One or more interactive elements has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view them online here: https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/studyprocaff2/?p=95#oembed-6

This section examines a wide range of topics, from nutrition, exercise, and sleep to substance abuse and risks related to sexual activity. All of these involve personal attitudes and behaviors. Paying attention to your eating, sleeping and exercise habits becomes more vital when attending college because learning is challenging. However, time pressures, schedule changes and new responsibilities can throw students off their previous routines.

Photo by Jason Wong on Unsplash

Consider your present knowledge and attitudes with the following statements. Consider how true these statements are for you:

Yes Unsure No

1. I usually eat well and maintain my weight at an appropriate level.

2. I get enough regular exercise to consider myself healthy.

3. I get enough restful sleep and feel alert throughout the day.

4. My attitudes and habits involving smoking, alcohol, and drugs are beneficial to my health.

5. I am coping in a healthy way with the everyday stresses of being a student.

6. I am generally a happy person.

7. I am comfortable with my sexual values and my knowledge of safe sex practices.

8. I understand how all of these different health factors interrelate and affect my academic success as a student.

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/studyprocaff2/?p=95#h5p-17

Health and wellness are important for everyone—students included. Not only will you do better in school when your health is good, but you’ll be happier as a person. And the habits you develop now will likely persist for years to come. That means that what you’re doing now in terms of personal health will have a huge influence on your health throughout life and can help you avoid many serious diseases. Considerable research has demonstrated that the basic elements of good health—nutrition, exercise, not abusing substances, stress reduction—are important for preventing disease. You’ll live much longer and happier than someone without good habits.

Here are a few of the health problems whose risks can be lowered by healthful habits:

- Cardiovascular issues such as heart attacks and strokes (the numbers one and three causes of death)

- Some cancers

- Diabetes (currently reaching epidemic proportions)

- Lung diseases related to smoking

- Injuries related to substance abuse

Wellness is more than just avoiding disease. Wellness involves feeling good in every respect, in mind and spirit as well as in body.

Good health habits also offer these benefits for your college career:

- More energy

- Better ability to focus on your studies

- Less stress, feeling more resilient and able to handle day-to-day stress

- Less time lost to colds, flu, infections, and other illnesses

- More restful sleep

One or more interactive elements has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view them online here: https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/studyprocaff2/?p=95#oembed-7

Eating Well: It’s Not So Difficult

Image by Jasmine Lin from Pixabay

The key to a good diet is to eat a varied diet with lots of vegetables, fruits, and whole grains and to minimize fats, sugar, and salt. The exact amounts depend on your calorie requirements and activity levels, but you don’t have to count calories or measure and weigh your food to eat well.

