Outdoor Learning in Canada Copyright © 2024 by Simon Priest; Stephen D. Ritchie; and Daniel B. Scott is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Outdoor Learning in Canada Copyright © 2024 by Simon Priest; Stephen D. Ritchie; and Daniel B. Scott is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

1

This resource funded by the Government of Ontario. The views expressed in this publication are the views of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the Government of Ontario.

2

We would like to acknowledge that the land which we reintroduce as Canada is the traditional territory of many diverse Indigenous peoples, communities, and nations across the vast country. We recognize and deeply appreciate their historic connection to regional territories and their ongoing contributions to the society and culture of Canada. We also acknowledge the impact of colonization and ongoing systemic oppression and commit to working towards reconciliation and decolonization through the diverse research and practices related to outdoor learning in Canada.

I

1

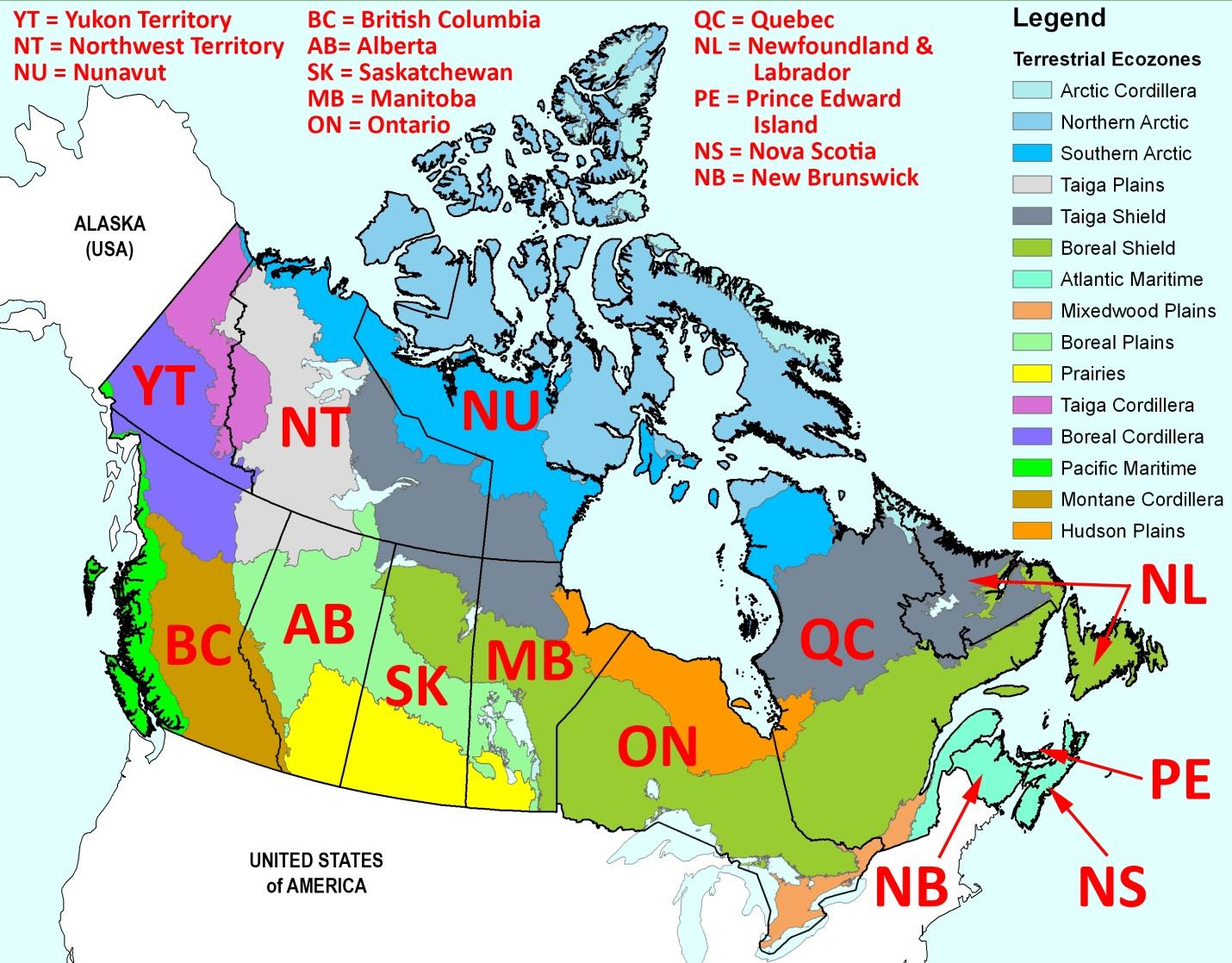

Canada is a vast country in North America and indeed the world. However, relevant to outdoor learning in Canada (OLiC), it is important to reintroduce several other distinct socio-political characteristics. Despite the vast geography, the population of 39 million (Statistics Canada, 2022a) is relatively low compared to many other nations around the world, and the vast majority of this population lives in close proximity to the southern border with our influential neighbour, the United States (aka America). As a progressive social democracy, Canada has a distributed power and governance structure with the 10 provinces and three territories responsible for education, health, social services, and resource management. For example, see the differences across education at https://www.cmec.ca/299/Education_in_Canada__An_Overview.html.

French and English are the official languages and cultures in Canada, although there are also seven million (18%) other immigrant people, who speak other languages and have distinct cultural practices (EduCanada, 2022). The 1.8 million (5%) Indigenous people in Canada include First Nations, Inuit, and Métis people (Statistics Canada, 2022b), and these populations represent hundreds of communities, dozens of distinct languages, and unique histories. These people live in geographically dispersed land territories from coast to coast, including in the far north (Government of Canada, 2022a). Thus, OLiC is as diverse as the socio-political characteristics across the nation.

However, despite being overshadowed and strongly influenced by our nearest neighbour, America, Canada does have its own unique culture and zeitgeist (Government of Canada, 2021). Canadians are heavily pressured by British, French, and American interests as indicated by our mixed spelling (colour/color, theatre/theater, or grey/gray) and mixed measurements (outside temperatures in Celsius/cooking temperatures in Fahrenheit, food weights in kilograms/body weights in pounds, and lengths in metres/heights in feet). To begin, we would like to reintroduce (or remind you of) some additional proud Canadian facts, current at the time of publication: 2023. Perhaps you already knew…

With the size of the country, its long coastline, bountiful freshwater lakes, sparse population, and rich wilderness, one can easily see how Indigenous Peoples developed unique modes of travel including the canoe, the kayak, and the snowshoe. These uniquely Canadian methods of travel have figured prominently in the evolution of Canadian outdoor learning and have been adopted by several nations, where the word “Canadian” often precedes canoe, kayak, or snowshoe to distinguish it from local variations. This Indigenous contribution to Canadiana is well documented (Newhouse et al., 2005).

This final fact makes Canada’s treatment of Indigenous people that much more shameful, especially with regard to their health and colonization history (McCallum, 2017). Like many nations, Canada apologized for lasting imperial oppression and struck a Truth and Reconciliation Commission to address the past, but failed to account for previous wrongs by not openly allowing Indigenous self-determination and not returning access to their lands (Corntassel & Holder, 2008).

From an Indigenous perspective, outdoor learning is often referred to as land-based learning, or simply connecting with the land. Indigenous people in Canada are known for their deep understanding and connection to the land, their passionate stewardship of natural resources, and their leadership in conservation and environmental activism. Thus, the Indigenous knowledges and teachings related to the land and all of creation are an incredibly rich resource for outdoor learning practitioners across Canada.

Native Land Digital was created by Canadians in 2018 to provide an online centralized resource (https://native-land.ca/) for identifying international Indigenous territories. Thus, this resource can be used by outdoor learning practitioners to identify the traditional territories, languages, and treaties associated with the region they are practicing outdoor learning anywhere across the country and around the world.

Outdoor learning has a unique opportunity to heal intergenerational trauma and contribute to further reconciliation through its inherent process of democratizing social injustice, challenging systems of privilege, and growing citizens who will solve the world’s future big problems (Priest & Asfeldt, 2022; Priest & Henderson, 2021).

Agriculture and Agri-food Canada. (2011). Canadian Maple Syrup. http://www5.agr.gc.ca/resources/prod/Internet-Internet/MISB-DGSIM/CB-MC/PDF/4689-eng.pdf

Barh, S. (2020, September 20). ‘Schitt’s Creek’ sets an Emmy record. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/20/arts/television/emmys-schitts-creek.html

BC Ombudsperson. (2006). Quick tips of apologies. https://bcombudsperson.ca/assets/media/Quick-Tips-Apology.pdf

Canadian Encyclopedia. (2023). Métis (Plain Summary). https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/metis-plain-language-summary

Canadian Geographic. (2019). Animal facts: Beaver. https://canadiangeographic.ca/articles/animal-facts-beaver/

CBC Sports. (2017, June 15). How Canada invented “American” football, baseball, basketball and hockey. https://www.cbc.ca/sportslongform/entry/how-canada-invented-american-football-baseball-basketball-and-hockey

Corntassel, J. & Holder, C. (2008). Who’s sorry now? Government apologies, Truth commissions, and Indigenous self-determination in Australia, Canada, Guatemala, and Peru. Human Rights Review, 9, 465–489.

Desai, N. (2016, February 26). Opinion: Myth of Canadian complacency has permeated our highest echelons. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/report-on-business/rob-commentary/myth-of-canadian-complacency-has-permeated-our-highest-echelons/article28915265/

Ecological land classification. (2017). https://www.statcan.gc.ca/eng/subjects/standard/environment/elc/elc2017

EduCanada. (2022). Canada’s languages. https://www.educanada.ca/study-plan-etudes/during-pendant/languages-langues.aspx?lang=eng

Global Entrepreneurship Monitor. (2021). 2020/2021 global report. https://www.gemconsortium.org/report

Government of Canada. (2021). Canada-United States relations. https://www.international.gc.ca/country-pays/us-eu/relations.aspx

Government of Canada. (2022a). Indigenous peoples and communities. https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1100100013785/1529102490303

Government of Canada. (2022b). What you need to know about cannabis. https://www.canada.ca/en/services/health/campaigns/cannabis/canadians.html

Government of Canada. (n.d.). The history of the national flag of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/canadian-heritage/services/flag-canada-history.html

Guinness World Records. (2019). https://www.guinnessworldrecords.com/

History 101. (2022, May 11). The great Canadian maple syrup heist. https://www.history101.com/the-great-canadian-maple-syrup-heist/

la Banquise. (n.d.). History of Poutine. https://labanquise.com/en/poutine-history.php

Lacrosse Canada. (1995). History of lacrosse. https://www.lacrosse.ca/content/History-of-Lacrosse

McCallum, M.J.L. (2017). Starvation, experimentation, segregation, and trauma: Words for reading Indigenous health history. The Canadian Historical Review, 98(1), 96-113.

