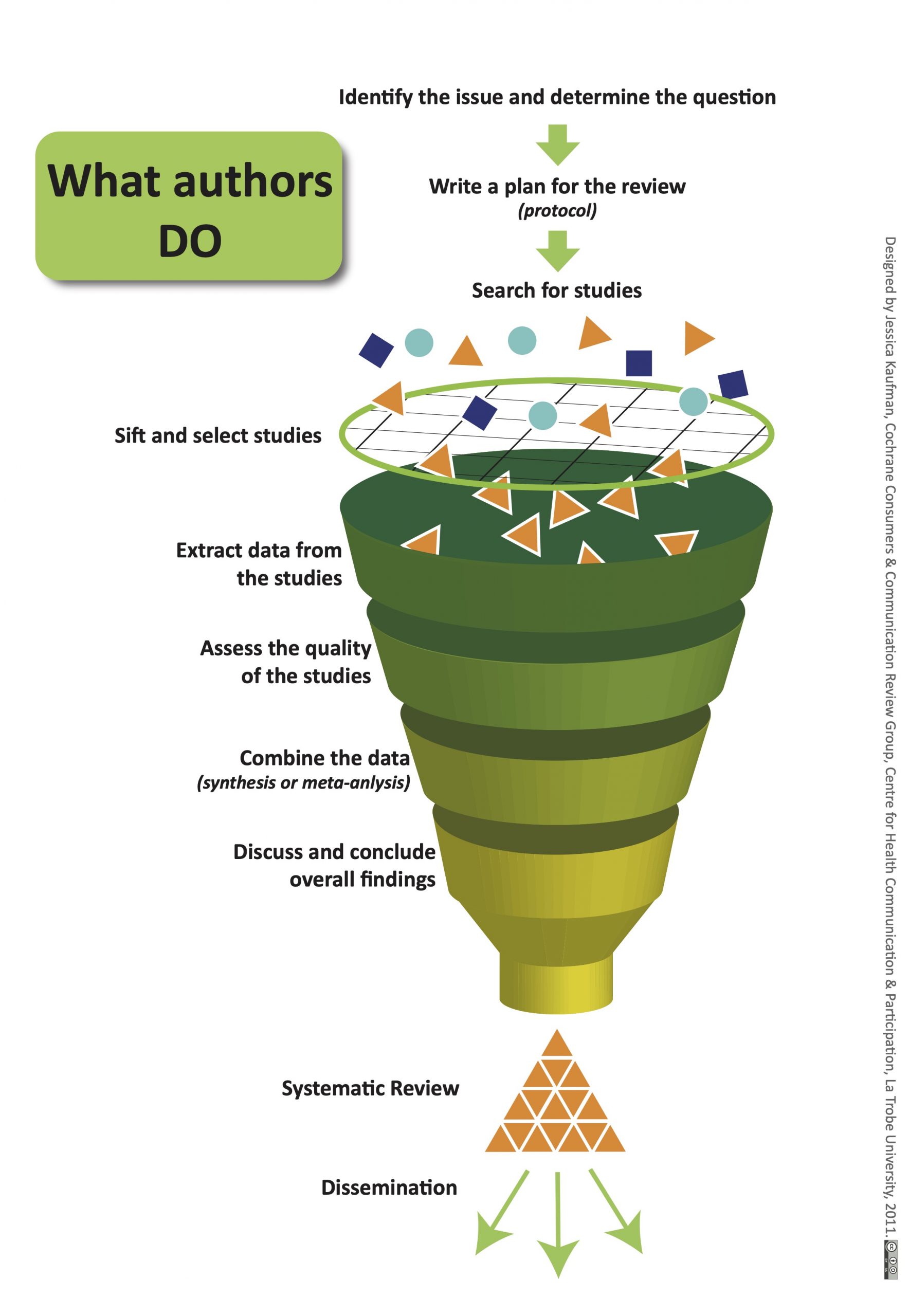

How to Conduct a Systematic Review

Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19-32. doi:10.1080/1364557032000119616

Boland, A., Cherry, M. G., & Dickson, R. (2014). Doing a systematic review: A student’s guide. SAGE.

Ganann, R., Ciliska, D., & Thomas, H. (2010). Expediting systematic reviews: Methods and implications of rapid reviews. Implementation Science, 5(1), 56-56. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-5-56

Glass, G. (1976). Primary, Secondary, and Meta-Analysis of Research. Educational Researcher, 5(10), 3-8. doi:10.2307/1174772

Gough, D., & Richardson, M. (2018). Systematic reviews. In Advanced research methods for applied psychology (pp. 63-75). Routledge.

Grant, M. J., & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health information & Libraries Journal, 26(2), 91-108. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

Higgins J.P.T, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page M.J, Welch V.A. (Eds). (2021, February). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.2. Cochrane. www.training.cochrane.org/handbook.

Websites

Online Courses on Systematic Reviews

The following guide provides a list of online self-directed learning on how to conduct a systematic review

Online Courses on Systematic Reviews (St. Michael’s Hospital Health Science Library)

Registering Your Systematic Review

Creating Your Protocol

Documenting Your Review with PRISMA

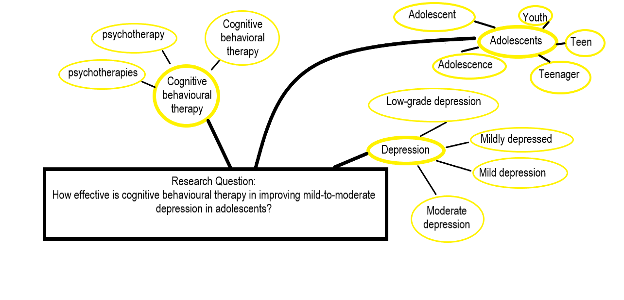

Constructing a Research Question

Alvesson, M., & Sandberg, J. (2013). Constructing research questions: Doing interesting research. SAGE.