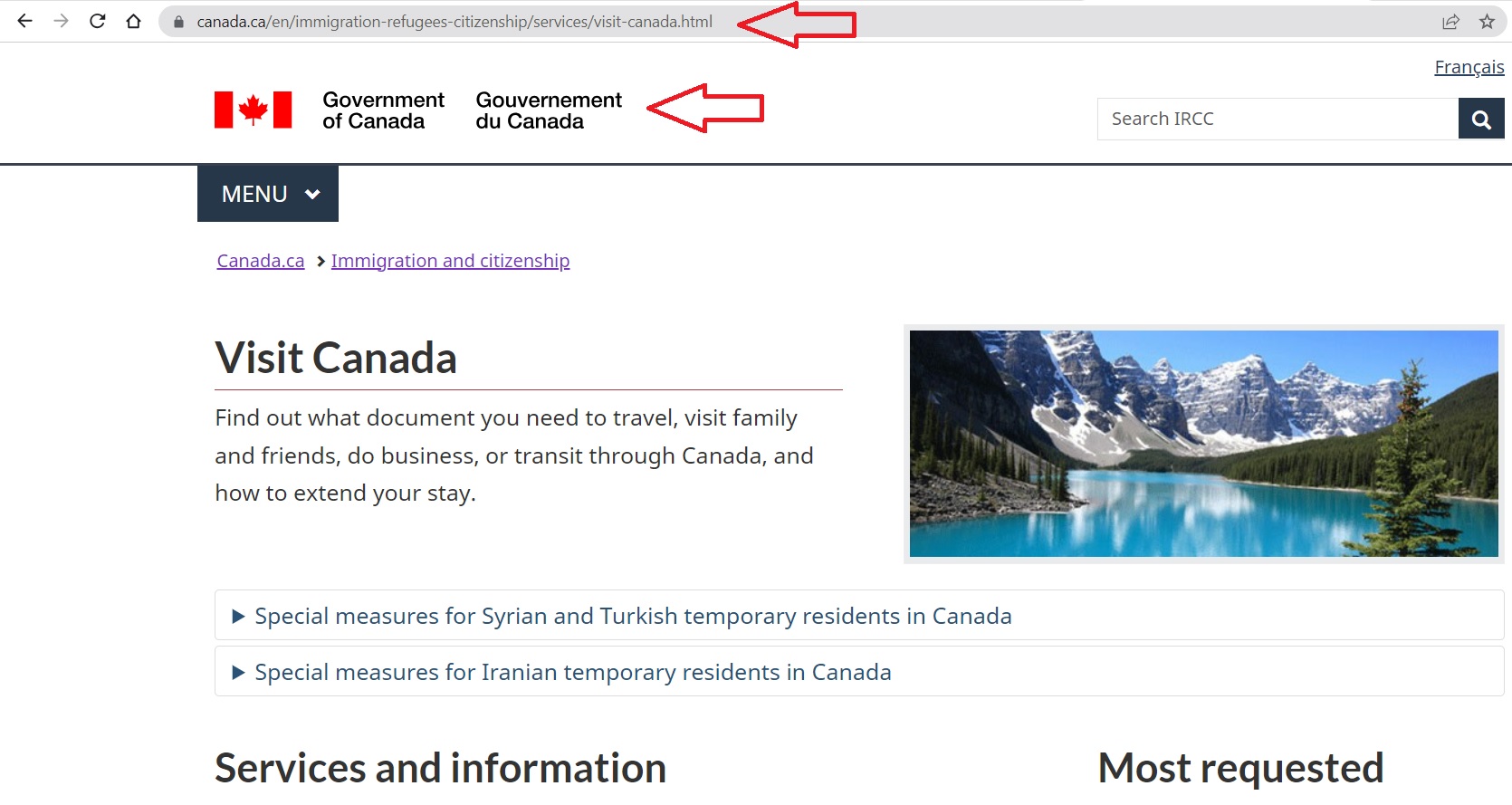

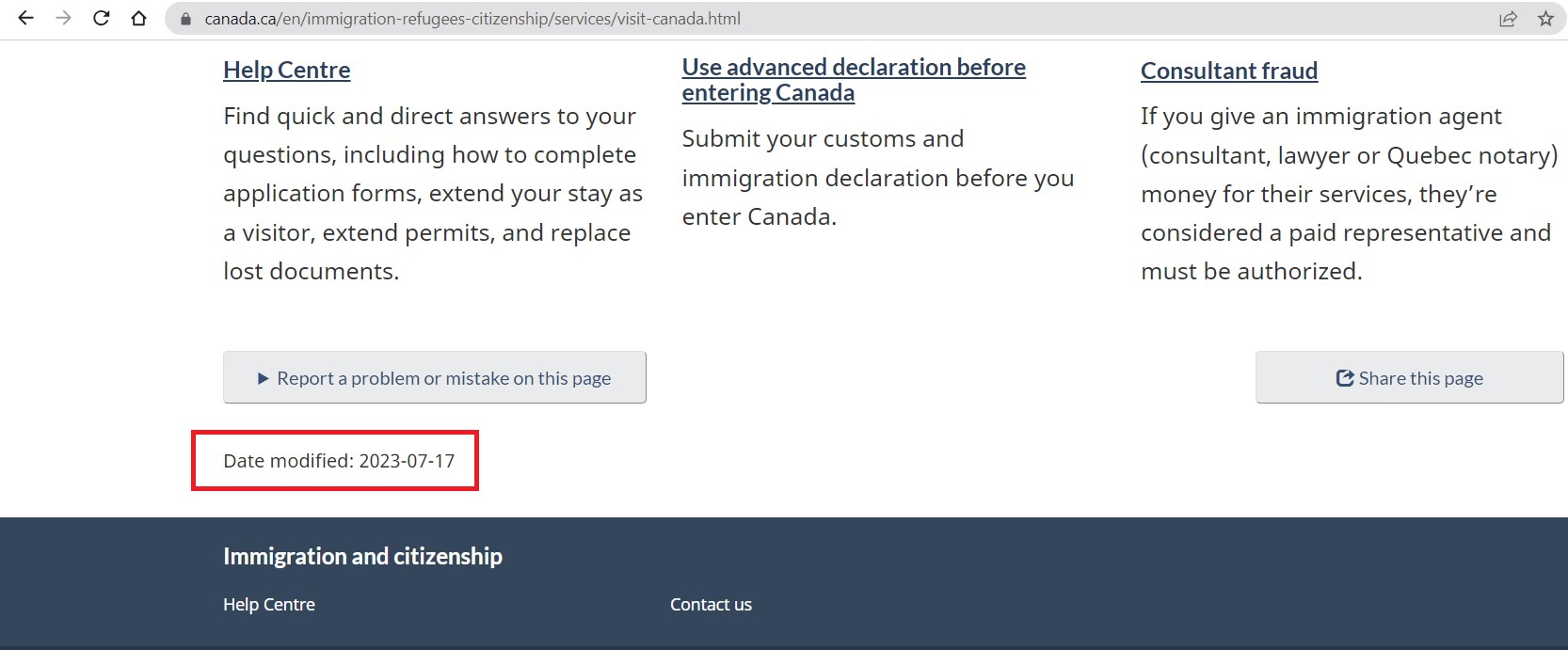

The following is from the Health Canada’s (2022) Food Guide:

Healthy eating is more than the foods you eat. It is also about where, when, why and how you eat.