Messager, M., Lehner, B., Grill, G., Nevada, I. & Schmitt, O. (2016). Estimating the volume and age of water stored in global lakes using a geo-statistical approach. Nature Communications, 7, 13603.

Newhouse, D.R., Voyageur, C.J., & Beavon, D. (2005). Hidden in plain sight: Contributions of Aboriginal peoples to Canadian identity and culture. University of Toronto Press.

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2021). https://data.oecd.org/canada.htm

Priest, S., & Asfeldt, M. (2022). The history of outdoor learning in Canada. The International Journal of the History of Sport, 39(5), 489-509.

Priest, S., & Henderson, B. (2021). Why is outdoor learning not a bigger part of Canadian education? Pathways: The Ontario Journal of Outdoor Education, 34(1), 4–18.

Rideau Hall Foundation. (2019). Canada’s culture of innovation index. https://rhf-frh.ca/innovation-index/

Statistics Canada. (2022a). Canada’s population estimates, third quarter 2022. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/221221/dq221221f-eng.htm

Statistics Canada. (2022b). Indigenous population continues to grow and is much younger than the non-Indigenous population, although the pace of growth has slowed. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/220921/dq220921a-eng.htm

Statistics Canada. (n.d.). Canada yearbooks (Archived). https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/11-402-x/2012000/chap/geo/geo-eng.htm

Trans Canada Trail. (n.d.). Welcome to the Trans Canada Trail. https://tctrail.ca/

US News & World Report. (2021). https://www.usnews.com/news/best-countries/rankings-index

World Atlas. (2021, February 25). https://www.worldatlas.com/maps/canada

World Atlas. (n.d.). https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/which-country-is-known-as-the-great-white-north.html

World Factbook. (2021). https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/field/coastline/

Simon Priest

Simon Priest was a university professor of adventurous and environmental outdoor learning in Ontario. Internationally, he has been a Dean, Provost, Vice-Chancellor, Senior Vice President, President, Commissioner, and Advisor to a Minister of Education. He has received numerous awards and accepted over 30 visiting scholar positions around the world in outdoor learning. Now early retired in British Columbia, he spends his time hiking, gardening, researching, teaching, and writing.

Stephen D. Ritchie

Laurentian University

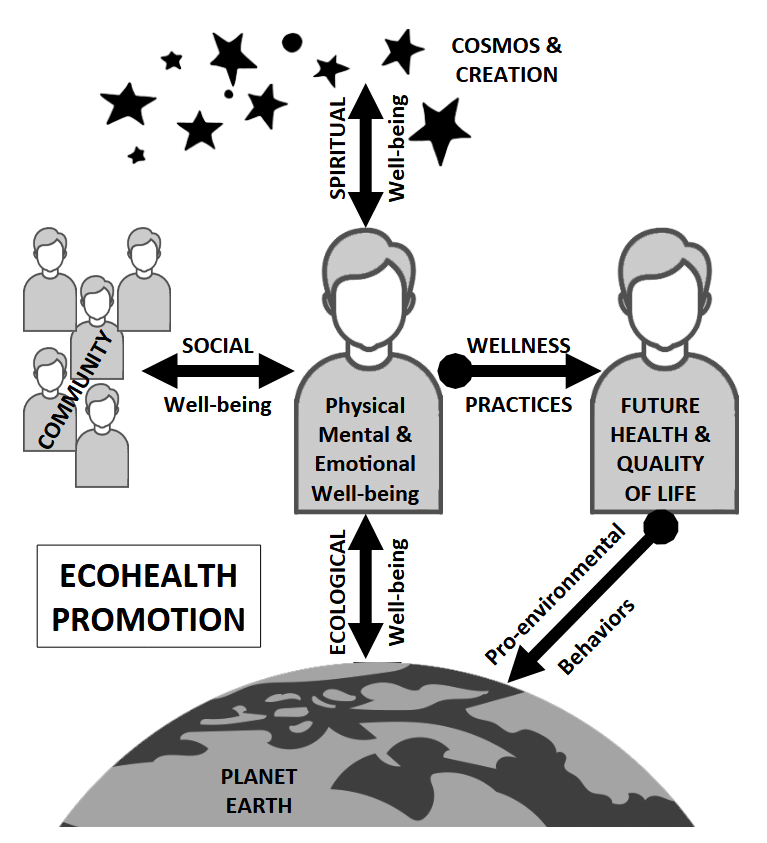

Stephen D. Ritchie is an Associate Professor in the School of Kinesiology and Health Sciences in Sudbury, Ontario, Canada. His current research and teaching interests are focused on: (1) understanding ecohealth promotion in the context of achieving personal growth and holistic health outcomes through outdoor learning, adventure, and contact with nature, and (2) applying diverse program evaluation approaches in outdoor learning, Indigenous health, and other contexts.

Reintroducing Canada! Copyright © 2024 by Simon Priest and Stephen D. Ritchie is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

2

Authors’ note: Spirituality in this chapter refers to comprehending our place in the world–our search for satisfaction or serenity, why we were put here, and what role we were meant to play with others and nature–during our brief time on the planet, with or without religion or transcendence.

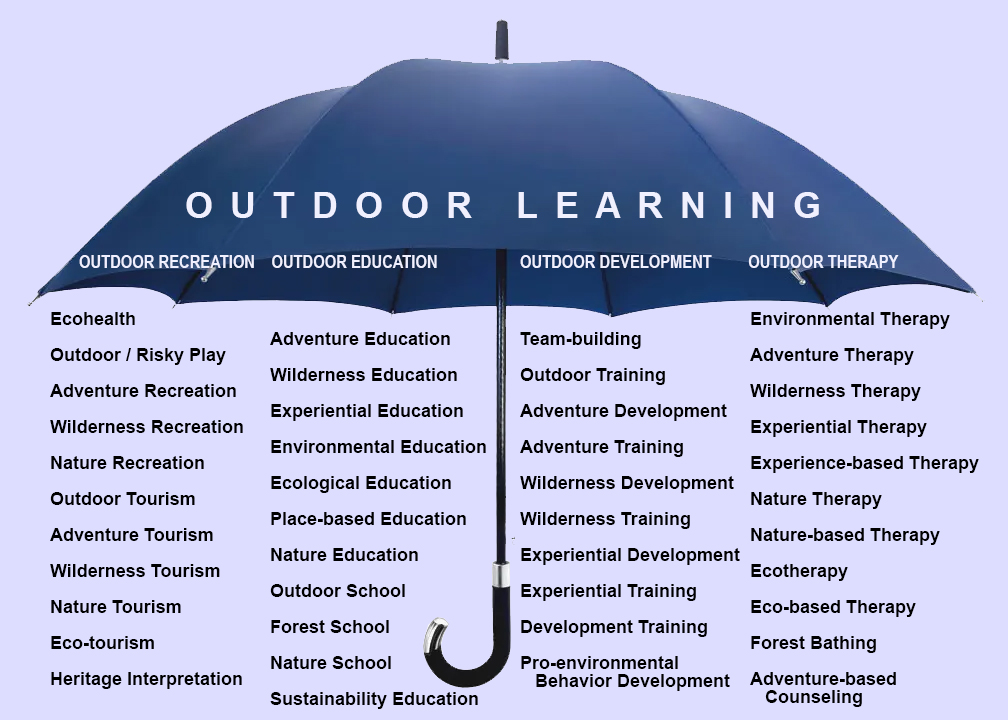

The umbrella term of outdoor learning has been difficult to define due to the wide variety of programs that exist, thrive, and survive under its cover. Figure 1 lists just a few of its synonymous labels. One of the earliest recent definitions came from England: “Outdoor Learning is a broad term that includes: outdoor play in the early years, school grounds projects, environmental education, recreational and adventure activities, personal and social development programmes, expeditions, team building, leadership training, management development, education for sustainability, adventure therapy … and more” (English Outdoor Council, 2018; Greenaway, 2005).

Another British organization, unfortunately, used the words “learning” and “outdoors” to define outdoor learning as “actively inclusive facilitated approaches that predominately use activities and experiences in the outdoors which lead to learning, increased health and wellbeing, and environmental awareness” (Institute for Outdoor Learning, 2021). They later substituted “nature” for “the outdoors” and “change” for “learning.” However, the learning leads to more than just wellness and environmental outcomes.

The National Curriculum of Australia (2020) states that “the development of positive relationships with others and with the environment through interaction with the natural world … are essential for the wellbeing and sustainability of individuals, society and our environment. Outdoor learning engages students in practical and active learning experiences in natural environments and settings, and this typically takes place beyond the school classroom. In these environments, students develop the skills and understandings to move safely and competently while valuing a positive relationship with natural environments and promoting the sustainable use of these environments.”

In the United States, Americans use the term “experiential education” to emphasize the learning methods and innovative teaching/facilitating used extensively with participants in the outdoors. “Experiential education is a teaching philosophy that informs many methodologies in which educators purposefully engage with learners in direct experience and focused reflection in order to increase knowledge, develop skills, clarify values, and develop people’s capacity to contribute to their communities” (Association for Experiential Education, n.d.).

Definitions from the nations above share some common content: experiential, relationships, and nature or natural environments. In this book, the umbrella term of Canadian outdoor learning is defined using these commonalities as “an experiential process … which takes place primarily through exposure to the out-of-doors [where] the emphasis for the subject of learning is placed on … [five] relationships concerning people and natural resources” (Priest, 1986, p. 13). Those five relationships include:

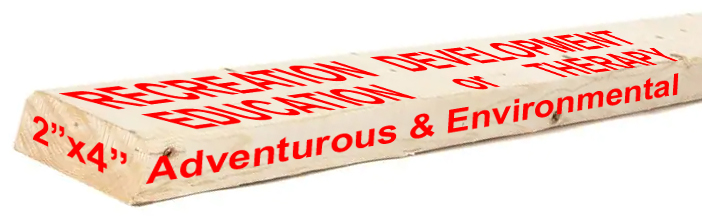

Outdoor learning involves teaching with a two-by-four: two branches of activities and four types of programs. Truly effective outdoor learning utilizes both branches of activities within each of the four program types to teach about and bring about much-needed change associated with all five relationships. In fact, practitioners may have great difficulty having an impact on spiritual relationships without first successfully addressing the other four. Participants who know themselves and how to work with others and who know an ecosystem and how they affect it and how it affects them can decide how they best fit in.