Boland, A., Cherry, M. G., & Dickson, R. (2017). Chapter 3 in Doing a systematic review: A student’s guide (Second ed.). SAGE.

DeCarlo, M (2018) Chapter 8: Creating and refining a research question in Scientific Inquiry in Social Work. Open Social Work Education. https://scientificinquiryinsocialwork.pressbooks.com/

Denney, A. S., & Tewksbury, R. (2013). How to Write a Literature Review. Journal of Criminal Justice Education, 24(2), 218–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511253.2012.730617

Thomas J, Kneale D, McKenzie JE, Brennan SE, Bhaumik S. (2021, February). Chapter 2: Determining the scope of the review and the questions it will address. In Higgins J.P.T, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page M.J, Welch V.A. (Eds). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.2. Cochrane. https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current/chapter-02

How to Search

Lefebvre C, Glanville J, Briscoe S, Littlewood A, Marshall C, Metzendorf M-I, Noel-Storr A, Rader T, Shokraneh F, Thomas J, Wieland LS. (2021, February). Chapter 4: Searching for and selecting studies.In Higgins J.P.T, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page M.J, Welch V.A. (Eds). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.2. Cochrane. https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current/chapter-04

Sayers, A. (2008). Tips and tricks in performing a systematic review. British Journal of General Practice, 58(547), 136-136. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2151802/

CADTH Search Filters Database: https://searchfilters.cadth.ca/

Videos

Websites

Screening

Lefebvre C, Glanville J, Briscoe S, Littlewood A, Marshall C, Metzendorf M-I, Noel-Storr A, Rader T, Shokraneh F, Thomas J, Wieland LS. (2021, February). Chapter 4: Searching for and selecting studies. In Higgins J.P.T, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page M.J, Welch V.A. (Eds). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.2. Cochrane. https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current/chapter-04

(see See section 4.6 Selecting Studies)

Reading Strategies

Greenhalgh T. (1997). How to read a paper. Getting your bearings (deciding what the paper is about). BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 315(7102), 243–246. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.315.7102.243

Sweeney, M. “How to Read for Grad School.” Miriam E. Sweeney, 20 June 2012, https://miriamsweeney.net/2012/06/20/readforgradschool/.

Bias and Quality Assessment

Boutron I, Page MJ, Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Lundh A, Hróbjartsson A. (2021, February). Chapter 7: Considering bias and conflicts of interest among the included studies. In Higgins J.P.T, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page M.J, Welch V.A. (Eds). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.2. Cochrane. https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current/chapter-07

Greenhalgh T. (1997). Assessing the methodological quality of published papers. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 315(7103), 305–308. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.315.7103.305

Greenhalgh, T., & Taylor, R. (1997). Papers that go beyond numbers (qualitative research). BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 315(7110), 740–743. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.315.7110.740

Keenan, C. (2018, April 18). Assessing and addressing bias in systematic reviews. Meta-Evidence Blog, Campbell Collaboration, UK & Ireland. http://meta-evidence.co.uk/assessing-and-addressing-bias-in-systematic-reviews/

Checklists and Tools for Quality Assessment

Websites for Quality Assessment

Tools for Assessing Bias

- ROBIS – A tool for assessing the risk of bias in systematic reviews

- AMSTAR2 – AMSTAR stands for A MeaSurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews.

Analyzing Data

Card, N. A., & Little, T. D. (2012). Applied meta-analysis for social science research. Guilford Press.

Cheung, M. W. -., & Vijayakumar, R. (2016). A guide to conducting a meta-analysis. Neuropsychology Review, 26(2), 121-128. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11065-016-9319-z

Li T, Higgins JPT, Deeks JJ (editors). Chapter 5: Collecting data. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.2 (updated February 2021). Cochrane, 2021. https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current/chapter-05

Writing

Allen, J. (2019). The productive graduate student writer: How to manage your time, process, and energy to write your research proposal, thesis, and dissertation, and get published (First ed.). Stylus Publishing, LLC.

Holland, K., & Watson, R. (2021). Writing for publication in nursing and healthcare: Getting it right (Second;2; ed.). John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

Boland, A., Cherry, M. G., & Dickson, R. (2014). Doing a systematic review: A student’s guide. SAGE.

Official Citation Manuels

APA

American Psychological Association (2020). Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association: The official guide to APA style (Seventh ed.). American Psychological Association.

MLA

Modern Language Association of America. (2021). MLA handbook (Ninth ed.). Modern Language Association of America.

Turabian (Chicago)

Turabian, Booth, W. C., Colomb, G. G., & Williams, J. M. (2018). Manual for Writers of Research Papers, Theses, and Dissertations (9th edition.). University of Chicago Press.

IEEE

IEEE (n.d). IEEE Reference Guide. https://ieeeauthorcenter.ieee.org/wp-content/uploads/IEEE-Reference-Guide.pdf

Vancouver or ICMJE

International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. (2021, December). Recommendations for the Conduct, Reporting, Editing, and Publication of Scholarly Work in Medical Journals. http://www.icmje.org/icmje-recommendations.pdf