Be mindful of your eating habits

- Take time to eat

- Notice when you are hungry and when you are full

Cook more often

- Plan what you eat

- Involve others in planning and preparing meals

Enjoy your food

- Culture and food traditions can be a part of healthy eating

- Eat meals with others

Make it a habit to eat a variety of healthy foods each day.

Eat plenty of vegetables and fruits, whole grain foods and protein foods. Choose protein foods that come from plants more often.

- Choose foods with healthy fats instead of saturated fat

Limit highly processed foods. If you choose these foods, eat them less often and in small amounts.

- Prepare meals and snacks using ingredients that have little to no added sodium, sugars or saturated fat

- Choose healthier menu options when eating out

Make water your drink of choice

- Replace sugary drinks with water

Use food labels

- Be aware that food marketing can influence your choices

If You Need to Lose Weight

Image by Total Shape from Unsplash

If you need to lose weight, don’t try to starve yourself. Gradual steady weight loss is healthier and easier. Try these guidelines:

- Check your body mass index (BMI) to see the normal weight range for your height.

- Set your goals and make a plan you can live with. Start by avoiding snacks and fast foods.

- Try to choose foods that meet the guidelines listed above.

- Stay active and try to exercise frequently.

- Keep a daily food journal and write down what you eat. Simply writing it down helps people.

- Be more aware of your habits, and more motivated to eat better.

- Visit Health Services on campus and ask for more information about weight loss programs.

Remember, no single plan works for everyone.

Tips for Success: Nutrition

Photo by Anna Pelzer from Unsplash

- Eat a variety of foods every day.

- Take a multivitamin every day.

- Take an apple or banana with you for a snack in case you get hungry between meals.

- Avoid fried foods.

- Avoid high-sugar foods. After the rush comes a crash that can make you drowsy, and you’ll have trouble paying attention in class. Watch out for sugary cereals—try other types with less sugar and more fiber.

- If you have a soft drink habit, experiment with flavored seltzer and other zero- or low-calorie drinks.

- Eat when you’re hungry, not when you’re bored or just because others are eating.

- If you find yourself in a fast food restaurant, try a salad.

- Watch portion sizes and never “supersize it”!

Does Exercise Really Matter?

Exercise is good for both body and mind. Indeed, physical activity is almost essential for good health and student success.

The physical benefits of regular exercise include the following:

Photo by Trust “Tru” Katsande on Unsplash

- Improved fitness for the whole body, not just the muscles

- Greater cardiovascular fitness and reduced disease risk

- Increased physical endurance

- Stronger immune system, providing more resistance to disease

- Lower cholesterol levels, reducing the risks of cardiovascular disease

- Lowered risk of developing diabetes

- Weight maintenance or loss

Perhaps more important to students are the mental and psychological benefits:

- Stress reduction

- Improved mood, with less anxiety and depression

- Improved ability to focus mentally

- Better sleep

- Feeling better about oneself

For all of these reasons, it’s important for college students to regularly exercise or engage in physical activity. Like good nutrition and getting enough sleep, exercise is a key habit that contributes to overall wellness that promotes college success.

How Much Exercise and What Kind?

With aerobic exercise, your heart and lungs are working hard enough to improve your cardiovascular fitness. This generally means moving fast enough to increase your heart rate and breathing. For health and stress-reducing benefits, try to exercise at least three days a week for at least twenty to thirty minutes at a time. If you really enjoy exercise and are motivated, you may exercise as often as six days a week, but take at least one day of rest. When you’re first starting out, or if you’ve been inactive for a while, take it gradually, and let your body adjust between sessions. But the old expression “No pain, no gain” is not true, regardless of what some past gym teacher may have said! If you feel pain in any activity, stop or cut back.

The way to build up strength and endurance is through a plan that is consistent and gradual. For exercise to have aerobic benefits, try to keep your heart rate in the target heart rate zone for at least twenty to thirty minutes. The target heart rate is 60 percent to 85 percent of your maximum heart rate, which can be calculated as 220 minus your age. For example, if you are 24 years old, your maximum heart rate is calculated as 196, and your target heart rate is 118 to 166 beats per minute. If you are just starting an exercise program, stay at the lower end of this range and gradually work up over a few weeks.

Enjoy It!

Photo by Matthew LeJune on Unsplash

Most important, find a type of exercise or activity that you enjoy—or else you won’t stick with it. This can be as simple and easy as a brisk walk or slow jog through a park or across campus. Swimming is excellent exercise, but so is dancing. Think about what you like to do and explore activities that provide exercise while you’re having fun.

Do whatever you need to make your chosen activity enjoyable. Many people listen to music and some even read when using workout equipment. Try different activities to prevent boredom. You also gain by taking the stairs instead of elevators, walking farther across campus instead of parking as close to your destination as you can get, and so on. Exercise with a friend is more enjoyable, including jogging or biking together.

