Applying Tactics to Develop Strategy: Envisioning the Future of Higher Education

Applying tactics to develop strategy: envisioning the Future of Higher Education

Meghan E. Norris1 and Steven M. Smith2

1Queen’s University

2Saint Mary’s University

Introduction

Have you ever watched children learning to play soccer or hockey? They tend to all chase the ball or puck, with everyone chasing that thing which is most salient for them: the thing that everyone wants. The thing that will score a goal. Experienced players know that chasing the ball or puck is not the best strategy to scoring a goal, however. You don’t go where the puck is….you go where the puck is going. Taking this perspective allows us to understand that there is always a broader lens that needs to be used to properly envision and achieve the goal.

Just as in sports, successful approaches to higher education require the development and implementation of a more comprehensive strategy. Chasing a “thing,” such as enrolment targets, a new program, CRM software implementation, although salient and satisfying in the immediate, are alone unlikely to win the long game. Institutions, and individuals, need to take a comprehensive approach to higher education: supporting the academic mission by recruiting students, faculty, and staff, and then actively developing and promoting their skills and talent, nurturing their next steps whatever they may be.

What then is the academic mission? Academic missions vary by institution type and location. For example, some institutions are research-forward, providing substantial support to basic and applied science and discovery. Some institutions are teaching-forward with less focus on discovery and more on developing students in their respective areas of study. Other institutions may have explicit expectations of supporting their surrounding communities through various types of programming, such as extension programs found in land-grant institutions in the United States. Of course, many institutions carry a mix of these mandates and more. Thus, the path to supporting academic missions can, and should, vary depending on the needs of a given institution.

An important question arises: why should we care about higher education? Higher education is expensive. In Canada, undergraduate students spend an average of $6,693 CAD each year in tuition alone (Statistics Canada, 2021a), approximately half of graduating undergraduate students have debt, with the average debt being approximately $20,000 CAD (Statistics Canada, 2020), and pursuing higher education requires a significant investment of time. That said, there are many benefits to higher education, also supported by data from Statistics Canada (e.g., Statistics Canada, 2021b). To highlight a few:

- Higher education continues to be associated with higher income (see Statistics Canada, 2024)

- The majority of students who pursue higher education report being happy with their jobs (Statistics Canada, 2019)

- Higher levels of education and income are associated with longer lives, with more time spent in good health (Bushnik et al., 2020)

These trends are not just Canadian. For example, pulling on data from the United States, in 2022, the employment rate is higher for those with post-secondary (87% of those with a bachelor’s degree or higher were employed, versus 61% of those who had not completed high school) (National Centre for Education Statistics, 2023).

It is important that we recognize that the benefits of post-secondary extend beyond the individual students who attend, and benefits are greater than employment alone. There are many societal benefits associated with post-secondary including significantly increased civic engagement as demonstrated by increased likelihood to vote (Uppal & LaRochelle-Côté, 2016), increased rates of volunteering and charitable giving (e.g., DeClou, 2014) and increased rates of blood donation (Baum & Paea, 2005). Post-secondary institutions also play a critical role in the Canadian research landscape (e.g., Industry Canada, 2001), develop future highly skilled professionals such as health care workers, provide community access to libraries and scholarly talks, support community engagement activities, offer recreation events and space, and more. Colleges and universities are also important economic contributors to their communities, employing 410,000 people in Canada and generating $40 billion in direct expenditures in 2021 (and much more in indirect expenditures) (Universities Canada, 2024). Similarly, over 3.6 million people worked in post-secondary education in the US in 2023 (Lederman, 2024).

Given the many benefits associated with post-secondary, the wide variety of academic missions, and the many outcomes associated with post-secondary, the question of “strategy” becomes quickly nuanced. We created this book to share thoughts from experts at the front lines of post-secondary education who are looking to what the future holds for our institutions, students, and communities. Strategies should not be built in vacuums. In this volume we aim to outline some considerations to be considered when building strategy in post-secondary. Our belief is that education is intended to provide a toolbox of knowledge, skills, abilities, and experiences. This toolbox must be both broad enough, and deep enough, to be foundational for future learning and applicable in a wide range of contexts. Employment and careers are obvious outcome goals that many think of with respect to post-secondary, and it should be clear that although important, they are not the only outcomes we should be concerned with. The chapters included in this volume will help to highlight considerations across a variety of contexts with the aim of continually developing an inclusive, enriched, deep, and sustainable post-secondary sector for the many positive outcomes associated with post-secondary.

The need for post-secondary to provide a strong and flexible foundation for the future has never been clearer. We are in a time of rapid local, global, and technological change, and the impacts on individuals and society are significant. By March of 2020, Covid-19 was declared a pandemic by the WHO, and post-secondary institutions, and many other sectors, worked rapidly to pivot online or close completely (see Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2023 for a timeline). Political unrest has been salient both locally and globally. For example, there have been concerns with risks of election fraud stemming from the 2016 Presidential election in the USA (Mueller, 2019), there was significant disruption in Ottawa due to the “Freedom Convoy/Convoi de la liberté” in 2022 (Public Safety Canada, 2022), and there are current, significant conflicts happening between Russia and Ukraine, and within Gaza. These are just some of the recent examples of social and political unrest. The skills and knowledge needed at a given moment can quickly change. A broad and deep toolbox allows individuals to effectively identify and use appropriate tools for the context.

In addition to social and political unrest, there have been rapid increases in technological capabilities. For those in post-secondary sectors, Generative AI is likely one of the most salient innovations to hit the sector since the widespread introduction of the internet. On November 30, 2022, ChatGPT was released by OpenAI (n.d.). ChatGPT is an example of Generative AI based in Large Language Models (LLMs), and at the time of this writing, is capable of providing rapid, relatively thorough responses to fairly detailed prompts, that are virtually undetectable as AI generated. On May 13, 2024, ChatGPT-4o was released by OpenAI, including increased abilities related to auditory and visual stimuli, in addition to text-based abilities. Of course, whether this information is accurate and ethical is an ongoing discussion. It is however, highlighting the need for critical consumers (and generators) of content. For example, OpenAI released an auditory chatbot that sounded remarkably like actress Scarlett Johansson after she declined willingness to have her voice used in this way (Murphy & McMahon, 2024). During the 2024 MetGala, Artificial Intelligence created a false image of Katy Perry attending the event in a gorgeous dress. It was so realistic that even Katy Perry’s mother believed it to be true (Kircher, 2024). On May 24, 2024, Google was widely criticized for a significant error in its artificial intelligence software called AI Overview which integrates with its search engine. AI Overview reported that former US President Obama is Muslim (he is not) (Field, 2024).

It is easy to villainize technology–many uses can be manipulative and promote falsehoods. But, technology can also be used for good. Highlighting the risks and benefits of artificial intelligence, in the below short videos created with the software HeyGen (https://www.heygen.com/), author Meghan demonstrates how “easy” it is to create videos in one language and have them presented as if speaking in another. Note that Meghan does not speak German, and even her German colleague was impressed with her apparent tone and delivery. To be totally clear: the video in German is not Meghan speaking. The software took her English video, manipulated her voice, language, and facial movements, to make it appear as her words were being spoken in German.

It is easy to see how much benefit can be gained for education through tools such as those that translate videos in authentic ways–suddenly language and intonation are no longer barriers. However, there is a need to be able to verify authenticity. For example, a manipulated video of a professor cancelling an exam could be quite problematic.

Issues related to authenticity open important and necessary conversations about instances of academic integrity in ways we have not yet had to consider. Academic integrity is often thought of as “not plagiarizing,” but actually encompasses a much broader array of professional behaviours in academia. Broadly, academic integrity rests on 6 values that should be practiced and upheld within academic contexts: honesty, trust, fairness, respect, responsibility, and courage (International Centre for Academic Integrity, 2021). Misrepresenting thoughts, ideas, and individuals clearly undermines values such as honesty, trust, and responsibility. Importantly, not acting when we know this is happening is a failure to show responsibility and courage. An ongoing frontier is how to act when such actions occur. There is a dearth of regulation, especially surrounding technology, and there are grey zones: banning technology is clearly not the answer as it can provide great benefits. Any fulsome strategy in post-secondary must include considerations of integrity.

It must be said that campuses are composed of people. Students, and their learning, are paramount when considering strategy. Their development, wellness, success, and learning are overlapping, but distinct, concepts, each requiring care-filled strategy. Yet students are also not the only people on campus. Campuses are rich communities with full- and part-time staff, volunteers, full- and part-time professors on a variety of career tracks, administrators, and additional invested parties. Their development, wellness, and learning are also vital when considering strategy. At the big picture level, campuses are embedded within broader communities, neighbourhoods, cities, and beyond. The opportunities for positive, ongoing, enriching relationships between campuses and communities are vast, benefiting all involved. Post-secondary education and institutions need not, and should not, be an ivory tower. Comprehensive post-secondary strategy should include considerations of the environments in which campus community members live and work, their wellness, and considerations related to the broader communities in which campuses exist.

