1

“Yes, of course, if it’s fine tomorrow,” said Mrs. Ramsay. “But you’ll

have to be up with the lark,” she added.

To her son these words conveyed an extraordinary joy, as if it were

settled, the expedition were bound to take place, and the wonder to which

he had looked forward, for years and years it seemed, was, after a night’s

darkness and a day’s sail, within touch. Since he belonged, even at the

age of six, to that great clan which cannot keep this feeling separate

from that, but must let future prospects, with their joys and sorrows,

cloud what is actually at hand, since to such people even in earliest

childhood any turn in the wheel of sensation has the power to crystallise

and transfix the moment upon which its gloom or radiance rests, James

Ramsay, sitting on the floor cutting out pictures from the illustrated

catalogue of the Army and Navy stores, endowed the picture of a

refrigerator, as his mother spoke, with heavenly bliss. It was fringed

with joy. The wheelbarrow, the lawnmower, the sound of poplar trees,

leaves whitening before rain, rooks cawing, brooms knocking, dresses

rustling–all these were so coloured and distinguished in his mind that he

had already his private code, his secret language, though he appeared the

image of stark and uncompromising severity, with his high forehead and his

fierce blue eyes, impeccably candid and pure, frowning slightly at the

sight of human frailty, so that his mother, watching him guide his

scissors neatly round the refrigerator, imagined him all red and ermine on

the Bench or directing a stern and momentous enterprise in some crisis of

public affairs.

“But,” said his father, stopping in front of the drawing-room window, “it

won’t be fine.”

Had there been an axe handy, a poker, or any weapon that would have gashed

a hole in his father’s breast and killed him, there and then, James would

have seized it. Such were the extremes of emotion that Mr. Ramsay excited

in his children’s breasts by his mere presence; standing, as now, lean as

a knife, narrow as the blade of one, grinning sarcastically, not only with

the pleasure of disillusioning his son and casting ridicule upon his wife,

who was ten thousand times better in every way than he was

(James thought), but also with some secret conceit at his own accuracy of

judgement. What he said was true. It was always true. He was incapable

of untruth; never tampered with a fact; never altered a disagreeable word

to suit the pleasure or convenience of any mortal being, least of all of

his own children, who, sprung from his loins, should be aware from

childhood that life is difficult; facts uncompromising; and the passage to

that fabled land where our brightest hopes are extinguished, our frail

barks founder in darkness (here Mr. Ramsay would straighten his back and

narrow his little blue eyes upon the horizon), one that needs, above all,

courage, truth, and the power to endure.

“But it may be fine–I expect it will be fine,” said Mrs. Ramsay, making

some little twist of the reddish brown stocking she was knitting,

impatiently. If she finished it tonight, if they did go to the Lighthouse

after all, it was to be given to the Lighthouse keeper for his little boy,

who was threatened with a tuberculous hip; together with a pile of old

magazines, and some tobacco, indeed, whatever she could find lying about,

not really wanted, but only littering the room, to give those poor

fellows, who must be bored to death sitting all day with nothing to do but

polish the lamp and trim the wick and rake about on their scrap of garden,

something to amuse them. For how would you like to be shut up for a whole

month at a time, and possibly more in stormy weather, upon a rock the size

of a tennis lawn? she would ask; and to have no letters or newspapers, and

to see nobody; if you were married, not to see your wife, not to know how

your children were,–if they were ill, if they had fallen down and broken

their legs or arms; to see the same dreary waves breaking week after week,

and then a dreadful storm coming, and the windows covered with spray, and

birds dashed against the lamp, and the whole place rocking, and not be

able to put your nose out of doors for fear of being swept into the sea?

How would you like that? she asked, addressing herself particularly to her

daughters. So she added, rather differently, one must take them whatever

comforts one can.

“It’s due west,” said the atheist Tansley, holding his bony fingers spread

so that the wind blew through them, for he was sharing Mr. Ramsay’s

evening walk up and down, up and down the terrace. That is to say, the

wind blew from the worst possible direction for landing at the Lighthouse.

Yes, he did say disagreeable things, Mrs. Ramsay admitted; it was odious

of him to rub this in, and make James still more disappointed; but at the

same time, she would not let them laugh at him. “The atheist,” they

called him; “the little atheist.” Rose mocked him; Prue mocked him;

Andrew, Jasper, Roger mocked him; even old Badger without a tooth in his

head had bit him, for being (as Nancy put it) the hundred and tenth young

man to chase them all the way up to the Hebrides when it was ever so much

nicer to be alone.

“Nonsense,” said Mrs. Ramsay, with great severity. Apart from the habit

of exaggeration which they had from her, and from the implication (which

was true) that she asked too many people to stay, and had to lodge some in

the town, she could not bear incivility to her guests, to young men in

particular, who were poor as churchmice, “exceptionally able,” her husband

said, his great admirers, and come there for a holiday. Indeed, she had

the whole of the other sex under her protection; for reasons she could not

explain, for their chivalry and valour, for the fact that they negotiated

treaties, ruled India, controlled finance; finally for an attitude towards

herself which no woman could fail to feel or to find agreeable, something

trustful, childlike, reverential; which an old woman could take from a

young man without loss of dignity, and woe betide the girl–pray Heaven it

was none of her daughters!–who did not feel the worth of it, and all

that it implied, to the marrow of her bones!

She turned with severity upon Nancy. He had not chased them, she said.

He had been asked.

They must find a way out of it all. There might be some simpler way, some

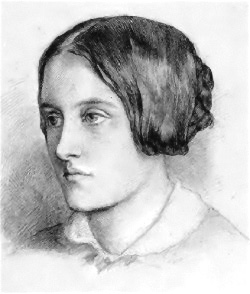

less laborious way, she sighed. When she looked in the glass and saw her

hair grey, her cheek sunk, at fifty, she thought, possibly she might have

managed things better–her husband; money; his books. But for her own

part she would never for a single second regret her decision, evade

difficulties, or slur over duties. She was now formidable to behold, and

it was only in silence, looking up from their plates, after she had spoken

so severely about Charles Tansley, that her daughters, Prue, Nancy,

Rose–could sport with infidel ideas which they had brewed for themselves

of a life different from hers; in Paris, perhaps; a wilder life; not

always taking care of some man or other; for there was in all their minds

a mute questioning of deference and chivalry, of the Bank of England and

the Indian Empire, of ringed fingers and lace, though to them all there

was something in this of the essence of beauty, which called out the

manliness in their girlish hearts, and made them, as they sat at table

beneath their mother’s eyes, honour her strange severity, her extreme

courtesy, like a queen’s raising from the mud to wash a beggar’s dirty

foot, when she admonished them so very severely about that wretched

atheist who had chased them–or, speaking accurately, been invited to

stay with them–in the Isle of Skye.

“There’ll be no landing at the Lighthouse tomorrow,” said Charles Tansley,

clapping his hands together as he stood at the window with her husband.

Surely, he had said enough. She wished they would both leave her and

James alone and go on talking. She looked at him. He was such a

miserable specimen, the children said, all humps and hollows. He couldn’t

play cricket; he poked; he shuffled. He was a sarcastic brute, Andrew

said. They knew what he liked best–to be for ever walking up and down,

up and down, with Mr. Ramsay, and saying who had won this, who had won

that, who was a “first rate man” at Latin verses, who was “brilliant but I

think fundamentally unsound,” who was undoubtedly the “ablest fellow in

Balliol,” who had buried his light temporarily at Bristol or Bedford, but

was bound to be heard of later when his Prolegomena, of which Mr. Tansley

had the first pages in proof with him if Mr. Ramsay would like to see

them, to some branch of mathematics or philosophy saw the light of day.

That was what they talked about.

She could not help laughing herself sometimes. She said, the other day,

something about “waves mountains high.” Yes, said Charles Tansley, it

was a little rough. “Aren’t you drenched to the skin?” she had said.