You may stay more motivated using exercise equipment. An inexpensive pedometer can track your progress walking or jogging, or a bike computer can monitor your speed and time. A heart rate monitor makes it easy to stay in your target zone; many models also calculate calories burned. Some devices can input your exercise into your computer to track your progress and make a chart of your improvements.

The biggest obstacle to getting enough exercise, many students say, is a lack of time. Actually, we all have the time, if we manage it well. Build exercise into your weekly schedule on selected days. Eventually you’ll find that regular exercise actually saves you time because you’re sleeping better and concentrating better. Time you used to fritter away is now used for activity that provides many benefits.

Campus Activities Can Help

Colleges have resources to make exercise easier and more enjoyable for our students. Take a look around and think about what you might enjoy. Campus fitness centers may offer exercise equipment. There may be regularly scheduled aerobic or spin classes. You don’t have to be an athlete to enjoy casual sports such as playing tennis or shooting hoops with a friend. If you like more organized team sports, try intramural sports.

While there are many online exercise videos available that you can do from home, we wanted to share a few of our favorites.

ParticipACTION

Since 1971,

ParticipACTION has been a Canadian institution promoting fitness and exercise to Canadian to get us all moving. Their website has tips, resources and ideas on how to get up and get going!

Take a quick break right now and get fit while you sit!

Healthier. Happier.

From the Queenland government:

Healthier. Happier. These exercises are sorted in different groups including beginner, gentle, moderate and intense. Each exercise includes clear step-by-step instructions and video demonstration.

- Let’s Get Started Beginner’s workout is a great place to… get started!

- The No Sweat Lunch Break is a straightforward exercise routine that can easily be done at home with no special equipment. The web page explains each exercise that then can be combined into the routine in the video.

Do Yoga With Me

Do Yoga With Me is a popular Youtube channel with a variety of yoga video for people at all levels of yoga experience. One special feature is the video for children. (By the way, the kid’s yoga videos are pretty fun to do as an adult too.)

One or more interactive elements has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view them online here: https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/studyprocaff2/?p=95#oembed-9

Like good nutrition and exercise, adequate sleep is crucial for wellness and success. Sleep is particularly important for students because there seem to be so many time pressures—to attend class, study, maintain a social life, and perhaps work—that most college students have difficulty getting enough. Yet sleep is critical for concentrating well.

The Importance of a Good Night’s Sleep

You may not realize the benefits of sleep, or the problems associated with being sleep deprived, because most likely you’ve had the same sleep habits for a long time. Or maybe you know you’re getting less sleep now, but with all the changes in your life, how can you tell if some of your stress or problems studying are related to not enough sleep?

It is recommended by The National Sleep Foundation that young adults get between 7 and 9 hours of sleep per night. Lack of sleep can contribute to difficulty in learning as it may cause impaired cognitive functioning, impaired alertness and lead to longer term health difficulties. We may take sleep for granted and never really think about what helps us get a good nights’ rest. Sleep hygiene is one way to help a student towards getting restorative, quality sleep.

Photo by Kate Stone Matheson on Unsplash

On the positive side, a healthy amount of sleep has the following benefits:

- Improves your mood during the day

- Improves your memory and learning abilities

- Gives you more energy

- Strengthens your immune system

- Promotes wellness of body, mind, and spirit

In contrast, not getting enough sleep over time can lead to a wide range of health issues and student problems.

Sleep deprivation can have the following consequences:

- Affects mental health and contributes to stress and feelings of anxiety, depression, and general unhappiness

- Causes sleepiness, difficulty paying attention in class, and ineffective studying

- Weakens the immune system, making it more likely to catch colds and other infections

- Increases the risk of accidents (such as while driving)

- Contributes to weight gain

How much Sleep is enough?

Image by Mpho Mojapelo from Unsplash

College students are the most sleep-deprived population group in the country. With so much to do, who has time for sleep?

Most people need seven to nine hours of sleep a night, and the average is around eight. Some say they need much less than that, but often their behavior during the day shows they are actually sleep deprived. Some genuinely need only about six hours a night. New research indicates there may be a “sleep gene” that determines how much sleep a person needs. So how much sleep do you actually need?

There is no simple answer, in part because the quality of sleep is just as important as the number of hours a person sleeps. Sleeping fitfully for nine hours and waking during the night is usually worse than seven or eight hours of good sleep, so you can’t simply count the hours. Do you usually feel rested and alert all day long? Do you rise from bed easily in the morning without struggling with the alarm clock? Do you have no trouble paying attention to your professors and never feel sleepy in a lecture class? Are you not continually driven to drink more coffee or caffeine-heavy “power drinks” to stay attentive? Are you able to get through work without feeling exhausted? If you answered yes to all of these, you likely are in that 10 percent to 15 percent of college students who consistently get enough sleep.