Outdoor learning has two activity sides: adventurous and environmental. Adventurous activities range from games and group problem-solving initiatives, to low and high ropes/challenge courses, to one-day excursions or multi-day expeditions (snowshoeing, skiing, bicycling, hiking, climbing, caving, canoeing, kayaking, sailing, and more). Environmental activities range from sensory immersion in nature, to mindful meditation or contemplation, to scientific or artistic ecological exercises conducted outdoors in natural surroundings (Canadian Outdoor Therapy and Healthcare, n.d.).

Outdoor learning comes in four program types depending on what the lesson is meant to change: feeling, thinking, behaving, or resisting efforts to create positive change as shown in Table 1 below. Outdoor recreation (including tourism) changes the way participants feel through fun, play, enjoyment, and the learning of new activity skills. Outdoor education changes the way participants think by gaining new concepts, reinforcing old ones, and creating an awareness of the need to change behaviours. Outdoor development changes the way participants behave by enhancing positive actions and increasing their functioning. Outdoor therapy changes the way participants resist efforts to transform them positively by reducing negative or maladaptive behaviours in order to ease their dysfunction (Priest, 2021).

OUTDOOR… | RECREATION | EDUCATION | DEVELOPMENT | THERAPY |

Intends to change | Feeling | Thinking | Behaving | Resisting Change |

Subject matter or learning focused on | Having fun, playing, enjoying, learning new activity skills | Gaining new and old concepts or awareness of need to make changes | Enhancing positive conduct or actions (grow functioning) | Reducing negative conduct or actions (ease dysfunction) |

For example, adventurous activities range from guided mountain climbing or sailing with tourists, to schoolyard socialization games and corporate team-building events, to a wilderness expedition for youth with substance abuse or criminal histories. Similarly, the use of environmental activities can progress from ecological interpretation or wildlife identification with a naturalist, through high school sustainability awareness exercises and pro-environmental action inculcated by teachers, to treating stress, anxiety or depression in adults via immersion into natural greenspace with a therapist.

This chapter has provided a very brief introduction to outdoor learning. The following chapters present an overview of outdoor learning in Canada. Subsequent chapters will address various topics that practitioners may find helpful in their outdoor learning work with Canadian participants. Each chapter will define terms as these arise, but in this chapter Canadian outdoor learning is an experiential process that takes place primarily through exposure to nature and the outdoors, where the emphasis is on one or more relationships concerning people and nature.

Adventurous learning develops intrapersonal and interpersonal relationships, while environmental learning develops ecosystems and ekistic relationships. Employed together, these two outdoor learning approaches can develop spiritual relationships. Improving these five relationships can help participants change the way they feel, think, behave, and/or resist positive efforts to change (Priest & Gass, 2018).

This historic definition puts outdoor learning in a nice box that satisfies the policy and procedure makers of our society. However, in the future, we must think outside that box. In many ways Canada is behind other developed nations when examining state-of-the-art practices for outdoor learning, but we do have an advantage in our efforts toward truth and reconciliation with Indigenous Canadians and toward partnerships with nature for change. In a solution-focused manner, we must do more of what is starting to work for us.

While honouring our past work, outdoor learning in Canada is ready for a revolution of new ideas. The ignition for some of those new ideas can be found herein with chapters on indigeneity, decolonization, ecohealth, climate collapse, nature reciprocity, trauma-informed care, racial imbalances, temporary able-bodiedness, and different ways of thinking and acting.

With the plethora of problems related to the Earth’s systems as the result of previous ways of thinking and acting, what we must also begin to “do more of” is include expert voices from all genders, ethnicities, indigeneities, and orientations. Canada is a diverse pluralistic society and outdoor learning must include all of those elements. To this end, we invite and welcome additional contributions to this living textbook and especially gifts from authors who are not simply defined by an older white cis-male identity.

Association for Experiential Education. (2024). What is experiential education. https://www.aee.org/what-is-experiential-education

Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority. (2020). Outdoor learning. Australian Curriculum. https://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/resources/curriculum-connections/portfolios/outdoor-learning/

Canadian Outdoor Therapy & Healthcare. (n.d.). Best practices: Activities. Canadian Outdoor Therapy & Healthcare. Retrieved February 11, 2024, from http://coth.ca/prac.html#ACT

English Outdoor Council. (2018). What is outdoor learning? https://www.englishoutdoorcouncil.org/outdoor-learning/what-is-outdoor-learning

Greenaway, R. (2005). What is outdoor learning. https://web.archive.org/web/20231003040318/https://www.outdoor-learning-research.org/Research/What-is-Outdoor-Learning

Institute for Outdoor Learning. (2021). Outdoor learning. https://www.outdoor-learning.org/Portals/0/IOL%20Documents/About%20Outdoor%20Learning/RR1%20-%20Describing%20Outdoor%20Learning%202-8-21.pdf?ver=2021-08-10-133755-690

Priest, S. (1986). Redefining outdoor education: A matter of many relationships. The Journal of Environmental Education, 17(3), 13–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958964.1986.9941413

Priest, S. (2021). Adventure therapy in Canada. Academia Letters. https://doi.org/10.20935/AL3831

Priest, S., & Gass, M. A. (2018). Effective leadership in adventure programming (Third Edition). Human Kinetics.

Simon Priest

Simon Priest was a university professor of adventurous and environmental outdoor learning in Ontario. Internationally, he has been a Dean, Provost, Vice-Chancellor, Senior Vice President, President, Commissioner, and Advisor to a Minister of Education. He has received numerous awards and accepted over 30 visiting scholar positions around the world in outdoor learning. Now early retired in British Columbia, he spends his time hiking, gardening, researching, teaching, and writing.

Introduction: What Is Outdoor Learning? Copyright © 2024 by Simon Priest is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

II

3

Authors’ note: We wish to thank John Shultis and Jim Butler for thoughtful contributions to this chapter.

One of the founders of interpretation, Freeman Tilden (1977, p. 8), defined interpretation as “an educational activity which aims to reveal meanings and relationships through the use of original objects by firsthand experience and by illustrative media rather than simply to communicate factual information.” Interpretation Canada suggests that, in fact, no single definition can capture the vibrancy of the field, but each effort provides a place in which to begin understanding. They put forth that “interpretation is any communication process designed to reveal meanings and relationships of cultural and natural heritage to the public, through first-hand involvement with an object, artifact, landscape or site” (Interpretation Canada, 1976). Based on these definitions, interpretation is different from other methods of communicating information in that it reveals meanings about that information and that interpretation seeks to provoke (Tilden, 1977) and inspire visitors (Gilson, 2020). The purpose of this chapter is to describe the characteristics of interpretation (compared to education), its history in Canada, and research on the positive impacts and effective strategies of interpretation.

Interpretation occurs in many ways and in various locales (e.g. zoos, museums, parks and protected areas, outdoor recreation landscapes, ecotourism settings), but has two basic categories. First, personal interpretation consists of direct contact between the interpreter and the visitor. Here are several instances.

Second, non-personal interpretation connects visitors through the use of inanimate interpretive media. Here are some examples.

Effective interpretation typically embraces the following attributes (adapted from Hvenegaard and Shultis, 2016):

Nature interpretation regularly occurs in zoos, parks and protected areas, museums, and other outdoor recreation contexts. At the same time, much nature interpretation also occurs within the context of ecotourism, a form of tourism (e.g., birding, whale watching, nature photography, and botanical study) in which visitors engage in nature-based activities that have a significant educational component and promote a conservation ethic (Weaver, 2002). In contrast, environmental education programs offered by nature-related agencies typically target K-12 children to fulfil part of their school curriculum). Overall, interpretation provides important benefits to participants through learning and enjoyment but also to the natural environment, conservation agencies, parks and protected areas, wildlife, and society in general through enlightened attitudes, changed behaviours, and connections to place.

In Canada, nature interpretation began with various park, outdoor recreation, and municipal agencies. James Harkin (1957, p. 15), Canada’s first Commissioner of National Parks, while reflecting back on a long career in public service, argued that Canada needs “an informed public opinion which will voice an indignant protest against any vulgarization of the beauty of our National Parks.” Nature interpretation in the national parks began in 1887, two years after what would become Banff National Park was established, when a guide led interpretive walks in the lower Hot Springs cave. The first park interpretive museum was established at Banff in 1895, and interpretive tours began in the Nakimu Caves in Glacier National Park, British Columbia in 1905. The national parks hired seasonal interpreters in 1929 and permanent interpreters in 1931. In the 1940s, Hubert Green lobbied the federal government for dedicated funding for environmental education in Banff and, over the course of the next 20 years, was able to build support, funding, and policy to hire the first permanent naturalist in 1964 (Federation of Alberta Naturalists, 2005).

Outside of the national parks, interpretive programs in Ontario’s provincial parks began in 1954; Alan Helmsley was hired in 1955, almost 10 years after his first summer as a seasonal naturalist in Algonquin Provincial Park. Under Helmsley’s supervision, the Ontario interpretive program grew to be internationally recognized and a leader across Canadian parks, expanding from two to eleven parks and seeing participation rise four-fold from 1956 to 1964 (Killian, 1993). Other provinces and territories soon followed, with Alberta Provincial parks hiring their first park naturalist in 1968 to establish an interpretive centre in Cypress Hills Provincial Park (Alberta Parks, 2018) and continuing to expand over the past 50 years to now serve more than 450,000 participants annually (Alberta Parks, 2016).

Outside of national and provincial parks, the first Canadian Wildlife Service interpretation centre opened in 1965 at Wye Marsh, near Midland, Ontario. Interpretation Canada, the nationwide organization that promotes networking, professionalism, and hiring, was established in 1977. Many municipalities across the country now have nature interpretation centres and interpretive programs.

Interpretation in Canada has often changed in response to coordinated planning efforts, policy shifts, the hiring and training of interpreters, visitor demands, and new technologies. These changes suggest four phases (Hvenegaard and Shultis, 2016). Phase 1 concentrated on familiarising visitors with the most unique and majestic features of an area (e.g., hot springs and waterfalls) and providing explanations. As public awareness of the environment increased in the early 1960s, Phase 2 focussed on the broader landscape, the many interrelationships in ecosystems, and management issues (e.g. crowding and environmental impacts of recreation). In the early 1970s, Phase 3 saw interpretation begin to address broader ecological mindfulness among visitors by focussing more on regional ecosystems. Finally, in the 2000s and beyond, Phase 4 saw interpretive agencies move off-site to engage with people who have not visited parks and nature sites (e.g., young people, new Canadians, ethnic minorities, and urban residents), often employing rapidly improving technology such as virtual reality depictions of remote and difficult to access conservation areas and social media messaging to reach younger generations who are digital natives. While interpretation has changed over the decades, elements of stewardship and broader systems level approaches have continued throughout the phases.