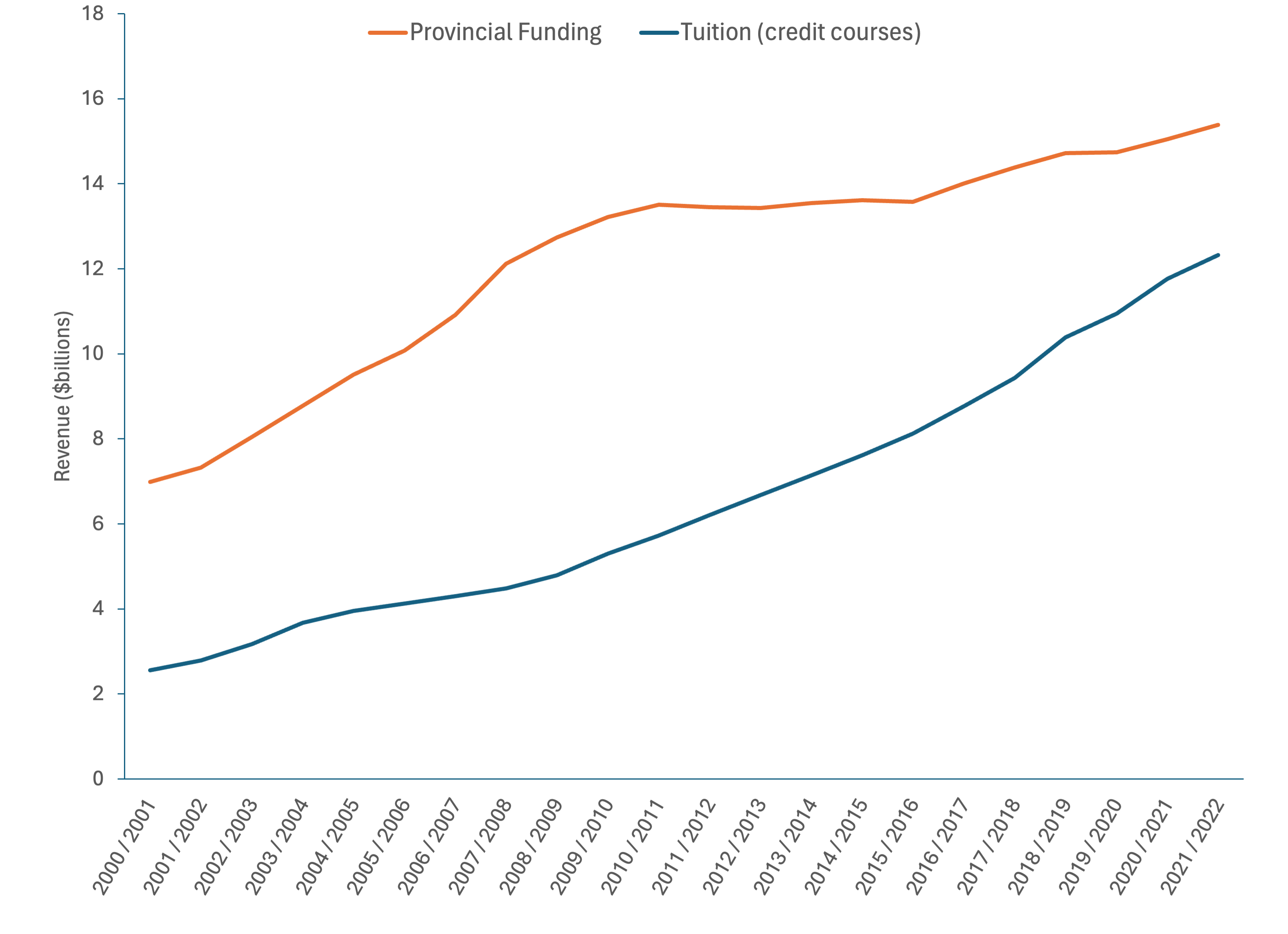

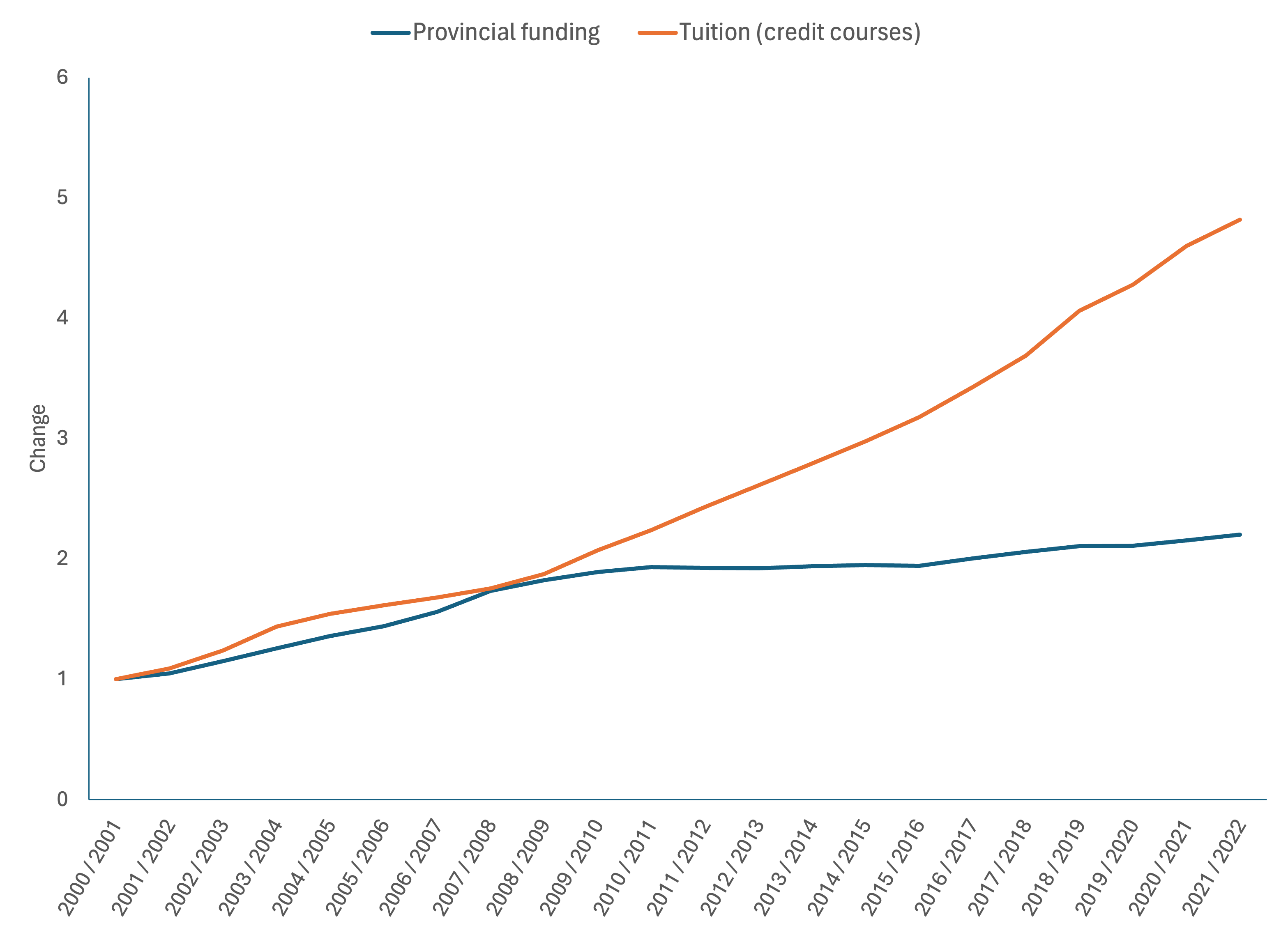

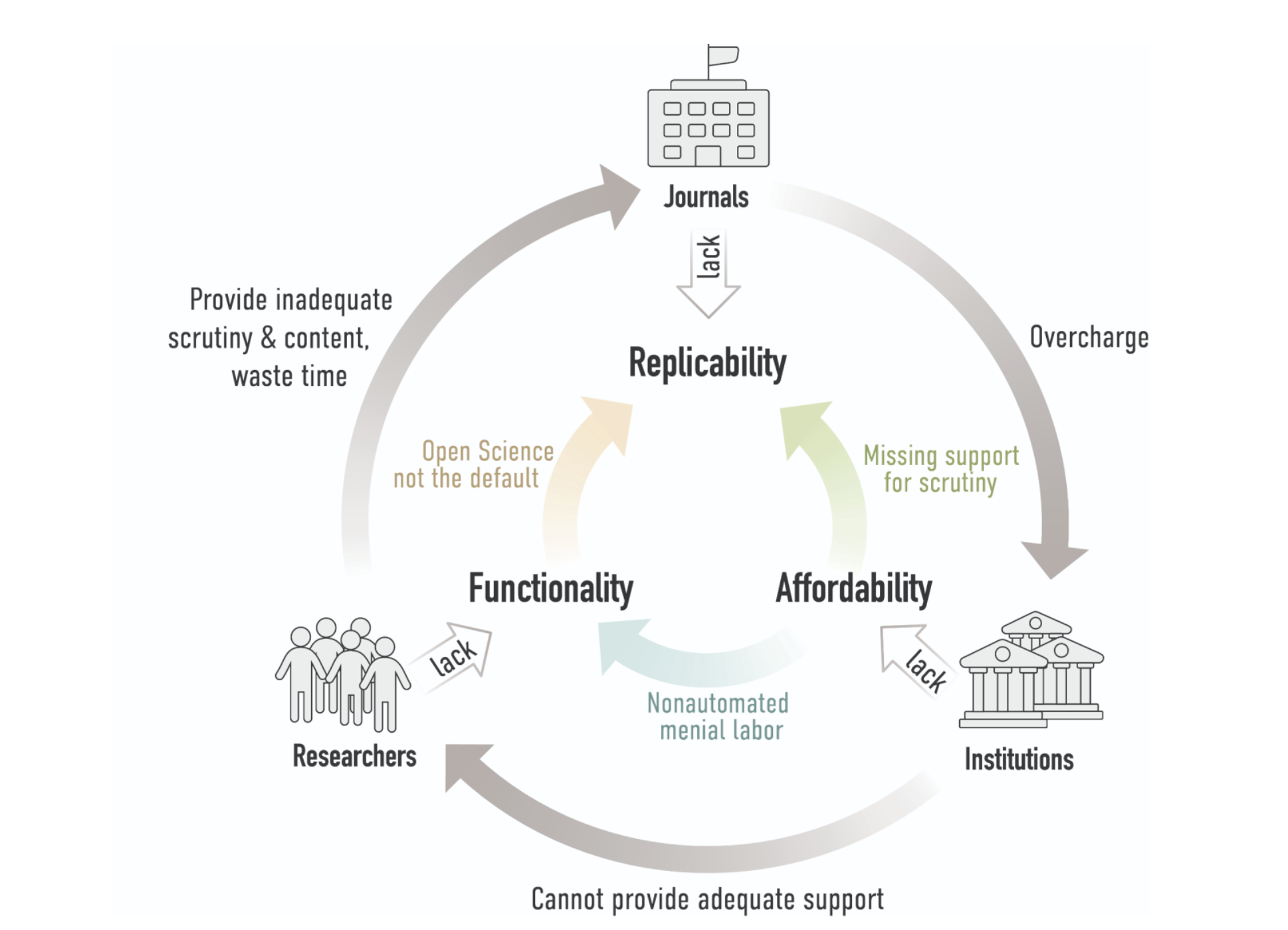

Leaning into an often-challenging part of strategy, and the implementation of strategy, is the consideration of finances. Healthy, supportive, innovative environments require funds. Published in 2023, the most recent Report of the Advisory Panel on the Federal Research Support System (“The Bouchard Report”), highlights significant concerns with financial support for our research infrastructure. It shares that although Canada is excellent in the research space, funding is not sufficient to sustain this excellence. The report calls for strategic vision, and a strategic advisory body.