How to Get More and Better Sleep

Photo by David Clode from Unsplash

You have to allow yourself enough time for a good night’s sleep. Using time management strategies and schedule at least eight hours for sleeping every night. If you still don’t feel alert and energetic during the day, try increasing this to nine hours. Keep a sleep journal, and within a couple weeks you’ll know how much sleep you need and will be on the road to making new habits to ensure you get it.

Myths about Sleep

- Having a drink or two helps me get to sleep better. False: Although you may seem to fall asleep more quickly, alcohol makes sleep less restful, and you’re more likely to awake in the night.

- Exercise before bedtime is good for sleeping. False: Exercise wakes up your body, and it may be some time before you unwind and relax. Exercise earlier in the day, however, is beneficial for sleep.

- It helps to fall asleep after watching television or surfing the Web in bed. False: Rather than helping you unwind, these activities can engage your mind and make it more difficult to get to sleep.

Facts about Sleep

- Avoid nicotine, which can keep you awake—yet another reason to stop smoking.

- Avoid caffeine for six to eight hours before bed. Caffeine remains in the body for three to five hours on the average, much longer for some people. Remember that many soft drinks contain caffeine.

- Don’t eat in the two to three hours before bed. Avoid alcohol before bedtime.

- Don’t nap during the day. Napping is the least productive form of rest and often makes you less alert. It may also prevent you from getting a good night’s sleep.

- Exercise earlier in the day (at least several hours before bedtime).

- Try to get to bed and wake about the same time every day—your body likes a routine.

- Make sure the environment is conducive to sleep: dark, quiet, comfortable, and cool.

- Use your bed only for sleeping, not for studying, watching television, or other activities. Going to bed will become associated with going to sleep.

- Establish a presleep winding-down routine, such as taking a hot bath, listening to soothing music, or reading (not a textbook). If you can’t fall asleep after ten to fifteen minutes in bed, it’s better to get up and do something else rather than lie there fitfully for hours. Do something you find restful (or boring). Read, or listen to a recorded book. Go back to bed when you’re sleepy.

If you frequently cannot get to sleep or are often awake for a long time during the night, you may be suffering from insomnia, a medical condition. Resist the temptation to try over-the-counter sleep aids. If you have tried the tips listed here and still cannot sleep, talk with your health-care provider or visit the student health clinic. Many remedies are available for those with a true sleep problem.

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/studyprocaff2/?p=95#h5p-18

Substances, any kind of drug , have effects on the body and mind. People use these substances for their effects. But many substances have negative effects, including being physically or psychologically addictive. What is important with any substance is to be aware of its effects on your health and on your life as a student, and to make smart choices. Use of any substance to the extent that it has negative effects is generally considered abuse.

Smoking and Tobacco: Why Start, and Why Is It So Hard to Stop?

Photo by Thanasis on Unsplash

Smoking is harmful to one’s health. It causes cancer and lung and heart disease. Most adult smokers continue smoking not because they really think it won’t harm them but because it’s very difficult to stop.

Tips for Stopping Smoking

Stopping isn’t easy. Many ex-smokers say it was the hardest thing they ever did. You know it’s worth the effort. And it’s easier if you think it through and make a good plan. There’s lots of help available. Before you quit, the US National Cancer Institute suggests you START with these five important steps:

If You Feel You Need Help

For more information and support to stop smoking, visit the Campus Health Centre.

What’s the Big Deal about Alcohol?

Of all the issues that can affect a student’s health and success in college, drinking causes more problems than anything else. When you drink too much, your judgment is impaired and you may behave in risky ways. Your health may be affected. Your studies likely are affected. Most college students report drinking at least some alcohol at some time, and even those who do not drink are often affected by others who do. College students experience injury and even death due to alcohol-related unintentional accidents; may be involved in alcohol-related physical assault, sexual assault or date rape, and may develop health issues including alcohol abuse and dependency problems. College students report academic consequences of their drinking, including missing class, falling behind, doing poorly on exams or papers, and receiving lower grades overall.

Photo by Thomas Picauly on Unsplash

So why is drinking so popular if it causes so many problems? You probably already know the answer to that: most college students say they have more fun when drinking. They’re not going to stop drinking just because someone lectures them about it.

Like everything else that affects your health and happiness, eating, exercise, use of other substances, drinking is a matter of personal choice. Like most decisions we all face, there are trade-offs. The most that anyone can reasonably ask of you is to be smart in your decisions. That means understanding the effects of alcohol and deciding to take control.

How Much Alcohol Is Too Much?

There’s no magic number for how many drinks a person can have and how often. If you’re of legal drinking age, you may not experience any problems if you have one or two drinks from time to time. Moderate drinking is not more than two drinks per day for men or one per day for women. More than that is heavy drinking.

Did you know that one night of heavy drinking can affect how well you think for two or three weeks afterward? This can really affect how well you perform as a student.

If You Feel You Need Help

Visit the campus Healht Centre or talk with your college counsellor. They understand how you feel and have a lot of experience with students feeling the same way. They can help.