As humans increasingly degrade the natural environment, the need grows to effectively communicate stewardship principles and environmental ethics. While environmental education serves a similar purpose, interpretation is unique in its provocation approach and focus on free choice learning and people in leisure settings. As a result, there are many reasons for providing nature interpretation.

First, interpretation has the ability to instil passion in participants, influence values, attitudes, and behaviours towards sustainability and stewardship, and create awareness of relevant environmental and cultural issues (Stern & Powell, 2020). Research shows that interpretation generates significant improvements in the knowledge and awareness of environmental issues. For example, visitor knowledge increased from 37% correct before a white-water rafting trip in Grand Canyon National Park to 60% correct after the trip (Powell et al., 2009). Similarly, more than three quarters of participants in an “animal talk” at the Wellington Zoo (New Zealand) increased their knowledge and were able to recall the conservation message (MacDonald et al., 2016).

Second, many visitors want interpretation because it adds value to their experiences. In general, people visiting parks expect and value contact with interpretive staff. Moreover, attending interpretive programs increases satisfaction of visitors (in parks and in almost all settings) when compared to those who do not attend personal interpretative program (Ham & Weiler, 2007; Stern et al., 2011). More than 80% of visitors to the Panama Canal Watershed area reported being highly satisfied with their overall experience and were particularly satisfied with the personal interpretation presentations and exhibits (compared to other services or non-personal interpretation). Furthermore, satisfaction (as a result of interpretive programs) increased both pro-environmental behavioural intentions and conservation attitudes of ecotourism resort visitors (Lee & Moscardo, 2005).

Finally, depending on the setting, interpretation is provided under the jurisdiction of the federal, provincial, and territorial governments or municipalities. Thus, interpretive goals and approaches are shaped by relevant legislation and policies. For example, national parks are created for the “benefit, education, and enjoyment” of the people of Canada (Government of Canada, 1990: 3). Similarly, the vision for provincial parks in Alberta is to “inspire people to discover, value, protect, and enjoy the natural world (Government of Alberta, 2009). Interpretation supports park agency goals through enhanced visitor experiences, increased stewardship behaviours, and improved awareness and education. These results allow policy and management decisions to be actioned in tangible ways (Hvenegaard et al., 2023).

Despite the many reasons for providing nature interpretation opportunities, there are also barriers for many potential participants. Participation in personal interpretive activities can be low, ranging from 10-25% of visitors (Stern et al., 2011; Hvenegaard, 2011). Constraints include the amount of time, awareness of programs, information availability, life stages of the potential participant, perceptions about programming choices, competing activities, cost, and timing (Hvenegaard, 2017).

There are a few Canadian studies on the effectiveness of nature interpretation that illustrate uniquely Canadian approaches. In Pacific Rim National Park Reserve, BC, Randall and Rollins (2006) examined the role of kayak tour guides in educating visitors and influencing attitudes. About 82% of guided visitors were less-experienced kayakers, whereas 71% of non-guided visitors were more-experienced kayakers. For visitors on non-guided trips, pre-trip knowledge scores (based on ten true/false questions) did not differ from post-trip scores; however, for visitors on guided trips, scores rose from 5.3 before the trip to 6.5 after the trip. For attitudes, researchers asked only guided visitors whether they supported, opposed, or were indifferent to a policy promoting visitors to voluntarily give up fishing on their trips because of potential impacts on the threatened rockfish population. When guides commented on the ‘no fish policy,’ visitors were more likely to support the policy than when guides did not comment on the policy. Overall, tour guides were influential in developing knowledge and shaping attitudes of visitors.

Bueddefeld et al. (2023) developed learning materials, post-visit action resources, and defined interpretation outcomes for Elk Island National Park with a focus on human wildlife coexistence. Because of Covid-19 restrictions, the research team used innovative digital technology to produce an online interpretive video, with the goal of helping visitors understand how to safely co-exist with wildlife in the park. The video followed dialogic-narrative interpretation methods and four stages of the Arc of the Dialogue: (1) building community; (2) sharing personal experiences; (3) exploring experiences of others; and (4) synthesizing and bringing closure. Visitors’ knowledge increased significantly after their exposure to the video, as did their likelihood to engage in pro-environmental behaviours such as keeping a safe distance from wildlife. The interpretive video was a success and should inspire other interpreters to employ dialogic narrative storytelling and digital tools.

Hvenegaard (2017) examined the use and perceptions of interpretive programs at Miquelon Lake Provincial Park (MLPP) in Alberta. Among all visitors, 85% agreed that interpretive programs were important to the mission of AB Parks and 68% agreed that interpretive programs increased the value of their experience. Visitors participated in interpretive programs because they thought it would be good for members of their group, be entertaining, be educational, offer learning about a particular topic, and “it was something to do in the park.” Most attendees (>80%) agreed or strongly agreed that the interpretive programs helped increase knowledge about nature in MLPP, interest in attending future programs, appreciation for MLPP, and appreciation for Alberta Parks. Cook et al. (2021) expanded this study in Bow Valley Provincial Park, William A. Switzer Provincial Park, and MLPP. Visitors again reported high levels of enjoyment/satisfaction with the programs, most indicated increased knowledge and awareness of environmental topics, and almost 80% of respondents indicated positive shifts in attitudes.

In Banff National Park, Macklin et al. (2010) examined the impact of innovative interpretation (i.e., improvisational theatre games) on children’s enjoyment and perceived learning (see Hvenegaard et al., 2008). Children enjoyed improvisation theatre activities the most because they offered fun, physical activity, creativity, challenge, positive group dynamics, and novelty. However, the activities from which children learned the most were more traditional interpreter-led nature walks and talks which included sensory awareness, physical involvement, guided interaction, peer collaboration, and simple messages. Clearly, a combination of suitable approaches is needed for children.

Kath (2009) describes an education program in southern Alberta that promoted awareness of invasive species among stakeholders. The most effective component was an evening campfire program that involved handing out ‘attractive’ bouquets of invasive weeds to visitors; throughout the program, visitors were asked to throw the flowers into a fire to symbolically represent their efforts to “purge the park of its weeds” (p. 12).

Wolfe’s research (1997) highlights a few older Canadian studies. In Kananaskis Country, Alberta, an innovative poster campaign illustrating commonly picked flowers (e.g., ‘Wanted ALIVE not dead’) helped to reduce by 50% the number of visitors reprimanded by park staff for picking flowers. By providing guided interpretive hikes into the restricted area of Dinosaur Provincial Park, Alberta, the number of unauthorized visitors observed within the restricted areas decreased by nearly 90% (Wolfe, 1997).

In addition to using various theories to understand mechanisms at work within nature interpretation (Hvenegaard & Shultis, 2016), two recent systematic reviews highlight the value of interpretation and the need to continue expanding understanding and practices (He et al., 2022; Kidd et al., 2019). The need for innovative communication tools has been documented by scholars through gaps in current strategies and promising results of recent studies (He et al., 2022; Byerly et al., 2018; Kidd et al., 2019; Skibins et al., 2012). Opportunities to expand and improve interpretation practices include incorporating theory-based programming and messaging, audience segmentation, evoking affect and emotional impacts, providing post visit action resources, soliciting pledges and promises from visitors, and employing virtual and augmented reality. Both reviews indicate the need for more robust research and a focus on longitudinal outcomes of interpretation, as well a better understanding of diverse participants and their experiences. All of these ideas provide direction for the future and opportunities to improve. Here are some further insights into two topics for consideration.

Nature interpretation enhances visitor experiences and supports effective management of sites for biodiversity conservation. In spite of these benefits, nature interpretation faces many challenges. Interpretation is often underfunded, reducing its ability to achieve its goals. In many cases, an agency cuts interpretation budgets before other sectors and restores funding to interpretation well after other sectors. Interpretive staff are often relegated to seasonal and part-time positions, as opposed to permanent and full-time positions. Furthermore, many sites offering nature interpretation poorly integrate interpretation into the planning and management of the agency’s overall operations. In addition, many agencies have not been able to fully evaluate interpretation to determine cause-and-effect relationships for particular interpretive programs and techniques. Similarly, many frontline and supervisory staff are unacquainted with published research on the effectiveness of interpretation. Moreover, many site managers in charge of budgets do not have a background in, or an appreciation for, interpretation’s potential benefits.

In order to improve the benefits from and the appreciation for nature interpretation, the field has several needs. First, nature interpreters and researchers can engage in broader research, based on sound theoretical frameworks to test for the effectiveness of various techniques. Second, nature interpreters should engage in offsite educational programs to develop new bonds between nature and current and future visitors. Third, interpreters should seek to integrate their work in all aspects of a site’s operation. In fact, all site staff are and can be interpreters in some sense. Last, nature interpreters should collaborate across all interpretation and environmental sectors to increase synergies and outcomes (Ostrem and Hvenegaard 2023).

In conclusion, nature interpretation can provide visitors, tourists, recreationists, and local residents with meaningful information and experiences that will increase their awareness and understanding of the natural environment and relate these experiences to modern life. Achieving this goal will help people to have a deeper appreciation for their area’s natural and cultural heritage, desire further learning, and transfer these values and experience into their daily lives. While nature interpretation cannot be the only mechanism to transform people into engaged and caring citizens, interpretation—and the related techniques of environmental education and tour guiding—appears to be the best approaches we have for making such substantial changes at the individual and societal level in protected areas.

Alberta Parks. (2016). Alberta parks quick facts. Alberta Environment and Parks.

Alberta Parks. (2018). 50 years of Interpretation in Alberta Parks (unpublished report by Keith Bocking). Alberta Parks.

Ballantyne, R., Packer, J., Hughes, K., & Gill, C. (2018). Post-visit reinforcement of zoo conservation messages: The design and testing of an action resource website. Visitor Studies, 21(1), 98–120.

Blye, C., Hvenegaard, G., & Halpenny, E. (2023). Are we creatures of logic or emotions? Investigating the role of attitudes, worldviews, emotions, and knowledge gain from environmental interpretation on behavioural intentions of park visitors. Journal of Outdoor Recreation, Education, and Leadership, 15(1), 9–28.

Bueddefeld, J., Ostrem, J., Murphy, M., Maraj, R., & Halpenny, E. (2023). Lessons for becoming bison wise and bear aware in Elk Island National Park. Human Dimensions of Wildlife, Online 1–19.

Byerly, H., Balmford, A., Ferraro, P. J., Hammond Wagner, C., Palchak, E., Polasky, S., Ricketts, T. H., Schwartz, A. J., & Fisher, B. (2018). Nudging pro-environmental behavior: evidence and opportunities. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 16(3), 159–168.