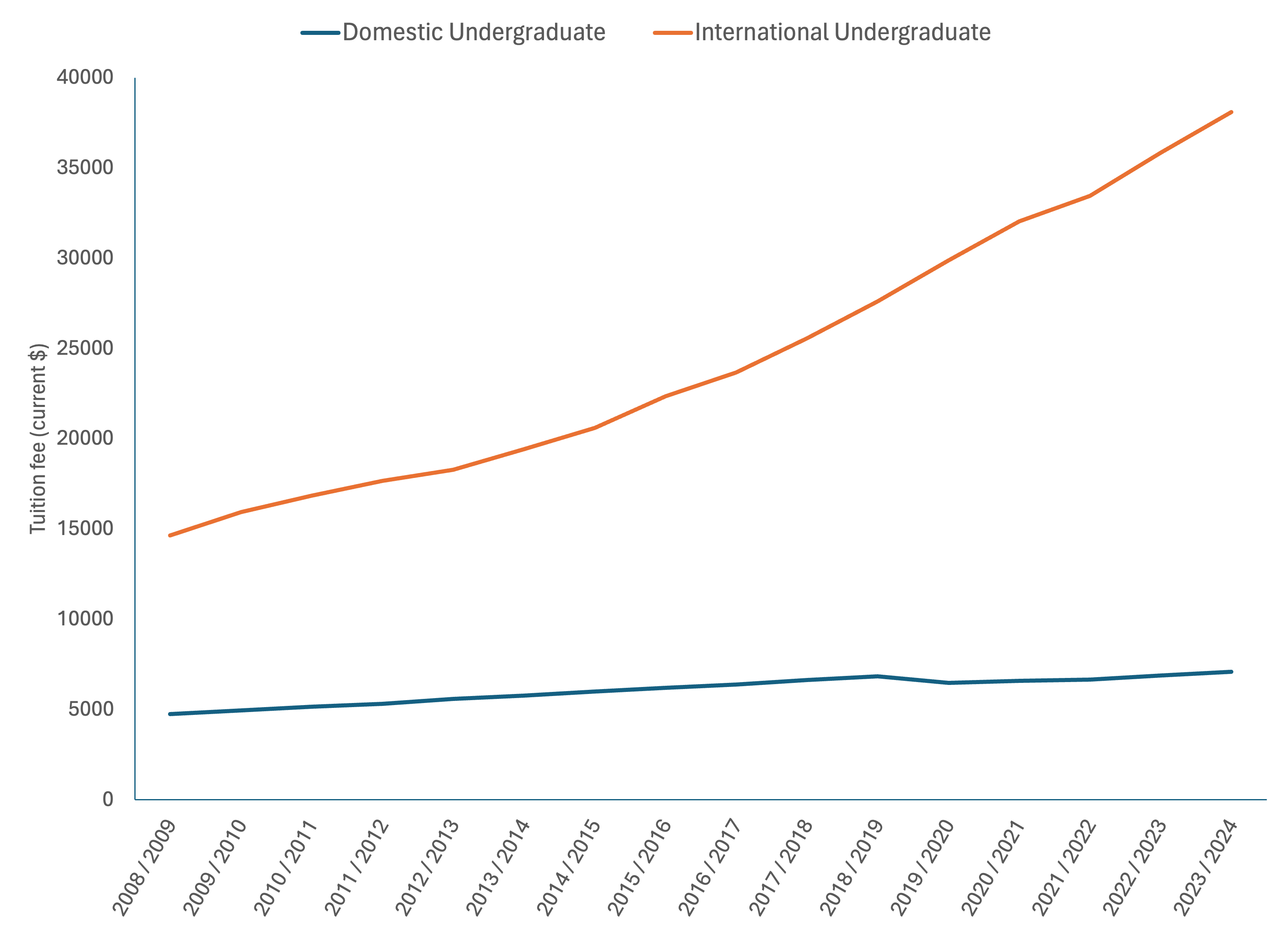

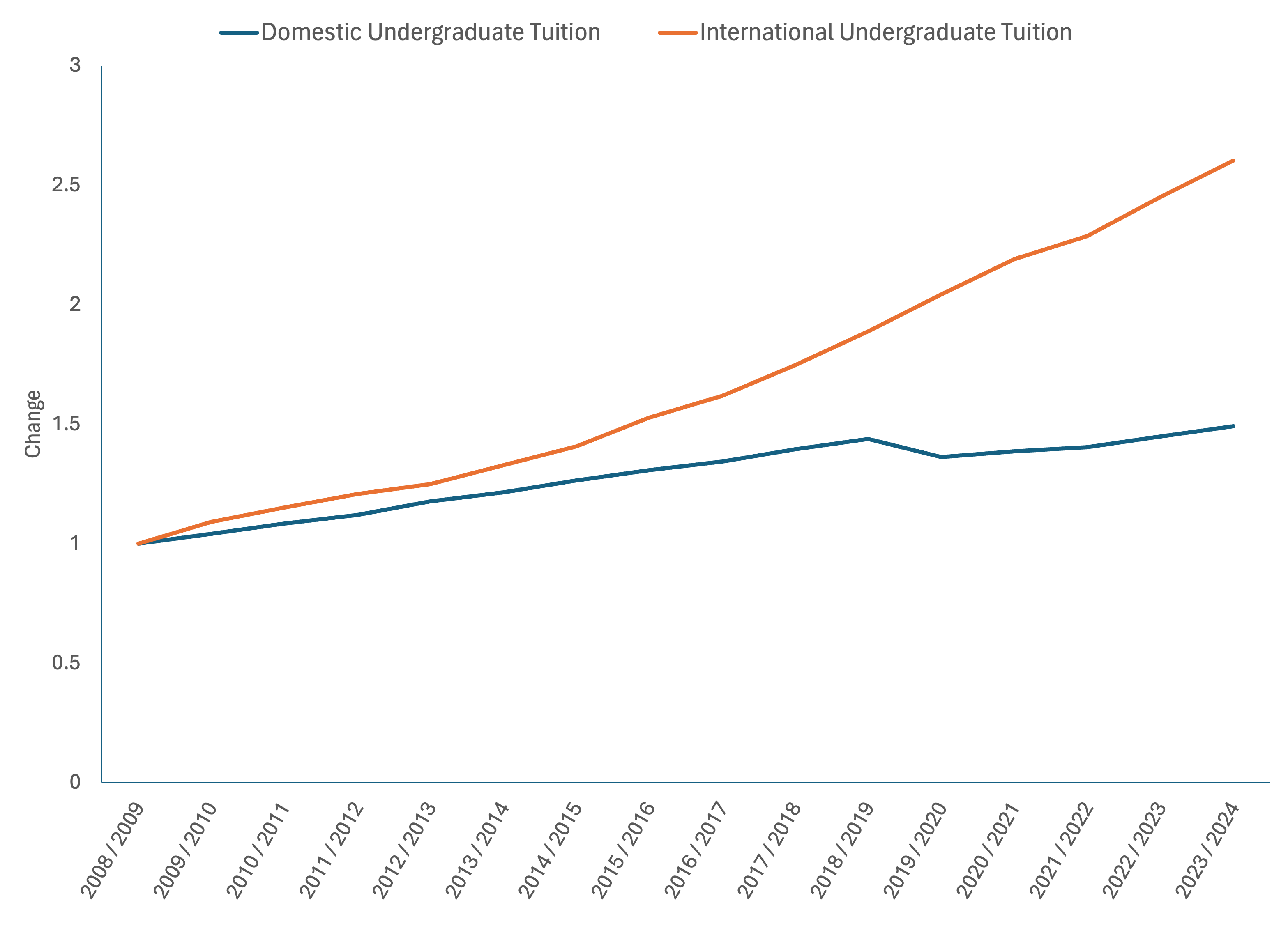

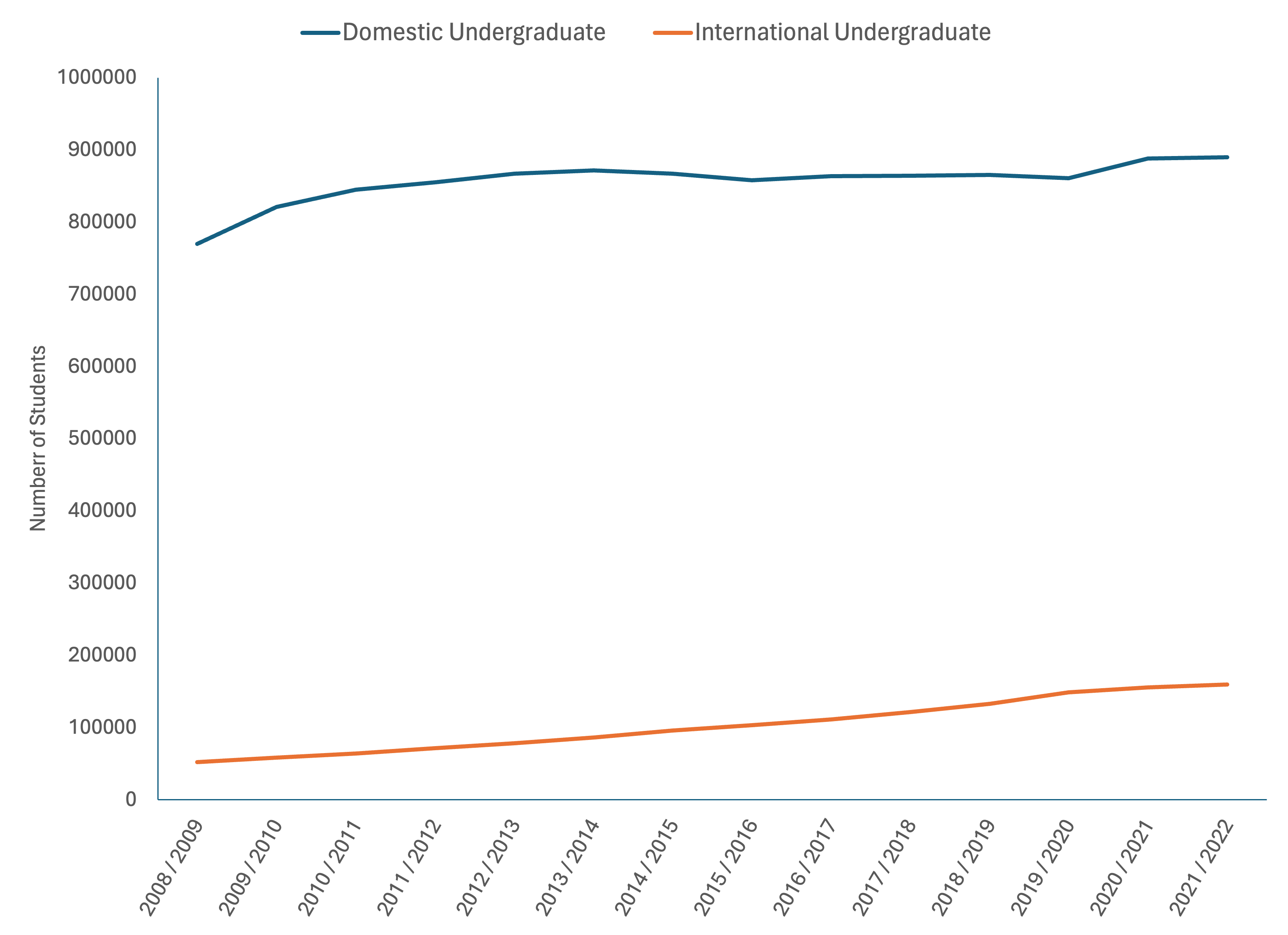

Concerns with funding are not limited to research. In 2023, the Government of Ontario launched a blue-ribbon panel to explore how to ensure sustainability for post-secondary institutions within Ontario while maintaining student experience (Harrison, 2023). It called for increased financial support from the province, in collaboration with higher tuition. It also called for increased financial literacy of campus communities (specifically for board members, though presumably we all could use some brushing up in this area), and highlighted financial risks associated with dependence on international students. Importantly, the panel also highlighted that financial sustainability is not one-size-fits-all: different contexts require different solutions. Many other provinces are conducting similar reviews.

To the relief of many, the Federal budget released by the Canadian government in 2024 showed important support for post-secondary education and institutions (Government of Canada, 2024). For example, GST requirements were relaxed to incentivize building of new residences, amendments were included to the Canadian Education Savings Act to support saving for post-secondary, student grants were increased, and importantly, increases for research support were included. That said, although funds for post-secondary, including graduate student support, have been promised by the government (e.g., Government of Canada, 2024), consultants in the field are raising flags that while the dollar amounts sound big, we are not where we should be in terms of funding, and some of the promised funding may not be guaranteed (e.g., Higher Education Strategy Associates, 2024).

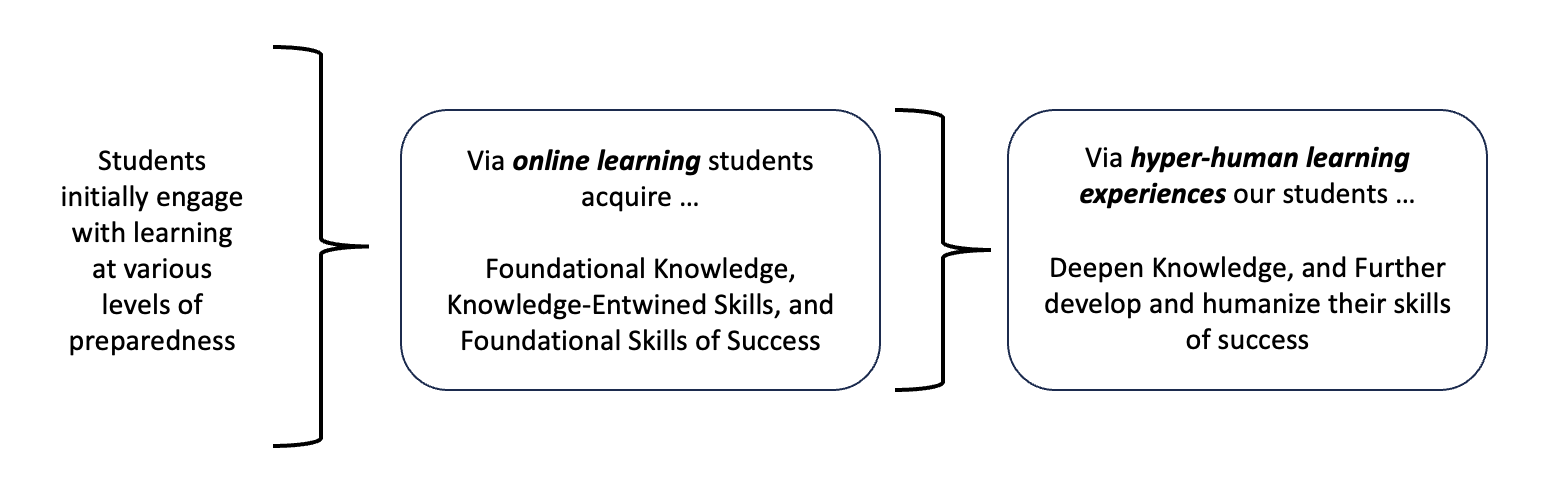

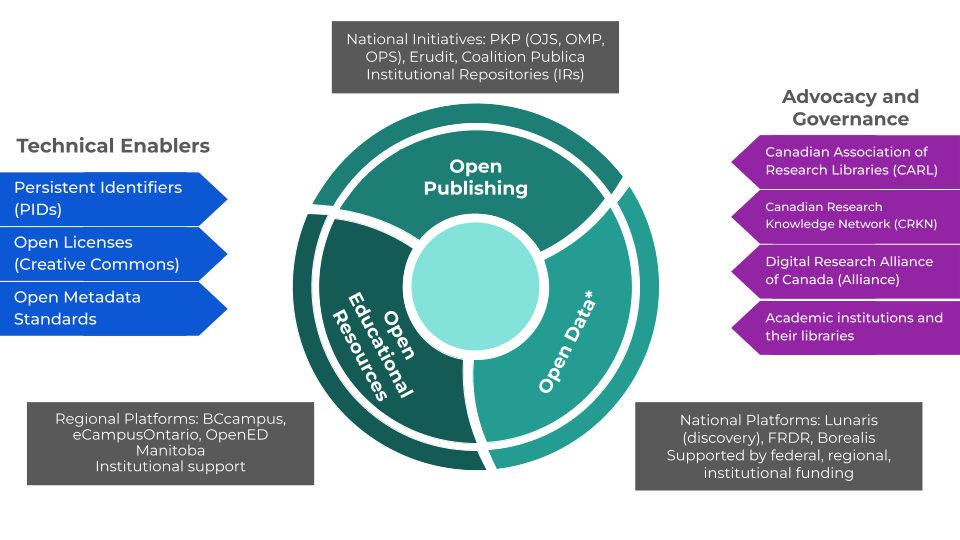

So, where does this book fit in? We opened with a focus on needing strategy. Our intention is not to propose a strategy. Indeed, we think that would be unwise. As we noted, strategies must meet the needs of specific cases, and thus will vary. In this book, we hope to share some insights about tactics that should be considered for strategy. We intentionally start this book with chapters focused on inclusion, including chapters on Equity, Diversity, and Accessibility in Post-Secondary Education, Ways of Knowing and Higher Education, Indigenization and the Future of Post-Secondary Education, and Accessibility in Higher Education. We then transition into chapters focusing on supporting the people in our campus communities, with chapters including The Developmental Perspective on Youth in Post-Secondary Education, Promoting Post-Secondary Student Well-Being, Campus Mental Health: A Whole Community Responsibility, and Transforming Higher Education: A Case for Transformational Leadership. We then move to physical and financial considerations with chapters in The Role of the Physical Campus for Productivity and Health, and Financing Canadian Colleges and Universities in the 21st Century. Next we turn to academic issues with chapters including The Essentiality of Academic Integrity in an Increasingly Disrupted and Polarized World, Re-Imagining Education for an Uncertain Future: Can Technology Help Us Become More Human?, What are Large Language Models Made of?, and Beyond the Paywall: Advocacy, Infrastructure, and the Future of Open Access in Canada. We conclude this volume by highlighting the importance of community in our campuses with chapters on Envisioning Public Policy and Practices for Experiential Learning in Post-Secondary Education, and Building Better Health Sciences Education.