Prescription and Illegal Drugs

People use drugs for the same reasons people use alcohol. They say they enjoy getting high. They may say a drug helps them relax or unwind, have fun, enjoy the company of others, or escape the pressures of being a student.

While alcohol is a legal drug for those above the drinking age, most other drugs, including the use of many prescription drugs not prescribed for the person taking them, are illegal. They usually involve more serious legal consequences if the user is caught. Some people may feel there’s safety in numbers: if a lot of people are using a drug, or drinking, then how can it be too bad? But other drugs carry the same risks as alcohol for health problems, a risk of death or injury, and a serious impact on your ability to do well as a student.

Good decisions also involve being honest with oneself. Why do I use (or am thinking about using) this drug? Am I trying to escape some aspect of my life (stress, a bad job, a boring class)? Could the effects of using this drug be worse than what I’m trying to escape?

If You Feel You Need Help

If you have questions or concerns related to drug use, your doctor or the campus Health Centre can help.

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/studyprocaff2/?p=95#h5p-19

Photo by freestocks.org on Unsplash

Sexuality is normal, natural human drive. As an adult, your sexuality is your own business. Like other dimensions of health, however, your sexual health depends on understanding many factors involving sexuality and your own values. Your choices and behavior may have consequences. Learning about sexuality and thinking through your values will help you make responsible decisions.

Sexual Values and Decisions

Image by jofreepik from Freepik

It’s often difficult to talk about sexuality and sex. Not only is it a very private matter for most people, but the words themselves are often used loosely, resulting in misunderstandings. Surveys have shown, for example, that about three-fourths of college students say they are “sexually active”—but survey questions rarely specify exactly what that phrase means. To some, sexual activity includes passionate kissing and fondling, while to others the phrase means sexual intercourse. Manual and oral sexual stimulation may or may not be included in an individual’s own definition of being sexually active.

We should therefore begin by defining these terms. First, sexuality is not the same as sex. Human sexuality is a general term for how people experience and express themselves as sexual beings. Since all people are sexual beings, everyone has a dimension of human sexuality regardless of their behavior. Someone who practices complete abstinence from sexual behavior still has the human dimension of sexuality.

Sexuality involves gender identity, or how we see ourselves in terms of maleness and femaleness, as prominently one or the other, or a combination of both or as neither, as well as sexual orientation, which refers to the gender qualities of those to whom we are attracted. The phrase sexual activity is usually used to refer to behaviors between two (or more) people involving the genitals—but the term may also refer to solo practices such as masturbation or to partner activities that are sexually stimulating but may not involve the genitals. For the purposes of this chapter, with its focus on personal health, the term sexual activity refers to any behavior that carries a risk of acquiring a sexually transmitted disease. This includes vaginal, oral, and anal intercourse. The term sexual intercourse will be used to refer to vaginal intercourse, which also carries the risk of unwanted pregnancy. We’ll avoid the most confusing term, sex, which in strict biological terms refers to reproduction but is used loosely to refer to many different behaviors.

There is a stereotype that sexual activity is very prominent among college students. One survey found that most college students think that other students have had an average of three sexual partners in the past year, yet 80 percent of those answering said that they themselves had zero or one sexual partner. In other words, college students as a whole are not engaging in sexual activity nearly as much as they think they are. Another study revealed that about 20 percent of eighteen- to twenty-four-year-old college students had never been sexually active and about half had not been during the preceding month. In sum, some college students are sexually active and some are not. Misperceptions of what others are doing may lead to unrealistic expectations or feelings. What’s important, however, is to be aware of your own values and to make responsible decisions that protect your sexual health.

Information and preparation are the focus of this section of the chapter. People who engage in sexual activity in the heat of the moment—often under the influence of alcohol—without having protection and information for making good decisions are at risk for disease, unwanted pregnancy, or abuse. Almost all college students know the importance of protection against sexually transmitted infections and unwanted pregnancy. So why then do these problems occur so often? Part of the answer is that we don’t always do the right thing even when we know it—especially in the heat of the moment, particularly when drinking or using drugs.

What’s “Safe Sex”?

Photo by Zackary Drucker as part of Broadly’s Gender Spectrum Collection.

It has been said that no sexual activity is safe because there is always some risk, even if very small, of protections failing. The phrase “safer sex” better describes actions one can take to reduce the risk of sexually transmitted infections and unwanted pregnancy.

Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs)

About two dozen different diseases can be transmitted through sexual activity. Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) range from infections that can be easily treated with medications to diseases that may have permanent health effects to HIV (human immunodeficiency virus), the cause of AIDS. Despite decades of public education campaigns and easy access to protection, STIs still affect many millions of people every year. Often a person feels no symptoms at first and does not realize he or she has the infection and thus passes it on unknowingly. Or a person may not use protection because of simple denial: “It can’t happen to me.” Although there are some differences, in most cases sexual transmission involves an exchange of body fluids between two people: semen, vaginal fluids, or blood (or other body fluids containing blood). Because of this similarity, the same precautions to prevent the transmission of HIV will prevent the transmission of other STIs as well.