“Damp, not wet through,” said Mr. Tansley, pinching his sleeve, feeling

his socks.

But it was not that they minded, the children said. It was not his face;

it was not his manners. It was him–his point of view. When they talked

about something interesting, people, music, history, anything, even said

it was a fine evening so why not sit out of doors, then what they

complained of about Charles Tansley was that until he had turned the whole

thing round and made it somehow reflect himself and disparage them–he was

not satisfied. And he would go to picture galleries they said, and he

would ask one, did one like his tie? God knows, said Rose, one did not.

Disappearing as stealthily as stags from the dinner-table directly the

meal was over, the eight sons and daughters of Mr. and Mrs. Ramsay sought

their bedrooms, their fastness in a house where there was no other privacy

to debate anything, everything; Tansley’s tie; the passing of the Reform

Bill; sea birds and butterflies; people; while the sun poured into those

attics, which a plank alone separated from each other so that every

footstep could be plainly heard and the Swiss girl sobbing for her father

who was dying of cancer in a valley of the Grisons, and lit up bats,

flannels, straw hats, ink-pots, paint-pots, beetles, and the skulls of

small birds, while it drew from the long frilled strips of seaweed pinned

to the wall a smell of salt and weeds, which was in the towels too,

gritty with sand from bathing.

Strife, divisions, difference of opinion, prejudices twisted into the very

fibre of being, oh, that they should begin so early, Mrs. Ramsay deplored.

They were so critical, her children. They talked such nonsense. She went

from the dining-room, holding James by the hand, since he would not go

with the others. It seemed to her such nonsense–inventing differences,

when people, heaven knows, were different enough without that. The real

differences, she thought, standing by the drawing-room window, are enough,

quite enough. She had in mind at the moment, rich and poor, high and low;

the great in birth receiving from her, half grudging, some respect, for

had she not in her veins the blood of that very noble, if slightly

mythical, Italian house, whose daughters, scattered about English

drawing-rooms in the nineteenth century, had lisped so charmingly, had

stormed so wildly, and all her wit and her bearing and her temper came

from them, and not from the sluggish English, or the cold Scotch; but more

profoundly, she ruminated the other problem, of rich and poor, and the

things she saw with her own eyes, weekly, daily, here or in London, when

she visited this widow, or that struggling wife in person with a bag on

her arm, and a note-book and pencil with which she wrote down in columns

carefully ruled for the purpose wages and spendings, employment and

unemployment, in the hope that thus she would cease to be a private woman

whose charity was half a sop to her own indignation, half a relief to her

own curiosity, and become what with her untrained mind she greatly

admired, an investigator, elucidating the social problem.

Insoluble questions they were, it seemed to her, standing there, holding

James by the hand. He had followed her into the drawing-room, that young

man they laughed at; he was standing by the table, fidgeting with

something, awkwardly, feeling himself out of things, as she knew without

looking round. They had all gone–the children; Minta Doyle and Paul

Rayley; Augustus Carmichael; her husband–they had all gone. So she

turned with a sigh and said, “Would it bore you to come with me,

Mr. Tansley?”

She had a dull errand in the town; she had a letter or two to write; she

would be ten minutes perhaps; she would put on her hat. And, with her

basket and her parasol, there she was again, ten minutes later, giving out

a sense of being ready, of being equipped for a jaunt, which, however, she

must interrupt for a moment, as they passed the tennis lawn, to ask

Mr. Carmichael, who was basking with his yellow cat’s eyes ajar, so that

like a cat’s they seemed to reflect the branches moving or the clouds

passing, but to give no inkling of any inner thoughts or emotion

whatsoever, if he wanted anything.

For they were making the great expedition, she said, laughing. They were

going to the town. “Stamps, writing-paper, tobacco?” she suggested,

stopping by his side. But no, he wanted nothing. His hands clasped

themselves over his capacious paunch, his eyes blinked, as if he would

have liked to reply kindly to these blandishments (she was seductive but a

little nervous) but could not, sunk as he was in a grey-green somnolence

which embraced them all, without need of words, in a vast and benevolent

lethargy of well-wishing; all the house; all the world; all the people in

it, for he had slipped into his glass at lunch a few drops of something,

which accounted, the children thought, for the vivid streak of

canary-yellow in moustache and beard that were otherwise milk white. No,

nothing, he murmured.

He should have been a great philosopher, said Mrs. Ramsay, as they went

down the road to the fishing village, but he had made an unfortunate

marriage. Holding her black parasol very erect, and moving with an

indescribable air of expectation, as if she were going to meet some one

round the corner, she told the story; an affair at Oxford with some girl;

an early marriage; poverty; going to India; translating a little poetry

“very beautifully, I believe,” being willing to teach the boys Persian or

Hindustanee, but what really was the use of that?–and then lying, as they

saw him, on the lawn.

It flattered him; snubbed as he had been, it soothed him that Mrs. Ramsay

should tell him this. Charles Tansley revived. Insinuating, too, as she

did the greatness of man’s intellect, even in its decay, the subjection of

all wives–not that she blamed the girl, and the marriage had been happy

enough, she believed–to their husband’s labours, she made him feel better

pleased with himself than he had done yet, and he would have liked, had

they taken a cab, for example, to have paid the fare. As for her little

bag, might he not carry that? No, no, she said, she always carried that

herself. She did too. Yes, he felt that in her. He felt many things,

something in particular that excited him and disturbed him for reasons

which he could not give. He would like her to see him, gowned and hooded,

walking in a procession. A fellowship, a professorship, he felt capable

of anything and saw himself–but what was she looking at? At a man

pasting a bill. The vast flapping sheet flattened itself out, and each

shove of the brush revealed fresh legs, hoops, horses, glistening reds and

blues, beautifully smooth, until half the wall was covered with the

advertisement of a circus; a hundred horsemen, twenty performing seals,

lions, tigers … Craning forwards, for she was short-sighted, she read it

out … “will visit this town,” she read. It was terribly dangerous work

for a one-armed man, she exclaimed, to stand on top of a ladder like

that–his left arm had been cut off in a reaping machine two years ago.

“Let us all go!” she cried, moving on, as if all those riders and horses

had filled her with childlike exultation and made her forget her pity.

“Let’s go,” he said, repeating her words, clicking them out, however, with

a self-consciousness that made her wince. “Let us all go to the circus.”

No. He could not say it right. He could not feel it right. But why not?

she wondered. What was wrong with him then? She liked him warmly, at the

moment. Had they not been taken, she asked, to circuses when they were

children? Never, he answered, as if she asked the very thing he wanted;

had been longing all these days to say, how they did not go to circuses.

It was a large family, nine brothers and sisters, and his father was a

working man. “My father is a chemist, Mrs. Ramsay. He keeps a shop.” He

himself had paid his own way since he was thirteen. Often he went without

a greatcoat in winter. He could never “return hospitality” (those were

his parched stiff words) at college. He had to make things last twice the

time other people did; he smoked the cheapest tobacco; shag; the same the

old men did in the quays. He worked hard–seven hours a day; his subject

was now the influence of something upon somebody–they were walking on and

Mrs. Ramsay did not quite catch the meaning, only the words, here and

there … dissertation … fellowship … readership … lectureship. She

could not follow the ugly academic jargon, that rattled itself off so

glibly, but said to herself that she saw now why going to the circus had

knocked him off his perch, poor little man, and why he came out,

instantly, with all that about his father and mother and brothers and

sisters, and she would see to it that they didn’t laugh at him any more;

she would tell Prue about it. What he would have liked, she supposed,

would have been to say how he had gone not to the circus but to Ibsen with

the Ramsays. He was an awful prig–oh yes, an insufferable bore. For,

though they had reached the town now and were in the main street, with

carts grinding past on the cobbles, still he went on talking, about

settlements, and teaching, and working men, and helping our own class,

and lectures, till she gathered that he had got back entire

self-confidence, had recovered from the circus, and was about (and now

again she liked him warmly) to tell her–but here, the houses falling

away on both sides, they came out on the quay, and the whole bay

spread before them and Mrs. Ramsay could not help exclaiming, “Oh,

how beautiful!” For the great plateful of blue water was before her;

the hoary Lighthouse, distant, austere, in the midst; and on the right,

as far as the eye could see, fading and falling, in soft low pleats,

the green sand dunes with the wild flowing grasses on them, which always

seemed to be running away into some moon country, uninhabited of men.