Importantly, this book is not the end, but a start. We look forward to future editions that include additional necessary topics when building strategy related to post-secondary. For example, chapters on specifics related to the science and practice of learning and teaching, the importance of interdisciplinary work, the “why” of grading and assessment methods, governance structures, life and career development, upskilling, transfer credit mobility, research funding, and more.

As we close, we want to highlight some features of this book. Chapters each have their own URLs. This means that you can easily share individual chapters by way of URL as you wish, in addition to sharing the main link for the book. This book is open access, with most chapters being protected either under CC-BY 4.0 or CC-BY-NC 4.0 licenses. This means you are encouraged to share broadly (please see specific licensing associated with each chapter), and there are no costs to using this book. Content has been generously shared by authors, who retain copyright of their chapters, with the intention of removing barriers to accessing content. We ask that you cite chapters in future work so authors can receive academic credit for their work. To help with this, recommended citations are included at the bottom of each chapter. To learn more about creative commons licensing permissions, we recommend visiting https://creativecommons.org/share-your-work/cclicenses/ (Creative Commons, n.d.).

We want to share a heartfelt thanks at this point. This book was created incredibly quickly thanks to funding received from the Queen’s University Library team in their support of open educational resources. No authors were paid for their chapters in this book. That this book came together so quickly, with such incredible topics covered, is truly a testament to the academic network in Canada. Many authors in this book received “cold emails” asking whether they would be willing to share their knowledge, and we were humbled that they, and closer colleagues, agreed to participate. Writing a chapter is harder and more time consuming than it sounds–to our dear authors, thank you. We hope you are proud of this resource, and the conversations we hope it will facilitate.

This project could not have come to fruition without our student project coordinators. Sophia Coppolino and Floor (Flo) Nusselder were essential team members and were truly the glue that helped keep pieces (and email chains) together. The skill and professionalism that these two soon-to-be-graduates demonstrated in a large-and-fast project is testament to the incredible folks we have coming through our post-secondary systems. As you both graduate, please know that you have a community cheering you on. Teamwork really does make the dream work–thank you for being a part of it!

References

Baum, S., Ma, J., & Payea, K. (2005). Education pays, 2004: The benefits of higher education for individuals and society revised edition. College Board Advocacy & Policy Center. https://research.collegeboard.org/media/pdf/education-pays-2004-full-report.pdf

Bushnik, T., Tjepkema, M., & Martel, L. (2020). Socioeconomic disparities in life and health expectancy among the household population in Canada. Statistics Canada. https://www.doi.org/10.25318/82-003-x202000100001-eng.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023). CDC museum COVID-19 timeline. https://www.cdc.gov/museum/timeline/covid19.html

Creative Commons. (n.d.). About CC Licenses. https://creativecommons.org/share-your-work/cclicenses/

DeClou, L. (2014). Social returns: Assessing the benefits of higher education (Report No. 18). Toronto: Higher Education Quality Council of Ontario. https://heqco.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/@Issue-Social-Returns.pdf

Field, H. (2024, May 24). Google criticized as AI Overview makes obvious errors, such as saying former President Obama is Muslim. CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com/2024/05/24/google-criticized-as-ai-overview-makes-errors-like-saying-president-obama-is-muslim.html

Government of Canada. (2024). Budget 2024: Fairness for every generation. https://budget.canada.ca/2024/report-rapport/budget-2024.pdf

Harrison, A. (2023). Ensuring financial sustainability for Ontario’s postsecondary sector. Blue-Ribbon Panel on Postsecondary Education Financial Sustainability. https://files.ontario.ca/mcu-ensuring-financial-sustainability-for-ontarios-postsecondary-sector-en-2023-11-14.pdf

HeyGen. (n.d.). [Video translation software]. https://www.heygen.com/

Higher Education Strategy Associates. (2024). The 2024 federal budget: A Higher Education Strategy Associates commentary. https://higheredstrategy.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/2024-04-16-Budget-Commentary-v2.pdf

Industry Canada. (2001). Achieving excellence: investing in people, knowledge and opportunity: executive summary. Government of Canada, Ottawa, ON. https://publications.gc.ca/collections/Collection/C2-596-2001-1E.pdf

Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada (2023). Report of the Advisory Panel on the Federal Research Support System. https://ised-isde.canada.ca/site/panel-federal-research-support/sites/default/files/attachments/2023/Advisory-Panel-Research-2023.pdf

International Center for Academic Integrity. (2021). The fundamental values of academic integrity (3rd ed.). https://academicintegrity.org/images/pdfs/20019_ICAI-Fundamental-Values_R12.pdf

Kircher, M. M. (2024, May 7). Don’t be fooled by A.I. Katy Perry didn’t attend the Met. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/05/07/style/katy-perry-met-gala-ai.html

Lederman, D. (2024, January 23). Higher ed workforce rebounding from pandemic. Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/news/workplace/2024/01/23/higher-ed-workforce-recovering-slowly-pandemic

Muller, R. (2019). Report on the investigation into Russian interference in the 2016 presidential election. US Department of Justice. Washington, DC, USA. https://www.justice.gov/storage/report_volume2.pdf

Murphy, M., & McMahon, L. (2024, May 21). Scarlett Johansson ‘shocked’ by AI chatbot imitation. British Broadcasting Corporation. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cm559l5g529o

National Center for Education Statistics. (2023). Employment and unemployment rates by educational attainment. U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator/cbc

OpenAI. (n.d.). ChatGPT [Large language model]. https://chatgpt.com/

OpenAI. (2024). Hello GPT-4o. https://openai.com/index/hello-gpt-4o/

Public Safety Canada. (2022). Parliamentary committee notes: Evolution of the Freedom 2022 Convoy. https://www.publicsafety.gc.ca/cnt/trnsprnc/brfng-mtrls/prlmntry-bndrs/20221013/04-en.aspx

Statistics Canada. (2019). Postsecondary graduates in Canada: Class of 2015. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/11-627-m/11-627-m2019074-eng.htm

Statistics Canada. (2020). Half of recent postsecondary graduates had student debt prior to the pandemic. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/200825/dq200825b-eng.htm

Statistics Canada. (2021a). Tuition fees for degree programs. https://www.statcan.gc.ca/o1/en/plus/176-weighing-costs-and-benefits-university-education

Statistics Canada. (2021b). Weighing the costs and benefits of a university education. https://www.statcan.gc.ca/o1/en/plus/176-weighing-costs-and-benefits-university-education

Statistics Canada. (2024). Table 37-10-0156-01 Characteristics and median employment income of postsecondary graduates five years after graduation, by educational qualification and field of study (STEM and BHASE (non-STEM) groupings) [Data table]. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=3710015601

Universities Canada. (2024). Facts and figures. https://univcan.ca/universities/facts-and-stats/

Uppal, S., & LaRochelle-Côté, S. (2016). Understanding the increase in voting rates between the 2011 and 2015 federal elections. Statistics Canada. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/75-006-x/2016001/article/14669-eng.htm

How to Cite

Norris, M. E., & Smith, S. M. (2024). Applying tactics to develop strategy: Envisioning the future of higher education. In M. E. Norris and S. M. Smith (Eds.), Leading the Way: Envisioning the Future of Higher Education. Kingston, ON: Queen’s University, eCampus Ontario. Licensed under CC BY 4.0. Retrieved from https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/futureofhighereducation/chapter/tacticsforstrategy/

About the authors

Meghan E. Norris

Meghan Norris, PhD, currently serves as the Undergraduate Chair in Psychology at Queen’s University. Her current areas of interest focus on systems within higher education, and the science and practice of teaching and learning.

Steven Smith

Applying Tactics to Develop Strategy: Envisioning the Future of Higher Education Copyright © 2024 by Meghan E. Norris and Steven M. Smith is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

The Future of Equity, Diversity, Inclusion, and Accessibility in Post-Secondary Education

The Future of Equity, Diversity, Inclusion, and Accessibility in Post-Secondary Education

Katelynn Carter-Rogers1,2, Steven M. Smith2, Chiedza Chigumba2, and Vurain Tabvuma2

1St. Francis Xavier University

2Saint Mary’s University

Introduction

In this chapter we will discuss some of the many ways in which equity, diversity, inclusion, and accessibility (EDIA) are being considered in post-secondary education, and how the role of EDIA is likely to evolve over the coming years. We will start with an examination of the shift in the nature of the people at academic institutions over time, both in terms of students, and the faculty teaching them. Next, we will discuss what we mean by EDIA, how the definitions of EDIA have changed over time in general within the literature, and how post-secondary education (PSE) is leading the way in many instances. We will address the role and need for inclusive practices in post-secondary education and the benefits of EDIA for students, faculty, and institutions. Finally, we will take an educated guess at what the future of EDIA in PSE will bring, and how institutions can prepare for, facilitate, and manage those changes.