Although many of these diseases may not cause dramatic symptoms, always see a health-care provider if you have the slightest suspicion of having acquired an STI. Not only should you receive treatment as soon as possible to prevent the risk of serious health problems, but you are also obligated to help not pass it on to others.

The following are guidelines to protect yourself against STIs if you are sexually active:

- Know that only abstinence is 100 percent safe. Protective devices can fail even when used correctly, although the risk is small. Understand the risks of not always using protection.

- Talk with your partner in advance about your sexual histories and health. Agree that regardless of how sure you both are about not having an STI, you will use protection because you cannot be certain even if you have no symptoms.

- Avoid sexual activity with casual acquaintances whose sexual history you do not know and with whom you have not talked about health issues. Sexual activity is safest with a single partner in a long-term relationship.

- Use a latex condom for all sexual activity. A male condom is about 98 percent effective when used correctly, and a female condom about 95 percent effective when used correctly. With both, incorrect use increases the risk. If you are unsure how to use a condom correctly and safely, do some private online reading.

- If you are sexually active with multiple partners, see your health-care provider twice a year for an STI screening even if you are not experiencing symptoms.

Preventing Unwanted Pregnancy

Photo by Crew on Unsplash

Heterosexual couples who engage in vaginal intercourse are also at risk for an unwanted pregnancy. There are lots of myths about how a woman can’t get pregnant at a certain time in her menstrual cycle or under other conditions, but in fact, there’s a risk of pregnancy after vaginal intercourse at any time. All couples should talk about protection before reaching the stage of having intercourse and take appropriate steps. While a male condom is about 98 percent effective, that 2 percent failure rate could lead to tens of thousands of unintended pregnancies among college students. When not used correctly, condoms are only 85 percent effective.

In addition, a couple that has been healthy and monogamous in their relationship for a long time may be less faithful in their use of condoms if the threat of STIs seems diminished. Other methods of birth control should also therefore be considered. With the exception of the male vasectomy, at present most other methods are used by the woman. They include intrauterine devices (IUDs), implants, injected or oral contraceptives (the “pill”), hormone patches, vaginal rings, diaphragms, cervical caps, and sponges. Each has certain advantages and disadvantages.

Birth control methods vary widely in effectiveness as well as potential side effects. This is therefore a very personal decision. In addition, two methods can be used together, such as a condom along with a diaphragm or spermicide, which increases the effectiveness. (Note that a male and female condom should not be used together, however, because of the risk of either or both tearing because of friction between them.) Because this is such an important issue, you should talk it over with your health-care provider, or a professional at your student health center.

In cases of unprotected vaginal intercourse, or if a condom tears, emergency contraception is an option for up to five days after intercourse. Sometimes called the “morning after pill” or “plan B,” emergency contraception is an oral hormone that prevents pregnancy from occurring. It is not an “abortion pill.”

Sexual Assault and Date Rape

Sexual assault is a serious problem in Canada generally and among college students in particular. In Canada, one-in-five women will be sexually assaulted.

Sexual assault is any form of sexual contact without voluntary consent. Although rape has no specific provision in Canada’s Criminal Code [5], rape is usually more narrowly defined as “unlawful sexual intercourse or any other sexual penetration of the vagina, anus, or mouth of another person, with or without force, by a sex organ, other body part, or foreign object, without the consent of the victim. Both are significant problems among college students.

Photo by Mihai Surdu on Unsplash

Although men can also be victims of sexual assault and rape, the problem usually involves women. Men must also understand what is involved in sexual assault and help build greater awareness of the problem and how to prevent it.

Sexual assault is so common in our society in part because many people believe in myths about certain kinds of male-female interaction. Common myths include “It’s not really rape if the woman was flirting first” and “It’s not rape unless the woman is seriously injured.” Both statements are not legally correct. Another myth or source of confusion is the idea that “Saying no is just playing hard to get, not really no.” Men who really believe these myths may not think that they are committing assault, especially if their judgment is impaired by alcohol. Other perpetrators of sexual assault and rape, however, know exactly what they’re doing and in fact may plan to overcome their victim by using alcohol or a date rape drug.

Many college administrators and educators have worked very hard to promote better awareness of sexual assault and to help students learn how to protect themselves. Yet colleges cannot prevent things that happen at parties and behind closed doors. Students must understand how to protect themselves.

Perpetrators of sexual assault fall into three categories:

- Strangers

- Acquaintances

- Dating partners

Among college students, assault by a stranger is the least common because campus security departments take many measures to help keep students safe on campus.

Nonetheless, use common sense to avoid situations where you might be alone in a vulnerable place: Walk with a friend if you must pass through a quiet place after dark. Don’t open your door to a stranger. Don’t take chances.