Cook, K. J., Hvenegaard, G. T., & Halpenny, E. A. (2021). Visitor perceptions of the outcomes of personal interpretation in Alberta’s Provincial Parks. Applied Environmental Education & Communication, 20(1), 49–65.

Federation of Alberta Naturalists. (2005). Fish, fur & feathers: Fish and wildlife conservation in Alberta, 1905-2005. Fish and Wildlife Historical Society.

Gilson, J. (2020) Inspired to inspire: Holistic inspirational interpretation. Tortuga Creative Studio.

Government of Alberta. (2009). Plan for parks 2009-2019. Alberta Parks. Retrieved from https://www.albertaparks.ca/media/123456/p4p.pdf

Government of Canada. (1990). National Parks Act. Minister of Supply and Services Canada.

Ham, S., & Weiler, B. (2007). Isolating the role of on-site interpretation in a satisfying experience. Journal of Interpretation Research, 12(2), 5–24.

Harkin, J.B. 1957. The history and meaning of the national parks of Canada. H. R. Larson Publishing Company.

He, M., Blye, C. J., & Halpenny, E. (2022). Impacts of environmental communication on pro-environmental intentions and behaviours: A systematic review on nature-based tourism context. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 31(8), 1921–1943.

Hvenegaard, G. T. (2017). Visitors’ perceived impacts of interpretation on knowledge, attitudes, and behavioural intentions at Miquelon Lake Provincial Park, Alberta, Canada. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 17(1), 79–90.

Hvenegaard, G., Johnson, P., & Macklin, K. (2008). Improvisational theatre games to engage children. The Interpreter, 4(2), 6–8.

Hvenegaard, G. & Shultis, J. (2016) Interpretation in protected areas. In P. Dearden, R. Rollins, & M. Needham (Eds.), Parks and protected areas in Canada: Planning and management (pp. 141-169). Oxford University Press Canada.

Hvenegaard, G., Olson, K., & Halpenny, E. (2023). Direction for interpretive programming from Alberta Provincial Park management plans. Parks Stewardship Forum, 39(1), 91–100.

Interpretation Canada. (1976). About Interpretation Canada. Retrieved from https://interpretationcanada.wildapricot.org/about

Kath, D. (2009). Botanical pollution: Report on a pilot invasive species education program. InterpScan, 32(4), 11–12.

Kidd, L. R., Garrard, G. E., Bekessy, S. A., Mills, M., Camilleri, A. R., Fidler, F., Fielding, K. S., Gordon, A., Gregg, E. A., Kusmanoff, A. M., Louis, W., Moon, K., Robinson, J. A., Selinske, M. J., Shanahan, D., & Adams, V. M. (2019). Messaging matters: A systematic review of the conservation messaging literature. Biological Conservation, 236, 92–99.

Killan, G. (1993). Protected places: A history of Ontario’s Provincial Parks System. Dundurn Press Ltd. in association with the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources.

Lee, W. H., & Moscardo, G. (2005). Understanding the impact of ecotourism resort experiences on tourists’ environmental attitudes and behavioural intentions. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 13, 546–65.

MacDonald, E., Milfont, T., & Gavin, M. (2016). Applying the Elaboration Likelihood Model to increase recall of conservation messages and elaboration by zoo visitors. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 24(6), 866–881.

Macklin, E. K., Hvenegaard, G. T., & Johnson, P. E. (2010). Improvisational theater games for children in park interpretation. Journal of Interpretation Research, 15(1), 7–13.

Mann, J. B., Ballantyne, R., & Packer, J. (2018). Penguin Promises: encouraging aquarium visitors to take conservation action. Environmental Education Research, 24(6), 859–874.

Ostrem, J., & Hvenegaard, G. T. (2023). Interagency collaboration for environmental education: Insights from the Beaver Hills Biosphere, Canada. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, online.

Powell, R., Kellert, S. R., & Ham, S. H. (2009). Interactional theory and the sustainable nature-based tourism experience. Society and Natural Resources, 22, 761–76.

Powell, R. B., Vezeau, S. L., Stern, M. J., Moore, D. W. D., & Wright, B. A. (2018). Does interpretation influence elaboration and environmental behaviors? Environmental Education Research, 24(6), 875–888.

Randall, C., & Rollins, R. (2006). The kayak tour guide: An important influence on national park visitors. InterpScan, 31(4), 5–9.

Skibins, J., Powell, R. & Stern, M. (2012). Exploring empirical support for interpretation’s best practices. Journal of Interpretation Research, 17(1), 25–44.

Stern, M. J., Powell, R. B., & Hockett, K. S. (2011). Why do they come? Understanding attendance at ranger-led programs in Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Journal of Interpretation Research, 16(2), 35–52.

Stern, M. J., & Powell, R. B. (2020). Taking stock of interpretation research: Where have we been and where are we heading? Journal of Interpretation Research, 25(2), 65–87.

Tilden, F. (1977). Interpreting our heritage, 3rd ed. University of North Carolina Press.

Tubb, K. N. (2003). An evaluation of the effectiveness of interpretation within Dartmoor National Park in reaching the goals of sustainable tourism development. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 11, 6: 476–98.

Weaver, D. B. (2002). The evolving concept of ecotourism and its potential impacts. International Journal of Sustainable Development, 5(3), 251–264.

Whitburn, J., Linklater, W., & Abrahamse, W. (2020). Meta-analysis of human connection to nature and proenvironmental behavior. Conservation Biology, 34(1), 180–193.

Wolfe, R. (1997). Interpretive education: An under-rated element of park management? Research Links, 5(3), 11–12.

Glen T. Hvenegaard

University of Alberta

Glen Hvenegaard is a Professor of Environmental Science at the University of Alberta Augustana Campus in Camrose, Alberta. He researches human-nature interactions, focusing on interpretation, parks, birds, nature-based tourism, and rural sustainability. He is co-editor of Parks and Protected Areas: Mobilizing Knowledge for Effective Decision-Making (2021) and Tourism and Visitor Management in Protected Areas: Guidelines for Sustainability (2018).

Clara-Jane Blye

Dalhousie University

Clara-Jane Blye is a Recreation Management faculty member at Dalhousie University. Her research is focused on outdoor recreation policy, park management, environmental psychology, and connections to nature. She uses mixed methods in her research and has a strong applied focus to her work. She has worked with NGO’s and park agencies to develop theoretical and practical research that informs policies and strategies. Currently, she is studying experiences of New Canadians visiting Elk Island National Park.

Elizabeth Halpenny

University of Alberta

Elizabeth Halpenny works at the University of Alberta’s Faculty of Kinesiology, Sport, and Recreation. She teaches and conducts research in the areas of tourism, marketing, environmental psychology and protected areas management. Her research focuses on visitor experiences and environmental stewardship. Current projects include: recreational use and stewardship of natural areas; agritourism; and tourism-related social media conservations about climate change. She received her PhD in Recreation and Leisure Studies from the University of Waterloo in 2006.

Nature Interpretation Copyright © 2024 by Glen T. Hvenegaard; Clara-Jane Blye; and Elizabeth Halpenny is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

4

A holiday offers a break from the routine of everyday life. For some people, the best kind of break involves the luxury and relaxation offered by a beach-side resort or a Caribbean cruise. For others, it involves an educational experience or a cultural immersion. And for many others, the best kind of holiday is one that is steeped in adventure. Not surprisingly, the commercial tourism industry has adapted over the last several decades to cater to the needs and desires of travellers searching for adventurous experiences.

People have different ideas of what makes an ideal adventure experience, and the adventure tourism sector of the global tourism industry is correspondingly diverse, offering everything from short parasailing excursions and bungee jumps to multiday river expeditions and guided ascents of Mount Everest. This diversity of offerings reflects, in part, the impressive overall size and continued growth of the global adventure tourism sector. In 2014, the adventure tourism market was estimated to be worth USD 263 billion (UNWTO, 2014). It exceeded USD 900 billion in 2020 and it is expected to reach USD 1.16 trillion by 2028 (ATTA, 2020).

The economic potential of adventure tourism is significant. Adventure tourists tend to spend more money on their adventure experiences than other tourists do on their travels and activities (ATTA, 2022). However, as global competition in this lucrative market increases, Canada is at risk of falling behind. According to the Adventure Tourism Development Index (2020), Canada ranks seventh globally among developed countries with strong potential for adventure tourism competitiveness. However, since 2016, it has fallen in its ranking in the top potential destinations for adventure travellers. New government initiatives like the Federal Tourism Growth Strategy and other provincial and municipal equivalents aim to correct this decline by increasing public and private investment in the Canadian tourism industry. The main objective of these strategies is to unleash tourism’s potential to drive economic growth and job creation in all regions of the country. As one of the most lucrative and fastest-growing sectors of the global tourism industry, the adventure tourism sector will play an important role in the continued growth of Canada’s tourism industry.

This chapter provides some context for understanding these recent developments. It begins with a brief discussion of what adventure tourism is and how it developed as a unique sector of the tourism economy. This is followed by a short section describing the current adventure tourism landscape in Canada and another that summarizes some of the challenges and issues the adventure tourism sector and individual operators across the country are currently facing.

There are multiple and competing definitions of adventure tourism. Most are exceedingly broad and do very little to define precisely what adventure tourism is or what it involves. For example, Destination BC, the destination marketing organization for the province of British Columbia, defines adventure tourism as “activities that present the participant with risk and challenge” (Destination BC, 2014, p. 1). They divide these activities into two broad categories: hard and soft adventure. Hard adventures like whitewater rafting and heli-skiing require more experience, better physical fitness, and a greater degree of risk and challenge than soft adventures like wildlife viewing or gondola rides. Although risk and challenge are essential components of the adventure experience, they do not in themselves adequately explain nor define what adventure tourism is and what it involves.

The Adventure Travel Trade Association (ATTA), a global lobby group for the adventure travel industry, offers another broad definition of adventure tourism. According to the ATTA, adventure tourism involves “a trip that includes at least two of the following three elements: physical activity, natural environment, and cultural immersion” (UNWTO, 2014, p. 10). While this definition requires that only two of the three components be experienced, trips incorporating all three tend to afford tourists the fullest adventure experience—for example, a trip to Peru that involves trekking (physical activity) on the Machu Picchu trail (natural environment) and genuine interaction with local residents and/or indigenous peoples (cultural immersion). However, based on the ATTA’s definition of adventure tourism, a walking tour (physical activity) of ancient architectural ruins in Rome (cultural immersion) would fall under the label of adventure tourism.