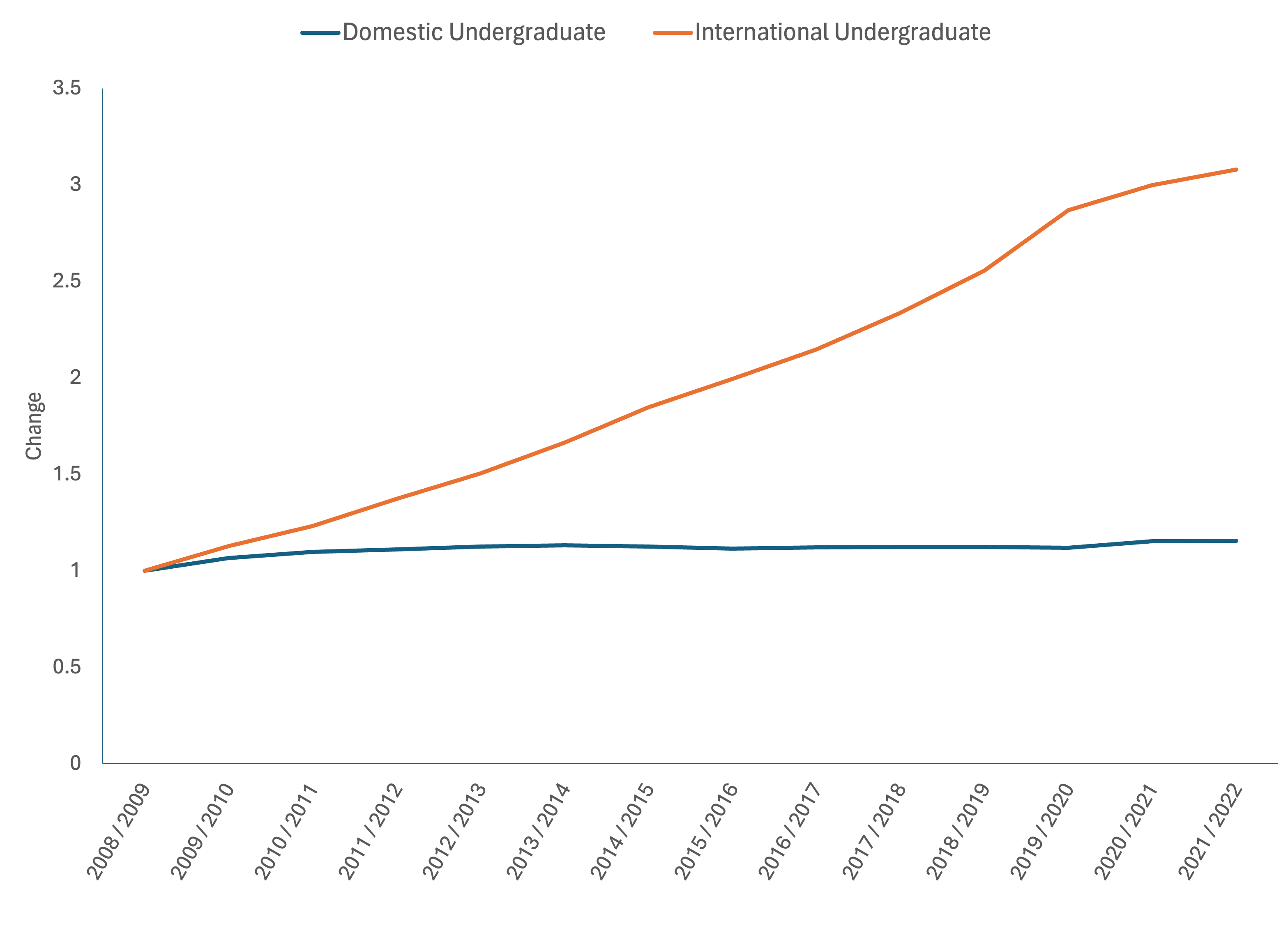

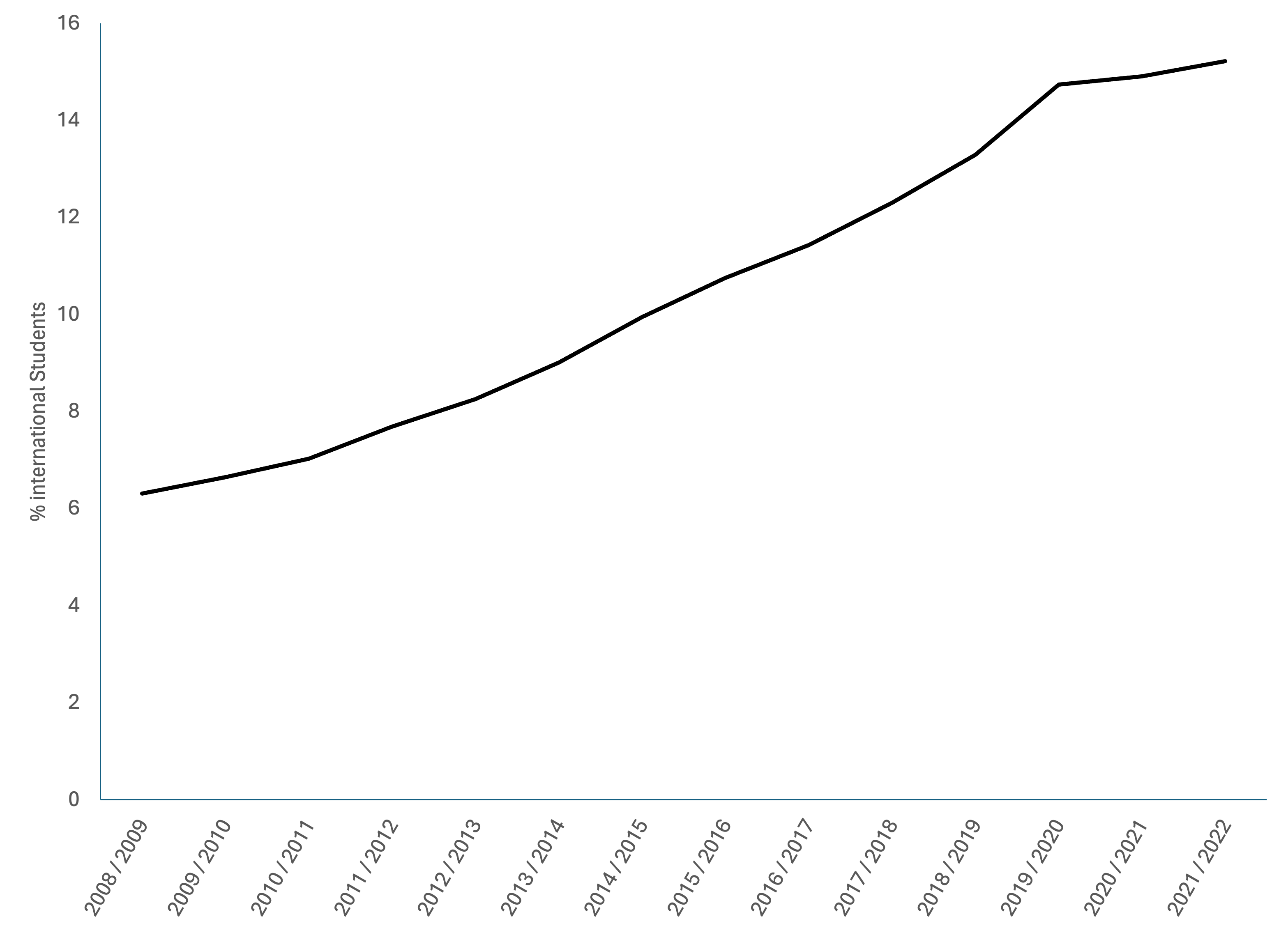

Student Demographics Over Time

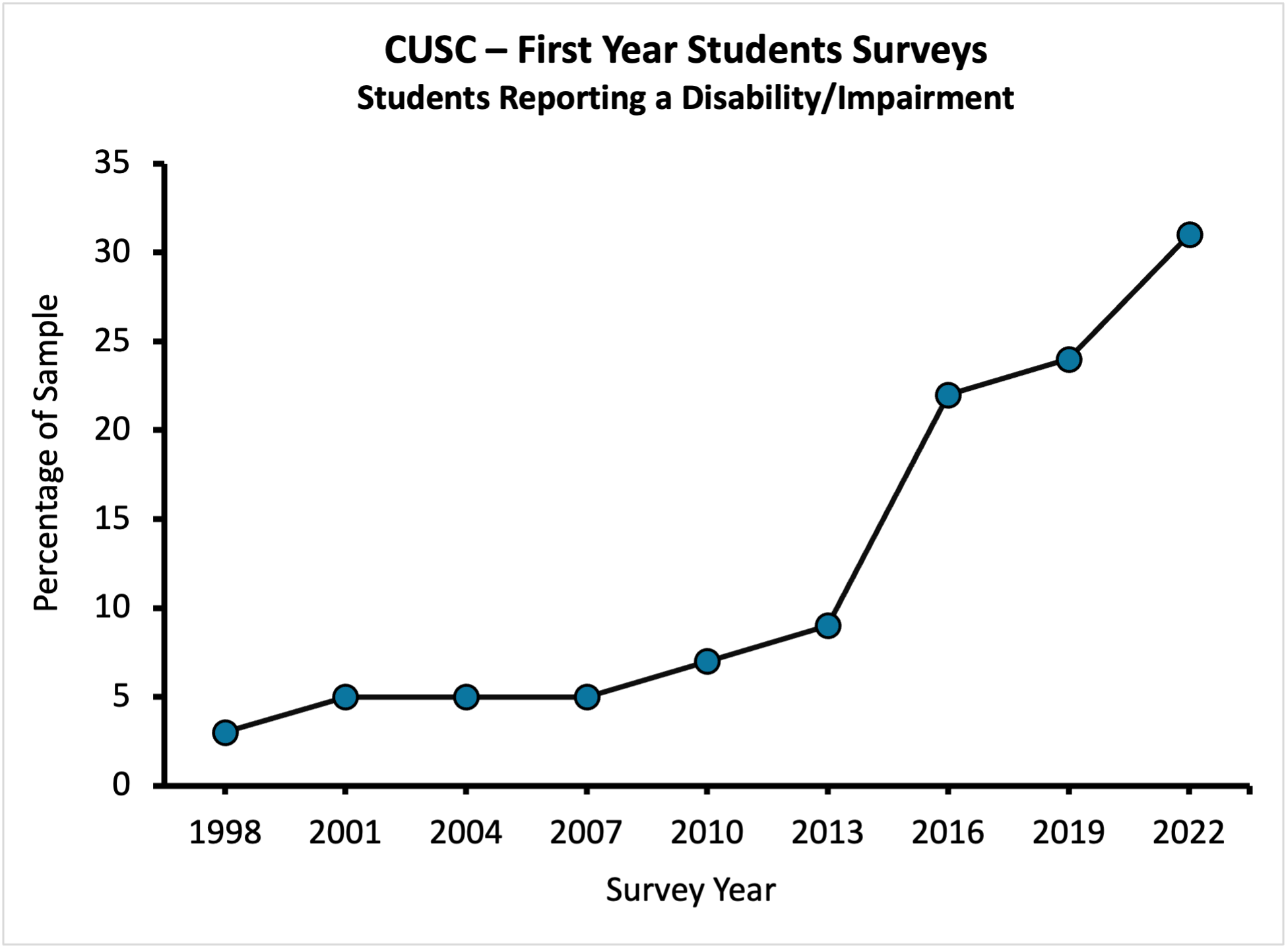

There are now over 2.2 million students at colleges and universities in Canada, and that is more than double the number that attended in 1980 (Statistics Canada, 2023). Despite a push to increase access to PSE for Indigenous students in Canada, Indigenous youth were half as likely (37%) to have taken some form of post-secondary education as non-Indigenous youth (72%) (Layton, 2023). Interestingly, although there is already significant diversity in Canadian undergraduates, we see that some groups are over-represented compared to the general Canadian population (e.g., South Asian, Chinese, Korean) some are essentially at par with population (e.g., Arab, Southeast Asian, Japanese) and some are lower than would be expected by population (Latin American, Black, Filipino); overall, some 30% of PSE students identify as a visible minority (Brunet & Galarneau, 2022). Over 400,000 of the students (or 18%) are international, which is 10 times the number of international students since 1980 (Statistics Canada, 2023). Students with disabilities also face challenges, with only 42% achieving some level of PSE (Furrie, 2017).

How is EDIA operationalized?

Seeing how the university population has changed and become more diverse over the last several decades, it has become apparent that resources and course content is not as relevant or relatable to everyone who is within the learning environment, there may also be cases where the content is not applicable, or generalizable for all populations equally. How do we ensure that everyone who is experiencing our learning environment fundamentally feels like they belong within this space and that it is relevant to them? That is what the intention of implementing EDIA within organizations and institutions is meant to do. There has been an evolution of EDIA, drastic changes to the way it is talked about (transitioning from EDI to EDIA, and other abbreviations) (see Table 1), and also changes within the literature describing what the best way to work with diverse people.

Table 1

Common Abbreviations used within the Equity, Diversity, Inclusion, and Accessibility space

| Common Abbreviations | |

| EDI | Equity, Diversity, & Inclusion |

| EDIA | Equity, Diversity, Inclusion, & Accessibility |

| EDIRA | Equity, Diversity, Inclusion, Reconciliation, & Accessibility |

| EDII-A | Equity, Diversity, Inclusion, Indigeneity, & Accessibility |

| D&I | Diversity & Inclusion |

| DEI | Diversity, Equity, & Inclusion |

| IDEA | Inclusion, Diversity, Equity, & Accessibility |

| DEIB | Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, & Belonging |

| JEDI | Justice, Equity, Diversity, & Inclusion |

| JEDDI | Justice, Equity, Diversity, Decolonization, & Inclusion |

Prior to the 1980’s, organizations focused on equality, and equal opportunity for the groups that were legally protected from discrimination, which focused more broadly on race and sex (Kelly & Dobbin, 1998). Historically, shifts towards equity have come with climates that have necessitated uncomfortable conversations. When diversity became the focus, this brings attention to the importance of how it can benefit the organization overall (Trawalter et al., 2016). Progress in achieving diversity goals has come because of social movements driving change and causing society to recognize the lived experiences of racialized groups (Ray & Melaku, 2023). If left to voluntary targets, EDIA progress would be slow (Cukier, 2023) and inequalities would persist. Over the years, we have seen significant changes to how diversity is considered, including gender identity, ability, personality characteristics, religion, and ethnicity, just to name a few (Kirby et al., 2023; Pascual et al., 2023; Unzueta & Binning, 2012).

There has also been discourse in the inclusion literature (Shore et al., 2011), calling for a shift from measuring diversity to actively considering how to create an inclusive space for everyone (Ferdman, 2014; Mor Barak, 2022; Nishii & Rich, 2013; see also Tabvuma et al., 2023). However, a focus on making the majority feel comfortable risks experiencing a repeat of history when calls for EDIA were widely devalued and labelled as ineffective (e.g., Chambers et al., 2023; Chilton et al., 2022; Winnick, 2010). It is important for all sides to be heard; inclusion is not about the majority deriding the realties that equity seeking groups face. It is just as important to have conversations about uncomfortable topics with a goal to foster a sense of belonging and not silence the voices of those whose lived experiences are negatively impacted by policies aimed at maintaining the status quo. Myth busting is one way to steer perceptions away from misconceptions and towards common understanding of the EDIA issues in PSE (Chambers et al., 2023).

These issues show the importance for considering more than just recruitment initiatives when seeking to promote inclusion. Research by Gebert et al. (2017) highlights that during transitions, insufficient tolerance for diverse populations among leadership can create discomfort and unwelcoming atmospheres and lower retention. Despite extensive discourse on EDIA, numerous organizations still lack diversity, particularly within their leadership ranks (Statistics Canada, 2021a; 2021b). Despite decades of trying to enhance diversity, significant wage gaps and underrepresentation persist within organizations, signaling systemic barriers to acceptance, cultural transformation, and sustained diversity. With the backlash against race-based admission approaches linked to affirmative action, PSE institutions in the USA are now expected to seek diversity in their admissions process through factors other than race (Savage, 2023). It remains to be seen how much of an impact this will have on the visible diversity of students in PSE and the workforce. Backlash and myths are effective tools in silencing the voices of those who would otherwise advocate against self-segregation in favor of inclusive approaches that foster a sense of belonging; over time, they can breed assimilation as people conform (Shore et al., 2011) to be accepted as insiders for personal and professional. Recognizing these challenges, scholars have begun advocating for a paradigm shift from merely studying diversity to focusing on inclusion (Carter-Rogers et al., 2022a; Ferdman, 2014; Mor Barak, 2022; Nishii & Rich, 2013; Shore et al., 2011; Smith, et al., 2022).