Most sexual assaults are perpetrated by acquaintances or date partners. Typically, an acquaintance assault begins at a party. Typically, both the man and the woman are drinking—although assault can happen to sober victims as well. The interaction may begin innocently, perhaps with dancing or flirting. The perpetrator may misinterpret the victim’s behavior as a willingness to share sexual activity, or a perpetrator intent on sexual activity may simply pick out a likely target. Either way, the situation may gradually or suddenly change and lead to sexual assault.

Prevention of acquaintance rape begins with the awareness of its likelihood and then taking deliberate steps to ensure you stay safe at and after the party:

- Go with a friend and don’t let someone separate you from your friend.

- Agree to stick together and help each other if it looks like things are getting out of hand. If your friend has too much to drink, don’t leave her or him alone.

- Plan to leave together and stick to the plan. Be especially alert if you become separated from your friend, even if you are only going off alone to look for the bathroom. You may be followed.

- Be cautious if someone is pressuring you to drink heavily.

- Trust your instincts if someone seems to be coming on too aggressively.

- Get back to your friends. Know where you are and have a plan to get home if you have to leave abruptly.

These preventions can work well at a party or in other social situations, but they don’t apply to most dating situations when you are alone with another person. About half of sexual assaults on college students are date rape. An assault may occur after the first date, when you feel you know the person better and perhaps are not concerned about the risk. This may actually make you more vulnerable, however.

Until you really get to know the person well and have a trusting relationship, follow these guidelines to lower the risk of sexual assault:

- Make it clear that you have limits on sexual activity. If there is any question that your date may not understand your limits, talk about your values and limits.

- If your date initiates unwanted sexual activity of any sort, do not resist passively. The other may misinterpret passive behavior as consent.

- Be careful if your date is drinking heavily or using drugs. Avoid drinking yourself, or drink very moderately.

- Stay in public places where there are other people. Do not invite your date to your home before your relationship is well established.

- Trust your instincts if your date seems to be coming on too strong. End the date if necessary.

If you are sexually assaulted, always talk to someone. Contact your college counselling department for support services and other resources or contact Student Health Services. Even if you do not report the assault to law enforcement, it’s important to talk through your feelings and seek help if needed to prevent an emotional crisis.

Date Rape Drugs

In addition to alcohol, sexual predators use certain commonly available drugs to sedate women for sexual assault. They are odorless and tasteless and may be added to a punch bowl or slipped into your drink when you’re not looking. These drugs include the sedatives GHB, sometimes called “liquid ecstasy,” and Rohypnol, also called “roofies.” Both cause sedation in small doses but can have serious medical effects in larger doses. Date rape drugs are typically used at parties.

Use the following tips to protect yourself against date rape drugs:

- Don’t put your drink down where someone else may get to it. If your drink is out of your sight for even a moment, don’t finish it.

- Never accept an open drink. Don’t accept a mixed drink that you did not see mixed from pure ingredients.

- Never drink anything from a punch bowl, even if it’s nonalcoholic. You can’t know what may have been added into the punch.

- If you experience unexpected physical symptoms that may be the result of something you drank or ate, get to an emergency room and ask to be tested.

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/studyprocaff2/?p=95#h5p-20

As college is often students’ first time away from home, Sexual Assault and Sexual Violence prevention is a high priority on college campuses. It is important for you to understand and gain consent from your partner before engaging in any sexual contact.

What is Consent?

Consent is defined as the voluntary agreement to engage in sexual activity. In other words, you must actively and willingly give consent to sexual activity. Any type of sexual activity without consent is sexual assault.

Consent:

- should never be assumed or implied

- is not silence or the absence of “no”

- can be withdrawn at any time

- cannot be given if you are impaired by alcohol or drugs, or unconscious

- can never be obtained through threats or coercion

- cannot be given if the perpetrator abuses a position of trust, power or authority

- cannot be given by anyone other than the person participating in the sexual activity

The best way to ensure both parties are comfortable with any sexual activity is to talk about it. Ask questions to make sure your partner is comfortable.

Stop when you are asked or told to stop and respect the answer right away. Verbally saying “no” is not the only way for someone to tell you to stop. Look for gestures and body language that indicate someone is not willing to participate.

Consent to one activity, one time, does not mean consent to another or to a set of actions, respect someone’s boundaries if they don’t want to participate.

This short video was developed by Blue Seat Studios and explains consent by connecting sexual consent to offering your partner a cup of tea. It is a lighthearted but effective way to think about consent.

- Maintaining a health lifestyle that includes eating well, exercise, and proper sleep. A healthy lifestyle reduces stress, improves mood, and increases your capacity to learn.

- Be aware of the effects substances have on your health and student life. Substance use is a personal choice and like most choices, there are trade-offs. These trade-offs can unintentionally affect you and others.

- Every college has policies on Respect and Sexual Assault and provides sexual health resources and services. All students must understand how to protect their sexual health. Thinking about choices, behavior and values helps with responsible decision making.

The Learning Portal provides information and advice on improving your Physical Health.