That was the view, she said, stopping, growing greyer-eyed, that her

husband loved.

She paused a moment. But now, she said, artists had come here. There

indeed, only a few paces off, stood one of them, in Panama hat and yellow

boots, seriously, softly, absorbedly, for all that he was watched by ten

little boys, with an air of profound contentment on his round red face

gazing, and then, when he had gazed, dipping; imbuing the tip of his

brush in some soft mound of green or pink. Since Mr. Paunceforte had been

there, three years before, all the pictures were like that, she said,

green and grey, with lemon-coloured sailing-boats, and pink women on the

beach.

But her grandmother’s friends, she said, glancing discreetly as they

passed, took the greatest pains; first they mixed their own colours, and

then they ground them, and then they put damp cloths to keep them moist.

So Mr. Tansley supposed she meant him to see that that man’s picture was

skimpy, was that what one said? The colours weren’t solid? Was that what

one said? Under the influence of that extraordinary emotion which had been

growing all the walk, had begun in the garden when he had wanted to take

her bag, had increased in the town when he had wanted to tell her

everything about himself, he was coming to see himself, and everything he

had ever known gone crooked a little. It was awfully strange.

There he stood in the parlour of the poky little house where she had taken

him, waiting for her, while she went upstairs a moment to see a woman. He

heard her quick step above; heard her voice cheerful, then low; looked at

the mats, tea-caddies, glass shades; waited quite impatiently; looked

forward eagerly to the walk home; determined to carry her bag; then heard

her come out; shut a door; say they must keep the windows open and the

doors shut, ask at the house for anything they wanted (she must be talking

to a child) when, suddenly, in she came, stood for a moment silent (as if

she had been pretending up there, and for a moment let herself be now),

stood quite motionless for a moment against a picture of Queen Victoria

wearing the blue ribbon of the Garter; when all at once he realised that

it was this: it was this:–she was the most beautiful person he had ever

seen.

With stars in her eyes and veils in her hair, with cyclamen and wild

violets–what nonsense was he thinking? She was fifty at least; she had

eight children. Stepping through fields of flowers and taking to her

breast buds that had broken and lambs that had fallen; with the stars in

her eyes and the wind in her hair–He had hold of her bag.

“Good-bye, Elsie,” she said, and they walked up the street, she holding

her parasol erect and walking as if she expected to meet some one round

the corner, while for the first time in his life Charles Tansley felt an

extraordinary pride; a man digging in a drain stopped digging and looked

at her, let his arm fall down and looked at her; for the first time in his

life Charles Tansley felt an extraordinary pride; felt the wind and the

cyclamen and the violets for he was walking with a beautiful woman. He

had hold of her bag.

2

“No going to the Lighthouse, James,” he said, as trying in deference to

Mrs. Ramsay to soften his voice into some semblance of geniality at least.

Odious little man, thought Mrs. Ramsay, why go on saying that?

3

“Perhaps you will wake up and find the sun shining and the birds singing,”

she said compassionately, smoothing the little boy’s hair, for her

husband, with his caustic saying that it would not be fine, had dashed his

spirits she could see. This going to the Lighthouse was a passion of his,

she saw, and then, as if her husband had not said enough, with his caustic

saying that it would not be fine tomorrow, this odious little man went and

rubbed it in all over again.

“Perhaps it will be fine tomorrow,” she said, smoothing his hair.

All she could do now was to admire the refrigerator, and turn the pages of

the Stores list in the hope that she might come upon something like a

rake, or a mowing-machine, which, with its prongs and its handles, would

need the greatest skill and care in cutting out. All these young men

parodied her husband, she reflected; he said it would rain; they said it

would be a positive tornado.

But here, as she turned the page, suddenly her search for the picture of a

rake or a mowing-machine was interrupted. The gruff murmur, irregularly

broken by the taking out of pipes and the putting in of pipes which had

kept on assuring her, though she could not hear what was said (as she sat

in the window which opened on the terrace), that the men were happily

talking; this sound, which had lasted now half an hour and had taken its

place soothingly in the scale of sounds pressing on top of her, such as

the tap of balls upon bats, the sharp, sudden bark now and then,

“How’s that? How’s that?” of the children playing cricket, had ceased;

so that the monotonous fall of the waves on the beach, which for the most

part beat a measured and soothing tattoo to her thoughts and seemed

consolingly to repeat over and over again as she sat with the children

the words of some old cradle song, murmured by nature, “I am guarding

you–I am your support,” but at other times suddenly and unexpectedly,

especially when her mind raised itself slightly from the task actually in

hand, had no such kindly meaning, but like a ghostly roll of drums

remorselessly beat the measure of life, made one think of the destruction

of the island and its engulfment in the sea, and warned her whose day had

slipped past in one quick doing after another that it was all ephemeral as

a rainbow–this sound which had been obscured and concealed under the

other sounds suddenly thundered hollow in her ears and made her look up

with an impulse of terror.

They had ceased to talk; that was the explanation. Falling in one second

from the tension which had gripped her to the other extreme which, as if

to recoup her for her unnecessary expense of emotion, was cool, amused,

and even faintly malicious, she concluded that poor Charles Tansley had

been shed. That was of little account to her. If her husband required

sacrifices (and indeed he did) she cheerfully offered up to him Charles

Tansley, who had snubbed her little boy.

One moment more, with her head raised, she listened, as if she waited for

some habitual sound, some regular mechanical sound; and then, hearing

something rhythmical, half said, half chanted, beginning in the garden, as

her husband beat up and down the terrace, something between a croak and a

song, she was soothed once more, assured again that all was well, and

looking down at the book on her knee found the picture of a pocket knife

with six blades which could only be cut out if James was very careful.

Suddenly a loud cry, as of a sleep-walker, half roused, something about

Stormed at with shot and shell

sung out with the utmost intensity in her ear, made her turn

apprehensively to see if anyone had heard him. Only Lily Briscoe, she was

glad to find; and that did not matter. But the sight of the girl standing

on the edge of the lawn painting reminded her; she was supposed to be

keeping her head as much in the same position as possible for Lily’s

picture. Lily’s picture! Mrs. Ramsay smiled. With her little Chinese

eyes and her puckered-up face, she would never marry; one could not take

her painting very seriously; she was an independent little creature, and

Mrs. Ramsay liked her for it; so, remembering her promise, she bent her

head.

4

Indeed, he almost knocked her easel over, coming down upon her with his

hands waving shouting out, “Boldly we rode and well,” but, mercifully, he

turned sharp, and rode off, to die gloriously she supposed upon the

heights of Balaclava. Never was anybody at once so ridiculous and so

alarming. But so long as he kept like that, waving, shouting, she was

safe; he would not stand still and look at her picture. And that was what

Lily Briscoe could not have endured. Even while she looked at the mass,

at the line, at the colour, at Mrs. Ramsay sitting in the window with

James, she kept a feeler on her surroundings lest some one should creep

up, and suddenly she should find her picture looked at. But now, with all

her senses quickened as they were, looking, straining, till the colour of

the wall and the jacmanna beyond burnt into her eyes, she was aware of

someone coming out of the house, coming towards her; but somehow divined,

from the footfall, William Bankes, so that though her brush quivered, she

did not, as she would have done had it been Mr. Tansley, Paul Rayley,

Minta Doyle, or practically anybody else, turn her canvas upon the grass,

but let it stand. William Bankes stood beside her.