Working towards a more precise definition of adventure tourism requires first clarifying what tourism is and how different forms of tourism are categorized. Tourism generally involves the commercial organization and operation of travel for purposes of leisure and business. The tourism industry consists of five operating sectors: accommodation; transportation; food and beverage; travel services; and attractions, entertainment, and recreation (Goeldner & Ritchie, 2011). The attractions, entertainment, and recreation sector is itself comprised of five individual categories of “things to do”: cultural attractions (i.e., museums, art galleries, archaeological sites, etc.), natural attractions (i.e., national parks, beaches, northern lights, etc.), events (i.e., festivals, sports events, trade shows, etc.), recreation (i.e., golfing, hiking, sightseeing, etc.), and entertainment (i.e., theme parks, shopping malls, casinos, etc.). These categories are often used to define the type of tourism the tourist is participating in. For example, a golfing holiday may be labelled as “golf tourism,” a visit to a music festival as “festival tourism,” and a wine-tasting tour as “culinary tourism.” Based on this method of classification, adventure tourism involves a combination of recreational activities and natural attractions; or, more precisely, the commercial organization and operation of guided and non-guided tours and activities where the principal attraction is an adventurous form of outdoor recreation (Hudson, 2003; Buckley, 2006; Varley, Taylor, & Johnson, 2013; Huddart & Stott, 2020).

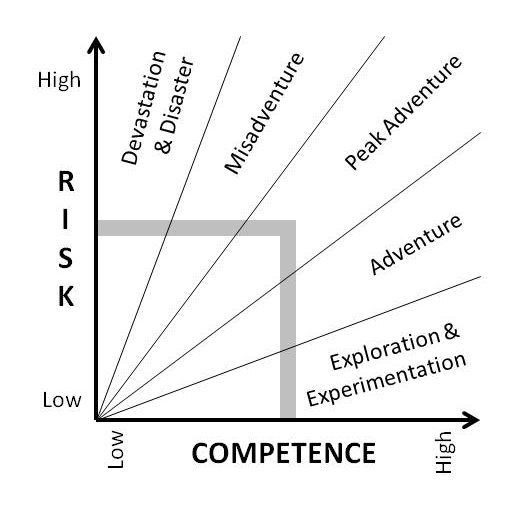

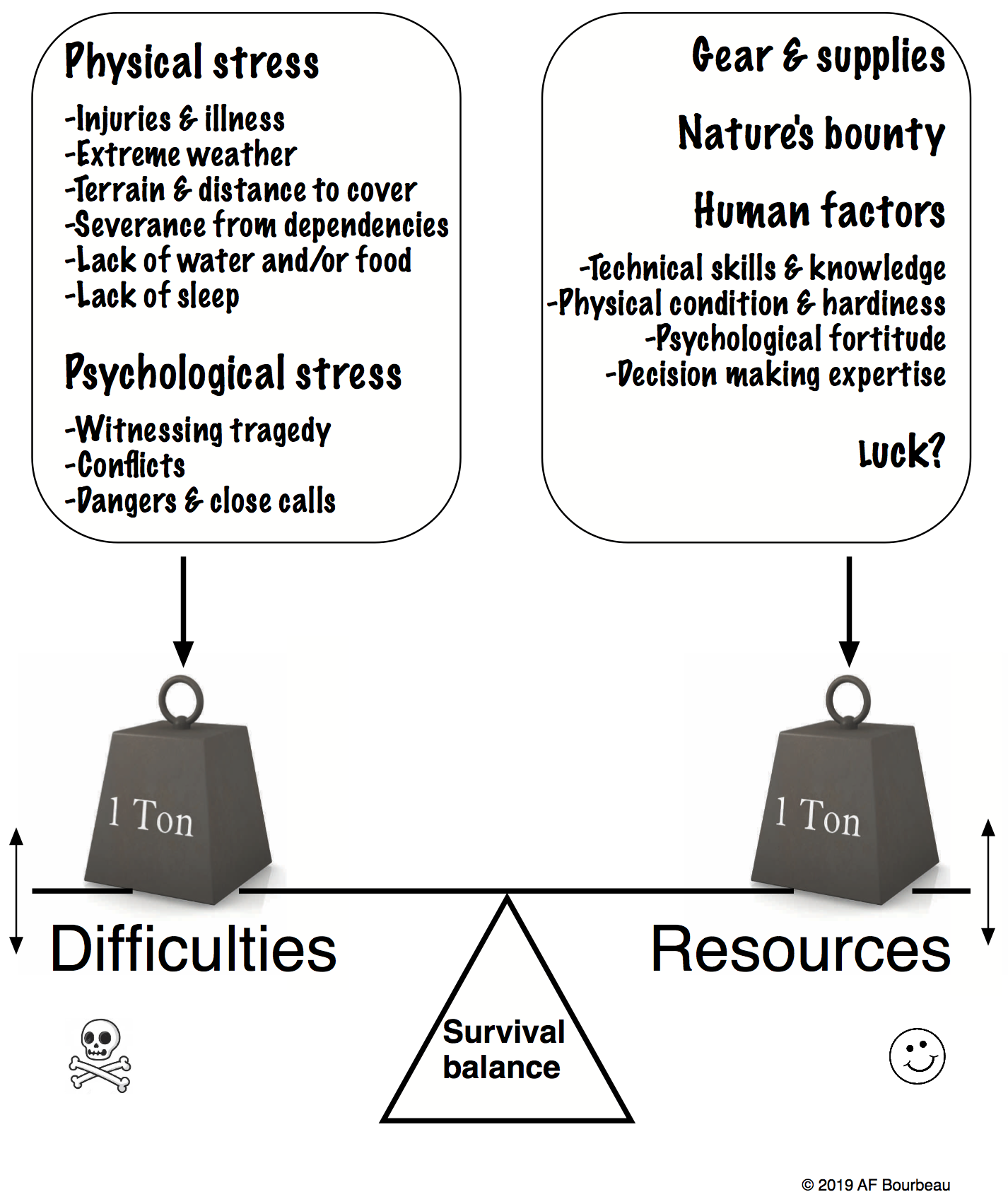

Set against a natural and scenic backdrop, outdoor recreational activities like hiking, dog sledding, whitewater rafting, jet boating, sea kayaking, skiing, and mountaineering provide adventure tourists with an “extraordinary” experience (Priest, 1990; Varley, 2013). The outdoor adventure experience tends to elicit a strong emotional response in the form of the excitement and thrills that accompany an activity like tandem skydiving, or the peace and serenity that go along with kayaking on a calm and picturesque river or lake. What makes outdoor recreational activities adventurous is the heightened level of risk the participants and providers assume (Krein, 2007).

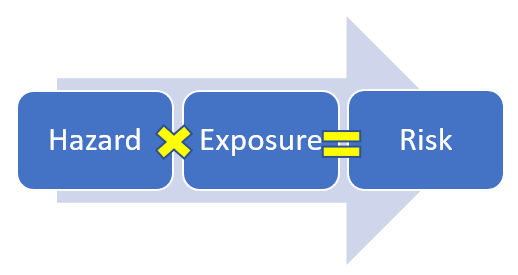

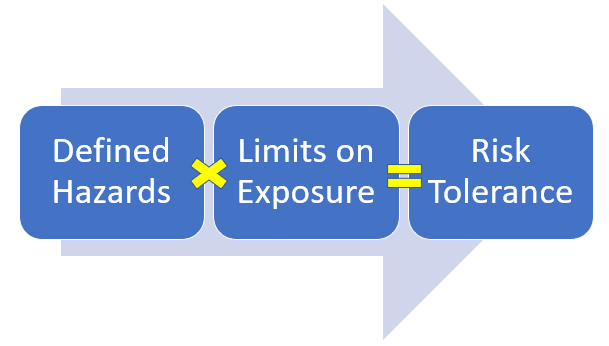

Risk involves the natural, human, and operational hazards associated with the delivery of a particular adventure product, as well as the perceived risk, or sense of danger felt by the participant. Some adventure products, like a mountaineering trip or a whitewater kayaking excursion, are inherently risky because of the hazards associated with taking tourists up remote mountains or down wild rivers. Activities like bungee jumping and canyon swinging are among the safest adventure activities because of the controlled environment in which they are offered. In the case of so-called “extreme” activities, such as tandem skydiving, the degree of perceived risk is often much greater than the actual risk involved. Whether real or perceived, however, risk must be managed, mitigated, and manipulated by the operator and guide in a way that enables the tourist to feel both safe and in danger (Holyfield, 1999; Fletcher, 2010; Urry, 2013).

The popularity of an adventure tourism product is inversely related to its level of difficulty (Buckley, 2007). The most popular commercial adventure activities by volume of participants are unskilled, low-risk, group-based tours that take place in accessible adventure destinations like Whistler, British Columbia, Banff, Alberta, and Mont Tremblant, Quebec. Conversely, as the technical difficulty and the level of prerequisite experience needed for an activity increases and the location becomes more remote, the product tends to be riskier, costlier, and of a longer duration. For example, a zipline tour in Whistler with Ziptrek Ecotours requires no prerequisite skill, lasts about two hours, takes place in large groups multiple times per day, and costs about CAD 200 per person. In contrast, a canoe trip down the Thelon River in Nunavut with Jackpine Paddle requires some paddling skill, lasts about two weeks, takes place in small groups only once or twice per summer, and costs more than CAD 10,000 per participant. Not surprisingly, more people go ziplining in Whistler in a single afternoon than descend the Thelon River in an entire summer.

Adventure tourism was not recognized as a distinct sector of the global tourism industry until the early 1990s, but its historical roots reach back over two centuries. In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, a new way of looking at and appreciating wild nature emerged out of the Romantic movement in Europe. Rather than being seen as something to be tamed or cultivated, wild landscapes became places of great natural beauty and playgrounds for the European leisure class. Mountain villages like Chamonix, in France, developed into popular tourist destinations as visitors flocked to see the Mont Blanc massif and walk on the fabled Mer de Glace glacier. This new interest in wild and sublime nature spilled over into North America, where a version of the Grand Tour that was so popular among the European elite took hold. The Adirondack Mountains, the St. Lawrence River Valley, Niagara Falls, and the Algonquin Highlands became popular tourist destinations along the expanding railway network in eastern North America (Jasen, 1995).

The nature-based tourism frontier expanded into western Canada with the completion of the Canadian Pacific Railway in 1885. The CPR built luxurious hotels in newly established national parks like Banff (the Rocky Mountains) and Glacier (the Columbia Mountains), and it even hired a team of mountain guides from Switzerland to lead Canadian and international visitors on hiking and climbing tours throughout the mountain parks (Hart, 1983; Robinson & Slemon, 2016). Additional guiding and outfitting services developed in and around other popular and accessible tourist destinations across the country, such as the Temagami and Algonquin regions of central Ontario, but a fully formed nature-based tourism industry would not emerge in Canada until after the Second World War.