Issues such as unwelcoming environments and underrepresentation at least partly stem from leadership using these terms interchangeably, and thus missing important considerations when it comes to facilitating inclusion. When “diversity” is discussed, most are referring to the people’s “affinity” that makes them different or unique within a space (Star, 2022). This is problematic because these diverse traits become a metric that is measured as an outcome of success, instead of adjusting or making change within an environment. These affinities are also typically assessed visibly, which then negates hidden or invisible diversity. The Canadian Commission for United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) has done a great job explaining and defining EDIA as it impacts the Canadian education system and showing that each dimension needs to be considered differently (see Table 1).

Table 2

Inclusion, Diversity, Equity & Accessibility (IDEA) Good Practices toolkit (Baker & Vasseur, 2021).

Inclusion | Equity |

Inclusion is ensuring all individuals are equally supported, valued, and respected. This is best achieved by creating an environment in which all individuals (students, faculty, staff, and visitors) feel welcomed, safe, respected, valued, and are supported to enable full participation and contribution.

| Equity is the fair treatment and access to equal opportunity (justice) that allows the unlocking of one’s potential, leading to the further advancement of all peoples. The equity pursuit is about the identification and removal of barriers to ensure the full participation of all people and groups.

|

Diversity | Accessibility |

Diversity is the wide range of attributes within a person, group or community which makes them distinctive. Dimensions of diversity consider that everyone is unique and recognizes individual differences including ethnic origins, gender (identity, expression), sexual orientation, background (socio-economic status, immigration status or class), religion or belief, civil or marital status, family obligations (i.e., pregnancy), age, and disability.

| Accessibility is the provision of flexibility to accommodate needs and preferences, and refers to the design of products, devices, services, or environments for people who experience disabilities. It can also be understood as “a set of solutions that empower the greatest number of people to participate in the activities in question in the most effective ways possible.”

|

What is not discussed within Table 2 but is starting to surface within the EDIA literature, is the idea around belonging, or belongingness (Kirby & Zhang, 2024). Although Shore et al. (2018) begins to speak on the sense of belonging in the context of inclusion, and the uniqueness that one feels within their environment leading to them ultimately being retained, the concept from an EDIA perspective is still new in the organizational context. Belonging is where the PSE literature is more informed on implementing change within the academic space.

Value of EDIA in Post Secondary Education

In 1998 the U.S. Court of Appeals ruling in Wessmann v Gittens (1998) struck down the school’s race-based admissions quota that reserved half the seats for students from diverse racial backgrounds; in the 1997-98 school year this half was comprised of 18 White, 13 Black, 9 Asian-American and 5 Hispanic students (Wessmann v. Gittens, 1998). Similarly, in the Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. President and Fellows of Harvard College (2023) race-based considerations were ruled unconstitutional by the Supreme Court. The key takeaway highlighted from media articles was the need to prove the value of diversity (Axtman, 1998; Lewin, 1998; Liptak, 2023). At the PSE level, the value of EDIA comes through when tertiary education aids in developing individuals who can work in teams with, or manage people from, diverse backgrounds. Diversity in higher education fosters interactions that bring value to the development of strategy through diverse thought. Furthermore, diversity creates room for the generation of innovative ideas (Díaz-García et al., 2013) by bringing together minds, perspectives and experiences from different backgrounds and identities.

At PSE institutions, the diverse student population brings together diversity in thought and experience at an advanced level of maturity compared to high school. Students who come from different backgrounds often come with diverse ways of learning and differing notions of what is expected of them both in the classroom and in their academic work (Nelson, 1996). What is often presumed to be lack of motivation, means or ability can also be a function of differences in how students learn, including attitudes towards peer-learning, or differences in how the standard of their high school education prepared them for college (Nelson, 1996; Treisman, 1992). Often students from different backgrounds, with different levels of college preparation, are expected to know and understand the expectations of their professors (Nelson, 1996), and supporting student diversity involves providing opportunities and resources for equitable learning. This may include taking time to set expectations and ensuring understanding using exercises that are reviewed collectively (Nelson, 1996). Creating opportunities for regular peer-learning has been found to be beneficial for students who come from backgrounds that discourage such a strategy as it may be misunderstood as cheating, or from social environments where such a strategy may risk students facing bullying for appearing as being nerdy (Nelson, 1996). Notably peer learning through study groups is a strategy that other successful student groups regularly make use of, such as Asians and those from social environments where peer learning was encouraged, (Nelson, 1996).

EDIA and Sense of Belonging in PSE

When creating pipelines within the education system so that more diverse students can access PSE and subsequently enter the workforce, we must consider their integration into this space (Tienda, 2013). Students who are experiencing more educational barriers (i.e., first generation students, Black and Indigenous students, students living with disabilities, working students, etc.) experience the most uncertainty in their sense of belonging within PSE, leading to feelings of isolation (Brooms, 2020; DeRossett et al., 2021; Fong et al., 2021). We see that the students’ sense of belonging has a significant impact on whether they are successful in their integration.

Students with increased connection to the environment have increased sense of belonging (Astin, 1994; 2007; Malone et al., 2012; Schachner et al., 2019; Slaten et al., 2018; Tinto, 1993; 2010). Astin’s (1994) Inputs-Environment-Output (I-E-O) model allows for consideration of students’ demographic backgrounds when implementing and assessing the outcomes for successful transition into PSE. These approaches are essential to academic success; the integration into campus life is just as important as obtaining high grades (Astin, 1994; 2007). A student’s failure to integrate into the campus culture, both socially and intellectually, is a factor in why students struggle and/or fail in PSE (Tinto, 1993; 2010). Carter-Rogers, et al. (2022b) found that there were clear educational barriers being experienced by the diverse student population ranging from financial hardships, housing insecurity, lack of social support, generational trauma, family substance abuse, and negative relationship dynamics. These barriers, though out of the control of the institution, put into perspective the importance of sense of belonging, and continued social support systems needed within the PSE environment. Resources on campus must exist so that students who are from more diverse backgrounds can find a sense of belonging within the educational space, ensuring they can stay and feel safe within the academic environment.

Programming to Facilitate Belonging for Students

Student transitions are hard, and in most cases, it is not the challenge of doing well in class, it is the adjustment to the academic culture that is most impactful. Geography, gender, ethnic background, and socioeconomics all influence this outcome. In PSE institutions, graduation rates vary dramatically from close to 90% to well under 50% — and that is just from those who are reporting statistics (see MacLean’s, 2018).

Most colleges and universities in North America have specific programs put in place to help students transition from high school (or other institutions) to their programs. Indeed, there are multiple national (e.g., the Annual Conference on First Year Experience; the National Student Success Conference) and regional (e.g., the Atlantic Association of College and University Student Services; the California Strengthening Student Success Conference) conferences and organisations that specifically aim to support student transition and success. At each of these conferences (as illustrated in their associated journals and newsletters) there are countless programs being run every year, all with the goal of easing the transition of students from where they were, to where they are at. In a recent survey of Canadian first year experience and students in transition programming being offered at Canadian colleges and universities, every institution responding offered more than one program for students to support their acclimation to academia and the institution (see Smith, et al., in press).

First-year experience and students in transition programs take a wide variety of forms, including first year seminars to support student academic and writing skills, programs integrated with required academic courses, programs for transfer students, programs for international students, mental health programming, Indigenous student programming, programs for racialized students, career development programs, programs for students with disabilities, and many others (see Smith et al., in press, for a review of current Canadian programming). Fundamentally, each program is trying to make the student more comfortable, more acclimated, and more successful. The goal of these programs is to enhance academic skills, engage students and make them feel included in the school’s culture, and increase commitment to educational goals – they aim to make the student feel like they belong at the institution.

Does EDIA exist for Faculty?

Current State of EDIA in Academia

In both the US and Canada, faculty from diverse backgrounds remain under-represented in academia, both in terms of percentages in the population, and in the workforce (e.g., CAUT, 2018; Ellsworth et al., 2022). Perhaps this is not surprising given the data we highlighted above that students are not graduating from high school or attending university at the rates that would be expected given their proportion of the population. This inequity persists throughout graduate work and likely results in even fewer racialized, gender and sexually diverse, and disabled individuals achieving the credentials required to become academics. Even though 95% of research-intensive institutions in the US have a senior administrative position dedicated to diversity and inclusion, only 8% of institutions have at least equitable student representation and graduation rates, and 88% of not-for-profit colleges and universities have full time faculty that are less diverse than the US population (Ellsworth et al., 2022).

Yet, in Canada, there have been some important gains over the years (CAUT, 2018). The percentage of racialized faculty rose from 17% in 2006 to 21% in 2016, keeping pace with the percentage of racialized individuals in the population. There are more women faculty than ever before, but women, and especially racialized women, are least likely to have full-time employment positions in academia. Indigenous faculty are also underrepresented, at less than half the rate than would be expected by the number of Indigenous people in the labour force, and less than a third the rate that would be expected by population. Finally, there are clear and consistent wage gaps between non-indigenous non-racialized men and all other groups, with racialized women being the lowest paid. Further, the pace of change is slow. Ellsworth et al., 2022 report that at the current pace of change it would take 300-400 years for faculty diversity to reach parity with the US population.

Does Merit Really Exist in Academia?

As noted above, there are systematic issues that need to be dealt with for more diverse representation in faculty. Academia, and jobs in academia, have long been argued to be based on merit. Our peer-review system ensures that the people who are better at being academics (better researchers, better professors, better administrators) get the academic jobs, get tenure, get promoted, etc. But as with any general statement of value such as this, there are caveats. We don’t have to look far before we see some of the flaws in the system. The structure of merit within academia was developed at a time when (often White) male professors were the status quo, so perhaps it is no surprise that academic structures tend to work better for men (Van den Brink & Benschop, 2012). Indeed, there has been evidence that women are seen as less qualified than men to be faculty members (Bourabain, 2021; Johansson & Śliwa, 2013) which can lead to discrimination, higher standards for women, lower salaries, and slower progression though the ranks. Despite evidence to the contrary, women are considered slower to achieve their academic success (Krefting, 2003; Staub & Rafnsdóttir, 2020; Van den Brink & Benschop, 2012), which has been attributed to their family situations (i.e., having children). As such women are more likely to be asked about their family at hiring and promotion (Bourabain, 2021; Mixon & Treviño, 2005; Orbogu & Bisiriyu, 2012; Rivera, 2017; Treviño et al., 2018). Not surprisingly, these perceptions of less “value” from women academics has contributed to the well-established pay gap in academia (Bailey et al., 2016; Schulz & Tanguay, 2006; Woodhams et al., 2022).

For minorities, and women of colour in particular, realities are even worse, as they experience minimization of their skills and qualifications are questions as they are perceived to be “diversity hires” rather than “qualified” applicants (Griffin et al., 2013; Johansson & Śliwa, 2013; Maseti, 2018: Zambrana et al., 2017). Some minority faculty members have indicated that they are consistently fighting to be seen as an academic and not just as their skin colour (Johansson & Śliwa, 2013). These faculty felt that because of who they were they were held to an unfair standard (Griffin et al., 2013) of behaviour while also feeling like they need to offset stereotypes of being “angry” or “aggressive” by smiling and being mindful of their body language (Jackson, 2008).

Another issue that affects “diverse” academics is their workload related to administrative duties. Many faculty members coming from minority groups feel pressure to mentor and support the “next generation” of students who may be looking up to them as a role model (e.g., Griffin et al., 2013). Most universities and colleges in North America are also launching working groups, special projects, policy teams, etc., which specifically require membership from people representing diverse groups. As such this can add significantly to the workload of people who belong to those groups. Added to the disparagement of many academics’ experiences toward their work on diversity issues (e.g., Simpson, 2010; being told this “Niche” research is not “rigorous” enough and will therefore not help them achieve promotion and tenure) this can lead to burnout and lack of progress.

How to support diverse faculty

Employees that belong to one of more categories of having a disability, being racialized, or a sexual or gender minority have greater sense of belonging and job satisfaction in diverse and inclusive environments; But how do we create such an environment for new employees? One strategy that has been used by many academic employers in recent years is the idea of “cluster hires” (e.g., Chilton, 2020; Flaherty, 2015) though not without controversy (Sa, 2019). The basic idea is that a department (or group of departments) decide that they need to hire a diverse group of faculty in one particular area of research. The criticism of this approach (e.g., Sa, 2019) is that this forces departments to group hires into similar research areas within a small number of departments (unless institutional finances are very strong) and this could functionally act to isolate those hires into niche fields. It is certainly the case that groups of faculty hired at the same time will increase a sense of belonginess and comradery among those faculty, but it is important that cluster hires be across disciplines and across institutions to maximize benefits. In addition, continuing the approach over time as part of an institutional strategy will reduce the chances of people feeling that the hires were “tokens” (Chilton, 2020). Importantly, cluster hires should include ongoing support in terms of mentoring programs, support for faculty as they work toward tenure and promotion.

It is worth noting that even with cluster hiring, which can be effective, there must be an awareness of what is meant by “diverse” applicants. As we have highlighted above, often diversity strategies focus on “visible” diversity. Although this is clearly important, we must also be sure to create opportunities for less visibly diverse people to join the faculty ranks, including those with invisible disabilities, sexual minorities, and people with different personalities, values, and attitudes (e.g., Tabvuma et al., 2023).