They had rooms in the village, and so, walking in, walking out, parting

late on door-mats, had said little things about the soup, about the

children, about one thing and another which made them allies; so that when

he stood beside her now in his judicial way (he was old enough to be her

father too, a botanist, a widower, smelling of soap, very scrupulous and

clean) she just stood there. He just stood there. Her shoes were

excellent, he observed. They allowed the toes their natural expansion.

Lodging in the same house with her, he had noticed too, how orderly she

was, up before breakfast and off to paint, he believed, alone: poor,

presumably, and without the complexion or the allurement of Miss Doyle

certainly, but with a good sense which made her in his eyes superior to

that young lady. Now, for instance, when Ramsay bore down on them,

shouting, gesticulating, Miss Briscoe, he felt certain, understood.

Some one had blundered.

Mr. Ramsay glared at them. He glared at them without seeming to see them.

That did make them both vaguely uncomfortable. Together they had seen a

thing they had not been meant to see. They had encroached upon a privacy.

So, Lily thought, it was probably an excuse of his for moving, for getting

out of earshot, that made Mr. Bankes almost immediately say something

about its being chilly and suggested taking a stroll. She would come,

yes. But it was with difficulty that she took her eyes off her picture.

The jacmanna was bright violet; the wall staring white. She would not

have considered it honest to tamper with the bright violet and the staring

white, since she saw them like that, fashionable though it was, since

Mr. Paunceforte’s visit, to see everything pale, elegant, semitransparent.

Then beneath the colour there was the shape. She could see it all so

clearly, so commandingly, when she looked: it was when she took her brush

in hand that the whole thing changed. It was in that moment’s flight

between the picture and her canvas that the demons set on her who often

brought her to the verge of tears and made this passage from conception to

work as dreadful as any down a dark passage for a child. Such she often

felt herself–struggling against terrific odds to maintain her courage; to

say: “But this is what I see; this is what I see,” and so to clasp some

miserable remnant of her vision to her breast, which a thousand forces did

their best to pluck from her. And it was then too, in that chill and

windy way, as she began to paint, that there forced themselves upon her

other things, her own inadequacy, her insignificance, keeping house for

her father off the Brompton Road, and had much ado to control her impulse

to fling herself (thank Heaven she had always resisted so far) at

Mrs. Ramsay’s knee and say to her–but what could one say to her? “I’m in

love with you?” No, that was not true. “I’m in love with this all,”

waving her hand at the hedge, at the house, at the children. It was

absurd, it was impossible. So now she laid her brushes neatly in the box,

side by side, and said to William Bankes:

“It suddenly gets cold. The sun seems to give less heat,” she said,

looking about her, for it was bright enough, the grass still a soft deep

green, the house starred in its greenery with purple passion flowers, and

rooks dropping cool cries from the high blue. But something moved,

flashed, turned a silver wing in the air. It was September after all,

the middle of September, and past six in the evening. So off they

strolled down the garden in the usual direction, past the tennis lawn,

past the pampas grass, to that break in the thick hedge, guarded by red

hot pokers like brasiers of clear burning coal, between which the blue

waters of the bay looked bluer than ever.

They came there regularly every evening drawn by some need. It was as if

the water floated off and set sailing thoughts which had grown stagnant on

dry land, and gave to their bodies even some sort of physical relief.

First, the pulse of colour flooded the bay with blue, and the heart

expanded with it and the body swam, only the next instant to be checked

and chilled by the prickly blackness on the ruffled waves. Then, up

behind the great black rock, almost every evening spurted irregularly, so

that one had to watch for it and it was a delight when it came, a fountain

of white water; and then, while one waited for that, one watched, on the

pale semicircular beach, wave after wave shedding again and again

smoothly, a film of mother of pearl.

They both smiled, standing there. They both felt a common hilarity,

excited by the moving waves; and then by the swift cutting race of a

sailing boat, which, having sliced a curve in the bay, stopped; shivered;

let its sails drop down; and then, with a natural instinct to complete the

picture, after this swift movement, both of them looked at the dunes

far away, and instead of merriment felt come over them some

sadness–because the thing was completed partly, and partly because

distant views seem to outlast by a million years (Lily thought) the gazer

and to be communing already with a sky which beholds an earth entirely

at rest.

Looking at the far sand hills, William Bankes thought of Ramsay: thought

of a road in Westmorland, thought of Ramsay striding along a road by

himself hung round with that solitude which seemed to be his natural air.

But this was suddenly interrupted, William Bankes remembered (and this

must refer to some actual incident), by a hen, straddling her wings out in

protection of a covey of little chicks, upon which Ramsay, stopping,

pointed his stick and said “Pretty–pretty,” an odd illumination in to

his heart, Bankes had thought it, which showed his simplicity, his

sympathy with humble things; but it seemed to him as if their friendship

had ceased, there, on that stretch of road. After that, Ramsay had

married. After that, what with one thing and another, the pulp had gone

out of their friendship. Whose fault it was he could not say, only, after

a time, repetition had taken the place of newness. It was to repeat that

they met. But in this dumb colloquy with the sand dunes he maintained

that his affection for Ramsay had in no way diminished; but there, like

the body of a young man laid up in peat for a century, with the red fresh

on his lips, was his friendship, in its acuteness and reality, laid up

across the bay among the sandhills.

He was anxious for the sake of this friendship and perhaps too in order to

clear himself in his own mind from the imputation of having dried and

shrunk–for Ramsay lived in a welter of children, whereas Bankes was

childless and a widower–he was anxious that Lily Briscoe should not

disparage Ramsay (a great man in his own way) yet should understand how

things stood between them. Begun long years ago, their friendship had

petered out on a Westmorland road, where the hen spread her wings before

her chicks; after which Ramsay had married, and their paths lying

different ways, there had been, certainly for no one’s fault, some

tendency, when they met, to repeat.

Yes. That was it. He finished. He turned from the view. And, turning

to walk back the other way, up the drive, Mr. Bankes was alive to things

which would not have struck him had not those sandhills revealed to him

the body of his friendship lying with the red on its lips laid up in

peat–for instance, Cam, the little girl, Ramsay’s youngest daughter. She

was picking Sweet Alice on the bank. She was wild and fierce. She would

not “give a flower to the gentleman” as the nursemaid told her.

No! no! no! she would not! She clenched her fist. She stamped. And

Mr. Bankes felt aged and saddened and somehow put into the wrong by her

about his friendship. He must have dried and shrunk.

The Ramsays were not rich, and it was a wonder how they managed to

contrive it all. Eight children! To feed eight children on philosophy!

Here was another of them, Jasper this time, strolling past, to have a shot

at a bird, he said, nonchalantly, swinging Lily’s hand like a pump-handle

as he passed, which caused Mr. Bankes to say, bitterly, how she was a

favourite. There was education now to be considered (true, Mrs. Ramsay

had something of her own perhaps) let alone the daily wear and tear of

shoes and stockings which those “great fellows,” all well grown, angular,

ruthless youngsters, must require. As for being sure which was which, or

in what order they came, that was beyond him. He called them privately

after the Kings and Queens of England; Cam the Wicked, James the Ruthless,

Andrew the Just, Prue the Fair–for Prue would have beauty, he thought,

how could she help it?–and Andrew brains. While he walked up the drive

and Lily Briscoe said yes and no and capped his comments (for she was in

love with them all, in love with this world) he weighed Ramsay’s case,

commiserated him, envied him, as if he had seen him divest himself of all

those glories of isolation and austerity which crowned him in youth to

cumber himself definitely with fluttering wings and clucking

domesticities. They gave him something–William Bankes acknowledged that;

it would have been pleasant if Cam had stuck a flower in his coat or

clambered over his shoulder, as over her father’s, to look at a picture

of Vesuvius in eruption; but they had also, his old friends could not but

feel, destroyed something. What would a stranger think now? What did

this Lily Briscoe think? Could one help noticing that habits grew on him?

eccentricities, weaknesses perhaps? It was astonishing that a man of his

intellect could stoop so low as he did–but that was too harsh a

phrase–could depend so much as he did upon people’s praise.