In the 1950s and 1960s, outdoor leisure pursuits gained increased popularity across a much broader demographic in Canada. The post-war period brought an unprecedented degree of personal prosperity and freedom to many Canadians: the economy was booming; new technologies and labour laws provided Canadians with more leisure time; and the automobile provided a greater degree of mobility than ever before. Consequently, Canadians started to spend more of their free time in search of leisure and adventure outside of the city. An “outdoor recreation boom” swept across Canada’s urban centres, creating a nationwide demand for “recreational resources” like national and provincial parks, campgrounds, motels, ski resorts, wilderness resorts, and guiding and outfitting services (Killan, 1993; Wilson, 1991).

Federal and provincial authorities responded to the increased demand for nature-based travel and tourism services and infrastructure by expanding the provincial and national parks systems and by dedicating more funds to tourism development and marketing. The private sector responded with the establishment of guiding and outfitting services. Many of Canada’s most successful adventure tourism outfitters to date were established in the wake of the post-war outdoor recreation boom, companies like Canadian Mountain Holidays, Mike Wiegele Helicopter Skiing, Yamnuska Mountain Adventures, Canadian River Expeditions, Blackfeather Adventures, and Wilderness Tours.

Since the 1970s, the adventure tourism sector has developed with relatively little support and intervention by federal and provincial authorities in Canada. The expansion of the provincial and national parks systems facilitated the growth of private and commercial forms of outdoor recreation across the country. However, unlike in New Zealand, where federal authorities guided the development of that country’s adventure tourism sector, federal and provincial authorities in Canada have taken more of a hands-off approach. Consequently, the Canadian adventure tourism sector is mostly self-regulated. Rather than abiding by a set of federal regulations and safety guidelines, Canadian operators tend to set their own safety standards, best practices, and certification processes, often in conjunction with trade associations like the British Columbia River Outfitters Association or guiding organizations like the Association of Canadian Mountain Guides and Aventure Ecotourisme Quebec. The trouble with this general lack of federal and provincial oversight is that it produces a wide degree of variance in the quality of adventure tourism experiences across the country, as well as in the calibre and training of guides working in the sector. Both have potentially dangerous ramifications for properly protecting people and the environment from harm.

Despite the lack of government oversight and Canada’s recent descent in the world rankings table, the adventure tourism sector in Canada is thriving. However, supporting this statement with economic statistics is challenging. Not every province and territory in Canada differentiates between traditional tourism and adventure tourism spending. Further complicating the matter is the fact that different definitions of adventure tourism are used to estimate or calculate the economic impact of the sector. Calculations that include revenues generated from private travel for purposes of outdoor recreation will inevitably be greater than those calculations that focus exclusively on commercial adventure tourism activities. Global estimates of the value of the adventure tourism sector (see above) tend to include all independent travel related to private or commercial outdoor recreation activities, revenues from packaged adventure tours, revenues associated with fixed-site adventure activities (i.e., ski resorts), and most of the revenues generated by ancillary businesses linked to adventure tourism, such as recreational equipment, adventure-branded clothing and apparel, and a significant proportion of the amenity-migrant property market (Buckley, 2010). This formula has not yet been applied to calculations of the value of the adventure tourism sector in Canada. However, provincial authorities in British Columbia have used a similar formula to calculate the value of their adventure tourism economy. The last sector-wide study in BC found that annual adventure tourism revenues exceeded CAD 1.2 billion. Those revenues supported 2,200 businesses and more than 21,000 employees (Destination BC, 2014).

The success of adventure tourism in BC has much to do with the province’s unique physical geography. A long coastline, multiple ranges of snow-capped mountains, hundreds of wild rivers and lakes, dense forests, and an abundance of wildlife make it an ideal destination for travellers seeking adventurous experiences. What’s more, BC’s geography and climate also provide the optimum natural conditions for practicing many outdoor recreational activities, such as skiing, snowboarding, mountain biking, hiking, mountaineering, rock climbing, surfing, paddle boarding, sea kayaking, white water kayaking, and rafting. In fact, the natural conditions in BC are so optimal for many of these activities that the province is often ranked by many travel publications as one of the best adventure tourism destinations on the planet.

Not surprisingly, many of Canada’s so-called “adventure capitals” are situated in British Columbia. Adventure capitals are popular destinations that offer a wide variety of skilled and unskilled adventure tours throughout the year. The mountain towns of Whistler, Squamish, and Revelstoke, along with the coastal communities of Tofino and Ucluelet, are among the most popular adventure capitals in Canada. Other Canadian adventure capitals include Banff and Jasper in Alberta, Waskesiu Lake in Saskatchewan, the Muskoka, Temagami, the Algonquin regions of central Ontario, and Mont Tremblant, Quebec. Access to these popular adventure destinations is made relatively easy by their proximity to metropolitan centres and busy international or regional airports.

The economic success and popularity of Canada’s adventure capitals have encouraged other popular tourism destinations to either rebrand themselves as adventure destinations or make a more concerted effort at marketing to adventure travellers. For instance, over the last decade or so, Niagara Falls, Ontario, one of the oldest and most popular tourist destinations in Canada, has rebranded itself as an adventure tourism destination. In addition to its featured natural attractions, casinos, wineries, and theme parks, the City of Niagara Falls and the greater Niagara region now offer popular adventure activities like jet boating, ziplining, and tandem skydiving. Further east, the province of Nova Scotia recently started to market itself as a four-season adventure destination, boasting a wide range of adventure tour products from surfing, cycling, whale watching, and tidal-bore rafting, to cross-country and downhill skiing, snowmobiling, and ice-fishing. Similar rebranding and marketing efforts are being embraced by municipalities, provinces, and territories across the country.

Now that federal, provincial, and territorial governments in Canada have recognized the economic potential of the adventure tourism sector, it is safe to assume that the sector will continue to grow into the future. Despite a positive outlook, though, the sector faces many challenges. This concluding section of the chapter highlights four main challenges facing the sector today. Some of these challenges are common to adventure tourism globally, and some are unique to the Canadian context.

The adventure tourism sector in Canada must contend with several human resource challenges. Adventure tour operators have been dealing with staffing shortages, underqualified guides, and high staff turnover rates since long before the economic implications of the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated these issues. Low wages and seasonal work factor into the high rate of staff turnover. Many adventure guides search for “real jobs” after only a couple of summer or winter seasons working in the sector. Those who persevere for more than a couple of years are the ones who piece together year-round work, either by alternating between summer and winter seasons in the same location or by heading to an international destination to find employment in the off-season. High staff turnover rates cost operators time and money in terms of hiring and training. Further complicating matters is the recent decline in enrolment in, or outright closure of, many post-secondary leisure and recreation programs in Canada. These developments have decreased the number of qualified applicants for adventure tourism jobs in Canada so much that some employers have turned to migrant labour pools to fill vacant positions. Staff training and retention are now extremely high priorities for most adventure tour operators in Canada.

Another human resource issue facing the adventure tourism sector in Canada involves the workplace culture associated with adventure tourism. The adventure tourism workplace has long been a space dominated by white men. Women have struggled over the years to gain a foothold in this highly masculine and sometimes misogynistic environment. So too have Indigenous peoples and other racial and ethnic minorities. While many industries have adopted hiring practices and other workplace policies to promote equity, diversity, inclusivity, and decolonization, the adventure tourism sector in Canada continues to lag. Of course, many companies are in the process of changing their workplace cultures by incorporating equity, diversity, inclusion, and decolonization principles into their organizational policies and daily practices, but much work still remains.

One challenge that has long plagued the adventure tourism sector is the threat of over-use, or over-tourism, at popular sites. This problem is often called the paradox of nature-based tourism. The more popular a natural place becomes, the more likely it will suffer environmental degradation; the more environmental degradation a place suffers, the less popular it becomes. Sustainably developing adventure tourism sites has long been a sector priority, but the problem has become compounded in recent years by the digitization of modern life and the rise of social media. Adventure tourists increasingly rely on social media to inform their travel and destination choices. A single photo on Facebook or Instagram, or a captivating tweet can offer sudden inspiration for travel and adventure. Yet, for as much as social media benefits the adventure tourism economy, it can also lead to unsustainable growth and environmental degradation as visitors flock to the latest “Instagrammable” site. Take, for example, Joffre Lakes Provincial Park in British Columbia, which features a spectacular trio of alpine lakes surrounded by snow-capped peaks and hanging glaciers. In 2015, the park experienced a 250% increase in visitation after some tourists’ photographs of the scenery went viral (de l’Église, 2019). The subsequent flood of visitors left litter and caused trail erosion. To mitigate these impacts, BC Parks revamped the hiking trail system, making it much more accessible to visitors, and, in turn, further transforming what used to be a “hidden gem” into a crowded tourist attraction. This is one reason why sustainable tourism development of any kind requires careful planning and much forethought.

A list of the challenges currently facing the adventure tourism sector cannot be complete without mentioning the climate crisis. Global heating is affecting the entire planet: sea levels are rising; weather patterns are changing; glaciers and polar ice caps are melting; coral reefs are being bleached; forest fires and hurricanes are becoming more frequent and intense; and the list goes on. Adventure tourism operators are not immune to the impacts of climate change. Warming temperatures in the Arctic and rapidly receding polar sea ice have negatively impacted polar bear tourism in Churchill, Manitoba, the polar bear capital of Canada. Warmer winters with less snowfall have taken a toll on Canada’s skiing and snowboarding sector, especially in British Columbia and Alberta. More intense and longer forest fire seasons in western Canada have limited the operating field of many regional rafting, hiking, and canoeing outfitters. Melting glaciers and warmer temperatures in the mountains have added a new level of risk to climbing and mountaineering operations in the Western Cordillera as terrain instability has increased the frequency of rockfalls in the summer and avalanches in the winter. Despite these challenges, the future of adventure tourism in Canada remains bright. As much as the effects of the climate crisis are negatively impacting the adventure tourism sector in Canada, they are also providing some new opportunities for operators and tourists. The most significant opportunity is the extension of the summer tourist season into the spring and autumn months, especially in the far northern parts of the country where frigid temperatures have long hindered tourism development. Public and private investment in adventure tourism is on the rise. So too is the percentage of tourists participating in outdoor adventure activities. The sector is already well established in provinces like British Columbia, Ontario, and Quebec, and there is plenty of room for sector expansion, not only in and around major urban centres but also in more remote and rural areas across the country, particularly in the near and far north. As domestic and international tourists continue to seek out adventurous experiences, the adventure tourism sector in Canada will continue to grow.