Gaps in the Literature

There have been several identified gaps within the literature as it relates to EDIA that need to be further researched. As stated previously, focusing on diversity alone within this space is not going to lead to increased retention of diverse individuals. Further investigation is needed related to the practice, resources, and overall climate within PSE, as well as how faculty approach their curriculum and pedagogy. For example, experiential learning has shown to be effective in helping students develop new skills, enhance their problem-solving abilities, and gain a more in-depth understanding of lived experiences; meaning that if we diversify and create a more inclusive classroom, all students benefit within this space (Fede et al., 2018; Winsett et al., 2016). Many studies, and our own research, have found that co-curricular approaches to learning improve intellectual engagement, self-efficacy, satisfaction, and feelings of support from the institution (Kilpatrick & Wilburn, 2010; Lourens, 2014; Pasque & Murphy, 2005; Stirling & Kerr, 2015; Tabvuma et al., 2023), while simultaneously providing an inclusive space that mitigates the impacts of educational barriers (Carter-Rogers et al., 2022b). This may be because co-curricular learning helps students better understand people from different backgrounds and helps to develop relationships with their peers who are different from them (Keen & Hall, 2009). This point is key to understanding strong sense of belonging within the institution and needs to be explored further.

Yet most if not all research within this space has considered a singular axis of diversity, and has not approached the advancement of inclusion, belongingness, or diversity within higher education from an intersectional perspective. Research needs to consider how to identify the barriers related to retention and success among students who are from underrepresented populations, especially from an intersectional perspective. There is also a divide related to the implementation of policies and practices within institutions. There is little to no discussion related to the first voice experience about implementing these practices, and whether they are effective or not. Also, it should be noted that it is not the responsibility of diverse faculty or student body to implement these practices. There is need for an investigation into the impacts of tokenism and cosmetic diversity initiatives within higher education which cannot be the sole responsibility of diverse academics (which, as noted above, can lead to excessive administrative workloads). For example, one of the authors of this chapter is an Indigenous scholar, who encourages non-Indigenous colleagues to do the work needed to be active and ongoing allies, as it can be exhausting for Indigenous scholars to bear the emotional labour of convincing fellow colleagues to do the right thing and educate themselves on the ongoing and persistent discrimination of Indigenous peoples within higher education. This would be the same burden put on neurodiverse faculty continuously having to advocate for accommodations for students or other faculty, or the only Black scholar within the department being put on all committees simply because they are Black. Furthermore, to facilitate this “all on board” approach there must be a willingness to accept that non-diverse faculty may be doing good work on these issues, and have meaningful and valuable information to contribute, even when they belong to the majority.

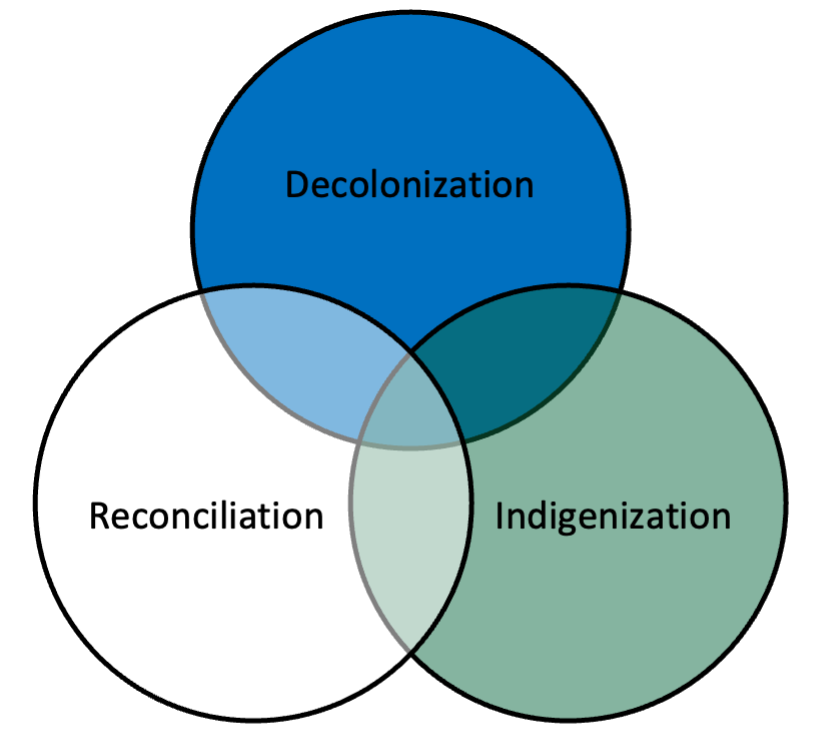

This leads to the final point of recruitment, retention, and advancement of underrepresented faculty members. In this chapter we touched on supporting diverse faculty, and the discussion around meritocratic practices within higher education, but there is a significant gap within the literature as it relates to removing the barriers that these faculty members experience. Academics are beginning to discuss the decolonization of education (see Russ Walsh and David Danto’s chapter in this volume), but there is a discourse that is emerging related to Cosmetic Indigenization (Bastien et al., 2023), and tokenized scholars (Price et al., 2024). Black scholars have discussed having to identity shift to feel like they belong, causing severe health implications (Dickens & Chavez, 2018; Dickens et al., 2019; Hall et al., 2012), and it is about time that this discussion is not just happening within the diverse academic circles. The whole academic community needs to start looking inward to how they themselves can begin implementing change within their institution.

The Future of EDIA in Higher Education

The future of EDIA in higher education is very likely to be driven by the ongoing efforts to addressing the systemic inequalities, promote diversity and inclusion, and enhance accessibility for all. Currently it makes sense that data-driven decision-making will help institutions understand the needs of diverse student and faculty populations to ensure that resources are allocated in a more efficient and effective manner. Further, by actively collaborating with diverse communities, institutions will better understand their needs and goals, which in turn helps to develop a more effective strategy for engaging and promoting EDIA.

To advance initiatives and to make change, there will need to be a commitment from senior academic leadership who must demonstrate their commitment to EDIA and ensure institutional core values are grounded in inclusive practices (Shore et al., 2018). This would mean that strategic planning would have measurable goals that are advancing EDIA, including the perceived belongingness that these individuals experience. Student success programs and funding supports are crucial for advancement of EDIA within institutions, as well as providing for the infrastructure needed for hybrid education, meetings, and health supports. Continuous evaluation of practices and constant improvements are also needed, meaning institutions need to assess effectiveness of EDIA initiatives and adapt as needed. There also needs to be engagement with community and active listening to people’s perspectives which can support informed decision making. By implementing strategies like these, institutions can create a more inclusive and accessible space within the institutional environment, ensuring that they are supporting the success and well-being of all the institutional members.

References

Astin, A. W. (1994). Higher education and the concept of community. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Astin, A. (2007). Mindworks: Becoming more conscious in an unconscious world. Charlotte: Information Age Publishing.

Axtman, K. (1998, November 23). Narrowing the path to public school diversity Federal appeals court ruling against a Boston high school that used race as a factor in admissions may reshape secondary-school policies and affect desegregation cases. The Christian Science Monitor.

Bailey, J., Peetz, D., Strachan, G., Whitehouse, G., & Broadbent, K. (2016). Academic pay loadings and gender in Australian universities. Journal of Industrial Relations, 58(5), 647-668. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022185616639308

Baker, J., & Vasseur, L. (2021). Inclusion, Diversity, Equity, & Accessibility (IDEA): Good Practices for Researchers. Retrieved from: https://brocku.ca/unesco-chair/wp-content/uploads/sites/122/ReflectionPaperIDEA.pdf on February 21, 2024.

Bastien, F., Coraiola, D. M., & Foster, W. M. (2023). Indigenous Peoples and organization studies. Organization Studies, 44(4), 659-675. https://doi.org/10.1177/01708406221141545

Brunet, S. & Galarneau, D. (2022). Profile of Canadian graduates at the bachelor level belonging to a group designated as a visible minority 2014-2017 cohorts. Statistics Canada. Retrieved from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/81-595-m/81-595-m2022003-eng.htm.

Bourabain, D. (2021). Everyday sexism and racism in the ivory tower: The experiences of early career researchers on the intersection of gender and ethnicity in the academic workplace. Gender, Work & Organization, 28(1), 248-267. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12549

Brooms, D. R. (2020). “It’s the person, but then the environment, too”: Black and Latino males’ narratives about their college successes. Sociology of Race and Ethnicity, 6(2), 195-208. https://doi.org/10.1177/2332649219884339

Carter-Rogers, K., Tabvuma, V., & Smith, S. M. (2022a). The future of inclusion is inclusive. Psynopsis, 44(4) 8-9.

Carter-Rogers, K., Tabvuma, V., Smith, S.M., Sutherland, S., & Brophy, T. (2022b). A comparative study assessing in-person and online co-curricular FYE courses in business classes. Academy of Management Proceedings. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMBPP.2022.17098abstract

CAUT (2018). Underrepresented and underpaid: Diversity and equity among Canada’s post-secondary education teachers. Canadian Association of University Teachers. Ottawa: ON.

Chambers, C. R., King, B., Myers, K. A., Millea, M., & Klein, A. (2023). Beyond the Kumbaya: A reflective case study of one university’s diversity, equity and inclusion journey. Journal of Research Administration, 54(2), 54–82.

Chilton, A., Driver, J., Masur, J. S., & Rozema, K. (2022). Assessing affirmative action’s diversity rationale. Columbia Law Review, 122(2), 331–405. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3856280

Chilton, E. (2020). The certain benefits of cluster hiring. Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved from: https://www.insidehighered.com/views/2020/02/06/how-cluster-hires-can-promote-faculty-diversity-and-inclusion-opinion.

Cukier, W. (2023). Are we there yet? 40 years of Employment Equity: The good, the bad and the ugly. Canadian Issues, 48-55.

DeRossett, T., Marler, E. K., & Hatch, H. A. (2021). The role of identification, generational status, and COVID-19 in academic success. Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Psychology. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/stl0000293

Dickens, D. D., & Chavez, E. L. (2018). Navigating the workplace: The costs and benefits of shifting identities at work among early career US Black women. Sex Roles, 78(11), 760-774.

Dickens, D. D., Womack, V. Y., & Dimes, T. (2019). Managing hypervisibility: An exploration of theory and research on identity shifting strategies in the workplace among Black women. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 113, 153-163.

Díaz-García, C., González-Moreno, A., & Jose Sáez-Martínez, F. (2013). Gender diversity within R&D teams: Its impact on radicalness of innovation. Innovation, 15(2), 149–160. https://doi.org/10.5172/impp.2013.15.2.149

Ellsworth, D, Harding, E., Law, J, & Pinder, D (2022, July 18). Racial and ethnic equity in US higher Education. McKinsey & Company. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/education/our-insights/racial-and-ethnic-equity-in-us-higher-education

Fede, J. H., Gorman, K. S., & Cimini, M. E. (2018). Student employment as a model for experiential learning. Journal of Experiential Education, 41(1), 107-124.

Ferdman, B. M. (2014). The practice of inclusion in diverse organizations: Toward a systemic and inclusive framework. In B. M. Ferdman & B. R. Deane (Eds.), Diversity at work: The practice of inclusion (pp. 3–54). Jossey-Bass/Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118764282.ch1

Flaherty, C. (2015, April 30). Cluster hiring and diversity. Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved from: https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2015/05/01/new-report-says-cluster-hiring-can-lead-increased-faculty-diversity.

Fong, C. J., Owens, S. L., Segovia, J., Hoff, M. A., & Alejandro, A. J. (2021). Indigenous cultural development and academic achievement of tribal community college students: Mediating roles of sense of belonging and support for student success. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 16(6), 709-722. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/dhe0000370

Furrie, A. (2017). Post-secondary students with disabilities: their experience – past and present. National Educational Association of Disabled Students (NEADS). Retrieved from: https://www.neads.ca/en/about/media/Final%20reportCSD2012AdeleFurrie2-3.pdf.

Gebert, D., Buengeler, C., & Heinitz, K. (2017). Tolerance: A neglected dimension in diversity training? Academy of Management Learning & Education, 16(3), 415-438.

Griffin, K. A., Bennett, J. C., & Harris, J. (2013). Marginalizing merit?: Gender differences in Black faculty D/discourses on tenure, advancement, and professional success. The Review of Higher Education, 36(4), 489-512.

Jackson, J. F. (2008). Race segregation across the academic workforce: Exploring factors that may contribute to the disparate representation of African American men. American Behavioral Scientist, 51(7), 1004-1029.

Johansson, M., & Śliwa, M. (2014). Gender, foreignness and academia: An intersectional analysis of the experiences of foreign women academics in UK business schools. Gender, Work & Organization, 21(1), 18-36.

Hall, J. C., Everett, J. E., & Hamilton-Mason, J. (2012). Black women talk about workplace stress and how they cope. Journal of Black Studies, 43(2), 207-226.

Keen, C., & Hall, K. (2009). Engaging with difference matters: Longitudinal student outcomes of co-curricular service-learning programs. The Journal of Higher Education, 80(1), 59-79.