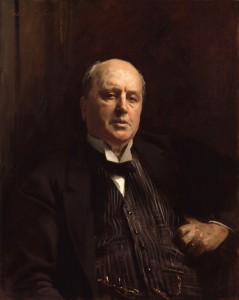

“Oh, but,” said Lily, “think of his work!”

Whenever she “thought of his work” she always saw clearly before her a

large kitchen table. It was Andrew’s doing. She asked him what his

father’s books were about. “Subject and object and the nature of

reality,” Andrew had said. And when she said Heavens, she had no notion

what that meant. “Think of a kitchen table then,” he told her, “when

you’re not there.”

So now she always saw, when she thought of Mr. Ramsay’s work, a scrubbed

kitchen table. It lodged now in the fork of a pear tree, for they had

reached the orchard. And with a painful effort of concentration, she

focused her mind, not upon the silver-bossed bark of the tree, or upon its

fish-shaped leaves, but upon a phantom kitchen table, one of those

scrubbed board tables, grained and knotted, whose virtue seems to have

been laid bare by years of muscular integrity, which stuck there, its four

legs in air. Naturally, if one’s days were passed in this seeing of

angular essences, this reducing of lovely evenings, with all their

flamingo clouds and blue and silver to a white deal four-legged table

(and it was a mark of the finest minds to do so), naturally one could not

be judged like an ordinary person.

Mr. Bankes liked her for bidding him “think of his work.” He had thought

of it, often and often. Times without number, he had said, “Ramsay is one

of those men who do their best work before they are forty.” He had made a

definite contribution to philosophy in one little book when he was only

five and twenty; what came after was more or less amplification,

repetition. But the number of men who make a definite contribution to

anything whatsoever is very small, he said, pausing by the pear tree, well

brushed, scrupulously exact, exquisitely judicial. Suddenly, as if the

movement of his hand had released it, the load of her accumulated

impressions of him tilted up, and down poured in a ponderous avalanche all

she felt about him. That was one sensation. Then up rose in a fume the

essence of his being. That was another. She felt herself transfixed

by the intensity of her perception; it was his severity; his goodness. I

respect you (she addressed silently him in person) in every atom; you are

not vain; you are entirely impersonal; you are finer than Mr. Ramsay; you

are the finest human being that I know; you have neither wife nor child

(without any sexual feeling, she longed to cherish that loneliness), you

live for science (involuntarily, sections of potatoes rose before her

eyes); praise would be an insult to you; generous, pure-hearted, heroic

man! But simultaneously, she remembered how he had brought a valet all

the way up here; objected to dogs on chairs; would prose for hours (until

Mr. Ramsay slammed out of the room) about salt in vegetables and the

iniquity of English cooks.

How then did it work out, all this? How did one judge people, think of

them? How did one add up this and that and conclude that it was liking

one felt or disliking? And to those words, what meaning attached, after

all? Standing now, apparently transfixed, by the pear tree, impressions

poured in upon her of those two men, and to follow her thought was like

following a voice which speaks too quickly to be taken down by one’s

pencil, and the voice was her own voice saying without prompting

undeniable, everlasting, contradictory things, so that even the

fissures and humps on the bark of the pear tree were irrevocably

fixed there for eternity. You have greatness, she continued, but

Mr. Ramsay has none of it. He is petty, selfish, vain, egotistical; he is

spoilt; he is a tyrant; he wears Mrs. Ramsay to death; but he has what you

(she addressed Mr. Bankes) have not; a fiery unworldliness; he knows

nothing about trifles; he loves dogs and his children. He has eight.

Mr. Bankes has none. Did he not come down in two coats the other night

and let Mrs. Ramsay trim his hair into a pudding basin? All of this

danced up and down, like a company of gnats, each separate but all

marvellously controlled in an invisible elastic net–danced up and down in

Lily’s mind, in and about the branches of the pear tree, where still hung

in effigy the scrubbed kitchen table, symbol of her profound respect for

Mr. Ramsay’s mind, until her thought which had spun quicker and quicker

exploded of its own intensity; she felt released; a shot went off close at

hand, and there came, flying from its fragments, frightened, effusive,

tumultuous, a flock of starlings.

“Jasper!” said Mr. Bankes. They turned the way the starlings flew, over

the terrace. Following the scatter of swift-flying birds in the sky they

stepped through the gap in the high hedge straight into Mr. Ramsay, who

boomed tragically at them, “Some one had blundered!”

His eyes, glazed with emotion, defiant with tragic intensity, met theirs

for a second, and trembled on the verge of recognition; but then, raising

his hand, half-way to his face as if to avert, to brush off, in an agony

of peevish shame, their normal gaze, as if he begged them to withhold for

a moment what he knew to be inevitable, as if he impressed upon them his

own child-like resentment of interruption, yet even in the moment of

discovery was not to be routed utterly, but was determined to hold fast to

something of this delicious emotion, this impure rhapsody of which he was

ashamed, but in which he revelled–he turned abruptly, slammed his private

door on them; and, Lily Briscoe and Mr. Bankes, looking uneasily up into

the sky, observed that the flock of starlings which Jasper had routed with

his gun had settled on the tops of the elm trees.

5

“And even if it isn’t fine tomorrow,” said Mrs. Ramsay, raising her eyes

to glance at William Bankes and Lily Briscoe as they passed, “it will be

another day. And now,” she said, thinking that Lily’s charm was her

Chinese eyes, aslant in her white, puckered little face, but it would take

a clever man to see it, “and now stand up, and let me measure your leg,”

for they might go to the Lighthouse after all, and she must see if the

stocking did not need to be an inch or two longer in the leg.

Smiling, for it was an admirable idea, that had flashed upon her this very

second–William and Lily should marry–she took the heather-mixture

stocking, with its criss-cross of steel needles at the mouth of it, and

measured it against James’s leg.

“My dear, stand still,” she said, for in his jealousy, not liking to serve

as measuring block for the Lighthouse keeper’s little boy, James fidgeted

purposely; and if he did that, how could she see, was it too long, was it

too short? she asked.

She looked up–what demon possessed him, her youngest, her cherished?–and

saw the room, saw the chairs, thought them fearfully shabby. Their

entrails, as Andrew said the other day, were all over the floor; but then

what was the point, she asked, of buying good chairs to let them spoil up

here all through the winter when the house, with only one old woman to see

to it, positively dripped with wet? Never mind, the rent was precisely

twopence half-penny; the children loved it; it did her husband good to be

three thousand, or if she must be accurate, three hundred miles from his

libraries and his lectures and his disciples; and there was room for

visitors. Mats, camp beds, crazy ghosts of chairs and tables whose London

life of service was done–they did well enough here; and a photograph or

two, and books. Books, she thought, grew of themselves. She never had

time to read them. Alas! even the books that had been given her and

inscribed by the hand of the poet himself: “For her whose wishes must be

obeyed” … “The happier Helen of our days” … disgraceful to say, she

had never read them. And Croom on the Mind and Bates on the Savage

Customs of Polynesia (“My dear, stand still,” she said)–neither of those

could one send to the Lighthouse. At a certain moment, she supposed, the

house would become so shabby that something must be done. If they could

be taught to wipe their feet and not bring the beach in with them–that

would be something. Crabs, she had to allow, if Andrew really wished to

dissect them, or if Jasper believed that one could make soup from seaweed,

one could not prevent it; or Rose’s objects–shells, reeds, stones; for

they were gifted, her children, but all in quite different ways. And the

result of it was, she sighed, taking in the whole room from floor to

ceiling, as she held the stocking against James’s leg, that things got

shabbier and got shabbier summer after summer. The mat was fading; the

wall-paper was flapping. You couldn’t tell any more that those were roses

on it. Still, if every door in a house is left perpetually open, and no

lockmaker in the whole of Scotland can mend a bolt, things must spoil.