Adventure Travel Trade Association. (2015). Industry snapshot. https://learn.adventuretravel.biz/research/

Adventure Travel Trade Association. (2020). Adventure tourism development index. https://learn.adventuretravel.biz/research/

Adventure Travel Trade Association. (2022). Adventure travel industry snapshot, May 2022. https://learn.adventuretravel.biz/research/

Buckley, R. (2006). Adventure tourism. CAB International.

Buckley, R. (2007). Adventure tourism products: price, duration, size, skill, remoteness. Tourism Management, 28 (6), 1428-33.

Buckley, R. (2010). Adventure tourism management. Elsevier.

de l’Église, J. (2019). Spoils of #nature on Instagram. Beside. https://beside.media/dossier/spoils-of-nature-on-instagram/

Destination British Columbia. (2014). Tourism sector profile: Outdoor adventure. https://www. destinationbc.ca/content/uploads/2018/05/Tourism-Sector-Profile_OutdoorAdventure_May2014.pdf

Destination Canada. (2021). Tourism outlook: Forecast highlights fall 2022. https://www.destinationcanada.com/en/research#featuredreports

Fletcher, R. (2010). The emperor’s new adventure: public secrecy and the paradox of adventure tourism. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 39 (1), 6-33.

Goeldner, C.R., & Ritchie, J.R.B. (2011). Tourism: principles, practices, philosophies (12th Ed.). John Wiley & Sons.

Hart, E.J. (1983). The selling of Canada: the CPR and the beginning of Canadian tourism. Altitude Publishing Ltd.

Holyfield, L. (1999). Manufacturing adventure: the buying and selling of emotions. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 28 (1), 3-32.

Huddart, D., & Stott, T. (2020). Adventure tourism: environmental impacts and management. Palgrave Macmillan.

Hudson, S., (Ed.). (2012). Sport and adventure tourism. Taylor & Francis.

Jasen, P. (1995). Wild things: nature, culture, and tourism in Ontario, 1790-1914. University of Toronto Press.

Killan, G. (1993). Protected places: a history of Ontario’s provincial parks system. Dundurn & Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources.

Krein, K. (2007). Nature and risk in adventure sports. In M. McNamee (Ed.), Philosophy, risk and adventure sports, 80-93. Routledge.

Priest, S. (1990). The adventure experience paradigm. In J.C. Miles & S. Priest (Eds.), Adventure education (pp. 157-62). Venture Publishing.

Robinson, Z., & Slemon, S. (2016, May). Hard times in the Canadian Pacific Rockies. Canadian Rockies Annual, 1, 64-73.

Statistics Canada. (2021, March 31). National tourism indicators, fourth quarter 2020. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/210331/dq210331b-eng.htm

Tam, S., Sood, S., & Johnston, C. (2021, June 8). Impact of COVID-19 on the tourism sector, second quarter of 2021. Statistics Canada. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/45-28-0001/2021001/article/00023-eng.htm

United Nations World Tourism Organization. (2014). Global report on adventure tourism. https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/book/10.18111/9789284416622

Urry, G. (2013). Pushing life to the edge of life: the ability of adventure to take the individual into the world. In P. Varley, S. Taylor, & T. Johnson (Eds.), Adventure tourism: meaning, experience, and learning (pp. 47-61). Routledge.

Varley, P. (2013). Confecting adventure and playing with meaning: the adventure commodification continuum. Journal of Sport & Tourism, 11 (2), 173-94.

Varley, P., Taylor, S., & Johnson, T., (Eds.). (2013). Adventure tourism: meaning, experience, and learning. Routledge.

Wilson, A. (1991). The culture of nature: North American landscape from Disney to the Exxon Valdez. Between the Lines.

Robert Vranich

University of Alberta

Robert Vranich is a PhD candidate in the Faculty of Kinesiology, Sport, and Recreation at the University of Alberta. His research examines the history of outdoor recreation, nature-based tourism, and wilderness preservation in Canada.

Jerry Isaak

Thompson Rivers University

Jerry Isaak is an Associate Teaching Professor and program lead for ski touring in the Adventure Studies Department at Thompson Rivers University. His research interests lie in avalanche education, decision-making in extreme environments, and the pedagogy of educational expeditions within higher education.

James Rodger

Thompson Rivers University

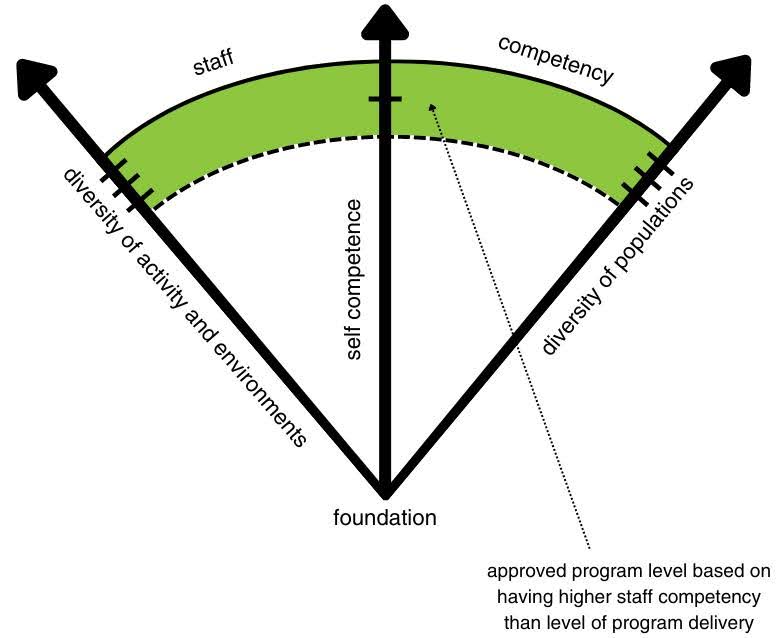

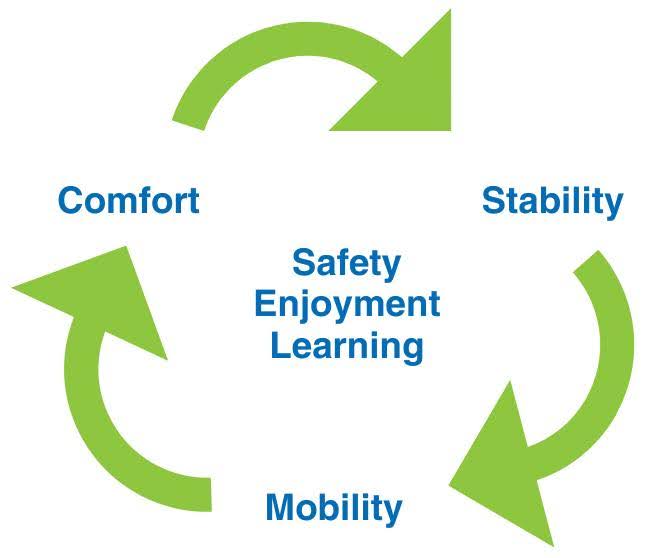

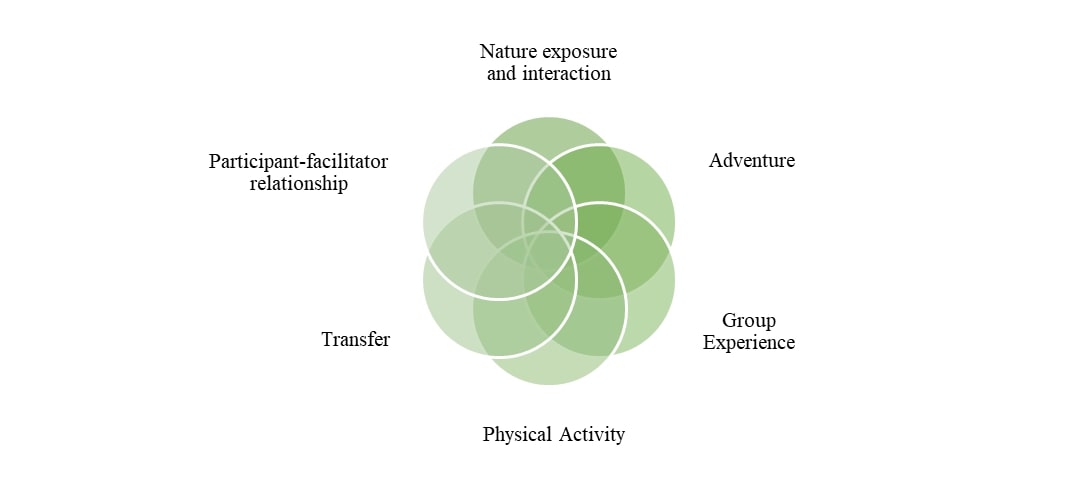

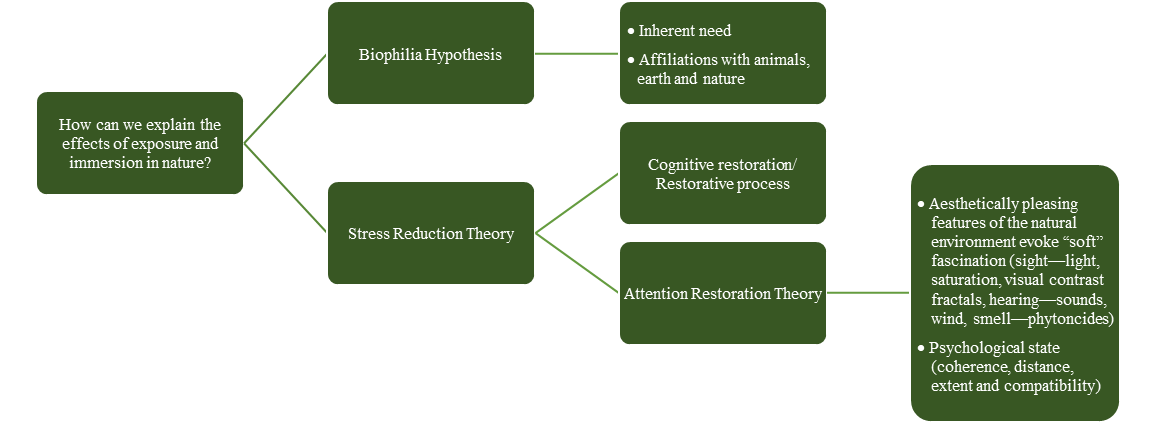

James Rodger is an Assistant Teaching Professor and Program Coordinator for the Adventure Studies Program at Thompson Rivers University. James focuses on the adventure industry and accessibility. His interests and professional orientation are river recreation, diversity in adventure, and risk management. He continues to teach swift water rescue and rafting. He actively guides in Canada and internationally.