Kelly, E., & Dobbin, F. (1998). How affirmative action became diversity management: Employer response to antidiscrimination law, 1961 to 1996. American Behavioral Scientist, 41(7), 960-984.

Kilpatrick, B. G., & Wilburn, N. L. (2010). Breaking the ice: Career development activities for accounting students. American Journal of Business Education, 3(11), 77-84.

Kirby, T. A., Russell Pascual, N., & Hildebrand, L. K. (2023). The dilution of diversity: ironic effects of broadening diversity. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 01461672231184925.

Kirby, T. A. & Zhang, J. (2024). Colorblindness and Support for Inclusion Initiatives. Paper presented at the 2024 Annual Convention of the Society for Personality and Social Psychology, February 8-10, San Diego, CA.

Krefting, L. A. (2003). Intertwined discourses of merit and gender: Evidence from academic employment in the USA. Gender, Work & Organization, 10(2), 260-278.

Layton, J (2023). First Nations Youth: Experiences and outcomes in secondary and post-secondary learning. Statistics Canada. Retrieved from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/81-599-x/81-599-x2023001-eng.htm.

Lewin, T. (1998, November 20). Affirmative Action voided at public school. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/1998/11/20/us/affirmative-action-voided-at-public-school.html

Liptak, A. (2023, June 29). Supreme Court rejects Affirmative Action programs at Harvard and U.N.C. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/06/29/us/politics/supreme-court-admissions-affirmative-action-harvard-unc.html

Lourens, A. (2014). The development of co-curricular interventions to strengthen female engineering students’ sense of self-efficacy and to improve the retention of women in traditionally male-dominated disciplines and careers. South African Journal of Industrial Engineering, 25(3), 112-125.

Maclean’s (2018, October 7). Universities with the Highest and Lowest Graduation rates. Macleans. Retrieved from: https://www.macleans.ca/education/canadian-universities-with-the-highest-and-lowest-graduation-rates/

Malone, G. P., Pillow, D. R., & Osman, A. 2012. The general belongingness scale (GBS): Assessing achieved belongingness. Personality and Individual Differences, 52(3), 311-316.

Maseti, T. (2018). The university is not your home: Lived experiences of a Black woman in academia. South African Journal of Psychology, 48(3), 343-350.

Mixon Jr, F. G., & Treviño, L. J. (2005). From kickoff to commencement: The positive role of intercollegiate athletics in higher education. Economics of Education Review, 24(1), 97- 102.

Mor Barak, M. E. (2022). Managing diversity: Toward a globally inclusive workplace. Sage Publications.

Nelson, C. E. (1996). Student diversity requires different approaches to college teaching, even in math and science. The American Behavioral Scientist, 40(2), 165–175. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764296040002007

Nishii, L. H., & Rich, R. E. (2013). Creating inclusive climates in diverse organizations. Diversity at Work: The Practice of Inclusion, 330-363.

Orbogu, C. O., & Bisiriyu, L. A. (2012). Gender issues in the recruitment and selection of academic staff in a Nigerian university. Gender and Behaviour, 10(2), 4751-4766.

Pasque, P. A., & Murphy, R. (2005). The intersections of living-learning programs and social identity as factors of academic achievement and intellectual engagement. Journal of College Student Development, 46(4), 429-441.

Price, S. T., Carter-Rogers, K., Doucette, M. B., & McKay, C. (2024). Decolonizing Business Education through Intersectional Trauma-Informed Frameworks: A CRGBA Approach to Understanding the Embodied Trauma Experiences of Tokenized Indigenous Scholars. 18th Organization Studies Workshop: Organization, Organizing, and Politics: Disciplinary Traditions and Possible Futures, May 2024, Mykonos, Greece. Russell.

Pascual, N., Kirby, T. A., & Begeny, C. T. (2024). Disentangling the nuances of diversity ideologies. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1293622.

Ray, V., & Melaku, T. M. (2023). Countering the corporate diversity backlash. MIT Sloan Management Review, 64(4), 1–3.

Rivera, L. A. (2017). When two bodies are (not) a problem: Gender and relationship status discrimination in academic hiring. American Sociological Review, 82(6), 1111-1138.

Sa, C. (2019). The precarious practice of cluster hiring. University Affairs. Retrieved from: https://universityaffairs.ca/opinion/policy-and-practice/the-precarious-practice-of-cluster-hiring/.

Savage, C. (2023, June 29). Highlights of the affirmative action opinions and dissents. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/06/29/us/politics/affirmative-action-ruling-highlights.html

Schachner, M. K., Schwarzenthal, M., Van De Vijver, F. J., & Noack, P. (2019). How all students can belong and achieve: Effects of the cultural diversity climate amongst students of immigrant and nonimmigrant background in Germany. Journal of Educational Psychology, 111(4), 703.

Schulz, E. R., & Tanguay, D. M. (2006). Merit pay in a public higher education institution: Questions of impact and attitudes. Public Personnel Management, 35(1), 77-88.

Shore, L. M., Cleveland, J. N., & Sanchez, D. (2018). Inclusive workplaces: A review and model. Human Resource Management Review, 28(2), 176-189.

Shore, L. M., Randel, A. E., Chung, B. G., Dean, M. A., Holcombe Ehrhart, K., & Singh, G. (2011). Inclusion and diversity in work groups: A review and model for future research. Journal of Management, 37(4), 1262-1289.

Skerrett, A., & Hargreaves, A. (2008). Student diversity and secondary school change in a context of increasingly standardized reform. American Educational Research Journal, 45(4), 913–945. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831208320243

Simpson, J. L. (2010). Blinded by the white: Challenging the notion of a color-blind meritocracy in the academy. Southern Communication Journal, 75(2), 150-159.

Slaten, C. D., Elison, Z. M., Deemer, E. D., Hughes, H. A., & Shemwell, D. A. (2018). The development and validation of the university belonging questionnaire. The Journal of Experimental Education, 86(4), 633-651.

Smith, S. M., Daniels, A., Brophy, T., & McEvoy, A (in press). Results of a pan-Canadian survey of FYE and SIT programming in College and University. In Smith, S. M., Brophy, T., Daniels, A., & McEvoy, A. (eds). The Evolution of First Year Experience and Students in Transition Programming in Canada: 25 Years of Belonging.

Smith, S. M., Carter-Rogers, K., & Tabvuma, V. (2022). Diversity in the workplace isn’t enough: businesses need to work toward inclusion. The Conversation Canada. Nov. 27, 2022; https://theconversation.com/diversity-in-the-workplace-isnt-enough-businesses-need-to-work-toward-inclusion-194136

Star, L. (2022). Evidence Based Inclusion; It’s Time to Focus on the Right Needle. Primedia eLaunch LLC.

Statistics Canada (2021a). Representation of men and women on boards of directors. Retrieved from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=3310021801

Statistics Canada (2021b). Study: Diversity among board directors and officers: Exploratory estimates on family, work and income. Retrieved from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/210518/dq210518b-eng.htm

Statistics Canada (2023). Postsecondary enrolments by field of study, registration status, program type, credential type, and gender. Retrieved from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=3710001101.

Staub, M., & Rafnsdóttir, G. L. (2020). Gender, agency, and time use among doctorate holders: The case of Iceland. Time & Society, 29(1), 143-165.

Stirling, A. E., & Kerr, G. A. (2015). Creating meaningful co-curricular experiences in higher education. Journal of Education & Social Policy, 2(6), 1-7.

Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. President and Fellows of Harvard College, 600 U.S. ___ (2023). https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/600/20-1199/

Tabvuma, V., Smith, S. M., & Carter-Rogers, K., (2023). Beyond visible diversity: how workplaces can encourage diverse personalities, values and attitudes. The Conversation Canada. Jan. 17, 2023; https://theconversation.com/how-workplaces-can-encourage-diverse-personalities-values-and-attitudes-197004

Tienda, M. (2013). Diversity ≠ inclusion: Promoting integration in higher education. Educational Researcher, 42(9), 467-475.

Tinto, V. (1993). Leaving College: Rethinking the Causes and Cures of Student Attrition (2nd ed.). University of Chicago Press.

Tinto, V. (2010). From theory to action: Exploring the institutional conditions for student retention. In Higher education: Handbook of theory and research, 51-89. Springer, Dordrecht.

Trawalter, S., Driskell, S., & Davidson, M. N. (2016). What is good isn’t always fair: On the unintended effects of framing diversity as good. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 16(1), 69-99.

Treisman, U. (1992). Studying students studying Calculus: A look at the lives of minority Mathematics students in College. The College Mathematics Journal, 23(5), 362–372. https://doi.org/10.2307/2686410

Treviño, L. J., Gomez-Mejia, L. R., Balkin, D. B., & Mixon Jr, F. G. (2018). Meritocracies or masculinities? The differential allocation of named professorships by gender in the academy. Journal of Management, 44(3), 972-1000.

Unzueta, M. M., & Binning, K. R. (2012). Diversity is in the eye of the beholder: How concern for the in-group affects perceptions of racial diversity. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 38(1), 26-38.

Van den Brink, M., & Benschop, Y. (2012b). Slaying the seven‐headed dragon: The quest for gender change in academia. Gender, Work & Organization, 19(1), 71-92.

Wessman S.P. p.p.a. Wessman H.R. v. Gittens R. P, Chairperson of the Boston School committee, et al., 160 F.3d 790 (1st Cir. 1998). https://law.justia.com/cases/federal/appellate-courts/F3/160/790/534051/

Winnick, S. (2010). The world’s first ” Kumbaya ” moment: New evidence about an old song. Folklife Center News, 32(3–4), 3–10. https://www.academia.edu/25314754/The_Worlds_First_Kumbaya_Moment_New_Evidence_about_an_Old_Song .

Winsett, C., Foster, C., Dearing, J., & Burch, G. (2016). The impact of group experiential learning on student engagement. Academy of Business Research Journal, 3, 7.

Woodhams, C., Trojanowski, G., & Wilkinson, K. (2022). Merit sticks to men: gender pay gaps and (In) equality at UK Russell Group Universities. Sex Roles, 86(9-10), 544-558.

Zambrana, R. E., Harvey Wingfield, A., Lapeyrouse, L. M., Davila, B. A., Hoagland, T. L., & Valdez, R. B. (2017). Blatant, subtle, and insidious: URM faculty perceptions of discriminatory practices in predominantly White institutions. Sociological Inquiry, 87(2), 207-232.

How to Cite

Carter-Rogers, K., Smith, S., Chigumba, C., & Tabvuma, V. (2024). The future of equity, diversity, inclusion, and accessibility in post-secondary education. In M. E. Norris and S. M. Smith (Eds.), Leading the Way: Envisioning the Future of Higher Education. Kingston, ON: Queen’s University, eCampus Ontario. Licensed under CC BY 4.0. Retrieved from https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/futureofhighereducation/chapter/ediapostsecondary/

About the authors

Katelynn Carter-Rogers

Steven Smith

Chiedza C. Chigumba

Vurain Tabvuma

The Future of Equity, Diversity, Inclusion, and Accessibility in Post-Secondary Education Copyright © 2024 by Katelynn Carter-Rogers; Steven M. Smith; Chiedza C. Chigumba; and Vurain Tabvuma is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Ways of Knowing and Higher Education

Ways of Knowing and Higher Education

Russ Walsh1 and David Danto2

Duquesne University

MacEwan University

Introduction

Long before beginning post-secondary education, all of us have experienced different ways of knowing. In our primary and secondary schooling we have moved between lectures and homework in math, sciences, social studies, literature, art and music – often within the same day – readily shifting from one way of thinking to another. In our social relationships we have also pursued different ways of knowing, addressing problems, projects and collaborative play that require understanding and engaging with multiple others in multiple ways. And to the extent that we’ve participated in religious or spiritual practices and communities, we have experienced knowing in yet other ways. We have in other words been fluidly engaged with multiple ways of knowing. Is this diversity evident in the academic world?

While our personal lives may still require a facility with multiple ways of knowing, our academic lives may corral us into discipline-specific discourses and ways of knowing. This results partly from the specialization that higher education facilitates – pursuing one field of study necessarily leaves others behind. And each field of study has its own history and set of viewpoints, such that to advance in one field is to acquire a particular way of thinking and talking. Higher education may also foster a discipline-specific identity. For example, a student studying computer science is called a computer science major, and it’s not all uncommon for that to become the first topic of conversation amidst undergraduate students (“what’s your major?”) as well as for graduate students and faculty. Hence, in studying sociology, one becomes a sociologist – a position with which one identifies, and through which one views their world. This indoctrination shapes one’s position with respect to knowledge.

We’ve used the word indoctrination because its history calls to mind two distinct aspects of post-secondary learning. To indoctrinate is to teach, and indoctrination is learning – at least those were the original meanings of the terms. An indoctrinated individual was a scholar with a depth and breadth of knowledge, typically across multiple disciplines. However, over time these words took on a negative connotation, with indoctrination taken to imply accepting a set of beliefs uncritically – a contraction rather than expansion of thought, with an indoctrinated individual seen as close-minded rather than receptive to alternative viewpoints (Lewin, 2022).