What was the use of flinging a green Cashmere shawl over the edge of

a picture frame? In two weeks it would be the colour of pea soup.

But it was the doors that annoyed her; every door was left open.

She listened. The drawing-room door was open; the hall door was open;

it sounded as if the bedroom doors were open; and certainly the window

on the landing was open, for that she had opened herself. That windows

should be open, and doors shut–simple as it was, could none of them

remember it? She would go into the maids’ bedrooms at night and find

them sealed like ovens, except for Marie’s, the Swiss girl, who

would rather go without a bath than without fresh air, but then

at home, she had said, “the mountains are so beautiful.” She had said

that last night looking out of the window with tears in her eyes.

“The mountains are so beautiful.” Her father was dying there,

Mrs. Ramsay knew. He was leaving them fatherless. Scolding and

demonstrating (how to make a bed, how to open a window, with hands that

shut and spread like a Frenchwoman’s) all had folded itself quietly about

her, when the girl spoke, as, after a flight through the sunshine the

wings of a bird fold themselves quietly and the blue of its plumage

changes from bright steel to soft purple. She had stood there silent for

there was nothing to be said. He had cancer of the throat. At the

recollection–how she had stood there, how the girl had said, “At home the

mountains are so beautiful,” and there was no hope, no hope whatever, she

had a spasm of irritation, and speaking sharply, said to James:

“Stand still. Don’t be tiresome,” so that he knew instantly that her

severity was real, and straightened his leg and she measured it.

The stocking was too short by half an inch at least, making allowance for

the fact that Sorley’s little boy would be less well grown than James.

“It’s too short,” she said, “ever so much too short.”

Never did anybody look so sad. Bitter and black, half-way down, in the

darkness, in the shaft which ran from the sunlight to the depths, perhaps

a tear formed; a tear fell; the waters swayed this way and that, received

it, and were at rest. Never did anybody look so sad.

But was it nothing but looks, people said? What was there behind it–her

beauty and splendour? Had he blown his brains out, they asked, had he

died the week before they were married–some other, earlier lover, of whom

rumours reached one? Or was there nothing? nothing but an incomparable

beauty which she lived behind, and could do nothing to disturb? For

easily though she might have said at some moment of intimacy when stories

of great passion, of love foiled, of ambition thwarted came her way how

she too had known or felt or been through it herself, she never spoke.

She was silent always. She knew then–she knew without having learnt.

Her simplicity fathomed what clever people falsified. Her singleness of

mind made her drop plumb like a stone, alight exact as a bird, gave her,

naturally, this swoop and fall of the spirit upon truth which delighted,

eased, sustained–falsely perhaps.

(“Nature has but little clay,” said Mr. Bankes once, much moved by her

voice on the telephone, though she was only telling him a fact about a

train, “like that of which she moulded you.” He saw her at the end of the

line, Greek, blue-eyed, straight-nosed. How incongruous it seemed to be

telephoning to a woman like that. The Graces assembling seemed to have

joined hands in meadows of asphodel to compose that face. Yes, he would

catch the 10:30 at Euston.

“But she’s no more aware of her beauty than a child,” said Mr. Bankes,

replacing the receiver and crossing the room to see what progress the

workmen were making with an hotel which they were building at the back of

his house. And he thought of Mrs. Ramsay as he looked at that stir among

the unfinished walls. For always, he thought, there was something

incongruous to be worked into the harmony of her face. She clapped a

deer-stalker’s hat on her head; she ran across the lawn in galoshes to

snatch a child from mischief. So that if it was her beauty merely that

one thought of, one must remember the quivering thing, the living thing

(they were carrying bricks up a little plank as he watched them), and work

it into the picture; or if one thought of her simply as a woman, one must

endow her with some freak of idiosyncrasy–she did not like admiration–or

suppose some latent desire to doff her royalty of form as if her beauty

bored her and all that men say of beauty, and she wanted only to be like

other people, insignificant. He did not know. He did not know. He must

go to his work.)

Knitting her reddish-brown hairy stocking, with her head outlined absurdly

by the gilt frame, the green shawl which she had tossed over the edge of

the frame, and the authenticated masterpiece by Michael Angelo,

Mrs. Ramsay smoothed out what had been harsh in her manner a moment

before, raised his head, and kissed her little boy on the forehead.

“Let us find another picture to cut out,” she said.

6

But what had happened?

Some one had blundered.

Starting from her musing she gave meaning to words which she had held

meaningless in her mind for a long stretch of time. “Some one had

blundered”–Fixing her short-sighted eyes upon her husband, who was now

bearing down upon her, she gazed steadily until his closeness revealed to

her (the jingle mated itself in her head) that something had happened,

some one had blundered. But she could not for the life of her think what.

He shivered; he quivered. All his vanity, all his satisfaction in his own

splendour, riding fell as a thunderbolt, fierce as a hawk at the head of

his men through the valley of death, had been shattered, destroyed.

Stormed at by shot and shell, boldly we rode and well, flashed through the

valley of death, volleyed and thundered–straight into Lily Briscoe and

William Bankes. He quivered; he shivered.

Not for the world would she have spoken to him, realising, from the

familiar signs, his eyes averted, and some curious gathering together

of his person, as if he wrapped himself about and needed privacy into

which to regain his equilibrium, that he was outraged and anguished. She

stroked James’s head; she transferred to him what she felt for her

husband, and, as she watched him chalk yellow the white dress shirt of a

gentleman in the Army and Navy Stores catalogue, thought what a delight it

would be to her should he turn out a great artist; and why should he not?

He had a splendid forehead. Then, looking up, as her husband passed her

once more, she was relieved to find that the ruin was veiled; domesticity

triumphed; custom crooned its soothing rhythm, so that when stopping

deliberately, as his turn came round again, at the window he bent

quizzically and whimsically to tickle James’s bare calf with a sprig of

something, she twitted him for having dispatched “that poor young man,”

Charles Tansley. Tansley had had to go in and write his dissertation,

he said.

“James will have to write his dissertation one of these days,” he added

ironically, flicking his sprig.

Hating his father, James brushed away the tickling spray with which in a

manner peculiar to him, compound of severity and humour, he teased his

youngest son’s bare leg.

She was trying to get these tiresome stockings finished to send to

Sorley’s little boy tomorrow, said Mrs. Ramsay.

There wasn’t the slightest possible chance that they could go to the

Lighthouse tomorrow, Mr. Ramsay snapped out irascibly.

How did he know? she asked. The wind often changed.

The extraordinary irrationality of her remark, the folly of women’s minds

enraged him. He had ridden through the valley of death, been shattered

and shivered; and now, she flew in the face of facts, made his children

hope what was utterly out of the question, in effect, told lies. He

stamped his foot on the stone step. “Damn you,” he said. But what had she

said? Simply that it might be fine tomorrow. So it might.

Not with the barometer falling and the wind due west.

To pursue truth with such astonishing lack of consideration for other

people’s feelings, to rend the thin veils of civilization so wantonly, so

brutally, was to her so horrible an outrage of human decency that, without

replying, dazed and blinded, she bent her head as if to let the pelt of

jagged hail, the drench of dirty water, bespatter her unrebuked. There

was nothing to be said.

He stood by her in silence. Very humbly, at length, he said that he would

step over and ask the Coastguards if she liked.

There was nobody whom she reverenced as she reverenced him.

She was quite ready to take his word for it, she said. Only then they

need not cut sandwiches–that was all. They came to her, naturally, since

she was a woman, all day long with this and that; one wanting this,

another that; the children were growing up; she often felt she was nothing

but a sponge sopped full of human emotions. Then he said, Damn you. He

said, It must rain. He said, It won’t rain; and instantly a Heaven of

security opened before her. There was nobody she reverenced more. She

was not good enough to tie his shoe strings, she felt.

Already ashamed of that petulance, of that gesticulation of the hands when

charging at the head of his troops, Mr. Ramsay rather sheepishly prodded

his son’s bare legs once more, and then, as if he had her leave for it,

with a movement which oddly reminded his wife of the great sea lion at the

Zoo tumbling backwards after swallowing his fish and walloping off so that

the water in the tank washes from side to side, he dived into the evening

air which, already thinner, was taking the substance from leaves and

hedges but, as if in return, restoring to roses and pinks a lustre which

they had not had by day.

“Some one had blundered,” he said again, striding off, up and down the

terrace.

But how extraordinarily his note had changed! It was like the cuckoo;

“in June he gets out of tune”; as if he were trying over, tentatively

seeking, some phrase for a new mood, and having only this at hand, used

it, cracked though it was. But it sounded ridiculous–“Some one had

blundered”–said like that, almost as a question, without any conviction,

melodiously. Mrs. Ramsay could not help smiling, and soon, sure enough,

walking up and down, he hummed it, dropped it, fell silent.

He was safe, he was restored to his privacy. He stopped to light his

pipe, looked once at his wife and son in the window, and as one raises

one’s eyes from a page in an express train and sees a farm, a tree, a

cluster of cottages as an illustration, a confirmation of something on the

printed page to which one returns, fortified, and satisfied, so without

his distinguishing either his son or his wife, the sight of them fortified

him and satisfied him and consecrated his effort to arrive at a perfectly

clear understanding of the problem which now engaged the energies of his

splendid mind.

It was a splendid mind. For if thought is like the keyboard of a piano,

divided into so many notes, or like the alphabet is ranged in twenty-six

letters all in order, then his splendid mind had no sort of difficulty

in running over those letters one by one, firmly and accurately, until

it had reached, say, the letter Q. He reached Q. Very few people in

the whole of England ever reach Q. Here, stopping for one moment

by the stone urn which held the geraniums, he saw, but now far, far

away, like children picking up shells, divinely innocent and occupied with

little trifles at their feet and somehow entirely defenceless against a

doom which he perceived, his wife and son, together, in the window. They

needed his protection; he gave it them. But after Q? What comes next?

After Q there are a number of letters the last of which is scarcely

visible to mortal eyes, but glimmers red in the distance. Z is only

reached once by one man in a generation. Still, if he could reach R it

would be something. Here at least was Q. He dug his heels in at Q. Q he

was sure of. Q he could demonstrate. If Q then is Q–R–. Here he

knocked his pipe out, with two or three resonant taps on the handle of the

urn, and proceeded. “Then R …” He braced himself. He clenched

himself.

Qualities that would have saved a ship’s company exposed on a broiling

sea with six biscuits and a flask of water–endurance and justice,

foresight, devotion, skill, came to his help. R is then–what is R?

A shutter, like the leathern eyelid of a lizard, flickered over the

intensity of his gaze and obscured the letter R. In that flash of

darkness he heard people saying–he was a failure–that R was beyond him.

He would never reach R. On to R, once more. R–

Qualities that in a desolate expedition across the icy solitudes of the

Polar region would have made him the leader, the guide, the counsellor,

whose temper, neither sanguine nor despondent, surveys with equanimity

what is to be and faces it, came to his help again. R–

The lizard’s eye flickered once more. The veins on his forehead bulged.

The geranium in the urn became startlingly visible and, displayed among

its leaves, he could see, without wishing it, that old, that obvious

distinction between the two classes of men; on the one hand the steady

goers of superhuman strength who, plodding and persevering, repeat the

whole alphabet in order, twenty-six letters in all, from start to finish;

on the other the gifted, the inspired who, miraculously, lump all the

letters together in one flash–the way of genius. He had not genius; he

laid no claim to that: but he had, or might have had, the power to repeat

every letter of the alphabet from A to Z accurately in order. Meanwhile,

he stuck at Q. On, then, on to R.

Feelings that would not have disgraced a leader who, now that the snow has

begun to fall and the mountain top is covered in mist, knows that he must

lay himself down and die before morning comes, stole upon him, paling the

colour of his eyes, giving him, even in the two minutes of his turn on

the terrace, the bleached look of withered old age. Yet he would not die

lying down; he would find some crag of rock, and there, his eyes fixed

on the storm, trying to the end to pierce the darkness, he would die

standing. He would never reach R.

He stood stock-still, by the urn, with the geranium flowing over it. How

many men in a thousand million, he asked himself, reach Z after all?

Surely the leader of a forlorn hope may ask himself that, and answer,

without treachery to the expedition behind him, “One perhaps.” One in a

generation. Is he to be blamed then if he is not that one? provided he

has toiled honestly, given to the best of his power, and till he has no

more left to give? And his fame lasts how long? It is permissible even

for a dying hero to think before he dies how men will speak of him

hereafter. His fame lasts perhaps two thousand years. And what are two

thousand years? (asked Mr. Ramsay ironically, staring at the hedge).

What, indeed, if you look from a mountain top down the long wastes of the

ages? The very stone one kicks with one’s boot will outlast Shakespeare.

His own little light would shine, not very brightly, for a year or two,

and would then be merged in some bigger light, and that in a bigger still.

(He looked into the hedge, into the intricacy of the twigs.) Who then

could blame the leader of that forlorn party which after all has climbed

high enough to see the waste of the years and the perishing of the stars,

if before death stiffens his limbs beyond the power of movement he does a

little consciously raise his numbed fingers to his brow, and square his

shoulders, so that when the search party comes they will find him dead at

his post, the fine figure of a soldier? Mr. Ramsay squared his shoulders

and stood very upright by the urn.

Who shall blame him, if, so standing for a moment he dwells upon fame,

upon search parties, upon cairns raised by grateful followers over his

bones? Finally, who shall blame the leader of the doomed expedition, if,

having adventured to the uttermost, and used his strength wholly to the

last ounce and fallen asleep not much caring if he wakes or not, he now

perceives by some pricking in his toes that he lives, and does not on the

whole object to live, but requires sympathy, and whisky, and some one to

tell the story of his suffering to at once? Who shall blame him? Who

will not secretly rejoice when the hero puts his armour off, and halts by

the window and gazes at his wife and son, who, very distant at first,

gradually come closer and closer, till lips and book and head are clearly

before him, though still lovely and unfamiliar from the intensity of his

isolation and the waste of ages and the perishing of the stars, and

finally putting his pipe in his pocket and bending his magnificent head

before her–who will blame him if he does homage to the beauty of the

world?

7

But his son hated him. He hated him for coming up to them, for stopping

and looking down on them; he hated him for interrupting them; he hated him

for the exaltation and sublimity of his gestures; for the magnificence of

his head; for his exactingness and egotism (for there he stood, commanding

them to attend to him) but most of all he hated the twang and twitter of

his father’s emotion which, vibrating round them, disturbed the perfect

simplicity and good sense of his relations with his mother. By looking

fixedly at the page, he hoped to make him move on; by pointing his finger

at a word, he hoped to recall his mother’s attention, which, he knew

angrily, wavered instantly his father stopped. But, no. Nothing would

make Mr. Ramsay move on. There he stood, demanding sympathy.

Mrs. Ramsay, who had been sitting loosely, folding her son in her arm,

braced herself, and, half turning, seemed to raise herself with an effort,

and at once to pour erect into the air a rain of energy, a column of

spray, looking at the same time animated and alive as if all her energies

were being fused into force, burning and illuminating (quietly though she

sat, taking up her stocking again), and into this delicious fecundity,

this fountain and spray of life, the fatal sterility of the male plunged

itself, like a beak of brass, barren and bare. He wanted sympathy. He

was a failure, he said. Mrs. Ramsay flashed her needles. Mr. Ramsay

repeated, never taking his eyes from her face, that he was a failure.

She blew the words back at him. “Charles Tansley…” she said. But he

must have more than that. It was sympathy he wanted, to be assured of his

genius, first of all, and then to be taken within the circle of life,

warmed and soothed, to have his senses restored to him, his barrenness

made futile, and all the rooms of the house made full of life–the

drawing-room; behind the drawing-room the kitchen; above the kitchen the

bedrooms; and beyond them the nurseries; they must be furnished, they must

be filled with life.

Charles Tansley thought him the greatest metaphysician of the time, she

said. But he must have more than that. He must have sympathy. He must

be assured that he too lived in the heart of life; was needed; not only

here, but all over the world. Flashing her needles, confident, upright,

she created drawing-room and kitchen, set them all aglow; bade him take

his ease there, go in and out, enjoy himself. She laughed, she knitted.

Standing between her knees, very stiff, James felt all her strength

flaring up to be drunk and quenched by the beak of brass, the arid

scimitar of the male, which smote mercilessly, again and again,

demanding sympathy.

He was a failure, he repeated. Well, look then, feel then. Flashing her

needles, glancing round about her, out of the window, into the room, at

James himself, she assured him, beyond a shadow of a doubt, by her laugh,

her poise, her competence (as a nurse carrying a light across a dark room

assures a fractious child), that it was real; the house was full; the

garden blowing. If he put implicit faith in her, nothing should hurt him;

however deep he buried himself or climbed high, not for a second should he

find himself without her. So boasting of her capacity to surround and

protect, there was scarcely a shell of herself left for her to know

herself by; all was so lavished and spent; and James, as he stood stiff

between her knees, felt her rise in a rosy-flowered fruit tree laid with

leaves and dancing boughs into which the beak of brass, the arid scimitar

of his father, the egotistical man, plunged and smote, demanding sympathy.

Filled with her words, like a child who drops off satisfied, he said, at

last, looking at her with humble gratitude, restored, renewed, that he

would take a turn; he would watch the children playing cricket. He went.

Immediately, Mrs. Ramsey seemed to fold herself together, one petal closed

in another, and the whole fabric fell in exhaustion upon itself, so that

she had only strength enough to move her finger, in exquisite abandonment

to exhaustion, across the page of Grimm’s fairy story, while there

throbbed through her, like a pulse in a spring which has expanded to its

full width and now gently ceases to beat, the rapture of successful

creation.

Every throb of this pulse seemed, as he walked away, to enclose her and

her husband, and to give to each that solace which two different notes,

one high, one low, struck together, seem to give each other as they

combine. Yet as the resonance died, and she turned to the Fairy Tale

again, Mrs. Ramsey felt not only exhausted in body (afterwards, not at the

time, she always felt this) but also there tinged her physical fatigue

some faintly disagreeable sensation with another origin. Not that, as

she read aloud the story of the Fisherman’s Wife, she knew precisely what

it came from; nor did she let herself put into words her dissatisfaction

when she realized, at the turn of the page when she stopped and heard

dully, ominously, a wave fall, how it came from this: she did not like,

even for a second, to feel finer than her husband; and further, could not

bear not being entirely sure, when she spoke to him, of the truth of what

she said. Universities and people wanting him, lectures and books and

their being of the highest importance–all that she did not doubt for a

moment; but it was their relation, and his coming to her like that,

openly, so that any one could see, that discomposed her; for then people

said he depended on her, when they must know that of the two he was

infinitely the more important, and what she gave the world, in comparison

with what he gave, negligible. But then again, it was the other thing

too–not being able to tell him the truth, being afraid, for instance,

about the greenhouse roof and the expense it would be, fifty pounds

perhaps to mend it; and then about his books, to be afraid that he might

guess, what she a little suspected, that his last book was not quite his

best book (she gathered that from William Bankes); and then to hide small

daily things, and the children seeing it, and the burden it laid on

them–all this diminished the entire joy, the pure joy, of the two notes

sounding together, and let the sound die on her ear now with a dismal

flatness.

A shadow was on the page; she looked up. It was Augustus Carmichael

shuffling past, precisely now, at the very moment when it was painful to

be reminded of the inadequacy of human relationships, that the most

perfect was flawed, and could not bear the examination which, loving her

husband, with her instinct for truth, she turned upon it; when it was

painful to feel herself convicted of unworthiness, and impeded in her

proper function by these lies, these exaggerations,–it was at this

moment when she was fretted thus ignobly in the wake of her exaltation,

that Mr. Carmichael shuffled past, in his yellow slippers, and some demon

in her made it necessary for her to call out, as he passed,

“Going indoors Mr. Carmichael?”

8

He said nothing. He took opium. The children said he had stained his

beard yellow with it. Perhaps. What was obvious to her was that the poor

man was unhappy, came to them every year as an escape; and yet every year

she felt the same thing; he did not trust her. She said, “I am going to

the town. Shall I get you stamps, paper, tobacco?” and she felt him

wince. He did not trust her. It was his wife’s doing. She remembered

that iniquity of his wife’s towards him, which had made her turn to steel

and adamant there, in the horrible little room in St John’s Wood, when

with her own eyes she had seen that odious woman turn him out of the

house. He was unkempt; he dropped things on his coat; he had the

tiresomeness of an old man with nothing in the world to do; and she turned

him out of the room. She said, in her odious way, “Now, Mrs. Ramsay and I

want to have a little talk together,” and Mrs. Ramsay could see, as if

before her eyes, the innumerable miseries of his life. Had he money

enough to buy tobacco? Did he have to ask her for it? half a crown?

eighteenpence? Oh, she could not bear to think of the little indignities

she made him suffer. And always now (why, she could not guess, except

that it came probably from that woman somehow) he shrank from her. He

never told her anything. But what more could she have done? There was a

sunny room given up to him. The children were good to him. Never did she

show a sign of not wanting him. She went out of her way indeed to be

friendly. Do you want stamps, do you want tobacco? Here’s a book you

might like and so on. And after all–after all (here insensibly she drew

herself together, physically, the sense of her own beauty becoming, as it

did so seldom, present to her) after all, she had not generally any

difficulty in making people like her; for instance, George Manning; Mr.

Wallace; famous as they were, they would come to her of an evening,

quietly, and talk alone over her fire. She bore about with her, she could

not help knowing it, the torch of her beauty; she carried it erect into

any room that she entered; and after all, veil it as she might, and shrink

from the monotony of bearing that it imposed on her, her beauty was

apparent. She had been admired. She had been loved. She had entered

rooms where mourners sat. Tears had flown in her presence. Men, and

women too, letting go to the multiplicity of things, had allowed

themselves with her the relief of simplicity. It injured her that he

should shrink. It hurt her. And yet not cleanly, not rightly. That was

what she minded, coming as it did on top of her discontent with her

husband; the sense she had now when Mr. Carmichael shuffled past, just

nodding to her question, with a book beneath his arm, in his yellow

slippers, that she was suspected; and that all this desire of hers to

give, to help, was vanity. For her own self-satisfaction was it that she

wished so instinctively to help, to give, that people might say of her,

“O Mrs. Ramsay! dear Mrs. Ramsay … Mrs. Ramsay, of course!” and need her

and send for her and admire her? Was it not secretly this that she

wanted, and therefore when Mr. Carmichael shrank away from her, as he did

at this moment, making off to some corner where he did acrostics

endlessly, she did not feel merely snubbed back in her instinct, but made

aware of the pettiness of some part of her, and of human relations, how

flawed they are, how despicable, how self-seeking, at their best. Shabby

and worn out, and not presumably (her cheeks were hollow, her hair was

white) any longer a sight that filled the eyes with joy, she had better

devote her mind to the story of the Fisherman and his Wife and so pacify